-

1 Form of Digital Justice Technologies

Before embarking on an analysis of technological change and the courts’ response, it is necessary to begin with matters of definition. A major part of the challenge in anticipating how digital technologies may impact upon the efficiency and functioning of courts is to clearly define the ambit of the enquiry. This is complicated because digital justice lacks a shared common language and conceptual taxonomy. We begin, therefore, with a taxonomy to help frame the topic and foster clearer communication about the issues, scope and benefits of potential reforms.

1.1 Taxonomy of Justice Technology, Online Dispute Resolution and Online Courts

The issue of terminology is particularly acute in the emerging areas of Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) and Online Courts. Not only are various names – including Electronic Dispute Resolution, ODR, Internet Dispute Resolution, Online ADR15x See V. Tan, ‘Online Dispute Resolution for Small Civil Claims in Victoria: A New Paradigm in Civil Justice,’ Deakin Law Review, Vol. 24, 2019, pp. 101, 103-104; M. Legg, ‘The Future of Dispute Resolution: Online ADR and Online Courts’, Australasian Dispute Resolution Journal, Vol. 27, 2016, p. 277. and ‘Online Courts’16x See D. Menashe, ‘A Critical Analysis of the Online Court’, University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law, Vol. 39, No. 4, 2018, p. 921; A. Sela, ‘Streamlining Justice: How Online Courts Can Resolve the Challenges of Pro Se Litigation’, Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy, Vol. 26, No. 2, 2018, p. 331; Legg, supra n. 15, p. 277. – used interchangeably to describe the relevant systems, the minimum required to constitute such a system is itself contested. For some authors, ODR is given a broad inclusive definition. Sourdin and Liyanage, for example, use the term ODR to “refer to dispute resolution processes conducted with the assistance of communications and information technology, particularly the internet”.17x T. Sourdin & C. Liyanage, The Promise and Reality of Online Dispute Resolution in Australia, in M. S. Abdel Wahab, E. Katsh & D. Rainey (Eds.), Online Dispute Resolution: Theory and Practice, Eleven International Publishing, The Hague, 2012, pp. 483, 484 (emphasis added). For many though, this threshold of ‘assistance’ is too low. Richard Susskind, for example, argues that the central idea of ODR is that “the process of resolving a dispute, especially the formulation of the solution, is entirely or largely conducted through the internet”.18x R. Susskind, Tomorrow’s Lawyers: An Introduction to Your Future, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2017, p. 111 (emphasis added). Similarly, Palmgren argues that ODR means that “the dispute resolution process, be it litigation, arbitration, mediation, facilitation or negotiation, is conducted entirely or largely online without the need to attend a physical court or hearing facility”.19x K. Palmgren, Churchill Fellowship Report 2018: Explore the Use of Online Dispute Resolution to Resolve Civil Disputes (Report, Winston Churchill Memorial Trust, November 2018), p. 15 (emphasis added). In this vein, Tan argues that a

true ODR system should be defined as a system that allows parties to resolve their disputes from beginning to end, that is from the making of the claim to the resolution of the dispute, in an online forum.20x Tan, supra n. 15, p. 104.

These different approaches show that there is often a lack of shared understanding of the scope, purpose or limits of digitization of court processes. The first step in understanding the use of digital justice technologies to enhance court efficiencies is to define what is meant by the ‘processes of the court’: to increase ‘court capacity’ begs the question, ‘capacity to do what’?

1.2 The Capacity of Courts to Resolve Disputes

The role of courts to resolve disputes on the basis of their legal merits is commonly seen as the most obvious aspect of the judicial function.21x J. McIntyre, The Judicial Function: Fundamental Principles of Contemporary Judging, Springer, Singapore, 2019, Pt II. It is important to bear in mind, however, that the act of judicial resolution sits at the end of a chain of processes commonly involving other forms of dispute resolution. A typical civil dispute will progress through a number of phases (often cycling back through various phases) before it is finally resolved. Such a dispute will commonly follow this progression:

Information Gathering → Obtaining Advice → Direct Negotiation → Supported Negotiation → Adjudication.

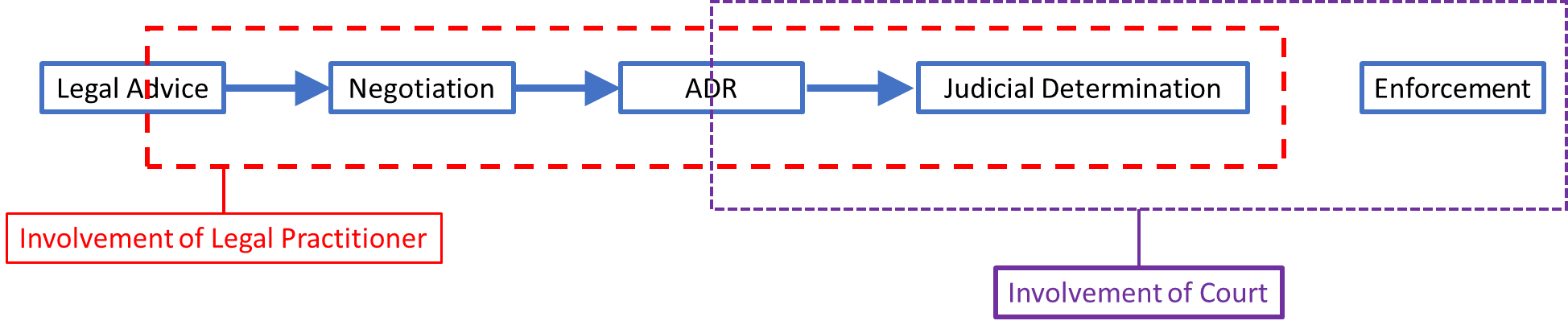

In traditional litigation, the role of the court is restricted and generally arises in the final phases of the resolution progression (Figure 1):

Traditional Legal Resolution of Disputes

If the intention is to increase court capacity only in that final stage of judicial determination, then the range of technologies and options need to focus purely on that phase. However, if the focus on ‘court capacity’ is conceived more broadly, to incorporate the enhanced performance of the systems of public civil dispute resolution systems, then a greater potential for the use of technologies arise.

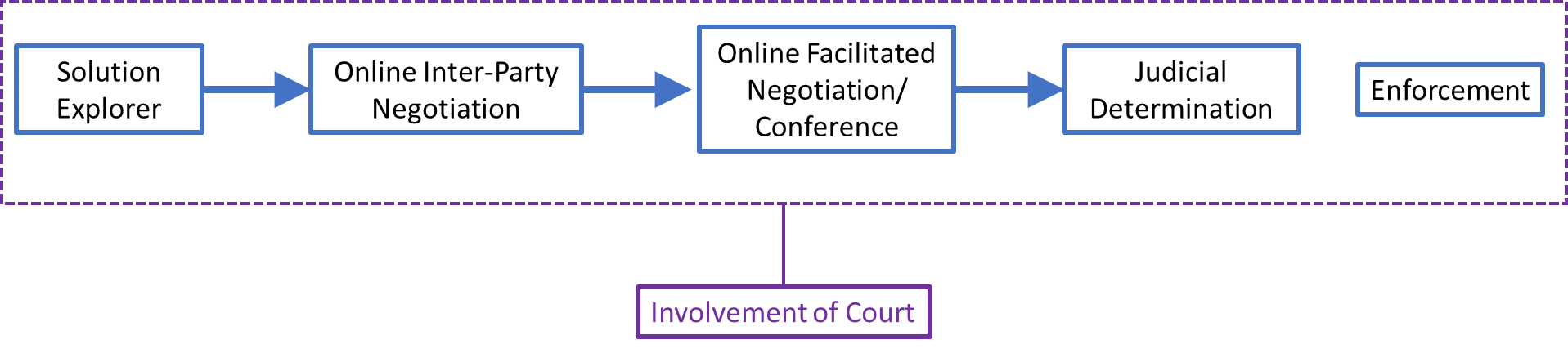

In the growing literature and practice of ‘integrated online court systems’, the role of the court is conceived more broadly. The court, in this context, may be involved in a range of the various dispute resolution activities and potentially in all five phases (Figure 2).Integrated Online Court Resolution of Disputes

This broader sweep of involvement creates significant advantages in terms of potentially increasing access to justice,22x See E. Katsh & O. Rabinovich-Einy, Digital Justice: Technology and the Internet of Disputes, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2017, pp. 170-184; Tan, supra n. 15, pp. 129-132. increasing speed and efficiency of processes, reducing duplications and redundancies and promoting the effective deployment of judicial resources. However, such a ‘full-suite’ service represents a dramatic expansion of the role of the court, greatly beyond even that assumed in vigorous judicial case management. This expansion has also raised concerns where it involves imposing additional hurdles (and costs) for a person who needs to access judicial determination and/or enforcement.23x M. Legg & D. Boniface, ‘Pre-action Protocols in Australia’, Journal of Judicial Administration, Vol. 20, 2010, pp. 39, 50; Lord Justice Briggs, Civil Courts Structure Review – Final Report (July 2016), paras. [6.108]-[6.109].

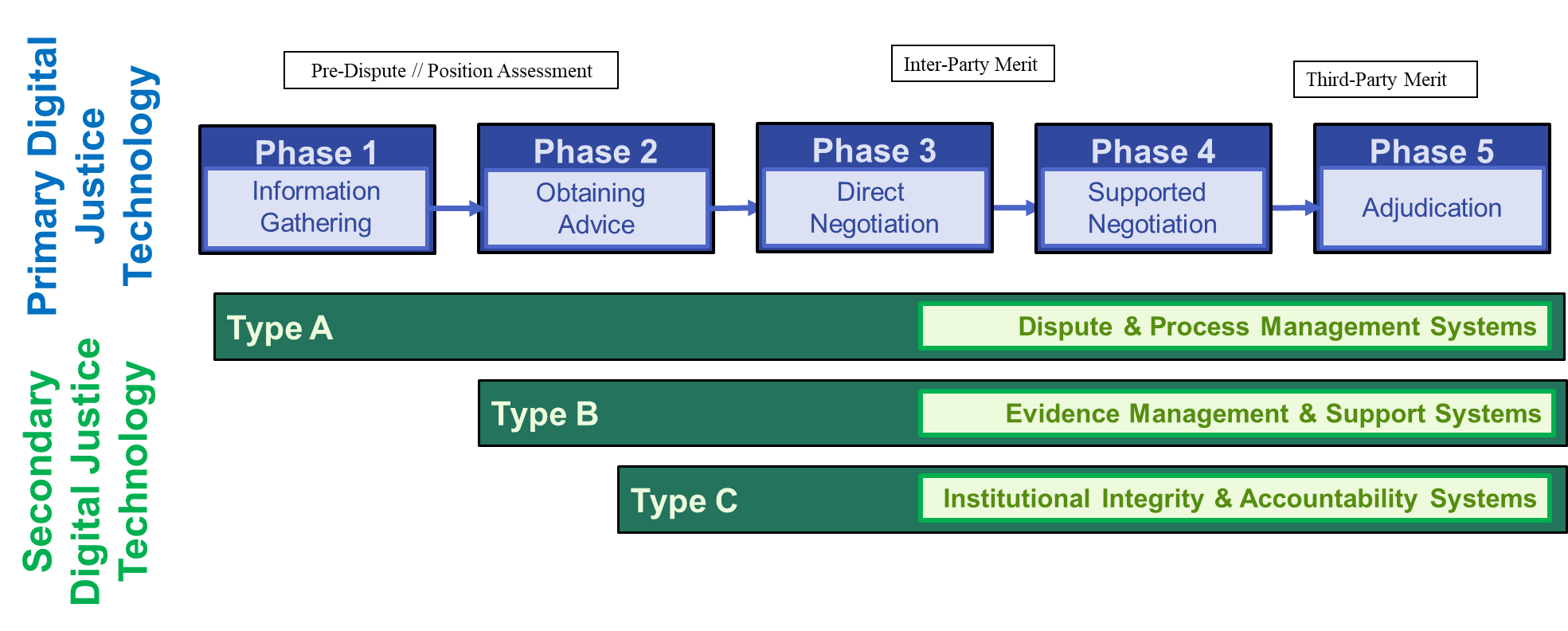

Moreover, each of these phases offer potential opportunities for automation, and different sites in which artificial intelligence could potentially be deployed to increase capacity. Digital justice technologies can be deployed in each of these phases, and there are already products on the market that demonstrate those possibilities.24x For an overview of such systems, see, generally Bennett et al., ‘Current State of Automated Legal Advice Tools’, Networked Society Institute Discussion Paper, 1 April 2018; M. Legg & F. Bell, Artificial Intelligence and the Legal Profession, Hart, Oxford, 2020, Chs. 4, 5 and 6.

Digital justice technologies have a secondary role as well, supporting and enabling the performance of the primary roles identified in the phases above; these roles can include lodgement and case management, evidence management and institutional integrity and accountability systems (Figure 3).Taxonomy of Digital Justice Technologies

This taxonomy helps to lay out the distinct roles that are performed in the delivery of online justice. To a large extent, these roles replicate the roles that are performed in the traditional judicial resolution of disputes. The difference here, however, is that the court may be involved, in one form or another, from the very first phase.

Dispute Phase Technology Function/Role Information gathering Technology helps the parties gather general information about their legal rights and responsibilities and how these may be enforced. This information is largely generic and of general application. Obtaining advice Technology helps provide the parties with legal advice that is tailored to their specific situation and provides some guidance as to how they could or should proceed. Direct negotiation Technology helps the parties directly negotiate with each other in an attempt to reach a mutually tolerable settlement of the dispute. Supported negotiation Technology helps support the parties in their negotiation by a third party, who helps the parties reach a mutually tolerable settlement of the dispute through a range of techniques, including framing, interest identification and articulation of ends. Adjudication Technology helps the parties and the third party (who has assumed control of the determination of the dispute, and delivers a final, binding and authoritative judgement that concludes the dispute) in advancing the adjudication. These primary functional roles are augmented by a range of secondary roles that support the parties in presenting, and progressing, their dispute.

Support Technology Function/Role Dispute and process management Technology helps the parties initiate their dispute resolution process, provide relevant information, lodge key documents and manage the logistics. Evidence management and support systems Technology helps the parties lodge, manage, access and share evidence relevant to the dispute. Institutional integrity and accountability systems Technology helps ensure the integrity and accountability of the dispute resolution as a whole, gathering and analysing data about the performance of various aspects within the system and sharing information with parties, administrators and judicial officers. Taken together, we see the full suite of possible activities in delivering online justice where potential technologies can be deployed – both for primary dispute resolution purposes and secondary-support services.

The point we wish to illustrate is that the capacity of courts to deliver justice can be enhanced through a broad range of technologies, some of which will be directed to ‘primary’ roles of actually resolving disputes and some of which will perform ‘secondary’ support roles to enhance institutional capacity and performance.1.3 The Capacity of Courts to Contribute to Social Governance

Of course, the role of courts is substantially broader than that of mere dispute resolution. Courts are performing a key public role of social governance: maintaining social order and a system of legality, together with clarifying, interpreting and developing legal norms.25x McIntyre, supra n. 21, pp. 56-66. See also M. Legg & S. Mirzabegian, ‘Appropriate Dispute Resolution and the Role of Litigation’, Australian Bar Review, Vol. 38, 2013, pp. 55, 57-63.

There are few better statements of this public governance role of court – and of the constitutional significance of ensuring access to those courts – than the decision of the UK Supreme Court in UNISON.26x R (on the application of UNISON) v. Lord Chancellor [2017] UKSC 51 (26 July 2017). UNISON was a case in which the Supreme Court considered the validity of fees imposed by the Lord Chancellor on persons wishing to access employment tribunals. In that case, Lord Reed articulated the following key principles concerning the right of access to the courts:At the heart of the concept of the rule of law is the idea that society is governed by law. … Courts exist in order to ensure that the laws made by Parliament, and the common law created by the courts themselves, are applied and enforced. … In order for the courts to perform that role, people must in principle have unimpeded access to them. Without such access, laws are liable to become a dead letter…. That is why the courts do not merely provide a public service like any other.27x Id. [68].

…[T]he value to society of the right of access to the courts is not confined to cases in which the courts decide questions of general importance. People and businesses need to know, on the one hand, that they will be able to enforce their rights if they have to do so, and, on the other hand, that if they fail to meet their obligations, there is likely to be a remedy against them. It is that knowledge which underpins everyday economic and social relations. That is so, notwithstanding that judicial enforcement of the law is not usually necessary, and notwithstanding that the resolution of disputes by other methods is often desirable.28x Id. [71].

In the Australian context, former Chief Justice of the High Court Sir Gerard Brennan made a similar point:

The settlement of disputes by legal process is a fundamental function of government in a society under the rule of law. If the function is not performed, the law is not applied and the festering sore of injustice spreads the infection of self-help. Power is then unrestrained by law. Peace and order are at risk and, sometimes, tragedy may be the consequence. Laws that are put on the statute book mock the integrity of the political process unless the beneficiaries of those laws can enforce them.29x Sir G. Brennan, ‘Key Issues in Judicial Administration’, Journal of Judicial Administration, Vol. 6, 1996, pp. 138, 140.

These principles are critical to bear in mind in designing technological solutions to issues of court capacity. The conduct of judicial proceedings in a publicly open and visible manner is not only about principles of ‘open justice’ in a judicial accountability sense. Rather, such openness is vital to fulfilling this public governance function of courts – developing and clarifying norms yes, but also demonstrably reinforcing their vitality.30x McIntyre, supra n. 21, p. 59.

Such ‘constitutional’ principles were (properly) irrelevant to the design – historically – of private ODR systems.31x Legg, ‘The Future of Dispute Resolution’, supra n. 15, p. 235. For a history of the development of private ODR systems, see Katsh & Rabinovich-Einy, supra n. 22, Ch. 11. However, in developing modern integrated Online Courts, it is vital to ensure that such systems operate to ensure an adequate degree of visibility and ‘presence’. There is a risk that transition to digital systems may act to minimize these public aspects of the role, furthering a misapprehension that courts are performing a ‘private service’ of dispute resolution. Over time, such an approach may serve to undermine court capacity, as without the public clarification of norms and the reaffirmation of legal principles, parties may become more dependent upon judges to resolve the dispute through the delivery of individual judicial determinations.

However, well-designed Online Court systems are capable of enhancing this public governance role. Judgements can, for example, be delivered in ways that lead to better integration with automated information and advice systems. This may include through the use of structured data input and analysis, the linking of relevant judgements to automated negotiation processes and the improved information for provision of early legal information and advice. Similarly, institutional accountability and performance systems can operate to give parties much greater guidance as to real-time expectation of how long proceedings will take – thereby allowing parties to make more informed settlement decisions.

There has been, to date, very little analysis of the opportunities of technological solutions to enhance the public governance capacity of courts. However, this issue should not be ignored. If the systemic capacity of courts is to be meaningfully and sustainably enhanced, these factors require much greater substantiated analysis. -

2 Use of Technology to Increase Court Efficiency in Australia

Contrary to public perception, technology has long had a significant role within Australian courts.32x L. Bennett Moses, ‘Artificial Intelligence in the Courts, Legal Academia and Legal Practice’, Australian Law Journal, Vol. 91, No. 7, 2017, p. 561. Supportive technology is used as a matter of routine33x Chief Justice T. Bathurst, Supreme Court of New South Wales, ‘ADR, ODR and AI-DR, or Do We Even Need Courts Anymore?’ (Inaugural Supreme Court ADR Address, 20 September 2018), p. 4. and includes AVLs, e-filing, e-discovery, real-time transcription services and the use of devices on the bench and at the bar table.34x Justice M. Beazley, ‘Law in the Age of the Algorithm’ (State of the Profession Address, Sydney, 21 September 2017), pp. 9-10. AVL technology, in particular, has been in use for decades,35x Victorian Parliamentary Law Reform Committee, Technology and the Law, Report (May 1999), para. [10.33]; A. Wallace, S. Roach Anleu & K. Mack, ‘Judicial Engagement and AV Links: Judicial Perceptions from Australian Courts’, International Journal of the Legal Profession, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2019, pp. 51, 53. reaching ubiquity in some aspects of the operation of all Australian courts by 2004.36x A. Wallace & R. Macdonald, ‘Review of the Extent of Courtroom Technology in Australia’, William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2004, pp. 649, 651.

However, the uptake of technology to enhance court efficiency has been notably uneven across jurisdictions, and even within jurisdictions. For example, while the Federal Court has generally excellent technological capability, the Family Court was comparably under-resourced and some States have been particularly slow. Even in tech-forward jurisdictions, the use of technology has often been constrained: despite technological capacity, AVL has – for example – largely been used for interlocutory matters or individual witnesses in discrete circumstances rather than full trials.

Resistance to change in parts of the legal profession, plus lack of resources, have slowed down adoption of technology. For example, in the Federal Circuit and Family Court,37x Formerly the Family Court of Australia and the Federal Circuit Court of Australia. AVL has theoretically been available as a means of protecting vulnerable parties by ensuring their physical separation from an alleged perpetrator. This technology was reportedly under-utilized prior to the pandemic.38x See Parliament of Australia, Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Inquiry into the Family Law Amendment (Family Violence and Cross-examination of Parties) Act 2018 (Report, 13 August 2018).2.1 Use of Secondary ‘Support’ Technologies

As noted, digital justice technologies offer a broad suite of solutions that can contribute to court capacity. A focus only on the use of AVL and online hearings not only misses these opportunities but can also become unduly distracted by potential challenges and issues (particularly where potential technological solutions may exist).

Perhaps the most significant uptake of digital justice technology in Australia has been in the context of secondary ‘support’ technologies – electronic filing, case management, document management and so on. Greater willingness to adopt technology for ‘back room’ functions rather than more prominent litigant-facing functions is probably related to logistical and administrative advantages these technologies bring, and their relative distance from the core business of judicial proceedings and decision-making.

Courts have been introducing these forms of technology into various parts of their processes for a considerable time.39x See generally Australian Law Reform Commission, Technology–What it Means for Federal Dispute Resolution, Issues Paper No. 23 (1998); A. Wallace, ‘The Challenge of Information Technology in Australian Courts’, Journal of Judicial Administration, Vol. 9, No. 1, 1999, p. 8; Wallace & Macdonald, supra n. 36. For example, in relation to document management and communication, NSW started in the late 1990s to create CourtLink,40x Justice G. Lindsay, The Civil Procedure Regime in New South Wales – A View from 2005, in M. Kumar and M. Legg (Eds.), Ten Years of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW), Thomson Reuters, Sydney, 2015, p. 30. later renamed JusticeLink, to facilitate case management, document transfer and the exchange of data with other government agencies such as Corrective Services.41x L. Tay, ‘NSW Sees Value in Slow, Costly IT Projects’, itnews, 2 December 2010 (reporting that JusticeLink was completed in June 2010). The Federal Court has also moved to an Electronic Court File and adopted an ‘eLodgment’ system, and the Victorian Supreme Court has an electronic filing and case management system called RedCrest.42x Chief Justice J. Allsop, ‘Technology and the Future of the Courts’, University of Queensland Law Journal, Vol. 38, No. 1, 2019, pp. 1, 4.

Unfortunately, emergency systems of online hearings that have been used during the COVID-19 pandemic have not fully embraced these secondary justice technology systems. This is not surprising given that courts have largely relied upon generic video-conferencing systems that are not yet integrated into these secondary systems (even where these digital systems exist). However, as courts begin to shift to longer term planning, it is important that the opportunities presented by these related support technologies be taken up.2.2 Use of AVLs and Online Hearings in Australia

Australian courts have also used technology in relation to hearings. The use of video conferencing can be traced back to at least 199743x Sunstate Airlines (Qld) Pty Ltd v. First Chicago Australia Securities Ltd (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Giles CJ, 11 March 1997), p. 6. See also A. Wallace, ‘“Virtual Justice in the Bush”: The Use of Court Technology in Remote and Regional Australia’, Journal of Law, Information and Science, Vol. 19, 2008, p. 1. and is now used extensively in Australian courts, although usually (as noted) referred to as AVL.44x R. Lulham et al., ‘Court-Custody Audio Visual Links: Designing for Equitable Justice Experience in the Use of Court Custody Video Conferencing’ (Research Report, Designing Out Crime, University of Technology Sydney, 1 September 2017), p. 9; Wallace, Roach Anleu & Mack, supra n. 35, p. 53. The Federal Court’s website reports that on 3 August 1999 it became the first Australian court to broadcast live streaming video and audio of a judgement summary over the Internet.45x Federal Court of Australia, Videos (Web Page), www.fedcourt.gov.au/digital-law-library/videos. The case was Australian Olympic Committee Inc v. Big Fights Inc [1999] FCA 1042. See also Supreme Court of Victoria, Webcasts and Podcasts (Web Page), www.supremecourt.vic.gov.au/about-the-court/webcasts-and-podcasts. NSW created an Online Court that allowed for a virtual hearing using email or instant messaging in particular Supreme, District or Local Court matters.46x New South Wales’ Justice Courts & Tribunal Services, Online Court User Guide, Version 1.3, 23 January 2019. See also Supreme Court of NSW, Practice Note No. SC Gen 12, Online court Protocol, 8 February 2007 (applying to matters in the Court of Criminal Appeal where either an Application for Extension of Time or a Notice of Appeal has been lodged, matters in the Common Law Division and selected matters in the Equity Division, but does not apply to proceedings involving self-represented litigants). The Online Court’s first hearing was in 2006.47x M. Pelly, ‘Internet Court Gets First Case’, Sydney Morning Herald, 1 April 2006. Technology has also been used to facilitate discovery and at trial to manage and show exhibits to the judge, lawyers, witnesses and the public.48x See, e.g. Justice D. Hammerschlag, Hammerschlag’s Commercial Court Handbook, LexisNexis, Australia, 2019, pp. 8-9. Trials have tended to operate in a format similar to that which has been in place for hundreds of years, with most participants physically present in the courtroom. However, legislation authorizes the appearance by AVL for parties, witnesses and defendants,49x Wallace, Roach Anleu & Mack, supra n. 35. In NSW see: ss 61 and 62 Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW), s 5B of the Evidence (Audio and Audio Visual Links) Act 1998 (NSW) and r 31.3 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules. For Federal Courts, see: ss 47 to 47G Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and Sections 66 to 73 Federal Circuit Court of Australia Act 1999 (Cth). and is a matter for the primary judge’s discretion exercised in accordance with the circumstances of a particular case.50x ASIC v. Rich (2004) 49 ACSR 578; Kirby v. Centro Properties Limited (2012) 288 ALR 601. In criminal proceedings and in civil protective order proceedings involving vulnerable witnesses such as children or victims of family violence or sexual assault, AVL has for some time been available to prevent the witness from being physically present in the room with the alleged perpetrator.51x E.g., Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) s 15YI; Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW) s 306ZB. A complete summary of the legislation can be found in the National Domestic and Family Violence Bench Book (Australian Institute of Judicial Administration), https://dfvbenchbook.aija.org.au/, section 9.2.3. See also J. Cashmore & L. Trimboli, An Evaluation of the New South Wales Child Sexual Assault Specialist Jurisdiction Pilot, New South Wales Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Sydney, 2006; N. Taylor & J. Joudo Larsen, The Impact of Pre-recorded Video and Closed Circuit Television Testimony by Adult Sexual Assault Complainants on Jury Decision-making: An Experimental Study (Research and Public Policy Series No. 68, Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, 2005).

2.3 Use of ODR Technologies in Australia

By and large, however, this use of AVL technologies has not been translated into any broader embrace of other forms of ODR justice technologies. It is difficult to reach confident conclusions about the success of the use of technology during the pandemic. The pandemic has forced Australian courts and lawyers to rely on technology more than ever before. Yet there has been little systematic evaluation of the results.52x Exceptions include Grata Fund, Australian Courts: How a Global Pandemic Built our Launchpad into the Future (29 May 2020) and the Australian Centre for Justice Innovation (ACJI) at Monash University, Australia, and the University of Otago Legal Issues Centre, New Zealand, The Remote Justice Research Project (Web Page), www.remotejusticestories.org/research. Anecdotally, our general impression is that courts have operated effectively during the pandemic. Lawyers, judges and court staff have displayed skill, diligence and flexibility in adapting to the use of technology. As we explain below, there have been some concerns about the fairness and accessibility of justice during this time.

We are also hearing some doubt that the technological solutions adopted during the pandemic should have an ongoing place in the justice system, as opposed to being a short-term emergency solution. There may be a preference for contested arguments and trial to take place face-to-face, though we may expect to see more procedural hearings dealt with by AVL in future.

In contrast, the last decade has seen the emergence of ODR systems and techniques in public dispute resolution systems across the globe. Pre-COVID-19, jurisdictions including British Columbia in Canada,53x See Civil Resolution Tribunal (Web Page), https://civilresolutionbc.ca/; S. Salter, ‘Online Dispute Resolution and Justice System Integration: British Columbia’s Civil Resolution Tribunal,’ Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice, Vol. 34, No. 1, 2017, p. 112. Ireland,54x See C. Keena, ‘€100 Million Digital-First Plan for Courts Could Allow Online Guilty Pleas’, Irish Times, 18 January 2020. the Netherlands,55x While components were initially developed as early as 2007, the Dutch Legal Aid Board, together the Hague Institute for Innovation of Law and Modria, formally launched the much lauded ‘Rechtwijzer’ platform in 2015: HiiL, ‘Rechtwijzer Launches in the Netherlands’ (Web Page, 2015), www.hiil.org/news/rechtwijzer-launches-in-the-netherlands/. The system operated for just over two years before it was disbanded: see R. Smith, ‘The Decline and Fall (and Potential Resurgence) of the Rechtwijzer’, Legal Voice (Web Page, 2017), http://legalvoice.org.uk/decline-fall-potential-resurgence-rechtwijzer/; M. Barendrecht, ‘Rechtwijzer: Why Online Supported Dispute Resolution is Hard to Implement’, Law, Technology and Access to Justice (Web Page, 2017), https://law-tech-a2j.org/odr/rechtwijzer-why-online-supported-dispute-resolution-is-hard-to-implement/. China56x China has adopted digital technologies far more extensively than any other country, though this approach has raised many questions about legitimacy and independence: A. Xu, ‘Chinese Judicial Justice on the Cloud: A Future Call or a Pandora’s Box? An Analysis of the “Intelligent Court System” of China’, Information and Communications Technology Law, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2017, p. 59. and a number of US states57x See D. Himonas, ‘Utah’s Online Dispute Resolution Program’, Dickson Law Review, Vol. 122, No. 3, 2018, p. 87. had already begun to examine the opportunities presented by these modern systems.58x For a useful overview of some these developments see O. Rabinovich-Einy & E. Katsh, ‘The New New Courts,’ American University Law Review, Vol. 67, No. 1, 2017, pp. 165, 188-203; Legg & Bell, supra n. 24, Ch. 6.

Despite being early leaders in digital justice technology,59x For example, the Federal Court was one of the first national courts systems to embrace electronic submissions with the launch of ‘eCourtroom’ in February 2001. See K. Finlayson, T. Laing & T. Mills, ‘A Practical Guide to e-litigation: Part 2: e-litigation in the Federal Court,’ Proctor, Vol. 31, n. 3, 2011, p. 2. Similarly, the Australian Legal Information Institute (AustLII) launched by the University of New South Wales and the University of Technology Sydney in 1995 was one of the earliest of such bodies, launched within three years of the first LII at Cornell. Australia is relatively late to the party in the adoption of ODR systems, though with quick uptake of ‘remote’ technologies in response to COVID-19.60x F. Bell, ‘“Part of the Future”: Family Law, Children’s Interests and Remote Proceedings in Australia During COVID-19’, University of Queensland Law Journal, Vol. 40, No. 1, 2021, p. 1. Several States are currently at the investigatory stage, examining the potential advantages and costs of adopting such a system. For example, the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal undertook an ODR pilot in September 201861x Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal, ‘Sharing VCAT’s Online Dispute Resolution Experience’, VCAT (Web Page, 21 November 2018), www.vcat.vic.gov.au/news/sharing-vcats-online-dispute-resolution-experience. to conduct video hearings and electronic file sharing.62x For reflections on this pilot, see Tan, supra n. 15, pp. 126-127. Similarly, in late 2014 the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal undertook a pilot to provide ODR for consumer disputes for claims under $5000.63x Justice R. Wright, Civil and Administrative Tribunal of NSW, Annual Report 2014-2015, 2015, p. 79.

Research was recently completed, in collaboration with the South Australian Civil and Administrative Tribunal and Consumer Business Services, to examine the viability of utilizing ODR techniques to resolve certain residential tenancy disputes.64x See J. McIntyre et al., Final Report: An Online Residential Tenancies Bond System for SA (29 September 2020), UniSA: Justice and Society, https://hdl.handle.net/11541.2/144706. This research project, to which two of the authors of this article contributed, was funded by the South Australian Law Foundation. This Report illustrated how the embrace of a fully integrated system – covering all phases of dispute resolution from information provision to final determination – can lead to significant savings for all parties, as well as increasing systemic efficiency and the protection of rights.

However, we are yet to see the permanent adoption of an ODR system in any Australian jurisdiction. While we are seeing a rapid transition to the use of online hearings as part of the changes necessitated by COVID-19,65x See J. McIntyre, A. Olijnyk & K. Pender, ‘Civil Courts and COVID-19: Challenges and Opportunities in Australia’, Alternative Law Journal, Vol. 45, No. 3, 2020, p. 95; M. Legg & A. Song, ‘Commercial Litigation and COVID-19 – the Role and Limits of Technology’, Australian Business Law Review, Vol. 48, 2020, p. 159; M. Legg, ‘The COVID-19 Pandemic, the Courts and Online Hearings: Maintaining Open Justice, Procedural Fairness and Impartiality’, Federal Law Review, Vol. 49, 2021, p. 161. these changes have not yet developed into a full-blown adoption of ODR techniques. -

3 Challenges and Solutions

This section identifies challenges that have arisen around the use of technology in Australian courts and the solutions that have been adopted.

3.1 Open Justice and Online Hearings

The principle of open justice has been said to be

one of the most fundamental aspects of the system of justice in Australia. The conduct of proceedings in public … is an essential quality of an Australian court of justice[.]66x John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd v. District Court of New South Wales [2004] NSWCA 324. See also Dickason v. Dickason (1913) 17 CLR 50, 51 (‘one of the normal attributes of a Court is publicity, that is, the admission of the public to attend the proceedings’.); Hogan v. Hinch (2011) 243 CLR 506, p. 530, para. [20]. (‘An essential characteristic of courts is that they sit in public’.).

Pre-pandemic, open justice was achieved through a combination of mechanisms, many of which were taken for granted. Traditionally, open justice is derived from court rooms being open to the public, the availability of transcripts (typically at a price) and the provision of reasons (usually sometime after the hearing). The events witnessed or recorded in each of these activities may then be further disseminated by the media.

With the advent of the pandemic and the need to close or limit the capacity of physical court rooms, open justice was front of mind for most Australian courts who addressed it via public announcements and new operating procedures. In the Federal Court of Australia, a Special Measures Information Note (SMIN-1) identified the need ‘to facilitate open and accessible courts’.67x Federal Court of Australia, Special Measures in Response to COVID-19 (SMIN-1), 23 March 2020, [9.3]. See also, Australian Securities and Investments Commission v. GetSwift Limited [2020] FCA 504, para. [41]. The Federal Court adopted a range of approaches to achieving that goal. Some hearings were screened in a physical courtroom open to the public, but with social distancing (although, once stay-at-home orders were in place, members of the public could not physically attend the court). Access to hearings by telephone or Microsoft Teams could be obtained by interested members of the public contacting the court for dial-in details or links to join the hearing.68x Saunders on Behalf of the Bigambul People v. State of Queensland [2020] FCA 563, para. [62]; Quirk v. Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (Remote Video Conferencing) [2020] FCA 664. The Family Court adopted a similar procedure. For example one shareholder class action, settlement hearing offered each of these options.69x Fisher (trustee for the Tramik Super Fund Trust) v. Vocus Group Limited (No. 2) [2020] FCA 579, para. [12]. In another class action, the settlement approval hearing was conducted by videoconference using Microsoft Teams with parties and lawyers at 15 separate remote locations. To facilitate open justice, the judge sat in the physical courtroom that was open to the public, but set up consistent with physical distancing, with the video on display screens. A full transcript of the hearing was made by the Court’s official transcript service, and an additional back-up recording was made using the Microsoft Teams technology.70x Cantor v. Audi Australia Pty Limited (No 5) [2020] FCA 637, para. [31]. Moreover where judges made decisions ‘on the papers’, the judge published written reasons.71x See, e.g., Kemp v. Westpac Banking Corporation [2020] FCA 437. The Federal Court does not appear to have used livestreaming during the pandemic where the public could anonymously watch proceedings.

In the Supreme Court of Victoria, the new practice was that all virtual hearings would be recorded and the transcript would be available in the usual way.72x Supreme Court of Victoria, Virtual Hearings: Practitioner’s Fact Sheet (April 2020) 4. See also, Supreme Court of Victoria, Supreme Court Changes in Response to COVID-19, 20 March 2020. The Supreme Court of NSW observed that ‘the usual concept of open justice is applicable to the Virtual Courtrooms’.73x Supreme Court of New South Wales, Virtual Courtroom Practitioner’s Fact Sheet, Version 1 (March 2020), p. 3. At the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, the Supreme Court of NSW conducted a major shareholder class action, opening addresses by only allowing the counsel addressing to be in the courtroom, with the lawyers, parties and public watching by a YouTube livestream.74x @LitigatorLegg (Twitter, 17 March 2020, 2.57 PM), https://twitter.com/litigatorlegg/status/1239762867642970117. The Supreme Court of Victoria has continued to livestream matters of considerable public interest.75x See, e.g., the Banksia Securities Class Action: Supreme Court of Victoria, Banksia Securities Limited Trial (Web Page), www.supremecourt.vic.gov.au/news/banksia-securities-limited-trial.

The experience of Australian courts during the pandemic was that open justice was limited through courtroom closures but that it could be replaced, some may even say expanded, through using technology for the public and the media to listen and see hearings from outside the courtroom. However, ease of access to the technology and the particular details for finding and accessing a hearing (i.e. court lists and electronic invitations or login details) impact whether the public and media can observe the justice system.

The principle of open justice is subject to exceptions.76x Hogan v. Hinch (2011) 243 CLR 506, p. 531, para. [21]. The exceptions include where it is necessary to secure the proper administration of justice in a particular case, such as to ensure procedural fairness. For instance, the family law courts are open courts, but there are prohibitions on reporting the names of parties, any person related to or associated with a party or witnesses.77x Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) s 121. On the one hand, online hearings can make it easy to protect sensitive information: with one click, observers can be cut off from the hearing. On the other hand, online hearings can make it more difficult to control the release of sensitive information. Justice Robert Beech-Jones of the NSW Supreme Court has expressed concern that online hearings do not allow the judge to control the courtroom in the way a normal face-to-face hearing would.78x Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law, University of New South Wales and Australian Institute of Administrative Law, ‘Fairness in Virtual Courtrooms’ (Webinar, 14 August 2020), www.youtube.com/watch?v=eectPocLjdI&feature=youtu.be.

These concerns show that the requirements of open justice in an online hearing need to be handled carefully with attention to the circumstances of each case.3.2 Procedural Fairness

Procedural fairness is an essential element of judicial proceedings. Robert French who is the former Chief Justice of High Court of Australia explained that:

Procedural fairness or natural justice lies at the heart of the judicial function. … It requires that a court be and appear to be impartial, and provide each party to proceedings before it with an opportunity to be heard, to advance its own case and to answer, by evidence and argument, the case put against it. According to the circumstances, the content of the requirements of procedural fairness may vary.79x International Finance Trust Co Ltd v. New South Wales Crime Commission (2009) 240 CLR 319, p. 354, para. [54].

In making adaptations to judicial process in keeping with the health recommendations to address the pandemic, procedural fairness remained a necessity.80x Legg, ‘The COVID-19 Pandemic’, supra n. 65.

In many Australian cases, the cure for the inability to have an in-person trial, and in particular in-person examination and cross-examination, was the use of AVLs. The emerging case law on the use of AVLs during the pandemic shows that courts have guarded procedural fairness vigilantly notwithstanding the changed nature of hearings.81x See, e.g., Australian Securities and Investments Commission v. Wilson [2020] FCA 873, paras. [37]-[38]; Quince v. Quince [2020] NSWSC 326, paras. [17], [20]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v. Rio Tinto Limited [2020] FCA 1721, paras. [49]-[60].

In some cases, the requirement of procedural fairness is embedded in legislation. For example, in NSW, the legislation addressing AVLs is the Evidence (Audio and Audio Visual Links) Act 1998 (NSW) (‘Audio Visual Links Act’). In civil litigation, an NSW court may direct that a person give evidence or make a submission by audio or AVL.82x Evidence (Audio and Audio Visual Links) Act 1998 (NSW) s. 5B(1). However, such a direction must not be made if:the necessary facilities are unavailable or cannot reasonably be made available, or

the court is satisfied that the evidence or submission can more conveniently be given or made in the courtroom or other place at which the court is sitting, or

the court is satisfied that the direction would be unfair to any party to the proceeding, or

the court is satisfied that the person in respect of whom the direction is sought will not give evidence or make the submission.83x Evidence (Audio and Audio Visual Links) Act 1998 (NSW) s. 5B(2).

Criminal proceedings in NSW are also dealt with in the Audio Visual Links Act. This Act has a default requirement, for criminal proceedings, of in-person attendance for ‘physical appearance proceedings’84x ‘Physical appearance proceedings’ include a trial, an inquiry into a person’s fitness to be tried and bail proceedings up to and including a person’s first appearance before a court in relation to an offence. and the use of AVL for proceedings other than physical appearance proceedings.85x Evidence (Audio and Audio Visual Links) Act 1998 (NSW) ss. 5BA, 5BB. However, the court may make a direction adopting an alternative approach, for instance utilizing AVL for ‘physical appearance proceedings’ if it is satisfied that this is in the interests of the administration of justice. An accused may also consent to the use of AVL for ‘physical appearance proceedings’.

During the pandemic, the NSW Parliament enacted the COVID-19 Legislation Amendment (Emergency Measures) Act 2020 No 1 (NSW)86x This legislation commenced on 25 March 2020. that introduced s. 22C into the Audio and Audio Visual Links Act. This new provision made the use of AVL for bail hearing mandatory, unless the court directed otherwise; and gave the court the power to direct an accused person, witness or legal practitioner to appear by AVL. Section 22C had the effect that AVL use would be more widespread, and the interaction between the core requirement of fairness and AVL use would need closer scrutiny. Previously, concerns around the fairness of AVL use could be addressed through an in-person hearing. The pandemic removed that option so that if relevant unfairness existed, then the alternative was no hearing for an indefinite period. Although the enactment of s. 22C was to enable more widespread use of AVL, a series of cases decided during the pandemic established that whether there would be unfairness to a party was still a key consideration. In Quince v. Quince87x Quince v. Quince [2020] NSWSC 326 (‘Quince’). and Haiye Developments Pty Ltd,88x [2020] NSWSC 732 (Haiye Developments). it was held that AVL would not be sufficient to ensure a fair trial in those cases.

Quince was a case decided during the pandemic, but prior to the introduction of s. 22C. Justice Sackar determined that the cross-examination of all the witnesses in the trial would take place by video link with the various parties in separate parts of Sydney. The case concerned allegations that transfers of shares purportedly executed by the plaintiff were forgeries and that the defendant implemented or procured that fraud. The plaintiff applied for the trial to be vacated as a matter of fairness on the basis that “the first defendant’s demeanour in answering these allegations will be crucial in assessing her credit, and in properly assessing her denials”.89x Id., para. [7]. This was a case where there was no circumstantial evidence, such as documentation, that aided in determining the facts. Sackar J observed[t]here will be many cases where the video link procedure will be more than fair and that issue will clearly have to be determined objectively on a case by case basis.90x Id., para. [19]. See also Brindley v. Wade (No 2) [2020] NSWSC 882, para. [11] (Hallen J) (‘Whether a direction of this kind would be unfair to any party is answered by an objective test that takes into account all the circumstances of the individual case’); Ascot Vale Self Storage Centre Pty Ltd v. Nom De Plume Nominees Pty Ltd [2020] VSC 242, para. [19] (McDonald J) (‘Whether trial by video link is appropriate is a matter to be determined on a case-by-case basis’).

However, “it would be antithetical to the administration of justice if the regime were to work an unfairness upon any party”.91x Haiye Developments [2020] NSWSC 732, para. [20]. On the facts of this particular case, the court held that an unfairness would be dealt to the plaintiff if they were not being given a full opportunity to ventilate the issues in the conventional way.

In Haiye Developments, Robb J considered the operation of s. 22C where a number of witnesses were located in China and AVL was sought to be employed for the taking of their testimony. Robb J explained:The Court’s power to make an order under s 22C of the Audio Visual Act is still confined by the prescription in subs (6) that a direction can only be given “if it is in the interests of justice” to do so. … It will ordinarily not be in the interests of justice for the Court to make a direction for an audio visual hearing if that would be unfair to any party to the hearing.92x Id., para. [52].

His Honour found that it would not be just to the plaintiffs to order that the witnesses in China give their evidence by AVL.93x Id., para. [64]. Central to Robb J’s finding was that there would be a need for a translator. Concern was also expressed as to the logistics in dealing with documentation and its impact on the witness’s credibility which, in turn, was central to the plaintiff’s case. Robb J reasoned as follows:

It is an extremely difficult exercise for the Court to make sound judgments as to the credibility of witnesses who are cross-examined on crucial issues – particularly as to the making of oral statements – when the cross-examination must be interpreted from the English to the Chinese and then from the Chinese to the English. There is extensive scope for misunderstanding and error concerning the correct interpretation of the original words the subject of the evidence, and this is compounded by the need for a series of interpretations. It is preferable for the Court to be able to make the necessary judgments face-to-face with the witnesses giving the evidence, but it is in some ways more crucial for the whole exercise to proceed smoothly and without dislocation, and with the witnesses and the interpreters having a sufficiently confident and functional relationship.94x Id., para. [60]. See contra Auken Animal Husbandry Pty Ltd v. 3RD Solution Investment Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1153, para. [56] (Stewart J) (agreeing with the difficulty of a judge making an assessment of a witness’s credibility when the witness is giving evidence through an interpreter but stating ‘in my experience such difficulties are not made significantly worse by the fact of the evidence being given by AVL’.)

In the Federal Court of Australia, AVL was also used to allow the courts to continue to operate during the pandemic. The court may, for the purposes of any proceeding, direct or allow testimony to be given by video link, audio link or other appropriate means.95x Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s. 47A(1). The court must not exercise that power unless it is satisfied, essentially, that all key persons can see and hear one another, regardless of where they are located.96x Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s. 47C(1). As with NSW, the discretion has been described as a broad one with the determining consideration being the interests of justice.97x Australian Securities and Investments Commission v. Wilson [2020] FCA 873, para. [6] citing Director of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v. Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2015] FCA 627; (2015) 231 FCR 531, pp. 536-537, para. [16].

Equally, it is important to note that in Davidson v. Suncorp-Metway Limited98x [2020] FCA 879. (decided in June 2020), Jackson J rejected a submission from the plaintiff ‘that he considered that he has a right to an in-person hearing’. Jackson J explained:

That is, with respect, not correct. There is no unqualified and absolute right to an in-person hearing, because … the court [may] order that evidence and submissions be made over video or audio links, and the court has power to do that on the application of a party, or on its own initiative. Section 47C of the Act, however, sets out certain conditions that must be satisfied …. In broad terms, the conditions are that the court must be satisfied that if the matter proceeds by video link or audio link that all eligible people, both in the court room and at remote locations, are able to see and hear each other.99x Davidson v. Suncorp-Metway Limited (No 2) [2020] FCA 879, para. [9].

The issue of utilizing AVL to allow trials to continue was also discussed by the Federal Court in the context of applications for an adjournment. The two leading decisions were Capic v. Ford Motor Company of Australia Limited (Adjournment)100x [2020] FCA 486 (‘Capic’). (a class action) and Australian Securities and Investments Commission v. GetSwift Limited101x [2020] FCA 504 (‘GetSwift’). (civil penalty proceedings).

In Capic, Perram J determined that the need to balance the need for the courts to continue to dispense justice with avoiding the health risk posed by court attendance “suggest a mode of trial conducted over virtual platforms from participants’ homes”, unless the requirements of the overarching purpose102x The overarching purpose is set out in Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s. 37M and specifies the need to “facilitate the just resolution of disputes: (a) according to law; and (b) as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible”. and considerations of fairness to the parties meant that a virtual solution was not feasible.103x Capic [2020] FCA 486, para. [6]. See also Australian Securities and Investments Commission v. Rio Tinto Limited [2020] FCA 1721, paras. [46]-[47]. Similarly, Lee J in GetSwift stated that an inability to conduct a hearing in the traditional manner did not prevent the proper exercise of the judicial function.104x GetSwift [2020] FCA 504, para. [7]. His Honour added that while the court must continue to function, “fundamental to the discharge of that role is ensuring that cases are determined justly”.105x Id., para. [9].

In Capic, the respondent submitted that the cross-examination of witnesses over AVL was unacceptable. Perram J disagreed and observed that judicial statements voicing concern about cross-examination over AVL were not made in the context of a pandemic causing the physical closing of courtrooms, nor were they made with the benefit of seeing cross-examination on platforms such as Microsoft Teams, Zoom or Webex. His Honour further stated:[m]y impression of those platforms has been that I am staring at the witness from about one metre away and my perception of the witness’ facial expressions is much greater than it is in Court[.]106x Capic [2020] FCA 486, para. [19]. See also Auken Animal Husbandry Pty Ltd v. 3RD Solution Investment Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1153, para. [49] (Stewart J).

A similar sentiment was expressed by Lee J in GetSwift:

To the extent that demeanour does play an important role in assessing the evidence of witnesses, then my experience, particularly in the recent trial that I conducted, is that there is no diminution in being able to assess the difficulty witnesses were experiencing in answering questions, or their hesitations and idiosyncratic reactions when being confronted with questions or documents. Indeed, I would go further and say that at least in some respects, it was somewhat easier to observe a witness closely through the use of the technology than from a sometimes partly obscured and (in the Court in which I am currently sitting) distant witness box.107x Australian Securities and Investments Commission v. GetSwift Limited [2020] FCA 504, para. [33].

The experience of ‘trial by zoom’ was also commented on by Dixon J in the Victorian case of Long Forest Estate Pty Ltd v. Singh108x [2020] VSC 604. dealing with breach of contract in relation to farm land; a trial that involved substantial credit issues. Dixon J commented that he

did not find assessment of credit more challenging than it would have been if the various witnesses were physically in court and gave evidence from the witness box. Counsel did not appear to be impeded in their work. Consistent with recent observations made by other judges, I found ample opportunity to assess demeanour and determine credibility for each witness in the virtual hearing. There were other advantages flowing from the relative speed at which witnesses were able to navigate the electronic court book. … [I]ssues of credit ought not, in and of itself, be a basis to conclude that a proceeding must be heard as an in-person trial.109x Id., paras. [22]-[23] (citations omitted). See also Porter v. Mulcahy and Co Accounting Services Pty Ltd (Ruling) [2020] VSC 430, para. [26].

Not all judges share this view. In Rooney v. AGL Energy Limited (No 2), Snaden J granted an adjournment in an employment law case, observing that remote hearing technology was:

a good and, in many instances, necessary “Plan B”. However, the available technology cannot fully replicate the court room environment that is so often central to an adversarial system of civil justice. In my experience, the technology inhibits (if not prohibits) the cadence and chemistry—both as between bar and bench, and bar and witness box—that personify well-run causes. Those are traditional forensic benefits of which litigants ought not too lightly be deprived…

Apart from the issue of fairness, Snaden J also observed that technology was not necessarily efficient:

[T]he technology often begets delay, particularly when documents are to be supplied remotely. Although broadly reliable, it is not uncommon for connections to be momentarily of poor quality, occasionally to the point that they are unusable. All of these factors influence the user experience of a justice system from which all litigants are entitled to benefit.110x Rooney v. AGL Energy Limited (No 2) [2020] FCA 942, para. [18].

However, it must also be remembered that there has been a learning process with AVL. The courts have accepted that they now have more experience with using AVL, including taking contentious evidence by AVL.111x See, e.g., Universal Music Publishing Pty Ltd v. Palmer [2020] FCA 1472, para. [32]; Auken Animal Husbandry Pty Ltd v. 3RD Solution Investment Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1153, paras. [49]-[50]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v. Wilson (No. 2) [2021] FCA 808, paras. [34], [44]. The same applies to the legal profession. Advocates have had to learn and adapt to AVL so that they are now more comfortable and skilled in its use. Courts and professional bodies have assisted with this process.112x See, e.g., Federal Court of Australia, National Practitioners and Litigants Guide to Online Hearings and Microsoft Teams (2 April 2020; Updated 26 May 2020); New South Wales Bar Association, Protocol for Remote Hearings, (Web Page), https://nswbar.asn.au/uploads/pdf-documents/remote_hearing_protocol.pdf; Australian Advocacy Institute, Remote Advocacy Skills in the Age of COVID-19 (Web Page), https://vimeo.com/415727777. The remaining concern is the self-represented litigant who must not only familiarize themselves with law and procedure, but also technology.113x Legg & Song, supra n. 65, pp. 160-161. Equally, the use of AVL may be more familiar to a self-represented litigant who may have used it in other areas of life and business, compared to the foreign experience of a court hearing.114x Legg & Bell, supra n. 24, p. 150.

In summary, Australian courts are able to use AVL, including proprietary technology such as Microsoft Teams, Zoom or Webex, to facilitate hearings, indeed entire trials. However, the availability and conduct of remote or online hearings turns on the court being able to ensure procedural fairness. This does not mean that a hearing or trial can only be fair when conducted in the same manner as it has been historically: that is, in person. Rather, the particular circumstances and needs of the matter must be considered to ensure that the hearing operates in a fair manner, namely with an opportunity to be heard that includes putting forward and challenging evidence and submissions.115x Legg, supra n. 65. Technology may facilitate or undermine procedural fairness.3.3 Access to Justice

The extent to which the use of technology variously promotes or hinders access to justice has been contentious. There is a ‘digital divide’ in Australia with substantial numbers of households not having home Internet access, including a higher proportion of Indigenous Australian households.116x Australian Digital Inclusion Index, ‘Digital Inclusion in Australia’ (Web Page), https://digitalinclusionindex.org.au/about/about-digital-inclusion/ (Noting that 1.25 million (or 14%) of Australian households lacked internet access at home in 2016-2017). People with disability, from non-English speaking backgrounds, and older people are all less likely to access the Internet.117x Id. Remote hearings in particular may also present problems in terms of whether the participant has a suitable, private location from which to access the hearing or whether they will have the means to communicate with their lawyer (if they have one) and access documents. On the other hand, there may be significant savings in terms of travel and legal costs and other benefits associated with not having to be physically present in the courtroom.118x This had been noted pre-pandemic in relation to the use of AVL: see, e.g., Law Society of New South Wales, Media Release, ‘Technology should not replace courts and transparent justice’, 26 June 2017 (P. Wright).

An early study of Australian courts during the pandemic confirmed that digital exclusion is a real barrier to participating in online hearings.119x Grata Fund, supra n. 52. People who experience digital exclusion lacked the basic hardware, software, bandwidth and data to participate effectively in court events, with problems being most acute for self-represented litigants.120x Id., pp. 3-15.

In family law proceedings, the move to online hearings may be potentially beneficial for litigants, particularly for safety and security,121x E.g., comments of COVID-19 Registrar Brett McGrath of the Family Court, quoted in K. Allman, ‘Lunch with Family Court National COVID-19 Registrar Brett McGrath’, Law Society Journal, no. 67, 2020, p. 27. and for saving travel time and associated costs such as missing work or finding childcare. Notably, though, litigated family law disputes tend to involve parties with multiple complex needs and co-occurrence of complex problems such as family violence, addiction and mental health issues.122x R. Kaspiew et al., Evaluation of the 2006 Family Law Reforms (Report, Australian Institute of Family Studies, December 2009), pp. 29-30; R. Kaspiew et al., Evaluation of the 2012 Family Violence Amendments: Synthesis Report (Report, Australian Institute of Family Studies, October 2015), p. 16; Family Law Council, Families with Complex Needs and the Intersection of the Family Law and Child Protection Systems: Terms 1 & 2 (Interim Report, June 2015). Parties typically have fewer resources than those engaged in commercial litigation; correspondingly, family law practitioners tend to operate in small firms or as sole practitioners who may also lack the resources of their large-firm counterparts.

Whether an online hearing would be too onerous for parties for reasons such as disability, lack of access to technology or being self-represented has been left to individual judicial officers to determine, and no particular guidance has yet emanated from an appellate court. In Sayid & Alam,123x Sayid & Alam [2020] FamCA 400. Harper J held that the self-represented mother would be too disadvantaged by undertaking a 6-day trial remotely. In Harlen & Hellyar (No. 3),124x Harlen & Hellyar (No. 3) [2020] FamCA 560. Wilson J also allowed a last-minute adjournment of a trial on the basis of, among other things, the applicant’s computer illiteracy and the need for an interpreter. Walders & McAuliffe125x Walders & McAuliffe [2020] FCCA 1541. listed several factors that militated against undertaking the hearing remotely: the respondent was under a disability and was represented by a litigation guardian, substantial cross-examination would be required due to disputed issues of fact and there were significant issues of credit involved.126x Id., para. [13]. The judge therefore concluded thatThere would be real concerns and issues as to the ability of one or both parties engaging fully and properly in the process if it was conducted as a remote hearing[.]127x Id.

-

4 Australian Court Responses to COVID-19 Beyond Technology

This article focuses on the use of technology to improve court efficiency in Australia, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of course, technology is not a panacea. When reflecting on Australian courts’ response to the pandemic, it is important to take note of the ways in which technology has been combined with other innovative measures in order to keep the justice system functioning at something approaching its usual capacity.

Most of Australia initially experienced a relatively short period of severe restrictions, with most jurisdictions able to resume jury trials and some other face-to-face hearings by mid-June 2020. However, there have been exceptions in the case of jurisdictions that already faced pre-pandemic backlogs, and those who have gone into extended second- and third-wave lockdowns. For example, by October 2020, Victoria was in the midst of a second wave of infections and faced a backlog of around 750 trials in the County Court (a mid-tier court) alone.128x County Court of Victoria, Criminal Division, Emergency Case Management Model Protocol 5 – Emergency Protocol COVID 19 (2020) [2.2]. In August 2021, the Victorian Court of Appeal observed that the ‘enormous and intimidating’ backlog ‘will take years to rein in’.129x Worboyes v. The Queen [2021] VSCA 169, para. [22] (Priest, Kaye & T. Forrest JJA). The family law courts were also already facing a backlog pre-pandemic and had launched a campaign to try and clear cases identified as having been in the court system for more than 18 months.130x Family Court of Australia, ‘Media Release – Hundreds of NSW Families Encouraged to Resolve Lengthy Family Law Disputes During the Court’s Summer Campaign’, 2 March 2020, www.familycourt.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/fcoaweb/about/news/mr020310. The campaign involved a system of mass call overs and was quickly shut down with the implementation of pandemic-related restrictions. To take another example, with NSW in a months-long lockdown in late 2021, their justice system was experiencing long delays, with some defendants awaiting trial for 12 months longer than usual.131x T. Mills, ‘COVID and the Courts: Jury Trials on Hold Again, Backlog Still Looms’, The Age, 30 August 2021.

It is worth noting the four procedural measures Australian courts have taken to reduce the backlog caused by the pandemic.

First, the use of non-binding neutral evaluations (NNEs). In the taxonomy of legal disputes introduced in Part II of this article, NNE fits within the ADR phase of a dispute, albeit very close to the judicial determination phase. In NNE, a judge or other party appointed by the court provides an analysis of the key issues and a non-binding evaluation of the strength of each party’s case.132x See Seals v. Williams [2015] EWHC 1829 (Ch), paras. [3], [6]. The process occurs at a later stage of proceedings, as opposed to the similar process of early neutral evaluation.133x County Court of Victoria, Non-binding Neutral Evaluation (NNE), Information Sheet, 26 March 2020. Before the pandemic, NNEs were not widely used in Australia. In March 2020, the County Court of Victoria began offering NNE via electronic means to parties who were ready to proceed to trial, but whose trial had been delayed by COVID-19 restrictions.134x Id. In March 2021, the offering of NNE was expanded to include the Medical List in the County Court.135x County Court of Victoria, Medical List: Alternative Dispute Resolution Processes, Notice to Practitioner, 9 March 2021. NNEs are an example of technology being combined with procedural innovation to increase court capacity.

The other three measures we discuss here fall within the ‘judicial determination’ stage of the dispute resolution process.

The second measure is the implementation of triage systems. Several courts have developed criteria for prioritizing or triaging hearings. Different jurisdictions have given priority to matters in which a party or witness has limited life expectancy;136x District Court of Western Australia, Public Notice-COVID-19: Amendment to Practice Direction 17 – Change in Practice due to COVID-19, 14 July 2020; County Court of Victoria, Criminal Division, Emergency Case Management Model Protocol 5 – Emergency Protocol COVID 19 (2020), 6.1(d). criminal trials where the defendant is in custody;137x Local Court of New South Wales, Chief Magistrate’s Memorandum No 13 COVID-19 Arrangements, 1 July 2020. and matters involving family violence.138x Id. See also, Family Court of Australia, ‘COVID-19 Update: Reminder that Family Law Disputes Impacted by the Pandemic may be Dealt with Through the Courts’ COVID-19 List’, 20 August 2021, (Web Page), www.familycourt.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/fcoaweb/about/news/mr200821. Victoria’s County Court is giving priority to preliminary rulings that might lead to the matter resolving without a trial, or that might reduce the length of the trial.139x County Court of Victoria, Criminal Division, Emergency Case Management Model Protocol 5 – Emergency Protocol COVID 19 (2020), 6.1(a). The family law courts created a ‘COVID-19 list’ to triage urgent applications arising as a result of the pandemic (for instance, where a child could no longer travel to see a parent).140x Family Court of Australia, ‘Media Release – The Courts Launch COVID-19 List to Deal with Urgent Parenting Disputes’, 26 April 2020.

Third, the introduction of ‘fast-track’ mechanisms. The Victorian Supreme Court has introduced a ‘fast-track’ for homicide cases. To ease the backlog in the Magistrate’s Court, issues of disclosure and evidence that would usually be dealt with by that court during committal proceedings can instead be managed by the Supreme Court.141x Supreme Court of Victoria, Fast-tracking Homicide Matters to the Supreme Court, originally published 25 March 2020, first revision 20 August 2020, www.supremecourt.vic.gov.au/law-and-practice/areas-of-the-court/criminal-division/fast-tracking-homicide-matters-to-the-supreme. This is a noteworthy innovation because it involves a higher court relieving the workload of a lower court; we are used to seeing work flow in the opposite direction.

Finally, some Australian courts have also tried to increase the use of ‘judge-alone’ trials for serious criminal matters. This measure has been sufficiently widespread to warrant further discussion.4.1 Criminal Trials: Juries and Judges Alone

Most Australian jurisdictions suspended jury trials (or, at least, stopped listing new jury trials) shortly after the pandemic was declared. Jury trials had resumed in most jurisdictions by mid-to-late 2020, although jurisdictions that have experienced subsequent waves of community infections have had to suspend new jury trials again.142x For example, in NSW, the District Court stopped listing new jury trials in certain locations from 25 June 2021 and, at the time of writing, was listing no new jury trials: District Court of New South Wales, ‘Downing Centre and John Maddison Tower Restrictions until 2 July 2021’ (Website content posted 25 June 2021); District Court of New South Wales, ‘COVID-19 Update – 19 August 2021 – District Court’ (Website content, posted 19 August 2021). Both announcements are available at District Court of New South Wales, District Court Updates COVID-19 (Coronavirus) (Web Page), www.districtcourt.nsw.gov.au/district-court/covid-19--coronavirus-/district-court-updates-covid-19--coronavirus-.html. Where jury trials have resumed, they have often been accompanied by social distancing precautions such as using two adjacent courtrooms for a single trial. Other measures have included increased cleaning of common areas, health screening questions, COVID-19 tests for jurors who develop symptoms and increased consideration of applications to be excused from jury service because of the potential impact of COVID-19.143x See Juries Victoria, Juror Safety during COVID-19 (Webpage), www.juriesvictoria.vic.gov.au/juror-safety-during-covid-19; Queensland Courts, ‘Juror Safety During the COVID-19 Response’ (24 August 2020), www.courts.qld.gov.au/jury-service.

Several jurisdictions have sought to increase their reliance on judge-alone trials to reduce the potential backlog of criminal trials. While not a technology-based solution, this is worth noting as an important part of Australian courts’ response to the challenges of the pandemic.

Judge-alone trials, at the election of the defendant, were already an established practice in some Australian jurisdictions. There is little constitutional restraint on the ability of the States to abrogate the common law right to trial by jury. Section 80 of the Australian Constitution mandates a trial by jury for indictable Commonwealth offences. This constitutional guarantee, however, does not apply to offences against State (rather than Commonwealth) law, which include the majority of offences against the person. Nor does the constitutional guarantee apply to non-indictable Commonwealth offences.

The most dramatic abrogation of trial by jury during the pandemic occurred in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). The ACT passed legislation authorizing a court to order a trial by judge alone without the consent of the defendant. A new section, inserted by the COVID-19 Emergency Response Act 2020 (ACT) provided that during the COVID-19 emergency,The court may order that the proceeding will be tried by judge alone if satisfied the order –

will ensure the orderly and expeditious discharge of the business of the court and

is otherwise in the interests of justice.144x Supreme Court Act 1933 (ACT) s. 68BA.

This section was used several times to order a trial by judge alone.145x R v. UD (No 2) [2020] ACTSC 90; R v. Coleman [2020] ACTSC 97; R v. IB (No 3) [2020] ACTSC 103. However, the provision attracted robust criticism from the legal profession for removing the right of an accused to a trial by jury.146x Australian Capital Territory Law Society, Law Society Condemns ACT Government’s Removal of Right to Trial by Jury (Media Release, 2 April 2020), www.actlawsociety.asn.au/article/-law-society-condemns-act-government-s-removal-of-right-to-trial-by-jury; Law Council of Australia, Law Council of Australia President, Pauline Wright, Statement Regarding the Right to Jury Trials (Media Release, 3 April 2020). One defendant commenced a constitutional challenge to the provision in the High Court.147x See UD v. The Queen [2020] HCATrans 61 (28 May 2020). Before that challenge was determined, the section was repealed.148x COVID-19 Emergency Response Legislation Amendment Act (No 2) 2020 (ACT). The second reading speech for the Bill affecting that repeal explained that it was only ever intended as a temporary measure and was not longer needed because the ACT was in a position to recommence jury trials.149x Australian Capital Territory, Parliamentary Debates, 18 June 2020, 1310.

Other jurisdictions have taken a softer approach, expanding the circumstances in which a judge-alone trial can be ordered with the consent of the accused. Victoria, which had previously allowed trial by judge-alone only in a limited category of cases, extended the possibility to the trial of any indictable offence.150x Criminal Procedure Act 2009 (Vic) Ch. 9, inserted by the COVID-19 Omnibus (Emergency Measures) Act 2020 (Vic) and repealed on 26 April 2021. The Victorian provisions have been interpreted in DPP v. Combo [2020] VCC 726; DPP (Vic) v. Truong [2020] VCC 806; DPP (Vic) v. Carlton (a pseudonym) [2020] VCC 1272 and DPP (Vic) v. Jacobs (a pseudonym) [2020] VCC 125. In NSW, a new section of the Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW)151x Section 365, inserted by the COVID-19 Legislation (Emergency Measures) Act 2020 (NSW). The factors relevant to the making of an order under s. 365 have been considered in R v. Johnson [2020] NSWDC 153 and R v. BD (No 1) [2020] NSWDC 150. allows the court to order a trial by judge alone on its own motion and against the wishes of the prosecution, but with the consent of the accused, if the court considers this in the interests of justice.

As the experience in the ACT shows, any derogation from the common law right to trial by jury is bound to be controversial. -

5 Conclusion

Overall, Australia’s experience has showed that technology can be used to keep the court system operating at an acceptable standard of justice, fairness and openness. Much credit is due to the legal profession and court staff. At a recent (virtual) ceremony for the admission of new practitioners, NSW Chief Justice Tom Bathurst reflected:

Throughout history, our profession has proved itself adept at change and never more so than now. We transitioned to a virtual system of justice at a previously unimaginable speed. As you are experiencing right now, dining tables have become the new bar tables, family dogs the new courtroom security, and interrupting children the new rowdy members of the public. This transformation was only possible due to the commitment of the profession to ensuring that the wheels of justice continue to turn. This is something for which we should all be immensely proud.152x Chief Justice T.F. Bathurst, Admission Ceremony, August 2020, www.supremecourt.justice.nsw.gov.au/Documents/Publications/Speeches/2020%20Speeches/Bathurst_20200800.pdf.

Crucially, technology has only been able to deliver positive results when supported by adequate resourcing. This includes high-quality software and hardware, fast Internet, responsive ITS support and ongoing maintenance and a range of training options for users. Just as importantly, court staff must have the time and expertise to support court users in navigating the technology, conducting technical rehearsals and solving problems.

For example, concern has been expressed that the transition to online hearings will detrimentally impact upon the capacity of lawyers to meaningfully engage with their clients both before and during hearings. There is a real validity to this concern. A client who is accessing a hearing only through their phone will be severely restricted in communicating with their lawyer if they are dependent on that same phone to use WhatsApp. The ability of that lawyer to go through documentary evidence with that client before a hearing is similarly greatly diminished.

However, where the full range of digital justice systems are embraced, these problems may be greatly reduced. This is particularly so where quality secondary-support technologies are utilized. The opportunity exists for dedicated case and evidence management systems to be developed, so that lawyers can easily and securely share documents with clients and other lawyers remotely. Where those systems are linked to modern e-filing systems, this can have significant benefit for court capacity by reducing the administrative burden on lawyers, registry staff and judicial officers.

The pandemic has showed that technology can have an ongoing place in improving court efficiency and accessibility. Yet, as this article has explored, there must be a balance between embracing technology and preserving the core characteristics of the judicial function. As our examples show, any technological solution must be applied sensitively with a nuanced regard to the circumstances of the case and the parties. To date, operating under emergency conditions, these decisions have largely been made in an ad-hoc manner with little in the way of general guidance. For a justice system to make the most effective use of technology to increase court capacity, guidance of this kind (whether in the form of legislation, court rules or practice notes or the development of jurisprudence) is necessary.

There is value, too, in keeping a record of the measures that have been taken, their efficacy and their compatibility with both the dispute resolution and the social governance functions of the judiciary. This article is a contribution to that endeavour. -

1 ‘Court Capacity’, UK Parliament (Web Page), https://committees.parliament.uk/work/481/court-capacity/.

-

2 See, e.g. Remote Courts Worldwide, https://remotecourts.org/; K. Puddister & T. A. Small, ‘Trial By Zoom? The Response to COVID-19 by Canada’s Courts’, Canadian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 53, 2020, p. 373; P. Cooper, Looking Ahead: Towards a Principled Approach to Supporting Participation, in J. Jacobson & P. Cooper (Eds.), Participation in Courts and Tribunals: Concepts, Realities and Aspirations, Bristol University Press, Bristol, 2020, pp. 141, 160-165; P. Magrath, ‘Coronavirus, the Courts and Case Information’, Legal Information Management, Vol. 20, 2020, p. 126.

-

3 The language of ‘court capacity’ is not widely used in Australia. However, concerns of the kind that have provoked this inquiry (the cost, time and availability of judicial dispute resolution) are certainly familiar. Australian discussions about these concerns tend to use language such as ‘efficiency’ and ‘access to justice’ rather than ‘court capacity’.

-