-

1 Design Thinking – Stakeholder Focused

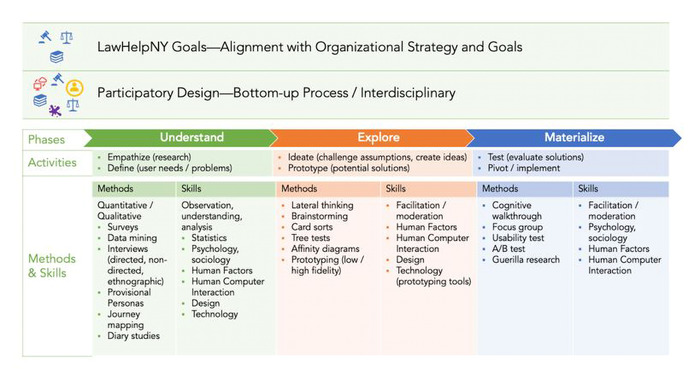

Additionally, as the following diagram ‘Participatory Design – Method Agnostic’ illustrates, along with aligning with the organization’s overall vision, strategy and goals, participatory design is an approach that can encompass many different methods. The methods, many requiring specialist education, training and expertise, do not rise above the mandate to employ a participatory approach.

-

2 Participatory Design – Method Agnostic

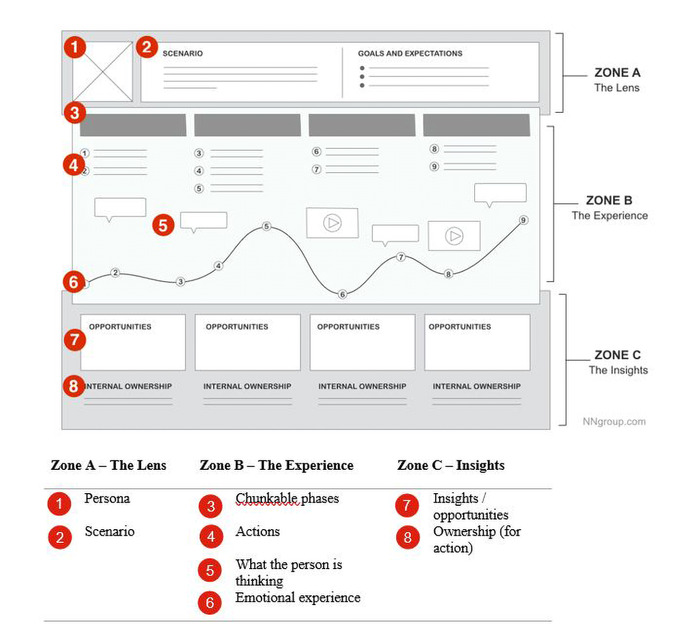

Journey-mapping is a useful method for a participatory design approach as it enables multiple stakeholders to engage and create a shared organization or inter-agency vision, coalescing around the needs of the end user. In fact, it immediately provides an opportunity to reach consensus on priorities when there may be multiple end users, multiple case types. Where the end user traverses between organizations as they navigate the civil justice system, it is a way to identify opportunities for improving processes, services and solutions in new ways.

-

3 Journey Map Structure – Nielsen Norman Group

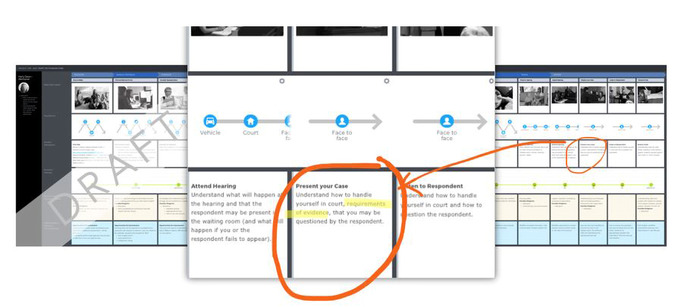

The following snapshot is from a DRAFT journey map, based on existing knowledge of the protective order process in Missouri. The call-out serves to illustrate the challenge for a petitioner, when they appear before the court to request a permanent restraining order, and the requirements of evidence that they may not be prepared to meet. How might the team creating this journey map help the petitioner address this challenge? Is there an opportunity for a process improvement ‘upstream’ at the point where the petitioner first seeks help?

-

4 DRAFT Journey Map – Petitioning for a Protective Order, Missouri

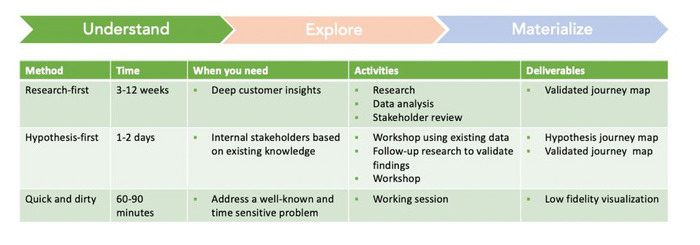

The reality of designing any new process, service or solution is that resources may be constrained. The following table demonstrates that journey-mapping can be undertaken using lean research methods, beginning with a DRAFT hypothetical journey map that is then validated with end users. The focus still remains on how you will engage stakeholders in the process, through all phases, including the ‘thinkers’ or subject-matter experts, together with the ‘makers’, researchers, designers, technologists and, of course, the end user you are seeking to serve.

-

5 Journey Mapping on a Budget

In conclusion, participatory design has the potential to contribute to successful ODR solutions when, first, the goals for the solution align with your organization’s overall strategy; second, understanding that the approach can be used in designing policy, process or solutions; and, third, when employing a participatory design approach, you consider extending the breadth of your stakeholder group to include end users and other disciplines (research, design, technology) throughout the process. Finally, it needs to be remembered that it is an approach that can accommodate different budgets and timelines and that the method must always serve the approach.

-

1 The Law Society of England and Wales, ‘Technology, Access to Justice and the Rule of Law: Is Technology the Key to Unlocking Access to Justice Innovation?’, The Law Society, 16 September 2019.

-

2 Linda Warren Seely, Amber Ivey, ‘ODR Guardrails’, Conference presentation 2019 International ODR Forum, 29 October 2019.

-

3 Wikipedia.

-

4 Wikipedia.

-

5 Usability.gov. Benefits of User-Centered Design. Usability-gov., Available at: https://www.usability.gov/what-and-why/benefits-of-ucd.html, 15 November 2019.

-

6 M. Hagan, ‘Participatory Design for Innovation in Access to Justice’, Dædalus,Winter 2019, pp. 120-127.

-

7 Ibid.

-

8 S. Bødker, ‘A Short Review to the Past and Present of Participatory Design’, Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 2010, 22(1), pp. 45-48.

Using a participatory design approach supports initiatives seeking to advance access to justice, whether they be policy, service or solution-oriented. A participatory design approach can be used effectively irrespective of whether your perspective towards access to justice is as a court employee, a private practitioner (attorney, mediator), a legal aid or human service agency professional, an academic or a technologist.

As a working definition, access to justice may be defined as

a fundamental component of the rule of law, a functioning economy and social inclusion. Being able to access high quality legal advice that is timely and affordable is a key part of this right.1xThe Law Society of England and Wales, ‘Technology, Access to Justice and the Rule of Law: Is Technology the Key to Unlocking Access to Justice Innovation?’, The Law Society, 16 September 2019.

The imperative to address access to justice in the civil legal system is well understood by the community of practitioners from the many organizations that participate in it. The number of stakeholders and the range of perspectives further reinforce the value of using a participatory design approach. During her session on ODR Guardrails,2xLinda Warren Seely, Amber Ivey, ‘ODR Guardrails’, Conference presentation 2019 International ODR Forum, 29 October 2019. Linda Warren Seely emphasized the importance of an inclusive approach in establishing ODR principles, concluding that “the more people involved, the better the end product will be”.

And so, what is participatory design, and how can it help?

Wikipedia defines it as follows:

Participatory design (originally co-operative design, now often co-design) is an approach to design attempting to actively involve all stakeholders (e.g. employees, partners, customers, citizens, end users) in the design process to help ensure the result meets their needs and is usable. Participatory design is an approach which focuses on processes and procedures of design and is not a design style.3xWikipedia.

It is important to make a distinction between participatory design and user-centred design.

User-centered design (UCD) … is a framework of processes … in which usability goals, user characteristics, environment, tasks and workflow of a product, service or process are given extensive attention at each stage of the design process.4xWikipedia.

It is well known that the benefits of this approach extend beyond providing an experience that is more efficient, effective and satisfying for the end user and that return on investment can measured in reduction of errors, cost savings and productivity.5xUsability.gov. Benefits of User-Centered Design. Usability-gov., Available at: https://www.usability.gov/what-and-why/benefits-of-ucd.html, 15 November 2019.

In her recent article in Dædalus, Margaret Hagan challenges whether a user-centred design approach is sufficient, referring to projects that have used this approach and yet have failed to achieve the intended benefits for both the organization and the end users.6xM. Hagan, ‘Participatory Design for Innovation in Access to Justice’, Dædalus,Winter 2019, pp. 120-127. She goes on to share recent projects undertaken by the Stanford Law School Legal Design Lab, where they experimented with a participatory design approach, comparing resource-intensive and lean research methods and describing the potential for this approach to identify solutions that provide real and lasting benefits to users.7x Ibid.

Participatory design has its roots in systems design in Scandinavia with a socio-technical design focus. Its early proponents include Kristen Nygaard and Olav-Terje Bergo, and their work with the Norwegian Iron and Metal Workers Union in the 1970s.8xS. Bødker, ‘A Short Review to the Past and Present of Participatory Design’, Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 2010, 22(1), pp. 45-48. It involves an immersive approach to problem definition, solution exploration and implementation. With the rise of computing, in particular, personal computing in the 1970s and 1980s, and the associated human factors and usability disciplines, the method evolved and was adapted for business by David M. Kelly (founder of IDEO in 1991). ‘Design Thinking’ is now ubiquitous, and, while it employs similar phases and many of the same research methods used in participatory design, it has been packaged and commercialized, perhaps to the detriment of the value that a return to a more authentic participatory design approach can provide.

As the following diagram, ‘Design Thinking – Stakeholder Focused’, shows, it is not sufficient to follow a design-thinking methodology, even when it is person-centred, if this excludes all stakeholders from the understanding, exploring and materializing phases.