-

1 The ‘Crisis of Justice’

Getting cases decided in court within a reasonable time is a problem in many countries and in some cases can present a veritable crisis of justice. In Europe, time to get cases decided has significant differences from country to country, according to the 2017 EU Justice Scoreboard.1x https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/justice_scoreboard_2017_en.pdf.

In Brazil the numbers are not encouraging. According to the report Justice in Numbers 2018, from the National Council of Justice, the time required to get cases decided and the decision enforced is nearly 9 years in Federal and State Courts.2x www.cnj.jus.br/files/conteudo/arquivo/2018/08/44b7368ec6f888b383f6c3de40c32167.pdf.

An alternative that is commonly used in judicial proceedings (at least in many civil law countries) is to hold a preliminary hearing in order to encourage a settlement. Brazil is one of the countries that adopt this strategy, in which Civil Procedure Rules have established, in article 334, that after the defendant is notified, there will be a hearing in order to help the parties reach a settlement.

However, even when there is an attempt to resolve the dispute by including an element of mediation or negotiation in a hearing, the hearing is frequently scheduled for months or years later, and the conflict remains active.

This article aims to analyse online dispute resolution as an efficient alternative to resolve the crisis of justice in Brazil. -

2 The ‘Crisis’ of Justice and the New Systems of Dispute

The problems found in civil justice led to a response known as the design of systems of dispute (DSD) approach.3xTo know more, see W. Ury, J.M. Brett, & S.B. Goldberg, Getting Disputes Resolved: Designing Systems to Cut the Costs of conflict, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1988. The premise of DSD is that for each conflict there may be an adequate mechanism to solve it. Sometimes there is more than one channel for that, and lawyers and parties must focus on their interests in order to determine the best channel to solve the conflict.

In the same context, the use of alternative dispute resolution was a response to the crisis of adjudication, serving as an efficient method to solve disputes and the necessity of adequate channels to that. In 1976, during the Pound Conference Frank Sander defended the idea of ‘Multi Door Courts’,4xF.E.A. Sander, ‘Varieties of Dispute Processing’, Federal Rules Decisions, Vol. 77, 1976, pp. 111-123. which means that courts should be a place where parties could find different forms of dispute resolution, each of which is represented as a different door. Consequently, adjudication is not the only way of resolving a dispute. Alternative dispute resolution may be a better way to find a solution, and could include mediation, conciliation and arbitration, for example.

In the United States, alternative dispute resolution has an important role in the system of justice,5xBringing a critical view of the role of agreements, O.M. Fiss, ‘Against Settlement’ (1984). Faculty Scholarship Series. 1215. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/1215. and in the Department of Justice, around 75% of the proceedings ended in agreements.6xThe United States Department of Justice, ‘Alternative Dispute Resolution at the Department of Justice’, available at: https://www.justice.gov/olp/alternative-dispute-resolution-department-justice.

In Brazil, Civil Procedure Rules establish access to justice as a fundamental principle of civil procedure in article 3. However, we can say that access to justice in Brazil does not only means the right to access a fair judgment by a member of Judiciary Power.

Article 3 shows that access to justice is the right to a fair resolution of the dispute, which will not necessarily come from adjudication. Besides stating that anybody may file a claim before the Judiciary Power, paragraph 1 establishes that arbitration is allowed, and paragraph 2 defines a duty to State to promote a consensual dispute resolution.7xBrazilian Procedure Code: Art. 3. Neither injury nor threat to a right shall be precluded from judicial examination.§ 1 Arbitration is allowed, in accordance with statutory law.

§ 2 The State must, whenever possible, encourage the parties to reach a consensual settlement of the dispute.

§ 3 Judges, lawyers, public defenders and prosecutors must encourage the use of conciliation, mediation and other methods of consensual dispute resolution, even during the course of proceedings.

-

3 The Use of Online Dispute Resolution Platforms Inside and Outside Brazilian Courts

It should be noted that Brazilian Federal Rules of Civil Procedure establish that efficiency is a fundamental principle of Brazilian civil procedure.12xArt. 8. When applying the legal system, the judge is to pay heed to social purposes and meet the demands of the common good, safeguarding and promoting human dignity and observing the principles of proportionality, reasonableness, legality, publicity and efficiency. ODR is thus a means of promoting this fundamental principle, and the use of online dispute resolution platforms can be described as a game changer in the Brazilian civil justice system.

First, a very important platform is the one that is run on the website consumidor.gov.br. This platform is available to solve consumer disputes between consumers and businesses. Businesses need to be registered on the platform, in order to be claimed there.

This platform is designed only for negotiation between parties, but a result (a settlement or the impossibility of reaching one) is made available in an average of ten days. Further, the platform has an impressive rate of agreements in around 80% of the claims. Thus, we see that 8 of every 10 claims submitted to the platform are resolved without the participation of the Judiciary Power.

This success recently led to the celebration of an agreement between the Ministry of Justice and the National Council of Justice, in order to integrate the online platform to the courts.

Another important ODR experience is related to the insolvency proceeding of the largest Brazilian telecom company, Oi. Since it had a massive number of creditors, a platform, credor.oi.com.br, was created to enable settlements between the company and its creditors. During the first phase of the use of this platform, 37,152 creditors registered their credits, and 27,600 signed settlements. Thus, it has a rate of 74.29% of agreements.

In conclusion, ODR is changing when it is necessary to file a claim in the Judiciary Power, since the platforms can give a satisfactory answer to the claim fairly soon. As noted earlier, access to justice is the right to a fair resolution of a dispute. Therefore, when there is an adequate ODR platform to submit a dispute, interest in filing a lawsuit is filled only if the plaintiff tried to resolve the issue using ODR before going to court.

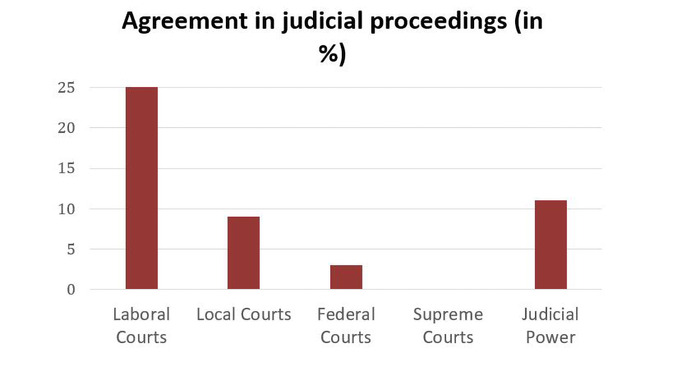

However, the Brazilian reality differs radically from that of North America, showing low success rates of agreement, at least in judicial proceedings. This is illustrated in the following graph:8xData collected from the mentioned Justice in Numbers 2018 Report (www.cnj.jus.br/files/conteudo/arquivo/2018/08/44b7368ec6f888b383f6c3de40c32167.pdf).

2.1 Technology as an Ally of Dispute Resolution

The last few decades have witnessed major technological advances, and the use of technology has been helpful to Law, especially dispute resolution, in which field a wide range of new mechanisms or rules in regard to technology have entered into force.

A few examples of technology-driven innovations are electronic proceedings, which do away with the need for paper; tools for analysing evidence; decisions dictated by algorithms; and online dispute resolution. There are projects that even aim to create a ‘robot judge’, to process cases and decide them, supervised by a human judge.9xEstonia is an example: “Estonia Is Building a ‘Robot Judge’ to Help Clear Legal Backlog”, available at: https://futurism.com/the-byte/estonia-robot-judge (last accessed 5 April 2019).

Electronic proceedings are a reality in a wide range of countries. For example, in Spain, Law 18/2011 regulated the use of technology of information in justice.10xFor an overview of the first developments of e-Justice in Europe and in the European Union, see A. de La Oliva Santos, F.G. Inchausti, & M.A. Morales (Coord.), La e-Justicia en la Unión Europea, Navarra, Editora Sarandi, 2012. In Brazil, Law n. 11.419/06 introduced the minimum rules governing electronic proceedings, specifically how parties are to be notified of claims and decisions.

Technology has also proved to be an ally in facilitating decision-making. Some software is fed in with algorithms to automatically submit a proposal of decision to judges, courts of appeal or Supreme Courts. The software uses data learning systems, and all the data submitted becomes instrumental in improving the accuracy of future decisions.11xDissertation on the multiple innovations brought by technology to judicial proceedings, J.N. Fenoll, Inteligencia artificial y proceso judicial, Madrid, Marcial Pons, 2018.

The focus of this article is online dispute resolution and its role in the Brazilian justice system.

Noten

-

1 https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/justice_scoreboard_2017_en.pdf.

-

2 www.cnj.jus.br/files/conteudo/arquivo/2018/08/44b7368ec6f888b383f6c3de40c32167.pdf.

-

3 To know more, see W. Ury, J.M. Brett, & S.B. Goldberg, Getting Disputes Resolved: Designing Systems to Cut the Costs of conflict, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1988.

-

4 F.E.A. Sander, ‘Varieties of Dispute Processing’, Federal Rules Decisions, Vol. 77, 1976, pp. 111-123.

-

5 Bringing a critical view of the role of agreements, O.M. Fiss, ‘Against Settlement’ (1984). Faculty Scholarship Series. 1215. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/1215.

-

6 The United States Department of Justice, ‘Alternative Dispute Resolution at the Department of Justice’, available at: https://www.justice.gov/olp/alternative-dispute-resolution-department-justice.

-

7 Brazilian Procedure Code: Art. 3. Neither injury nor threat to a right shall be precluded from judicial examination.

§ 1 Arbitration is allowed, in accordance with statutory law.

§ 2 The State must, whenever possible, encourage the parties to reach a consensual settlement of the dispute.

§ 3 Judges, lawyers, public defenders and prosecutors must encourage the use of conciliation, mediation and other methods of consensual dispute resolution, even during the course of proceedings.

-

8 Data collected from the mentioned Justice in Numbers 2018 Report (www.cnj.jus.br/files/conteudo/arquivo/2018/08/44b7368ec6f888b383f6c3de40c32167.pdf).

-

9 Estonia is an example: “Estonia Is Building a ‘Robot Judge’ to Help Clear Legal Backlog”, available at: https://futurism.com/the-byte/estonia-robot-judge (last accessed 5 April 2019).

-

10 For an overview of the first developments of e-Justice in Europe and in the European Union, see A. de La Oliva Santos, F.G. Inchausti, & M.A. Morales (Coord.), La e-Justicia en la Unión Europea, Navarra, Editora Sarandi, 2012.

-

11 Dissertation on the multiple innovations brought by technology to judicial proceedings, J.N. Fenoll, Inteligencia artificial y proceso judicial, Madrid, Marcial Pons, 2018.

-

12 Art. 8. When applying the legal system, the judge is to pay heed to social purposes and meet the demands of the common good, safeguarding and promoting human dignity and observing the principles of proportionality, reasonableness, legality, publicity and efficiency.