-

1 Introduction

‘Brain Waste’ is a term of art among refugee populations that refers to an all-too-common phenomenon involving the loss of credentials among those who have been forced to move from homelands to ‘safe’ havens in host countries.

A glaring example is the brain waste involving health-care professionals who are forced into refugee status. Doctors with well-established credentials and years of practice find themselves without credentials recognized by the host country, unable to find work in the fields in which they were trained. As one health professional observed, “The brain waste is appalling. These are individuals who could be taking care of children with asthma and instead are working at a car wash.”1x Dr. Jose Ramon Fernandez-Pena, in M. Nederman, ‘Why Refugee Doctors Become Taxi Drivers’, CNN Health, 9 August 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/08/09/health/refugee-doctors-medical-training/index.html (last accessed 8 July 2019).

But in one sense, these displaced doctors, nurses and health professionals are lucky. They have at least found a haven, they have new identities in their host countries that allow them to make a living doing something, and they are officially recognized by the host country as human beings.

For Syrian refugees in camps around the world, or for Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, or for any number of other refugee populations living in tents or makeshift shelters, isolated from local populations and largely unwelcomed by host countries, merely having professional credentials stripped away would seem a luxury. Refugees who land in the camps have generally lost all of the documentation that allowed them to claim a place in society – they have become, for all practical purposes, invisible.

One of the authors has experienced the effects of invisibility first-hand. In 2012, Toufic ‘Tey’ Al-Rjula discovered that he is, in fact, an ‘invisible man’. On his Dutch driver’s licence, you will not find a city name such as ‘Beirut’, ‘Damascus’, or ‘The Hague.’ Instead, his place of birth is declared as ‘Unknown’. This is because Tey was born in Kuwait to Syrian parents during the Gulf War, when the birth registries were destroyed en masse. Therefore, he does not have a birth certificate, and even if copies were to exist, neither he nor the issuing authority could possibly verify the document.

Two years later, in 2014, Tey started his asylum application in a refugee camp in the Netherlands, where he was forced to move when his work permit expired after five years. Then, for two years, he felt the pain of thousands of Syrian refugees unable to verify the authenticity of their documents. In addition, many of those refugees had lost other important documents, such as land titles and academic certificates. By the end of his stay, Tey had met more than a thousand invisible men, women and children. This experience, unfortunately typical of millions of refugees today, has driven the development of an identity programme that will be described later in this article.

Much of the work that has been done for refugees can be grouped under the umbrella of ‘Access to Justice’ (A2J). But A2J has traditionally been defined as access to the courts or formal justice systems. This is an approach to access to justice that provides, at best, tangential benefits for refugees. The World Justice Project has published the 2019 review of 126 countries, ranking them on an access-to-justice scale determined by an array of factors related to the independence and fairness of their court systems.2x World Justice Project, ‘Rule of Law Index 2019’ (last accessed 8 July 2019). But for even the most accessible justice systems in the world, one must exist – be a person recognized as having standing in that court’s area of control – in order to benefit.

A reconsideration of the basic elements of access to justice is needed. The authors would add at least three basic human rights to the list of things that should be elements of access to justice.The right to exist, to have an identity and to be recognized as a human being is a basic human right and an element of access to justice.

The right to control one’s identity, to decide who can access the elements of identity, under what conditions and for what uses is a basic human right and an element of access to justice.

The right to access opportunity and to unlock value in one’s knowledge and skills is a basic human right and an element of access to justice.

This white paper focuses on the need to develop an alternative approach to the concept of access to justice, and calls for a coordinated attempt to create standards for identity construction, reconstruction and control. A guiding fact is that, to an ever-increasing degree, identity around the world is being created, stored and used digitally.

This white paper does not seek to establish standards for creation or re-creation of identities. That is a complicated, iterative process that will stretch over time and benefit from contributions by many organizations. But there are some related questions that this white paper does aim to address.

First, what is the history and context of the ‘refugee crisis,’ and what has been done in the past to address the destruction of identities among refugees? There is no ‘justice layer’ of the Internet – that is, there is no legal environment that stretches across boundaries and furnishes rules and structures agreed on and followed by the myriad of state actors who deal with refugees. But there is some precedent for the creation of solid identities, voluntarily accepted across national borders, that may give some guidance to the creation of standards that would bring refugees out of invisibility. The opening section of this article deals with this history and the transnational nature of standards-driven approaches to identity.

Second, what is the current state of digital identity creation around the world? Many projects are underway that use various digital formats and archiving platforms to create online identities, but most of them are state-bound. That is, they are designed to operate within the boundaries of a political entity, and they are generally designed to establish citizenship and access to social benefits that are largely denied to refugees. The second section of this article reviews the current state of digital identity creation.

Third, what are some examples of current digital ID projects that do not rely on state authorization or national boundaries? Although there are no internationally recognized standards for creating or re-creating identities, there are examples of process-driven projects that can show the way towards larger, more generalizable, approaches to digital IDs. The third section of this article will offer some examples.

Finally, what is a generalizable framework for digital ID projects, and what issues must be considered when developing standards that can be formalized and recognized internationally? Each refugee situation will be to some extent unique, but there are some process models that can be used as a framework for standards development. The fourth and final section of this article explores one such model.

It is hoped that the discussion surrounding these basic questions will prompt cooperative work among international organizations concerned with refugees, standards and technology, and that the cloak of invisibility over refugee populations can be lifted. -

2 History and Context

There is a growing need to find practicable ways for refugees to help themselves. Overcoming the impasse of refugees stuck between a country they were forced to leave and a country that has unenthusiastically become their current refuge has been frustrating for all concerned.

Refugees are reluctant travellers. They have been forced out of their homes and seek temporary alternatives that will offer them shelter, food and safety. Sovereign states, in turn, are reluctant hosts. They did not ask for refugees to land on their shores, and they worry about how to shelter and feed refugees, preserve security and avoid confrontation. International non-governmental organizations find themselves caught between an obligation to fulfil the basic needs of refugees and the sovereign concerns of the nation-states. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) defers to the wishes of host countries, yet the UN 1951 Refugee Convention, relating to the status of Refugees (1951 Convention), gives international standing to the plight of refugees.3x UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, Art. 1(A)(2), 28 July 1951 (189 UNTS 137). “Owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.” The result has been a series of halfway measures that frustrate both camps.

It may be helpful to isolate particular issues – what are called ‘wicked problems’4x A ‘wicked problem’ is one that is highly difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete, contradictory and changing requirements that are often difficult to recognize. Wicked problems are usually ones that do not have a ‘true-false’ axis, but fall upon a ‘better or worse’ continuum. Such problems are often economic, political or environmental issues, and involved stakeholders often have radically different world views. Often political ‘solutions’ to wicked problems can stress those who have standing in the issue, which induces policymakers to kick the can further down the road. – and look to third-party organizations such as the international standards community to help craft practicable solutions to issues that currently overwhelm refugees and host countries. In particular, addressing issues dealing with defining a constructive role for refugees to play while living inside a host country would mitigate much of the angst that refugee status currently entails. Standards organizations, such as ISO (the International Organization for Standardization), already play an important role in refugee camps by defining such things as design specifications for camp structures, community building resilience, record management, hospital and food safety standards, product designs of relief supplies, systems engineering standards and specially designed cookstoves.5x M. Lazarte, ‘ISO Focus Magazine’, 19 September 2017, www.iso.org/news/ref2222.html.

The world has always had refugees,6x The plight of refugees is a classic concept in human lore; from Adam and Eve forced to leave Eden to Oedipus and Odysseus wandering the old world, refugees have long been strangers in strange lands. but issues involving refugees have gotten worse, not better, in the twenty-first century. There is a growing concern in developed Western nations that the current diaspora of refugees from the Middle East and Africa to Europe, and/or migration from Mexico and Central America to the United States, has become an insoluble public policy issue.7x This was not always the case. In the 1776 Declaration of Independence describing King George III’s “repeated injuries and usurpations on American rights and liberties,” the Founding Fathers complained that the King “has endeavored to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither ….” (The Plantation Act of 1740 allowed any Protestant alien residing seven years in one of the American colonies to have the same rights as one of “his Majesty’s natural-born subjects”). Are developed nations at risk by what seems an unprecedented movement of refugees from their countries of origin to countries of destination, where they are both unknown and uninvited?

As Emma Haddad points out,As long as there are political borders constructing separate states and creating clear definitions of insiders and outsiders, there will be refugees. Such individuals do not fit into the state-citizen-territory hierarchy, but are forced instead into gaps between states.8x E. Haddad, The Refugee in International Society, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 7. “States can be differentiated from other forms of belonging by their attachment to sovereignty, borders and territory. Refugees therefore pose a problem for the international community quite different from other foreigners.”

The United States serves as a case in point. The current debate over refugees from Mexico and Central America is couched by some as ‘an invasion’ that brings drugs, criminals and families desiring to go on welfare. Others accept the analysis of organizations such as the Cato Institute, which reports that refugees and migrants

… 1) increase the productive possibility of the US economy and currently account for 11 percent of all economic output; 2) are twice as likely to start a new business as native-born Americans; and 3) basic indicators of assimilation from naturalization to English ability, are if anything, stronger now than they were a century ago.9x A. Nowrasteh, ‘Myths and Facts of Immigration Policy’, Cato Policy Report, Jan/Feb 2019, Vol. XLI, No. 1.

Prior to the expansion of violence in the twentieth century, being a refugee was a temporary position before a new home was found. Irish Catholics and Russian Jews (among others) looked across the Atlantic. Chinese sought new homes in the Indies, Singapore and San Francisco. In the Balkans, Greeks came home from Turkey and Bulgaria. Nineteenth century migrations were usually country-specific and of short duration. Refugees knew where they wanted to migrate to, and while many states welcomed refugees, other states countered migration desires by passing restrictive laws to limit the influx of refugees.

This situation was changed for the worse by World War I, the war that was expected to end all wars. The length and severity of the war was unexpected, and when the victors arrived at Versailles they were committed to breaking up the old empires of Germany, Austria-Hungry and Turkey – Russia fell apart on its own. The aspirational goal of the victors at Versailles for national sovereignty for the new nation-states quickly turned sour as lines drawn on maps captured unwilling minorities behind borders as well as ‘liberating’ supposed majority populations. In a chapter entitled “The Decline of the Nation-State and the End of the Rights of Man”, Hanna Arendt describes the clash of tribe versus tribe in the twilight following the war that was to end all wars.10x H. Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, New York, 1976, p. 267. “Civil wars that ushered in and spread over the twenty years of uneasy peace were not only bloodier and more cruel than all their predecessors; they were followed by migrations of groups who, unlike their happier predecessors in the religious wars, were welcomed nowhere and could be assimilated nowhere. Once they had left their homeland they remained homeless, once they had left their state they became stateless; once they became deprived of their human rights they were righties, the scum of the earth.”

The creation of the many new nations in Central Europe and the Middle East caused a huge diaspora of refugees who were forced to leave homelands and find refuge elsewhere. Greeks and Turks by the millions exchanged places. A quarter of a million Bulgars returned to Bulgaria, two million Poles and a million Germans were forced to migrate. This was a slow-moving crisis, and by 1926 there were still 9.5 million refugees in camps and dispersed into urban environments. White Russians, Mensheviks, socialists and liberals all had to abandon Russia for boltholes in locations ranging from Paris to Tashkent to Shanghai. Poles and Russians waged a brutal border war. Greeks moved west, the Turks east and the few Armenians followed the Jews into fragile places of exile.11x See T. Zahra, The Great Departure – Mass Migration and the Making of the Free World, New York, WW Norton, 2016.Outside Athens, on the Piraeus, in Salonika, masses of humanity lay rotting in the cold of a Greek winter. Then the Fourth Assembly of the League of Nations, in session in Geneva, voted one hundred thousand gold francs to the Nansen relief organization for immediate use in Greece. The work of salvage began. Huge refugee settlements were organized. Food was brought and clothing and medical supplies. The epidemics were stopped. The survivors began to sort themselves into new communities. For the first time in history, large scale disaster had been halted by goodwill and reason. It seemed as if the human animal were at last discovering a conscience, as if it were at last becoming aware of its humanity.12x E. Ambler, A Coffin for Dimitrios, London, Vintage Crime, 939, pp. 51-52.

The newly formed League of Nations felt obligated to act as the lead authority to deal with the problem, in large part because of the inability (and unwillingness) of the nation-states to deal with the unintended consequences of the Treaties of Versailles. The League’s High Commissioner for Refugees, Fridtjof Nansen, found quickly that the League could promise but rarely deliver; and he was forced into dependence on private sector organizations such as the International Red Cross and the American Relief Organization, led by Herbert Hoover, to deal with immediate needs for shelter, food and security.13x M. Marrus, The Unwanted; European Refugees in the Twentieth Century, New York, Oxford University Press, 1985, p. 88. “Establishing a pattern that would become familiar in the interwar period, Nansen drew upon the League of Nations only for its prestige and administrative assistance; the actual operation was supported by private agencies.” Nansen acknowledged his dependency on private sector organizations through the creation of an Intergovernmental Advisory Commission for Refugees, “a body that acted under the auspices of the League of Nations, but which included both state officials and representatives of private organizations”.14x Haddad, 2008, p. 112.

Nansen quickly realized that a key tool was missing to aid refugees: internationally recognized identification papers. This was a huge impediment to their request for safe asylum, and left them not only ‘stateless’ but invisible, as they lacked the ability to prove who they were. The resultant ‘Nansen Passport’ was created to give refugees what food and shelter could not: an instrument that gave a refugee a sense of belonging and stability in a world that had spun out of control, leaving refugees “suspended in a web of international legal technicalities”.15x Marrus, 1985, p. 111. “All this was achieved with a very small staff working closely with private and voluntary agencies… To help coordinate the work of these agencies, a Permanent International Conference of Private Organizations for the Protection of Migrants assembled in Geneva in 1924.”

The Nansen Passport was a document that had no official standing, but it was accepted by most countries as a way to attest to the bona fides of the refugee and recognized the de facto acceptance of refugees carrying the document. Only sovereign states can decide who can legally cross their borders, and while some nation-states refused to recognize the Passport, the League of Nations mandate gave needed credibility to the understanding that refugees were citizens of the world, even if not citizens of an individual nation-state. Russian refugees made the observation, “Man consists of a body, a soul and a passport.”16x E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, G. Loescher, K. Long & N. Sigona (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Forced Migration Studies, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2014, and K. Jacobsen, Livelihoods and Forced Migration, p. 105: “Official documents are [often], poorly designed – often handwritten and illegible – or flimsy and easily destroyed – and they do not look legitimate. Documentation must be recognized by authorities, and authorities trained to act according to the rights conferred, in order to provide effective protection”.

As with the post-World War I refugee crisis, the post-World War II era began with a concern by the sovereign states that the refugee crisis would wash up on their shores never to leave. This sense of alienation on the part of refugees and the commensurate sense of imposition on the part of the nation-states has defined the modern impasse of the refugee dilemma. Just as today we have refugees from Syria, minority Sunnis in Shiite territory, Kurds without a national base and Africans trying to leave chronic warfare, corruption and poverty behind, after World War II millions of displaced persons (DPs) moved from East to West, and to a lesser extent from West to East, because staying where they were at the end of the war was not a viable option.

For six years, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) worked closely with private organizations such as the Red Cross and the American Friends Society to bring order to these camps of DPs. In the beginning there was only chaos. In the words of one UNRRA administrator, “There was tremendous disorder. It was a shambles … sullen inmates … choked toilets … and the threat of typhus.”17x M. Wyman, DP: Europe’s Displaced Persons (1945-1951), Philadelphia, The Balch Institute Press, 1998, pp. 38-39.An early key decision made by the understaffed UNRRA officials was to devolve as many governance obligations as was possible on the refugees themselves. UNRRA stressed camp democracy on ideological grounds … and because experience showed it was the best plan in such conditions. Soon the camps were being run largely by elected camp committees and in many cases UNRRA leaders were only nominally in charge.18x Ibid., p. 117.

Because refugee camps were removed from the economic and cultural life of the host country, the refugees had to develop their own educational systems outside of the traditional schools of the host state. These schools were informal and depended entirely on the skills of the refugees themselves, with minimal funding from UNRRA. At the highest level, ‘universities’ were set up that required exams and academic records for acceptance. Getting such valuable documentation from students who had been on the move for many years was not always possible, so ad hoc exams were utilized to enable students to attest to the level and quality of their education.

Many refugees from eastern Europe soon realized that they were not going to be able to return home, where the Soviet Union now dominated the politics and culture of the entire region.Gradually, [the UNRRA] operations slipped into a dull routine of care and maintenance, the spirit of which was reflected in the dreary, mournful appearance of the refugee camps and centers that dotted Central Europe a year and a half after the war was over.19x Marrus, 1985, p. 324.

In December 1946, UNRRA transferred all its obligations to a new UN agency, the International Refugee Organization (IRO), which was given more authority to work collaboratively with refugees to resolve concerns as to what was to be their ultimate fate.

Unlike UNRRA, which worked constantly at the end of a tight leash, IRO had its own resources and could negotiate agreements … with the military occupational authorities and with governments.20x Ibid., p. 343.

The IRO quickened the tempo of resettlement21x Between mid-1947 and the end of 1951, the IRO resettled just over one million refugees into new homes in new countries of destination. Ibid., p. 344. and “attempted to link the economic needs of various countries with particular skills among the DP population”.22x Ibid., p. 344.

The IRO, working collaboratively with the refugees themselves, found a path forward for those who had felt unwanted and invisible. Refugees created educational opportunities and developed or renewed occupational skills. They came to feel that their life would finally move forward again. It was going to be up to them to take what they thought they had irrevocably lost and integrate it into a new life.If the authentic literature of the Croatian past , for example, was to be saved, it must be done by the DPs. If the Latvian language was to retain its purity and beauty before being Russified, it must be through the lips of the DPs.

In the refugee camps “were a people in exile who still yearned for the tales, songs and prayers of their native land”. Refugees were convinced that, while in exile, they still represented the heart and soul of their native country. “They were now the sovereign nation.”23x Wyman, 1998, p. 157. (Emphasis added).

The refugee crisis of the twenty-first century has become global. The refugees themselves are from a wider scope: the Middle East and North Africa as well as south of the Sahara and from the Horn of Africa, East Asia and Central America. While refugee protection has become a global public responsibility under the 1951 Convention, nation-states have strong incentives to free-ride on the contributions of other nation-states who are either more responsible in meeting global obligations or luckier in being further away from the problem.24x A. Betts, ‘International Relations and Forced Migration’, in E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, G. Loescher, K. Long & N. Sigona (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 66.

In the Middle East, the destruction wrought by nation-states and their theocratic adversaries has shattered communities and traditional political loyalties. It has also badly wounded a nascent civil society that had been the hope for the future in the Middle East. The Arab Spring had released a longing by young people – and others – for a world not dominated by theocratic institutions or the off-again, on-again brutality of autocratic nation-states. In Tunisia – which called forth the Arab Spring – four members of Tunisian civil society were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their work in developing a countervailing governance approach that depended on the energy of the students, the pragmatism of shopkeepers, and the working poor to create a new demos. The nation-states of the Middle East have returned to bad, old habits, and it is the civil society leaders who currently carry the tenuous hopes of the region. As stated in the Peace Prize announcement, this civil society Quartet filled the governance void in Tunisia:[W]hen the democratization process was in danger of collapsing as a result of political assassinations and widespread social unrest. It established an alternative, peaceful political process at a time when the country was on the brink of civil war. It was thus instrumental in enabling Tunisia, in the space of a few years, to establish a constitutional system of government, guaranteeing fundamental rights for the entire population, irrespective of gender, political conviction or religious belief.25x The 2015 Nobel Peace Prize: “The National Dialogue Quartet” for their “decisive contribution to the building of a pluralistic democracy in Tunisia in the wake of the Jasmine Revolution of 2011.” Oslo, 10 October 2015.

The inability (to date) of the Arab Spring to become a countervailing political force in the Middle East has in part led to the third mass migration of refugees of the past century. What lessons can we learn from the first two refugee crises that followed the World Wars? Unfortunately, the refugee issue most often turns into an us-against-them dichotomy that makes the search for consensus solutions difficult. In the middle, with few resources and few allies, are the functional international organizations (such as the League of Nations and UNHCR). The time has come to expand the discussion and open up the playing field to other groups who have issues involved but who have been to date ineffectual in stating their standing and pressing for their involvement. One step that needs to be taken is to recognize that ‘us and them’ does not just mean refugees and the host country nation-states. As a scholar of refugee studies points out:

Far from being a ‘statist’ mode of governance, as it is often portrayed, the governance of forced migration now involves a range of non-state actors, including armed actors, NGOs, transnational civil society, and increasingly the private sector …. However, this role has rarely been recognized or studied in relation to forced migration.26x Betts, 2014, p. 69.

In light of the changing, indeed worsening refugee situation, and in light of the shortcomings of state-based solutions to refugee invisibility, what identity approaches have worked in the past, and what can work in the future?

Running parallel to the top-down authority of the nation-states, over the past century there has been the development of a countervailing authority for global governance utilizing the political and economic power, the expertise and the gravitas of civil society and business. In a global world, the nation-states have been unable in many cases to supply the public goods of global governance needed to effectively run the global marketplace and supply consensus solutions for the wicked problems that an integrated world requires.

For example, because of the rigour of the private sector, consensus-based standards process, the World Trade Organization (WTO) looks to internationally recognized standards bodies to verify the bona fides of products in global trade. The nation-states have been known to claim that imported products fail to meet domestic health and safety rules in order to keep out foreign competition. Such national rulings are considered ‘technical barriers to trade’.27x WTO, TBT, 15.4: “The Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) Agreement aims to ensure that technical regulations, standards, and conformity assessment procedures are non-discriminatory and do not create unnecessary obstacles to trade.” To help ensure that the nation-states cannot ‘game’ the world trade system through trumped up health and safety assertions, products that conform to the standards of internationally recognized standards bodies are considered to meet WTO requirements and cannot be denied entry. Thus, private sector standards have ‘standing’ at the WTO; standards created by legislatures or various government regulatory bodies in the nation-states are denied similar standing.28x World Trade Organization, Technical Barriers to Trade: Technical Explanation (Harmonization and the TBT Agreement), 16 December 2013. “For many years, technical experts have worked towards the international harmonization of standards. An important role in these efforts is played by the International Standardization Organization (ISO), the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Their activities have had major impact on trade, especially in industrial products. For example, ISO has developed more than 9,600 international standards covering almost all technical fields.” The European Community, the United States and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have all urged that their regulatory bodies “refer to international voluntary standards, specifications and test methods rather than produce their own”.29x C. Murphy & J. Yates, The International Organization for Standards (ISO), New York, Routledge, 2009, p. 44.

Among the first such international management standards – and ultimately the global standard with the most extensive use – is ISO 9000 on quality assurance systems. ISO 9000 is a process (and an exacting one) of the management criteria required in the global marketplace to ensure that customer expectations of product quality, price and distribution are met. Most current uses of ISO 9000 are by manufacturers supplying products and services into global supply chains. This is in large part due to the interest of potential exporters in East Asia, Eastern Europe and elsewhere to overcome ‘information asymmetries,’ i.e. that buyers have no knowledge as to the bona fides of autonomous exporters and so are looking for ways to assess the product quality and reliability of an unknown supplier. An accredited third-party audit of the suppliers’ management systems under an IS0 9000 certification process can act as a viable ‘quality signal’ to a potential global purchaser that an unknown supplier is incapable of offering directly.

The dramatically successful uptake of the ISO 9000 quality assurance process was largely due to a growing awareness by businesses and governments of the benefits that a trusted (i.e. accredited) and widely accepted global standard could offer to participants in the global marketplace. Authoritative non-governmental organizations such as ISO are increasingly seen by public international organizations as appropriate venues for the resolution of global supply chain problems, the certification of trusted processes and the creation of needed global public goods.

As an example, in the early 1990s a number of national initiatives on environmental issues began to create mixed political signals with the proliferation of potentially conflicting national and regional environmental standards on such issues as environmental management, life cycle assessment, sustainability, green labelling and disclosure. Not only did the lack of global harmonization result in a waste of environmental resources and muddled mitigation efforts, but it also created perverse incentives. WTO rules target countries, not companies, allowing environmentally reputable companies to suffer the same fate as ‘bad actors’ when country-specific trade penalties were assessed. ISO standards are both global and company-specific; the existence of national boundaries are irrelevant to the success (or failure) of meeting ISO management standards requirements.

The final incentive for ISO to move forward on developing an environmental management standard was the run-up to the June 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, where the conference leadership specifically asked the ISO Central Secretariat to make a commitment to creating a global environmental standard. The resulting management system, ISO 14000, covers five separate environmental concerns: a baseline management system, auditing, green labelling, environmental performance evaluation and life cycle assessment. As with ISO 9000 management system requirements, meeting what is now the ISO 14000 suite of environmental standards has become a prerequisite for many manufacturers and other organizations that wish to participate in the global marketplace.

Certifying global standards such as ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 thus addresses difficult sovereign-state governance issues. When there are questions aboutthe overall reputation of the country in which the seller is located … ISO certification can act as a stronger signal of performance in contexts with corrupt or otherwise weak regulatory institutions.30x D. Berliner & A. Prakash, ‘Public Authority and Private Rules’, International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 58, No. 4, 2014 (1-11), p. 3. “Thus, exporting firms located in countries with reputations for environmental problems or low product quality can face a ‘market for lemons’ problem and suffer a competitive disadvantage in the international market. In such a context, sellers can use quality or environmental certifications to rebrand themselves and signal their commitment to high product quality and environmental stewardship to their foreign buyers.”

The widespread global take-up and acceptance of these two global management standards is a clear sign that a) practicable global governance solutions can develop outside of the nation-state environment and b) consensus governance solutions that induce good behaviour can often be more viable than top-down attempts by the nation-states to prohibit bad behaviour.

More recent efforts to create new global management standards, ISO 45000 on worker safety in global supply chains and ISO 37000 on anti-bribery and anti-corruption efforts, have both been developed and ratified by ISO in the past few years. These global management standards are good examples of creating practicable solutions to those ‘wicked problems’ that have confounded the best (and worst) efforts by the nation-states to respond.ISO has actually begun to become an alternative to our ineffective UN system of intergovernmental organization, a development that some observers of voluntary consensus standard setting have championed for almost a century.31x Murphy & Yates, 2009, p. 68.

Practicable global solutions require the work of many. Ensuring business and civil society are involved from the beginning of a solution-seeking process will almost certainly lead to better solutions and consensus support. Laws made by nation-states place all their political capital into the crafting of legislation. Once created, a ‘law’ is considered the final word, and lawmakers walk away. With standards creation, the consensus process requires that all affected parties participate. Unlike a law, a standard is expected to be dynamic and thus subject to continuous review.32x ISO standards must be reviewed at least every five years, and most sooner than that. Standards creation should be considered a process of continuous, significant, incremental improvements. Thus, the politics of law creation creates an artificial endpoint. Standards creation and implementation are never considered concluded.

Hundreds of new standards are needed each year (to reflect new products and new services), and each standard needs to be updated constantly. As a result, when legislatures do set industrial standards, they have a tendency to leave them in place for decades or even generations, and inflexible, unamendable standards really can stifle innovation.33x Murphy & Yates, 2009, p. 9.

The ISO Committee on Developing Country Matters (DEVCO) held a meeting in late 2017 on Missing Persons and Refugees, ‘A new target for standardization?’, as part of the 2017 ISO General Assembly. The keynote speaker, Prof. Jurg Kesselring, Chair of the International Red Cross MoveAbility Board, stated: “When a product, activity or service meets ISO standards, there is a general expectation that it will be delivering what is expected of it.” At the same meeting, a spokesperson from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Lebanon pointed out that 84% of the world’s refugees are hosted in developing countries.

Standardization is a way of putting in place practical solutions that are reproducible and harmonized, which could help host countries in their response to many of the issues they face while helping refugees.34x “Missing Persons and Refugees – a new target for standardization?”, FOCUS Magazine, 19 September 2017.

-

3 The Current Status of State-Based Digital ID Projects

Later in this article some examples of non-state identity programmes using information and communication technology will be offered. But a survey of digital identity programmes from around the world reveals that many, if not most, attempts to use technology to establish identity are state-based. These state-based programmes exhibit many of the strengths and weaknesses of digital identity programmes generally, but they are, almost universally, not available to or of help to refugee populations.

Modern national identification is believed to have begun under Napoleon in the early 1800s, as the ruler was attempting to consolidate his governance of France.35x C. Jerzak, ‘A Brief History of National ID Cards’, Harvard Univ. FXB Center for Health & Human Rights, 12 November 2015, https://fxb.harvard.edu/2015/11/12/a-brief-history-of-national-id-cards/ (last accessed 4 April 2019). Other countries tried other national identification schemes after that, most notably the Ottoman Empire in the late 1800s.36x Ibid. National identification became common during World War II, first with adoption in Europe and with the creation of national identification papers in England, Germany, France and other countries.37x Ibid.

A more recent surge in national identification schemes began, following the events of 9/11.38x ‘The History of Federal Requirements for State Issued Driver’s Licenses and Identification Cards’ (National Conf. of State Legislatures), www.ncsl.org/research/transportation/history-behind-the-real-id-act.aspx (last accessed 4 April 2019). In 2005, the US Congress passed the Real ID Act39x The Real ID Act of 2005, Pub. L. 109-13, 119 Stat. 131, Division B, Title II (11 May 2005), codified at 8 U.S.C. §§ 101, et seq. to assure the consistency and reliability of the US states’ driver’s licences as identification. Driver’s licences are the principal form of identification in the United States and are widely used for airline travel, banking and other financial transactions and proof of age.

Shortly thereafter, the European Union took steps towards ensuring interoperability among digital identification beyond the borders of a singular nation. In 2011, the EU parliament adopted a regulation on digital identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market,40x EP Reg. of 23 July 2014, OJ 910/2014 L 257/73. which is commonly referred to as the eIDAS Regulation (Electronic Identification and Trust Services Regulation). The regulation requires that by 29 September 2018:[w]hen an electronic identification using an electronic identification means and authentication is required under national law or by administrative practice to access a service provided by a public sector body online in one Member State, the electronic identification means issued in another Member State shall be recognised in the first Member State for the purposes of cross-border authentication for that service online …41x Ibid., Art. II, Chapter 6.

European Union member countries that have developed and rolled out digital identification cards under eIDAS include Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Malta, Netherlands, Spain and Turkey.42x M. Eichholtzer, ‘Overview of pre-notified and notified eID schemes under eIDAS’ (2 January 2019), https://ec.europa.eu/cefdigital/wiki/display/EIDCOMMUNITY/Overview+of+pre-notified+and+notified+eID+schemes+under+eIDAS (last accessed 4 April 2019). Some of the identification cards are simply travel cards that can be used in the EU, such as the passport card issued by Ireland.43x ‘Passport Card’ (Dept. of Foreign Affairs and Trade), www.dfa.ie/passportcard/ (last accessed 12 April 2019). Other identification cards permit the holders to access a range of services from the government as well as from banks, including those issued by Croatia,44x ‘Overview of the Croatian eID Scheme’ (Ministry of Public Administration, 27 June 2018), https://ec.europa.eu/cefdigital/wiki/display/EIDCOMMUNITY/Croatia?preview=/62885743/65972541/G1.v4.0%20_%20Overview%20of%20the%20Croatian%20eID%20scheme.pdf (last accessed 8 April 2019). Estonia,45x ‘ID-Card – e-Estonia’, https://e-estonia.com/solutions/e-identity/id-card/ (last accessed 8 April 2019). Finland,46x ‘Use of the Identity Card’, www.poliisi.fi/identity_card/use_of_the_identity_card (last accessed 8 April 2019). Germany47x ‘German National Identity Card – The Electronic Functions’, www.personalausweisportal.de/EN/Citizens/German_ID_Card/Functions/Functions_node.html (last accessed 8 April 2019). and Italy.48x ‘The New Italian National EID Card Goes Live (2018 Update)’, 7 March 2019, www.gemalto.com/govt/customer-cases/new-national-identity-card-for-italy (last accessed 8 April 2019).

Estonia’s national identification card has multiple uses in accessing government and private services, such as health services, medical and prescription records, banking services, voter identification and tax information. In addition, the Estonian identification can be loaded on an app on a mobile phone.49x Supra, n. 45.

Each EU country-issuer sets its own standards for what documentation is required for a holder to obtain a digital ID and what biometrics or other personally identifying information will be imprinted as a part of the ID. For example, some EU countries embed one or more fingerprints or facial recognition metrics into the chip on the card. Germany permits ID holders to include two fingerprints on the card chip at the holder’s option,50x Supra, n. 47. Croatia includes two fingerprints on the card chip,51x Supra, n. 45, p. 9. while Turkey includes all 10 fingerprints as well as palm prints.52x ‘Distribution of Biometric Turkish ID Cards Begins’, Hürriyet Daily News, 23 March 2016, www.hurriyetdailynews.com/distribution-of-biometric-turkish-id-cards-begins-96822 (last accessed 15 April 2019).

Electronic identification within the EU, however, is not universally accepted by its member states. Notably, the United Kingdom has not yet created a widely accepted digital identification, although it has passed laws and regulations from time to time, planning such rollouts. The Identity Cards Act 200653x O. Dowden, ‘GOV.UK Verify programme’, HC Deb 9 Oct 2018 978WS. was the first attempt to adopt a national digital identification card that would connect to a database containing the biometric information of the cardholders. The Identity Cards Act of 2006 was repealed in 2010 owing to concerns regarding the large databases holding the biometric data, as well as the cost of rolling out the programme.54x A. Travis, ‘ID Cards Scheme to Be Scrapped within 100 Days’, The Guardian, London, 27 May 2010, www.theguardian.com/politics/2010/may/27/theresa-may-scrapping-id-cards (last accessed 16 April 2019). The databases were to be destroyed, and all cards issued under the programme were declared invalid.55x ‘Identity Cards and New Identity and Passport Service Suppliers’, 26 March 2013, www.gov.uk/guidance/identity-cards-and-new-identity-and-passport-service-suppliers (last accessed 28 March 2019).

Following the lead of the European Union, several regional trade groups have enacted various regulations, agreements and treaties to enable relatively free travel between the member countries using a national digital ID card in lieu of a passport.56x M. Czaika, H. de Haas & M. Villares-Varela, ‘The Global Evolution of Travel Visa Regimes’, Population & Development Rev., Vol. 44, 2018, p. 589, doi:10.1111/padr.12166.

The member countries of the South American trade consortium Mercado Común del Sur (MERCOSUR)57x The member states of the MERCOSUR are Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. Although formally a member, Venezuela’s membership is currently suspended. Bolivia is in the process of becoming a member. Associate states of MERCOSUR are Chile, Columbia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru and Surinam. ‘MERCOSUR Countries’ (MERCOSUR), www.mercosur.int/en/about-mercosur/mercosur-countries/ (last accessed 12 April 2019). recognize digital identification of other countries in the group in lieu of a passport.58x ‘XLVIII Summit of Heads of State of MERCOSUR and Associated States’, 17 July 2015, www.itamaraty.gov.br/images/documents/Documentos/Fact_Sheet_Mercosur_English.pdf (last accessed 11 April 2019).

Also in a manner similar to that of the European Union, the Economic Community of Western African States (ECOWAS)59x The countries in the ECOWAS are Benin, Burkina Faso, Capo Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo, www.bidc-ebid.org/english/ (last accessed 12 April 2019). has created a scheme whereby citizens within the ECOWAS can travel freely to other member countries using digital national ID.60x S. Atkins, ‘Turning the ECOWAS ID Card from Vision to Reality’, The Silicon Trust, 13 April 2018, https://silicontrust.org/2018/04/13/turning-the-ecowas-id-card-from-vision-to-reality/ (last accessed 12 April 2019). The first country in the ECOWAS to issue a digital ID under the ECOWAS scheme was Senegal.61x A. Perala, ‘Senegal First ECOWAS Member to Begin Issuance of Biometric IDs’, FindBiometrics, 7 October 2016, https://findbiometrics.com/senegal-biometric-id-310071/ (last accessed 12 April 2019).

The national identification card issued by Nigeria has practical day-to-day applications. In addition to being used as identification to access government services and for travel without a passport to several other member countries of the ECOWAS62x Ibid. the card can also be used as a payment device through MasterCard.63x ‘About the e-ID Card’, National Identity Management Commission, www.nimc.gov.ng/the-e-id-card/ (last accessed 9 April 2019). The Nigeria ID card stores all 10 fingerprints on a chip on the card.64x ‘Nigerian National ID Program: An Ambitious Initiative’, Gemalto, 7 March 2019, www.gemalto.com/govt/customer-cases/nigeria-eid (last accessed 12 April 2019).

Ghana has also created a national identity card that can be used for travel in the ECOWAS.65x ‘FAQs on the Ghana Card and Related Matters, National Identification Authority, www.nia.gov.gh/faq.html (last accessed 12 April 2019). The Ghana ID card has both a physically readable chip and a Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) chip and contains the user’s fingerprints.

More recent developments in national identification systems are the usage of biometrics, exploiting the individuality of physical characteristics of fingerprints, iris, face, veins and other body parts.

India leads the field in biometric identification, with its national digital identification card known as the Aadhaar card.66x ‘What Is Aadhaar’, Unique Identification Authority of India, https://uidai.gov.in/what-is-aadhaar.html (last accessed 8 April 2019). The Aadhaar database is believed to be the largest biometric database in the world, with over one billion users.67x ‘India’, Electronic Frontier Foundation, 4 May 2018, https://www.eff.org/issues/national-ids/india (last accessed 28 March 2019). The card is on paper, with a two-dimensional barcode known as a quick response (QR) code that contains some of the demographics of the cardholder and a digitized photo in addition to having a digital key giving the reading device access to more of the ID holder’s demographics and biometric data contained on a central database.68x ‘Updated QR Code to Shield Aadhaar Information’, The Times of India, 19 April 2018, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/updated-qr-code-to-shield-aadhaar-info/articleshow/63823001.cms (last accessed 16 April 2019). Holders can download and print their own card from any computer and printer.69x P. Motiani, ‘How to Get Duplicate Aadhaar Online If You Have Lost Yours’, Economic Times, 23 November 2018, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/wealth/personal-finance-news/lost-your-aadhaar-heres-how-to-get-a-duplicate-aadhaar-online/articleshow/59466455.cms (last accessed 8 April 2019). In addition, the Aadhaar card can be accessed using an Android smartphone.70x ‘mAadhaar FAQs’, Unique Identification Authority of India, https://uidai.gov.in/contact-support/have-any-question/285-faqs/your-aadhaar/maadhaar-faqs.html (last accessed 9 April 2019). The biometrics database for each cardholder contains 10 fingerprints, iris scans of both eyes and digital facial recognition, making it the most exacting of all government-issued digital identification schemes.71x ‘Aadhaar Features, Eligibility’, Unique Identification Authority of India, https://uidai.gov.in/contact-support/have-any-question/286-faqs/your-aadhaar/aadhaar-features,-eligibility.html (last accessed 9 April 2019).

The concentration of personal biographic, demographic and biometric data of the holders of the Aadhaar card is controversial within India.72x S. Shukla, ‘Aadhaar Verdict: Why Privacy Still Remains a Central Challenge’, The Economic Times, Mumbai, 27 September 2018, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/aadhaar-verdict-why-privacy-still-remains-a-central-challenge/articleshow/65970934.cms?from=mdr (last accessed 16 April 2019). The constitutionality of the Aadhaar programme as well as the question of whether the Indian Constitution contains a fundamental right to privacy was argued before the Supreme Court of India.73x Puttaswamy v. Union of India, (2017) 10 Scale 1. In a unanimous decision, a nine-judge panel held that the Indian Constitution does contain a fundamental right to privacy and that certain aspects of the Aadhaar scheme violated that right, particularly the ability of non-governmental, commercial entities to access the Aadhaar database in order to confirm the identity of an Aadhaar cardholder.74x Ibid.

Israeli law requires that all Israeli citizens carry the national identification card, the ‘Tehudat Zehut’.75x ‘Apply for an ID’, Population and Immigration Authority, www.gov.il/en/service/biometric_smart_id_request (last accessed 9 April 2019). The card has a machine-readable chip that contains digital facial recognition and the prints of two fingers.76x Ibid.

Saudi Arabia’s digital identification is required to be carried by all of its citizens and expatriates in the country.77x ‘Deadline for Enrollment in Saudi Arabia Biometric Registry Looms’, FindBiometrics, 19 January 2015, https://findbiometrics.com/deadline-for-enrolment-in-saudi-arabia-biometric-registry-looms/ (last accessed 15 April 2019). The identification system connects to a central database that contains all 10 fingerprints of each registrant. In contrast to other similar national ID cards, Saudi Arabia, specifically, has made it illegal to remove the card from the Persian Gulf region.78x ‘National ID’, Ministry of Interior, www.moi.gov.sa/wps/portal/!ut/p/z0/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8ziDTxNTDwMTYy8_Y0dXQ0czdx8LIMsDQw9DQ30g1Pz9L30o_ArApqSmVVYGOWoH5Wcn1eSWlGiH5Gbn6mQklmemKdqAGJm5OemKoAl80pUDUA8VYOi1PTSHLBLwGri86CuUshMiU9JTUsszSmJB1pfkO0eDgACsLK3/ (last accessed 15 April 2019). Although all citizens are required by law to have a national ID, women in Saudi Arabia tend not to have the identification, but the government has a campaign to assure that women are able to receive the required ID.79x H. Toumi, ‘Campaign for Saudi Women to Apply for Individual ID Cards’, Gulf News, 7 November 2018, https://gulfnews.com/world/gulf/saudi/campaign-for-saudi-women-to-apply-for-individual-id-cards-1.2186407 (last accessed 15 April 2019).

Australia has the most modern form of digital identification. To enrol in the identification service, a user downloads an app onto an Android or Apple phone, opens the app and completes the questionnaire, which is electronically verified with government databases.80x ‘Digital ID Help & Support’, Australia Postal Corp., www.digitalid.com/help-support?c=DigApp100#app (last accessed 9 April 2019). The user than takes a ‘selfie’ photo on the phone, which is digitally compared with existing government records.81x Ibid. The user will then take the phone and a passport or driver’s licence to the post office, Australia Post, which confirms the paper documents and activates the digital ID.82x Ibid. After activation, when identification is needed the app will generate a QR code that can be scanned by government agencies and used in financial and other private transactions.83x Ibid. Australia Post owns the URL ‘digitalid.com’, through which it promotes the ID app and offers instructions to users and merchants on how to apply for and use the ID app.

The New Zealand tax authority has a unique experiment in biometric identification: voice ID.84x ‘Voice ID Video’, Inland Revenue, 12 March 2019, www.ird.govt.nz/help/demo/voice-id/voice-id-index.html (last accessed 15 April 2019). A user calls a phone number and recites her or his tax identification number. The voice is digitized, creating a voice print, and saved so that the voice alone can identify the caller in the future. A New Zealand finance minister reported in 2015 that 1.4 million taxpayers,85x ‘1.4 Million Customers Sign up for IRD Voice ID’, The Beehive, 11 June 2011, www.beehive.govt.nz/release/14-million-customers-sign-ird-voice-id (last accessed 15 April 2019). of an estimated population of 4.6 million,86x Estimated population as of June 2015, ‘Population | Stats NZ’, www.stats.govt.nz/topics/population (last accessed 19 April 2019). had registered for the voice ID service. A similar voice ID service is also being used by a New Zealand bank.87x ‘ANZ Phone Banking’ (ANZ), www.anz.co.nz/banking-with-anz/ways-to-bank/phone-banking/ (last accessed 15 April 2019).

An age-old question on what information is part of a person’s ‘identity’ has caused problems for digital identification programmes in Egypt and Afghanistan. Egyptian law requires that all Egyptians have a national digital identification card, which is required to access government services. To apply for the card an applicant must declare his or her religion. However, Egypt allowed the applicant to choose only Islam, Judaism or Christianity as a religion. Applicants who did not choose one of the three recognized religions were refused ID cards. A lawsuit was filed by adherents to the Bahá’í faith claiming that their inability to obtain a national identification card without misstating their religion was a violation of their rights under Egyptian law. In 2008, the Egyptian Court of Administrative Justice ruled in two cases that Egyptian citizens who are not Christian, Muslim or Jewish may have the religion omitted from their identification card.88x Case Nos. 58/18354 and 61/12780, 29 January 2008, Court of Administrative Justice, cited in ‘Freedom of Religion and Belief in Egypt’, Quarterly Report (Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, January-March 2008), accessed 18 April 2019. See also “First Identification Cards Issued to Egyptian Baha’is Using a ‘Dash’ Instead of Religion” (Bahá’í World News Service, 14 August 2009), https://news.bahai.org/story/726/ (last accessed 18 April 2019).

Further complicating the rollout of the digital ID card in Egypt was the difficulty of getting identification cards for women. Identification cards are required in Egypt to obtain access to most government services. However, Egyptian women often do not have such identification.89x ‘Women’s Political Participation in Egypt’ (OECD, July 2018), p. 56, www.oecd.org/mena/governance/womens-political-participation-in-egypt.pdf (last accessed 18 April 2019). Through a United Nations Development Programme called the Citizenship Initiative, over two million Egyptian women have been able to obtain national identification cards.90x ‘Egypt: ID Cards Help Women Proclaim Their Existence’ (UNDP), www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/ourwork/ourstories/a-young-woman_s-pursuit-of-proclaiming-her-existence.html (last accessed 18 April 2019).

In Afghanistan, the distribution of digital identification cards, known as e-Tazkiras, has been delayed several times over disputes over nationalist and ethnic descriptions on the cards.91x H. Shalizi, ‘Who Is an Afghan? Row over ID Cards Fuels Ethnic Tension’, Reuters, 8 February 2018, www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-politics/who-is-an-afghan-row-over-id-cards-fuels-ethnic-tension-idUSKBN1FS1Y0 (last accessed 18 April 2019). Ethnic minorities in Afghanistan believe that the word ‘Afghan’ historically describes members of the Pashtun tribe and that the identification should be related to the name of the country.92x Ibid. The current low adoption rate of the e-Tzkiras has raised concerns about the ability to hold fair elections.93x S. Salahuddin & P. Constable, ‘Afghanistan’s New National ID Card Has Finally Debuted, and It’s Already Plagued by Problems’, The Washington Post, 3 May 2018, www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/afghanistans-new-national-id-card-has-finally-debuted-and-its-already-plagued-by-problems/2018/05/03/b9449ba4-4ee8-11e8-85c1-9326c4511033_story.html?utm_term=.602b76b77017 (last accessed 18 April 2019).

Some non-governmental organizations have also created digital identification to be used for purposes outside of the business needs of the organizations. For example, the financial services industries in Sweden94x ‘BankID’, www.bankid.com/en/ (last accessed 10 April 2019). and Norway95x Ibid. have each created their own ‘BankID’, which, in addition to providing access to automatic teller machines, provides access to government services and also serves as general identification throughout the country. Both countries also make the digital identification available on an app for a mobile phone.3.1 Problems with Nation-Issued Identity

As Aresty and Schmitz argue, “In the 21st century, individuals should have a digital identity not linked to citizenship, and be able to exercise the right to own and control it.”96x A.J. Schmitz & J.M. Aresty, ‘Blockchain Can Empower Stateless Refugees’, Law360 Perspectives, 2 December 2018, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3297182. In a rapidly digitizing and globalizing environment, current national identification systems have a limitation in terms of solving the issues of privacy, portability and interoperability.

Centralized databases of national identities serve as a honeypot for hackers, whose repertory of tools available for breaking in increases faster than digital identity protection can keep them out. Most of the systems require unique login and passwords, which are then stored in a centralized ‘location’ (e.g. keyserver), thereby creating multiple vulnerabilities. There have been a host of data breaches in government systems, with a number of minor ones happening every day without being publicized. The US Postal Service had 60 million records stolen in 2018 owing to poor security,97x J. Biggs, ‘US Postal Service Exposed Data of 60 Million Users’, (TechCrunch, 26 November 2018) , https://techcrunch.com/2018/11/26/the-us-postal-service-exposed-data-of-60-million-users/ (last accessed 12 April 2019). hackers stole 9 million records from the Greek government in 2012,98x I. Steadman, ‘Hacker Arrested for Allegedly Stealing ID Info of Most of Greece’, Wired, 22 November 2012, www.wired.co.uk/article/greece-id-theft (last accessed 11 April 2019). and nearly 2.5 million Syrian government records have been lost or compromised.

In addition to protecting data in their own databases, national governments have been increasingly challenged by unwanted dissemination of personal information kept by corporations. In the most recent case, Cambridge Analytica gained unauthorized access to the personal identifiable information (PII) of 87 million Facebook users and used it for targeted political campaigns worldwide.99x K. Granville, ‘Facebook and Cambridge Analytica: What You Need to Know as the Fallout Widens’, NYT, 19 March 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/03/19/technology/facebook-cambridge-analytica-explained.html. For refugee populations, the security of data is perhaps perceived as even more important than for ‘regular citizens’. Most humanitarian workers would confirm that refugees care about privacy, perhaps because privacy is often related to security and personal safety. -

4 Examples of Non-State-Based Digital Identity Projects

4.1 Truu: The First Self-Sovereign Identity Solution for Health-Care Workers100x https://www.truu.id/.

Created by Dr Manreet (Manny) Nijjar, an infectious disease physician of Indian descent in Kenya who has worked for over a decade in the UK’s National Health Service, Truu addresses the disparity in access to health-care services across the globe. Dr. Nijjar’s work was prompted by observations about the danger of siloed identities for health-care workers in high-stress environments.

A common theme across cultures is the trusted relationships that individuals build up with doctors, nurses and allied health-care professionals.101x Global Teacher Status Index 2018, https://www.varkeyfoundation.org/media/4790/gts-index-9-11-2018.pdf. This has led them to be the most respected and trustworthy professionals across the world.102x Ipsos MORI Veracity Index 2018, https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2018-11/veracity_index_2018_v1_161118_public.pdf.

Built on morals and a code of professional ethics, health-care workers form this trust through their understanding of confidentiality (privacy), consent (control) and respect for an individual’s wishes (autonomy). Nevertheless, this trust can be broken when individual actors, despite the systems in place, cause harm or risk to patients.

One major problem is that doctors interact with multiple organizations, so their identity data is usually siloed. Before Truu there was no easy process for these organizations to communicate with each other to share this information. The administrative burden for both doctors (some of whom can have up to 15 identity checks in a 10-year period) and organizations fuelled a commitment to finding a digital identity solution to solve the problem.

Dr. Nijjar researched centralized, federated and user-centric digital identity systems, all of which were useful for certain cases. However, they did not meet the requirements of portability, privacy, security and scalability required. The conclusion of the research was that a self-sovereign/multi-source identity would work. It would not only increase the level of trust in the current physical world process for doctors, but also bring this trust into the digital world along with the rapid emergence of health technology. Truu is the world’s first self-sovereign identity solution for health-care workers.

Building these technologies offers a great public benefit. Two areas of need and benefit are:Working towards the Millennium Development Goal of universal health coverage, which highlighted the global challenges of an estimated deficit of 14 million global health-care workers by 2035.

Helping doctors, as highly trusted professionals, to cascade this trust (trust waterfall) to people who need this care most, such as refugees in post-conflict areas or individuals in resource-poor countries. By providing health credentials to these people (adults or children) Truu can provide the basis and foundation of their own identities.

For Truu’s approach to work it needed to be built on a global public utility underpinned by open standards and interoperability, with the fluidity and flexibility to cater to local and regional needs, while meeting international standards.

The following technologies and emerging international open standards have allowed Truu to build and develop a trusted digital identity solution for doctors in the UK that can be scaled for health-care workers across the globe.

4.2 Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT)

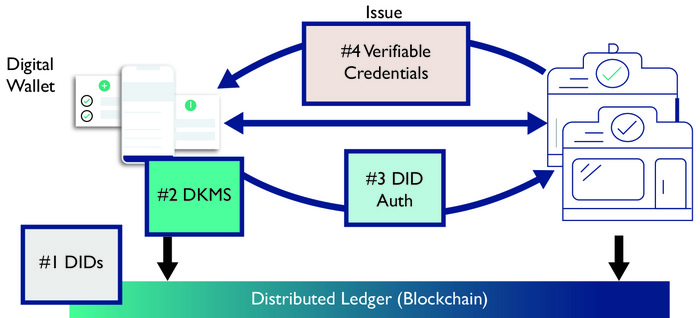

Sovrin Network103x The Sovrin Network, https://sovrin.org/ (last accessed 8 July 2019). is an open-source project creating a global public utility for self-sovereign identity. The Sovrin Network enables people, organizations or IT devices to prove things about themselves to anyone or anything, peer to peer, using data that the other party can verify. When anyone or anything is able to trust whom or what it is dealing with online, massive amounts of friction can be removed, user experience can improve and the transaction processes can be simplified. The Sovrin Network is built on top of Hyperledger Indy, part of the Hyperledger project.

Hyperledger is an open-source collaborative effort created to advance cross-industry blockchain technologies. It is a global collaboration, hosted by The Linux Foundation, including leaders in finance, banking, Internet of Things, supply chains, manufacturing and technology

Hyperledger Indy104x Hyperledger Indy, https://www.hyperledger.org/projects/hyperledger-indy (last accessed 8 July 2019). is a distributed ledger, purpose-built for decentralized identity. It provides tools, libraries and reusable components for creating and using independent digital identities rooted on blockchains or other distributed ledgers so that they are interoperable across administrative domains, applications and any other ‘silo.’

Because distributed ledgers cannot be altered after the fact, it is essential that use cases for ledger-based identity carefully consider foundational components, including performance, scale, trust models and privacy. In particular, Privacy-by-Design and privacy-preserving technologies are critically important for a public identity ledger where correlation can take place on a global scale.

For all these reasons, Hyperledger Indy has developed specifications, terminology, and design patterns for decentralized identity along with an implementation of these concepts that can be leveraged and consumed both inside and outside the Hyperledger Consortium.4.3 Decentralized Identifiers105x W3C A Primer for Decentralized Identifiers, https://w3c-ccg.github.io/did-primer/ (last accessed 8 July 2019).

A decentralized identifier (DID) is a new type of identifier that is globally unique, resolvable with high availability and cryptographically verifiable. DIDs are typically associated with cryptographic material, such as public keys and service endpoints, for establishing secure communication channels. DIDs are useful for any application that benefits from self-administered, cryptographically verifiable identifiers such as personal identifiers, organizational identifiers and identifiers for Internet of Things scenarios. For example, current commercial deployments of W3C Verifiable Credentials heavily utilize Decentralized Identifiers to identify people, organizations and things to achieve a number of security and privacy-protecting guarantees.

4.4 Decentralized Key Management Solution106x Decentralized Key Management System Rebooting Web of Trust #4 Drummond Reed Paris 2017, https://github.com/WebOfTrustInfo/rwot4-paris/blob/master/topics-and-advance-readings/dkms-decentralized-key-mgmt-system.md (last accessed 8 July 2019).

Decentralized key management solution (DKMS) is a new approach to cryptographic key management intended for use with blockchain and distributed ledger technologies where there are no centralized authorities. DKMS inverts a core assumption of conventional PKI (public key infrastructure) architecture, namely that public key certificates will be issued by a relatively small number of centralized or federated certificate authorities (CAs). With DKMS, the initial ‘root of trust’ for all participants is a distributed ledger that supports a new form of root identity record called a DID.

A DID is a globally unique identifier generated cryptographically, so it requires no central registration authority. Each DID points a DDO (DID descriptor object), a JSON-LD object containing the associated public verification key(s) and a pointer to off-ledger agent(s) supporting peer-to-peer interactions with the identity owner. From this baseline, trust between peers can be built up in two ways:Challenge/response messages for real-time verification of public keys.

Exchange of identity attribute claims signed by other trusted peers (‘verifiable claims’) whose public keys can also be verified against the ledger.

This decentralized ‘web of trust’ model leverages the security, privacy and resiliency properties of distributed ledgers to provide highly scalable key distribution, verification and recovery, finally making PKI accessible to everyone.

4.5 Verifiable Credentials107x W3C Verifiable Credentials Data Model 1.0, https://www.w3.org/TR/verifiable-claims-data-model/#what-is-a-verifiable-credential (last accessed 8 July 2019).

In the physical world, a credential might consist of:

Information related to the subject of the credential (for example, a photo, name and identification number);

Information related to the issuing authority (for example, a city government, national agency or certification body);

Information related to the specific attribute(s) or properties being asserted by the issuing authority about the subject;

Evidence related to how the credential was derived;

Information related to expiration dates.

A verifiable credential can represent all of the same information that a physical credential represents. The addition of technologies, such as digital signatures, makes verifiable credentials more tamper-evident and more trustworthy than their physical counterparts. Holders of verifiable credentials can generate presentations and then share these presentations with verifiers to prove they possess verifiable credentials with certain characteristics. Both verifiable credentials and verifiable presentations can be transmitted rapidly, making them more convenient than their physical counterparts when trying to establish trust at a distance.

While this specification attempts to improve the ease of expressing digital credentials, it also attempts to balance this goal with a number of privacy-preserving goals. The persistence of digital information, and the ease with which disparate sources of digital data can be collected and correlated, comprise a privacy concern that the use of verifiable and easily machine-readable credentials threatens to make worse.4.6 DID Auth108x Introduction to DID auth. Rebooting Web of Trust #6 Markus Sabadello et al. July 2018, https://github.com/WebOfTrustInfo/rwot6-santabarbara/blob/master/final-documents/did-auth.md (last accessed 8 July 2019).

The term DID Auth has been used in different ways and is currently not well defined. Truu defines DID Auth as a ceremony where an identity owner, with the help of various components such as web browsers, mobile devices and other agents, proves to a relying party that they are in control of a DID. This means demonstrating control of the DID using the mechanism specified in the DID Document’s ‘authentication’ object. This could take place using a variety of data formats, protocols and flows. DID Auth includes the ability to establish mutually authenticated communication channels and to authenticate websites and applications.

4.7 Tykn: The Future of Resilient Identity109x https://tykn.tech/ (last accessed 8 July 2019).

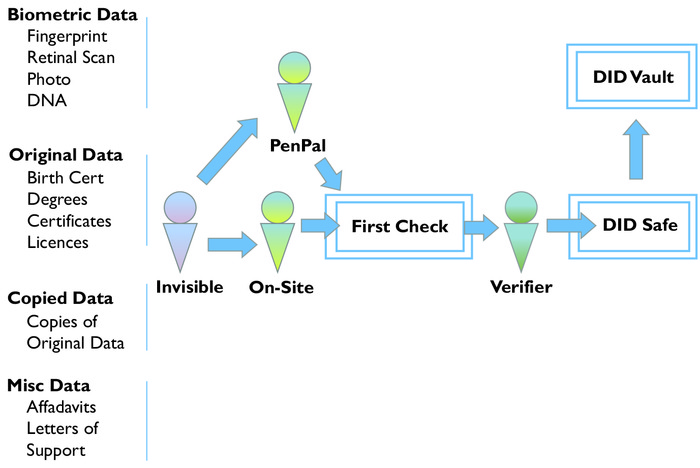

A third of the refugees in Europe are children, and while some are lucky and get documented, hundreds of thousands in Syrian refugee camps do not have birth certificates, and newborns in camps are unable to complete the birth registration process owing to economic, geographical and complex administrative barriers.

Ultimately, the experiences the refugees shared with Tey in the Dutch refugee camp regarding the hardships they suffered as ‘invisible people’ gave him the inspiration and motivation to found Tykn with the ultimate goal of reinforcing identity infrastructures to make them more resilient, providing higher socio-economic inclusion.

Tykn is envisioned not just as a company, but as a movement attacking the multi-headed ‘identity crisis’ problem from multiple angles, focusing on a single goal: transforming the lives of millions impacted by lack of verifiable identity. Experience on the ground creates an inherent understanding that solving for basic identity is just an enabler – true value will be unlocked only once linked benefits can be realized. As such, Tykn’s focus is not just on resolving challenges at the individual level, but also on optimizing the remedy engine and creating the infrastructure of humanitarian agencies and NGOs globally.4.8 Two Types of Credentials

Our identity consists of many different components called credentials (e.g. a name, date of birth or nationality). Tykn distinguishes two types of credentials:

Dynamic credentials: These points of information can change over time, such as one’s place of legal residence or nationality. Dynamic credentials have a tendency to change, with some subject to shorter intervals of change than others. Nationality, for example, can, but will not necessarily, change.

Static credentials: These points of information do not change and are thus deemed static (e.g., one’s date of birth, blood type or family ties). Additional static information can be added, but the basic information will not change.

The only identity document (on- or offline), which has a global standard in terms of format and verification procedure, is a passport, since these are attested to by one of the national governments. National governments are part of a global trust network in terms of identity verification, since the verifying government trusts the issuing government and thus subsequently trusts the identity owner. This concept illustrates the importance of identification rather than identity, which in itself is useless without this trust network that allows interoperability and multipurpose usage. Within the digital realm, only siloed versions of identity exist, since there is no global network of identity attestors that can provide a single verified and interoperable identity. Issuers create a single-purpose usable identity in the form of an account for their respective use case. This means that identity owners hold an array of different accounts with a single use, instead of a single one with full interoperability. The real problem of identity lies in identification.

The Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI)110x https://hhi.harvard.edu/ (last accessed 8 July 2019). has distinguished five fundamental rights in humanitarian information activities to protect information rights, but these also apply to all other identity owners.Right to protection Every person should be protected from (in)direct harm in terms of life, liberty and personal security from the information and communication technology (ICT) services or data that is related to them, with respect to the potential misuse of this data that could cause harm.

Right to information Access to information and methods of communication have become a basic human right. They should be able to generate, access, acquire, transmit and benefit from information, specifically in the context of crises.

Right to privacy and security The basic human right that a person’s data is treated with ethical, technical and legal standards for the protection of individual privacy, consistently.

Right to data agency The collection, use and disclosure of PIIs should lie within the agency of the data owner. Also, the misuse of aggregated personally identifiable information (PIIs) into DIIs, could lead to information threat through breaches on a population level.

Right to rectification and redress When a person’s collected information is false, inaccurate and/or incomplete they hold the right to rectification. A person should have the right of access to all personal information collected on themselves. When there is (in)direct harm as a result of this, relevant parties should be able to redress this.

4.9 InternetBar.Org: Secure DIDs Enable Trusted Online Communities