the current development of mediation and other ADR tools in this field

the importance of ODR as a mechanism for all forms of dispute resolution

the emergence of legislation impacting upon ODR.

Examine the need and extent to which ODR practice should be self-regulated through an independent international credentialing scheme and how such self-regulation can be most effectively implemented, including:

1.1. COMPETENCY

1.1.1. competency criteria (knowledge, skills and experience) that individual ODR practitioners should possess to practice in ODR;

1.1.2. best practice and competency criteria (knowledge, skills and experience) for those advising or representing parties engaged in ODR;

1.2. STANDARDS

1.2.1. standards that need to be met by ODR service providers, ISPs, hosts, platforms and software to fully address the needs and protect the interests of users [1];

1.2.2. standards of trainings and codes of professional conduct.

1.3. COMPLIANCE

1.3.1. how compliance with such criteria can be effectively and economically assessed and monitored on a self-regulatory basis; and

1.3.2. the need to develop a Code of Conduct and Disciplinary Process for ODR.With regard to the growing use of ODR in cross-border dispute resolution and existing and planned government regulation in this field, identify the infrastructure needed to develop ODR standards on both national and international levels; assess the relevance of inter-operability, data import/export/migration and language translation.

Propose other measures or initiatives to support the development of quality ODR.

Define ODR

Tools

ODR Practitioners (standard competencies)

Advising and Representing Parties

ODR Service Providers

Trainings and Code of Professional Conduct

Assessment

E-mediation Competencies

E-mediation Skills

General Requirements for E-mediation QAPs

credibility and reliability, which are based on the professional and technical abilities of the practitioner;

intimacy, which depends on the capability to develop a safe and deep rapport; and

self-orientation, which refers to the practitioner’s focus – primarily on self or on the other. Self-orientation diminishes trust, while ‘other’ orientation increases trust.

self-confidence about technology and mediation abilities (both techniques and process);

high social emotional intelligence to develop intimacy – to foster an ‘other’ (vs. self) orientation with all parties despite low media richness;

situational awareness – attention to the context and adaptability to all circumstances, managing technical pitfalls with effectiveness and mindfulness;

ethical behaviour adapted to the online constraints and opportunities.

-

Situational Awareness

1. Knowing when the online environment may not be a suitable way to conduct the mediation process;

2. Determining when Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) approaches are likely to add value to the process;

3. Staying abreast of developments in ICT, ODR schemes, various ODR platforms and general issues related to ODR;

4. Knowledge about the impact of ICT on the practice of mediation.

-

Basic Knowledge

5. Understanding the principles of text-, video-, and audio-based communication (or a combination) and ability to identify the most appropriate one for a mediation or for phases of the mediation process;

6. Understanding of the role of a mediator, and how the mediator’s approach and practice are adaptable or not to the online environment;

7. Knowledge and adherence to ethical standards;

8. Knowledge of the dynamics of online negotiation;

9. Knowledge of relevant laws affecting mediation practice in the online environment (if any): enforceability of online mediation agreements (where relevant), confidentiality and privilege;

10. Knowledge of the various laws affecting the structure and enforceability of online mediation agreements, particularly across jurisdictions.

-

Platform/Technology

11. Ability to select the appropriate ICT platform that meets the needs of the parties;

12. Knowledge about which features of the ICT platform to use in a mediation (functions, security, access, complexity, others);

13. Knowledge (as applicable) in technology (hardware and software) (i) devices needed to perform the mediation using ICT; (ii) telecommunications technology; (iii) information technology; (iv) required electronic records;

14. Knowledge about possible technology issues and breakdown.

-

Process/Impact

15. Understanding of the emotional, social and cognitive advantages and disadvantages of using ICT in a conflict resolution process and the ability to measure and manage the impact and effects on third parties;

16. Ability to move between different communication channels on the basis of the nature of the relationship and task at hand (e.g. use of email to coordinate a call, use the phone before going to a face-to-face meeting and then shift back to phone before writing again a final email);

17. Understanding of biases related to ICT use and impact on parties and third parties’ performance in mediation;

18. Knowing how to use relevant procedures and techniques for facilitating online communication including (i) management of asynchronous communication and (ii) balancing limitations of each ICT towards the needs of each party;

19. Familiarity with the impact of the online environment in techniques such as listening, questioning, paraphrasing, summarizing and concurrent caucusing.

-

Communication With Parties

20. Understanding and explaining to the parties policies, procedures and protocols relevant to conduct the mediation using ICT. Including but not limited to:

20.1 Ethical and legal issues: (i) consent, privacy, confidentiality, security and (ii) limitations of technology;

20.2 Documentation: (i) scheduling and follow-up; (ii) accountability/responsibility and (iii) enforceability;

21. Understanding of technological challenges and ability to identify them for each participant, including but not limited to literacy, acceptance and compatibility;

22. Knowing how to use techniques for adequately supporting technologically challenged participants and address possible imbalances between parties;

23. Knowledge of cultural bias related to the use of technologies in mediation practice.

Appendix 2. E-Mediation Core Competency Practical Skills -

1. General Skills in Mediation (IMI Certification)

Those skills include but are not limited to ethical obligations, neutrality, awareness of potential biases (conscious and unconscious) and confidentiality.

-

2. Skills Related to Technology:

2.1 Basic computer skills and basic mobile computing skills;

2.2 Working with ICT platform set-up, operation, and trouble-shooting;

2.3 Ability to manage efficiently any technology challenges;

2.4 Ability to use the technical equipment and environment (e.g. lighting, sounds, distractions) in order to deliver a high-quality experience to participants of the respective e-Mediation;

2.5 Ability to convey clear and effective messages in verbal and non-verbal communication synchronously and asynchronously;

2.6 Ability to use the ICT platform in such a way that the platform does not take away the focus from the content of the conversation with/among the parties;

2.7 Ability to show confidence and critical self-awareness in working with technology to address parties’ issues;

2.8 Ability to simultaneously address people who are in different countries and regions and different time zones – understanding the impact that this can have on the dynamics of the communication;

2.9 Understanding implications for privacy in storing digital information and communicating with parties and others online;

2.10 Ability to combine asynchronous communication and videoconferencing in order to manage caucuses;

2.11 Ability to use specific options of the ICT platform such as (i) meeting planning, (ii) screen sharing, (iii) online caucus, (iv) giving mouse controls, (v) muting and unmuting, (vi) multiple webcams and (vii) multiple modes of communication simultaneously.

-

3. Skills Related to the e-Mediation Process

3.1 Assessing suitability of the dispute/disputants to e-Mediation;

3.2 Determining which approaches are likely to add value to e-Mediation;

3.3 Determining and explaining to the parties the impact of the use of ICT in terms of process and potential impact on the outcome of mediation;

3.4 Dealing with the different levels of readiness of the parties to accept the implication of using ICT in the mediation process, evaluating and securing equal access to ICTs for all parties involved;

3.5 Determining special costs or fees associated with the use of ICT in e-Mediation;

3.6 Preparing for e-Mediation

Considering parties’ knowledge of mediation process and impact of ICT;

Understanding the level of technical knowledge of the parties and their capacity to communicate effectively using ICT platforms;

Guiding parties and all participants through the ICT (the process and information management);

Identifying possible outcomes, risks and consequences associated with e-Mediation;

Identifying and explaining to the parties (in common language) the potential risks in relation to privacy and confidentiality while using online or computer-based platforms or applications;

Identifying and communicating common technical issues, problems or questions that may arise during an e-Mediation process and providing parties with possible protocols to address them;

Identifying reasonable industry standards for security and privacy protection of a determined online or computer-based platform and refraining from using or recommending the ones that do not meet those standards;

Creating a protocol agreement that defines the parties’ understanding of the process, the use of any ICT, the potential risks to their information and the responsibilities of an e-Mediator (including responsibilities related to confidentiality and ability to provide protection to data transmitted online);

Choosing the online platform that is going to be used during the e-Mediation;

Getting agreement regarding who will be present during the different audio and/or video sessions of the e-Mediation;

Getting agreement regarding who will have access to any information stored online as part of the mediation process and define how that access is going to take place;

Creating an atmosphere where the use of ICT by the e-Mediator outside of the mediation does not create the perception of a conflict of interest by the parties;

Identifying and getting agreement on the procedure to follow in case of technology breakdown;

Disclosing the appropriate information so the e-Mediation can be conducted without any conflict of interests; ensuring transparency with regard to the e-mediator, the institution, the fourth party and the online procedure;

Identifying the parties’ understanding of the sources of the dispute, their interests, rights and options, and the other party or parties’ interests, rights and options.

3.7 During e-Mediation

Effectively using technology and outside assistance if needed;

Conducting a high-quality process within the online environment;

Deciding on the best online process that meets the needs of the parties despite personal preferences or bias in favour or against the use of ICT;

Monitoring of the parties’ perceptions and attitudes towards the e-Mediation and adjusting the process respectfully;

Being aware of the different features of the ICT platform, their corresponding advantages and constraints to be able to discern which feature to use in which context;

Understanding and dealing with technology impact in power imbalances (e.g. typing capabilities of the parties, imbalance due to computer power and Internet speed, others);

Monitoring to ensure that parties deal with the online process on equal ground and competence;

Being self-aware to avoid becoming biased by party’s performance using ICT;

Taking advantage of the change of communication type provided by online dispute resolution mechanisms to help the parties take the most out of the situation (e.g. create space for brainstorming, time to reflect);

Understanding how to adapt text-/audio-/video-based communication to the kind of issue parties are discussing;

Applying emotion management techniques;

Understanding how to use active listening online that also includes attentive and active reading;

Using ICT to facilitate negotiations in an efficient way;

Ensuring that impartiality is maintained;

Exhibiting lack of bias related to considerations of geographical location or cultural orientation of e-Mediator or use of facilities;

Ensuring that the e-Mediator’s conduct is always professional and appropriate (respecting the protocol agreement regarding the access to parties, responsiveness to parties’ requests, taming tempers);

Managing the continuation and the termination of the e-Mediation (addressing parties’ hanging up, technical failure, automated processes, etc.);

Understanding how to translate face-to-face mediation techniques into the online environment.

3.8 Reaching agreement

Ensuring parties have given their informed consent;

Ensuring that agreement addresses issues, interests and rights as identified throughout the process.

3.9 Post-mediation process

Encouraging parties to provide feedback on their experience in e-Mediation;

Conducting follow-up when needed.

- * The observations in this document are based on the presentation by Ana Maria Gonçalves at the 2018 International ODR Forum in Auckland, New Zealand.

-

1 The authors will proceed with the assumption that every mediator working today uses some information and communication technology (ICT) in her or his practice because ICT is such a central feature of contemporary life. Even if the practitioner uses only a smartphone, laptop, or desktop, her or she is engaged in a form of online dispute resolution and is, by default, an e-mediator.

-

2 See, e.g., the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States, where one of the authors lives and practices, has a set of mediator qualifications that are illustrative of ‘normal’ basic mediator certification requirements. A copy of the requirements can be found at: www.courts.state.va.us/courtadmin/aoc/djs/programs/drs/mediation/training/tom.pdf.

-

3 The Model Rules and comments are currently available at: https://docs.google.com/a/danielrainey.us/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid=ZGFuaWVscmFpbmV5LnVzfHJhaW5leS1wdWJsaWNhdGlvbi1maWxlLWNhYmluZXR8Z3g6MTZhYTAyNjQ1NTliYWE4OA.

-

4 Available at: http://odr.info/ethics-and-odr/.

-

5 NCSC has published many articles related to technology and the courts, available at: https://www.ncsc.org/Topics/Technology/Technology-in-the-Courts/Resource-Guide.aspx.

-

6 ICODR’s home page is available at: http://icodr.org/.

-

7 The initial survey was done by Orna Rabinovitz-Einy and Rachel Ran as a contribution to IMI ODR Task Force, with additions by the authors. The EU Regulation concerns only disputes arising from domestic online transactions within the EU.

-

8 K.W. Rockmann & G.B. Northcraft, ‘To Be or Not to Be Trusted: The Influence of Media Richness on Defection and Deception’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 102, No. 2, 2008, p. 107.

-

9 Ibid.

-

10 Ibid.

-

11 Ibid.

-

12 Ibid.

-

13 Ibid.

The standards of practice, qualifications, and certifications for mediators and e-mediators is important because the basic ethics and standards of practice for mediators form a ‘mainstream’ set of guidelines for attitudes and behaviours that widen out into use in all forms of conflict engagement.1xThe authors will proceed with the assumption that every mediator working today uses some information and communication technology (ICT) in her or his practice because ICT is such a central feature of contemporary life. Even if the practitioner uses only a smartphone, laptop, or desktop, her or she is engaged in a form of online dispute resolution and is, by default, an e-mediator. Creating trust with the parties in conflict is basic to mediation, and it is basic to work in facilitation, conciliation, peacebuilding, and other forms of conflict engagement. Likewise, ensuring party self-determination is central to mediation and is a concern of practitioners in other forms of conflict engagement. It is not the case that standards and qualifications for mediators can be adopted seamlessly for other types of practice, but it is the case that standards and qualifications for mediators can inform the development of standards and qualifications in other types of practice.

What makes a competent mediator? How do the parties in conflict know that the third party they have chosen to work with them is skilled and able to assist without doing harm? This question is hard enough to answer when the question is being asked of mediators who work primarily face to face. Requirements vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and from country to country, but a de facto standard seems to exist on the basis of the 40-hour basic training outlined by courts as a way to certify mediators accepting court-referred cases. Some distinctions are usually made among civil cases, family mediation cases, and the like, but the 40-hour basic training is commonly used as a starting point.2x See, e.g., the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States, where one of the authors lives and practices, has a set of mediator qualifications that are illustrative of ‘normal’ basic mediator certification requirements. A copy of the requirements can be found at: www.courts.state.va.us/courtadmin/aoc/djs/programs/drs/mediation/training/tom.pdf.

So, if a mediator completes the 40-hour course and engages in the usually required co-mediation or mentoring, does that guarantee competence? If the mediator has conducted a thousand mediations, does that signify competence? Judging competence in any field that features human interaction in complex situations is at best fraught with problems. Judging competence in mediation, which is managing human communication in conflict situations, is particularly fraught because, unlike the law or medicine or other professions, there is no central authority that certifies, trains, and monitors performance. If this problem exists for mediation, it is potentially magnified for e-mediation.

For e-mediation there is another complicating factor. There are guidelines for training mediators scattered around the world, and there are de facto standards for what basic mediation training should include. But not one of the many training programs in mediation, anywhere in the world, to the knowledge of the authors, features a segment on the use of technology in mediation. There are courses in universities that focus on online dispute resolution (ODR) but those courses are not, to the authors’ knowledge, integrated into basic mediation training for practitioners seeking certification from any of the court systems that have established basic training criteria.

There are a number of organizations engaged in work related to e-mediation and ODR standards of practice, qualifications and certification. The Association for Conflict Resolution (ACR) will soon publish a set of comments on the Model Rules for Mediators that were adopted by the ACR, the American Bar Association (ABA) and the American Arbitration Association (AAA) in 2007.3xThe Model Rules and comments are currently available at: https://docs.google.com/a/danielrainey.us/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid=ZGFuaWVscmFpbmV5LnVzfHJhaW5leS1wdWJsaWNhdGlvbi1maWxlLWNhYmluZXR8Z3g6MTZhYTAyNjQ1NTliYWE4OA. The National Center for Technology and Dispute Resolution (NCTDR) has published a set of ethical principles guiding development and practice in ODR.4xAvailable at: http://odr.info/ethics-and-odr/. The National Center for State Courts (NCSC) is engaged in the process of developing guidance for court systems to use as they advertise for alternative dispute resolution (ADR) and court technology.5xNCSC has published many articles related to technology and the courts, available at: https://www.ncsc.org/Topics/Technology/Technology-in-the-Courts/Resource-Guide.aspx. The International Council for Online Dispute Resolution (ICODR) has recently been formed and will have as one of its mandates the creation of standards for various types of ODR work.6xICODR’s home page is available at: http://icodr.org/.

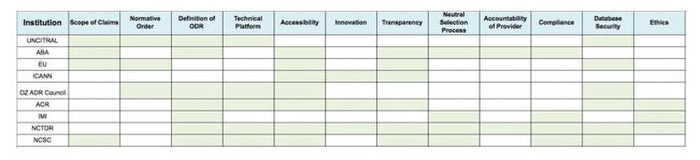

A survey of organizations that have offered some guidance regarding ODR reveals that, although there are a number of published guidelines for ODR, each has gaps.7xThe initial survey was done by Orna Rabinovitz-Einy and Rachel Ran as a contribution to IMI ODR Task Force, with additions by the authors. The EU Regulation concerns only disputes arising from domestic online transactions within the EU. One of ICODR’s goals is to provide guidance consistent with the work that has already been done and to offer a set of guidelines that address all of the major issues surrounding ODR.

The International Mediation Institute (IMI) has published a set of e-mediation skills and e-mediation certification standards. At the 2018 International ODR Forum in Auckland, New Zealand, the new e-mediation standards were presented to the forum attendees.

Created in 2008, IMI is the only organization in the world to adopt an international vision and mission for mediation. IMI is a non-profit organization registered in The Hague, supported practically and financially by corporate users and by a group of international ADR service providers. IMI aims to address the needs of all stakeholders, starting with users, that is, disputants. This requires also understanding the interests of the other players in the dispute resolution field – mediators, conciliators, law firms and others who advise users, adjudicators, such as judges and arbitrators, service-providing organizations, trainers and educators, and policy-makers.

IMI believes that quality is critical if mediation is to continue to grow and be used by disputants. Mediation is not a recognized independent profession in any country of the world, meaning virtually anybody can call herself or himself a ‘mediator.’ IMI has set out to change that through the transparent establishment of high competency standards that enable users to know that when they select a mediator, they are procuring the services of a quality professional who has the skills to assist them in resolving their dispute.

IMI’s quality standards are established and maintained by IMI’s Independent Standards Commission (ISC), a body of users including highly experienced mediators, leading judges, providers, trainers and educators from 27 countries, with more than 70 members. The standards are applied in practice by service provider organizations that are approved by the ISC to run ‘Qualifying Assessment Programs’ (QAPs). QAPs then assess and qualify experienced and competent mediators for IMI certification. There are currently over 500 IMI-certified mediators in 45 countries. All members of the ISC and all QAPs are listed on the IMI website at www.IMImediation.org.

In 2014, the ISC started to work on ODR standards, using a robust process defined previously and refined while working on other key critical topics such as inter-cultural competencies, investor-state mediation, and mediation advocacy. At the 13th Annual International Online Dispute Resolution Forum, hosted by Stanford Law School, an ODR Task Force was created, gathering more than 30 thought-leaders and ODR professionals from more than 8 countries and co-chaired by Daniel Rainey and Ana Maria Maia Gonçalves. The ODR Task Force first agreed on the following terms of reference:

To define online dispute resolution (ODR) and to assess and make recommendations on how to develop high-level standards for the provision of ODR services, having regard to:

In particular, to study and make recommendations in relation to the following key areas, which have a long-term impact on the ODR sector:

Based on this preliminary work, the ODR Task Force organized itself into seven subgroups:

Based on the recommendations from subgroup 3, the ODR Task Force agreed that its original scope of work about ODR Practitioners, as outlined above in point 1.1.1. of its terms of reference, was very broad and, to be true to IMI’s mission, decided to focus on three key deliverables:

The ODR Task Force agreed on the following definition of e-mediation: “The application of any ICT to the process of mediation online or via any other technology” and decided to focus accordingly on precisely defining what skills and competencies an e-mediator shall have so that she or he could be successful in creating trust in the online environment with the different stakeholders of the e-mediation. On the basis of existing literature, the concept of trust appeared to be central to the success of e-mediation. There is until now no scientific study that focuses on the impact of the diverse online technologies on mediation. Nonetheless, one paper published in 2008 highlights the influence of affective and cognitive trust and of media richness on two behaviours that are critical in mediation and negotiation, defection and deception. As defined in this article, media richness is “the ability of a communication medium to transmit different types of information from sender to receiver”.8xK.W. Rockmann & G.B. Northcraft, ‘To Be or Not to Be Trusted: The Influence of Media Richness on Defection and Deception’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 102, No. 2, 2008, p. 107. Defection occurs “when cooperation has been agreed to, yet, because of uncertainty in the environment or willingness to take advantage of others, an individual chooses not to cooperate”.9x Ibid. For its part, deception is the “willful attempt to mislead others through information that is known to be untrue”.10x Ibid. Trust, which is widely recognized as a critical prerequisite to cooperation, is “one’s expectations, assumptions, or beliefs about the likelihood that another’s future actions will be beneficial, favourable, or at least not detrimental to one’s interests”.11x Ibid. It can be divided into two components: cognitive-based trust, “indicated by beliefs in an other’s ability, reliability, and comprehension of the situation”,12x Ibid. and affective-based trust, which “reflects the emotional bonds between members and is indicated by one’s confidence that others’ will act in my best interest because of the bond we have between us”.13x Ibid. The study reveals that defection and deception are more likely to occur the leaner the communication medium used by a group. It is probably common sense to anyone who has used an online communication system that affective-based and cognitive-based trusts are weaker for individuals in groups using a leaner medium. But the most critical findings of the study were that affective-based and cognitive-based trust both mediated the relationship between media richness and defection. Said differently, a leaner communication medium negatively impacted affective-based and cognitive-based trust, which in turn influenced deception or defection. It can be inferred that e-mediators would probably benefit from focusing on developing trust online even more than offline. Other research showed that trustworthiness was the result of the combination of three variables:

Guided by these findings, the ODR Task Force thus recommended that the critical competencies and skills of the e-mediator should be:

In a nutshell, the e-mediator should be an ‘online role model’ for trust-building. The full standards produced by ODR Task Force are listed in Appendices 1 and 2 to this article. At the time of this publication, the ODR Task Force is working on the full publication of the QAP program application, on the definition of the QAP assessment mode, on the launch of IMI e-mediator certification and the creation of a panel of e-mediators on the IMI website.

To date, the creation of standards, qualifications, ethics, standards of practice and competence guidelines for ODR has taken the same general path that standards and the like have taken for offline dispute resolution. Various interested organizations have developed documents and guidelines for specific practice areas, with little or no coordination. We can hope that the creation of ICODR, and the work done by IMI, will begin a process of establishing norms that can be, if not universal, at least widely accepted.

In the end, it would be beneficial for everyone if ODR advocates and practitioners around the world could begin to answer the question that we posed to begin these notes: what should be expected from ODR programs, and what exactly is a competent e-mediator?