-

1 Introduction

Most reports about new ODR implementations, such as those highlighted in this journal, have come from developed economies. This is hardly surprising: it reflects both the fact that digital markets are generally broader and deeper in those nations and also that the recognized pioneers in the field have tended to be based there. However, the relative lack of reports from emerging markets likely understates the growing prevalence of ODR in the lives of consumers in emerging market who are increasingly shopping online. The shortage of reports also may mislead observers as well as policy makers in developing markets to draw the conclusion that ODR is only or mainly for developed markets. On the contrary, this article argues that there are powerful forces at work broadening access to digital justice in developing countries. However, these forces in themselves will not close what Katsh and Rabinovich-Einy (2017) have called the ‘digital justice gap’: the shortfall between the need for or expectation of digital justice and the extent of its deployment. This gap may even be widening as the volume of digital transactions rises faster than effective ODR deployments. To narrow this gap will require reputable private sector players and regulators to make concerted efforts. For this reason, it is important that ODR is re-framed in a way that is relevant and accessible in the increasingly sophisticated discourses emerging around the deployment of digital technology in financial regulation and in forms of e-government.

-

2 Forces Driving Greater Access to Digital Justice

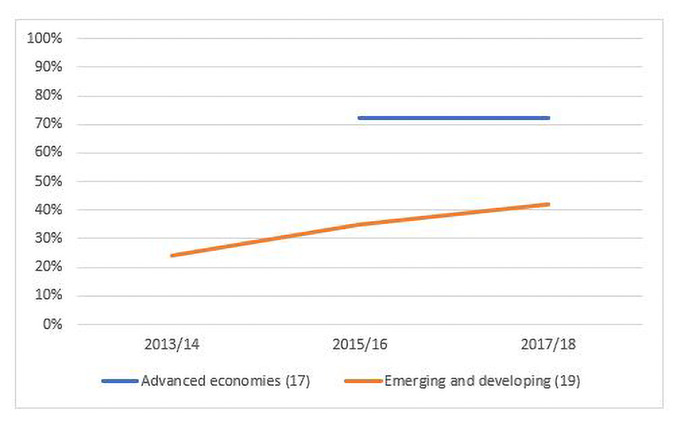

The scale of online activity ultimately drives both the need for ODR and also the potential for access to it. This is because increasing usage of and comfort with digital channels, and their increasing integration into daily life, are prerequisites for their widespread acceptance as means of dispute resolution. The increasing ownership of smart phones around the world may be the most significant force driving deeper online experiences in emerging economies. Figure 1 from rounds of surveys undertaken by Pew Research Center shows that while the proportion of adults owning smartphones has remained stable in advanced economies at around three quarters, in their survey sample of 19 large emerging and developing countries, it has almost doubled in the past 5 years from 26% to 42% on average. In the next few years, most observers expect that more than half of the adults in emerging economies will own a smartphone.

Figure 1: The Proportion of Smart Phone Ownership Increases Source: Pew Global Survey (2018), report available at: www.pewglobal.org/2018/06/19/social-media-use-continues-to-rise-in-developing-countries-but-plateaus-across-developed-ones/#table

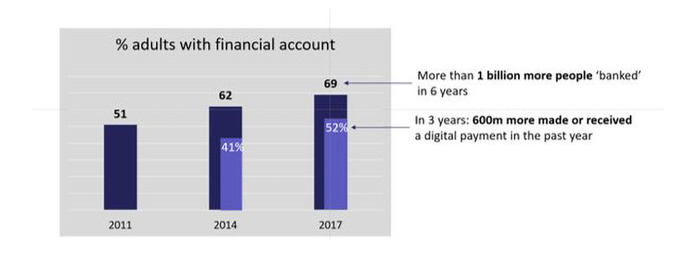

Source: Pew Global Survey (2018), report available at: www.pewglobal.org/2018/06/19/social-media-use-continues-to-rise-in-developing-countries-but-plateaus-across-developed-ones/#table Of course, owning a connected device is necessary to get online, but it is not sufficient to generate online usage: for that, consumers have to be able to use the device in new ways that they find compelling. Many leading applications such as Facebook or Google are free for consumers to use, but increasingly people around the world are also able to buy goods and services online. This has been enabled by a remarkable growth in the number of adults worldwide who are considered financially included because they have a financial account – which in most cases is still issued by a bank. Since consistent global measurement began with the first round of the World Bank’s Global Findex Survey in 2011, close to a billion more people have opened financial accounts. This has raised the proportion of adults considered financially included to 69% in 2017 as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: E-commerce and Digital Financial Inclusion Increase Source: World Bank Global Findex data, various years

Source: World Bank Global Findex data, various years Perhaps even more significantly than having an account, more than half of adults worldwide in 2017 reported making or receiving a digital payment in the past year. Digital payments are made for a wide variety of purposes, including paying bills and sending remittances to friends and family; however, e-commerce, the buying of goods and services online, now makes up an important share. In 2017 when Findex started to ask this question, 29% of adults worldwide reported buying something online.

Many of these purchases would have been made through a major e-commerce platform such as Amazon or Taobao or T-mall (the platforms of the Alibaba Group). These platforms already build in at least some form of online dispute handling and resolution, even though the extent of automated resolution happening in the background may not be evident to the user. This spread of e-commerce is why it is likely that more people than ever before are already exposed to some form of ODR. However, the quality and type of ODR is generally unknown and unmeasured and may indeed be hard to measure since much is concealed in proprietary processes and algorithms. -

3 Forces Driving Greater Need for Digital Justice

The preceding section has made the case that there is more potential for access to ODR than ever before and that there may even be more access than ever, when one considers the spread of e-commerce. In this section, I build the argument that, notwithstanding these positive trends, the digital justice gap is likely still widening in developing countries. To see this, consider examples from the financial services and e-commerce sectors emerging around the world.

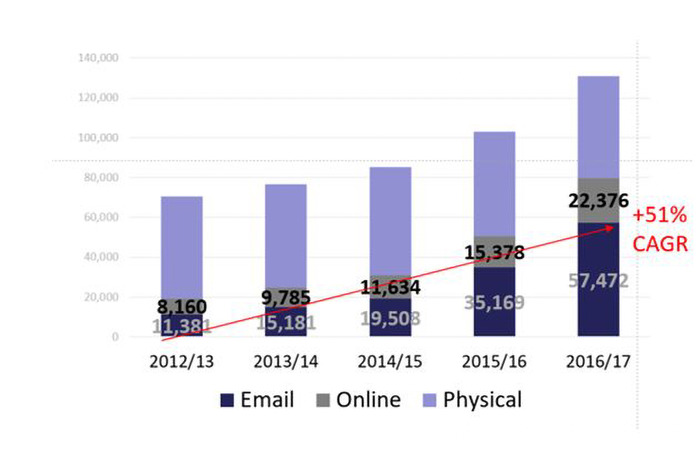

First, in some countries, financial ombuds schemes, sometimes operated by the financial regulator, provide consumers with recourse if they are treated unfairly or unlawfully by a financial service provider and unable to resolve the dispute directly. For example, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) operates one of the largest ombuds schemes, which reports annually in some detail on trends in the number, nature and form of disputes. Figure 3 shows the 5-year trend in the total annual number of ‘matters handled’ by the RBI Ombuds, broken down by how the issue was notified to the RBI.Figure 3: Matters Handled by the Reserve Bank of India Financial Ombuds by Channel Received Source: Annual Report RBI Ombudsman Scheme various years, Table 5

Source: Annual Report RBI Ombudsman Scheme various years, Table 5 Two features are immediately noticeable in this figure. First, the overall volume has almost doubled in 5 years. Second, the channel composition has changed, with email complaints growing at compound rates of 51% per annum, and together also with online complaints, making up more than half of all complaints received. This reflects growing adoption of these channels in India. Physical channels still remain important in India, however, although the channel of receipt may not limit the mode of resolution in future: improving natural language processing capability to render voice into text will mean that even issues logged via call centre may be resolved in automated fashion in future as well.

E-commerce complaints are usually outside of the ambit of financial regulators. In fact, in many places, it is not clear in whose ambit they do fall, other than that of the platform or provider, which is the first line of defence. Meanwhile, as e-commerce volumes rise, so too do problems experienced: for example, 52% of Nigerian e-commerce buyers reported a problem while shopping online in 2016. Of these, 41% reported that the issue was not solved to their satisfaction.1xK. Sodangi, ‘Country Experience: Nigeria’, ONC in ICT Ministry, paper delivered at Africa E-commerce Conference Nairobi, July 2018. Not only does this high rate reflect harm done to consumers, but it also likely harms providers too because a lack of effective resolution adds costs2xThe same survey showed that 15%, almost 1 in 6, of goods bought are returned in Nigeria. and saps consumer trust, and therefore willingness to buy online.

Another factor that is contributing to the growing digital justice gap is the changing patterns of digital payments. On the basis of the transaction data collected from major e-commerce markets around the world, Worldpay’s Global Payments Report 20183xAvailable at: https://www.worldpay.com/global/insight/articles/2018-11/global-payments-report-2018. forecasts that the proportion of e-commerce payments made by credit and debit cards will decline from 43% of the global total in 2016 to 23% in 2021. This squeeze is caused by the rise of e-wallet payments (of which a leading example is Alipay in China or PayPal elsewhere), which are forecasted to constitute almost half (46%) by 2021. These e-wallet transactions are not subject to the same rules as the large card associations, which provide globally consistent frameworks for resolving disputes between card acquirers and card issuers. Instead, e-wallet schemes function under rules set by the scheme operator. This does not mean that there is no protection – on the contrary, firms such as Ant Financial, the owner-operator of Alipay, and PayPal have developed sophisticated systems for handling disputes. But the same standard may not apply to all their present and future competitors. -

4 Reframing to Increase Adoption and Usage

The need for better consumer redress mechanisms has been on the agenda of financial regulators for a while. Principle 6 of the 2011 OECD/G20 Financial Consumer Protection (FCP) principles states,

Jurisdictions should ensure that consumers have access to adequate complaints handling and redress mechanisms that are accessible, affordable, independent, fair, accountable, timely and efficient. Such mechanisms should not impose unreasonable cost, delays or burdens on consumers.

However, the recent OECD/G20 report on Financial Consumer Protection in the Digital Age (OECD 2018), which provides guidance on how to implement the principles, does neither mention ODR specifically nor cite any examples of how member states are using it.4xOECD/G20, 2018, available at: https://www.gpfi.org/sites/default/files/documents/G20_OECD_Policy_Guidance_Financial_Consumer_Protection_Approaches_in_the_Digital_Age.pdf. Silence does not necessarily mean inaction, however: consumer redress is just one of a growing list of issues and challenges on the radar of financial regulators in this area. To ensure that regulators direct adequate attention towards supporting and enabling the emergence and evolution of ODR as a solution to the redress issue, it is necessary also to frame ODR in ways that reflect its relevance to issues already on the regulatory agenda. In this section, I discuss two prominent issues that have risen in the agenda of digital government worldwide.

4.1 ODR as a Key Part of Regtech

The term ‘regtech,’ an abbreviation of regulatory technology, was first coined by the United Kingdom’s Financial Conduct Authority in 2015.5x See FCA’s original call for input on regtech in 2015 available at: https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/call-for-input/regtech-call-for-input.pdf. It was intended as a subset of the broader domain of ‘fintech,’ referring specifically to the use of technology to reduce the growing burdens of compliance on financial providers, as well as to regulators themselves using technology to provide more effective and efficient oversight of financial service providers and markets. The term is now used widely to refer to a range of technology applications that improve regulation, ranging from tools for better reporting to machine learning tools for analysis of suspicious transactions. In a listing of some 74 existing regtech solutions vendors compiled in 2018 by the Regtech for Regulators Accelerator,6x See http://vendors.r2accelerator.org/. It is possible that some of the 56 providers listed under consumer protection may offer ODR solutions but this is not indicated or highlighted separately. dispute resolution does not yet feature as a separate or distinct category. And yet it should: a variety of tech providers provide a range of tools in the space that could be relevant to regulators and providers alike, which seek better and fairer means of grievance redressal.

This absence of ODR solutions in an area in which financial regulators are paying increasing attention is an example both of the need for reframing ODR in its relevance and of the potential to achieve this.4.2 ODR as a Layer in the Country e-Government ‘Stacks’

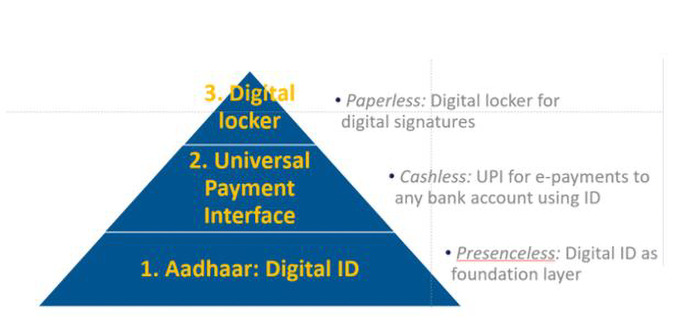

A ‘stack’ is a technology term that refers to a layered set of interoperable programs or protocols: the Internet, for example, is in fact a stack of protocols that govern different layers of operation. In recent years, the term has come to be applied to a set of functions that are required for digital government, which also can and should operate in layers that may be independently managed and provided, but interoperable. This usage of the term, as in a country ‘stack,’ arises from emerging developments in India, where several layers of digital government have been put in place in recent years. Figure 4 shows the current layers in place of the India stack, as described by the Indian non-governmental organization (NGO) most associated with the development and now promotion of the wider vision, iSPIRT.7x See https://ispirt.in/. The foundational layer is that of digital identity, which in the case of India is provided by Aadhaar numbers, which have now been issued to almost 90% of Indians since 2009.8x See report in the Times of India, March 2018, available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/aadhaar-covers-over-89-population-alphons/articleshow/63202223.cms. These numbers provide a unique reference to people whose attributes can be authenticated online. On top of this layer, other layers – for digital payments from any account to any account and for digital signatures and certificates to be stored – have been added in recent years.

The concept of the India stack has attracted increasing attention as a way in which emerging nations can pursue digitization without requiring centralization because each layer of the stack may operate independently, with more or less direct involvement of the government.9x See a fuller description here, for example: Raman and Chen of CGAP (2017) on the implications of the India stack available at: www.cgap.org/blog/should-other-countries-build-their-own-india-stack. The concept of the stack is simple and appealing, offering the prospect of principles and protocols that can be applied across countries to achieve the same goal.

At present, there is no explicit recognition of ODR in the India stack, although there is a clear need for dispute resolution at all layers – for example, resolving a stolen identity or an inter-bank payment that is not completed. Each layer has some form of procedures for handling complaints or disputes; but there has not yet been a general vision for how ODR can be applied in a consistent way, relying on robust digital identities and potentially drawing on records of consumers, which they may consent to release for the purposes of adjudicating a dispute. The digital government ‘stack’ is another way in which the role of ODR can be situated as part of a wider government agenda.Figure 4: The Current Layers of the India Stack Source: Indiastack.org

Source: Indiastack.org -

5 Conclusion

This article has argued that the conditions for the large-scale application of ODR are ripe around the world including, or perhaps even especially, in emerging countries. This is because, although more people than ever before have Internet access and are buying online, the gap between providing effective recourse and the realities may be growing wider. Reframing ODR in the ways suggested here is one approach to ensuring that ODR is considered by policy makers, regulators and providers, as part of the solution set to narrow this gap. To be sure, reframing alone is insufficient: there is much work to be done to understand and then to develop the applications that can provide effective digital justice in the burgeoning array of new services. However, reframing now, at a relatively early stage, is at least a positive step to ensuring that ODR solutions are not simply retrospective add-ons. As they mature, new solutions quickly become harder to change: this is well illustrated in the reported experiences of trying to automate court processes that have existed for decades, if not centuries, in developed countries. But while developed countries may have been the proving grounds for ODR solutions to date, emerging markets will likely become the testing grounds on which the true relevance of ODR is tested in the years to come. The test will be how the applications of ODR can in fact narrow, or perhaps even close, the digital justice gap there.

-

1 K. Sodangi, ‘Country Experience: Nigeria’, ONC in ICT Ministry, paper delivered at Africa E-commerce Conference Nairobi, July 2018.

-

2 The same survey showed that 15%, almost 1 in 6, of goods bought are returned in Nigeria.

-

3 Available at: https://www.worldpay.com/global/insight/articles/2018-11/global-payments-report-2018.

-

4 OECD/G20, 2018, available at: https://www.gpfi.org/sites/default/files/documents/G20_OECD_Policy_Guidance_Financial_Consumer_Protection_Approaches_in_the_Digital_Age.pdf.

-

5 See FCA’s original call for input on regtech in 2015 available at: https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/call-for-input/regtech-call-for-input.pdf.

-

6 See http://vendors.r2accelerator.org/. It is possible that some of the 56 providers listed under consumer protection may offer ODR solutions but this is not indicated or highlighted separately.

-

7 See https://ispirt.in/.

-

8 See report in the Times of India, March 2018, available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/aadhaar-covers-over-89-population-alphons/articleshow/63202223.cms.

-

9 See a fuller description here, for example: Raman and Chen of CGAP (2017) on the implications of the India stack available at: www.cgap.org/blog/should-other-countries-build-their-own-india-stack.

International Journal of Online Dispute Resolution |

|

| Part II Private Justice | The Case for Reframing ODR in Emerging Economies |

| Keywords | ODR in emerging economies, regtech, India stack |

| Authors | David Porteous |

| DOI | 10.5553/IJODR/235250022018005102007 |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Abstract Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

David Porteous, "The Case for Reframing ODR in Emerging Economies", International Journal of Online Dispute Resolution, 1-2, (2018):61-68

|

Reports of ODR implementations in emerging economies are still rare, at least outside of China, which in many ways has already emerged digitally at least. But the lack of reports does not mean that there is not increasing ODR activity there. Underlying forces – the usage of smart phones and the rising volume of digital payments outside of the dispute frameworks created by traditional payment card schemes – point to increasing potential access to digital justice, as well as the need for it. This article argues for reframing the case for ODR in two ways that may make it more relevant for policy makers in developing countries. The first is to position ODR in the rapidly growing field of ‘regtech’ (regulatory technology). The second is to show ODR as a layer in the emerging ‘stacks’ of the technology enabling digital government, such as the ‘India stack.’ |