-

1 The Welcome

The first task of a conference is to welcome the participants and to inform them of the purpose of what they have been invited to. This task needs to be done in a culturally appropriate way. This particular conference took place in Southern California. Let us pick up the action as the facilitator seeks to engage the assembled group in the process.

John Winslade: Welcome everybody. We are here to hold what we call a restorative conference. And this is a meeting that is called when something has happened that has gone wrong at school. And the aim of this meeting is to help put things right after some kind of offence, some kind of problem, has come to the surface. Let me just give a couple of comments about the meeting today and then we’ll ask you to introduce yourselves. The meeting here is not like court hearing. We’re not here to establish who is right and who is wrong and I’m not a judge. In fact, it’s actually a meeting about restoring respect and trying to put things back to a situation where people can get on together okay in the school, which is what we want, so that learning can continue. So, I would ask that each of you respects the privacy of the other people who are here. Is that okay?

Several voices: Yes. Yeah.

John Winslade: Because we don’t want to just spread around to everybody the things you’ve said here in this room. I hope that’s okay with everybody. And the aim of this meeting is not to find out what happened, because we’ve already established that and Ms. Myers is going to speak to what she has found out. The aim of the meeting is to fix things and to make meanings and to sort things out. And Christina, my understanding is from what Ms. Myers has told me that, you’re willing to do that, you’re willing to try and fix things and to try make a meanings, is that fair?

Christina: Yeah.

John Winslade: That was why you’ve agreed to come to this meeting? There is going to time for everybody to speak, and so, I want you to be conscious of that and don’t feel like you have to interrupt when anyone else is speaking, because you will get your turn, your chance. My job is to make sure everybody gets a fair chance to talk. And the meeting could take an hour and a half, maybe even two hours sometimes. So, I appreciate you being willing to give some time for this purpose.

So far, the facilitator has done the following things: a) welcomed participants to the meeting, b) outlined the purpose of the meeting, c) sought commitment to the ethic of respect for privacy, d) indicated how long the meeting might be expected to take, and e) invited the offender to express a commitment to setting things right. All these things are done quickly and lightly without getting bogged down.

-

2 Introductions and Hopes

The facilitator continues with introductions to everybody present and asks each participant to express a hope for what the meeting will achieve.

I’m going to ask you to introduce yourselves. But first of all, let me say that my name is John Winslade and I’m a counsellor at the school here. So, what I’m going to ask you to do is to introduce yourselves and say one thing you hope will come from this meeting. It’s my sense that you’ve all come here with some hope that something would happen here. Maybe you would like to start.

Mr. Mitchell: I’m Mr. Mitchell. I’m a drama teacher here with both Delia and Christina and one thing that I hope to get out of this meeting is to rectify their friendship.

John Winslade: Okay. So, your hope is that this meeting will rectify the friendship?

Mr. Mitchell: Yes.

John Winslade: Okay. You are the next.

Delia: My name is Delia Lopez. I guess I came here because I want to know that I’m safe and I want things to go back to normal.

John Winslade: Okay. So, what you are hoping for is safety and things back to normal.

Livni Lopez: My name is Livni Lopez, Delia’s elder brother and legal guardian. And I’m here to see that something happens about what happened with my sister and Christina.

John Winslade: Something happens.

Livni Lopez: I want this to be rectified. So it never happens again.

John Winslade: Okay.

Ms. Vail: I’m Ms. Vail, Christina’s mother. And I need the situation to be over. This is like the third meeting I’ve come to school and I just need it to be done, so I can go back to work.

John Winslade: Okay. So your hope is that the situation will be over.

Christina: I’m Christina Vail and I guess I came here hoping that people wouldn’t see me as the bad person and I can have my say in the situation.

John Winslade: People wouldn’t see me as the bad person, right? And you’re also hoping to have your say in this situation. Okay.

Ms. Myers: My name Ms. Myers and I’m the Assistant Administrator here. And my hope is that these girls can learn to resolve problems in a non-violent way, peacefully and be respectful here in our campus.

John Winslade: Learn to resolve problems in a non-violent, peaceful way. Thank you.

Cambria: My name is Cambria Ruth. I’m friends with both Delia and Christina, and I just hope that they can resolve their friendship and stop all the drama.

John Winslade: So, resolve friendship and stop all the drama. Thank you, everybody.

One round has taken place and everybody present has had the chance to speak and simply state their name and make a brief statement of hope. The “round” format ensures that each participant’s contribution is equalized and no voice gets to dominate. Each statement is nevertheless different, according to the perspectives of the participants. Both the victim and the perpetrator have a chance to speak. The facilitator acknowledges each contribution and notes what each person says. The effect of hearing this series of statements of hope is that the purpose of the meeting is strongly aligned with a counterstory of forward movement. The next step is to outline the problem story.

-

3 The Problem Story

Now, it is time to address the problem that has led to the meeting. The facilitator invites the school administrator (or representative) to speak of the facts of the situation and of why the school takes it seriously. The facilitator then asks the offender and the victim whether they agree with the facts outlined. Next, the facilitator draws a circle on the white board and asks each participant to state briefly in their own words what they see as the problem. Each answer is written in the middle of the circle on the whiteboard. No answer is privileged as more truthful than any other. The facilitator uses the practice of externalizing (White, 1989, 2007; White and Epston, 1990; Winslade and Williams, 2012) and does not record the name of any person in the circle. Only actions are listed. The aim here is to create a separation between persons and problems in the hope that the perpetrator can step away from a close identification with the problem story.

John Winslade: What we need to do is, first of all, establish what happened and what has brought us to this meeting. I’m gonna ask Ms. Myers to speak to this, because Ms. Myers spoke to me and we actually made a decision that this meeting might be a helpful way to address things. So, can I ask you to speak to what happened, why the school took it so seriously and why we are all here?

Ms. Myers: Sure. Well, on Monday, October 5th, I guess there was an incident on Facebook. It was brought to my attention by Mr. Mitchell. He came to my office and he talked with me about some posts … that happened on Facebook. So, I did a thorough investigation and I talked with Christina and I talked with Delia. And Christina admitted to the posts … I don’t know if you want me to read them out.

John Winslade: Yes. Let’s hear them. I think it’s important that we know exactly what we’re dealing with.

Ms. Myers: On October 5th, there was a post by Christina, tagging Delia, saying someone should get in your face, no one likes you, you better watch your back tomorrow in drama, tomorrow might be the day and it might be me, and there was another post that said, oh and I know which way you walk home … I had a conversation with both girls, and then, also I talked with Mr. Lopez and I also talked with Ms. Vail.

John Winslade: So, can you speak to why the school thought it was serious enough that we call this conference here?

Ms. Myers: Sure. Well, obviously it’s really serious because this is affecting school; it’s affecting academics, even though this didn’t happen on campus; their argument in class is disrupting school activities; it’s affecting other students; they’re having problems in getting along. Also, this isn’t the first incident, because when I looked through Christina’s discipline record, there was another incident in the past recently this academic year, where she threw a stapler in a different classroom. There was another incident where she stormed out of the classroom. She has a few detentions for missing assignments, talking back to the teacher. There was another incident with starting rumors about another girl. She has a few truancies, so this isn’t the first incident and that’s why it’s really concerning to me, because this is something that’s repetitive and ongoing.

John Winslade: And this particular series of messages on Facebook, did you take this to be more than just messages… it’s some kind of threat, is that right? I mean it sounded to me like a threat. I’m just wondering, was that how the school thought of it?

Ms. Myers: Yeah, definitely. These aren’t just minor posts. These posts definitely sound threatening. It sounds like harassment. It sounds like bullying. It sounds like she is directly threatening her, because Christina tagged Delia’s name in the post. And she also threatened that it might be in drama. So, that’s not acceptable, we can’t have violence and threats and bullying and harassment happening in our school.

John Winslade: Okay. So, the school has taken this seriously?

Ms. Myers: Very much.

John Winslade: So Christina, can I ask you, you’ve heard what Ms. Myers read out. Does that sound accurate, because we did talk about this before the meeting. I just want to check this with you.

Christina: Yeah, it sounds accurate.

John Winslade: So you acknowledge that this is what did happen? Okay. And Delia, can I just check with you. Does this sound accurate to you as well? (Delia agrees.)

John Winslade: All right. Thank you both, because that helps us to go ahead. We’re not arguing about what happened. We’re here to actually put it right. I’m now going to ask you each to think about what you’ve heard … and your own perspective on the problem. I’m gonna ask you to tell me in a few words what you would call the problem that happened and what we are here to deal with. And I’m going to write what everybody says and put it on the white board up here. So, I’m gonna ask one person to volunteer to start. And then we’re gonna go around the circle from there. Okay, so what you would call from your perspective this problem that we’re here to deal with?

Delia: I’d say it was a threat.

John Winslade: Thank you, Delia? (Writes “a threat” in the circle on the whiteboard.)

Livni Lopez: I’d say that it’s an act of violence, a severe act of violence.

John Winslade: Severe act of violence, yes. (Writes “severe act of violence” in the circle on the whiteboard.) Thank you. What would you call it, Mr. Mitchell?

Mr. Mitchell: Knowing the two girls, I’d say it was an outburst, played to the extreme, an emotional outburst.

John Winslade: An emotional outburst. (Writes “an emotional outburst” on the whiteboard.) Cambria, what would you say?

Cambria: I would call it a misunderstanding.

John Winslade: Misunderstanding. (Writes “a misunderstanding” on the whiteboard.) Ms. Myers?

Ms. Myers: I would say unsafe, disrespectful.

John Winslade: Unsafe what?

Ms. Myers: Unsafe problem-solving or unsafe response or unsafe interaction.

John Winslade: Unsafe interaction, can we stick to that? (Writes “unsafe interaction” on the whiteboard.) What you would call it Christina?

Christina: I would say it was just kind of teasing … simple teasing.

John Winslade: Simple teasing, thank you. (Writes “simple teasing” on the whiteboard.) Ms. Vail?

Ms. Vail: I was thinking – I’m trying to think of clean language for it – almost like Facebook ridiculousness, because I feel like this is always going on with all of them on Facebook.

John Winslade: So, Facebook ridiculousness. (Writes “Facebook ridiculousness” on the whiteboard.) … So, there are a lot of different names for this problem, reflecting each of the different perspectives that you bring to this meeting. And I’m not here to say which one is the correct name; in fact, the problem we’re here to do with includes all of this.

-

4 Mapping the Effects of the Problem

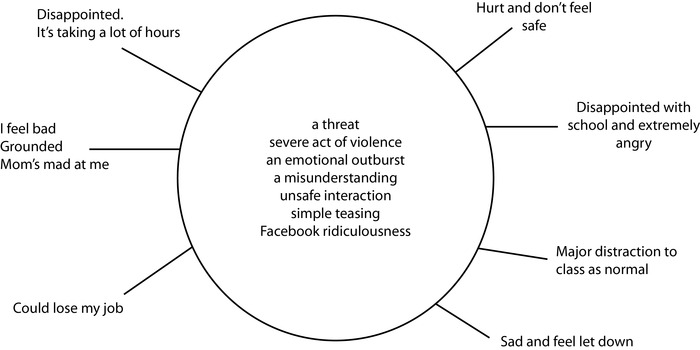

The facilitator now turns to mapping the effects of the problem on each person present. He draws spokes out from the circle (see Figure 1) in which he has written everyone’s names for the problem story, and at the end of each person’s contribution, he writes beside one of the spokes in a few words what they have said about how the problem has affected them. This process continues until each person has spoken. It is important that the facilitator asks the victim early in this process so that this person’s voice is privileged in a way that it often is not in a retributive approach. It is also important that the perpetrator is asked how the problem is affecting her. Doing so begins the process of breaking down the categorization of people as solely victims or solely perpetrators.

John Winslade: So, I want to ask you another question and go around the circle again. I’m gonna start with Delia, because you’re the person who is most directly affected. And the question is, what effect has all of this that happened had on you personally? Delia, it most directly affected you, what would you say the effect of it all was for you?

Delia: Well, overall, this entire situation has just been hurtful. I lost my best friend. I don’t feel safe walking home anymore. Like I’m hurt.

John Winslade: Hurt and don’t feel safe. (He writes these words on the whiteboard at the end of one of the spokes.)

John Winslade: … Okay. Mr. Lopez, what would you say? …

Livni Lopez: I was extremely angry. I was extremely disappointed with the school with the behaviour of the students. It kills me to see Delia in so much pain.

John Winslade: Disappointed with the school and extremely angry? (He writes these words on the whiteboard at the end of one of the spokes.)

Livni Lopez: Yes.

John Winslade: All right. Mr. Mitchell, what would you say the effect of all of this was for you?

Mr. Mitchell: It’s concerning. A major distraction as we were preparing for the Fall show. It was hard to continue to carry on classes as normal, knowing that some of my students were having some conflict.

John Winslade: Right, okay. So, major distraction to class as normal. (He writes these words on the whiteboard at the end of one of the spokes.)

Mr. Mitchell: Yes.

John Winslade: Cambria, what effect has all of this had for you?

Cambria: Well, I would say, it just makes me really sad. I came to the school last year, second semester, because in my high school, there was a lot of gossip and stuff, and I was told that it would be a safer environment here and I feel I have kind of been let down with all the drama.

John Winslade: So, it makes you sad, and it feels like you’ve been let down with your hopes for coming to the school, right? (He writes these words on the whiteboard at the end of one of the spokes.)

Cambria: Yeah.

John Winslade: Okay. Ms. Myers, what effect did that all have for you?

Ms. Myers: I’m really disappointed … in the posts. I’m disappointed in the past behaviour. I’m disappointed that these two girls are at this place at this point. And also, this is very exhausting too, because it’s very time consuming and has taken a lot of hours out of my day, listening to them and talking with the girls and their parents.

John Winslade: So, it’s taking a lot of hours for you. (He writes these words on the whiteboard at the end of one of the spokes.) Okay. Christina, what effect is all of this having for you?

Christina: I feel bad that people see me this way and my friend sees me this way. I guess I was just trying to stand up for myself and everyone’s taking it as such a bad thing.

Ms. Vail: You’re grounded.

John Winslade: Is that having effects as well for you being grounded?

Christina: Oh, yeah. My mom is being mad at me.

John Winslade: Mom’s mad at me. (He writes these words on the whiteboard at the end of one of the spokes.)

John Winslade: What effects does it have on you, Ms. Vail?

Ms. Vail: Well, I’m gonna lose my job if I take any more time off for these meetings. I already had one warning at work. And God knows what’s going to happen if I lose my job?

John Winslade: Could lose my job. (He writes these words on the whiteboard at the end of one of the spokes.)

The problem story

-

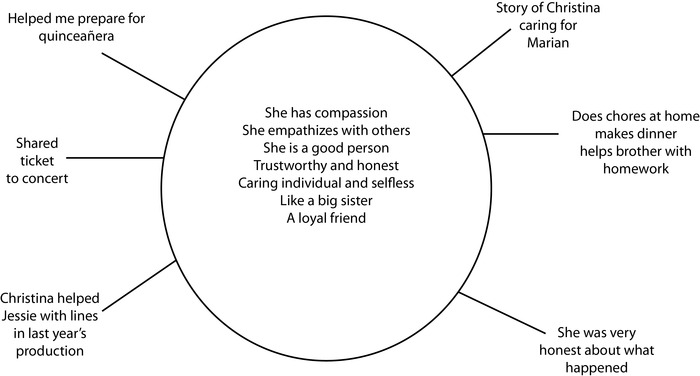

5 The Counter Story

Having now documented the problem story on the whiteboard, the facilitator now moves to do the same for the counterstory. He draws a second circle alongside the first one with spokes coming from it. This time, he works from the outside in, and starts with the spokes on the outside of the circle. The assumption here is that everyone’s life is made up of multiple stories (White, 2007). No one can be represented by a single totalizing story. It does not diminish the truth of a problem story to also acknowledge that a story of contrast also exists. The facilitator therefore intentionally asks for anyone who can recall an instance of the offender acting in a way that does not fit with the problem story or would not be predicted by it. This question is opened up to the whole group, and by now, it is not necessary to use a round format. Each story that is told is summarized on one of the spokes around the second circle and the facilitator asks, “What does that tell us about [the offender]?” The answers that are given amount to personal qualities or values. The facilitator writes these in the middle of the second circle.

John Winslade: Okay. So, all of this is the problem we here to deal with. I’ve got another circle over here. And as we can see this problem is actually affecting many people in one way or another. But my guess is that it doesn’t ever tell the full story. This is the problem that we’re here to deal with, but if we only pay attention to this problem, we might be blind to some other things that we need to also take account of. Because my guess is this doesn’t tell us all we might need to know about Christina, for example. So, what I want to ask you is that, if you were to think about anything that each of you could tell me about Christina. I’m just gonna throw this open, I’m not gonna go around the circle this time. One thing you could tell me that does not fit with this story and with its effects…

Cambria: I have something, this really surprises me, because last month, Marian and her parents, they started going through divorce and it was really hard on her.

John Winslade: Hard on Marian, you mean?

Cambria: Yeah, it’s hard on my friend, Marian. And she doesn’t really have any really close friends, and so, Christina stepped in, Christina was there. Christina let her stay at her house. And they’re not very close, but she just helped her, because she was trying to empathize with what she was going through and Marian stayed at her house for a few weeks and she was really compassionate and I don’t know somebody like this that could do this … she was very helpful.

John Winslade: … And Cambria, you told me what happened … what would you say this tells us about Christina if we think about what she did then that does not fit with this story, what does that say about her?

Cambria: Well, she definitely has some compassion in her and she definitely tries to empathize with others.

John Winslade: Okay. She has compassion, she empathizes with others. [He writes this in the middle of the circle.] And I’m not saying that this makes any of this [points to diagram of problem story] not true, but this is just also a part of a different story that we also need to take account of. Who else can tell me anything you know about Christina that doesn’t fit with the story over here?

Ms. Vail: I didn’t raise her to be like this. I raised her to be kind towards others and truthful and not get involved in a bunch of junk like this.

John Winslade: Okay. So can you give me an example of how she has shown in her actions that you raised her to be kind and concerned about others and truthful. Tell me one story, one example that would help us understand that about Christina.

Ms. Vail: Well, like she does a lot of chores at home. Not just when she is grounded, but sometimes, she’ll like do the dishes or if I’m going to be late at work, she’ll make dinner for us and be more of that kind of person.

John Winslade: Okay, anything else to add to this?

Ms. Vail: I guess just stuff like she will help her brother do homework, and yeah, that’s all I can think of, that I remember.

John Winslade: So, when you think about Christina, helping her brother’s homework, helping you out with things at home, doing the dishes, making dinner for everybody, [The facilitator writes these on the whiteboard] what does that say about Christina, if you can think about what that means?

Ms. Vail: Like, she is a good person. [The facilitator writes this in the centre of the circle.]

John Winslade: Okay. Anybody else?

Ms. Myers: One thing I noticed about Christina is that during our conversation, she was really honest about everything. Because most of the time, you know, the students will lie and I have to spend several hours getting witness statements and talking with some others. We didn’t have to do much of that because she was very honest. [The facilitator summarizes this information on the whiteboard.]

John Winslade: Okay. What does that tell you about her?

Ms. Myers: That’s something like I can trust her…

John Winslade: Trustworthy, right. [The facilitator writes “trustworthy and honest” in the middle of the circle.] What else? Anyone else?

Mr. Mitchell: When I think back to last year, she was helping out a former classmate, Jessie, who was struggling to just pin down her lines for the performance. And Christina, being one of my top students, just jumped in and aided her when she didn’t need to, spending countless class hours after school and helped Jessie do a really good job in that production.

John Winslade: Okay. [The facilitator summarizes the story of Jessie on one of the spokes around the circle.] And what does that suggest to you about Christina that she did this for Jessie?

The counterstory

Mr. Mitchell: She is a caring individual. Selfless.

John Winslade: Caring individual and selfless. [The facilitator writes these words in the centre of the circle.] Delia, my understanding is you two have known each other for quite a while, right? [Delia agrees.] Is there anything that you know about Christina that doesn’t fit with this story here that has been such a problem for you.

Delia: Actually, this entire thing was a bit of a surprise. Christina and I have been friends since eighth grade. And she helped me a lot during my quinceañera, during my 15th birthday. She was never late for any of the practices. She helped me pick out my dress.

John Winslade: Okay. So you’ve known her for eight years and she helped you during your quinceañera. So, when you say it was a surprise almost for you, all this problem that happened, this is like you knew her as a different person before this. And how would you say that you knew her? What does that say about Christina?

Delia: Christina is always been like a big sister to me. She is really helpful and I knew that I could always count on her when I was going through anything.

John Winslade: Okay. [The facilitator writes “like a big sister” inside the circle on the whiteboard.] Thank you everybody.

Livni Lopez: Let me add.

John Winslade: Yes.

Livni Lopez: Because, what she said about being shocked, I shared the same feeling on the way here as we were talking in the car. I was still in disbelief. I was really, really upset, because what I’ve known from Christina is that, because that one time that she won tickets to a concert, and Delia didn’t even think that she was going to pick her. All of a sudden, she came and said, I want to take you to the concert and I know how happy Delia was. So, she seemed like she would be a very loyal friend.

John Winslade: So, she shared a ticket to a concert [The facilitator writes this on one of the spokes around the circle] and what that shows you about is that she can be very much a loyal friend. Is that fair enough?

Livni Lopez: Yes.

John Winslade: Thank you. [The facilitator writes “loyal friend” inside the circle.]

-

6 The Challenge

Now that there are two stories represented on the whiteboard, the facilitator turns to the “offender” and asks her to indicate which story she would prefer others to know about her in future. All the offender has to do is to indicate which story she would prefer. By choosing, she takes a small step into the counterstory. This step in the process may only occupy a small window of time, but it is decisive and pivotal. All that has gone before has led up to it and all that follows leads from it.

John Winslade: So, we’ve got two stories and I’m not saying either one is the only story or the true story. They both have truth about them. Christina, I’m gonna ask you something. If you look at both of these two stories, this one here [indicates Figure 1] which is a problem that we’re here to deal with and these other things [indicates Figure 2] that people know about you that don’t fit with that problem. Which one in future would you like to be the story that everybody knows about you that goes forward from this meeting?

Christina: The right one [points to Figure 2].

John Winslade: This one here? Thank you. Okay. Can I ask you to say why?

Christina: That just seems like that’s how people see me and that’s a good thing. If I was the left one, I wouldn’t really like myself, if people saw me that way.

John Winslade: Right. So, you don’t want people to see you this way, because it would lead you to not like yourself, right. And you much more would like people to see you in this way, right? Thank you.

-

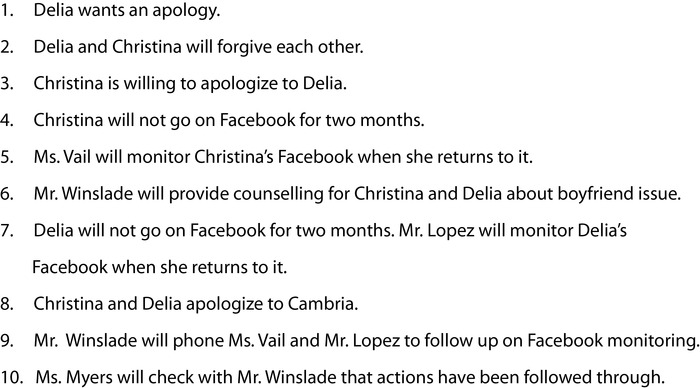

7 Growing the Counter Story

The next stage of the process is about growing the counterstory. The facilitator starts with the victim and asks her to speak about what she would need, if the problem story is not to continue to have effects on her. Her family members and any supporters are asked a similar question. Then, the facilitator asks the offender what she is prepared to offer. A negotiation then takes place about these ideas. Others are also asked how they can support the growth of the counterstory, including parents and teachers. In other words, the facilitator resists any expectation that the offender should be isolated with the task of taking responsibility. He asks everyone to participate in this effort. Gradually, the participants contribute to the plan and establish a “community of care” around the offender and the victim.

John Winslade: So, that leaves us with the need to work out how we can get this story to be the one that goes forward [indicates Figure 2], and for this story to be just dealt with [indicates Figure 1], so that it doesn’t actually go forward from this meeting, it doesn’t continue, right. That’s our purpose here. What I’m gonna ask is for any thoughts that any of you have about what would help this story to be the future story about Christina, particularly in relation to Delia. And I’m gonna start with you, Delia, because you are the person who is most directly affected. I’m gonna also ask you Mr Lopez to speak to this as well. What do you need, Delia, to make sure that this problem story goes away and this story here is the one that you have a chance to know about Christina? What do you think?

Delia: Okay. Well, for me, a big thing is just apologizing. You haven’t given me a single hint that you are sorry for this. You just put our friendship on the line, like it didn’t matter. [Delia is addressing Christina directly.]

John Winslade: So, for you, one thing you would need would be an apology, right?

Delia: Right.

Livni Lopez: I’m sorry. It’s critical, but how we will know it’s not going to happen again. Saying apologies and all is great, but how can we be sure that Delia is going to be safe and this is not going to happen again?

John Winslade: Okay. That’s an important question, right. And maybe either of you would have any ideas like what will help you to feel safe. I don’t know at this moment, whether Christina is willing to offer an apology, either. We have to wait and give her a chance that to respond to that. But I’m hearing you would like something a little more than an apology? And … you would like to know it’s not going to happen again?

Livni Lopez: Absolutely. Right.

John Winslade: What do you think would give you that security or that assurance?

Livni Lopez: At this point, I’m not sure. It frightens me that this happened through Facebook. So, I don’t know if it’s something with having to monitor that, the Facebook posts … or having the teachers or the counsellors involved with this.

John Winslade: So, that’s one idea that you might come up with, some kind of monitoring, is that right?

Livni Lopez: Yes.

John Winslade: Delia, you want to speak to this? What would give you a sense of security that your brother is speaking about that this is not going to happen again?

Delia: I think monitoring Facebook would be fine, but when Christina and I were as close as we were, she wasn’t like this. There was no chance she was going to hurt me. And I feel like if we go back there and we fix that, I will feel safe enough.

John Winslade: Okay. If things were to go back, in terms of your friendship, to where they were, right? What would need to happen for you in order to return to that place?

Delia: Well, to know that I forgive her and she forgives me. I know that we’ve had problems and stuff. But it’s not worth losing our friendship.

John Winslade: Okay. So, forgiveness might help. But that’s something that people have to choose to offer. You may both have to choose whether you are willing to offer that.

-

8 Apologies

A note about apologies is worthy of mention. It is common in this process for apologies to be offered or asked for. However, participants, as happens here, often voice a concern about how much an apology can be trusted. The facilitator responds by taking up a narrative perspective on apologies (see Winslade and Williams, 2012) in which it is important to treat the apology, not as the end of a problem narrative, but as the start of a counternarrative. Therefore, when someone makes an apology, the facilitator responds to it as an event on the landscape of meaning (Bruner, 1986; White, 2007) that also needs to be followed up with events on the landscape of action. The facilitator thus asks what the spirit of the apology can lead to, or what the person who receives the apology might need to happen to be convinced that the apology is sincere and can be trusted. Notice here that the value of an apology does not rest on the strength of feeling behind it, but on the actions that it leads to.

John Winslade: And Christina, I want to invite you to speak to this point. Do you have any ideas about what’s going to make this story [points to Figure 2] the one that’s known more about you … rather than this problem story [points to Figure 1]. What do you think would help you to restore things back to where things used to be.

Christina: I guess, I would be willing to apologize to Delia, if she would be willing to apologize to me for making me do what I did and everything. It’s just been a lot of drama, and we started drifting, because she stole my boyfriend, who I was going out with for like almost five months. And she started talking to him without me knowing about it. And I guess I was just really mad at her for doing that, because I trusted her. But I would be willing to apologize, because I don’t think that’s something that I want to lose a friendship over.

John Winslade: So, the friendship is important to you too, right. And that’s more important than other things that would interfere with losing that friendship. Is that fair? (Christina agrees.) Okay. So for that purpose, you’re willing to apologize. For what exactly, Christina?

Christina: For writing some stuff to her on Facebook that could be taken badly.

John Winslade: Okay. Do you want to do that now or what would be a way for that to happen, like does it have to be spoken or written or witnessed or what do you think, either of you?

Delia: I think saying it, like getting it in the air, I’m sorry and I’m honestly okay, again.

Christina: I’m sorry too, for writing that stuff. I wouldn’t hurt you.

John Winslade: Okay. And you had a question about whether you can trust this, right?

Livni Lopez: Yes.

John Winslade: And I want to come back to that question for you, Christina. If you’re willing to give that apology, how might you show Delia that you are sincere in making that apology? What would you say? How would you show it and perhaps so that she could trust it, so Mr Lopez can actually understand that this is not going to happen again.

Christina: I guess there is no way unless you both trust me, but I would be willing to apologize to you and your whole family if that is necessary and I would just stop maybe going on Facebook for a while just to get away from all of that.

John Winslade: How does that sound?

Mr. Lopez: That sounds much better.

John Winslade: Why does that help, Mr Lopez? What’s helpful about it?

Livni Lopez: Because Facebook was what she used.

John Winslade: So, how long would you need to know that she was to carry through with her intention there. How long would you say that she needs to do that before you could feel like she was sincere in the apology?

Livni Lopez: Part of me says through the rest of the year, school year, now it’s just started. But knowing that Facebook is really popular, I think a couple of months … And even afterwards, maybe if Ms. Vail can keep track of that afterwards, I think that would be ideal.

John Winslade: So, there is a proposal, how’s that sound to you? Does that fit with what you are offering?

Christina: If that’s what it will take to be able to have my friendship.

Ms. Vail: Yeah. And I’m going to be monitoring that.

John Winslade: And you are asking also that Ms. Vail has a part in monitoring that?

Livni Lopez: Yes.

Ms. Vail: I mean, I can watch her Facebook and I know she took it to a new level here, but they go back and forth on Facebook all the time. So, I know she took it to a new level, I admit that. I’m just saying they go back and forth. I’m willing to monitor that. If she’ll let me look at her Facebook, I’ll look at her Facebook.

John Winslade: You’re willing to monitor it. Ms. Myers, just on that point, how would the school know that this is happening so that … the school could trust that this is actually changing and dealing with the situation.

Ms. Myers: I’m wondering if maybe these girls need counselling, because it sounds like they were surprised that these things were major incidents, and that it was harassment and bullying and it was really, really serious. So, I wonder if maybe we could set them up with counselling, and then, they can learn some friendship skills.

John Winslade: Well, it sounds like this is a particular issue, that has arisen between you, that comes to light as we’re talking about this … right? Because you said you would like something from Delia as well … Will you speak to that again?

Christina: I’m just worried about the apology that she gave me. I guess maybe if we were both just stop going around Facebook to kind of see, to kind of not be caught up in that drama and to know that she is not going to behind my back talking about me …

John Winslade: So, that would be important to you that it’s not just happening … in reverse to you. Delia is not doing the same kind of thing on Facebook to you. What would you say to that, Delia?

Delia: I think that’s fine. I’m willing to give up Facebook like she is for me.

John Winslade: Okay. You also mentioned the issue of your boyfriend, your former boyfriend.

Christina: No, it’s her boyfriend.

John Winslade: It’s her boyfriend. I would … be willing to offer that we actually have a conversation, the two of you together with me and we try and address that issue and that’s the kind of thing that you were asking for … some counselling.

Ms. Myers: You are right.

John Winslade: Are you two willing to be part of that and try and sort that out?

Christina & Delia: Yeah, sure.

John Winslade: Alright. Now, you were wondering about how this monitoring of Facebook might happen. That’s your suggestion, Mr. Lopez, that’s right?

Mr. Lopez: Yes.

John Winslade: Are you happy with what we’ve talked about the way that’s going to happen or is there anything else that you think needs to happen?

Mr. Lopez: Just like Ms. Vail, I’m willing to also take a proactive stance on monitoring her Facebook when she does go back on it.

John Winslade: So, you guys will monitor each of their Facebook posts, right? And can I may be check with you after maybe the first couple of weeks, and then, again after a couple of months to see that it has been happening. Is that okay if I give you a call and have a phone conversation, rather than come in for another meeting?

Ms. Vail: Okay, thank you. Sure.

John Winslade: Is that okay if I ask you on the phone as well?

Livni Lopez: That’s fine.

John Winslade: What about you, Mr. Mitchell, or Cambria? Anything else that you would like to see?

Mr. Mitchell: Counselling is something that I would like to see because I didn’t see that there was anything that I could facilitate in my classroom that would rectify the friendship. There was just an awesome presence between the two of them on stage and I want to get back to that.

John Winslade: You want to get back to that. Any thoughts about what would be necessary to get back to that presence on stage?

Mr. Mitchell: I believe the counselling. The two of them sitting down with you.

John Winslade: Is getting back to how things were so you can do your best on stage important to both of you? … You’re both nodding. So, maybe that’s part of what we will talk about when we meet together too. Anything else … Cambria … you would like to see happening?

Cambria: Well, I think it’s really important that they do apologize to each other and I think they should both apologize and I think that they should kind of watch how they act to each other at school. Because since what Cristiana initially did in October on Facebook, since it was on Delia’s wall, it was public, so many of our classmates kind of started talking about it. And so, I think it’s really important to be respectful of each other in public, and just cause the person isn’t there doesn’t mean that you should be able to gossip about them behind their back. So, you should know that.

John Winslade: So, this has actually affected other people? … And you’re the person who is representing the other people here today.

Cambria: Yeah. Well, because I was getting to be really close friends of both of them. So, I was new to the school and they were both really nice to me and I started doing theatre and … all of a sudden, over the summer, they just… I just don’t know what happened. I don’t like it.

John Winslade: So, this whole thing has put you in a difficult place in relation to two friends, right?

Cambria: Yeah. But then, the night that it happened, Delia called me up and she was crying. She told me what happened and I said who did it and she said Christina did it, and then, I kind of didn’t really want to betray one of them, and so, I didn’t feel like I could talk to Christina, because then I was betraying Delia, and then, vice versa with Delia. So, it’s kinda ruined my friendships, really, with both of them.

John Winslade: Christina and Delia, any response you want to make to what Cambria is just saying?

Delia: I didn’t know this situation was affecting other people. I’m so sorry for that. It wasn’t my intention to, like, hurt our friendship.

Christina: I am sorry Cambria. I didn’t know that it was, like, affecting you or even my teacher, like my most trusted teacher and other people. I didn’t think that it would damage that much …

John Winslade: Okay. Thank you, everybody. And I appreciate, Cambria, this is not something that has not directly involved you or a member of your family, like everybody else here. And you’ve been willing to come along as a friend to both of these people. So, thank you for doing that.

Cambria: Sure.

John Winslade: Ms. Myers, if all these things happen, I think we’ve got a plan here [see Figure 3] with everyone, is that right? Anybody have any problems with the plan? So, Ms. Myers, if this all happens [indicates Figure 3], how does that meet requirements of the school for this issue being dealt with, because that was the reason, then, we called the meeting.

Ms. Myers: Well, if those things happen and we can resolve this in a peaceful way and the girls agree to follow through with what … you know, the plan, then we can move on. But if, you know, these things continue, then, I mean, this behaviour can result in someone getting suspended or even expelled.

John Winslade: So, you’re wanting to see this happens, so it doesn’t get to that level.

Ms. Myers: Yeah. I’d hate to see someone get suspended or expelled from the school. They are good girls, and I want them to stay at our school and be peaceful and get on well and get back to things.

The plan

-

9 Monitoring and Review

Once a plan for future action has been developed, it becomes necessary for a process of review to be established to ensure that it goes according to plan. This review need not involve everyone at the conference. The meeting can delegate it to a few people. A narrative perspective would lead us to expect that a review would not just be like a probationary meeting in which the extent to which people have done what they said they would do is checked. It is also an opportunity to listen out for unique outcomes (White, 2007). There will always be things that happen that are not expected, moments of creativity or surprise, or pieces of difference. An astute response to these moments would entail being curious about them in a way that weaves them into the counterstory, rather than leaving them in an isolated, unconnected space.

John Winslade: Okay. Well, thank you, everybody. I think we are nearly done here. And what I can see here is that we have a plan for what’s gonna happen. And my invitation to everybody is to make sure that this plan happens. And I see that I have a role to help to make sure that it happens. And the two parents … guardians, I should say … have a role to make sure that it happens. And Delia and Christina, you have a role to make sure that this happens. And Mr. Mitchell is trying to pay attention to seeing that it happens on stage and in drama, right? And Cambria, you have a role to also be conscious of what’s happening and to support the change this story being one that other people need to know about, right? Then, maybe anyone else who wants to see the drama continue, gets to know that you people have decided that it’s going to stop. And so, I’m going to undertake to check in with you as I said, to make sure that these things are shifting and changing. I would also caution that, given what’s happened, it’s not necessarily going to be instant that you two are best friends again. It’s gonna take a little bit of time and a little bit of work. And I’m willing to talk with you through that work, but I really appreciate the fact that you are committing yourselves to doing so. And Ms. Myers, I will communicate with you to make sure that we’re still saying that in a month’s time, and again, in two months’ time, this is still working towards the resolution that we have talked about. So, thank you, everybody. Would anybody like to comment on what we’ve done here today and how it has been for everybody?

Mr. Mitchell: It’s been good to see, I mean, given that genuine apology between the two of them, it’s very exciting to see that.

John Winslade: That makes a difference for you to see that?

Mr. Mitchell: Yeah. I think I’m impressed to see them look at each other.

John Winslade: Anybody else?

Christina: It’s been really helpful definitely, because I wouldn’t have been able to say what I have to say if it wasn’t for this meeting.

John Winslade: Okay. Thank you.

Livni Lopez: I still feel little bit upset. And I feel much better that things are being done about it. Now, we have the space that we can discuss this.

John Winslade: Yeah. So, feelings of being upset don’t just disappear immediately. They disappear as people show that they are willing to make all those things happen [indicates Table 3], right? So, I understand when you say you still feel a bit upset. Maybe others do as well. Anybody else got any comments about what we’ve done here today?

Ms Myers: I’m happy that we can do this instead of, you know, instead of someone getting suspended … I hope I won’t see you two in my office. At least, not for a problem …

John Winslade: Yeah, okay. Well, thank you and I’ll see you again very shortly, in fact, I’ll give you two an appointment before we leave. Just stay back and we’ll make a time when everybody else is on their way, okay? Thank you, Ms. Vail, for coming in. Thank you, Mr. Lopez, for coming in. And thank you for staying after school. And thank you, girls, for your willingness to address the situation, which is so important to each of you. And I know it’s not finished, but you’ve … taken a great step forward in dealing with it today. Thanks.

At this point, the restorative conference itself comes to an end. What has the process achieved? First of all, a fuller understanding of the issues has emerged. It was not just a piece of cyberbullying, although that was an important aspect. It was also a dispute over boyfriend relationships and its effects were widespread and impacted on a number of people.

Second, the situation has been dealt with without the school resorting to punishments. The stand-down from using Facebook by Christina and Delia has been supported by them and was actually suggested by their respective guardians. Buy-in is thus more likely, and follow-through more probable. It can easily be argued that attending such a meeting and following through on the plan is more demanding than any punishment likely to be given and requires considerable emotional commitment from the central participants. It is more specifically targeted at the kind of change that enhances relationships in and with the school too, without running unnecessary risks of alienation and resentment. Punishment (for example, suspension), by contrast, is less specific and more hit-and-miss in producing learning outcomes.

Third, the responsibility for addressing the situation is shared among a number of people. The offender is not isolated individually, but is intentionally supported to take up greater responsibility. This approach shows respect for her membership of a network and demonstrates to her that others in this network are also committed to addressing the situation, rather than blaming her personally for her lack of responsibility.

Fourth, this process gives a school counsellor the chance to participate in a disciplinary process without risking a role conflict with other counselling functions. The role of facilitator in this process is a skilled one, but it can be learned. The skills consist mainly in the asking of particular questions. This article has sought to illustrate these questions and the sequence in which they might be asked. Many school counsellors have shown in practice that they can learn these questions and facilitate this kind of process effectively.

Fifth, the process has drawn explicitly on principles drawn from a narrative approach to conflict resolution. A process of externalizing is used and the effects of the externalized problem are traced before a counterstory is constructed. Competing stories are recognized, and neither the offender nor the victim are totalized by any single story. Instead, the process values complexity but still invites the protagonists to make moral choices for the future.

Sixth, the immediacy of the process shown here does not indicate anything about the stability of what is achieved. Anecdotal evidence, however, suggests that the process does lead to effects that are not quickly forgotten. The fact that the event brings together a number of people who are able to serve as witnesses to a shift strengthens the outcome. Witnessing does, it seems, impact the viability of such a counterstory.

Finally, this process can be seen to be restorative, because it restores relationships between people that were damaged by the conflict, rather than dividing people into identity categories as winners and losers, good students and bad students, or victims and offenders. At the end of the meeting, a community of care around an issue is more intact than it was at the start. To be sure, it has taken an investment of time by the school. I would suggest, however, that this investment is worth making, because a potential festering problem has been addressed and future outbreaks of animosity are less likely (outbreaks that have the potential to cost more time as the same issues arise repeatedly). Young people have also potentially learned something about what makes relationships work, not just efficiently but also effectively. They are given the chance to learn something about being citizens in the process. Bibliography Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

The Restorative Practices Development Team (Helen Adams, Kathy Cronin-Lampe, Ron Cronin-Lampe, Wendy Drewery, Kerry Jenner, Angus MacFarlane, Donald McMenamin, Brian Prestidge, & John Winslade). (2004). Restorative practices for schools: A resource. Hamilton: University of Waikato.

Vail, L. & Winslade, J. (2013). Managing conflict in schools: A new approach to a disciplinary offense. Hanover, MA: MicroTraining Associates.

White, M. (1989). The externalizing of the problem and the re-authoring of lives and relationships. Dulwich Centre Newsletter [Special edition, Summer 1988-1989], 3-21.

White, M. (2007). Maps of narrative practice. New York, NY: Norton.

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York, NY: Norton.

Winslade, J. & Williams, M. (2012). Safe and peaceful schools: Addressing conflict & eliminating violence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

-

1 Used with permission.

The case study that features in this article is a transcribed role play of a restorative conference in a school after an offence has taken place. It is commercially available for streaming as a video (Vail and Winslade, 2013), produced by MicroTraining Associates and distributed by Alexander St Press (at the following URL: <http://search.alexanderstreet.com.libproxy.lib.csusb.edu/view/work/23640221>1x Used with permission. ). A transcript of this role play is used here to illustrate the facilitation of a restorative conference in a narrative mode. Restorative conferences have been written about before (for example, Winslade and Williams, 2012), but in this article, the emphasis is on showing the process in action. Around the transcribed role play (which is edited for space reasons), I have inserted commentary that makes clear what is happening and the purposes behind it. Overall, the purpose of such a conference is to find a way forward in a conflict situation – in this case, a conflict that is implied in the committing of an offence. The conference aims to resolve this conflict through convening a community of care around the offence and inviting everybody present to exercise responsibility for addressing the situation.

This process was developed by the restorative practices team at the University of Waikato (The Restorative Practices Development Team, 2004) and was based on the concept of the family group conference in the youth justice field. The process amounts to an alternative to punishment (such as suspension), but makes no claim to being a panacea that is applicable in every situation.

The transcript begins at the start of the conference, but already, much work has been done to set up the event. Conversations have been held with both parties and their parents and the story of what happened has been established. Moreover, such a conference cannot take place unless the offender has already admitted the offence. Therefore, the focus can remain on setting things right, rather than resembling a trial to establish guilt. Seats are arranged in a circle to emphasize equal participation by all and to encourage conversation. However, the facilitator carefully structures the conversation so that it does not promote conflict.