-

1 Introduction

From its early origins, peace studies has advocated a trans-disciplinary approach to scholarship, a normative orientation to purpose and a practice-relevant unde rstanding of knowledge. These three interwoven commitments have not always found an easy or comfortable expression, whether in local non-governmental organizations who seek to incorporate solid empirical evidence into their work or for an academic department that wished to provide cutting-edge research with relevance to concrete policy or practice-related challenges in settings of deep-rooted conflict. Within this tradition, as pointed out by Anthony Bing, the task of peace studies required the capacity to think our way into new forms of action and to act our way into new forms of thinking (Bing, 1989).

Looking back, we find a dynamic connection between social activism and engaged scientific study around significant local to global challenges. From Gandhi to King, from engaged seminary students in Nashville to doctoral programmes at Harvard and from practical trainings of the Highlander Folk School to the early development of the Bradford University’s first established programme, leaders mixed their work with commitments to university-based peace studies. In very distinct environments of higher education, the trans-disciplinary teaching of non-violence and conflict resolution as theory and technique, and as religious and philosophical commitment, thrived. To this was added the explosion of research and teaching in international relations, as well as even deeper analysis and teaching of the politics, sociology and psychology of non-violent direct action, which ultimately found a home in the multidisciplinary study of peace.

Over the past four decades, graduate and undergraduate programmes grew and became more embedded in the life and discourse of university education. The larger programmes with more faculty and well-financed research were able to engage fully the challenges of violence and injustice of the late-20th century. But in the world following 11 September, in particular, it became clearer that these three interwoven commitments – action–research–education – have not always found an easy or comfortable expression. This was true whether the focus was in the work of think tanks, non-governmental organizations or these growing multidisciplinary academic departments. It appeared that the more directly engaged in cutting-edge research in settings of deep-rooted conflict the peace studies field had become, the more sceptical various sectors of the academy – and often donors and legislatures – became of our work.

But in this challenging environment, the dynamic feedback between research and action emerged more clearly for a large portion of our field. That experience creates the meeting ground of peace and conflict studies education and sits at the heart of how this Special Edition emerged and frames our purpose. We seek to explore through very diverse disciplinary and thematic lenses the dynamic interdependencies of peace practice and scholarship. Such interdependencies provide the foundation for conflict engagement and challenge our understanding and approach, building a responsive and responsible approach to education.

How we arrived at this set of articles requires some background, context and the story of several classrooms and cohort of doctoral students at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies where we have been privileged to teach. The doctoral programme embeds a practice-focused course as a core curricular objective within the introductory requirements for the degree. Before describing the Kroc doctoral process, a review of trends and challenges in peace studies degree programmes is merited, particularly as these relate to doctoral-level engagement and the nexus between scholarship and practice.

On the side of academic programmes, while numerous degree programmes have emerged that focus specifically on peace or conflict studies and as such rely on multidisciplinary approaches, the wider peace studies field remains dominated by discipline-based specialists. As a result, the university incentives and focus place special emphasis on knowledge as produced by scholarship housed within particular methodological approaches and fields of specialization in peace studies. This poses a recurring challenge for highly complex and interdependent studies.

As practitioners on the other hand, whether fully recognized or not, we have tended to specialize into areas of engagement with the challenges of social change, conflict and peacebuilding. Sometimes practitioners debate whether and how our specific practices constitute a ‘field’ whether in mediation, human rights, humanitarian aid and development, or trauma-healing to name a few. These applied, grounded and real-time activities have led to a plethora of training and capacity-building workshops, conferences and policy-focused efforts that rarely converse well across their areas of specialization. Inevitably in the process, these same dynamic and evolving practices are named. They achieve a standing where a particular approach is referred to as a ‘model leading to this application’ coming under deeper scrutiny. Theories of change are interrogated and empirical evidence is sought, often initially based on evaluation or ‘lessons learned’ endeavours within the world of applied policy and practice. These ‘models’, in turn, soon become the focus of empirical studies, journal articles and theses.

More generally, academic degree programmes in peace studies now abound. Since the early first programmes of peace and conflict studies, where only a few could be found globally in the 1960s, hundreds of programmes now exist offering applied and research degrees, from campus-based programmes, to certificates and on-line courses. Any degree programme on peace and conflict studies writ large, no matter its professed orientation, will find that it navigates between demands – and at times tensions – of applied practice and scholarship. Within degree programmes, faculty and students experience this tug and pull between scholarship and practice around key questions: What constitutes valid knowledge? How did this knowledge emerge? How do real-life dilemmas and response inform our understanding and knowledge? And more often than we wish to admit: what knowledge matters and will be formally valued in the metrics of tenure within the wider academic community?

This Special Edition reflects the effort to explore the interdependencies and challenges of the common, though not always explicit, divides and tensions that exists in the pursuit of knowledge and practice within peace studies. This could emerge as a more rhetorical and somewhat abstract inquiry. In our case as professors at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, the pursuit of knowledge about the practice–scholar relationship lands each year in a required course required of all our doctoral students. Over the past four years, co-author Lederach taught this course under the official title of Strategic Peacebuilding: A Practice-Relevant Doctoral Seminar. The course compliments an introductory requirement that focuses more directly on theory and methodology of peace studies taught by co-author Lopez. Together we have worked with the cohort of doctoral students who author this volume of articles.

Teaching a practice-relevant doctoral seminar has always posed challenges. A fuller description of the context in which this course emerges for our doctoral students holds particular significance for the Special Edition. Early on, the Kroc Institute opted for a discipline-based degree with a trans-disciplinary focus on peace studies. In practice, this means that students apply to and are admitted into one of six existing mainstream academic departments at the University of Notre Dame. These currently include anthropology, history, political science, psychology, sociology and theology. Upon graduation, each student receives a doctoral degree in their particular department and they must follow all the core requirements for methodology, theory and knowledge required of that discipline. In addition, they also apply to and gain entrance to the doctoral programme in peace studies. In this, they follow a track of knowledge development around peace studies with requirements equal to those of their department in which they master the methods and theories of the wider peace studies field. They must pass through two comprehensive examinations related to the two fields. Their dissertation must receive final approval with committees that include professors from their home discipline and those related to peace studies. In essence, the students traverse two degrees with an orientation that builds towards integration.

The early gateway courses in peace studies track of their doctoral career are most commonly taken as a cohort. As the professors teaching those classes, we find ourselves seated with six to eight doctoral candidates each located in a different discipline who interact with the literature, methods, and knowledge base of conflict and peace studies writ large. In a rarely dull moment, we find that we are constantly navigating between discipline-specific discourse, method, theory and frameworks while addressing highly complex issues and challenges emerging around the growing understandings of peace and social change. Take as example the students framing in a jointly written paper that concluded their introductory course with Lopez.We find ourselves at the intersection of our single and multi-disciplinary pasts and our common interdisciplinary future. We know that completing a dual PhD in anthropology, political science, psychology, sociology or theology and peace studies will make us stronger peacebuilders … we have put our respective disciplines in conversation with one another to explore their strengths, weaknesses and niches within strategic peacebuilding. In doing so, we hope to honor the contributions already by these fields, highlight their latent research potential, and identify opportunities for interdisciplinary peacebuilding. (“Strategic Peacebuilding”, 2013)

And then we come to the challenge of a ‘practice-relevant’ full cohort seminar typically delivered in the second year of the degree programme. In the first few years, this course interacted directly with local NGOs engaged in peacebuilding. The NGO leadership posed research questions and dilemmas they faced on the ground that created the inquiry and discussion points for the class. For example, one cohort focused on the challenge of terrorism in East Africa and the discourse, theories and difficulties of international terrorism lists in highly conflicted specified geographies, in this case Somalia, and local relationships and peacebuilding initiatives affected by the sweeping terrorist listings. In this instance, each student developed a research inquiry around one or more of the questions submitted by the NGO, questions chosen around their particular discipline and the methodological capacity that permitted them to engage and contribute to the dilemmas experienced by the NGO.

This current Special Edition holds a series of articles that came from the cohort process in 2015 taught by John Paul Lederach. The orientation of the seminar held two objectives. First, it was ‘taught’ from the standpoint of a ‘practitioner-scholar’ where students have an opportunity to interact with both the perspectives of practice and the methodological challenges of an inductive approach to scholarship. Second, the seminar opened up the challenge of each student looking more carefully at how knowledge and key ideas have emerged, from early inception to the more rigorous testing. In this latter process, we interrogated how the academic world values knowledge and what counts as contributive to the wider development of empirical understanding and theory. Within peace studies, we explored the hypothesis suggesting that much of our knowledge base has had significant contribution from people who were exclusively or primarily practitioners, but this is rarely fully recognized by the academic parameters. This exploration necessarily opens up the challenge of complex and varied interdependencies that exist between what may be poorly captured by the terms ‘practitioner’ and ‘scholar’. At the start of the semester, we posed this dilemma: What if we tried to trace ‘formative practitioners’ and the rise of key theories, concepts or frameworks now widely accepted in the field to understand better the contribution of practice and practitioners to scholarship and knowledge in the field?

As any good doctoral seminar in peace studies should do, we negotiated our way into meaningful discussion, reading and research. We sought to understand how ways of knowing and being have contributed to the emergence, study and practice of ideas and approaches, especially those that become significant within the wider literature and field of peace studies writ large. Combining both the epistemological and ontological curiosity, we wanted to know how ideas and approaches emerge and contribute to the ‘study’ and ‘practice’ of peace and conflict engagement by looking at the evolution of concepts or the trajectory and impact of formative leaders. As a result this Special Edition provides a series of articles that began as research articles that emerged from this mix: discipline-based and trans-disciplinary interactive research focused on key figures and/or key concepts within peace studies and conflict engagement writ large with an effort to understand how knowledge and practice emerge, interact, achieve validation and at times find themselves in tension.

In the early part of the course, the touchstone for all the articles emerged around a practitioner–scholar spectrum developed as an orienting heuristic. As a brief description, the challenge of the binary of practitioner and scholar requires a more variable set of descriptions and a shift into a spectrum to identify a series of comparative ‘locations’ where interaction takes place. Placed initially as ideal types, this lens permitted our seminar to situate ways of engaging both the development and use of knowledge as well as looking more carefully at how individual practitioners and scholars have located themselves vocationally, an inquiry that some of the various articles developed with original research and interviews.

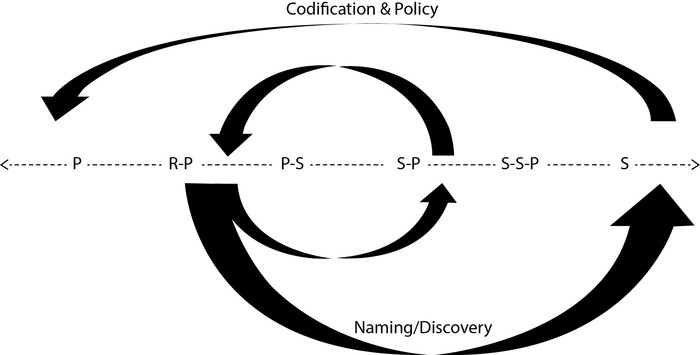

Figure 1 captures the visual spectrum and the short, early ideal-type descriptions of each location.

This heuristic device, which in many regards gives a different visualization to Bing’s assertion 25 years earlier, provided the gist for considerable discussion and constructive critique. While based on potential ideal types, we soon found that few people, practices or conceptual constructs remain fixed and static in a single location on the spectrum. Rather, we found consistently that ideas and people move, that is, they have fluid mobility that interacts across the continuum. This seemed particularly true of the middle-range ideal types, perhaps because the two extreme ends have much a narrower view of who they are and what is relevant to their vocational approaches. This ‘mobility’ and ‘interactivity’ may also account for how knowledge development requires an intimate connection between research and practice.

Within our seminar and then well beyond during the following year, each person developed an inquiry into either a concept (e.g. UN resolution 1325, ethics or security sector reform) or a set of engaged practitioners/scholars who have contributed to a particular arena with the purpose of exploring how the practice–scholar nexus has functioned and contributed in both directions on this spectrum. We were interested in understanding how knowledge was constructed and validated, and what this might suggest, in particular, for academic-related appointments and programmes. In the initial stages, our questions included: How has on-the-ground peacebuilding experience informed the rise of key categories of knowledge, methods, theories and ethical frameworks within peace studies? Or inversely, how has scholarship provided core conceptualizations and codification that have informed and shaped practice? How do the two interact from the view of distinct methodological and disciplinary lenses? How do particular area studies within theology, arts, indigenous struggle or the arena of ethics navigate the knowledge and practice spectrum?Figure 1 Practitioner–Scholar Spectrum Practitioner – engaged in demanding real-time, real context situations typically involving the application of practical responses (from policy to non-violent social action as examples) to real-world challenges facing social change with precious little time for reflection in the midst of demanding, highly dynamic and adaptive situations.

Practitioner – engaged in demanding real-time, real context situations typically involving the application of practical responses (from policy to non-violent social action as examples) to real-world challenges facing social change with precious little time for reflection in the midst of demanding, highly dynamic and adaptive situations.

Reflective-Practitioner – engaged practitioner who creates intentional space for reflection that takes the form of writing (in varied often briefings or monographs, and occasionally books) mostly directed towards improving understanding, lessons learned and applied approaches oriented towards their respective practitioner community.

Practitioner-Scholar – engaged practitioner with intentional reflection that also navigates into theory development and contribution to scholarship that attend both to practitioner needs and scholarship/research, for example in peer review journals or academic press books.

Scholar-Practitioner – engaged scholar who seeks to develop forms of direct practical application, though more commonly the practice emerges after the scholar has solidified his/her scholarly formation and academic position; in other words for many, this requires the achievement of tenure prior to engaging more directly in practice.

Scholar-Studies-Practitioner – engaged scholar who, as part of their scholarship, formally conducts research on and writes about practice in the field, but does not envision him/herself as an active practitioner.

Scholar – engaged scholar who does not envision practice as relevant to their research or that research concerns itself with practice.

In the latter stages in the development of the articles, we encouraged each author to engage their research topic and inquiry in ways that made sense to them and then to return to a single key question. What does my inquiry suggest about the approach to and how to organize the confluence of practice and scholarship? The authors’ engagement with and application of this query have led to the diverse and stimulating articles in this special issue.

Leo Guardado’s article illustrates liberation theology’s evolution and method, arguing that its manner of bridging the gap between theory and practice serves as a complement and challenge for conceptualizing this dynamic in peace studies. Through an analysis of Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez’ commitment to reflective pastoral practice among poor communities, Leo raises questions about what kinds of knowledge, and those of which investigators, are privileged in the academy. He argues for the possibility of continually sourcing wisdom from local communities, and about the necessity of scholars locating themselves within the realities and among the communities they study.

Dana Townsend and Kuldeep Niraula demonstrate how stories have the power to inspire social change and political transformation by adding narrative plurality, contextualization and local expertise to our collective understanding of peace and conflict. By creating a platform to transmit these stories, documentary filmmakers can bridge the gap between scholarship and practice by creating a process wherein each realm mutually informs the other. Filmmakers can use their medium to facilitate local healing and empowerment, while also creating a visual record of traditions and experiences that can be shared with a wider audience, and to inform current peacebuilding frameworks.

Using interviews and an inductive, interdisciplinary approach while also following the framework of The Moral Imagination (Lederach, 2005), Kathryn M. Lance aims to deconstruct the tension that emerges when framed as “scholarship or practice”? She accomplishes this by examining the tension from the perspective of a particular set of individuals – artists – who work along the practice–scholarship spectrum, but who are often overlooked in the wider literature. In providing the artists’ voice while paying special attention to how they make sense of their location(s) along the aforementioned spectrum, her article unearths fresh perspectives on the debate while furthering our understanding of the nexus between scholarship and practice.

Danielle Fulmer’s article demonstrates how international policy frameworks provide space for iterative engagement between peacebuilding scholars and practitioners by focusing on United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325, which prioritized gender mainstreaming in all stages of peacebuilding. Fulmer shows that the process of drafting and implementing UNSCR 1325 simultaneously legitimized practitioner projects to incorporate women in peacebuilding and narrowed their scope. This prompted critique and research from scholars and scholar-practitioners. The ensuing debates reveal how international policy frameworks can provide a space for iterative and productive discourse between scholars and practitioners by reaffirming shared normative objectives and making the contributions and limitations of both theory and practice visible.

In her article, Leslie MacColman examines security sector reform (SSR) as an organizing framework for one form of post-conflict peacebuilding and as a normative proposition with a set of real-time interventions that represents an exemplary case of the dialectic between scholarship and practice and an outstanding vantage point from which to interrogate this nexus. In particular, MacColman shows how the basic tenets of conflict transformation have led to critical reflection and a ‘new generation’ of critical scholarship on SSR, which in turn led to the ‘rediscovery’ of these concepts.

Jesse James provides an article on Native studies, a field in the United States in which many scholars count themselves as activists both in scholarship and practice because their central focus is service to the Native community. This field of study provides an interesting contrast to peace studies, a similarly interdisciplinary field that, while normatively committed to the study of peace, consists primarily of research that does not similarly commit the researcher in service to the practice of peace. James’ article utilizes first-person interviews and evaluates Native studies scholarship through the lens of activism as a model for practice-relevant scholarship in peace studies.

In her essay, Angela Lederach contends that heightened attention to and deliberative discussion of the ethical dilemmas inherent in peace studies offer a generative space of convergence for scholars and practitioners. She argues that peace studies is uniquely positioned to innovate ethical research practices capable of responding to the complex dynamics that emerge within settings of violence, precisely because of the interdependencies between research, action and education in the field of peace studies. She offers a framework for thinking about the complex, ethical landscape of peace research, outlining three guiding principles for ethical peace research practices: reflexivity, responsibility and reciprocity.

In the course of our discussions and the final development of the articles, we found significantly different ways of being with and developing knowledge as portrayed by a practitioner or scholarly imagination. In part, these were informed by varying methodologies and disciplines employed to develop the articles. However, in all cases, it led to a second iteration of the first graphic spectrum. In Figure 2, developed as a class, we envisioned two types of broad circular and interactive contributions captured by the graphic arrows.

Figure 2 Interactive Scholarship–Practice Spectrum In this iteration of the graph, we tried to understand better the highly interactive and interdependent processes between practice and scholarship emerging around the rise of concepts, frameworks and theories. The graph illustrates a circular inner dynamic often present between the ‘naming’ process taking place within daily practice and the ‘codification’ process that formalizes and often then has policy implications at a wider level. The research articles identified a number of insightful dynamics.

In this iteration of the graph, we tried to understand better the highly interactive and interdependent processes between practice and scholarship emerging around the rise of concepts, frameworks and theories. The graph illustrates a circular inner dynamic often present between the ‘naming’ process taking place within daily practice and the ‘codification’ process that formalizes and often then has policy implications at a wider level. The research articles identified a number of insightful dynamics.

On the one hand, practice through reflection about the dilemmas faced on-the-ground proposes experience-based formulations of dilemmas and discoveries that are named and become working concepts within the discourse of practitioners. These often emerged as dynamic practices in evolution in response to real-time challenges and problems faced within the purview of a particular engaged approach or activity. The naming may or may not have been theoretically intentional; rather, the language in use had become shorthand for a particular issue, approach or initiative. However, these named responses and ideas entered the public sphere, caught the attention of scholars and, in some instances, created pressure on a wider policy response. Invariably, they opened the opportunity for clarification of concept, dilemmas and theories of change. On the other hand, we found that scholarship, both in descriptive concept and empirical observation, intentionally created categories and codification of these practices that spoke to and made sense of the world but in the discourses useful to the world or academics and policy makers, the conclusions and even re-naming by scholars were not always embraced by practitioners leading at times to tensions.

One key consistently emergent in our inquiry exists between the practitioner dynamics of naming from experience and the formal scholarly codification as the latter may not fully respond to on-the-ground demands and at times mitigate the validity of the dynamic, evolving nature of practice. When their own ideas and actions are found in the world of academic knowledge and discourse, practitioners may experience a sense of second-class validity of their working understanding and do not find it easy to enter the discourse in scholarship. In other words, they can feel estranged from their own understanding. We found the framework useful for exploring these promises and tensions within the practitioner–scholar engagement.

The most significant insights we found can be stated in three simple conclusions. First, the shift towards fluid interaction with multiple ‘locations’ interacting across a spectrum of practice and scholarship was significant to get beyond the mostly inaccurate and limiting binary of ‘scholar–practitioner’. We found this to open up even wider potential we had not fully explored. For example, we found that teaching and pedagogy can often provide ways to engage both practice, through reflection, and scholarship; in other words, teaching as a mode of both further developing concept theory and teaching as a form of engaged action.

Second, building on this fluid interaction, we came to appreciate the highly dynamic interdependencies that exist between active practice and the dynamic development of knowledge. This suggests that much of the university’s protective cover that intentionally or not separates out the imaginations and insights of practitioners and scholars does not correspond to the actual rise of cutting-edge understanding and deepening knowledge and theory as it relates in particular to conflict engagement and peace studies. This would be equally true of the robust and rich interaction we found when highly different disciplines, theology to political science, interact constructively to explore the roots and soils from which ideas and knowledge emerge and return.

Finally, although somewhat outside the purview of this set of articles, our conversations opened time and again the challenge of the limited parameters and incentives within university structures. In particular, the narrowly defined departmental criteria of success and the wider tendency within university incentives that trend towards separating the world of legitimate research from practice mitigate against an understanding of knowledge as emerging within robust interdependency between the messy real-world engaged conflict transformation and empirically legitimate scholarship.

Reflecting on the iterative process of conversation, research and writing involved in these articles lead us back to an early observation of the students at the conclusion of their first introductory course with George Lopez. They stated:We argue that peace studies have, for too long, been comprised of isolated languages and theories of peace. The challenge for peace studies scholars today is how to be strategic. If peace studies is a map, each one of us must know how to situate our work within the wider landscape of research: As peace scholars, we must connect the parts in order to see the whole. Thus, with relinquishing the richness and specificity of our disciplinary homes, we must become comfortable ‘with’ and ‘in’ the texts and discourses of others. We believe that our research ‘thrives on unlikely alliances’ insomuch as it is able to innovate theories and understandings of a just peace called for by the current world context.

The articles in this Special Edition very much reflect a wider landscape in the spirit of parts aiming for a wider whole in the challenge of engaged conflict.

References Bing, A.G. (1989) Peace Studies as Experiential Education. In G.A. Lopez (Ed.), Peace studies: Past and future, the annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences (504) (pp. 48-60).

Lederach, J.P. (2005) The moral imagination: The art and soul of building peace. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Strategic Peacebuilding: An Organizing Framework for Peace Studies. First year conversations on interdisciplinary collaboration (unpublished – December 2013).

DOI: 10.5553/IJCER/221199652016004001001

International Journal of Conflict Engagement and Resolution |

|

| Editorial | The Dynamic Interdependencies of Practice and Scholarship |

| Keywords | peace research, scholar-practitioner, peacebuilding, peace education |

| Authors | John Paul Lederach en George A. Lopez |

| DOI | 10.5553/IJCER/221199652016004001001 |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

Suggested citation

John Paul Lederach and George A. Lopez, "The Dynamic Interdependencies of Practice and Scholarship", International Journal of Conflict Engagement and Resolution, 1, (2016):3-12

John Paul Lederach and George A. Lopez, "The Dynamic Interdependencies of Practice and Scholarship", International Journal of Conflict Engagement and Resolution, 1, (2016):3-12