-

A Introduction

With the construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, which began in 2015 and extends over more than 1,200 kilometres, connecting Ust-Luga, in Russia, to Greifswald, in Germany, the expectation was created that through the path of the infrastructure, via the Baltic Sea, 55 billion cubic metres of fuel has been transported per year to Europe1x Europétrole. Nord Stream 2. Rueil-Malmaison: Europétrole, 2020. Available at https://www.euro-petrole.com/a-volume-of-58-5-billion-cubic-metres-of-natural-gas-was-transported-through-the- nord-stream-pipeline-in-2019-n-i-20146. Last accessed 30 May 2023. – which would correspond to approximately 15% of the volume of gas exported to the European Union,2x União Europeia. European Parliament. The Nord Stream 2 Pipeline. Bruxelas: European Parliamentary Research Service, 2021a. Available at www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/690705/EPRS_BRI(2021)690705_EN.pdf. Last accessed 22 October 2021, p. 2. and almost 11% of all gas consumed in the block.3x União Europeia. European Commission. Quarterly Report on European Gas Market. Bruxelas: Market Observatory for energy, 2019a. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/quarterly_report_on_european_gas_markets_q4_2019_final.pdf. Last accessed 23 October 2021, p. 3.

Such a volume imported by the EU may be crucial to meet energy demand, given that the forecast is that demand for gas, by 2025, will remain stable in the bloc, while production of the resource will fall by around 40% in the territory,4x União Europeia. European Parliament. Gazprom’s Controversial Nord Stream 2 Pipeline. Bruxelas: European Parliamentary Research Service, 2017a. Available at www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2017/608629/EPRS_ATA(2017)608629_EN.pdf. Last accessed 22 October 2021, p. 3. increasing the importance of the Teuro-Russian gas pipeline.

However, judicial, geopolitical and environmental disputes have led to the suspension of construction on several occasions, notably due to the role of Gazprom, the Russian public company and controller of the gas pipeline – the fear is that such Russian control will undermine the bloc’s energy autonomy, shifting to Moscow the dominance of the European energy market.5x União Europeia (2021a, p. 1).

The main legal problems are summarized as follows: (i) it is a considerable investment in fossil fuels, reaching 9.5 billion euros, bringing relevant environmental concerns,6x Nord Stream 2 AG, (2018, p. 1). especially having considered that the EU has established targets for climate neutrality and decarbonization of the energy sector by 2050;7x União Europeia. European Commission. O que é o Pacto Ecológico Europeu. Bruxelas: European Commission, 2019b. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/pt/fs_19_6714. Last accessed 23 October 2021. (ii) fear that European geopolitics will be harmed, with the transfer of the energy domain to Russia; (iii) competitive and commercial concerns, namely in relation to the viability of the open gas market in the Union, against the control of Gazprom,8x União Europeia. European Commission. Antitrust: Commission Invites Comments on Gazprom Commitments Concerning Central and Eastern European Gas Markets. Bruxelas: European Commission, 2017b. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_17_555. Last accessed 23 October 2021. to be reinforced with Nord Stream 2.

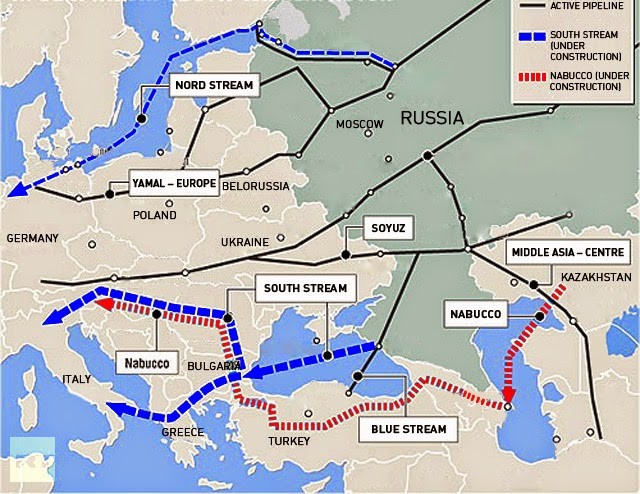

Such aforementioned problems intensify the role of the European Union in defining and implementing the legal and regulatory framework on the natural gas market, rescuing the episode of 2014, in which the European Commission prevented the South Stream gas pipeline, a gas pipeline that connected Russia to Bulgaria, was built under the justification that such a project did not respect the Third Energy Package.9x União Europeia (2017a, p. 2). In view of this, the main aspect involving the supranational link emerges: the effective implementation while respecting the EU regulatory and judicial decisions at the national level, even if they go beyond the original delegation attributed to it in the Constitutive Treaties.

Such questions have increased with the start of the military operation in Ukraine, led by Russia, since the beginning of 2022, reinforcing perceptions and fears about the European legal framework on the natural gas market and its dependence on Russian energy.

Therefore, the object of the research translates into the identification, based on a dogmatic and jurisprudential analysis, of the legal instruments used by the EU to regulate the natural gas market and have it applied at the national level. The general hypothesis to be answered is: is the principle of energy solidarity sufficient to explain supranational legislation and jurisprudence on the gas market?

In view of this, in the first section, the set of regulations that have the natural gas market as their object will be described, in particular, the changes made to enable the block to receive the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline. The next section will evaluate the judicial discussion about the conflict, which discussed about the German Courts and in the Court of Justice of the European Union. In the last section, the concept of energy solidarity and its implications in the face of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine will be investigated. -

B Origins and Development of European Regulation on the Natural Gas Market

Directives 90/377/EEC and 91/296/EEC, created in the early 1990s, inaugurated the regulation of the natural gas market in the European Union, being described as ‘the first phase of the completion of the internal natural gas market’ and aiming to increase competition in that market and price transparency for consumers of energy resources.10x União Europeia. European Parliament. Diretiva 2003/55/CE do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 26 de junho de 2003 que estabelece regras comuns para o mercado interno do gás natural. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L156/57. Bruxelas, 15 July 2003. Avalable at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32003L0055&from=EN. Last accessed 2 November 2021, p. 1.

The pair of aforementioned directives reflected six main lines: (i) competition and the interconnection and interoperability of the networks, leading to the acceleration of the completion of the internal natural gas market; (ii) progression and flexibility in such a market, in order to ‘take account of the diversity of market structures in the Member States’; (iii) some Member States depend on importing energy resources; (iv) it is up to some to impose ‘public service’ obligations, given that free competition would not guarantee consumer protection, environmental protection and security of supply; (v) it is necessary to define common, non-discriminatory criteria and procedures that do not restrict competition, in granting or authorizing the construction or operation of installations related to gas; (vi) the principle of subsidiarity would be respected by the EU, as it would merely establish common rules.11x União Europeia. European Parliament. Diretiva 98/30/CE do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 22 de junho de 1998 relativa a regras comuns para o mercado do gás natural. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L204/1. Bruxelas, 21 de julho de 1998. Availbale at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31998L0030&from=PT. Last accessed 2 November 2021, pp. 1-5.

With the finding of the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union that the two aforementioned directives did not ensure ‘fair competition’ and did not avoid the ‘risks of the occurrence of dominant positions in the market and predatory behaviour’,12x União Europeia (2003, pp. 1-2). Directive 2003/55/EC and Regulation 1775/2005 were created. Thus, the aim was to offer alternatives capable of assimilating ‘fundamental principles and rules regarding network access and third-party access services, congestion management, transparency, compensation and capacity rights transactions’.13x União Europeia. European Parliament. Regulamento no. 715/2009 do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 13 de julho de 2009 relativo às condições de acesso às redes de transporte de gás natural. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L211/36. Bruxelas, 14 August 2009b. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32009R0715&qid=1559727653524&from=PT. Last accessed 2 November 2021, p. 1. Thus, access to the network should be non-discriminatory, transparent and at fair prices.14x União Europeia (2003, p. 1).

To this end, the Directive, in its tenth recital, asserts that ‘it is convenient for the transmission and distribution networks to be operated by legally separate entities in cases where there are vertically integrated companies’ – with the exception, however, that the reality and competitive equity of the Member States could rule out such a claim. Furthermore, the rule determines that Member States must require companies to comply with ‘public service obligations’, so that they exploit gas following the principles of the Directive, protect consumers, ensure supply and enable competition, safety, environmental respect and non-discrimination between competitors.15x Ibid.

In 2007, the European Parliament once again focused its efforts on reflection and debate on EU energy security. In this context, the proposal of one of the parliamentarians was highlighted: the then vice-president of the house, Jacek Saryusz-Wolski, proposed the creation, in the long term, of a European ‘foreign policy’ in terms of energy – capable of satisfying ‘the Union’s interest and solidarity in crisis situations’.16x União Europeia. Parlamento Europeu. MEPs to Debate Renewable Energy and Foreign Energy Policy. Bruxelas: Europarl, 2007. Available at www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//NONSGML+IM-PRESS+20070921STO10534+0+DOC+PDF+V0//EN&language=RO. Last accessed 9 March 2022, p. 1. This was the second time that the term ‘energy solidarity’ was used in a meeting in Parliament, given that the previous year ‘solidarity’ had already been invoked in a discussion in the field of energy and the supply of energy to the Member States.17x União Europeia. Parlamento Europeu. Legislative Observatory. Bruxelas: Europarl, 2022c. Available at https://oeil.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/search/search.do?searchType=0. Last accessed 9 March 2022.

Two years later, the maturation of institutional reflection on the subject led the EU to conclude again that the then normative framework was not sufficient to achieve the aforementioned objectives. In light of this, Directive 2009/73/CE came into being, in which it was reinforced that the freedom of establishment and provision of services ensure ‘all consumers the free choice of suppliers and all suppliers the free supply of their customers’.18x União Europeia. European Parliament. Diretiva 2009/73/CE do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 13 de julho de 2009 que estabelece regras comuns para o mercado interno do gás natural. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L211/94. Bruxelas, 14 August 2009a. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/?qid=1429179228425&uri=CELEX:32009L0073. Last accessed 2 November 2021, p. 1; União Europeia (2009b).

Once again, as noted in recitals 6 and 8, the Directive reinforces that there must be a separation between the networks and the gas production and supply activities, so that Member States should prohibit a gas pipeline or network controller of transport was also a producer or trader, and vice versa. This rule, as provided for in recital 21, ‘should apply throughout the Community both for Community companies and for non-Community companies’ – the Commission, with the obligation to respect ‘solidarity and security in the energy sector in the Community’, reserves the possibility of allowing a single owner to operate both activities, if he is from a third country, ‘in order to avoid threats to public order and security in the Community and to the well-being of its citizens’. Note the express mention, for the first time, of ‘solidarity’, in the context of legislation on natural gas, in a Directive.19x União Europeia (2009a, pp. 4-6).

With the objective of allowing a ‘sufficient level of cross-border interconnection capacity and promoting the integration of markets’, Regulation no. 715/2009 is created based on the observation that there was discrimination in the conditions of access and supervision of the network20x União Europeia (2009b, p. 3). This normative diploma primarily regulates cross-border transport within the EU, although it also allows the granting of access services by third parties, ‘provided that they are subject to adequate guarantees by network users in relation to the solvency of such users’, according to Articles 14 and 15. It is also noted that the requirement of separation between the networks and the activities of production and supply of gas is maintained, so that the Member States must cooperate and supervise such activities, notably through sharing information about supply and demand, network capacity, flows, compensation and storage availability21x Recital 25 brings a caveat: if there is strategic commercial data, when there is a single user or when the data ‘relate to the exit points within a network or sub-network that are not connected to another transmission or distribution network, but to a single final industrial consumer’, there may be restrictions on sharing information União Europeia (2009b, p. 3).,22x União Europeia (2009b, p. 3). Despite these general guidelines, guidance could come from the Commission, the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER)23x Regulation 713/2009 creates ACER (Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators), with the attributions of coordinating the action of regulatory bodies on cross-border issues, in addition to overseeing wholesale markets and regulating cross-border energy infrastructure – subsequently ACER’s functions were reinforced in Regulation 2019/942 (União Europeia. European Parliament. Regulamento 2019/942 do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 5 de junho de 2019 que institui a Agência da União Europeia de Coordenação dos Reguladores de Energia. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L158/22. Bruxelas, 14 June 2019f. Availble at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019R0942&from=PT. Last accessed 2 November 2021, p. 1). and the ENTSO,24x ENTSO (European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas) should draw up a plan covering the ‘necessary regional interconnections’ and guaranteeing security of supply and commercial satisfaction. to ‘demand compliance with minimum requirements to achieve the necessary non-discriminatory and transparent access conditions’ in the gas market.25x União Europeia (2009b, p. 13).

It is in this context that the debate on the possible consequences of regulation in relation to the Nord Stream 2 project begins to gain importance: the legal consultants of the Commission26x Sokolov, Vitaly and Concha, Jaime. Brussels Admits EU Law Does Not Apply to Nord Stream 2. Energy Intelligence for Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, v.17, n. 186, set 2017. Available at www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Brussels-Admits-EU-Law-Does-Not-Apply-to-Nord-Stream-2.pdf. Last accessed 23 October 2021. and of the Council27x Gotev, Georgi. EU Council removes Nord Stream 2 legal hurdles. Euractiv, Bruxelas, 5 March 2018. Available at www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/industry-council-remove-nord-stream-2-hurdles/. Last accessed 23 October 2021. decided, in 2017, that the project could have the same controller for the production and transport activities, as such legislation would not apply to the referred gas pipeline. The finding is that EU law should not be applied, since one of the countries involved in the connection of the gas pipeline is not a Member State; therefore, the UN Convention for the Law of the Sea of 1982 should be applied.28x Sokolov and Concha (2017); Beckman, Karel. Who is afraid of Nord Stream 2?. Energy post, Amsterdam, 24 August 2016. Available at https://energypost.eu/afraid-nord-stream-2/. Last accessed 23 October 2021; Gragl, Paul. The Question of Applicability: EU Law or International Law in Nord Stream 2. Review of Central and East European Law, v. 44, 2019, pp. 1-31. Available at https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/58739/Gragl%20The%20Question%20of%20Applicability%3A%20EU%20Law%20or%20International%20Law%20in%20Nord%20Stream%202%202019%20Accepted.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y. Last accessed 12 November 2021. However, to prevent the Council, the Parliament and the European Commission from being able to coordinate the gas market in the Union, these actors decided to draw up a new Directive, which ensures that such restrictions are applied to the 22 kilometres of the gas pipeline that are in the waters under German jurisdiction.29x União Europeia. European Parliament. Diretiva 2019/692 do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 17 de abril de 2019 que altera a Diretiva 2009/73/CE que estabelece regras comuns para o mercado interno do gás natural. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L117/1. Bruxelas, 3 May 2019e. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019L0692&from=PT. Last accessed 2 November 2021, pp. 1-2.

With that, Directive 2019/692 came into force, which established that the same European standards would be applied to gas pipelines that connect ‘two or more Member States’, to gas pipelines ‘commencing and ending in third countries’ in the territory of the Member States and in their territorial sea. However, the Directive provides for an exception: if such gas pipelines starting and ending in third countries were completed before the rule came into force, it cannot be applied.30x União Europeia. European Parliament. Diretiva 2019/692 do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 17 de abril de 2019 que altera a Diretiva 2009/73/CE que estabelece regras comuns para o mercado interno do gás natural. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L117/1. Bruxelas, 3 May 2019e. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019L0692&from=PT. Last accessed 2 November 2021, pp. 1-2.

Since 2017, however, the European Commission has been concerned about the presence of the Russian state-owned company in the European gas market, so it demanded that Gazprom adopt some measures so that its operations in Central and Eastern Europe respected antitrust regulations: (i) remove contractual clauses that oblige the gas purchased to remain in a certain territory, in order to facilitate the free flow of gas in the region; (ii) ensure competitive prices, with adaptation to its costs; (iii) extinguish demands that are related to its dominance in the market, such as the South Stream project.31x União Europeia. European Commission. Antitrust: Commission Sends Statement of Objections to Gazprom for Alleged Abuse of Dominance on Central and Eastern European Gas Supply Markets. Bruxelas: European Commission, 2015. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_15_4828. Last accessed 2 November 2021; União Europeia (2017b).

In the same year, Regulation 2017/1938 was approved, which states that failures in the supply of gas can ‘affect all Member States, the Union and the Contracting Parties to the Treaty establishing the Energy Community’ – such an observation is consistent, once again, with the use of ‘solidarity’ as a justification for such normative action, according to the sixth recital, thus demanding a response at the supranational level against Russian dominance in the supply of gas, with greater cooperation and solidarity between the Member States.32x União Europeia. European Parliament. Regulamento 2017/1938 do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 25 de outubro de 2017 relativo a medidas destinadas a garantir a segurança do aprovisionamento de gás e que revoga o Regulamento (UE) no. 994/2010. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L280/1. Bruxelas, 28 de outubro de 2017c. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32017R1938&qid=1559727653524&from=PT. Last accessed 2 November 2021, pp. 1-3.

In this sense, the Commission would have the role of facilitating an agreement between the member countries of the EU, in order to guarantee a common assessment of the threats and the formation of emergency and prevention strategies against possible risks in the supply of gas. If Member States are unable to reach common terms, the Commission should suggest a cooperation mechanism suited to a risk group. Recital 10 of the Regulation indicates the elements of ‘energy solidarity’: solidarity is linked to regional cooperation, so that public authorities and gas companies must ‘mitigate the identified risks and optimize the benefits resulting from coordination measures and to apply the most cost-effective measures for consumers’.33x União Europeia (2017c).

Thus, considering the process of normative sedimentation on the subject and its current state of the art, it is possible to observe that the framework of EU law on the gas market continues to be based on six historical pillars: (i) active action by the Commission, the Agency and ENTSO in the regulation of gas, including its aspects of competition and energy security; (ii) sharing information about the gas market and its transportation; (iii) interconnection of existing networks and promotion of the construction of new gas pipelines and infrastructure; (iv) non-discrimination in service access, provision and pricing; (v) separation between supply and production activities; (vi) EU action restricted to the principle of subsidiarity and aligned with the principle of energy solidarity. -

C Judicialization of the Conflict Involving the Nord Stream 2 Gas Pipeline

With the transposition of the changes made in 2019 to ensure that Directive No. 2009/73 was applied to Nord Stream 2, the German energy regulatory agency ensured that such a project should follow the determinations set out in this new Directive. This formal decision is a response to the request of representatives of Nord Stream 2 who claimed to exceptionally apply the standard to the project – claim rejected on the grounds that the installations were not complete within the deadline established by 23 May 2019, the date in which such Directive came into force.34x Alemanha. Bundesnetzagentur. No Derogation from Regulation for Nord Stream 2. Berlin: Bundesnetzagentur, 2020a. Available at www.bundesnetzagentur.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2020/20200515_NordStream2.html;jsessionid=1A557721F83F4AD60B5F4BBA937005F5?nn=265794. Last accessed 23 October 2021.

In view of the regulatory agency’s refusal, Gazprom activated the German judicial protection: the Regional Court of Düsseldorf; however, on 25 August 2021, also rejected the company’s request, considering that Article 9 of Directive 2019/692 requires the separation between networks and gas production and supply activities. The Court found that the pipeline was not completed before 23 May 2019, and it was not enough that the investments in the project had already been finalized, dismissing Gazprom’s argument. Thus, it was evident that the date for ‘completion’ of the gas pipeline referred to the ‘physical’ completeness of the project and not the date of decision-making.35x Alemanha. Oberlandesgerichts Düsseldorf (Verfahren zuständige 3). VI-3 Kart 211/20. Düsseldorf: Oberlandesgerichts, 2021. Available at www.olg-duesseldorf.nrw.de/behoerde/presse/Presse_aktuell/20210825_PM_Nord-Stream-2/index.php. Last accessed 9 November 2021.

As an additional legal measure, the applicants sued the Court of Justice of the European Union, claiming the full annulment of the Directive in question, on the grounds that such rule did not respect the principles of non-discrimination, legal certainty and proportionality, in view of that by the indicated final date (23 May 2019), 95% of the gas pipeline was completed.36x União Europeia. Tribunal de Justiça da União Europeia. 8ª Secção. Processo T-526/19. ECLI:EU:T:2020:210. Autor: Nord Stream 2 AG. Réu: European Parliament e Council of the European Union. Luxemburgo, 20 de maio de 2020. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A62019TO0526%2801%29&qid=1636551204636. Last accessed 14 November 2021, pp. 2-4.

The Court weighed four central issues in its decision-making: (i) when transposing the Directive, the Member States were free to decide on the mode of separation adopted, an independent network or transport operator being required or even full separation between project structures; (ii) any of these options ‘would have considerable effects on the applicant’s situation’ and on the pipeline; (iii) the non-application of the Directive could only be effective if the gas pipeline was fully completed before the aforementioned date; (iv) the possibility for Gazprom to appeal to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) was conditional on compliance with two elements provided for in Article 263 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), namely that the Directive had effects ‘directly on the legal situation of the applicant’ and that ‘it does not leave any discretion to its addressees who are responsible for its implementation’. With that, the Court ruled out the possibility of admitting the annulment appeal of the norm, considering that it does not ‘directly concern the appellant’.37x União Europeia (2020, pp. 17-21).

However, such a premise excludes the possibility of challenging any Directive, since the Court stated that ‘a directive cannot, by itself, create obligations for an individual’ and that only acts that do not require measures of execution can be challenged.38x Ibid., p. 19. However, it is clear that any directive requires additional implementing measures39x The Advocate General of the CJEU states that directives can have three effects, even before transposition: ‘i) a blocking effect on national authorities that can have a negative effect on individuals […]; or ii) produce ancillary effects in the sphere of third parties […]; or iii) lead to an interpretation of national law in accordance with that directive that may be harmful to the individual […]’ (União Europeia. Conclusões do advogado-geral Bobek. ECLI:EU:C:2021:831. Processo C-348/20. Autor: Nord Stream 2 AG. Réu: European Parliament e Council of the European Union. Luxemburgo, 6 October 2021c. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/pt/TXT/?uri=CELEX:62020CC0348#Footnote13. Last accessed 10 November 2021, 2021c). – after all, Article 288, third paragraph of the TFEU, requires Member States to choose the means and manner in which they will pursue the objectives defined in such normative instrument.40x União Europeia. Tratado Sobre o Funcionamento da União Europeia. Jornal Oficial das Comunidades Europeias, C326/47. Luxemburgo, 26 de outubro de 2012. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT&from=PT. Last accessed 3 November 2021. Thus, any directive will require ‘additional implementing measures’, so that the CJEU’s strict position would mean closing the doors to the admissibility of appeals for the annulment of any directives.41x União Europeia (2021c).

Furthermore, the Advocacy General of the CJEU argues that the Court also made a mistake by equating ‘direct effect’ and ‘direct affect’.42x Ibid. It is worth mentioning that Article 263, fourth paragraph of the TFEU, requires that the contested act produce ‘legal effects in relation to third parties’, in order to be the object of an appeal to the Court;43x União Europeia (2012). however, it does not require that there be production of ‘direct effect’. Such controversy, therefore, for the admissibility of the appeal, must be assessed by the production of effects by the norm itself – and not by the subsequent additional measure, to be executed by the Member State or by the EU.

The CJUE’s decision seems to rule out the possibility of a directive directly affecting a subject’s legal status. However, it is possible for a directive to have a content and scope that implies a relevant legal change44x The Advocate General points out that ‘the direct affectation was declared in circumstances where the Union act in question exhaustively regulated the way in which the national authorities were obliged to take their decisions or the result to be achieved, regardless of the content of the specific mechanisms put in place. practice by national authorities to achieve this result; or when the role of the national authorities was extremely secondary and of a bureaucratic or purely mechanical nature; or when the Member States adopted simple ancillary measures in addition to the Union act in question’ (União Europeia, 2021c). – ‘the individual allocation aims to determine whether the appellant is affected due to specific circumstances that distinguish her from any other person who may also be affected’.45x União Europeia (2021c). In case T-233/01, the former Court of first instance decided that if an EU act, even if addressed to a Member State, has an action whose result is not ‘doubtful, then the act is of direct concern to any and all persons who are affected by that action’.46x União Europeia. Tribunal de Primeira Instância. 5ª Secção. Processo T-223/01. ECLI:EU:T:2002:205. Autor: Japan Tobacco Inc e JT International SA. Réu: Parlamento Europeu e Conselho da União Europeia. Luxemburgo, 10 September 2002. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:62001TO0223&from=PT. Last accessed 10 November 2021. In the case at hand, it is verified that Gazprom’s legal position was changed with this directive: its approval, even though it contains flexibility for Germany to define the model of separation of activities, implies an operational affectation and, potentially, company’s corporate structure – since there was no possibility that the gas pipeline would be completed and operational by 05/23/2019.47x União Europeia (2021c). That is, regardless of the model adopted, the legal situation of the parent company dora is already affected, a conclusion that the CJEU itself recognizes.48x União Europeia (2020, pp. 17-18).

From this, knowing that the appellant satisfies the first requirement, in the wake of the application of Article 263 of the TFEU, it is worth checking whether the second criterion is present: are there ‘implementation measures’ to be implemented by the Member States? In this specific case, it is clear that the main measure – derogation from the application of the 2019 Directive – is not possible, given that the gas pipeline would not be able to meet the time limit. In fact, as it did not meet the deadline of 23 May 2019, it is immediately known that the gas pipeline should have a different owner than its distributor or supplier. For the applicant, it is irrelevant that there is a margin of appreciation for the Member States to choose the model of separation of activities – the fact is that the separation will occur and will imply changes in the operation or in the corporate composition. This is clear from the statement that ‘the applicant will have to: (i) sell the entire Nord Stream 2 pipeline, (ii) sell the part of the pipeline under German jurisdiction or (iii) transfer ownership of the pipeline to a separate subsidiary’.49x União Europeia (2021c).

Although there is room for ‘implementation measures’ by the Member States, the applicant was effectively affected by a legislative decision of the European Union, given that the very existence of the directive, even if it needed to be transposed and implemented internally, implies damage to the operation and corporate structure of the company. Thus, it is observed that both requirements are provided for in Article 263 of the TFEU.

It is clear, therefore, that the appeal filed by Gazprom should have been admitted. But should it be valid? To answer the question, it is necessary to delve into the main concern of these pages: the principle of energy solidarity and its use in relations between Member States and the EU itself. To this end, another judgment from the same period will be used, which, in a similar way, deals with a Russian gas pipeline.

In Case T-883/16, Poland and the European Commission faced off in another judicial dispute. In 2016, the European Commission had approved a request by Gazprom to allow the use of more than half of the capacity of the OPAL gas pipeline, which is part of Nord Stream 1 – thus, the Russian state-owned company aimed to expand gas flows to more than 50% of OPAL’s capacity. Upon approval (and even though the Commission listed conditions to be met, such as the obligation that part of this capacity be sold through auctions), the objective was to prevent this expansion. Poland’s main concern was that such an increase in gas flow could endanger its energy security, given that this capacity expansion would allow ‘Gazprom to reduce the amounts of gas transiting Ukraine and Slovakia, as well as, in the long run, those transiting through Poland’. The Polish State thus requested the annulment of the Commission’s approval. To this end, the principle of energy solidarity among the Member States was invoked, in order to: (i) guarantee the proper functioning of the energy market; (ii) guarantee the Union’s energy security; (iii) promote energy efficiency and savings, in addition to fostering the development of new and renewable sources; (iv) promote the interconnection between the energy infrastructure.50x Munchmeyer, Max. Supercharging Energy Solidarity? The Advocate General’s Opinion in Case C-848/19 P Germany v. Poland. European Law Blog, pp. 1-10, April 2021. Available at https://europeanlawblog.eu/2021/04/09/supercharging-energy-solidarity-the-advocate-generals-opinion-in-case-c-848-19-p-germany-v-poland/#more-7597. Last accessed 5 March 2022; União Europeia. Tribunal de Justiça da União Europeia. 1ª Secção alargada. Processo T-883/16. ECLI:EU:T:2019:567. Autor: República da Polônia. Réu: Comissão Europeia. Luxemburgo, 10 September 2019g. Available at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1KQ47Q42-AsASnUi8_W_IkEZbDddVhVW8eeJFEhDSVpw/edit. Last accessed 10 March 2022.

For the first time, therefore, the CJUE was faced with the legal claim of the principle of energy solidarity. The European Court recognized that the European Commission did not observe this principle in its decision, since it represents a ‘general obligation’, and its application is not limited to exceptional situations of supply crisis or functioning of the internal gas market. Despite this, the Court also asserted that the principle does not prevent negative impacts from being experienced by any Member State in the energy field.51x Munchmeyer (2021); União Europeia (2019g). Reinforcing the material content of such a principle, the CJEU insists that the Union and the Member States must ‘avoid taking measures likely to affect the interests of the Union and the other Member States’, namely regarding energy security, economic viability and diversification of energy supply or its sources.52x União Europeia (2019g).

However, Germany appealed against this decision, arguing that: (i) the principle of energy solidarity is not a legal criterion, considering that it is abstract and incapable of imposing duties; (ii) this principle should only be invoked in emergency cases of gas supply shocks and under ‘strict assumptions’; (iii) the Commission took into account the potential effects of its decision on both Poland and the EU, therefore applying the principle, although not expressly demonstrated; (iv) the Commission’s decision only committed a formal error – not having expressed consideration of the principle of energy solidarity, which is why it should not be annulled.53x Munchmeyer (2021); União Europeia. Tribunal de Justiça da União Europeia. Recurso interposto em 20 November 2019 pela República Federal da Alemanha do Acórdão proferido pelo Tribunal Geral (Primeira Secção alargada) em 10 September 2019 no processo T-883/16, República da Polónia/Comissão Europeia. Recorrente: República da Alemanha. Outras partes: República da Polónia, Comissão Europeia, República da Letónia e República da Lituânia. Luxemburgo, 10 September 2019h. Available at https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=222692&pageIndex=0&doclang=PT&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=4962181. Last accessed 10 March 2022.

Opining on the case, EU Advocate General Manuel Campos Sánchez-Bordona understood that the principle of solidarity must be applied in EU decisions and is a principle that produces legal effects, even in situations where there is not necessarily a supply crisis. With this, the Advocate General seems to understand that the principle must be presumed in any and all spheres of European action, except when the Treaty refers to ‘political solidarity’.54x Munchmeyer (2021). In this way, the principle of solidarity should be respected both in its horizontal dimension (between Member States and third parties) and vertically (in the relationship between the EU and the States). However, it also points out that energy solidarity is not synonymous with energy security, although it is one of its components.55x União Europeia. Tribunal de Justiça da União Europeia. Conclusões do advogado-geral Manuel Campos Sánchez-Bordona. Processo C-848/19 P. Recorrente: República da Alemanha. Outras partes: República da Polónia, Comissão Europeia. Luxemburgo, 10 September 2019i. Available at https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=239008&pageIndex=0&doclang=PT&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=4962181. Last accessed 10 March 2022.

When judging the appeal, the CJEU ruled as follows: (i) the principle produces legal effects, capable of creating duties for the Member States and for the Union; (ii) the principle imposes a general obligation, to be respected also when there are no supply shocks or emergency situations; (iii) the Commission did not consider the impacts of the extension of the gas pipeline’s capacity on the Polish market, having only considered such effects on the Czech market; (iv) the Commission’s decision was annulled for violating the principle of energy solidarity and for a mere formal error.56x União Europeia. Tribunal de Justiça da União Europeia. Acórdão do Tribunal de Justiça (Grande Secção) de 15 de julho de 2021. Processo C-848/19 P. Recorrente: República da Alemanha. Outras partes: República da Polónia, Comissão Europeia. Luxemburgo, 10 September 2021e. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/pt/TXT/?uri=CELEX:62019CJ0848. Last accessed 10 March 2022.

Despite the fact that such judgment serves to give specific contours to the principle of solidarity, it is necessary to look into its theoretical and multidisciplinary dimensions. -

D The Consolidation of Energy Solidarity as a Principle of EU Law: Justifications and Challenges

The advent of modern problems raises not only regulatory issues and the effectiveness of the implementation of state policies, but also the constitution of social dynamics – currently, the intention is to release and, at the same time, limit the destructive effects of different ‘social energies’, namely with regard to the economy, science and technology, medicine and social media.57x Teubner, Gunther. Constitutional Fragments: Societal Constitutionalism and Globalization. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012; Medeiros, Rui. A constituição portuguesa num contexto global. Lisboa: Universidade Católica, 2015, p. 41. Since the previous movement, however, three phenomena have already been observed: (i) nation-states transfer governmental functions to transnational institutions and, partially, to non-state agents; (ii) ‘the extraterritorial effects of the actions of the nation-state create a law without democratic legitimacy’; (iii) ‘there is no democratic mandate for transnational governance’.58x Teubner (2012, p. 5).

The gas market is an example of the supranational dimension of law: the EU began to adopt for itself the coordination of gas market regulation and the institutional framework related to energy security.59x União Europeia. European Commission. European Energy Security Strategy: key priorities and actions. Bruxelas: Comissão Europeia, 2014. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/fr/SPEECH_14_505. Last accessed 23 October 2021; Chyong, Chi-Kong; Slavkova, Louisa; Tcherneva, Vassela. Europe’s Alternatives to Russian Gas. Berlim: European Council on Foreign Relations, 2015. Available at https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_europes_alternatives_to_russian_gas311666/. Last accessed 23 October 2021; Gragl (2019, p. 4). Article 194 of the TFEU makes this claim explicit and, at the same time, legitimizes European intervention in this field: with the justification of promoting and functioning of the internal market, in addition to preserving the environment, the Union would be responsible for drawing up policies in the field of energy, based ‘in a spirit of solidarity between the Member States’, although it assures them, the choice regarding ‘the conditions for exploiting their energy resources, their choice between different energy sources and the general structure of their energy supply’.60x União Europeia (2012).

It remains, therefore, to understand whether this constitutive legitimation was exercised within the limits imposed by the principle of subsidiarity. European institutional attributions must be limited to fulfilling the tasks listed in the TFEU, in order to avoid the unbridled expansion of competences at the supranational level, requiring answers to the following questions: would energy policies, without the implementation of Directive 2019/692, ensure the functioning of the energy market and the EU’s energy supply? Would they guarantee energy efficiency and the promotion of new and renewable energies?

The Copenhagen School serves as a theoretical guide to help understand that security-related issues should not be analysed exclusively from a political-military perspective. For such a School, the issue of security must also be addressed at other levels, such as the economic, social, energy sector, as long as their threats translate into relevant political effects.61x Buzan, Barry; Waever, Ole; de Wilde, Jaap. Security a New Framework for Analysis. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 1998, pp. 25); apud da Soler, Rafael. Interdependência energética securitizada: o caso da União Europeia e as suas consequências. Cadernos de Relações Internacionais, v. 1, n. 1, 2008. Available at www.maxwell.vrac.puc-rio.br/11721/11721.pdf. Last accessed 9 March 2022, p. 3. Using this theory as a basis,62x Da Soler (2008, p. 4). when addressing the theme of European energy, points out that the reference objects are the European economy and the citizens who consume imported energy resources, while the securitizing actor is the EU and the functional actor is the Russian state.

The author argues, however, that the Theory of Regional Security Complexes best explains the relationship between the European bloc and Russia: security complexes – regional groups on which security threats are more substantial – are the key point of this theory.63x Ibid., p. 5. Thus,64x Buzan, Barry and Waever, Ole. Regions and Powers. The Structure of International Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp. 343-344. find that Europe is formed by two main regional complexes: the EU and the post-Soviet space. Because of this, the objective of this approach is to identify the subjective perceptions that the securitizing actors have of the objective material aspects of the analysed domains. Given this, it is understood that such perceptions lead to the actions taken to neutralize the threat: ‘if the audience of this object accepts (submits without revolt) the existence of such a threat, the issue was in fact securitized’.65x Da Soler (2008, pp. 6-7).

Such a theory would be more appropriate, bearing in mind that, among European States, there are different levels of dependence on external energy resources: there are countries that depend little on energy from Russia – with percentages of dependence that reach 30% of imports, while there are other countries that depend entirely on Russian natural gas. The author’s observation is that the complex of the post-Soviet space, as it is very dependent on energy resources, facilitates the country’s claim to remain close to the former Soviet Republics and distance them from Western influence, namely the European Union. He also points out that, with the ‘Eastern expansion’ of the EU, cooperation made energy dependence asymmetric.66x Ibid., pp. 9-14.

Germany, in this context, would have a role in bringing the Russians closer to the West, considering that it is ‘the largest individual buyer of Russian energy and also the main source of foreign investment in this country’.67x Ibid., p. 15. Thus, its role is to serve as a bridge between matters of European and Russian interest.68x Rahr, Alexander. Germany and Russia: A Special Relationship. The Washington Quarterly, n. 30, 2007. pp. 137-145. Available at https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/olj/twq/spr2007/07spring_rahr.pdf. Last accessed 9 March 2022, p. 138.

However, some authors point to the role of the European Union in defining energy policy, having solidarity as a guiding principle: there is a need for the bloc to lead the process, in order to centralize actions and projects, giving less space for national policies, given that a threat can affect all Member States.69x Trentini, Bruno Rafael. As relações entre a União Europeia e a Rússia: dependência de gás natural, vulnerabilidades e o projeto da União Energética Europeia. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciência Política) – Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes,

Universidade Federal do Paraná. Curitiba, p. 152, 2018. Available at www.acervodigital.ufpr.br/bitstream/handle/1884/58287/R%20-%20D%20-%20BRUNO%20RAFAEL%20MACIEL%20TRENTINI.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Last accessed 09 March 2022, p. 135; Fernandes, Pedro Manuel Simões. Princípios da Governança Energética Global: a Segurança de Abastecimento na UE, China e EUA. Dissertação (Mestrado em Economia e Gestão) – Faculdade de Economia, Universidade do Porto. Porto, p. 99, 2019. Available at https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/bitstream/10216/124019/2/366048.pdf. Last accessed 9 March 2022, p. 13. Thus, such an observation goes against the bloc’s intentions, reflected in the Directives of 2019/692. Solidarity, in this context, has a decisive role, as recognized in the 2006 EU Green Paper. This publication lists six priority areas for improving energy security: (i) completing the domestic gas and electricity market; (ii) establishing solidarity mechanisms between Member States; (iii) building a more sustainable, efficient and diversified energy portfolio; (iv) having an integrated approach to tackling climate change; (v) defining a European strategic plan for energy technologies; (vi) establishing a coherent foreign policy in terms of energy.70x Martins, Inês de Melo Machado Azevedo. Indicadores para o estudo da segurança energética em Portugal. Dissertação (Mestrado em Engenharia do Ambiente) – Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. Lisboa, p. 169, 2013. Available at https://run.unl.pt/bitstream/10362/10433/1/Martins_2013.pdf. Last accessed 9 March 2022, p. 18.

As explained in the first section, the EU began its regulations on the gas market in the 1990s, based on general objectives, based, notably, on price transparency and greater competition in the market. As the first norms proved to be insufficient to ensure compliance with the objectives listed in Article 194, the EU has been expanding its attributions, with increasingly specific guidelines aimed at solving contemporary problems. Such ‘self-attribution’ was seen, for example, in the controversy over South Stream – another gas pipeline construction project, this time Bulgarian-Russian. This project was suspended after the European Commission decided that any infrastructure project, ‘promoted by dominant suppliers’, should adhere to the rules regarding the internal market and competition in the sector.71x União Europeia (2014).

The supranational power, in relation to the gas market, is also symbolized in the non-compliance action that the Commission filed against the Federal Republic of Germany, arguing that Article 2, point 20, Article 19, nos 3, 5 and 8 and Article 41, paragraphs 1 and 672x The text of para. 6 is: ‘Regulatory authorities are responsible for setting or approving, with sufficient time, before their entry into force, at least the methodologies to be used to calculate or establish the terms and conditions of: a) Connection and access to national networks, including tariffs for transmission and distribution and conditions and tariffs for access to LNG facilities […]; b) Provision of clearing services […]. Clearing services must be fair, non-discriminatory and based on objective criteria; and c) Access to cross-border infrastructure […]’ União Europeia (2009a). of Directive 2009/73/EC – which, eminently, prohibited the persons responsible for the management of ‘vertically integrated companies’, that is, those carrying out the activity of transport or distribution, in addition to production or marketing of natural gas, to combine activities or to be remunerated for combined activities – were not properly transposed. The conclusion of the CJUE was that Germany, as the Commission exposed it, did not carry out the transposition in the desired way.73x União Europeia. Tribunal de Justiça da União Europeia. 4ª Secção. Processo C-718/18. ECLI:EU:C:2021:662. Autor: Comissão Europeia. Réu: República Federal da Alemanha. Luxemburgo, 2 September 2021d. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:62018CJ0718&qid=1636549356787&from=EN. Last accessed 10 November 2021.

In this context, although it is admitted that the creation and expansion of the attributions of supranational organizations weaken the power of national States – including, this is the reason why the argument that international law is ‘only a product of ‘self-interest’ is refuted of the State’,74x Medeiros (2015, pp. 35-37). such expansion is justified if it satisfies the assumptions of the TFEU, namely its Article 194.

Similar to the explanation produced by the Theory of Regional Security Complexes, it is thought that the decisions of the European Union and its intention to address issues related to the gas market are justified from the geopolitical perspective: energy insecurity would deepen, if more gas projects were operationalized by an ‘unreliable partner’, such as Russia.75x Chyong et al. (2015). However, this perspective seems incomplete, after all, the European Commission has already used the same ‘antitrust’ arguments to justify an investigation into the Italian Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi (ENI): in 2007, the Commission investigated whether this company was abusing its dominant position in the gas market, by restricting the use of its natural gas transport network to competitors or by strategically reducing investments in network expansion.76x União Europeia. European Commission. Antitrust: Commission Welcomes ENI’s Structural Remedies Proposal to Increase Competition in the Italian Gas Market. Bruxelas: European Comission, 2010. Available at http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-10-29_en.htm?locale=en. Last accessed 7 November 2021.

This perception, when concatenated with the supranational normative framework explained in the previous sections, highlights the European initiative: coordinating regulation and promoting energy security in the EU, even if it prevents the full exercise of some powers traditionally understood as ‘national’. The principle of subsidiarity, based on this and the historical perspective previously presented, was met in this specific case.

However, in order to analyse the expansion of EU powers, it is necessary to face the argument used by those who defend the application of EU law to the case: the UN Convention for the Law of the Sea, in its Articles 60(2) and 80, admits that in the Exclusive Economic Zones, the national laws of the respective countries are applied77x Riley, Alan. Nord Stream 2: A Legal and Policy Analysis. CEPS Special Report, v. 151, nov. 2016, pp. 1-27. Available at http://aei.pitt.edu/81693/1/SR151AR_Nordstream2.pdf. Last accessed 12 November 2021, pp. 6-7; Gragl (2019). – as Nord Stream 2 passes: (i) through the territorial waters and the Russian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ); (ii) by the EEZ of Finland and Sweden; (iii) by the EEZ and by the Danish and German territorial sea, there are understandings that the gas pipeline would be subject to EU law, namely due to the fact that the Nordic countries and Germany are subject to it.

The Convention assigns to the national law of the country corresponding to the EEZ, the standardization of legal matters, among which are the installations and structures. On the other hand, Article 79 guarantees the installation of submarine cables and pipelines, even though there is an internal rule that prohibits it.78x Art. 79 of UNCLOS only allows for the limitation of the right to install submarine cables and pipelines, if the coastal State takes ‘reasonable measures’ to guarantee its exploitation of the continental shelf and its natural resources, as well as the prevention and control of pollution. Whether by application of Article 80, or by the application of Article 79, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) applies to the portion of the pipeline located in German territory. It is clear that the scope of application of EU law is broader when Article 80: UNCLOS ensures the application of national law – the application of European Directives and Regulations, in this context, as they influence national law, is indirectly ensured by Articles 60 and 80 of the Convention. However, European standards will be applied only if their scope of application is consistent with their founding Treaties. From this, in order to analyse whether EU law will apply in the specific case, two answers must converge: (i) Articles UNCLOS 79 or 80? (ii) Are the European norms adhering to the limitations and attributions that the Constitutive Treaties ensure?

It is undoubted that, in the EEZ and in the German territorial sea, Article 80 of UNCLOS culminates in the application of national law. However, national law itself is bound by the directives and regulations drawn up by the European institutions, after all, the Federal Republic of Germany is a Member State. Indirectly, therefore, it is undeniable that EU law, namely Directive 2019/692, will apply to the extension of the gas pipeline that is in the EEZ and in the German territorial sea.79x Gragl (2019); Riley (2016, pp. 3-5).

It remains, from this, to verify whether the aforementioned directive satisfies the powers attributed to the EU in its Constitutive Treaties. As explained earlier, the legitimacy of the Directive is based on the historical argument that previous directives were not sufficient to comply with the objectives set out in Article 194 of the TFEU. In fact, the essential difference between the 2019 Directive and the 2009 Directive is its scope of application: the 2019 directive defines that European standards, including those listed in the previous directive, will apply to gas pipelines beginning and ending in third countries. This justification, present in the recitals of Directive 2019/692,80x União Europeia (2019e). as a methodological duty, requires that, by imputing the ‘delegitimation’ of the EU in creating it, they also extend the argument of lack of legitimacy to previous European measures – after all, the 2019 Directive only expands the scope of application of the 2009 Directive. If the guidelines present in Directive 2019/692 are the same as those of the previous Directive, the matter should also be questioned in 2009. In this work, it will be assumed that the 2009 rule is linked to the limits imposed by Article 194 of the TFEU.

Evidently, as declined by the EU itself, (i) energy insecurity is still present; (ii) the energy market continues to require separation between network owners and distributors or suppliers; (iii) there is a need to promote renewable energies; (iv) the interconnection of energy networks is urgent.81x Ibid. That is, the EU demonstrates that it is acting within the limits delegated to it in Article 194 of the TFEU: as it is not possible to ensure the achievement of such objectives by the 2009 Directive alone, it is necessary to extend its scope of application to gas pipelines that start or end in territories of third countries. It should be noted that, at this moment, the argument of discrimination against Gazprom is not being contemplated – what is intended is to evaluate the argument of the EU’s lack of legitimacy when preparing Directive 2019/692.

It is therefore not possible to use the argument of the EU’s lack of legitimacy or casuistic action when preparing the 2019 Directive: from a historical perspective, the extension of its powers is justifiable and consistent, admitting similar extensions over time, under the argument of competition, price transparency and energy security – not only in the elaboration of norms, but also in antitrust investigations, such as the one that occurred against ENI, in 2007, it is notable that institutions are willing to cautiously and progressively expand their scope of action, to the extent that previous measures proved to be insufficient to fulfil the objectives set out in Article 194 of the TFEU.

The only reason, therefore, to depart from such a Directive would be discrimination against the Russian company: was the standard created to apply only to Nord Stream 2? As explained in the first section, since 2003, the EU attributes to the separation of control of transmission and distribution networks, an important factor to guarantee competition and reasonable prices. However, the construction of the pipeline only started in 2018. In 2003, not even the construction of Nord Stream 1 had started. The following table lists the cross-border gas pipelines, in EU territory, whose construction began in 2003.Table 1 Cross-border gas pipelines in EU territoryGas pipeline Construction start year Route Greenstream 2003 Libya-Italy Langeled 2004 Norway-UK South Wales 2005 Wales-England Interconnector TGI 2005 Turkey-Greece BBL 2006 Netherlands-UK Medgaz 2008 Algeria-Spain OPAL 2009 Germany-Czechia Nord Stream 2010 Russia-Germany Gazela 2010 Czechia-Germany South Stream 2012 Russia-Italy Trans-Anatolian 2015 Turkey-Greece & Bulgaria Trans Adriatic 2016 Greece-Italy Southern Gas Corridor 2018 Azerbaijan-Italy Nord Stream 2 2018 Russia-Germany Balticconnector 2018 Finland-Estonia Baltic Pipe 2020 Denmark-Poland Taking into account the deadline for completing the construction of the gas pipelines, it is noted that, based on the aforementioned table, from 2003 onwards, any European initiative would come up against the argument that such a normative proposal would be discriminatory in relation to the transmission networks that whether they start or end in third countries – after all, in 2003, 2005, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2015 and 2018, some construction started involving third countries.

The most notorious thing, however, is that the Russian state-owned company itself benefited from the European stagnation: if the 2019 Directive were in force, for example, in 2010, even Nord Stream 1 and the South Stream would be harmed – thus, in the same Just as it cannot be argued that the EU favoured Gazprom with its functional laziness, neither can it be argued that the 2019 rule was intended solely to harm Nord Stream 2.

It is undeniable that the establishment of an initial milestone, albeit late, is essential for the objectives listed in Article 194 of the TFEU are achieved and, due to the historical dimension of the construction of gas pipelines and European standardization, it is evident that the EU’s action, from the perspective of the Directive, is not discriminatory in relation to Nord Stream 2.

However, as widely exposed, it is also undoubted that there is a concern with energy dependence in relation, notably, to Russia. This perception was heightened after Russia’s military operation in Ukraine, which began in early 2022.

The European reaction to the military action reached the energy sector, after Germany announced the suspension of the certification of Nord Stream 2. Although the sanctions for Nord Stream 1 were not reached, the objective of Germany seems to be to limit the access of the Russian revenues obtained with the natural gas.82x Sourgens, Frédéric Gilles. Energy Lessons from the Ukraine Crisis. Ejil talk, pp. 1-3, February 2022. Available at www.ejiltalk.org/energy-lessons-from-the-ukraine-crisis/?utm_source=mailpoet&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=ejil-talk-newsletter-post-title_2. Last accessed 05 March 2022; Desierto, Diane. Non-Recognition. EJIL:Talk, pp. 1-17, February 2022. Available at www.ejiltalk.org/non-recognition/?utm_source=mailpoet&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=ejil-talk-newsletter-post-title_2. Last accessed 6 March 2022. That is, in addition to the judicial conflict discussed earlier, one more element began to involve this pipeline with the new invasion of Ukraine: the fear that Russia would use its energy powers as an instrument of domination and rescue of the influences of power in the former Soviet Republics.

In fact, the construction of the two gas pipelines is already seen as an attempt to reduce dependence on the Ukrainian infrastructure – the South Stream, for example, is a network of pipelines that transports Russian gas to Europe, but passes through several countries that charge a ‘transport tariff’, including Ukraine.83x Pereira, Fábio Manuel Farto Gonçalves. A dependência energética em termos de gás natural da União Europeia face à Rússia. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciência Polítia) – Faculdade de Letras, Universidade de Coimbra. Coimbra, p. 152, 2014. Available at https://estudogeral.uc.pt/bitstream/10316/27377/1/Disserta%C3%A7%C3%A3o.pdf. Last accessed 6 March 2022, pp. 50-53; Sourgens (2022). However, with the recent Russo-Ukrainian episode, European concern was not restricted to extra-German judicial and normative channels. The suspension of certification of Nord Stream 2 was carried out, although this harmed the economic interests of its nationals: gas prices reached record levels in Europe in mid-March, briefly surpassing 300 euros per megawatt-hour – for comparison purposes, in the previous year, the value did not exceed 30 euros per megawatt-hour.84x Wallace, Joe. Natural-Gas Prices in Europe Jump to Record Highs as War Intensifies. The Wall Street Journal, pp. 1-4, March 2022. Available at www.wsj.com/livecoverage/russia-ukraine-latest-news-2022-03-07/card/natural-gas-prices-in-europe-jump-to-record-highs-as-war-intensifies-RZeWDEgiOYW2XbAIJjTh. Last accessed 9 March 2022.

Faced with the decision taken after the military episode in Ukraine, it is possible to observe that Germany decided to adopt the principle of energy solidarity – even if not completely, after all, Russian gas is still flowing through the 1st Nord Stream, illustrating its meaning: even if their national position could be strengthened with a certain conduct – more controlled prices of the energy resource, solidarity requires that decisions be taken in such a way as to encompass the interests of all Member States, such as energy security and sovereignty of the countries of the East that are part of the block. Even though it is an ‘emergency situation’, the German decision demonstrates that the country has changed its perception related to the principle – the defence of the ‘abstraction’ of the principle of energy solidarity, argued in case T-883/16, appears to have been changed after such a conflict.

The German decision, however, boosted the joint action of the European Union, led by the Commission, called ‘Market Correction Mechanism’,85x União Europeia. Comissão Europeia. Commission Proposes a New EU Instrument to Limit Excessive Gas Price Spikes. Bruxelas: Comissão Europeia, 2022a. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_7065. Last accessed 31 December 2022. in order to establish a limit to the price of gas in the block: the maximum tradable value will be 180 euros per megawatt-hour and will come into effect on 15 February 2023. After approval by the Union Council, the mechanism will be activated automatically whenever, cumulatively: (i) the price of gas derivatives, traded on the European futures market – the Title Transfer Facility (TTF) – exceed such reference value for at least three business days; (ii) the difference between the TTF price and the global gas price (LNG) is greater than 35 euros per megawatt-hour, for at least three business days.86x União Europeia. Consellho da União Europeia Europeia. Council Agrees on Temporary Mechanism to Limit Excessive Gas Prices. Bruxelas: Conselho da União Europeia, 2022b. Available at www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/12/19/council-agrees-on-temporary-mechanism-to-limit-excessive-gas-prices/?utm_source=dsms-auto&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Council+agrees+on+temporary+mechanism+to+limit+excessive+gas+prices. Last accessed 31 December 2022. Thus, when both conditions are met, ACER will publish a notice, communicated to the European Central Bank, the European Commission and the European Securities and Markets Authority, so that any order in European futures market that exceeds such ceiling shall be automatically disregarded.87x União Europeia (2022a). -

E Conclusion

The purpose of this work was to investigate whether the principle of energy solidarity is sufficient to explain supranational legislation and jurisprudence on the European gas market. The specific objective was to investigate whether Directive 2019/692 is adequate to the institutional attribution that the TFEU confers on the EU in the field of gas, based on five aspects: (i) does the rule satisfy the principle of subsidiarity? (ii) should UNCLOS or EU law have been applied? (iii) Did the EU inaugurate a rule to apply over Nord Stream 2 or is it a historically considered rule? (iv) Is the extension of the EU’s attributions, to also cover gas pipelines that start or end in third countries, legally coherent or is it case by case? (v) Is the Directive discriminatory against Gazprom?

At first, the means was to go through the normative elements of EU law, with the particular intention of fixing Directive 2019/692 in a historical perspective. Under this pillar, it became evident that the EU began its standardization with generic objectives, in the 90s, starting to delimit more specific and targeted norms, as previous normative proposals proved to be insufficient to ensure price transparency, competition and energy security. Thus, the principle of subsidiarity would be complied with, in the same way that historically situated legal coherence and institutionality were also present in the concrete case, especially considering that the rule on the separation of control of the network and gas distribution is located in the European environment since 2003.

Similarly, by analysing the text of the UNCLOS and the TFEU itself, it became evident that, for what was of interest to the object of this research, EU law would apply to Nord Stream 2, albeit indirectly. Finally, it was shown that the Directive is not discriminatory, since, from 2003 onwards, in any period that the EU elaborates the rule in question, there would be a cross-border gas pipeline under construction, including networks owned by Gazprom itself.

More recently, the military crisis between Russia and Ukraine brought more legal innovations in relation to the principle of energy solidarity adopted by the EU and the Member States to regulate the European gas market: from provisions on Nord Stream 2 to the establishment of a ceiling of gas prices, it was perceived that the bloc’s energy security requires a concerted action between the interested actors, even if national interests are immediately sidelined due to European pretensions. -

1 Europétrole. Nord Stream 2. Rueil-Malmaison: Europétrole, 2020. Available at https://www.euro-petrole.com/a-volume-of-58-5-billion-cubic-metres-of-natural-gas-was-transported-through-the- nord-stream-pipeline-in-2019-n-i-20146. Last accessed 30 May 2023.

-

2 União Europeia. European Parliament. The Nord Stream 2 Pipeline. Bruxelas: European Parliamentary Research Service, 2021a. Available at www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/690705/EPRS_BRI(2021)690705_EN.pdf. Last accessed 22 October 2021, p. 2.

-

3 União Europeia. European Commission. Quarterly Report on European Gas Market. Bruxelas: Market Observatory for energy, 2019a. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/quarterly_report_on_european_gas_markets_q4_2019_final.pdf. Last accessed 23 October 2021, p. 3.

-

4 União Europeia. European Parliament. Gazprom’s Controversial Nord Stream 2 Pipeline. Bruxelas: European Parliamentary Research Service, 2017a. Available at www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2017/608629/EPRS_ATA(2017)608629_EN.pdf. Last accessed 22 October 2021, p. 3.

-

5 União Europeia (2021a, p. 1).

-

6 Nord Stream 2 AG, (2018, p. 1).

-

7 União Europeia. European Commission. O que é o Pacto Ecológico Europeu. Bruxelas: European Commission, 2019b. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/pt/fs_19_6714. Last accessed 23 October 2021.

-

8 União Europeia. European Commission. Antitrust: Commission Invites Comments on Gazprom Commitments Concerning Central and Eastern European Gas Markets. Bruxelas: European Commission, 2017b. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_17_555. Last accessed 23 October 2021.

-

9 União Europeia (2017a, p. 2).

-

10 União Europeia. European Parliament. Diretiva 2003/55/CE do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 26 de junho de 2003 que estabelece regras comuns para o mercado interno do gás natural. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L156/57. Bruxelas, 15 July 2003. Avalable at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32003L0055&from=EN. Last accessed 2 November 2021, p. 1.

-

11 União Europeia. European Parliament. Diretiva 98/30/CE do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 22 de junho de 1998 relativa a regras comuns para o mercado do gás natural. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L204/1. Bruxelas, 21 de julho de 1998. Availbale at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31998L0030&from=PT. Last accessed 2 November 2021, pp. 1-5.

-

12 União Europeia (2003, pp. 1-2).

-

13 União Europeia. European Parliament. Regulamento no. 715/2009 do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 13 de julho de 2009 relativo às condições de acesso às redes de transporte de gás natural. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L211/36. Bruxelas, 14 August 2009b. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32009R0715&qid=1559727653524&from=PT. Last accessed 2 November 2021, p. 1.

-

14 União Europeia (2003, p. 1).

-

15 Ibid.

-

16 União Europeia. Parlamento Europeu. MEPs to Debate Renewable Energy and Foreign Energy Policy. Bruxelas: Europarl, 2007. Available at www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//NONSGML+IM-PRESS+20070921STO10534+0+DOC+PDF+V0//EN&language=RO. Last accessed 9 March 2022, p. 1.

-

17 União Europeia. Parlamento Europeu. Legislative Observatory. Bruxelas: Europarl, 2022c. Available at https://oeil.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/search/search.do?searchType=0. Last accessed 9 March 2022.

-

18 União Europeia. European Parliament. Diretiva 2009/73/CE do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 13 de julho de 2009 que estabelece regras comuns para o mercado interno do gás natural. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L211/94. Bruxelas, 14 August 2009a. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/?qid=1429179228425&uri=CELEX:32009L0073. Last accessed 2 November 2021, p. 1; União Europeia (2009b).

-

19 União Europeia (2009a, pp. 4-6).

-

20 União Europeia (2009b, p. 3).

-

21 Recital 25 brings a caveat: if there is strategic commercial data, when there is a single user or when the data ‘relate to the exit points within a network or sub-network that are not connected to another transmission or distribution network, but to a single final industrial consumer’, there may be restrictions on sharing information União Europeia (2009b, p. 3).

-

22 União Europeia (2009b, p. 3).

-

23 Regulation 713/2009 creates ACER (Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators), with the attributions of coordinating the action of regulatory bodies on cross-border issues, in addition to overseeing wholesale markets and regulating cross-border energy infrastructure – subsequently ACER’s functions were reinforced in Regulation 2019/942 (União Europeia. European Parliament. Regulamento 2019/942 do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 5 de junho de 2019 que institui a Agência da União Europeia de Coordenação dos Reguladores de Energia. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L158/22. Bruxelas, 14 June 2019f. Availble at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019R0942&from=PT. Last accessed 2 November 2021, p. 1).

-

24 ENTSO (European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas) should draw up a plan covering the ‘necessary regional interconnections’ and guaranteeing security of supply and commercial satisfaction.

-

25 União Europeia (2009b, p. 13).

-

26 Sokolov, Vitaly and Concha, Jaime. Brussels Admits EU Law Does Not Apply to Nord Stream 2. Energy Intelligence for Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, v.17, n. 186, set 2017. Available at www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Brussels-Admits-EU-Law-Does-Not-Apply-to-Nord-Stream-2.pdf. Last accessed 23 October 2021.

-

27 Gotev, Georgi. EU Council removes Nord Stream 2 legal hurdles. Euractiv, Bruxelas, 5 March 2018. Available at www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/industry-council-remove-nord-stream-2-hurdles/. Last accessed 23 October 2021.

-

28 Sokolov and Concha (2017); Beckman, Karel. Who is afraid of Nord Stream 2?. Energy post, Amsterdam, 24 August 2016. Available at https://energypost.eu/afraid-nord-stream-2/. Last accessed 23 October 2021; Gragl, Paul. The Question of Applicability: EU Law or International Law in Nord Stream 2. Review of Central and East European Law, v. 44, 2019, pp. 1-31. Available at https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/58739/Gragl%20The%20Question%20of%20Applicability%3A%20EU%20Law%20or%20International%20Law%20in%20Nord%20Stream%202%202019%20Accepted.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y. Last accessed 12 November 2021.

-

29 União Europeia. European Parliament. Diretiva 2019/692 do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 17 de abril de 2019 que altera a Diretiva 2009/73/CE que estabelece regras comuns para o mercado interno do gás natural. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L117/1. Bruxelas, 3 May 2019e. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019L0692&from=PT. Last accessed 2 November 2021, pp. 1-2.

-

30 União Europeia. European Parliament. Diretiva 2019/692 do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 17 de abril de 2019 que altera a Diretiva 2009/73/CE que estabelece regras comuns para o mercado interno do gás natural. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L117/1. Bruxelas, 3 May 2019e. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019L0692&from=PT. Last accessed 2 November 2021, pp. 1-2.

-

31 União Europeia. European Commission. Antitrust: Commission Sends Statement of Objections to Gazprom for Alleged Abuse of Dominance on Central and Eastern European Gas Supply Markets. Bruxelas: European Commission, 2015. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_15_4828. Last accessed 2 November 2021; União Europeia (2017b).

-

32 União Europeia. European Parliament. Regulamento 2017/1938 do Parlamento Europeu e do Conselho de 25 de outubro de 2017 relativo a medidas destinadas a garantir a segurança do aprovisionamento de gás e que revoga o Regulamento (UE) no. 994/2010. Jornal Oficial da União Europeia, L280/1. Bruxelas, 28 de outubro de 2017c. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32017R1938&qid=1559727653524&from=PT. Last accessed 2 November 2021, pp. 1-3.

-

33 União Europeia (2017c).

-

34 Alemanha. Bundesnetzagentur. No Derogation from Regulation for Nord Stream 2. Berlin: Bundesnetzagentur, 2020a. Available at www.bundesnetzagentur.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2020/20200515_NordStream2.html;jsessionid=1A557721F83F4AD60B5F4BBA937005F5?nn=265794. Last accessed 23 October 2021.

-

35 Alemanha. Oberlandesgerichts Düsseldorf (Verfahren zuständige 3). VI-3 Kart 211/20. Düsseldorf: Oberlandesgerichts, 2021. Available at www.olg-duesseldorf.nrw.de/behoerde/presse/Presse_aktuell/20210825_PM_Nord-Stream-2/index.php. Last accessed 9 November 2021.

-

36 União Europeia. Tribunal de Justiça da União Europeia. 8ª Secção. Processo T-526/19. ECLI:EU:T:2020:210. Autor: Nord Stream 2 AG. Réu: European Parliament e Council of the European Union. Luxemburgo, 20 de maio de 2020. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A62019TO0526%2801%29&qid=1636551204636. Last accessed 14 November 2021, pp. 2-4.

-

37 União Europeia (2020, pp. 17-21).

-

38 Ibid., p. 19.

-

39 The Advocate General of the CJEU states that directives can have three effects, even before transposition: ‘i) a blocking effect on national authorities that can have a negative effect on individuals […]; or ii) produce ancillary effects in the sphere of third parties […]; or iii) lead to an interpretation of national law in accordance with that directive that may be harmful to the individual […]’ (União Europeia. Conclusões do advogado-geral Bobek. ECLI:EU:C:2021:831. Processo C-348/20. Autor: Nord Stream 2 AG. Réu: European Parliament e Council of the European Union. Luxemburgo, 6 October 2021c. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/pt/TXT/?uri=CELEX:62020CC0348#Footnote13. Last accessed 10 November 2021, 2021c).

-

40 União Europeia. Tratado Sobre o Funcionamento da União Europeia. Jornal Oficial das Comunidades Europeias, C326/47. Luxemburgo, 26 de outubro de 2012. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PT/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT&from=PT. Last accessed 3 November 2021.

-

41 União Europeia (2021c).

-

42 Ibid.

-

43 União Europeia (2012).

-