-

A Introduction

Within the European Union (EU), border regions represent 40% of its territory, and they are home to a third of the EU’s population.1x European Commission (2017). ‘Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament: Boosting growth and cohesion in EU border regions’, COM(2017) 534 final. Located at the edge of national borders (i.e. the EU’s internal borders), these regions provide opportunities to reap benefits from interactions of different cultures, languages, markets and societies.2x See for example Lambertz, K. (2010). Die Grenzregionen als Labor und Motor kontinentaler Entwicklungen in Europa. Schriften zur Grenzüberschreitenden Zusammenarbeit, Band 4. However, from a law-making point of view, these regions – and particularly from a cross-border perspective – pose specific challenges. (Cross-)border regions, in fact, provide prime stages for conflicts of laws. Given the general absence of physical borders within the EU, (cross-)border regions are the places where the ‘products’ (i.e. the laws and regulations) of two or more national legal systems meet and interact on a daily basis.3x See for example Beck, J. (2018). Cross-Border Cooperation: Challenges and Perspectives for the Horizontal Dimension of European Integration. Administrative Consulting, (1):56-62. Ulrich, P. (2021). Participatory Governance in the Europe of the Cross-border Regions. Cooperation – Boundaries – Civil Society. Baden-Baden: Nomos. The European Commission refers to border regions as ‘Living labs of European Integration’ [emphasis added], where both the effects of free movement and remaining obstacles to integration are most visible.4x European Commission (2021a). ‘Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: EU Border Regions: Living labs of European integration’, COM(2021) 393 final. For instance, the crisis management of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a clear example of how border regions can be hindered and hampered by uncoordinated policies and regulations, especially as regards the vivid application of the free movement principle.5x Unfried, M. (2020). Cross-border governance in times of crisis: first experiences from the Euroregion Meuse-Rhine. The Journal of Cross-Border Studies in Ireland, No. 15. pp. 87-96. Schneider, H., Kortese, L., Mertens, P., & Sivonen, S. (2021). Cross-border mobility in times of COVID-19: Assessing COVID-19 Measures and their Effects on Cross-border Regions within the EU. EU-CITZEN, available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/eu-citzen_-_report_on_cross-border_mobility_in_times_of_covid-19.pdf.

The aforementioned (legislative and administrative) interactions between national systems both originate from and generally hamper or, at least, complicate the cross-border mobility of workers, businesses and citizens, as well as the cross-border cooperation between local, regional and national authorities. Therefore, we will refer to them as ‘border effects’. In a Union founded on the idea of ‘Unity in diversity’, these obstacles are part of daily life in (cross-)border regions.

From the outset, it is useful to clarify first the different concepts ‘regions’, ‘border regions’ and ‘cross-border regions’.6x This distinction is referring to the categories as described in Klatt, M. (2021). Diesseits und jenseits der Grenze - das Konzept der Grenzregion. In D. Gerst, M. Klessmann, & H. Krämer (Eds.), Grenzforschung: Handbuch für Wissenschaft und Studium(pp. 143-155). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft. Border Studies, Cultures, Spaces, Orders Vol. 3 https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845295305. The geographical shape and the administrative or legislative competences of regions are defined by the national constitutions of the Member States. This means that this ranges from regions with extensive legislative competences, strong parliaments and financial sovereignty (as in the case of Belgium) to regions with little or no competences therein. In some Member States, regions do not exist at all as a political or administrative category but exist instead as a geographical or statistical category.7x In this sense, the EU category NUTS 3 region, for instance, is the common statistical category. See https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts/nuts-maps. Importantly, with the Maastricht Treaty, regions – as a political entity – gained a defined advisory role during the legislative process at the EU level. They have the right to articulate recommendations with respect to proposals of the European Commission and officially address them to the two legislator institutions, the Council and the European Parliament. They fulfil this role within the framework of the Committee of the Regions (CoR), established in 1993.8x The legal basis of the Committee of the Regions is today Art. 13(4) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), Arts. 300 and 305 to 307 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). By now, the role of regions in policymaking, and especially in the implementation of legislation, has become indispensable. Each Member State is characterized by a unique form of political organization and division of competencies. To understand the actual effects of both national and European legislation on the life of citizens and businesses, a regional focus is most insightful and instructive.

The notion of border regions refers in the first place to this national concept of ‘region’, meaning regions defined by national constitutions that are geographically located at an internal or external border of the EU. Adding the cross-border perspective, today, we see a variety of different Euroregions, Eurodistricts or other cross-border territories that exist with differing degrees of institutionalization. Several research projects have tried to describe a typology of cross-border territory or entities such as the ones mentioned.9x The latest and very comprehensive project results were published in 2018 by the University of Barcelona, see: Durà, A., F. Camonita, M. Berzi, & A. Noferini (2018). Euroregions, Excellence and Innovation across EU borders. A Catalogue of Good Practices. Barcelona: Department of Geography, UAB. In this article, the working definition of a ‘cross-border region’ focuses on the notion of the Euroregions.10x See http://www.espaces-transfrontaliers.org/en/resources/territories/euroregions/. Many are established across Europe as some form of shared administrative structure, which links (local and regional) administrations across one or more national borders, representing the border regions that cooperate most closely across borders. More elaborate and established Euroregions also formulate strategies and objectives for the development of the cross-border territory, these can be seen as valuable benchmarks when measuring positive or negative effects of different policies.

The territorial dimension in the European legal framework was strengthened with the Lisbon Treaty, amending Article 174 TFEU.11x Formerly, Art. 158 Treaty establishing the European Community (TEC). It adds the emphasis on territorial cohesion, next to social and economic cohesion, and stipulates that special attention should be paid (inter alia) to cross-border regions.12x Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community (2007/C 306/01). The Lisbon Treaty added the emphasis on territorial cohesion, next to social and economic cohesion. Indeed, the Commission has recently recognized in its 2021 report on Better Regulation the need to improve the Impact Assessment of EU policies by taking into account the perspective of, among others, cross-border areas.13x European Commission (2021b). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and Council, Joining forces to make better laws, available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/files/better-regulation-joining-forces-make-better-laws_en, p. 15. Removing and limiting the introduction of cross-border obstacles are thus already on the EU’s agenda;14x See in this regard also Council of Europe (2012). Manual on removing obstacles to cross-border cooperation. Strasbourg, November 2012. however, the means to effect better regulation for border regions still seem to be lacking. Hence, this article departs from the premise that for the advancement of EU integration – and with it Better Regulation – such border effects require recognition in European law-making and application in the evidence-based legislative process. The central question is how a cross-border impact assessment during the legislative process can ensure better regulation in the light of regional policy.

To answer this question, the article follows the structure explained here. The first section reflects on the nature and origins of cross-border obstacles. It will provide concrete case examples of EU policies where the so-called ‘cross-border effects’ can be analysed. The second section will discuss the practice of a bottom-up regulatory cross-border impact assessment as a method for identifying and assessing possible effects for cross-border regions in the context of evidence-based law-making. The third section will elaborate further on what the current state of affairs in EU’s policymaking and impact assessment looks like. In this context, we will discuss how a cross-border impact assessment would fit within the procedure of EU’s policymaking and other initiatives. Finally, the contribution will summarize the main findings and discuss some policy recommendations. -

B Cross-Border Obstacles

In its Communication from 2017 ‘Boosting growth and cohesion in EU border regions’, the European Commission proposed different instruments to overcome barriers to cross-border cooperation.15x European Commission 2017, p. 14. In order to resolve the institutional obstacles regarding cross-border cooperation, the European Grouping for Territorial Cooperation (EGTC) has been introduced.16x Reg. (EC) No 1082/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July 2006 on a European grouping of territorial cooperation (EGTC). This is an EU legal instrument to facilitate and promote cross-border and transnational cooperation through the establishment of a common legal entity – the EGTC. To support cross-border projects and cooperation in a financial way, the Interreg programme has been introduced, funded through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).17x European Commission. Interreg: European Territorial Cooperation, available at https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/cooperation/european-territorial/. In the 2021-2027 Interreg programme a special objective has been added – ‘A better cooperation governance’, aiming at among others to resolve legal and administrative obstacles in border regions.18x Art. 14 Reg. (EU) 2021/1059 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2021 on specific provisions for the European territorial cooperation goal (Interreg) supported by the European Regional Development Fund and external financing instruments.

I Types

While European support to the institutionalization of cross-border cooperation has grown, border obstacles to mobility and cooperation persist – they are felt most urgently in the EU’s internal border regions. A considerable share of the border difficulties is rooted in legal and administrative frameworks.19x Ibid., p. 8. The next step would thus be to overcome the legal and administrative obstacles. A study conducted for the European Commission in 2017 has mapped and well-illustrated the extent and nature of such legal and administrative obstacles in EU border regions.20x Pucher, J., Stumm, T., & Schneidewind, p. (2017). Easing Legal and Administrative Obstacles in EU Border Regions, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. The authors inventoried and analysed as many as 239 legislative and administrative obstacles, categorizing them into three distinct types:

EU-related legal obstacles: caused by the specific status of an EU border or by EU legislation (or the implementation thereof), where the EU has exclusive or shared competency;

Member State-related legal obstacles: caused by different national or regional laws, where the EU has no competence at all or has only limited competence;

Administrative obstacles: caused by non-willingness, asymmetric cooperation or lack of horizontal coordination, or by different administrative cultures or languages.

It is thus important to note that cross-border obstacles are not only caused by national derogations and differences but also by the EU itself. EU-related legal obstacles are diverse and could be caused by the specific status of an EU border, or by EU legislation (or implementation thereof), where the EU has exclusive or shared competency.21x Ibid., p. 34. In this regard, it has to be mentioned that implementation cannot be fully separated from legislation. Implementation is closely connected to and affected by the way legislation is set up and whether it provides certain flexibility to the Member States (especially in the case of directives). On the other hand, differences in the implementation of EU law and a certain mismatch in a cross-border region can be also seen as a cause of national priorities. Nevertheless, the EU can take more responsibility through accompanying EU-level action promoting a more coordinated implementation across Member States.22x Ibid., p. 39.

While the EU-related obstacles were found less frequent in overall terms, compared to Member States-related legal and administrative obstacles, the effect of EU-related obstacles could however affect multiple cross-border territories at the same time.23x We note that some of these obstacles can also be experienced on transnational level, for example, outside the Euregional territorial scope, but are presumably most significantly present in cross-border regions due to the higher level of integration and mobility. EU regulation can thereby in itself potentially hamper or insufficiently support the aim of Article 174 TFEU to promote territorial cohesion and development, including cross-border regions. In the worst case, it may cause an effect that can impede the goals of EU policy.24x As can be illustrated by the case examples.

The so-called ‘b-solutions’ initiative, supported by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy (DG Regio), is concerned with collecting and analysing legal and administrative obstacles with respect to the three categories above along the EU internal borders. Introduced by the Commission in its Communication of 201725x European Commission 2017, p. 7. and managed by the Association of European Border Regions (AEBR), the initiative aims to gather cases with societal stakeholders and analyse them through a network of external experts.26x See more: www.b-solutionsproject.com/. The authors have analysed several b-solution cases, as well as having a growing range of concrete obstacles through the annual ITEM Cross-Border Impact Assessment, in which legislative proposals are assessed on cross-border effects.27x More elaboration under Section C. These provide examples of the wide range of cases, where cross-border regions, society, governmental institutions and business are confronted with diverse obstacles to free movement, cross-border cooperation and cross-border development. In the next two sub-sections, two examples will be provided. The first illustrates how EU legislation is taking insufficiently into account the cross-border dimension and, notably, the realities of cross-border regions. The second is an example of how the implementation of EU legislation by Member States can cause obstacles or hinder or largely negate the overall aim of EU policy.II Case: Social Security for Cross-Border Workers

Regulation (EC) 883/200428x Reg. (EC) No. 883/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the coordination of social security systems. and Implementing Regulation (EC) 987/2009 lay down conflict rules on the coordination of social security systems of the Member States. While the design of social security systems is the competence of the Member States, the coordination between systems has to be organized on European level “to guarantee that the right to free movement can be exercised effectively”.29x Rec. 45 Reg. 883/2004. The social insurance obligation can only fall on one Member State; that is, only one national legislation will be applicable in cross-border situations. Regulation 883/2004 is furthermore aimed at safeguarding the equal treatment, for example, of frontier workers.30x Rec. 8 Reg. 883/2004. To do so, the competent Member State is determined by the coordination rules of Regulation 883/2004, if a person is or has been subject to the legislation of one or more Member States.31x Art. 2(1) Reg. 883/2004.

There are many examples, however, which show that the coordination rules can be troublesome or even not really fit for purpose in cross-border regions, such as working from home by cross-border workers.32x Derived from b-solutions 2021 and ITEM Cross-Border Impact Assessment 2021: Weerepas, M. (2021). Corona pandemic and home office: consequences for the social security and taxation of cross-border workers, available at www.aebr.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/34_Report-GrenzInfoPunkt.pdf; Weerepas, M., Mertens, P., & Unfried, M. (2021). Impact Analysis of the Future of Working from Home for Cross-Border Workers after COVID-19, ITEM Cross-Border Impact Assessment 2021, Maastricht: ITEM.

Both employees and employers aspire to work more often from home, even after COVID-19, and also policymakers are introducing policies to foster working from home. For cross-border workers this means that, with working from home, the workplace is (partly) transferred from the state of employment to the state of residence. Part-time home-office arrangements imply that the cross-border worker in fact performs work in two or more Member States, as a result of which different coordination rules must be applied.33x Art. 13(1)(a) of Reg. 883/2004 in conjunction with Art. 14(8) of Reg. 987/2009. Consequently, in case more than 25% of the working time and/or salary is spent or obtained in the state of residence, the legislation of the state of residence becomes the applicable social security regime (shifting away from the state of employment). In practice, this is the case when an employee works more than one day a week at home under a fulltime employment contract.

Such a shift in social security system may have far-reaching consequences for both the employee and the employer. The employer can be confronted with higher contributions, to be paid in a different Member State and, accordingly, an increased administrative burden by dealing with a foreign social security system. The employee will no longer be insured in the state of work, but only in the state of residence. This, too, may result in changed contribution rates and even entitlements due to the shift of health insurance, statutory pension accrual, and risk a disconnection between the statutory and the non-statutory benefits, for example, as laid down in collective labour agreements, social security and so on.34x See Weerepas, Mertens, & Unfried 2021 for a complete overview of consequences. During the COVID-19 crisis, these consequences became visible and have been temporarily neutralized by unilateral exemption policies recognizing the impact as force majeure. It is likely that before the pandemic the policymakers did not perhaps view these consequences with the seriousness they deserve.

In this light, it can be argued that the so-called conflict rules of Regulation 883/2004 are not fit for purpose. Instead of fostering free movement and safeguarding the rights of mobile persons, it can – particularly in border regions – prevent people from crossing the border in certain situations or being active across the border. Fabricating practical solutions to such border obstacles are often possible in an ex post manner.35x Even if also these may require considerable time and commitment to materialize. See the three publications in footnote 27. From a legislative point of view, it would be much more interesting to explore how such counterproductive legal-administrative border effects could possibly be prevented or better mitigated in advance, provided those effects would have been known by the EU legislator upfront.III Case: GDPR

The General Data Protection Regulation entered into force in 2018 with the objective to create a harmonized framework for processing data across Europe. An explicit aim is the free flow of data across borders.36x Rec. 3 and 9 GDPR. Nevertheless, in Euregional research, obstacles were experienced, most notably those caused by the GDPR and the diverging national transpositions thereof.37x Schneider, H., Mertens, P., and Unfried, M. (2021). Applying the GDPR in national legislation in cross-border public health cooperation, available at www.aebr.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Report_16.pdf. The Euregio Meuse-Rhine (EMR) is one of the oldest Euroregions in Europe – a shared administrative structure linking five partner regions and three countries (Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands) with three official languages (German, French, and Dutch).

Despite the choice of a regulation as a legal instrument to achieve these goals, the GDPR still leaves room for Member States to legislate in some areas and apply further specifications in other areas.38x European Commission (2020). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: Data protection as a pillar of citizens’ empowerment and the EU’s approach to the digital transition – two years of application of the General Data Protection Regulation, COM(2020) 264 final. It is therefore no surprise that it has been observed almost anonymously that the landscape of privacy regulations in the EU remains very fragmented nonetheless.39x Becker, R., Thorogood, A., Ordish, J., & Beauvais, M.J. (2020), COVID-19 Research: Navigating the European General Data Protection Regulation. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020;22(8):e19799. https://doi.org/10.2196/19799. A recent study40x EUHealthSupport Consortium (2021). Assessment of the EU Member States’ rules on health data in the light of GDPR, available at https://ec.europa.eu/health/system/files/2021-02/ms_rules_health-data_en_0.pdf (pp. 73, 144). concluded critically that “Member States are extensively utilising the margin of manoeuvre afforded in the GDPR” and “its implementation has led to a fragmentation of the law which makes cross-border cooperation for care provision, healthcare system administration or research difficult”.41x Ibid., p. 11.

In its Communication, ‘A European strategy for data’,42x European Commission (2020). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: A European strategy for data, COM(2020) 66 final. the Commission now aims to improve the processing of personal data, including cross-border research. In this case, it becomes evident that the pertinent piece of European legislation would have benefitted from a (more) targeted impact assessment of the law’s anticipated cross-border effects prior to its adoption. Providing flexibility to the Member States comes with a certain price, in this case fragmentation in cross-border situations. EU policymakers could be better informed and could have mitigated or even prevented such undesirable border obstacles in advance, for example, through guiding documents for the Member States promoting a more coordinated implementation.43x Also recommended by Pucher, Stumm, & Schneidewind 2017 with respect to EU-related obstacles. -

C Cross-Border Impact Assessment

As the previous section has shown, cross-border territories have to grapple with consequences of European and national legislation, policies or programmes that have potential negative or positive effects on, for instance, cross-border cooperation, cross-border economic development or the rights and the freedom of cross-border workers. Given the sizeable economic potential of border regions and their innate capacity to act as testing grounds for European integration at large, there is a need for improving and institutionalizing the assessment of (cross-)border effects of legislation and administrative regulations. At best, a cross-border dimension could be streamlined in the standard regulatory impact assessments conducted by the EU as well as national administrations. In Section C.I, the methodology and practice for the annual regulatory impact assessment developed by ITEM will be presented.44x See also Unfried, M., & Kortese, L. (2019). Cross-border impact assessment as a bottom-up tool for better regulation. In Beck (ed.), Transdisciplinary Discourses on Cross-Border Cooperation in Europe. Brussels: Peter Lang, pp. 463-481.45x Unfried, M., Kortese, L. & Bollen-Vandenboorn, A. (2020). ‘The Bottom-up Approach: Experiences with the Impact Assessment of EU and National Legislation in the German, Dutch and Belgian Cross-border Regions. In Medeiros (ed.). Territorial Impact Assessment, Advances in Spatial Science. Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing, pp. 103-121. Subsequently, Section C.II will outline the approach of the Dutch government that has made cross-border impact assessment a compulsory quality element of their general impact assessment framework implementing the methodology earlier described.

I A Bottom-Up Method of Regulatory Impact Assessment

Since 2016, ITEM has conducted cross-border impact assessments of legislative proposals issued by the EU, as well as by the Dutch, Belgian and the German governments. The primary aim is to contribute to the academic debate by providing an innovative tool for regulatory territorial impact assessment, specifically designed for cross-border territories. At the same time, the cross-border impact assessment is also to provide a valuable resource of applied research for policymakers at the regional, national and European levels when they make decisions concerning border regions, contributing to the political debate and evidence-based law-making.46x In fact, this methodology has already been considered as a good practice for EU border regions by DG Regio European Commission 2017, p. 8. Meanwhile, it also often features in Dutch governmental reports on cross-border cooperation. For example, Kamerbrief over Voortgang grensoverschrijdende samenwerking van de Staatssecretaris Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninklijke Relaties van 9 maart 2020, 2020-0000119834.

Considering the large number of (cross-)border regions and the diversity of their characteristics, there is only so much that European- or national-level impact assessments can map. This gives rise to the need for supplementary small-scale and bottom-up Cross-Border Impact Assessments conducted by competent actors in specific border regions. These in-depth border-specific impact assessments may, in turn, contribute to, or rather complement, national and European evaluations by adding the viewpoint on the cross-border impact of legislation and policy.

This approach observes the general distinction between impact assessment and policy evaluation described by the OECD.47x OECD (2014). What is impact assessment? Working Document based on OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation (2014), ‘Assessing the Impact of State Interventions in Research – Techniques, Issues and Solutions’, unpublished manuscript, at 1. Retrieved from www.oecd.org/sti/inno/What-is-impact-assessment-OECDImpact.pdf. This distinction implies that an impact assessment focuses on the prospective effects of the intervention, that is, what the effects might be. Meanwhile an evaluation is rather likely “to cover a wider range of issues […] and how to use the experience from this intervention to improve the design of future interventions”.48x Ibid. Consequently, when a cross-border impact assessment features an ex post analysis of legislation, the assessment is often confined to the question of the legislation’s intended as well as unintended effects. The methodology’s main interest, however, lies in the ex ante assessment of the effects of legislative proposals. It creates the opportunity for contributing evidence-based insights to the legislative process where they can be most powerful. In the best-case scenario, such an ex ante assessment can help to reshape a law in the making to mitigate its potentially obstructive (cross-)border effects.

The methodology relies on two core steps to set up the appropriate assessment framework for analysing border effects. The first step is the need to demarcate the research geographically by defining the relevant (cross-)border region under examination, since it represents a territorial impact assessment. The second step is the outlining of the framework of assessment. This is a table of indicators which are identified based on the underlying fundamental (legal) principles at hand and which serve to measure potential border effects on a set of predefined benchmarks.1 Demarcating the Cross-Border Territory

Regarding the definition of the cross-border territory, as indicated above, two perspectives ought to be distinguished here. The first one defines the objective of an assessment of border effects. These are assessed from a national point of view, meaning effects with an impact on own national territory located at the border. The second adds an essentially new perspective – measuring effects on cross-border regions or cross-border territories where effects can be overall positive for the entire cross-border situation even if certain parts within one Member State could benefit less. In theory, taking a cross-border perspective could even mean that negative effects on one part of the cross-border territory (affecting only parts of one Member State) were compensated by the overall positive effects on the entire territory. Hence, appreciation of the difference between effects on single-border regions (as a national category) and effects on cross-border territories (as a bi- or multi-national category) is vital for assuming a true cross-border perspective.

Depending on the nature of the dossier, the territorial scope could be the territory as the entire border between two countries or all Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics – NUTS 2 or NUTS 3 areas at the border. Another option is to use the geographical boundaries of an existing Euregion or the territories as defined in the Interreg programmes.49x As set out in the introduction, in the article an argument can be made in favour of Euregions.2 Research Themes, Principles, Benchmarks and Indicators

Next, the potential effects of certain legislative proposals or measures are assessed using certain themes, questioning ‘impact on what?’ Cross-border effects come in many shapes and forms; it does not solely impact socioeconomic aspects of development “but also […] environmental, governance and […] the territorial articulation of the border regions”.50x Medeiros, E. (2016). 20 Years of INTERREG-A in Inner Scandinavia, online English version, Hamar, available at https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/evidence-and-data/report-territorial-impact-assessment-cross-border-cooperation-programmes, p. 64. Their assessment, therefore, requires a holistic approach, whereby three overarching themes help to pinpoint the relevant border effects of certain legislation.

The European integration theme concerns the potential impact of policies on individuals living and working in cross-border regions. It questions whether legislative proposals (or existing laws) promote or limit the life of citizens in a cross-border territory in terms of the basic principles of European integration and free movement.51x As laid down in the Treaties or in EU legislation, such as citizenships rights, non-discrimination, and so on. For instance, the EU coordination rules on social security complicate cross-border working for both frontier workers and their employers, as the potential administrative and financial effects of imminent switches in the applicable national legislation may deter from using free movement rights.

The theme of socioeconomic/sustainable development focuses on the functioning and development of the cross-border and Euregional economy and labour market. The theme concentrates on the territorial development as stipulated in Article 174 TFEU. From this perspective, it becomes clear that the cross-border effects of Regulation 883/2004 (as described above) can hinder the development of a true cross-border labour market and limit cross-border labour and the economic growth potential of the cross-border territory.

The theme of Euregional cohesion refers to the assessment of border effects on the cross-border cooperation and mind-set between institutions, citizens and business contacts. Such aspects play an important role in the assessment of the relationships between the institutions and cross-border governance of Euregions and the Euregional identity of citizens. These effects are hardly measurable in a quantitative way. Impact on the quality of cooperation or a specific governance structure has to be assessed qualitatively with the help of experts.

Depending on the specific dossier, the effects may be evaluated for all themes or only one or two of them. Key in the assessment of each theme is to find appropriate principles and benchmarks. Principles refer to the legal and policy aims, for example, established in European legislation or by Euregional administrations. These can be derived from the treaties and/or the specific aims of the assessed policy or legislation. Benchmarks are standards of comparison that emanate from these principles. They provide criteria that describe how the ideal situation would look like. Finally, the indicators are measurement units for interpreting the consequences of legislation based on the predefined benchmarks;52x In the Annex, Table 1 provides some examples for each of these steps in the assessment framework. sometimes, for quantitative measuring, such as the financial impacts, and sometimes for qualitative measuring, such as exposing the impact of legislations on the cooperation of public entities across the border.53x An overview of the topics of past Cross-Border Impact Assessment ‘dossiers’ can be found in the Annex or online at www.maastrichtuniversity.nl/research/item/research/item-cross-border-impact-assessment.

Admittedly, one of the crucial problems of the assessments has been the lack of cross-border data in many policy fields. Thus, next to offering an in-depth legal analysis of the cross-border situation, the assessment often has to produce its own data. To do so, part of the work (also in other border regions) is to produce surveys, carry out qualitative interviews and, in particular, rely on expert judgements. In this respect, the network of practitioners and experts dealing with cross-border issues is vital to the entire approach of the impact assessment. However, it is also an important argument for the improvement of cross-border data on the national and European levels.54x See also van der Valk, J. (2019). Cross-Border Data, ITEM Cross-Border Impact Assessment 2019, Maastricht: ITEM. This issue has also been raised by the European Court of Auditors regarding Interreg55x European Court of Auditors (2021). Interreg cooperation: The potential of the European Union’s cross-border regions has not yet been fully unlocked, Special Report 14/2021. and taken up by DG Regio as action.56x European Commission 2021b, p. 7.II Regulatory Border Impact Assessments by the Dutch Government

The latest OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook (2021) shows that wherever national governments have established solid regulatory impact assessment, the impacts on competition, environment and the public sector are the ones that are most frequently assessed. The territorial dimension is among the least assessed types of impact.57x OECD (2021). OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2021, Paris: OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/38b0fdb1-en. See Figure 2.15. This was also shown in earlier publications of the OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook, for instance in 2018, making clear the structural nature of the gap. Moreover, until recently, there was no national government in the EU that integrated explicitly the assessment of cross-border effects into their particular framework of regulatory impact assessments. Since 2021, the Dutch government was the first EU Member State government to have developed and introduced a tool and obligation to this end.58x European Commission 2021b, p. 15. This is an important turning point and a promising example of how Member State-related cross-border obstacles may be prevented or reduced, as there is an important role for the national level in this regard.59x Pucher, Stumm, & Schneidewind 2017, pp. 19, 30.

The Dutch government has developed over the past decades a long list of compulsory regulatory impact assessments, including the effects on administrative burden, business and the environment.60x The full list of obligations can be found on the homepage of the Ministry of Justice and Security, available at www.kcwj.nl/kennisbank/integraal-afwegingskader-beleid-en-regelgeving/verplichte-kwaliteitseisen. The requirements and instructions for ex ante regulatory impact assessment are bundled in the ‘Integrated Impact Assessment Framework’ (Integraal Afwegingskader; IAK). The IAK consists of multiple questions that need to be answered, aiming to safeguard that all relevant decision information is in view and available resources have been consulted. It is therefore the Dutch framework for impact assessment and promotion of including evidence in the law-making process. In 2021, the assessment of effects on border or cross-border regions (grenseffecten) was made an additional compulsory requirement of the IAK. This means the Dutch framework now includes the (cross-)border effects assessment as a quality requirement in the overall national assessment scheme on legislative impact. The Ministry of Interior and Kingdom Relations is the responsible and coordinating institution, also supporting the line ministries.

This ‘border effects check’ is carried out in a step-by-step manner, in order to minimize the administrative burden for line ministries. It includes both a quick scan and (external) assistance for in-depth analysis. The quick scan allows for screening the possible effects and to come to a more concrete idea of the nature, sort and scope thereof. The questions included are based on the themes and principles as mentioned in the previous section. Subsequently, on the basis of the quick scan, it can be determined whether in-depth research is required and/or the impact has to be examined by (external) (EU)regional and/or academic experts and practitioners. Finally, based on the specification and examination, line ministries can weigh the effects. Central questions include whether the effects are really significant and whether they give clues to help us come up with ideas on dealing with them. Ideally, the line ministries should start going through the quality requirement as early as possible in the legislative process, that is, as soon as the intention for a new policy or regulation takes shape. This offers the best chance of the results playing a serious role in the policy consideration and of alternatives being included. However, since the obligation is relatively new, the effective implementation at the departments is still ongoing. -

D Cross-Border Impact Assessment within EU Policymaking

The previous sections have established the need for giving a special focus on legislative effects in (cross-)border regions and the need for a bottom-up approach from a regulatory perspective. They have further highlighted adopting a territorial scope in analysis and evidence collection that helps to grasp the (potential) conflict of laws and other border effects in a given border space through regulatory impact assessment. This can be done – as shown in Section C – by independent assessments of regulatory proposals by experts in the border regions and incorporated into the assessment routine of a national government in the course of the law-making process. An important next question is how the study of cross-border impact assessments be scaled up to general use on a European scale. Indeed, EU-related obstacles should be best addressed on the EU level.61x Pucher, Stumm, & Schneidewind 2017, p. 20; European Commission 2021a; European Commission 2017.

While the European Commission has been sophisticating its Better Regulation toolbox for more than two decades, attention to assessing the territorial impact of policy and legislation is more recent. Yet, the practice of territorial impact assessments is still encountering some practical challenges and may be in need of refinement as to the recognition and embracement of the cross-border dimension.I Territorial Impact Assessment in EU Policy

The European Commission defines ‘Territorial Impact Assessment’ as the procedure (or method) to

evaluate the likely impact of policies, programmes and projects on the territory, highlighting the importance of the geographic distribution of consequences and effects and considering the spatial developments in Europe.62x This definition can be found on DG Regio’s homepage under the heading ‘Territorial Impact Assessment’, available at https://ec.europa.eu/knowledge4policy/territorial/topic/regional_en.

Increasingly recognizing the importance of territorial impact, the Commission has factored this dimension into its own impact assessment framework. In its ‘Better Regulation Package’ of 2015, the Commission proposed instruments to ensure that territorial aspects are factored into policy options.63x Whereas the European Commission’s ‘Better regulation for better results – An EU agenda’ Communication, COM(2015) 215 final of 19 May 2015 does not explicitly mention the territorial dimension, it is described in Chapter III of the ‘Guidelines on impact assessment’ on page 31. See: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-making-process/planning-and-proposing-law/better-regulation-why-and-how/better-regulation-guidelines-and-toolbox_en. In the Communication of 2018, it emphasized the wish to “[a]mend its better regulation guidance to highlight the importance of screening and assessing territorial impacts”.64x European Commission (2018). Communication from the Commission: The principles of subsidiarity and proportionality: Strengthening their role in EU policymaking, COM(2018) 703. As part of the Impact Assessment toolbox, the EU executive has also described how to assess territorial impacts under ‘tool 33’.65x The toolbox can be found here: https://ec.europa.eu/info/files/better-regulation-toolbox-33_en.

However, the relevant tools already at the Commission’s disposal appear somewhat hampered in their application by practical problems at the EU level. Importantly, to start with, Territorial Impact Assessment (TIA) is still a non-mandatory procedure,66x Medeiros 2016, p. 97. as opposed to, for instance, Environmental Impact Assessment. Another concern raised is when a TIA would be relevant and how to identify relevant dossiers. In practice, it became clear that the so-called tool 33 within the Better Regulation Package of the Commission has not been applied in many legislative proposals and, even not at all, during the COVID-19 pandemic.67x European Commission 2021b, p. 15.

Regarding the specific cross-border perspective, moreover, it is important to note that the European Commission has most recently recognized the needs of cross-border territories in strengthening the territorial dimension in the impact assessment.68x European Commission 2021a, p. 15. Two issues are relevant here. On the one hand, a 2016 study commissioned by the European Commission highlights the needs of border regions according to their particular features and shows the extent to which border regions differ from one another.69x SWECO et al. (2016). Collecting solid evidence to assess the needs to be addressed by Interreg cross-border programmes: Final Report, Publications Office, 2016, available at https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2776/13983. In view of these myriad border regions in the EU, mapping detailed cross-border effects for all the EU’s cross-border regions in its standard impact assessments seems difficult for an EU institution with rather limited resources. On the other hand, it is not always obvious that the necessary data exist to allow a comprehensive assessment. Adequate data at regional level already might be a challenge, but what is even more challenging is the non-availability of cross-border data that, even when they are available, are barely adequate. Therefore, the initiatives of, for example, European Cross-border Monitory Network70x www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/EN/research/specialist-articles/spatial-development/eu-council-presidency/network-crossborderdata/main.html. and the mere concrete realization of the first cross-border dataset on the labour market between the Netherlands, Germany and Belgium, Grensdata,71x https://grensdata.eu; this dataset is the result of two Interreg projects, being ‘Arbeidsmarkt in grensregio’s DE-NL’ and ‘Werkinzicht’. The data are focused upon cross-border labour data. could and should be encouraged.72x As also expressed in European Commission 2021b.II EU Cross-Border Impact Assessment for Better Regulation

Given these practical concerns, one might wonder whether the EU executive (alone) is actually the right actor for conducting cross-border impact assessments on a European scale. Insights from national level may be instructive here. Especially the Dutch experiences in the framework of grenseffecten with the methodology and gathering of evidence on cross-border effects within the process of law-making might be relevant for other Member States as well as the EU.73x As it is also under the attention of the Commission, European Commission 2021b, p. 15.

As indicated above, conducting in-depth and border-specific impact assessments may be difficult at the European and even at the national level due to the great differences that exist among European border regions. Each (cross-)border region is characterized by a peculiar mix of intersecting national laws and other factors depending on its geographical location. In light of such complications, a bottom-up approach to cross-border impact assessment actually seems the only feasible one. As also indicated by the Commission, the lack of data and the diversity of regions make it even more important to have active engagement of local and regional authorities in consultation processes.74x European Commission 2018. In fact, the EU’s Territorial Agenda 2030 expressly stimulates the involvement of multiple stakeholders and the place-based approach:The place-based approach to policy making contributes to territorial cohesion. It is based on horizontal and vertical coordination, evidence-informed policy making and integrated territorial development. It addresses different levels of governance (multi-level governance approach) contributing to subsidiarity. It ensures cooperation and coordination involving citizens, civil society, businesses, research and scientific institutions and knowledge centres.75x Territorial Agenda 2030: a future for all places, p. 4, available at https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/brochure/territorial_agenda_2030_en.pdf.

Accordingly, a multilevel governance approach may be key to the maturation of the TIA practice and especially the inclusion of studying cross-border effects, as elaborated in Section C.I.

The European Committee of the Regions (CoR) is one such stakeholder, where the local and regional authorities across the EU are represented. The CoR has also some experience with the development of TIAs, as it has been conducting these on several EU dossiers over the past couple of years.76x See, for example, European Committee of the Regions (2021). Territorial Impact Assessment Zero Emission Vehicles, available at https://cor.europa.eu/en/engage/studies/Documents/TIAZeroEmissionsCars.pdf. Still, though, following the methodology of the ESPON TIA tool,77x www.espon.eu/main/Menu_ToolsandMaps/TIA/. the assessment is less focussed on identifying and assessing cross-border effects.78x See also the comparison of assessment tools in Medeiros, E. (ed.) (2020). Territorial Impact Assessment, Advances in Spatial Science. Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing. Importantly, the CoR also recently launched the Regional Hubs Network, where the implementation of EU policies is being monitored.79x https://cor.europa.eu/en/our-work/Pages/network-of-regional-hubs.aspx. This refers in the first place to an assessment of existing EU legislation ex post, that is, analysed by experts in different regions with respect to their experiences at the regional level. The ‘RegHub’ Network currently includes 46 member-regions, 10 observers and 1 associated body. It is also recognized as an established subgroup of the European Commission’s Fit for Future Platform.80x See also https://cor.europa.eu/en/our-work/Pages/network-of-regional-hubs.aspx, retrieved on 24 March 2022. An ex ante assessment does not exist at the moment.

This interregional platform may provide a useful starting point. The CoR already fulfils a consultative role, as further strengthened by the Lisbon Treaty, in the EU legislative process to consider regional and local dimensions before new legislative acts are proposed. The new network could well be used for gathering opinions and assessments from experts of various regions across Europe. Hence, the CoR could also establish a special network or subgroup of border regions dedicated to assessing the border effects of legislation at the EU level.

Such an ex ante cross-border assessment would be an added value. The existing AEBR and the several Euregions across Europe could be closely involved as cross-border actors to strengthen their perspective in the decision-making process.

While a quick scan can, for example, be made with regional and local actors, more in-depth analysis could be supported by the expertise of research and knowledge institutions. Across Europe, relevant cross-border expertise centres have gathered in the so-called TEIN network.81x https://transfrontier.eu. See also, the ITEM-TEIN study ‘The impact of the Corona crisis on cross-border regions’, ITEM Cross-Border Impact Assessment 2020, dossier 1, available at https://itemcrossborderportal.maastrichtuniversity.nl/link/id/LqvDtWt9bnE0Hfxd. Also, the network within the b-solution process can here be of relevance as well as DG Regio’s Border Focal Point.82x https://futurium.ec.europa.eu/en/border-focal-point-network; an online platform that has been set up by DG Regio to discuss border obstacles and exchange experiences. -

E Conclusion

This article has addressed the need and relevance of Cross-Border Impact Assessment to improve evidence-based policymaking, legislative procedure and implementation for (cross-)border regions through a multilevel governance approach. This special variation of the TIA may provide an opportunity for studying potential (cross-)border effects emanating from legislation systematically at the European level. In a multilevel governance system, there is certainly the need for assessments at all levels, enabling to address all categories of cross-border obstacles.83x Pucher, Stumm, & Schneidewind 2017.

A method for conducting assessments at the regional level focusing on the conditions in particular cross-border territories has been addressed, capturing border effects in three themes. The Netherlands has introduced the first cross-border approach in its regulatory assessment framework to reduce national-related obstacles. In addition, the article highlights that the EU has an important role to play in extending support to the efforts of the local, regional and national levels in the EU Member States and to improve the EU policymaking itself by an improved TIA/CBIA and better guidance on the transposition of directives.84x Ibid., p. 30. Indeed, EU-related obstacles can be best mitigated on the EU level in the first place.

On the EU level, the introduction of cross-border impact assessments would be a logical follow-up to other initiatives already undertaken by the European Commission in the framework of its impact assessment and Better Regulation strategy. In the wisdom of ‘prevention is better than cure’, the ex ante assessment on cross-border aspects is not a luxury but rather a necessity. However, complicating factors for adding a cross-border dimension to the Commission’s TIA – notably, the vast regional diversity and lack of cross-border data – highlight the need for capacity building at the level of border regions throughout the EU. If regions, municipalities and cross-border organizations like Euregions and Eurodistricts invest in cross-border assessments, they could in the future influence national and EU policy in a more evidence-based manner. The CoR could potentially play an enabling role in this. With the exclusive know-how and the perspective from a particular cross-border territory, regional actors can provide important evidence of cross-border effects. Thus, both the incorporation of cross-border effects into the assessment routines within the process of law-making and the independent knowledge production with the expertise of stakeholders in the cross-border territories from a real cross-border perspective are needed.

Including the cross-border dimension into the standard impact assessment methodology at the national and EU levels may result in an essential addition and raise awareness85x For example, consider the impact of new political initiatives on making working from home structural for cross-border workers. and enhance an evidence-based approach to the legislative process. The resulting legislation may consequently be more susceptible to the needs of (cross-)border regions and their inhabitants.

AnnexTable 1 provides examples of principles, benchmarks and indicators for the Cross-Border Impact Assessment.

Table 1 Examples of Principles, Benchmarks and IndicatorsThemes Goals/principles Good practice/benchmark Indicators European integration European integration, European citizenship, non-discrimination No border controls, open labour market, easy recognition of qualifications, good coordination of social security facilities and taxes Number of border controls, cross-border commuting, duration and cost of recognition of qualifications, access to the housing market, and so on Socioeconomic/Sustainable development Regional competitive strength, sustainable development cross-border territory Cross-border initiatives for establishing companies, Euregional labour market strategy, cross-border spatial planning At Euregional level: GDP, unemployment, quality of cross-border cluster, environmental impact (emissions), poverty Euregional cohesion Cross-border cooperation/good governance, Euregional cohesion Functioning of cross-border services, cooperation with organizations, coordination procedures, associations Number of cross-border institutions, the quality of cooperation (in comparison with the past), development of Euregional governance structures, quantity and quality of cross-border projects Own compilation

Tables 2 and 3 depict the dossiers of the previous two impact assessment cycles

Table 2 Themes of the Cross-Border Impact Assessment 2020No. Subject Specification Dossiers 1. The impact of the Corona crisis on cross-border regions (TEIN study) This research was conducted to assess the effects national approaches towards crisis response and cross-border coordination during the Corona crisis have had on cross-border regions. 2. Implementation and possible effects of the Dutch Strategy on Spatial Planning and the Environment (NOVI) from a Euregional perspective The Netherlands created NOVI as a long-term vision on the future and development of the quality of life (leefomgeving) in the country. This research assessed the effects of this new strategy on the Euregions and their residents. 3. Ex ante evaluation of the (potential) cross-border impact of the structural reinforcement programme to end coal-based power generation in Germany (Kohleausstieg) As Germany plans to end coal-based power generation, ITEM assessed the potential impact such a structural change could have on the historically coal-dependent Rhineland region. 4. The (im)possibility of cross-border training budgets to tackle long-term unemployment This research assesses the feasibility of cross-border training for jobseekers by evaluating the legislative impact in the SGA policy (service desks for cross-border job placement). 5. The cross-border effects of the proposed German ‘basic pension’ (Grundrente) This dossier examines what effect a basic pension in Germany would have on frontier workers working in Germany. 6. The cross-border effects of decentralization in social security: case study on Dutch youth care Since 2015, youth care in the Netherlands became a municipal responsibility. This dossier assesses the impact of this change on cross-border regions. Table 3 Themes of the Cross-Border Impact Assessment 2021No. Subject Specification Dossiers 1. Ex ante study on the cross-border effects of the EU’s proposed Minimum Wage Directive (TEIN study) This dossier assesses the possible impact a (binding) common European framework for minimum wages would have on cross-border regions and their inhabitants. The research includes regions located in Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Poland. 2. Ex post analysis into the future of working from home for cross-border workers post-COVID-19 This dossier analyses the effects a formal homeworking policy created during the COVID-19 crisis would have on cross-border workers and their employers in the future. 3. The effects of national Corona crisis management on cross-border crisis management in the Euregio Meuse-Rhine (follow-up study) This research is a follow-up of dossier 1 written in 2020’s cross-border impact assessment. The research assesses the consequences of national crisis management on cooperation in the cross-border region in regards to various local and regional crisis teams. 4. Is the EU Patients’ Rights Directive fit for providing well-functioning healthcare in cross-border regions? An ex post assessment There were systematic discrepancies between the health systems of Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. This dossier analyses whether or not the EU Patients’ Rights Directive can provide well-functioning healthcare in cross-border regions. Kenniscentrum voor Beleid en Regelgeving. Grenseffecten

Cross-border effects assessment as a new quality requirement in the Dutch ‘Integrated Impact Assessment Framework’ (Integraal Afwegingskader; IAK)

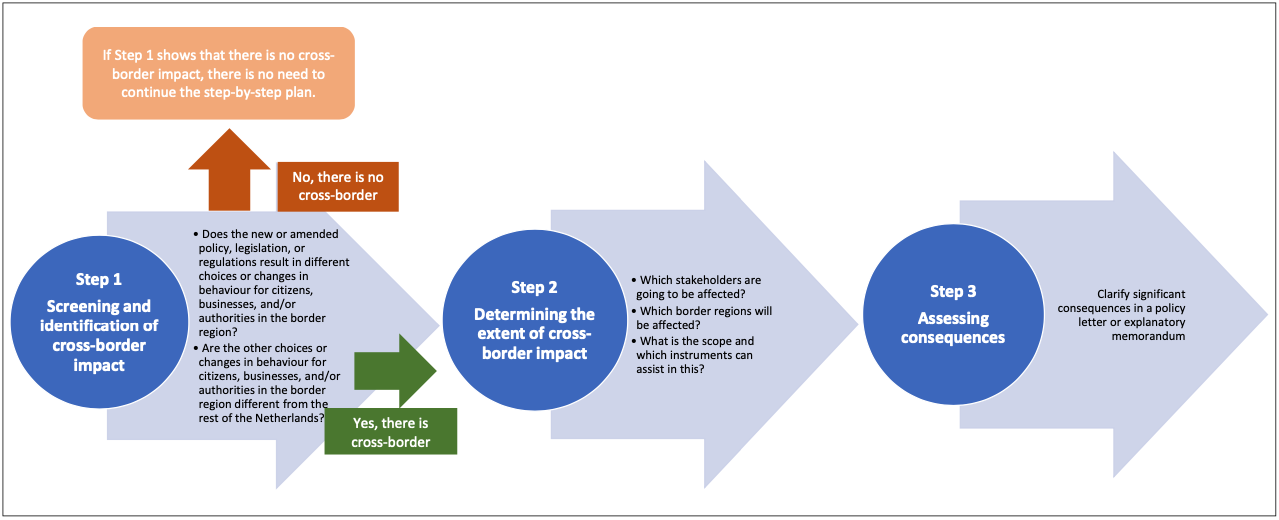

It was the House of Representatives that had been lobbying for years for the introduction of an ex ante review for national legislation and policy initiatives focusing on the Dutch border regions. This was followed by an intensive debate at the working level in the ministries on how to improve the consideration of cross-border effects in the proposals of the various line ministries. The authors were involved in the development of a guidance document for the ex ante border effect assessment that is today available for all line ministries. The flowchart below summarizes the process.

The first step is to screen on the possibility of cross-border effects, because (1) the proposed policy or legislation can affect the free movement of persons, goods and/or capital, and/or (2) it creates a (new or another kind of) difference in that area with (one of) the neighbouring countries. This step has to be done by the different policymakers in the line departments themselves. This is an easy screening exercise and is meant to filter relevant dossiers from the stack. Nevertheless, it is important that there is some ‘border-awareness’ within the different ministries.If the first step results in a possible cross-border effect, the next step is to specify the effect. To do so, a quick scan is developed and provided to the ministries. The quick scan guides them with various questions in order to come to a more concrete idea of the nature, sort and scope of the possible cross-border effect. Here, the coordinating Ministry of Interior plays a supportive role. Furthermore, it is recommended to use help from different stakeholders at the local and Euregional levels, as well as expertise centres. Subsequently, on the basis of the quick scan, it can be determined whether in-depth research is required. Finally, based on the specification in the second step, line ministries can weigh things up. Central questions are whether the effects are really significant and reflect on how to deal with them.

-

1 European Commission (2017). ‘Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament: Boosting growth and cohesion in EU border regions’, COM(2017) 534 final.

-

2 See for example Lambertz, K. (2010). Die Grenzregionen als Labor und Motor kontinentaler Entwicklungen in Europa. Schriften zur Grenzüberschreitenden Zusammenarbeit, Band 4.

-

3 See for example Beck, J. (2018). Cross-Border Cooperation: Challenges and Perspectives for the Horizontal Dimension of European Integration. Administrative Consulting, (1):56-62. Ulrich, P. (2021). Participatory Governance in the Europe of the Cross-border Regions. Cooperation – Boundaries – Civil Society. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

-

4 European Commission (2021a). ‘Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: EU Border Regions: Living labs of European integration’, COM(2021) 393 final.

-

5 Unfried, M. (2020). Cross-border governance in times of crisis: first experiences from the Euroregion Meuse-Rhine. The Journal of Cross-Border Studies in Ireland, No. 15. pp. 87-96. Schneider, H., Kortese, L., Mertens, P., & Sivonen, S. (2021). Cross-border mobility in times of COVID-19: Assessing COVID-19 Measures and their Effects on Cross-border Regions within the EU. EU-CITZEN, available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/eu-citzen_-_report_on_cross-border_mobility_in_times_of_covid-19.pdf.

-

6 This distinction is referring to the categories as described in Klatt, M. (2021). Diesseits und jenseits der Grenze - das Konzept der Grenzregion. In D. Gerst, M. Klessmann, & H. Krämer (Eds.), Grenzforschung: Handbuch für Wissenschaft und Studium(pp. 143-155). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft. Border Studies, Cultures, Spaces, Orders Vol. 3 https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845295305.

-

7 In this sense, the EU category NUTS 3 region, for instance, is the common statistical category. See https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/nuts/nuts-maps.

-

8 The legal basis of the Committee of the Regions is today Art. 13(4) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), Arts. 300 and 305 to 307 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

-

9 The latest and very comprehensive project results were published in 2018 by the University of Barcelona, see: Durà, A., F. Camonita, M. Berzi, & A. Noferini (2018). Euroregions, Excellence and Innovation across EU borders. A Catalogue of Good Practices. Barcelona: Department of Geography, UAB.

-

10 See http://www.espaces-transfrontaliers.org/en/resources/territories/euroregions/.

-

11 Formerly, Art. 158 Treaty establishing the European Community (TEC).

-

12 Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community (2007/C 306/01). The Lisbon Treaty added the emphasis on territorial cohesion, next to social and economic cohesion.

-

13 European Commission (2021b). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and Council, Joining forces to make better laws, available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/files/better-regulation-joining-forces-make-better-laws_en, p. 15.

-

14 See in this regard also Council of Europe (2012). Manual on removing obstacles to cross-border cooperation. Strasbourg, November 2012.

-

15 European Commission 2017, p. 14.

-

16 Reg. (EC) No 1082/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July 2006 on a European grouping of territorial cooperation (EGTC).

-

17 European Commission. Interreg: European Territorial Cooperation, available at https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/cooperation/european-territorial/.

-

18 Art. 14 Reg. (EU) 2021/1059 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2021 on specific provisions for the European territorial cooperation goal (Interreg) supported by the European Regional Development Fund and external financing instruments.

-

19 Ibid., p. 8.

-

20 Pucher, J., Stumm, T., & Schneidewind, p. (2017). Easing Legal and Administrative Obstacles in EU Border Regions, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

-

21 Ibid., p. 34.

-

22 Ibid., p. 39.

-

23 We note that some of these obstacles can also be experienced on transnational level, for example, outside the Euregional territorial scope, but are presumably most significantly present in cross-border regions due to the higher level of integration and mobility.

-

24 As can be illustrated by the case examples.

-

25 European Commission 2017, p. 7.

-

26 See more: www.b-solutionsproject.com/.

-

27 More elaboration under Section C.

-

28 Reg. (EC) No. 883/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the coordination of social security systems.

-

29 Rec. 45 Reg. 883/2004.

-

30 Rec. 8 Reg. 883/2004.

-

31 Art. 2(1) Reg. 883/2004.

-

32 Derived from b-solutions 2021 and ITEM Cross-Border Impact Assessment 2021: Weerepas, M. (2021). Corona pandemic and home office: consequences for the social security and taxation of cross-border workers, available at www.aebr.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/34_Report-GrenzInfoPunkt.pdf; Weerepas, M., Mertens, P., & Unfried, M. (2021). Impact Analysis of the Future of Working from Home for Cross-Border Workers after COVID-19, ITEM Cross-Border Impact Assessment 2021, Maastricht: ITEM.

-

33 Art. 13(1)(a) of Reg. 883/2004 in conjunction with Art. 14(8) of Reg. 987/2009.

-

34 See Weerepas, Mertens, & Unfried 2021 for a complete overview of consequences.

-

35 Even if also these may require considerable time and commitment to materialize. See the three publications in footnote 27.

-

36 Rec. 3 and 9 GDPR.

-

37 Schneider, H., Mertens, P., and Unfried, M. (2021). Applying the GDPR in national legislation in cross-border public health cooperation, available at www.aebr.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Report_16.pdf. The Euregio Meuse-Rhine (EMR) is one of the oldest Euroregions in Europe – a shared administrative structure linking five partner regions and three countries (Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands) with three official languages (German, French, and Dutch).

-

38 European Commission (2020). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: Data protection as a pillar of citizens’ empowerment and the EU’s approach to the digital transition – two years of application of the General Data Protection Regulation, COM(2020) 264 final.

-

39 Becker, R., Thorogood, A., Ordish, J., & Beauvais, M.J. (2020), COVID-19 Research: Navigating the European General Data Protection Regulation. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020;22(8):e19799. https://doi.org/10.2196/19799.

-

40 EUHealthSupport Consortium (2021). Assessment of the EU Member States’ rules on health data in the light of GDPR, available at https://ec.europa.eu/health/system/files/2021-02/ms_rules_health-data_en_0.pdf (pp. 73, 144).

-

41 Ibid., p. 11.

-

42 European Commission (2020). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: A European strategy for data, COM(2020) 66 final.

-

43 Also recommended by Pucher, Stumm, & Schneidewind 2017 with respect to EU-related obstacles.

-

44 See also Unfried, M., & Kortese, L. (2019). Cross-border impact assessment as a bottom-up tool for better regulation. In Beck (ed.), Transdisciplinary Discourses on Cross-Border Cooperation in Europe. Brussels: Peter Lang, pp. 463-481.

-

45 Unfried, M., Kortese, L. & Bollen-Vandenboorn, A. (2020). ‘The Bottom-up Approach: Experiences with the Impact Assessment of EU and National Legislation in the German, Dutch and Belgian Cross-border Regions. In Medeiros (ed.). Territorial Impact Assessment, Advances in Spatial Science. Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing, pp. 103-121.

-

46 In fact, this methodology has already been considered as a good practice for EU border regions by DG Regio European Commission 2017, p. 8. Meanwhile, it also often features in Dutch governmental reports on cross-border cooperation. For example, Kamerbrief over Voortgang grensoverschrijdende samenwerking van de Staatssecretaris Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninklijke Relaties van 9 maart 2020, 2020-0000119834.

-

47 OECD (2014). What is impact assessment? Working Document based on OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation (2014), ‘Assessing the Impact of State Interventions in Research – Techniques, Issues and Solutions’, unpublished manuscript, at 1. Retrieved from www.oecd.org/sti/inno/What-is-impact-assessment-OECDImpact.pdf.

-

48 Ibid.

-

49 As set out in the introduction, in the article an argument can be made in favour of Euregions.

-

50 Medeiros, E. (2016). 20 Years of INTERREG-A in Inner Scandinavia, online English version, Hamar, available at https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/evidence-and-data/report-territorial-impact-assessment-cross-border-cooperation-programmes, p. 64.

-

51 As laid down in the Treaties or in EU legislation, such as citizenships rights, non-discrimination, and so on.

-

52 In the Annex, Table 1 provides some examples for each of these steps in the assessment framework.

-

53 An overview of the topics of past Cross-Border Impact Assessment ‘dossiers’ can be found in the Annex or online at www.maastrichtuniversity.nl/research/item/research/item-cross-border-impact-assessment.

-

54 See also van der Valk, J. (2019). Cross-Border Data, ITEM Cross-Border Impact Assessment 2019, Maastricht: ITEM.

-

55 European Court of Auditors (2021). Interreg cooperation: The potential of the European Union’s cross-border regions has not yet been fully unlocked, Special Report 14/2021.

-

56 European Commission 2021b, p. 7.

-

57 OECD (2021). OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2021, Paris: OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/38b0fdb1-en. See Figure 2.15. This was also shown in earlier publications of the OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook, for instance in 2018, making clear the structural nature of the gap.

-

58 European Commission 2021b, p. 15.

-

59 Pucher, Stumm, & Schneidewind 2017, pp. 19, 30.

-

60 The full list of obligations can be found on the homepage of the Ministry of Justice and Security, available at www.kcwj.nl/kennisbank/integraal-afwegingskader-beleid-en-regelgeving/verplichte-kwaliteitseisen.

-

61 Pucher, Stumm, & Schneidewind 2017, p. 20; European Commission 2021a; European Commission 2017.

-

62 This definition can be found on DG Regio’s homepage under the heading ‘Territorial Impact Assessment’, available at https://ec.europa.eu/knowledge4policy/territorial/topic/regional_en.

-

63 Whereas the European Commission’s ‘Better regulation for better results – An EU agenda’ Communication, COM(2015) 215 final of 19 May 2015 does not explicitly mention the territorial dimension, it is described in Chapter III of the ‘Guidelines on impact assessment’ on page 31. See: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-making-process/planning-and-proposing-law/better-regulation-why-and-how/better-regulation-guidelines-and-toolbox_en.

-

64 European Commission (2018). Communication from the Commission: The principles of subsidiarity and proportionality: Strengthening their role in EU policymaking, COM(2018) 703.

-

65 The toolbox can be found here: https://ec.europa.eu/info/files/better-regulation-toolbox-33_en.

-

66 Medeiros 2016, p. 97.

-

67 European Commission 2021b, p. 15.

-

68 European Commission 2021a, p. 15.

-

69 SWECO et al. (2016). Collecting solid evidence to assess the needs to be addressed by Interreg cross-border programmes: Final Report, Publications Office, 2016, available at https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2776/13983.

-

71 https://grensdata.eu; this dataset is the result of two Interreg projects, being ‘Arbeidsmarkt in grensregio’s DE-NL’ and ‘Werkinzicht’. The data are focused upon cross-border labour data.

-

72 As also expressed in European Commission 2021b.

-

73 As it is also under the attention of the Commission, European Commission 2021b, p. 15.

-

74 European Commission 2018.

-

75 Territorial Agenda 2030: a future for all places, p. 4, available at https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/brochure/territorial_agenda_2030_en.pdf.

-

76 See, for example, European Committee of the Regions (2021). Territorial Impact Assessment Zero Emission Vehicles, available at https://cor.europa.eu/en/engage/studies/Documents/TIAZeroEmissionsCars.pdf.

-

78 See also the comparison of assessment tools in Medeiros, E. (ed.) (2020). Territorial Impact Assessment, Advances in Spatial Science. Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing.

-

79 https://cor.europa.eu/en/our-work/Pages/network-of-regional-hubs.aspx.

-

80 See also https://cor.europa.eu/en/our-work/Pages/network-of-regional-hubs.aspx, retrieved on 24 March 2022.

-

81 https://transfrontier.eu. See also, the ITEM-TEIN study ‘The impact of the Corona crisis on cross-border regions’, ITEM Cross-Border Impact Assessment 2020, dossier 1, available at https://itemcrossborderportal.maastrichtuniversity.nl/link/id/LqvDtWt9bnE0Hfxd.

-

82 https://futurium.ec.europa.eu/en/border-focal-point-network; an online platform that has been set up by DG Regio to discuss border obstacles and exchange experiences.

-

83 Pucher, Stumm, & Schneidewind 2017.

-

84 Ibid., p. 30.

-

85 For example, consider the impact of new political initiatives on making working from home structural for cross-border workers.

European Journal of Law Reform |

|

| Article | Cross-Border Impact Assessment for EU’s Border Regions |

| Keywords | border regions, cross-border cooperation, impact assessment, evidence-based policy, territorial cohesion |

| Authors | Martin Unfried, Pim Mertens, Nina Büttgen en Hildegard Schneider |

| DOI | 10.5553/EJLR/138723702022024001004 |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Abstract Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

Martin Unfried, Pim Mertens, Nina Büttgen e.a. , 'Cross-Border Impact Assessment for EU’s Border Regions', (2022) European Journal of Law Reform 47-67

|

Within the European Union (EU), border regions represent 40% of its territory, and they are home to a third of the EU’s population. The European Commission refers to border regions as ‘Living labs of European Integration’, where both the effects of free movement and remaining obstacles to integration are most visible. These are largely of legal or administrative nature, caused on both national and EU level. As acknowledged in the Commission’s report on Better Regulation, the Impact Assessment of EU policies has to be improved taking into account the perspective of, amongst others, cross-border areas. This article discusses the need and relevance of Cross-Border Impact Assessment to improve evidence-based policymaking, legislative procedure and implementation for (cross-)border regions through a multilevel governance approach. This special variation of the Territorial Impact Assessment may provide an opportunity for studying potential (cross-)border effects emanating from legislation systematically at the European level. |