-

A Introduction

We have been asked to describe how the UK Parliament handles government bills which contain law reform proposals. As the Clerks of Legislation in the UK Parliament’s two Houses, we are responsible to the Clerk of each House for the procedures which allow Members to subject proposed legislation to public scrutiny and which ultimately confer its authority. We are also responsible for the accuracy and integrity of primary legislative text at every stage from introduction to enactment. So we care about the state of the statute book and the effectiveness of the mechanisms for maintaining it in support of the rule of law.

Parliament has two special procedures, one for consolidation bills, the other for other uncontroversial Law Commission bills.1xThe Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission are statutory independent bodies which keep the law of (respectively) England and Wales (one jurisdiction) and Scotland under review and recommend reform where it is needed. By ‘Law Commission bill’ we mean a government bill based on Law Commission recommendations. Both take proceedings out of the Chamber, reducing the cost to government of including the bill in its legislative programme in terms of political effort and parliamentary time (of which more later). Both allow not for less scrutiny but for scrutiny of a different kind. -

B Consolidation

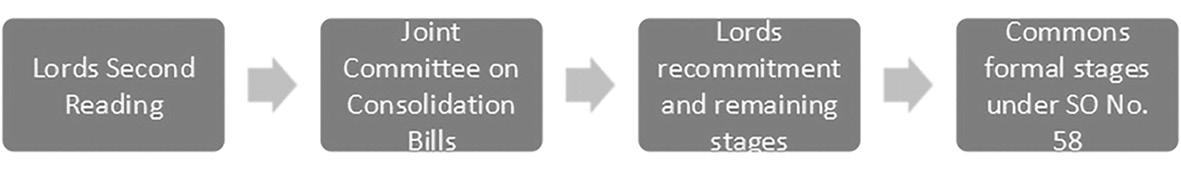

Consolidation bills are tightly defined. In a nutshell, they collect law in multiple Acts and restate it more accessibly but do not change it. They start in the House of Lords. After Second Reading they are examined by the Joint Committee on Consolidation Bills (JCCB) to check that they really do not change the law. They then go through normal House of Lords stages (recommitment to Committee of the Whole House, Report stage and Third Reading) but can be amended only in ways that do not change the law. About 200 were passed in the 40 years following the creation of the Law Commission in 1965.

Progress of a Consolidation Bill

The cost of consolidation to a British government does not arise in Parliament but before that, in government. The Law Commission’s website says, “A worthwhile consolidation does much more than produce an updated text.”2xThe Law Commission and consolidation on www.lawcom.gov.uk/consolidation/ (last accessed 5 May 2020). This is labour-intensive work for expert drafters, whose time is always in demand for other things.

Nonetheless, an updated text is a good start, and the net benefit of consolidation is somewhat diminished by the increasing excellence of legislation.gov.uk, the impressive resource of updated statute law and statutory instruments (delegated legislation made by ministers) provided free by The National Archives, a UK non-ministerial department. 99.5% of primary legislation, and an increasing amount of secondary legislation, is now up to date on legislation.gov.uk, and where it is not, it tells the reader. Its offer is limited to updated text; it does not collate law scattered across the statutory landscape, or case law. But it is free to use and gets any seeker after the law off to a good start.

This may partly explain why there have been only two consolidation bills since 2006.3xThe Charities Bill in 2011 and the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Bill in 2014. Other reasons may include lack of political payoff; political risk that if Parliament gets its hands on an area of law, it will want to change it; and changes to the role of the Lord Chancellor and the relationship between the senior judiciary and Parliament in 2005. The overriding factor is likely to be the impact of austerity on the Civil Service; drafters are in short supply, and a government department requesting consolidation is likely to be told that it will have to pay for it.

The reason for a dwindling of consolidation is certainly not because the statute book is getting simpler; it is not, and the prospective addition to UK law of retained European Union (EU) law from the end of the withdrawal implementation period has made it more complicated. -

C Lords Constitution Committee

In 2017 the House of Lords Constitution Committee reported on preparing legislation for Parliament and came out in favour of consolidation. They reckoned that it pays back in efficiency and accessibility and that not doing it is a false economy.

With parliamentary reports, the evidence is often of as much value as the report itself. The Committee heard from Professor David Ormerod, the Law Commissioner responsible for criminal law, that in one particular area “[o]fficials have been very candid in telling us that they can no longer accurately and confidently predict the impact of further legislative change”.4xHouse of Lords Constitution Committee, The Legislative Process: Preparing Legislation for Parliament – Oral and Written Evidence, published on www.parliament.uk, Q103. That speaks to a risk of not consolidating, that policy changes may have unintended consequences, and to consolidation as a springboard for change. Elizabeth Gardiner CB QC (Hon), First Parliamentary Counsel, who heads the government’s team of expert legal drafters, told the Committee how her team is trying to consolidate ‘as we go’,5xIbid., Q96. by drafting bills to amend previous statutes rather than create new free-standing ones, and by replacing entire extended passages of law rather than making lots of little changes. -

D Keeling Schedules

Legislation by amending previous statutes, rather than by creating a new one to sit alongside others and create a risk of conflict, is referred to as ‘legislation by reference’. Legislating in this way makes for a tidier statute book but is harder for legislators to understand and amend. In 1938 Edward Keeling, MP, proposed that bills to amend another Act should include a Schedule showing the old Act as it would be if the bill passed. The government agreed to try, and Keeling Schedules were born. A Keeling Schedule can be an actual Schedule to the bill. There is a short one in the Criminal Evidence (Amendment) Act 1997. It is explicitly ‘for ease of reference’;6xCriminal Evidence (Amendment) Act 1997 Section 6(2). it is not authoritative. In the House of Commons, if the bill is amended, the Keeling Schedule is amended automatically.7x‘On the direction of the Chair’. Erskine May Parliamentary Practice 25th edition (2019), Para. 28.117. Available at: https://erskinemay.parliament.uk/section/5349/schedules%20and%20new%20schedules/. Or it can be part of the Explanatory Notes; there were examples in 1999 and 2000. Or it can be informal; the responsible government department circulated one for the Disability Discrimination Bill in 2004.

Keeling Schedules are resource intensive to produce, which is perhaps why there are no more recent examples.8xPost-submission note: an informal Keeling Schedule for the Parliamentary Constituencies Bill was published in June 2020. But the Constitution Committee advocated them and reckoned that new technology should make them easier to produce.

-

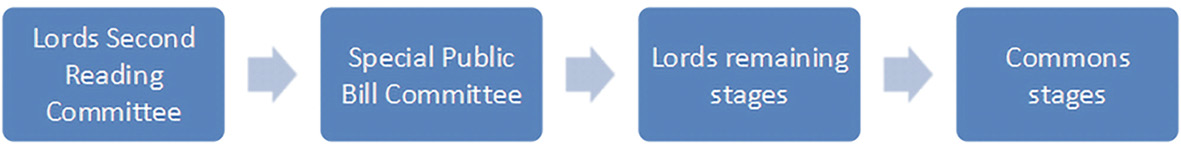

E Law Reform – Uncontroversial

Another special procedure applies to Law Commission bills which do change the law, and so are not consolidation bills, but which are uncontroversial. The decision as to whether a bill is uncontroversial is made in the ‘usual channels’ in the House of Lords – i.e. the opposition and third party leaderships, in discussion with the government behind the scenes. With their agreement, the bill goes to a Second Reading Committee, then to a Special Public Bill Committee. This includes the minister and the other party spokespeople. It starts like a Select Committee, taking oral and written evidence from the government, the Law Commission and anyone else with something to say. It may be expected to pay particular attention to provisions not based on Law Commission recommendations. Then it changes mode and carries out a Committee Stage, considering amendments like a House of Commons Public Bill Committee. Otherwise, the bill goes through normal stages but they are expected to be brisk.

Progress of an uncontroversial Law Commission Bill

This process was born in 2006, during the passage of the Legislative and Regulatory Reform Bill. At that time the backlog of Law Commission reports stood at 14, and all agreed that something needed to be done. The bill included a clause to give the government wide powers to implement Law Commission recommendations by order. That proposal was criticized in the House of Lords, including by two committees which scrutinize all bills: the Constitution Committee and the Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee. These committees act as guardians of the statute book by looking across all bills at, respectively, impacts on the constitution and delegated powers, and both reported against this clause. It would have let ministers amend common law as well as statute law; it would have let them do things not recommended by the Law Commission; and it would have denied Parliament the opportunity to amend. The government conceded, the clause was taken out9xSee House of Lords Official Report 10 July 2006. and this procedure was created instead.

The procedure was set up in 200810xHouse of Lords Procedure Committee, 1st Report 2007-08 agreed by the House on 3 April 2008, and 2nd Report 2010-12 agreed by the House on 7 October 2010. and has been used nine times. Here is a list of the resulting Acts; the bills all started in the House of Lords.Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 2009

Third Parties (Rights Against Insurers) Act 2010

Consumer Insurance (Disclosure and Representations) Act 2012

Partnerships (Prosecution) (Scotland) Act 2013

Trusts (Capital and Income) Act 2013

Inheritance and Trustees’ Powers Act 2014

Insurance Act 2015

Intellectual Property (Unjustified Threats) Act 2017

Sentencing (Pre-consolidation Amendments) Bill – in the Commons at the time of writing11xPost-submission note: the bill received Royal Assent and became law on 8 June 2020.

It will be seen that the procedure delivered roughly one Act a year from 2009 to 2015 but only one since then, with one more on the way. Whether the statute book would be in better shape if the government had received the order-making power which they proposed is one of the imponderables of legal history.

-

F Law Reform – Controversial

Not all Law Commission bills are uncontroversial. One which was not was the Bribery Act 2010, and its scrutiny story is interesting. The Law Commission launched a project on the law of dishonesty in 1994. In 1998 it published a draft Corruption Bill. In 2003 the government published the draft bill for pre-legislative scrutiny by a Joint Committee. The House of Lords was in the lead; the Chair was the late Lord Slynn of Hadley. The Committee was highly critical of, among other things, the definition of ‘corruptly’, which ran to three long clauses. The government consulted further, found no consensus and referred the bill back to the Law Commission.

The Law Commission tried again, narrowing the focus to bribery. Based closely on the Commission’s work, the government published a draft bill in 2009. Again there was pre-legislative scrutiny by a Joint Committee, and again the House of Lords was in the lead; the Chair was the late Viscount Colville of Culross. This time the Committee came down in full support. The bill was introduced in the House of Lords and went through the usual stages. The House of Lords Constitution Committee reported on it twice, focusing on the issue of defences, where the bill differed from the draft bill and what the Law Commission recommended. The government responded with amendments in both Houses. In 2010 the bill became the Act which is held up as a model around the world.

In 2019 a House of Lords Committee carried out post-legislative scrutiny of the Bribery Act. The Committee was chaired by the Rt Hon Lord Saville of Newdigate. It published almost 800 pages of evidence from over 100 witnesses. Its report criticized some aspects of implementation but found the Act itself to be excellent. Neither pre- nor post-legislative scrutiny is systematically applied to Law Commission bills, but this one was subject to both, and we believe they make for better law. -

G Sentencing

The most recent bill to proceed under the special procedure for uncontroversial Law Commission bills was the Sentencing (Pre-consolidation Amendments) Bill [HL]. It was based on a Law Commission project which began in 2014 and reported in 2018. It ran to 5 Clauses and 2 Schedules, amounting to 52 pages of print.

The bill was introduced in the House of Lords in May 2019, as the longest parliamentary session at Westminster since 1649 entered its third year. A Second Reading Committee took place in June, a Special Public Bill Committee sat in July, Report stage took place in September and the bill was carried over the Prorogation which ended the session. Third Reading would have taken place in October but for the General Election. The bill was revived in the new Parliament after the Election and fast-tracked through the Lords and had been given an unopposed Second Reading in the Commons in March 2020, having been debated briefly in a Second Reading Committee, before its further progress was delayed in the wake of 2020’s COVID-19 pandemic.

In the Commons, the minister, Chris Philp, MP, was asked to account for the delay since the Law Commission report in November 2018. He said:In fairness to my predecessors, I should say that 2019 was a rather eventful year in Parliament, with quite a lot going on, including a change of Prime Minister and a general election, along with various other things. As a result, matters progressed through Parliament a little more slowly than they might otherwise have done. The Bill was introduced in May 2019, carried over and then had to be reintroduced after Dissolution. It has suffered from the political turbulence of the past 12 months, but we are here now and want to get it passed as quickly as possible.12xOfficial Report 17 March 2020, col 8.

Pre-consolidation amendments are changes to the law which go beyond consolidation, and so cannot appear in a consolidation bill. They do not introduce significant policy changes but make for better consolidation by tidying up the law, addressing areas that are unclear, and amending inconsistencies and mistakes. And, critically, they take effect immediately before the consolidation itself and only if it goes ahead.

Pre-consolidation amendments are nothing new, but they are normally done as part of a bigger bill or by secondary legislation. A recent example of a delegated power to make such secondary legislation appears as follows in the Charities Act 2006.76 Pre-consolidation amendments

The Minister may by order make such amendments of the enactments relating to charities as in his opinion facilitate, or are otherwise desirable in connection with, the consolidation of the whole or part of those enactments.

An order under this section shall not come into force unless –

a single Act, or

a group of two or more Acts,

is passed consolidating the whole or part of the enactments relating to charities (with or without any other enactments).

If such an Act or group of Acts is passed, the order shall (by virtue of this subsection) come into force immediately before the Act or group of Acts comes into force.

Once an order under this section has come into force, no further order may be made under this section.

This is the first instance of a whole bill being devoted to pre-consolidation. The Insolvency Act 1985 was similar in some respects: it paved the way for a consolidation the following year and came into force only just ahead of the consolidation Act which largely repealed it. But the changes it made to the law were substantial, and it could have stood even if the 1986 Act had failed.

So far we have written only about process, but the substance of this bill also deserves consideration. The aim of the exercise is to consolidate all English and Welsh law on sentencing procedure in a single Sentencing Code. Sentencing is acknowledged to be one of the areas of UK statute law which is most in need of consolidation. The Law Commission says:The current law of sentencing is inefficient and lacks transparency. The law is incredibly complex and difficult to understand even for experienced judges and lawyers. It is spread across a huge number of statutes, and is frequently amended. Worse, amendments are brought into force at different times for different cases. The result of this is that there are multiple versions of the law that could apply to any given case. This makes it difficult, if not impossible at times, for practitioners and the courts to understand what the present law of sentencing procedure actually is.13xLaw Commission. Available at: www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/sentencing-code/ (last accessed 25 April 2020).

As a result, it has been calculated that 1 in 3 appeals from the Crown Court involve an unlawful sentence.14xBased on an analysis of 262 randomly selected cases in the Court of Appeal Criminal Division in 2012. Sentencing Procedure Issues Paper 1 Transition, Law Commission 2015, Para. 1.9. The Code will reduce miscarriages of justice and save £250m over 10 years. Without compromising our political impartiality, we are proud to play a small part in making this happen.

The pre-consolidation bill does two things. It makes pre-consolidation amendments and provides for a ‘clean sweep’. The Code will apply to all convictions after it comes into force; and all offenders convicted after that will be sentenced according to the most up-to-date law, irrespective of when they committed the offence. This works by deeming the most up-to-date law to have come into force before the offence was committed. The minister, the Rt. Hon. Lord Keen of Elie QC, Advocate General for Scotland and House of Lords Spokesperson for the Ministry of Justice, called this ‘a very neatly designed legal tool’15xHouse of Lords Official Report 12 June 2019, col. 15GC. and David Ormerod called it ‘a fiendishly clever drafting device’.16xSpecial Public Bill Committee, Sentencing (Pre-consolidation Amendments) Bill [HL], Oral and written evidence, published on www.parliament.uk, Q7. There are exceptions to ensure that the maximum sentence under the clean sweep is never more than that which applied at the time of the offence.

The bill proceeded through its Lords stages without dissent. Second Reading Committee took an hour and a half. The Special Public Bill Committee sat for another 90 minutes to hear evidence from David Ormerod and the minister. They asked why consolidation was needed, how the bill differed from the Law Commission’s draft, and questions about concerns raised, the coverage of the consolidation and how transition would be managed.

Professor Ormerod told the Committee how much he hoped future changes to sentencing procedure would be done by amending the Code. He said, “I am very optimistic that it will be heavily and frequently amended.”17xIbid., Q8. He even had advice for drafters of new sentencing law in the future, e.g. to keep conviction date as the reference point.

The Committee then sat for another 30 minutes to agree 24 government amendments. It published 20 pages of written evidence. Report stage was formal.

The bill fell when Parliament was dissolved for the Election but reappeared in the first Queen’s Speech of the new Parliament in December. It was reintroduced with some changes, mainly to keep up with continuing work on the Sentencing Code itself. In January 2020 it received a fresh Second Reading; further House of Lords stages were formal. When the Bill arrived in the Commons, it was in the usual way given its formal First Reading by ‘book entry’ (logged in the minute book by the Clerks at the Table and recorded in the daily Votes and Proceedings) and, by virtue of Standing Order No. 59, stood referred to a Second Reading Committee.

Meanwhile, in March 2020, the government introduced the Sentencing Bill [HL]. This was the consolidation bill itself, for which the pre-consolidation amendments paved the way. It was very substantial, running to 420 Clauses and 29 Schedules, 569 pages of print. As usual, the Explanatory Notes which the government produces for non-consolidation bills were absent, since the bill involved no change of law, policy or expenditure requiring explanation. Instead, as usual, it was accompanied by a Table of Origins showing where in the statute book each provision of the consolidation bill could be traced back to. For the JCCB the drafters also produced a Table of Destinations, showing where each provision in the legislation being consolidated could be found in the new bill, and extensive notes.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, it was expected that the major bill would receive its Second Reading and be referred to the JCCB as soon as the minor pre-consolidation bill had completed its Commons stages.18xPost-submission note: Second Reading of the major bill took place on 25 June 2020. The timing of those latter Commons stages of the minor bill was in turn predicated on the Northern Ireland Assembly from whom a legislative consent motion would be expected before the bill was given its Commons Third Reading – its presumably final stage, as no amendments were expected to be made in the Commons. While not an absolute statutory bar on the bill’s further progress, the Sewel convention (as recognized, for example, in Section 28(8) of the Scotland Act 1998 and in Section 107(6) of the Government of Wales Act 2006) that the Westminster Parliament will not normally legislate with regard to devolved matters without the consent of the devolved legislatures (the Scottish Parliament, the Northern Ireland Assembly and – in Wales – Senedd Cymru) is generally observed. The Scottish Parliament passed such a motion on 31 October 2019.

The pre-consolidation bill took no more than a brisk 20 minutes of debate in Second Reading Committee, with the House of Commons giving the bill an unopposed Second Reading the following day. The bill was by default committed to a public bill committee, although it remained open to the government to discharge the bill from the public bill committee and commit it instead to a Committee of the whole House, in the expectation of completing all its remaining Commons stages at a single sitting.

There the matter rests at the time of writing. The government is expected to move these bills forward as soon as possible, to facilitate further substantive legislation affecting sentencing. Readers wishing to know the latest position should look up the bill on www.parliament.uk. -

H Parliamentary Scrutiny of the Government’s Law Reform Programme

The Law Commission Act 2009 amended the Law Commissions Act 1965 to place a duty on the Lord Chancellor to lay before Parliament an annual report on Law Commission proposals implemented and proposals that have not been implemented, including plans for dealing with any of those proposals and any decision not to implement any of those proposals.

The precise statutory requirement is to publish these implementation reports as soon as practicable after the end of each year, starting with the day on which the statutory duty created by Section 1 of the Law Commission Act 2009 came into force, which was 12 January 2010.Reporting year Dates of publication HC Act Paper or Command number To 11 January 2011 24 January 2011 HC 719 To 11 January 2012 22 March 2012 HC 1900 To 11 January 2013 22 January 2013 HC 908 To 11 January 2014 8 May 2014 HC 1237 To 11 January 2015 12 March 2015 HC 1062 To 11 January 2016 12 January 2017 HC 613 To 11 January 2017 – – To 12 January 2018 30 July 2018. Covers period from 12 January 2017 to 30 July 2018; published as a Command Paper because laid before Parliament during the summer adjournment Cm 9652 To 12 January 2019 Still not published at time of writing To 12 January 2020 Still not published at time of writing As the table shows, latterly the Ministry of Justice (under seven Lord Chancellors in less than 10 years) has become rather approximate in fulfilling its statutory duty to make annual reports keeping Parliament and the wider public apprised of the state of play over implementing Law Commission recommendations.

Similarly, Section 3C of the Law Commissions Act 1965, as inserted by Section 25 of the Wales Act 2014, places a duty on the Welsh ministers to report to the National Assembly for Wales (now Senedd Cymru) each year on the extent to which Law Commission proposals have been implemented by the Welsh Government. Such annual reports, covering the years from 17 February 2015, have been made promptly: on 16 February 2016, 16 February 2017, 16 February 2018, 15 February 2019 and 14 February 2020.I Government Priority and Parliamentary Time

The other main provision of the 2009 Act was to provide for the Lord Chancellor and the Law Commission to agree a protocol about the principles and methods to be applied in deciding the work to be carried out by the Law Commission and in the carrying out of that work, the assistance and information that Ministers of the Crown and the Law Commission are to give each other, and the way in which Ministers of the Crown are to deal with the Law Commission’s proposals for reform, consolidation or statute law revision. The Protocol was duly signed in March 2010.19xProtocol between the Lord Chancellor (on behalf of the Government) and the Law Commission, Law Com No 321, published as HC 499 and available on the Law Commission website. It included provision for departments to give an undertaking that there is a serious intention in the department to take forward law reform in an area where ministers requested work from the Law Commission and to make funding proposals for such projects.

One might have expected that, if the Protocol worked well, there would be an increase in the success rate of Law Commission recommendations. A full analysis of the impact of the Protocol and its implied funding model is beyond the scope of this article but, as remarked upon above, there has been a falling off in the number and frequency of consolidation and stand-alone Law Commission bills reaching Parliament in recent years.

In the annual reports on the implementation of Law Commission recommendations, reference is sometimes made to parliamentary time, with the government promising to bring forward legislation ‘when parliamentary time allows’.

Parliamentary time, in its literal sense, is abundant. According to the sessional diaries compiled and published online by the House of Commons Journal Office, the amount of time devoted to government bills in the last few normal-length sessions ranged from 194 hours in 2014-2015 to 337 hours in 2013-2014. In the sessions since the new procedure for Law Commission bills was introduced, there has never been more than one Law Commission bill in a session. The amount of (literal) time taken on the floor of the House by Law Commission bills has been tiny: around 0.05% of the total time spent in any session on the floor of the House.Session Total sitting hours House of Commons Chamber (hh:mm) Of which: Govt bills (hh:mm) Govt bills as % of total hours Law Cssion bills hours in HC Chamber (hh:mm) Law Cssion bills as % time spent on Govt Bills in HC Chamber Law Cssion bills as % total hours in HC Chamber 2019 (short) 113:34 9:16 8.2 nil 0 0 2017-2019 (long) 2869:35 534:24 18.6 nil 0 0 2016-2017 (short) 1065:37 235:42 22.1 00:36 0.06 0.25 2015-2016 1215:03 289:46 23.8 nil 0 0 2014-2015 989:25 193:54 19.6 00:29 0.05 0.25 2013-2014 1273:24 337:27 26.5 00:40 0.05 0.20 2012-2013 1133:18 286:17 25.3 00:33 0.04 0.19 2010-2012 (long) 2344:19 652:14 27.8 01:25 0.06 0.22 2009-2010 (short) 540:12 156:00 28.9 00:12 0.04 0.13 2008-2009 1053:51 257:50 24.5 00:22 0.04 0.14 Source: House of Commons Sessional Diaries, www.parliament.uk (forthcoming, for 2017-2019 and 2019 Sessions)

A study conducted by Philippa Hopkins (now QC) as a research assistant at the Law Commission in the summer of 1994 was published as Parliamentary Procedures and the Law Commission – A Research Study.20xLaw Commission, November 1994. Ms Hopkins found that Law Commission bills did not (italics in original) take up large amounts of time on the floor of either House, even then. The average time taken up by minor bills incorporating Law Commission reform proposals from 1984-1985 to 1992-1993 in the Lords was 1 hour and 49 minutes and in the Commons was 1 hour and 11 minutes.

A more recent survey of time spent in the Commons, including the length of debates in the Second Reading Committee and in public bill committees, echoes her conclusion, with an average of 1 hour and 21 minutes spent on each Law Commission bill brought to the Commons between 2008-2009 and 2019, of which an average of 32 minutes was taken on the floor of the House. For these eight bills, the median interval from a bill arriving in the Commons to receiving Royal Assent was between 25 and 28 sitting days.Session Second Reading Committee (hh:mm) PBC/CWH (hh:mm) Report/Third Reading (hh:mm) Total (hh:mm) Sitting days from 1R to RA 2016-2017 Intellectual Property (Unjustified Threats) Act 2017 00:18 00:47 00:36 01:41 62 2014-2015 Insurance Act 2015 00:25 00:24 (CWH) 00:05 00:54 17 2013-2014 Inheritance and Trustees’ Powers Act 2014 00:46 00:15 00:40 01:41 42 2012-2013 Partnerships (Prosecution) (Scotland) Act 2013 00:40 00:57 00:32 2:09 25 2012-2013 Trusts (Capital and Income) Act 2013 00:20 00:04 00:01 00:25 54 2010-2012 Consumer Insurance (Disclosure and Representation) Act 2012 00:29 00:30 01:25 02:24 29 2009-2010 Third Parties (Rights Against Insurers) Act 2010 00:29 00:1 00:12 00:42 18 2008-2009 Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 2009 00:29 00:00 00:22 00:51 15 In the Commons, at any rate, the government determines the legislative agenda. Government business takes precedence at every sitting except in the case of private bills (which are very few and far between these days), private Members’ (that is, non-ministerial) bills and debates on days allocated to opposition or backbench (another way of saying non-ministerial) business.

The government’s legislative priorities, as laid out in the Queen’s Speech programme outlined at the beginning of each (normally annual) session, are determined by the Cabinet’s Parliamentary Business and Legislation (PBL) Committee, chaired by the Leader of the House of Commons. PBL adds to or occasionally subtracts from the programme over the course of a session to reflect the government’s changing priorities as it responds to events.

It appears that free-standing Law Commission bills struggle to get picked from among competing proposals brought to PBL, especially when other bills have greater topicality or immediate political salience.

If Law Commission recommendations contribute to or complement the government’s current intentions, they might be incorporated into flagship bills. For example, a revised electronic communications code was briefly inserted into the Infrastructure Bill of 2014-2015, before being removed for further consultation and then resurfacing in the Digital Economy Bill of Session 2016-2017.

But the conventional excuse of lack of parliamentary time deflects blame for a lack of progress in implementing Law Commission proposals away from a lack of prioritization within government and towards implied deficiencies in the parliamentary process. -

J Conclusion: What More Can Parliament Do?

We have described how the UK Parliament scrutinizes consolidation and law reform bills, considered the adequacy of parliamentary scrutiny of the government’s law reform programme and tested the proposition that law reform is impeded by a shortage of parliamentary time. We conclude with a brief survey of some ways in which Parliament could encourage and facilitate these important forms of legislation.

First, Parliament has rules governing the scope of a bill and the relevance of amendments which Members may propose. For a consolidation bill, the rule is tight:Where the title of a bill is only to consolidate the law on a particular subject, it is out of order to amend the provisions of the statutes which by the bill are to be consolidated and fused together, as any such amendments are regarded as outside the scope of the bill, and were not contemplated when the House gave it a second reading.21xErskine May (2019), Para. 28.110.

For any other bill, the rules are less restrictive. “The scope of a bill represents the reasonable limits of its collective purposes, as defined by its existing clauses and schedules.”22xIbid., Para. 28.81. Broadly speaking, Members may propose amendments to change the policy of a bill, to do things which ministers could do under powers proposed to be delegated or to do other things in the same policy area.

It has been suggested that Parliament’s rules of scope and relevance deter ministers from ‘consolidating as we go’ by exposing any provision included in a non-consolidation bill to substantive amendments. It is possible to imagine a different relevance rule for elements of a bill which involve no change to law, policy, taxation or expenditure but that are included only for consolidation. This would bar substantive amendments, of the kind that would be barred in the case of a consolidation bill. It would need to be clear which parts of the bill were protected in this way; this might be achieved by creating an authoritative version of a Keeling Schedule (see above). The Welsh Government recently proposed this approach for amendments to secondary legislation.23x“One option under consideration is that instead of changing the law by amending a statutory instrument using another statutory instrument (thus creating two, and then more each time amendments are made), the change is achieved by remaking the original statutory instrument in its entirety but with amendments made to it. Although, this would require a change to the procedures in standing orders, only the amendments to the statutory instrument should be subject to scrutiny.” The Future of Welsh Law: Classification, Consolidation, Codification, Welsh Government Consultation Document October 2019, Para. 93.

Such a change would need to be well defined and even then might not commend itself to Parliament. Parliament exists to scrutinize legislation, not merely to applaud as it goes by, and parliamentarians should not be prevented from seizing such legislative opportunities as any government may choose to present.

Nor is it likely that a fresh attempt to give the government power to implement Law Commission recommendations by order would be any more successful than it was in 2006.

It might be possible for Parliament to take (or to be given) more ownership of the programme of law reform. If this were so, the two Houses might be more amenable to restrictive scope rules. The JCCB is at present an entirely reactive body, meeting only to consider such bills as the government brings forward. The remit of the JCCB could be extended to include reporting on situations when consolidation of the statute book appears to be urgently needed but is making insufficient progress. There are select committees in both Houses which could, within their existing terms of reference, take a similarly proactive role in relation to wider law reform.

It may be that there are other tools already available which government and Parliament could be using. The Consolidation of Enactments (Procedure) Act 1949 created a procedure for ‘corrections and minor improvements’ which “do not effect any changes in the existing law of such importance that they ought […] to be separately enacted by Parliament”.24xConsolidation of Enactments (Procedure) Act 1949 Section 1. It has not been used since the 1960s.Procedure under Consolidation of Enactments (Procedure) Act 1949

The Lord Chancellor publishes a memorandum and invites representations

The Lord Chancellor lays the memorandum before Parliament

The Lord Chancellor introduces a Bill to consolidate with corrections etc

The Bill, the memorandum and any representations are referred to the JCCB

The JCCB considers these – at least 1 month after laying

The JCCB informs the Speakers of the two Houses what corrections, etc they approve

The Speakers say whether they concur

The JCCB amends the bill and reports

The corrections, etc cannot be amended, and no new corrections, etc can be proposed

And in 1981 the JCCB agreed a procedure for amendments which change the law but “no more than is necessary to produce a satisfactory consolidation”. Proposed amendments of this kind are to be examined by the committee together with Law Commission recommendations, but the committee, instead of being asked to make the amendments, is invited to report to both Houses that the amendments change the law no more than is necessary to achieve a satisfactory consolidation. The amendments, supported by such a report, would then be moved on the floor of the House of Lords on recommitment. This procedure has never been used but is recorded in a footnote in Erskine May.25xErskine May (2019), Para. 41.9, fn 9.

Legislation has traditionally been created and used as text, but there is growing interest in treating it as data and even as ‘code’ in the information technology sense. A project is in hand to develop new bill drafting software, for use by Parliamentary Counsel, parliamentary officials and The National Archives.26xThe Legislative Drafting, Amending and Publishing Programme (LDAPP). The project aims to deliver user-friendly tools for managing legislative text in high-quality structured XML at all stages of the legislative life cycle and a standards-compliant platform enabling further digital improvements. Among other benefits, this should make it easier to produce Keeling Schedules.

Finally, the Welsh Government recently consulted on a proposal that Standing Orders of Senedd Cymru (formerly the National Assembly for Wales) should protect a consolidated Act like the Sentencing Code so that any future attempt to legislate outside it would have to be justified.27xWelsh Government Consultation Document October 2019, Para. 91. It is possible to imagine a Westminster version of this procedure.

We would welcome further proposals from readers of this article. - * Based on papers delivered at the 5th annual workshop of the Law Reform Project of the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, ‘Parliamentary scrutiny of law reform: procedures, bodies and methods’, in November 2019.

-

1 The Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission are statutory independent bodies which keep the law of (respectively) England and Wales (one jurisdiction) and Scotland under review and recommend reform where it is needed. By ‘Law Commission bill’ we mean a government bill based on Law Commission recommendations.

-

2 The Law Commission and consolidation on www.lawcom.gov.uk/consolidation/ (last accessed 5 May 2020).

-

3 The Charities Bill in 2011 and the Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Bill in 2014.

-

4 House of Lords Constitution Committee, The Legislative Process: Preparing Legislation for Parliament – Oral and Written Evidence, published on www.parliament.uk, Q103.

-

5 Ibid., Q96.

-

6 Criminal Evidence (Amendment) Act 1997 Section 6(2).

-

7 ‘On the direction of the Chair’. Erskine May Parliamentary Practice 25th edition (2019), Para. 28.117. Available at: https://erskinemay.parliament.uk/section/5349/schedules%20and%20new%20schedules/.

-

8 Post-submission note: an informal Keeling Schedule for the Parliamentary Constituencies Bill was published in June 2020.

-

9 See House of Lords Official Report 10 July 2006.

-

10 House of Lords Procedure Committee, 1st Report 2007-08 agreed by the House on 3 April 2008, and 2nd Report 2010-12 agreed by the House on 7 October 2010.

-

11 Post-submission note: the bill received Royal Assent and became law on 8 June 2020.

-

12 Official Report 17 March 2020, col 8.

-

13 Law Commission. Available at: www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/sentencing-code/ (last accessed 25 April 2020).

-

14 Based on an analysis of 262 randomly selected cases in the Court of Appeal Criminal Division in 2012. Sentencing Procedure Issues Paper 1 Transition, Law Commission 2015, Para. 1.9.

-

15 House of Lords Official Report 12 June 2019, col. 15GC.

-

16 Special Public Bill Committee, Sentencing (Pre-consolidation Amendments) Bill [HL], Oral and written evidence, published on www.parliament.uk, Q7.

-

17 Ibid., Q8.

-

18 Post-submission note: Second Reading of the major bill took place on 25 June 2020.

-

19 Protocol between the Lord Chancellor (on behalf of the Government) and the Law Commission, Law Com No 321, published as HC 499 and available on the Law Commission website.

-

20 Law Commission, November 1994.

-

21 Erskine May (2019), Para. 28.110.

-

22 Ibid., Para. 28.81.

-

23 “One option under consideration is that instead of changing the law by amending a statutory instrument using another statutory instrument (thus creating two, and then more each time amendments are made), the change is achieved by remaking the original statutory instrument in its entirety but with amendments made to it. Although, this would require a change to the procedures in standing orders, only the amendments to the statutory instrument should be subject to scrutiny.” The Future of Welsh Law: Classification, Consolidation, Codification, Welsh Government Consultation Document October 2019, Para. 93.

-

24 Consolidation of Enactments (Procedure) Act 1949 Section 1.

-

25 Erskine May (2019), Para. 41.9, fn 9.

-

26 The Legislative Drafting, Amending and Publishing Programme (LDAPP).

-

27 Welsh Government Consultation Document October 2019, Para. 91.

DOI: 10.5553/EJLR/138723702020022002006

European Journal of Law Reform |

|

| Article | Law Reform Bills in the Parliament of the United Kingdom |

| Keywords | law reform, consolidation, statute law, parliament, Law Commission |

| Authors | Andrew Makower en Liam Laurence Smyth * xBased on papers delivered at the 5th annual workshop of the Law Reform Project of the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, ‘Parliamentary scrutiny of law reform: procedures, bodies and methods’, in November 2019. |

| DOI | 10.5553/EJLR/138723702020022002006 |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Abstract Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

Suggested citation

Andrew Makower and Liam Laurence Smyth, 'Law Reform Bills in the Parliament of the United Kingdom', (2020) European Journal of Law Reform 164-179

Andrew Makower and Liam Laurence Smyth, 'Law Reform Bills in the Parliament of the United Kingdom', (2020) European Journal of Law Reform 164-179

|

The officials responsible for the procedures for scrutiny of proposed legislation in the UK Parliament and for the accuracy and integrity of legislative text describe how the UK Parliament scrutinizes consolidation and law reform bills and the government’s law reform programme, test the proposition that law reform is impeded by a shortage of parliamentary time, and survey ways in which Parliament could encourage and facilitate such legislation. |