-

A Introduction

In June 2013, the European Commission introduced the reform on antitrust damages actions (hereinafter ‘EU private antitrust reform’). The most gratifying thing about the reform is that the European Union eventually adopted the Directive on damages actions in November 2014.1x Directive 2014/104/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 November 2014 on certain rules governing actions for damages under national law for infringements of the competition law provisions of the Member States and of the European Union [2014] OJ L349 (Directive hereinafter). Therefore, the EU member states had been required to implement the provisions of the Directive in their national laws by the end of 2016. In reality, however, the states have struggled in implementing this Directive: only five countries had adopted the legislation in time.2x See Commission, ‘Competition’, available at: <http://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/actionsdamages/directive_en.html> accessed 28 December 2016. But the most disappointing attribute of the reform is that the Directive includes no provisions on collective litigation. Instead, the Commission adopted the non-binding Recommendation on collective redress.3x Commission Recommendation of 11 June 2013 on common principles for collective redress mechanisms in the Member States for injunctions against and claims on damages caused by violations of EU rights COM(2013) 3539/3 (Recommendation hereinafter). Although the Recommendation takes the form of a horizontal framework, the importance for antitrust litigation is particularly emphasized by the fact that it was adopted together with the proposal for a Damages Directive (2013).

The major goal of the Directive is that any victim who has suffered harm caused by antitrust infringement should effectively exercise the right to claim full compensation.4x Directive, supra note 1, Art. 3. This objective is very ambitious, as it requires to enable each financial victim (direct and indirect purchasers) to obtain full compensation (actual loss plus expectation loss). By emphasizing full compensation, the EU extends this principle both to private and collective actions.

This policy is contrary to the approach in the United States, where private antitrust enforcement and especially small-value class actions primarily serve the objective of deterrence. Although the US legal system significantly differs in terms of rationale, the EU is modelling collective actions with the aim to prevent the perceived litigation abuses of US class actions. It is believed that conservative tools (such as the opt-in measure and the absence of private funding possibilities) would achieve the objective of full compensation. However, when realizing the compensation-based mechanism, it will be shown that measures of deterrence are vital for ensuring the enforcement of full compensation. In light of these provisions, this article will explore three ambitious scenarios of collective redress that include different type of deterrence-based remedies. The principal aim is to assess their abilities to achieve the objective of compensation, and the potential effect on deterrence. The discussion on more forceful collective redress schemes is important for the expected amendment in the field of collective redress. The European Commission will assess the Recommendation’s implementation and, if appropriate, propose further measures by 26 July 2017. Therefore, it is the right time to take a closer look at the scenario of collective redress that would best facilitate the compensation objective, but would not cross the limits of the enforcement of full compensation.

Following this introduction, Section B briefly discusses the main reasons of the determined failure of the compensation goal in antitrust collective litigation. Section C presents three assertive scenarios that cross the limits of the EU proposal. It further discusses the justification of each of them and their impact on compensation and deterrence. Section D aims to design the best possible compensation mechanism that is within the borders of the enforcement of full compensation, as well as being within legal traditions (at least in some member states). This section ends with a discussion on how this mechanism interacts with full compensation. Section E discusses the potential legislative measure of the EU approach on collective redress. The results are summarized in Section F. -

B The Predetermined Failure of the Compensation Goal

By shaping the policy preferences in private actions, the Directive on damages actions established the principle of full compensation. It means that victims shall have the right to compensation for actual loss and for loss of profit, plus the payment of interest. In fact, the perception of full compensation obliges to compensate any natural or legal person down the supply chain (including the end consumer) who has suffered harm caused by an infringement of competition law. It means that both direct and indirect purchasers are entitled to full compensation. The Recommendation, however, has no particular aim to ensure the effective exercise of the victim’s right to full compensation. Rather, it seeks to facilitate access to justice, stop illegal practices, and enable victims to obtain compensation in mass harm situations.5x Recommendation, supra note 3, para. 1. But it seems clear that the principle of full compensation would be applicable in antitrust collective actions, because all victims are entitled to exercise the right to claim full compensation. Despite the grand compensation goal, the compensatory effectiveness is significantly diminished by three important aspects.

First, the Directive orders the robust protection of public enforcement. It contains a complete protection from disclosure of leniency statements and settlement submissions, i.e., the directly incriminating evidence.6x Directive, supra note 1, Art. 6. Such a protection reduces the incentives to bring follow-on damages actions. An even more disappointing fact is that stand-alone actions are not enhanced at all. The Directive only introduces a court-ordered scheme that requires national courts to order the disclosure only when the claimant presents a reasoned justification.7x Ibid., Art. 5. This is in contrast with the liberal party-initiated discovery mechanism in the United States.8x Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 26.

Second, the Directive fails to keep a balance between the claims of direct and indirect purchasers. In fact, the special treatment of indirect purchasers is a welcome step. However, the availability for the defendants to invoke the passing-on defence against a damages claim creates many uncertainties and complexities for direct purchasers. If the defendant proves that the overcharge was passed down the distribution chain, the direct purchasers suffer the decreased damages award, which equals the amount that has been passed on.9x S. Peyer, ‘Compensation and the Damages Directive’, CCP Working Paper 15-10, 2015, p. 25, available at: <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Papers.cfm?abstract_id=2654187> accessed 10 January 2017. Yet, it is highly unlikely that the downstream harm would ever be litigated; the further down victims are found down the supply chain, the less interest to litigate they have. In addition, the passing-on defence causes crucial difficulties for quantifying the exact amount passed down the distribution chain.

Third, even though the Directive facilitates indirect purchasers’ claims, the new opportunity is considerably restricted if collective redress schemes were designed following the proposed principles of the Recommendation. Regardless of whether the claims are brought by direct or indirect purchasers, it is unclear who will have the financial means and capacity to organize and lead the group under an opt-in basis. This is especially true in end consumer actions where victims have the least motivation to go to court, because they normally suffer a spread harm of low value.10x J. Drexl, ‘Consumer Actions after the Adoption of the EU Directive on Damage Claims for Competition Law Infringements’, Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition Research Paper No. 15-10, 2015, p. 2, available at: <http://ssrn.com/abstract=2689521> accessed 13 January 2017. In such circumstances, it is important to inform victims (such as, consumers) about the proposed litigation and hence to convince them to join the action. However, this information campaign may require significant costs while only few victims may adhere to the action; after all, consumers are typically apathetic towards litigation if only a small award is expected. Furthermore, consumers cannot easily opt for an action, because they are unaware that they are being, or have been, harmed by antitrust infringements, or they cannot prove their legal interest (for example, the consumer did not save the proof of the purchase). Therefore, organizing the group may be too risky considering the low expected compensation. The problems in collecting victims for opt-in collective actions are well illustrated through the examples in France (Mobile cartel case)11x The follow-on collective action was brought on the basis of the Decision of 30 November 2005, Counseil de la Concurrence (Competition Council), No. 05-D-65. The claim was brought by the French consumer organization (UFC-Que Choisir). and the UK (Replica Football Shirts).12x In the UK, the consumer association Which? brought a collective damages claim as a consequence of a cartel violation that fixed the price of football kits. A collective claim was based on the following decisions: OFT decision of 1 August 2003 No. CA98/06/2003; Allsports Limited, JJB Sports plc v. Office of Fair Trading [2004] CAT 17; Umbro Holdings Ltd, Manchester United plc, Allsports Limited, JJB Sports plc v. Office of Fair Trading [2005] CAT 22; and JJB Sports plc v. Office of Fair Trading [2006] Court of Appeal, EWCA Civ 1318. In spite of broad media campaigns in both states, only a few hundred of victims joined the actions, while the infringements had potentially caused harm to millions of consumers.13x Out of 20 million victims, only 12,350 consumers joined the actions. Out of 2 million victims, only 130 consumers participated in the action. These examples have become a source of concern for an opt-in measure not being the right solution for the antitrust collective litigation. This is probably one of the main reasons for opt-in collective antitrust actions having been extremely unpopular in the EU member states afterwards. -

C The Fulfilment of the Compensation Goal under More Assertive Scenarios of Collective Redress

The EU’s desire to ensure access to justice and full compensation to antitrust victims collides with another desire that is to prevent abusive litigation.14x See Recommendation, supra note 3, para. 1; Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, ‘Towards a European Horizontal Framework for Collective Redress’ COM (2013) 401/2. According to the European Commission, this phenomenon can be found in the American system, which contains the ‘toxic cocktail’: contingency fees, punitive damages, opt-out schemes, and wide-ranging discovery.15x See, e.g., Commission, ‘Green Paper on Consumer Collective Redress – Questions and Answers’, MEMO/08/741, 2008, para. 9, available at: <http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-08-741_en.htm> (last accessed 19 January 2017). It should be added that the ‘loser pays’ principle – the most widely adopted allocation method for legal costs in the EU member states – has been rejected in the American system. Instead, the US introduced a plaintiff-friendly one-way-fee shifting rule.16x Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 15(a). These measures are aimed at enhancing the objective of deterrence through private attorneys (the so-called ‘private attorney general’). The combination of these measures ensures the viability of antitrust collective litigation. First of all, attorneys are allowed to act as private litigators through contingency fees, which allow for the lawyer to receive a percentage of the recovery. When this compensation model is combined with treble damages and an opt-out measure, private attorneys are given the chance to reap significant awards.17x For example, if an aggregate damage after trebling is $100 million and the contingency fees are 20%, the attorney can foresee a compensation of $20 million. Even if the case is settled, the possibility of receiving a compensation in the millions remains realistic. While it may already seem a good mix, the American deterrence-built mechanism is further reinforced by the liberal party-initiated disclosure scheme and the one-way fee-shifting rule. Despite that, the American private antitrust system does not (completely) achieve its intended goals. First, a large majority of cartels remain undetected.18x Even under to the most optimistic scenario, it is estimated that only up to 33% of cartel violations are detected. See, e.g., J.M. Connor & R.H. Lande, ‘Cartels as Rational Business Strategy: Crime Pays’, Cardozo Law Review, Vol. 34, 2012, p. 427, at 486-490. Second, a large number of private actions, and more specifically class actions, fail: a rather small number of victims receive only very small compensation proportionally.19x See, e.g. B.T. Fitzpatrick & R.C. Gilbert, ‘An Empirical Look at Compensation in Consumer Class Actions’, Vanderbilt Public Law Research Paper No. 15-3, 2015, available at: <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2577775> (last accessed 9 February 2017); Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, ‘Arbitration Study: Report to Congress Pursuant to Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act § 1028(A)’, 2015, available at: <http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201503_cfpb_arbitration-study-report-to-congress-2015.pdf> (last accessed 19 January 2017); Mayer Brown LLP, ‘Do Class Actions Benefit Class Members? An Empirical Analysis of Class Actions’, 2013, available at: <https://www.mayerbrown.com/files/uploads/Documents/PDFs/2013/December/DoClassActionsBenefitClassMembers.pdf> (last accessed 19 January 2017); N.M. Pace & W.B. Rubenstein, ‘How Transparent Are Class Action Outcomes? Empirical Research on the Availability of Class Action Claims Data’, RAND Institute for Civil Justice Working Paper, 2008 <billrubenstein.com/Downloads/RAND%20Working%20Paper.pdf> (last accessed 19 January 2017). Another issue is that the private attorney general mechanism may create possibilities of abuse of litigation by way of pressuring the defendants to settle cases lacking merit.

However, there is no evidence that the introduction of one or two American elements of deterrence (not the entire combination) would inherently attract frivolous litigation in the EU context. The American mechanism is composed of five interrelated elements: the absence of one may significantly reduce the possibilities to abuse the litigation. First, a liberal party-initiated discovery means that the claimant is entitled to request a broad range of the discovery material, which typically causes extremely high costs for the defendant. In contrast, the plaintiffs (a class) have a relatively small number of responsive materials.20x See, e.g., Boeynaems v. LA Fitness International, LLC 285 F.R.D. 331, 334-335, 341 (E.D. Pa. 2012). Second, the one-way fee shifting means that defendants have no right to obtain attorney’s fees, while the plaintiff is entitled to not only treble damages, but also to attorney’s fees as part of his costs of claim.21x Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 15(a). Third, it is obvious that punitive damages or opt-out schemes are indispensable elements for blackmailing defendants, as both generate substantial financial value of claims. Fourth, the availability of contingency fees exacerbates the blackmail as well. Attorneys are incentivized to settle, because their compensation is determined to be large (due to the large number of victims in the class). Last but not the least is the fact that private antitrust actions should be ended in jury trials. It is obvious that final decisions are always unpredictable. Indeed, ordinary citizens, even before the trial, may have a predetermined negative view about a large corporation that potentially caused harm to consumers. When these measures are combined, they raise many incentives for the defendant to settle even unmeritorious claims rather than go to trial with unpredictable jury trials: a loss may cause significant and potentially irreparable damage, both reputational and financial.

Given that the EU’s compensation objective fails to a large extent, this article will explore forceful scenarios and assess their effectiveness for facilitating the objective of compensation, and what is a side effect on deterrence. These scenarios are shown in Table 1.Table 1 The potential scenarios of antitrust collective litigationExceptional measure Permanent measure Scenario 1 Multiple damages and opt-in scheme Contingency fees (third party funding as an additional remedy) Scenario 2 Wide-ranging discovery (only in indirect purchasers’ claims) and opt-in scheme Contingency fees (third party funding as an additional remedy) Scenario 3 Opt-out scheme Contingency fees (third party funding as an additional remedy) At the outset, some important clarifications should be made. Each scenario combines two deterrence-based measures. This approach has been chosen because it gives a better perspective for assessing the impact of separate measures on compensation. One measure alone, regardless of what it is, may have little influence on compensation, but when combined with other measures, it may bring a lot of positive effect. The combination of three measures may hinder the assessment of separate measures, as what effect each measure brings on compensation will be unknown. With regard to each scenario individually, the following clarifications should be made. In Scenario 1, the proposal of multiple damages is within the limits of the enforcement of full compensation. In opt-in actions, multiple damages are necessary to recompense high organization costs and to ensure full compensation standards (actual loss plus expected loss). To the same extent, the proposed wide discovery rules in Scenario 2 are vital for the enforcement of full compensation in indirect purchaser cases. The objective of full compensation requires the “courts [to] chase the harm downstream to the ultimately injured party.”22x D.A. Crane, ‘Optimizing Private Antitrust Enforcement’, Vanderbilt Law Review, Vol. 63, 2010, p. 673, at 701. Further down the distribution chain, plaintiffs have less evidence to prove the harm suffered. Therefore, only ensured access to directly incriminating evidence could facilitate the chances of proving damages in follow-on cartel actions. Finally, an opt-out measure proposed in Scenario 3 is in accordance with the group formation model in some EU member states. So far, these actions have not attracted abusive litigation.

From Table 1, it can be seen that contingency fees and third party litigation are proposed in all scenarios. It is of crucial importance to include private litigators in collective redress schemes, since public standing cannot be considered a tool for facilitating the objective of compensation. In most EU member states public authorities (e.g., consumer organizations) do not have sufficient financial capacity, human resources or legal expertise to represent the multitude of victims in antitrust collective actions.23x B. Kutin, ‘Consumer Movement in Central and Eastern Europe’, Consumatori, Dirittei Mercato, Vol. 2, 2011, p. 106, available at: <www.consumatoridirittimercato.it/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/2011-02-consumer-movement-in-central-and-eastern-europe-n543470.pdf> (last accessed 27 January 2017). According the author, consumer organisations in Central and Eastern Europe are understaffed and have a small number of paid employers. Only a few entities have more than 10 employees. The budget is usually around 300,000 euro or less. Some consumer entities rely on volunteers. In a few other countries consumer organizations are financially strong (for example, in Germany, France and in the UK), but they may keep from taking such antitrust collective actions that are not predetermined to succeed. The loss might significantly diminish the reputation of consumer organizations, knowing they had represented the group of consumers. To the same extent, the public authority can be restrained to bring the claim on behalf of certain group of victims if their loss is not directly related to the activities of that entity. On the other hand, attorneys have the ability to represent numerous victims in all types of legal matters. Moreover, private firms are much more experienced in litigation and thus they can even find ways to deal with cases that might be seen unattractive for public authorities. From a quantitative perspective, there are a large number of attorneys who may seek representation in collective antitrust litigation. But in order to attract lawyers to engage in group litigation, they should be allowed to obtain awards that outweigh the risks. One of the best options is to allow for attorneys to sign a contingency fee agreement with clients, yet this reimbursement model has to be reinforced by other tools. As the examples in Lithuania and Poland have shown, the introduction of contingency fees alone cannot increase the number of antitrust collective actions.24x Z. Juska, ‘The Impact of Contingency Fees on Collective Antitrust Actions: Experiments from Lithuania and Poland’, Review of Central and East European Law, Vol. 41, No. 3/4, 2016, p. 368, at 389. Another option is the availability of a conditional fee agreement, which is allowed in England and Wales. The lawyer takes the risks, but if the case is won, he or she can obtain a success fee in addition to the initial legal fee based on hourly billing. This reimbursement model was utilized in the above-mentioned Replica Football Shirts case, where the success fee was raised to 100%.25x See C. Leskinen, ‘Collective Antitrust Damages Actions in the EU: The Opt-In v. The Opt-Out Model’, Working Paper IE Law School WPLS 10-03, 2010, p. 10, available at: <http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1612731> accessed 15 January 2017. But this model is problematic in most EU member states, because financially poor representative organizations would be required to pay hourly legal fees to attorneys. Therefore, contingency fees are prioritized over conditional fees in the following discussion.

With regard to third party litigation, it may serve an auxiliary function in compensating victims. This is mainly because there are much less third party litigators compared with law firms. An even more important factor is that this type of litigation funding is uncommon in the EU context. So far the most popular financing of antitrust class actions has been on the basis of the Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs).26x For explanation, see C. Veljanovski, ‘Third-Party Litigation Funding in Europe’, The Journal of Law, Economics & Policy, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2012, p. 404, at 430-431. Under this model, investors purchase several claims with significant damages and then all litigation rights are transferred to SPV. But it is clear that the popularity of third party funding would increase if one of the scenarios was introduced. Regardless of the potential of third-party funding, the main emphasis in the following discussion is on contingency fees. These fees arguably have more possibilities of attracting a more active involvement of private parties. As proved in the US, this tool ensures that small-stakes collective actions are heard in courts.

However, it is true that all schemes are subject to criticism. One could argue that representation by a group lawyer, especially when contingency fees are combined with another deterrence-oriented remedy (especially an opt-out measure), may lead to abusive litigation by entrepreneurial lawyers. But the reality is that none of the scenarios is close to the American system, in which five deterrence-based remedies are combined. Notably, the measures of deterrence (two in each scheme) are proposed in a more lenient form than the American counterparts. Furthermore, the ‘loser pays’ principle is proposed as a common safeguard against litigation abuses of the representatives. But this measure is an insufficient prerequisite in itself to prevent frivolous actions, especially in countries where other sides’ costs are not high (like, the Netherlands). The safeguard mechanism is reinforced by the national ethical rules, which essentially act as a tool to enforce fair behaviour among lawyers.27x For example, an attorney acting against professional ethics can be removed from the bar. In order to mitigate the risks, additional safeguards can be introduced. The first one is a public tender system for legal services.28x For example, in Lithuania law firms are only qualified for a public tender if they meet minimum qualification requirements. Under this scheme, competing attorneys have to submit sealed bids indicating their proposed fees. If the appointed tender commission decides that fees are too low, the bidder is required to justify his proposal by providing detailed explanations of price components; such a scheme acts as the main safeguard against abuse of procedural rights. The price is important, but not crucial, for selecting the winner of the bid. The commission also takes into consideration the following factors: (i) the rationale; (ii) the quality; and (iii) the implementation plan. Another safeguard option is to qualify an ad hoc body that would be empowered to monitor the activities of the group lawyer and the group representative during the process.29x Such a committee would operate on a case-by-case basis. The members could be high-profile professionals, such as academics, economists, judges, etc.

However, none of the safeguards would ensure that one or another scenario is free from litigation abuses. In fact, it is hard to predict the outcome when contingency fees have not yet been tested in the EU’s collective redress schemes. For this reason, this article does not intend to show that one of the schemes should be introduced at the EU level. Instead, the principal aim is to assess the chances of these scenarios in achieving full compensation. In addition, there is a discussion on the potential of facilitated compensatory actions to contribute to public enforcement through an increased effect of deterrence.I First Scenario: Multiple Damages Combined with Contingency Fees and Third Party Funding

Determining multiple damages is not a revolutionary proposal at the EU level. In 2005, the European Commission proposed double damages for horizontal cartels in the Green Paper on damages actions.30x Commission, ‘Green Paper – Damages actions for breach of the EC antitrust rules’ COM (2005) 672 final. Also, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) asserted that the imposition of specific damages, such as exemplary or punitive damages, in response to harm caused by antitrust violations would not be contrary to the EU law if the principle of equivalence is respected.31x Joined Cases C-295/04 to 298/04 Vincenzo Manfredi and Others v. Lloyd Adriatico Assicurazioni SpA and Others [2006] ECR I-6619, paras. 98-99. However, after criticism that the EU was importing US litigation culture (especially from the business sector), the double damages were no longer included in the 2008 White Paper.32x Commission, ‘White Paper on Damages actions for breach of the EC antitrust rules’, COM (2008) 165 final. Following the same approach, the Directive on damages actions rejected punitive, multiple, or other kind of damages.33x Directive, supra note 1, Art. 3. Accordingly, antitrust collective schemes should be formed under the same provisions.

1 The Potential Justification for Damage Multipliers

Under this scenario, group formation is based on an opt-in remedy. This type of action entails significant costs, since the group needs to be organized. One of the major reasons why the group organization entails substantial expenses is that the typical adherence to the group is subject to formal requirements that exacerbate the financial costs. Furthermore, opt-in collective actions demand expensive awareness-raising campaigns in order to attract the affected parties to join the action. If the case is won, full compensation is unattainable in practice because the high organization and case management costs had already consumed the large portion of the award. This leads to a paradoxical outcome. The objective of full compensation demands the insurance of full compensation standards (actual loss and expectation loss), meaning that there is no space for undercompensating a victim. However, the action is predetermined to generate the award, which is much lower than the actual loss. Therefore, it clearly emerges that damage multipliers are needed to fill this gap of under-enforcement.

The same conclusion can be drawn from the above-mentioned Mobile Cartel case. So far, it has been one of few cases that have been brought on an opt-in basis. Most importantly, it has been the only case where tangible data about the opt-in collective antitrust litigation has been disclosed for public access. In that case, the French Competition Authority (NCA) imposed a record fine of 534 million euros on three mobile operators (Orange France, SFR, and Bouygues Telecom), alleging a price-fixing conspiracy. As a consequence, the consumer association UFC Que Chosir brought a follow-on collective damages claim. Table 2 summarizes the main figures of the litigation in the French case.34x UFC-Que Choisir, ‘Consultation de la Commission Europenne sur les Recours Collectifs Contribution De L UFC-Choisir’, 2011, available at: <http://ec.europa.eu/competition/consultations/2011_collective_redress/ufc_que_choisir_de_rennes_fr.pdf> (last accessed 14 January 2017).Table 2 An overview of the litigation statistics in Mobile cartelElement Outcome NCA fine 534 million euros Number of consumers opted in 12,530 out of ≈20 million (much less than 1%) Value of the claim 0.8 million euros (roughly EUR 60 per consumer participating in the claim) Case management expenses 2,000 hours to prepare the action. The costs were 0.5 million euros

The case attracted only 12,530 (much less than 1%) consumers to join the action, while the violation had a potentially negative impact on 20 million consumers. In spite of the small number of victims, the litigation involved 21 employees, 2,000 hours were needed to prepare the action, and it required issuing three cubic meters of documents.35x C. Hodges, The Reform of Class and Representative Actions in European Legal Systems: A New Framework for Collective Redress in Europe, Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2008, p. 84. As a consequence, the case management costs (0.5 million euros) consumed the majority of the potential recovery (0.8 million euros). On this point, it should be noted that the case was dismissed by the Paris Court of Appeal on the grounds that UFC Que Chosir “solicited consumer mandates via the internet.”36x M. Ioannidou, Consumer Involvement in Private EU Competition Law Enforcement, 1st edn, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 128. If the case was won, the damages would need to be distributed, thereby demanding extra costs. After all, if there would be some surplus, the class members would receive very low awards proportionally. Hence, this case proves that the enforcement of full compensation calls for some form of the damage multiplier.

However, there is no possibility to draw definite conclusions about the opt-in litigation costs in the entire antitrust landscape from this case alone. Primarily, the Mobile cartel case is representative in high-profile cartel actions, where representatives typically face similar issues when organizing the group. In addition, plaintiffs are facing a comparable burden of quantification and causation. But other types of infringements, such as abuse of dominance, cannot be directly compared with cartels. Cartel actions are typically more covert, and may thus require more costs and efforts to litigate them. In spite of the differences, all antitrust infringements share common features. First, the infringer usually targets the most vulnerable victims, such as ordinary consumers, who in fact have fewer capabilities (financial and legal) to bring a claim than large entities do. In these violations, the individual harm is typically low (for example, when consumers were buying an overpriced product), so the costs of the individual law-enforcement outweigh the expected benefits.37x It is also possible that a consumer can be a large corporation, which was buying an overpriced product. These entities may have more direct and more frequent relationships with the violator than an ordinary consumer would. In that case, the financial stake is determined to be higher than in ordinary consumer cases. Second, the antitrust violation causes harm to a multitude of victims, which are often spread out in different distribution chains. In such circumstances, the Mobile cartel case can only be considered a preliminary benchmark for assessing the potential impact of damage multipliers on the compensation goal.2 The Effectiveness of Compensation and Deterrence

It is very hard to define the balanced magnitude of a damage multiplier that would fully compensate, but not overcompensate, group members. Yet, given that the EU has already evaluated the possibilities for double damages, the effectiveness of doubling will be assessed first. The major question is whether double damages can ensure full compensation to victims who opted into the action. To start with, it should present the range of contingency fees that may be applicable in the EU context. In the US antitrust collective actions, contingency fees range between 15% and 33% (on average).38x See, e.g., B.T. Fitzpatrick, ‘An Empirical Study of Class Action Settlements and Their Fee Awards’, Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Vol. 7, No. 4, 2010, p. 811, at 818 (table 1); T. Eisenberg & G. Miller, ‘Attorneys’ Fees and Expenses in Class Action Settlements: 1993-2008’, Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2010, p. 248, at 262. This proportion also seems realistic in the EU, given that a larger percentage than 33% may breach the rules of attorney’s fear conduct, and a lower percentage than 15% may be economically unfeasible for private litigators. If the upper threshold is applied in the context of the Mobile cartel, the potential compensation of the group counsel (in an optimal scenario) would be around 0.5 million euros.39x The estimation was made under the following equation: 1.6 (million euros) × 0.33 = 0.528 (million euros). If this amount is deducted from the total award, damages doubling can both overcompensate and undercompensate group members. In this respect, three observations should be made.

First, if we suppose the ideal scenario when the court awarded damages requested (0.8 million euros), the total award after doubling would be 1.6 million euros. After the deduction of a contingency fee (around 0.5 million euros), the consumer fund would amount to 1.1 million euros. It therefore means that the ultimate recovery would exceed the damages for 0.3 million euros (1.1 million euros – 0.8 million euros). But, once the case is won, the distribution of damages requires additional administrative costs, which should not be high in opt-in collective litigation. Group members had already joined the group, and therefore their identities are clear when damages need to be distributed. Given this understanding, there is a chance that there will be some surplus of award when the entire case costs are deducted from the recovery. Therefore, there is a possibility of overcompensation. However, it should be acknowledged that the award of full damages is very optimistic and only possible in incidental cases. Second, a more realistic possibility is that the court will grant lower compensation than claimed. Under this approach, class members are unlikely to obtain full damages. Third, antitrust actions are likely to be settled. In that case, the full compensation is determined to fail, since defendants would aim at settling cases for lower than actual awards. Otherwise, the settlement is not so attractive.

After discussing three possible outcomes, it can be argued that the prospect of complete compensation is possible only in occasional cases. Another question is whether double damages induce more active involvement of representatives and group members, if it is combined with contingency fees. The increased participation of private actors would mean more actions brought and in turn more victims compensated.

A potential 33% contingency fee (when full damages are awarded) may generate the group counsel’s award of around 0.5 million euros, i.e., the same as litigation expenses of the UFC Que Chosir. In fact, it is too risky to engage in a contingency fee agreement, knowing that the litigation costs may equal the expected award. There would be no business in this case. Therefore, the combination of contingency fees and double damages would not significantly increase the lawyers’ incentives to invest in collective litigation. With regard to group members, double damages are not capable of attracting many more victims to join the action. Given that antitrust violations normally generate harm of low value, the incentive to join the action is not much increased if a victim, for example, can potentially receive 70% instead of 30% of the loss.40x For example, the individual harm was on average 60 euros in the Mobile Cartel and 20 pounds in the Replica Football Shirts. As a consequence, there is no big difference in incentive to join the action when the potential damages receivers considers whether they may receive 18 or 42 euros, or if they may receive 6 or 14 pounds. In particular, as a result of very low opt-in rates, the deterrence effect remains minimal or absent in this scenario. Most importantly, the magnitude of a likely penalty will be negligible if only few victims join the action. To conclude, this scenario has the ability to provide high proportional compensation to group members, but the size of the group is doomed to be very small. Due to the small size of the group, this scenario is not designed to deter infringers.

In conclusion, the potential of treble damages for achieving the objectives of compensation and deterrence should be noted. When applying the same data as in the Mobile cartel, a potential for overpayment can be foreseen if the case leads to a final court decision (Table 3).Table 3 The potential scenario of treble damagesAward (≈million euros) A 33% contingency fee (≈million euros) Award to victims (million euros) Potential surplus (≈million euros) The potential of overpayment Full award 2.4 0.8 0.8 0.8 Yes Partial award 2.2 0.7 0.8 0.7 Yes 2.0 0.7 0.8 0.5 Yes 1.8 0.6 0.8 0.4 Yes 1.6 0.5 0.8 0.3 Very high 1.4 0.5 0.8 0.1 Minimal 1.2 0.4 0.8 0 No 1 0.3 0.8< No surplus No Settlement 0.8< 0.3< 0.8< No surplus No

It can be seen that with an increase or decrease of the award, the payment to the class counsel and the potential surplus increase or decrease proportionally. On this point, it should be stressed that the additional costs for distributing damages in won cases are not included in Table 2, yet these expenses should not be high in case of opt-in (since victims are already identified). As a consequence, the overpayment is realistic when at least 60% (1.4 million out of 2.4 million) of full award is granted. In case of settlement, the overpayment is improbable. Furthermore, Table 2 shows that even in case of trebling the counsel’s potential award, it is not high enough to attract more active participation. After the deduction of litigation costs, the profit can potentially be 100,000 to 300,000 euros (in the best scenario).41x This amount is calculated when case-related costs are deducted from the recovery. It does not seem a very lucrative investment, because the expected profit hardly outweighs the risks. However, again, the Mobile cartel case provides only a preliminary benchmark for assessing treble damages in compensating victims and deterring wrongdoers. But the preliminary assessment suggests that treble damages have a high probability for overcompensation. For this reason, this article will no longer consider trebling in the EU context.II Second Scenario: Broader Discovery Rules in Indirect Purchasers’ Actions Combined with Contingency Fees

The CJEU previously brought uncertainty when striking a balance between the leniency programme and the private antitrust actions. In the Pfleiderer decision, the Court asserted that it was for the national courts to carry out a balancing test for the disclosure of leniency documents on a case-by-case basis.42x Case C-360/09 Pfleiderer AG v Bundeskartellamt [2011] ECR I-05161, para. 32. This ruling became a source of concern for whistle-blowers, because it was difficult to foresee how the national courts will treat the requests for disclosure. In order to protect the informers and the ones who had settled, the Directive on damages actions introduced the following limitations.43x Directive, supra note 1, Art. 6. First, it has restricted access to leniency statements and settlement submissions (‘black-listed’ documents). Second, the information prepared by a natural or legal person specifically for competition authority proceedings and settlement submissions that have been withdrawn, can only be disclosed after a competition authority has closed its proceedings (‘grey-listed’ documents). Third, other evidence or relevant categories of evidence can be disclosed at any time, but a claimant should make a reasoned justification supporting the plausibility of his or her claim. It is true that claimants are provided with some access to evidence in actions for damages. Nevertheless, the multi-layered safeguard policy raises doubts whether the incriminating material will be disclosed. An even worse factor is that national courts are granted the power to assess the proportionality of disclosure requests and whether confidential information is duly protected.44x Ibid., Art. 5(3). In fact, the access to evidence depends on how national courts will conduct a disclosure test, which needs to be performed on a case-by-case basis.

1 The Potential Justification for Broader Discovery Rules in Indirect Purchasers’ Actions

Facilitated access to leniency materials could be justified in antitrust collective actions when indirect purchasers face crucial evidence-gathering problems. It is clear that the further down the distribution chain victims are, the less evidence they have in order to prove the loss suffered. It is thus obvious that end consumers are a good target for antitrust offenders, because these victims are the least aware about the nature and extent of the harm. Therefore, access to leniency statements would significantly facilitate the chances of proving damages in consumer anti-cartel actions. Another argument in favour of better access to leniency statements stems from the fact that cartel meetings are typically covert, and proof of unlawful agreements may be destroyed.45x Industrial Bags Case (COMP/38354) Commission Decision of 30 November 2005, OJ L 282/41, paras. 140, 794. Also, the infringers are well aware about the violation, so they can impose additional enforcement costs on potential claimants so as to dissuade them from taking any actions.46x S. Peyer, ‘Cartel Members Only-Revisiting Private Antitrust Policy in Europe’, International and Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 60, 2011, p. 627, at 645. If broader discovery rules are not allowed in consumer actions (specifically, if they are indirect purchasers), representatives would lack interest in antitrust collective litigation, particularly if only opt-in actions are allowed. As a consequence, infringers will avoid the responsibility for the harm caused when claimants are consumers who stand at lower distribution levels.

The decision on whether to grant access to leniency materials or not could be made by national judges on a case-by-case basis. However, this type of disclosure may bring uncertainty about when and in what circumstances leniency materials will actually be disclosed, while simultaneously jeopardizing the functioning of leniency programme. For example, there is a risk that direct purchasers will free-ride on the efforts of indirect purchasers. In fact, the outcome of such disclosure is unpredictable. Further discussion on this matter is beyond the scope of this article. Rather, the principal aim is to assess whether and to what extent a more assertive disclosure measure would compensate indirect purchasers and subsequently deter wrongdoers.2 The Effectiveness of Compensation and Deterrence

In the absence of the damage multiplier, indirect purchasers cannot be fully compensated for harm suffered. Therefore, the major question is whether the combination of broad discovery rules and contingency fees can incentivize attorneys to bring more damages claims and to attract more victims to join the action than in a traditional opt-in claim.

To begin with, the disguised information, which is kept in leniency statements, provides fundamental insights for quantifying the harm caused by a rise in prices (‘overcharge’ and ‘volume effect’).47x For further discussion on the overcharge and the volume effect, see Practical Guide on Quantifying harm in actions for damages based on breaches of Article 101 or 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, accompanying the Communication from the Commission on quantifying harm in actions for damages based on breaches of Arts. 101 or 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, SWD(2013) 205, C(2013) 3440. In turn, it constitutes a useful basis for defining the affected group, and therefore increases the chances to pass the certification test. If the group is certified, the availability of incriminating evidence (such as, internal documents regarding agreed price increases and their implementation in practice) raises the chances of proving damages. It may therefore cause a shift of balance between the parties: on the one hand, a defendant – usually a large corporation – holding a key disguised material; and, on the other hand, plaintiffs – a group of consumers – who are normally distant from direct evidences. But will the access to leniency statements attract lawyers to invest in opt-in cases?

It is obvious that the investment is less risky when the incriminating evidence is available to plaintiffs. First, is easier to pass the certification test. Second, it is easier to prove the loss closer to full damages. Despite having a lot of potential to facilitate damages actions, a crucial issue is that facilitated access to evidence is unlikely to much increase the amount of victims when compared with a standard opt-in case. The facilitated discovery rules do not motivate consumers to participate in the action, because the potential compensation remains similar as in standard opt-in case. In addition, wide discovery rules do not ease the administrative burdens or formal necessities for individual consumers when they intend to adhere the action. For example, even if a consumer lost the proof of the purchase of the overcharged product (such as, a purchase check), he or she is still required to ‘include all essential documents’ in order to join the group.48x Leskinen, 2010, p. 10. In such circumstances, it is hard to imagine that rational actors will take the risk to act as representatives (especially investing in an information campaign) when the size of the group is determined to be small. The one, if not only, advantage of broader access is that indirect purchasers who have more extensive evidences of harm can prove damages more easily. However, the award of full compensation is highly distorted due to the need to compensate litigation costs in costly opt-in actions. Adding to the fact that the expected size of the group is small, the facilitation of the compensation objective is negligible in this scenario. This in turn does not deter wrongdoers. Like in the first scenario, the magnitude of the liability is rather anecdotal. To sum up, facilitated access to leniency documents increases the probability of success at the pre-trial and trial stages. However, there is little prospect that the group will be larger than in a typical opt-in action. Therefore, under this scenario, the expected effects would be minimal on full compensation, and most likely absent on deterrence.III Third Scenario: Opt-Out Schemes Combined with Contingency Fees

The previous scenarios indicate that an opt-in group formation combined with more assertive measures (double damages or broad discovery rules) can only marginally improve compensation. Despite the new opportunities, the reality is that very low participation rates are expected. Therefore, both scenarios fail to accomplish the stated goal of compensation. Following the basic logic, a very small number of victims receiving compensation (even if damages are close to full compensation) could not outbalance the fact that a large majority of victims receive nothing. Therefore, the size of the group is the principal factor in evaluating the implementation of the compensation goal. In fact, the success depends on whether a private antitrust model has a versatile tool for aggregating claims of different kinds. So far, the most effective device in gathering victims is an opt-out mechanism. This tool raises participation rates to maximum: the claim is brought on behalf of a defined set of victims unless someone declares to opt out.49x The US practice shows that opt-out rates are less than 0.2%. See T. Eisenberg & G Miller, ‘The Role of Opt-outs and Objectors in Class Action Litigation: Theoretical and Empirical Issues’, New York University Law and Economics Research Paper No. 04-004, 2004, p. 14, at 25, available at: <http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=528146> accessed 08 January 2017. There is no requirement to involve all victims, but claimants typically try to define the group as widely as possible, i.e., as close as possible to the optimal level. Such an aggregation remedy may result in millions of victims, thereby generating a great aggregate financial value. As a result, lawyers have much interest in investing in antitrust collective actions (even if they are of small-stakes), especially if contingency fee agreements are allowed.

1 The Potential Justification for Opt-Out Schemes

The major concern is that an opt-out vehicle may be in violation with Article 6 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, which allows for the parties to freely dispose their claims. However, the CJEU ruling in Eschig is seemingly supporting opt-out actions as long as victims can be adequately informed about their opt-out rights and can effortlessly withdraw from the group proceedings.50x Case C-199/08 Erhard Eschig v.UNIQA Sachversicherung AG [2009] ECR 1-8295, para. 64. For further discussion, see D.-P.L. Tzakas, ‘Effective Collective Redress in Antitrust and Consumer Protection Matters: A Panacea or a Chimera?’, Common Market Law Review, Vol. 48, 2011, p. 1125, at 1137. This basis is one of the reasons why opt-out antitrust actions are allowed in proactive member states. In this context, three countries should be noted. In Portugal, the first antitrust collective claim was brought against Sport TV, which held an illegal monopoly in the field of paid premium sports channels.51x Lisbon Judicial Court, Case No. 7074/15.8T8LSB. In the Netherlands, the Claims Funding International filed a suit against KLM, Air France, and Martinair in relation to the air cargo cartel.52x Claims Funding International plc. Press Release, 30 September 2010. In the UK, the first opt-out antitrust collective claim by the National Pensioners Convention, alleging the overcharge for mobility scooters by Pride Mobility Products, the UK’s largest supplier of mobility scooters.53x For the summary of the claim, see ‘Notice of an Application to Commence Collective Proceedings Under Section 47B of the Competition Act 1998’, Competition Appeal Tribunal, 2016, available at: <www.catribunal.org.uk/files/1257_Dorothy_Gibson_Summary_210616.pdf> (last accessed 25 April 2017). All the proceedings are still on-going. No one has yet reported that representatives in these cases have engaged in any type of abusive litigation.

2 The Effectiveness of Compensation and Deterrence

There is no doubt that an opt-out remedy is the most effective in collecting victims, as claims are brought on behalf of all potential victims. However, this does not mean that opt-out actions are very effective in compensating victims. The US experience indicates that around 35% – 90% of consumers receive some kind of compensation in automatic distribution settlements.54x See, e.g., Fitzpatrick & Gilbert, 2015; Pace & Rubenstein, 200819; Deborah Hensler et al., Class Action Dilemmas: Pursuing Public Goals For Private Gains, 1st edn, Santa Monica, CA, RAND Corporation, 2000. Under this procedure, monetary awards are automatically distributed to class members who do not express the willingness to withdraw from the action. But for the ones who receive recovery, the actual compensation is proportionally very low. Even in the most optimistic recovery scenario, automatic distribution settlements can only generate up to 70% compensation of the victim’s actual harm.55x Fitzpatrick and Gilbert, 2015, p. 787 (table 3). However, this study is primarily useful in cases relating to the disputes of overdraft bank fees. In contrast to antitrust cases, there is a comfortable electronic system that directly identifies victims. Another type of distribution is where class members are required to submit a valid claim form in order to obtain compensation (a so-called ‘claims made’ settlement). Under this model, only between 1% and 15% of class members receive compensation, and in some cases the proportion can be even lower than 1%.56x For the range between 1% and 15%, see Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2015, supra note 19; Pace & Rubenstein, 2008. For the range lower than 1%, see Mayer Brown, supra note 19. Although the number of class members receiving compensation is disappointingly small, the actual recovery rate is close or equals to 100%. This is notably because class members are only entitled to compensation if they submit a valid claim form proving their harm. After all, it does not change the fact that a large majority of victims receive no compensation.

Despite the failures, this scenario is the most effective in compensating victims. First, an opt-out remedy generates a significant aggregate financial value. Therefore, private actors are given the chance to reap substantial compensation. As a result, many more cases are going to be heard in courts in comparison with other scenarios. Second, the automatic inclusion mechanism ensures that a large number of victims will receive some form of compensation in automatic damages distribution cases. Even though many victims remain undercompensated, the final compensation value is greater compared to other scenarios where few class members obtain higher individual recoveries. In the following discussion, a comparison will be made of the potential value of compensation in each scenario (Table 4), using the illustrative example of the case where 1 million victims suffered the mean harm of 50 euros.Table 4 The analysis of the potential compensation valueScenario 1 Scenario 2 Scenario 3 Expected participation rate ≤1% <1% 35% (compensation rate) The potential number of victims involved in the action ≤10,000 (1% of victims) <5,000 (0.5% of victims) 350,000 (35% of victims) The value of the claim ≤1,000,000 (€) <500,000 (€) ≈17,500,000 (€) Individual recovery rate Up to 100% Up to 60% Up to 40% The total compensation value of the claim ≤800,000 (€) <350,000 (€) ≈7,000,000 (€)

For the sake of clarity, it should be noted that all calculations are based on the highest possible threshold, i.e., taking into account the most optimistic rates for participation and recovery. This approach allows for the evaluation of the achievement of compensation and deterrence under the most positive expectations. Following this approach, Scenario 1 is regarded to have a potential to aggregate a group consisting of 1% of victims (10,000). Yet, when considering the failures in France and the UK, a 1% rate would be very high for an opt-in antitrust collective action. But this proportion is possible when doubling of damages is combined with contingency fees. In that case, both victims and lawyers have more incentives to participate in the action: the former enjoy double compensation, while the latter enjoy double reimbursement. In contrast, Scenario 2 is less interesting to both sides, since there is no promise of higher awards than in ordinary opt-in claim. If an upper threshold is applied, a 0.5% participation rate seems feasible.

The estimations of recovery rates (the proportion of the damages delivered to group members in the light of damages suffered) are unpredictable as it is unclear how many victims would actually join the action. The ultimate individual compensation directly depends on what the aggregate value of the claim would be.57x The size of the group determines the case-related costs and contingency fees. Therefore, it directly affects how much money will be deducted from the total award. The larger the group, the more possibilities for larger individual compensation. However, the proposed rates in scenarios 1 and 2 (up to 100% and 60% respectively) seem realistic when compared to the magnitude of the potential award.58x In Scenario 1, the potential of 100% compensation can be drawn from the discussion in Section 1.2. In Scenario 2, this data can be found when, for instance, analysing the following scenario. If 0.3% of victims (3000) join the action, the actual value of the claim would be 150,000 euros. When a 30% contingency fee was deducted from the award, the leftover would be 100,000 euros. When this amount is distributed to class members, each recovery could be potentially around 30 euros (around ≈60% of the recovery). When the potential participation rates are taken into account, none of the scenario would be worth more than 1 million euros.

With regard to Scenario 3, the representative compensation rates (when class members receive some kind of compensation) can be drawn from the US jurisdiction. As mentioned before, the compensation rates in consumer cases range between 35% and 90%, but the most relevant data for the antitrust case would be 35%.59x See Pace & Rubenstein, 2008. Authors argue that “the smallest distribution rates tended to have class sizes of several hundred thousand class members.” And indeed antitrust cases fell under this category, because typical antitrust violation lasts for years. It is estimated that the average duration of a cartel is 5.7 years. See F. Smuda, ‘Cartel Overcharges and the Deterrent Effect of EU Competition Law’, Centre for European Economic Research, Discussion Paper No. 12-050, 2012, pp. 19-21, available at: <http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2118566> (last accessed 10 February 2017). It would therefore mean that around 350,000 victims are expected to receive some kind of compensation under the Scenario 3. But, again relying on the US results, these victims could only expect up to 40% recovery rate of their loss.60x There is a lack of data on this issue. The only relevant study is Fitzpatrick & Gilbert, 2015. However, it estimated the recovery rates for small-stakes class actions relating to the disputes of bank overdraft. It is highly unlikely that these optimistic rates would be applicable in case of antitrust. As a result, the total (optimistic) compensation value could potentially be around 7 million euros.

Admittedly, this study reflects only a hypothetical scenario. In fact, the rates (participation, compensation, and recovery) fluctuate from case to case. However, this does not change the key factor that the compensation value in Scenario 3 is always considerably higher than in other scenarios. This fact would not change significantly even if the case-related costs would be higher in an opt-out litigation, or if the participation rates would be higher (e.g., 2% or 3%) in other scenarios. The difference between the compensation values is simply too large.

These results also demonstrate that Scenario 3 scores the best marks in deterring infringers. Under this scenario, the aggregate value of multiple claims (even if the individual harm is low) can total millions of euros. This, in turn, forces defendants to internalize more of the negative effects caused to victims, thereby adding a side effect on deterrence. Another important factor is that a large majority, if not all, of the decisions by DG Competition in consumer cases will be followed up with collective damages claims. The European Commission typically engages in high-profile cases where the violation negatively affects a wide range of victims, often across the EU member states. Therefore, there is a high interest for private actors to sign a contingency fee agreement, which, in case of success, would lead to a significant award. At the national level, there is no guarantee that all the NCA’s fining decisions will be followed by the actions of private litigators. For example, regional cases or cases in small countries may produce low combined financial loss. Therefore, in the absence of damage multipliers, the risks may be too high for utilizing contingency fees in lower profile cases. This undercuts the deterrence objective.

To conclude, this scenario is the best suited to facilitate compensation. Even though the achievement of full compensation for individual victims is significantly diminished, a very large portion of victims can expect some form of compensation. In addition, rational infringers have to consider the increased probability of being punished by private parties in follow-on actions. Nevertheless, deterrence is diminished in lower magnitude cases. After all, in comparison with other scenarios, this scenario facilitates the deterrence in best terms. -

D The Best Possible Compensatory Mechanism of Antitrust Collective Actions: Checks and Balances

The results show that the case for full compensation is weak in all scenarios. It is predetermined that either very few victims will receive compensation, or that many victims will obtain very low proportional recovery. It can be argued that the compensation largely fails as a goal in these scenarios, because the principle of full compensation demands a very wide antitrust enforcement model. If the EU is inclined to shape private antitrust enforcement under full compensation, there is no other choice than to combine the above-discussed scenarios. As a result, the following analysis will design the best possible mechanism that is within the limits of the enforcement of full compensation and that is within the legal traditions (at least in some member states). However, there is no intention to raise the debate about whether it would attract or not the litigation abuses announced in US class actions. But, given that the ‘loser pays’ principle could be combined with other measures (less forceful tools than American counterparts, national rules of ethics, and an ad hoc case monitoring body), it is considered that the following proposal has sufficient grounds.

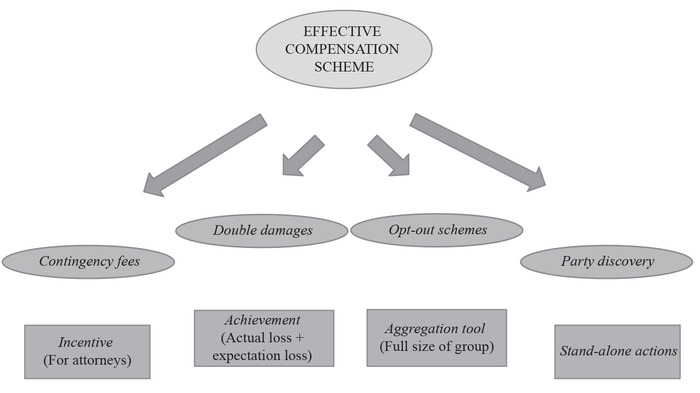

I The Design of the Best Possible Compensation Mechanism

When designing this model, two major components have to be combined. First, each victim should be able to obtain full compensation (actual harm, loss of profit, and interest). Second, the aggregation device should be capable of reaching both direct and indirect purchasers, regardless of how distant they are from the violation. In order to ensure both components, the enforcement mechanism should be an aggregate of three indispensable elements: contingency fees, opt-out schemes, and double damages. Furthermore, the scheme should secure that sufficient measures are introduced for incentivizing stand-alone actions. These measures are interrelated and complement each other towards the achievement of the best possible compensation. The scheme (hereinafter ‘Proposal’) is illustrated in Chart 1.

The most possible compensation scheme (Proposal)

First, it should be stressed that two determinants – double damages and opt-out schemes – are directly related with the implementation of the best possible compensation. Double damages are necessary to cover the enforcement costs of full compensation: to compensate full loss (actual loss plus expectation loss) to group members and to recompense high case-related costs (administrative, expert etc.). An opt-out mechanism is essential in reaching direct and indirect purchasers, especially when the individual harm is small. Indeed, only an automatic inclusion of victims can achieve this objective. Yet, it is clear that compensating victims would fail to a large extent if contingency fee agreements were not involved in the Proposal. These fees are indirectly enhancing the compensation mechanism through the increased incentives for lawyers to invest in complex antitrust group actions. In fact, as more collective action lawsuits are brought to the court, more victims are provided with compensation. As previously discussed, while public authorities are economically too weak in many EU member states, attorneys have more financial resources and legal expertise to litigate antitrust collective actions.

Contrary to Scenario 2, the Proposal welcomes the protection of leniency statements. The EU leniency policy has proved to be successful in fighting cartels.61x See, e.g., A. Stephan, ECJ Ruling in Pfleiderer Heightens Concerns about Encouraging Private Enforcement’, Competition Policy Blog, 2011, available at: <https://competitionpolicy.wordpress.com/2011/06/23/ecj-ruling-in-pfleiderer-heightens-concerns-about-encouraging-private-enforcement/> (last accessed 10 February 2017) (noting that around two thirds of European cartel violations are uncovered after the leniency). On this issue it is further discussed by the same author in ‘Four key challenges to the Successful Criminalization of Cartel Laws’, Journal of Antitrust Enforcement, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2014, p. 333. It would be highly unjustifiable if the leniency programme would be put at risk when the incriminating material can potentially be disclosed under the current disclosure mechanism. It allows access to explanatory evidence, such as prices, sales volumes, profit margins, or costs.62x In many cases, this type of documents will be under the category of ‘white-listed’ documents (Directive, supra note 1, Art. 6). In turn, it facilitates quantification of overcharges caused by antitrust infringements.

Another viewpoint is that the Proposal should provide more basis for stand-alone actions. In the present form, stand-alone claims are only facilitated by the general rules on disclosure.63x Directive, supra note 1, Arts. 5(2)-(5). A crucial issue is that national courts are required to limit the disclosure by performing the proportionality test on a case-by-case basis, i.e., the court-ordered disclosure. In fact, no one can predict how a national court will treat requests for access. In order to increase the motivation to bring stand-alone actions, the EU should consider the disclosure more directly as a party-initiated scheme in the US.64x See, e.g., Crane, 2010, pp. 700-701. Within the respective legal frameworks of member states, the claimant should be granted disclosure to all evidence available that can help quantifying the harm in stand-alone damages actions. The court in this respect should only observe the exchange of documents, and should only interact in exceptional circumstances; for example, when the claimant undermines the proportionality of disclosure measures. However, such disclosure may raise difficulties for the courts to determine the balance between feasible and unfeasible disclosure requests. As a safeguard against frivolous access to evidence, the set of material that is accessible to claimants can be defined. The availability of this list would ensure the extent of disclosure even before the claimant starts an action.II The Best Possible Compensation v. Full Compensation: A Study

The Proposal discussed above should score many points in compensating victims. Thus, the major question needs to be answered: to what extent can the best possible collective redress mechanism fulfils the objective of full compensation?

To begin with, it should be emphasized that many victims would be able to obtain compensation under the proposed model. But the objective of compensation should provide not only some form of award, rather it has to deliver full compensation to direct and indirect purchasers. However, for various reasons, the achievement of full compensation is determined to fail to a large extent, even under the principles of the most feasible collective antitrust redress scheme.

First, an opt-out remedy is imperfect in reaching indirect purchasers. But the primary fault is not of an aggregation mechanism, rather it is the fault of the highly complex nature of competition law infringements. The antitrust overcharge can cause widespread harm at different levels of distribution, making the identification of victims a very complicated task. A good example is the Canadian case Sun-Rype Products Ltd v Archer Daniels Midland Company.65x 2013 SCC 58 [2013] 3 S.C.R. 545. The claim alleged that the defendants unlawfully fixed the price of high fructose corn syrup sold to direct purchasers and that some of the overcharge was passed on to indirect purchasers, mainly end consumers. On the basis of an infringement, it was obvious that an overcharge was passed to indirect purchasers, but it was impossible to determine the direct relationship between indirect purchasers (end consumers) and overcharged products.66x Ibid., para. 65. Furthermore, class members may fail to obtain a compensation award due to the complex recovery procedure. For example, the US favours a multifaceted approach (sometimes even requiring notarization67x W.M. Ackerman, ‘Class Action Settlement Structures’, Federation of Defense & Corporate Counsel, 2013 Winter Meeting, Westin La Cantera Resort, San Antonio, Texas, 2013, p. 5, available at: <www.thefederation.org/documents/13.Class%20Action-Structures.pdf> (last accessed 15 January 2017). ) in order to prevent frivolous litigation.

Second, many collective actions are likely to be settled when the certification stage is passed.68x Taking the US example, more than 90% of cases are settled. See R. Wasserman, ‘Cy Pres in Class Action Settlements’, Southern California Law Review, Vol. 88, 2015, 2015, p. 97, at 102 (citing T.E. Willging & E.G. Lee III, ‘Class Certification and Class Settlement: Findings from Federal Question Cases, 2003-2007’, University of Cincinnati Law Review, Vol. 80, 2011, p. 315, at 341-342; T.E. Willging & S.R. Wheatman, ‘Attorney Choice of Forum in Class Action Litigation: What Difference Does It Make?’, Notre Dame Law Review, Vol. 81, 2006, p. 591, at 647). Indeed, the settlement agreement is attractive for the participants of collective actions. Defendants often find it prudent to settle a class action rather than continue costly legal proceedings with unpredictable jury trial: a loss might put a defendant out of business. The class counsel, who is acting under the contingency fee agreement, is always happy to settle rather than continue very long and complex collective actions. In the end, the attorney receives a percentage of the recovery, which is typically high, given that the size of the group is large under an opt-out action. The judge has no reason not to end a complex antitrust case (often requiring economic assessments) when both parties agree on terms. As mentioned in Scenario 1, a doubling of damages is highly unlikely in settlements; the awards should be lower than actual damages. Although the aggregation mechanism is not jeopardized, the award of full compensation to individual victims is strongly diminished. One solution would be to cap the settlement awards for amounts higher than the actual damages. However, the issue is that defendants might refrain from settling at all. Likewise, it may lead to dissuasive effects for the plaintiff side, given that there would be no intention to bring antitrust actions, which typically last for many years. In that case, the group lawyer should assess the risks of losing the long-lasting case: the money invested, compensating the other side’s costs, and receiving no compensation from group members.

Third, the Proposal is insufficient to increase the rate of stand-alone actions to the extent that it would fill the gap of under-enforcement of public enforcers. In fact, lawyers are rational actors who deal with cases that have a high chance of success. The combination of measures in the Proposal does not motivate private litigators to take actions of any potential cartel violation. Even if the disclosure is facilitated in stand-alone actions, cartel violations remain covert, thereby requiring comprehensive investigative tools. On this point, it ought to be stressed that US class actions are still more forceful than the Proposal. First, the ‘loser pays’ principle is abandoned in the US mechanism, and instead the one-way fee shifting is allowed. Second, the predictability of jury trials creates a strong ground for the plaintiffs’ lawyers to blackmail the defendants. But regardless of that, it is of utmost importance to note that only up to 33% of cartel violations are detected in the United States.69x Connor & Lande, 2012, pp. 486-490. It is hard to imagine that the Proposal would under any circumstances have more impact on detection than its counterpart in the United States.

To sum up, it must be borne in mind that the best possible mechanism in the EU context has been presented. Despite this mixture, the achievement of full compensation is predetermined to fail. This is because violations of competition law are so complex and disguised that there is no rational decision to identify all victims: both direct and indirect purchasers. In addition, victims, who are detected and automatically involved in the group, are unlikely to be fully compensated due to high litigation costs, the low worth of settlements, and costly distribution of damages. It demonstrates that regardless of what the EU collective redress scheme is, the failure of full compensation to antitrust victims seems predetermined. Yet the extent of the failure is very different. On the one hand, if collective redress schemes are designed following the Proposal, many victims, but not all, can expect compensation (albeit not full compensation). On the other hand, if a collective redress mechanism is framed following the proposed principles of the Recommendation, the failure would be absolute: very few (if any) actions will be brought on behalf of antitrust victims. Therefore, most (if not all) victims will remain uncompensated. With regard to deterrence, the Proposal would ensure some sort of discouragement to potential wrongdoers. This is due to the increased magnitude of the liability and the ensured follow-on litigation. However, the full effectiveness of deterrence is diminished, because stand-alone actions would be rare. Therefore, rational wrongdoers would first consider how effective public enforcement is, while private enforcement would be a secondary measure in the sequence of deterrence. -

E The Potential Legislative Measure in the Future

Despite all its failures, antitrust collective litigation should not be denied under any circumstances. It is an indispensable element to any reform of damages actions. In order to start an era of antitrust collective litigation across the EU, legislators should follow two guiding principles when taking another step in the field.

First, collective redress schemes should be foremost framed at defending the rights of vulnerable victims: indirect purchasers with small damages and indirect purchasers. If there was no effective collective redress mechanism, these claims would probably never be brought to the courts, as individual litigation is unprofitable financially. On the contrary, the current EU mechanism is useful primarily for large corporations, which were harmed as direct purchasers. Ironically, these corporations have been suing for damages even before the adoption of the Directive on damages actions.70x BarentKrans, ‘Cartel Damages Claims in Europe’, 2015. In 2015, there have been 64 pending cartel damages claims in the EU.

Second, EU legislators should admit that the current conservative approach to collective redress is bound to fail to a large extent in enforcing full compensation in competition law. Given that only few, and in countries with assertive measures on collective litigation, actions will be brought to the courts, a vast majority of vulnerable victims are fated to remain uncompensated. If this failure was recognized, the next step for the EU would be to attempt incorporating assertive measures for making collective actions viable across the union. Indeed, the member states’ experiences with opt-out actions might serve as an inspiration for the EU that assertive aggregation tools are possible and necessary in the EU context. Moreover, the stimulus can be considered the availability of assertive funding tools in member states: third party funding and contingency fees.71x For the discussion on contingency fees in the EU member states, see Juška, 2016, p. 368. In addition, as shown before, multiple damages do not inherently lead to overcompensation of victims.

Considering all the criticism surrounding the policy on collective redress, it should be considered a big success if the EU adopted a sector-specific recommendation (a non-binding measure) on antitrust collective litigation, yet this time proposing more forceful tools than the ones proposed in the Recommendation in 2013. The following measures may be proposed:Flexibility/encouragement for opt-out schemes;

Flexibility/encouragement for multiple damages;

Flexibility/encouragement for private funding (third party litigation and contingency fees);

Encouragement for stand-alone actions.