-

A Introduction

The aim of this article is to offer a reflection on asymmetry as an instrument of differentiated integration1x As Fossum pointed out, differentiation and differentiated integration are not synonymous: “These developments suggest a need to distinguish differentiation from differentiated integration. We might understand differentiation as a wider concept that includes, yet goes beyond, differentiated integration. In other words, it encompasses traditional understandings of differentiated integration as mainly consisting of the same integration only at different speeds. Yet it also includes two new differences between member states that are likely to be wider and more lasting: first, cases where some states integrate more closely whilst, at the same time and for connected reasons, others disintegrate from their previous levels of involvement with the Union; and second, cases where even notionally full members come to be regarded as having different membership status”. J.E. Fossum, ‘Democracy and Differentiation in Europe’, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2015, pp. 799-815, at 800. in the current phase of the EU integration process. In order to do so, this article is divided into four parts: in the first part I shall clarify what I mean by asymmetry as an instrument of integration relying on comparative law. This comparative exercise is particularly useful because it allows us to acknowledge the strong integrative function performed by asymmetry in contexts different from but comparable to the EU system. In the second part I shall look at EU law and recall the main features of asymmetry in this particular legal system. In the third part of the article I shall look at the implications of the financial crisis, which has increased the resort to asymmetric instruments. In the last part I shall deal with some recent proposals concerning the differentiated representation of the Eurozone.

Leuffen et al.2x D. Leuffen, B. Rittberger & F. Schimmelfennig, Differentiated Integration. Explaining Variation in the European Union, Basingstoke, Palgrave 2013. have defined the EU as a “system of differentiated integration” and have argued that “differentiation is an essential and, most likely, enduring characteristic of the EU. Moreover, differentiation has been a concomitant of deepening and widening, gaining in importance as the EU’s tasks, competencies and membership have grown”.3x F. Schimmelfennig, D. Leuffen & B. Rittberger, ‘The European Union as a System of Differentiated Integration: Interdependence, Politicization and Differentiation’, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2015, pp. 764-782: “We distinguish two types of differentiation that we term vertical and horizontal differentiation. Vertical differentiation means that policy areas have been integrated at different speeds and reached different levels of centralization over time. Horizontal differentiation relates to the territorial dimension and refers to the fact that many integrated policies are neither uniformly nor exclusively valid in the EU’s member states. Whereas many member states do not participate in all EU policies (internal horizontal differentiation), some non-members participate in selected EU policies (external horizontal differentiation)”.

A system of differentiated integration can be otherwise described as “an organizational and member state core but with a level of centralization and territorial extension that vary by function”.4x Leuffen 2013, p. 10.

These lines are emblematic of a progressive attention paid to differentiation and are consistent with those views that describe the EU as characterized by cultural and historical diversities (that are conceived as a factor of spiritual richness rather than a danger for the common path).

Another confirmation of this is Article 4.2 of the TEU, which expressly codifies nowadays the necessity to preserve the constitutional diversity characterizing the EU when stating that the EU shall respect “their national identities, inherent in their fundamental structures, political and constitutional, inclusive of regional and local self-government”.

Against this background asymmetry can be conceptualized as an instrument of differentiated integration useful to guarantee unity without jeopardizing the constitutional diversity that inspires the European project. However, despite this, “differentiated forms of European integration tend to be viewed skeptically by many scholars and policy-makers”.5x A. Warleigh-Lack, ‘Differentiated Integration in the European Union: Towards a Comparative Regionalism Perspective’, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2015, pp. 871-887. Indeed, frequently, differentiated integration has been seen as a “a challenge to the authority of the Union; to its telos; to the unity of its policies, laws and institutions; and to any prospect of it developing into a political community based on shared rights and obligations of membership”.6x As Lord recalls, see C. Lord, ‘Utopia or Dystopia? Towards a Normative Analysis of Differentiated Integration’, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2015, pp. 783-798; and “differentiated integration has been transformed from taboo to one of the main sources of pragmatic compromise in EU politics”; see also R. Adler-Nissen, ‘Opting Out of an Ever Closer Union: The Integration Doxa and the Management of Sovereignty’, West European Politics, Vol. 34, No. 5, 2011, pp. 1092-1113.

The literature on differentiated integration and multi-speed Europe is huge,7x A.C.-G. Stubb, ‘A Categorisation of Differentiated Integration’, Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 34, No. 2, 1996, pp. 283-295; Warleigh-Lack 2015, p. 876. and this piece is not a review article; rather, the goal of this introduction is to recall the most important terms of the debate, in order to clarify its scope of analysis. The idea of differentiated integration and that of asymmetry – to be conceived as an instrument of differentiated integration – have been extended and adapted to many different processes by scholars over the years, but to avoid misunderstanding I would like to make clear that in this work I shall analyse those forms of asymmetries that are allowed and carried out only when respect for an untouchable core of integration is guaranteed.

This is crucial to conceive asymmetry as an instrument of integration. Against this background, flexibility gives added value to the life of a political system only when the identity of this system can be preserved; otherwise, flexibility would lead to a revolution in a technical sense, i.e. a transformation of the identity of the legal system, or in Kelsenian terms a new basic norm and the interruption of the chain of validity.8x H. Kelsen, General Theory of Law and State, New York, Russell and Russell 1945, pp. 115-122; H. Kelsen, The Pure Theory of Law, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press 1970, pp. 208-214. To avoid this, a legal system allowing asymmetry presents some constitutional safeguards, as we will see. -

B What Can We Learn from Comparative Law?

Asymmetry has been frequently experimented with within federalizing processes,9x F. Palermo, ‘Divided We Stand. L’asimmetria negli ordinamenti composti’, in A. Torre et al. (Eds.), Processi di devolution e transizioni costituzionali negli Stati unitari (dal Regno Unito all’Europa), Torino, Giappichelli 2007, pp. 149-170; R.L. Watts, A Comparative Perspective on Asymmetry in Federations, 2005 (Asymmetry Series IIGR, Queen’s University), available at: <www.iigr.ca/pdf/publications/359_A_Comparative_Perspectiv.pdf>. especially in those federal or quasi-federal contexts characterized by the coexistence of different legal and cultural backgrounds (Canada, for instance). One should take this into account before conceiving, for instance, enhanced cooperation as a form of ‘constitutional evil’ conducive to a ‘disintegrative’ multi-speed Europe.

On the contrary, asymmetry might even serve as an instrument of constitutional integration, as comparative law shows. For instance, flexibility and asymmetry are two of the most important features of Canadian federalism, elements partly explicable by taking into account the cultural and economic diversity present in the territory: “Federal symmetry refers to the uniformity among member states in the pattern of their relationships within a federal system. ‘Asymmetry’ in a federal system, therefore, occurs where there is a differentiation in the degrees of autonomy and power among the constituent units”.10x Watts 2005. However, asymmetry does not refer to mere differences of geography, demography or resources existing among the components of the federation or to the variety of laws or public policies present in a given territory.11x The word asymmetry has acquired a variety of meanings: when talking about asymmetries one can distinguish between financial and constitutional asymmetry, or between de jure and de facto asymmetry. De jure asymmetry “refers to asymmetry embedded in constitutional and legal processes, where constituent units are treated differently under the law. The latter, de facto asymmetry, refers to the actual practices or relationships arising from the impact of cultural, social and economic differences among constituent units within a federation, and, as Tarlton noted, is typical of relations within virtually all federations” (Watts 2005).

The debate on the concept of asymmetry originates from comparative studies in the 1960s after the publication of a seminal article by Charles Tarlton in the Journal of Politics,12x C.D. Tarlton, ‘Symmetry and Asymmetry as Elements of Federalism: A Theoretical Speculation’, Journal of Politics, Vol. 27, No. 4, 1965, pp. 861-874. whereby the author tried to fill a gap highlighting “a principal weakness in theoretical treatments of the concept of federalism”.13x Ibid., p. 861. On that occasion, Tarlton introduced two key concepts in the study of federal systems:Two concepts […] can be introduced and their general content suggested here. The first, the notion of symmetry refers to the extent to which component states share in the conditions and thereby the concerns more or less common to the federal system as a whole. By the same token, the second term, the concept of asymmetry expresses the extent to which component states do not share in these common features. Whether the relationship of a state is symmetrical or asymmetrical is a question of its participation in the pattern of social, cultural, economic, and political characteristics of the federal system of which it is part. This relation, in turn, is a significant factor in shaping its relations with other component states and with the national authority.14x Ibid.

Despite the very broad definitions given to these two concepts, the piece by Tarlton has become a classic, a mandatory reading, where one can find many of the intuitions developed in the current debate about flexibility and uniformity in multi-tiered (not only in fully fledged federal) systems, including a certain scepticism towards asymmetrical arrangements that we will find even in European studies.15x Ibid., p. 874. As Burgess16x M. Burgess, ‘Federalism and Federation: A Reappraisal’, in M. Burgess & A.G. Gagnon (Eds.), Comparative Federalism and Federation, Toronto, Toronto University Press 1993, pp. 3-14; M. Burgess & F. Gresse, ‘Symmetry and Asymmetry Revisited’, in R. Agranoff (Ed.), Accommodating Diversity: Asymmetry in Federal States, Baden-Baden, Nomos Verlag 1999, pp. 43-56. pointed out, within two broad types of preconditions of asymmetry (called ‘socio-economic’ and ‘cultural–ideological’ preconditions), it is possible to refer to a variety of factors that might lead a given polity to rely on asymmetry (political cultures and traditions, social cleavages, territoriality, socio-economic factors, demographic patterns). When listing the pros and cons of asymmetry Bauböck recalls that: (1) asymmetry can affect cohesion, that is “the glue binding the component parts together”,17x R. Bauböck, ‘United in Misunderstanding? Asymmetry in Multinational Federations’, 2001 (ICE Working Paper series), available at: <http://eif.univie.ac.at/downloads/workingpapers/IWE-Papers/WP26.pdf>. (2) asymmetric powers can translate “unequal representation of citizens in federal government and thus can be seen to violate a commitment to equal federal citizenship”18x Ibid. and (3) asymmetry may be perceived as a threat to the quality of the democratic debate, making the polity less understandable by citizens19x “Highly asymmetric federations become opaque for their citizens”, Bauböck 2001. and creating “incentives for bargaining that will generate even more asymmetry”.20x Bauböck 2001.

At the same time asymmetry is a resource for a polity that wants to recover disadvantaged minorities and that respects the equal dignity of its components. In other words, asymmetry is a game between centripetal and centrifugal forces, and here again one can find interesting clues from comparative studies: indeed the debate on the possible negative implications of asymmetry leads to the identification of the existence of a constitutional core of principles and values whose respect makes asymmetry ‘sustainable’: this is also the rationale of asymmetry in EU law as, for instance, we will see when dealing with Article 326 TFEU.

As comparative law shows, asymmetry works as a safety valve for some tensions generated by the coexistence of different cultures; Canada is emblematic from this point of view, and a good example of this is given by social policies, as we will see.

While comparative lawyers still treat asymmetry as an exception in the life of federal polities (and this can be explained by conceiving the foedus as a contract between parties put on an equal footing), actually, this concept has regularly acquired a key role in the history of federalism; in other words, today asymmetry is the rule rather than the exception in this field.21x F. Palermo, ‘La coincidenza degli opposti: l’ordinamento tedesco e il federalismo asimmetrico?’, 2007, available at: <www.federalismi.it/nv14/articolo-documento.cfm?artid=6991>. -

C Asymmetry in EU Law

As mentioned at the beginning of the article, when dealing with differentiated integration scholars in EU studies also recall other phenomena that are partly connected with the focus of this article.22x See, for instance, the examples of differentiated integration treated by F. Tekin, ‘Opt-Outs, Opt-Ins, Opt-Arounds? Eine Analyse der Differenzierungsrealität im Raum der Freiheit, der Sicherheit und des Rechts’, Integration, No. 4, 2012, pp. 237-257 as translated into English by W. Wessels, ‘How to Assess an Institutional Architecture for a Multi-level Parliamentarism in Differentiated Integration?’, 2012 (Directorate General for Internal Policies Policy Department C: Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs), available at: <www.europarl.europa.eu/document/activities/cont/201210/20121003ATT52863/20121003ATT52863EN.pdf>.

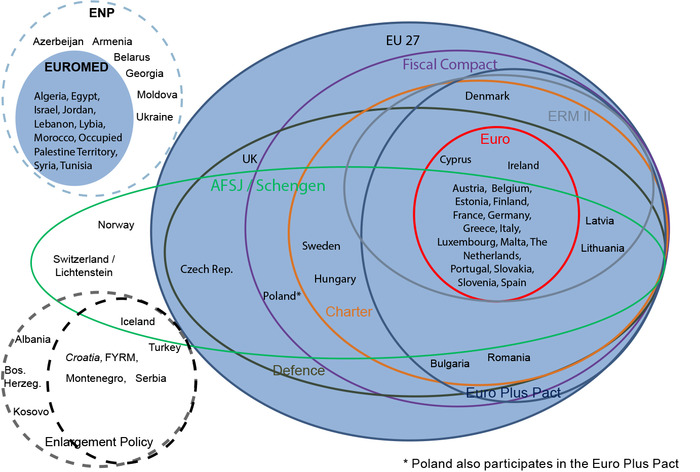

For instance, by adopting a broader notion of differentiated integration, in 2012 Funda depicted the current state of differentiated integration as in Figure 1.

Figure 1 confirms the importance that integrated differentiation has in the European integration process. Scholars have conducted in-depth studies of the contours acquired by the idea of differentiation in EU law and its main sources, distinguishing several models.23x M. Avbelj, ‘Differentiated Integration – Farewell to the EU-27?’, German Law Journal, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 191-212, at 193-194. Others have harshly criticized the asymmetric option as being incompatible with an integration process. Finally, another group of authors has insisted on the positive implications of a multi-speed Europe to overcome the difficulties present in the enlarged Union.24x J.-C. Piris, ‘It Is Time for the Euro Area to Develop Further Closer Cooperation Among Its Members’, 2011 (Jean Monnet Working Paper 5/2011), available at: <http://centers.law.nyu.edu/jeanmonnet/papers/11/110501.html>.

I shall limit my attention to some of these phenomena only (I will not look, for instance, at external relations), by adopting a narrower concept of asymmetry. The EU already knows some forms of asymmetry:25x Watts, for instance, mentions the EU in his writings on asymmetry: R.L. Watts, ‘The Theoretical and Practical Implications of Asymmetrical Federalism’, in R. Agranoff (Ed.), Accommodating Diversity: Asymmetry in Federal States, Baden-Baden, Nomos Verlag 1999, pp. 24-35, at 29. the opt-out mechanism,26x L. Miles, ‘Introduction: Euro Outsiders and the Politics of Asymmetry’, Journal of European Integration, Vol. 17, No. 3, 2005, pp. 3-23. the open method of coordination27x F. Scharpf, ‘The European Social Model: Coping with the Challenges of Diversity’, 2008 (MPIfG Working Paper 02/8), available at: <http://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/mpifgw/028.html>. See also M. Dawson, ‘Three Waves of New Governance in the European Union’, European Law Review, Vol. 36, No. 2, 2011, pp. 208-226. and enhanced cooperation28x J.M. Beneyto & J.M. González-Orús (Eds.), Unity and Flexibility in the Future of the European Union: The Challenge of Enhanced Cooperation, Madrid, CEU–S. Pablo 2009, available at: <www.ceuediciones.es/documents/ebookceuediciones1.pdf> and C.M. Cantore, ‘We’re One, but We’re Not the Same: Enhanced Cooperation and the Tension Between Unity and Asymmetry in the EU’, Perspectives on Federalism, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2011, pp. E-1-E-21. See in general, G. de Búrca & J. Scott (Eds.), Constitutional Change in the European Union, Oxford, Hart Publisher 2000. are just some examples.Differentiated Integration in the EU Source: F. Tekin, ‘Opt-Outs, Opt-Ins, Opt-Arounds? Eine Analyse der Differenzierungsrealität im Raum der Freiheit, der Sicherheit und des Rechts’, Integration, No. 4, 2012, pp. 237-257 as translated into English by W. Wessels, ‘How to Assess an Institutional Architecture for a Multi-level Parliamentarism in Differentiated Integration?’, 2012 (Directorate General for Internal Policies Policy Department C: Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs), available at: <www.europarl.europa.eu/document/activities/cont/201210/20121003ATT52863/20121003ATT52863EN.pdf>. The opt-out mechanism has been defined as “a form of defection in the EU”.29x M. Sion, ‘The Politics of Opt-Out in the European Union: Voluntary or Involuntary Defection?’, IWM Junior Visiting Fellows’ Conferences, Vol. XVI, No. 7, 2004, available at: <www.iwm.at/wp-content/uploads/jc-16-07.pdf>. An example of an opt-out is the non-participation of the UK in the third stage of economic and monetary union (EMU).30x “Treaty opt-out (as the UK and Danish opt-out of the common currency) occurs when most of the Member States in the EU agree to advance the integration process, and therefore negotiate in an Intergovernmental Conferences (IGC) to change the common EU treaties, but encounter a refusal within a Member State to relinquish its sovereignty in a specific policy field. The political, institutional and legal solution is treaty opt-out: a protocol attached to the new treaty, giving an exemption from the common policy-field to that Member State at the end of the intergovernmental negotiations. The opt-out protocol enters into force together with the treaty, and is valid for an indeterminate period of time”, Sion 2004. Another example is offered by Denmark: In 1992 this country obtained an opt-out from the single currency, defence and some aspects of Justice and Home Affairs law, then amended by the Lisbon Treaty.31x Ireland is another country involved in some opt-out mechanisms. The Lisbon Treaty “extended the opt-outs of the UK, Ireland and Denmark to include also police and criminal law cooperation, and gave the UK the power to opt-out of pre-existing police and criminal law measures as of 1 December 2014.” S. Peers, ‘Trends in differentiation of EU Law and Lessons for the Future’, Directorate-General for Internal Policies. Policy Department C: Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, 2015, available at: <www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/510007/IPOL_IDA%282015%29510007_EN.pdf>. Partially different is the case of Sweden, which has enjoyed a de facto opt-out since 2003, as Fasone recalls.32x C. Fasone, ‘Il Parlamento europeo nell’Unione asimmetrica’, in A. Manzella & N. Lupo (Eds.), Il sistema parlamentare euro-nazionale, Torino, Giappichelli 2014, pp. 51-98, at 76. Again in the field of the EMU, Article 136 TFEU allows Member States whose currency is the euro “to strengthen the coordination and surveillance of their budgetary discipline”. I will return to this when dealing with the institutional implications of asymmetry in the last part of the article.

Source: F. Tekin, ‘Opt-Outs, Opt-Ins, Opt-Arounds? Eine Analyse der Differenzierungsrealität im Raum der Freiheit, der Sicherheit und des Rechts’, Integration, No. 4, 2012, pp. 237-257 as translated into English by W. Wessels, ‘How to Assess an Institutional Architecture for a Multi-level Parliamentarism in Differentiated Integration?’, 2012 (Directorate General for Internal Policies Policy Department C: Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs), available at: <www.europarl.europa.eu/document/activities/cont/201210/20121003ATT52863/20121003ATT52863EN.pdf>. The opt-out mechanism has been defined as “a form of defection in the EU”.29x M. Sion, ‘The Politics of Opt-Out in the European Union: Voluntary or Involuntary Defection?’, IWM Junior Visiting Fellows’ Conferences, Vol. XVI, No. 7, 2004, available at: <www.iwm.at/wp-content/uploads/jc-16-07.pdf>. An example of an opt-out is the non-participation of the UK in the third stage of economic and monetary union (EMU).30x “Treaty opt-out (as the UK and Danish opt-out of the common currency) occurs when most of the Member States in the EU agree to advance the integration process, and therefore negotiate in an Intergovernmental Conferences (IGC) to change the common EU treaties, but encounter a refusal within a Member State to relinquish its sovereignty in a specific policy field. The political, institutional and legal solution is treaty opt-out: a protocol attached to the new treaty, giving an exemption from the common policy-field to that Member State at the end of the intergovernmental negotiations. The opt-out protocol enters into force together with the treaty, and is valid for an indeterminate period of time”, Sion 2004. Another example is offered by Denmark: In 1992 this country obtained an opt-out from the single currency, defence and some aspects of Justice and Home Affairs law, then amended by the Lisbon Treaty.31x Ireland is another country involved in some opt-out mechanisms. The Lisbon Treaty “extended the opt-outs of the UK, Ireland and Denmark to include also police and criminal law cooperation, and gave the UK the power to opt-out of pre-existing police and criminal law measures as of 1 December 2014.” S. Peers, ‘Trends in differentiation of EU Law and Lessons for the Future’, Directorate-General for Internal Policies. Policy Department C: Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, 2015, available at: <www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/510007/IPOL_IDA%282015%29510007_EN.pdf>. Partially different is the case of Sweden, which has enjoyed a de facto opt-out since 2003, as Fasone recalls.32x C. Fasone, ‘Il Parlamento europeo nell’Unione asimmetrica’, in A. Manzella & N. Lupo (Eds.), Il sistema parlamentare euro-nazionale, Torino, Giappichelli 2014, pp. 51-98, at 76. Again in the field of the EMU, Article 136 TFEU allows Member States whose currency is the euro “to strengthen the coordination and surveillance of their budgetary discipline”. I will return to this when dealing with the institutional implications of asymmetry in the last part of the article.

The example of the Open Method of Coordination (OMC) confirms the role played by asymmetry even at the EU level. Since the complete Europeanization of social policies has been impossible because of the diversity present at the national level the OMC was devised. Indeed, the OMC can be useful in this sense since it “leaves effective policy choices at the national level, but it tries to improve these through promoting common objectives and common indicators and through comparative evaluations of national policy performance”.33x Scharpf 2008.

Enhanced cooperation definitely belongs to the universe of asymmetric options: it aims to ensure, at the same time, unity and diversity. In fact, it allows Member States to experiment with different forms of integration without ‘shutting the door’ to those unwilling to take steps towards deeper integration in specific areas (openness is at the heart of Article 331 TFEU). Enhanced cooperation can be conceived as a sort of extrema ratio to be exploited when the Council realizes that the goals of integration cannot be achieved within a reasonable period by the EU as a whole. The procedures to be followed in this case ensure the intervention and control of the other EU institutions (Commission, Parliament) guaranteeing the common agents’ control.34x See M. Bordignon & S. Brusco, ‘On Enhanced Cooperation’, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 90, No. 10-11, 2006, pp. 2063-2090 and Cantore 2011, p. E-15. After the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty the passerelle mechanism may be applied to enhanced cooperation, with some exceptions represented by the decisions on defence matters or decisions having have military implications.35x Art. 333 TFEU.

Enhanced cooperation under EU law also counterbalances (partly at least)36x Partly because the author mainly refers to the participation of citizens in the public debate. Bauböck’s argument concerning the lack of transparency of asymmetric dynamics, since according to Article 330 TFEU “[a]ll members of the Council may participate in its deliberations”. Finally, enhanced cooperation is conceived for specific areas, and “this a guarantee not only for those Member States without the political will to join enhanced cooperation from the beginning, but also for those which do not meet the objective requirements for joining the enhanced cooperation scheme”.37x Cantore 2011, p. E-16. As mentioned, the discipline of enhanced cooperation under the EU is emblematic of how asymmetry can perform an integrative function. The governing provisions are Articles 330-333 TFEU and Article 20 TEU. As Fabbrini pointed out,38x F. Fabbrini, ‘The Enhanced Cooperation Procedure: A Study in Multispeed integration’, 2012 (Centre for Studies on Federalism Research Paper), available at: <www.csfederalismo.it/it/pubblicazioni/research-paper/835-the-enhanced-cooperation-procedure-a-study-in-multispeed-integration>. all these rules can be traced back to three groups of norms: those concerning the activation (number minimum of member states, role of the Commission, Parliament and Council), those regarding the functioning of enhanced cooperation (regular use of the EU institutions, application of particular rules for the working of Council, use of the passerelle clause) and, finally, those governing the possibility to participate in the cooperation for the ‘non-original parties’). More generally, when analysing these provisions it is possible to infer limits and conditions – what Fabbrini calls both ex ante and ex post caveats39x See also Ibid. – of enhanced cooperation in EU law (for instance, exclusion of areas covered by the EU’s exclusive competence, the necessity to rely on it as a last resort, compliance with the EU Treaties).

All these elements serve as constitutional safeguards since they make the asymmetry produced by enhanced cooperation sustainable under EU law.40x See also Ibid.

A particular form of cooperation is the permanent structured cooperation in the field of common foreign and defence policy involving “those Member States whose military capabilities fulfil higher criteria and which have made more binding commitments to one another in this area with a view to the most demanding missions”,41x Art. 42.6 TEU. On this see M. Cremona, ‘Enhanced Cooperation and the Common Foreign and Security and Defence Policy’, 2009 (EUI Working Paper No. 21/2009), available at: <http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/13002/LAW_2009_21.pdf?sequence=1>. whose conditions are listed in Articles 42.6 and 46 TEU and Protocol 10 to the Lisbon Treaty. It is also possible to recall other forms of differentiation such as those governed by Articles 42 and 45 TEU, again in the field of common security and defence policy, Article 184 TFEU within the implementation of the multiannual framework programme, or Articles 86 and 87 TFEU in the field of judicial cooperation in criminal matters and police cooperation. -

D The New Economic Governance

The use of enhanced cooperation in the field of divorce, patents and financial transaction tax,42x Council Decision of 12 July 2010 (2010/405/EU), OJEU, L 189/12, Council Decision of 10 March 2011 (2011/167/EU), OJEU, L 76/53, Council Decision of 22 January 2013 (2013/52/EU), OJ L 22. on the one hand, and the adoption of the new Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union (TSCG), on the other, have renewed the debate on asymmetry in the life of the Union. When looking at the new economic governance through the perspective of the TSCG, there are two important factors of constitutional mutation: The growing asymmetry of the picture and an increase in intergovernmental dynamics. Fossum has stressed this point by arguing thus:

The crisis has raised serious questions about the assumption that all EU member states will continue to move in the same integrationist direction… One possible outcome of the crisis is that member states may come to occupy permanently different roles and statuses in the EU, a situation that could manifest itself in differentiated authority structures and patterns of decision-making. Thus, rather than seeing further (uniform) integration, the EU may become more differentiated through a combination of differentiated integration and differentiated disintegration43x Fossum 2015, p. 800.

This aspect has been pointed out by Leruth and Lord who wrote “that crisis has changed all this. It is now much harder to assume that differentiated integration may just be ‘noise’ around an underlying trajectory towards more uniform forms of integration”.44x B. Leruth & C. Lord, ‘Differentiated Integration in the European Union: A Concept, a Process, a System or a Theory?’, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2015, pp. 754-763, at 756.

Within the new European economic governance the asymmetric dimension of the EU has been amplified owing to two main factors: First of all, some of the measures mentioned at the beginning have been adopted out of the EU law frame, namely via the conclusion of international agreements. This choice has permitted the creation of a set of rules shared by a group of the EU Member States in the form of a public international law treaty. The second factor is related to the discipline of the enhanced cooperation mechanism in the TSCG. Concerning the first factor, as Bruno de Witte has pointed out, this “turn to international treaties” is not new; even in other cases this path has been followed.45x “In fact, there are numerous earlier examples of international treaties concluded between groups of Member States of the EU. They have concluded, ever since the 1950’s, agreements in areas such as tax law, environmental protection, defence, culture and education”, B. de Witte, ‘Using International Law in the Euro Crisis. Causes and Consequences’ 2013 (ARENA Working Paper No. 4), available at: <www.sv.uio.no/arena/english/research/publications/arena-publications/workingpapers/working-papers2013/wp4-13.pd>.

The first reaction to this trend may be to interpret it as a return to intergovernmentalism and as a loss in terms of supranationalism. But, as Fabbrini has shown, the use of differentiated agreements among members of a union is known even in federal experiences.46x “As the comparative analysis makes clear, also the US Constitution is endowed with an instrument – the ‘compact clause’ – which allows states to pursue flexible and differentiated action within the American Union”, Fabbrini 2012.

Although this is not the first time that international law instruments have been employed to face a supranational issue, scholars do not see a common strategy behind this trend; rather, this path was allegedly chosen because of the flexibility it can offer.47x “Separate international agreements, which do not involve an amendment of the TEU and TFEU, can define alternative requirements for their entry into force. Not only can such agreements be concluded between less than all the EU states, but they can also provide for their entry into force even if not all the signatories are able to ratify. The Fiscal Compact offers a spectacular example of this flexibility in that it provided that the treaty would enter into force if ratified by merely 12 of the 25 signatory states, provided that those 12 are all part of the euro area. The fact that the authors of the Fiscal Compact moved decidedly away from the condition of universal ratification for its entry into force has created a ‘ratification game’ which is very different from that applying to amendment of the European treaties, where the rule of unanimous ratification gives a strong veto position to each individual country,” De Witte 2013. Against this background, the TSCG is peculiar for many reasons, the most evident being the fact that the TSCG intervenes in a situation already dominated by asymmetry, adding another pattern of differentiation. For instance, besides the already existing asymmetry between Euro and non-Euro members, this second group will be differentiated, from now on, between those who signed the new Treaty and those who did not. For instance, building on Rossi’s work,48x L.S. Rossi, ‘Fiscal Compact e conseguenze dell’integrazione differenziata nell’Ue’, in G. Bonvicini & F. Brugnoli (Eds.), Il Fiscal Compact, Roma, Edizioni Nuova Cultura 2012, pp. 29-34. it is possible to argue that the TSCG has created a system characterized by various concentric circles:A first circle is represented by those EU Member States of the Eurozone that have ratified the TSCG (at least “twelve Contracting Parties whose currency is the euro” according to Article 14 TSCG).49x Art. 14, p. 2: “This Treaty shall enter into force on 1 January 2013, provided that twelve Contracting Parties whose currency is the euro have deposited their instrument of ratification, or on the first day of the month following the deposit of the twelfth instrument of ratification by a Contracting Party whose currency is the euro, whichever is the earlier.” The ratification process can be followed at the following link: <www.consilium.europa.eu/en/documents-publications/agreements-conventions/agreement/?aid=2012008>.

A second group is given by those States that do not belong to the Eurozone but that have ratified the TSCG.50x For instance, Poland.

A third circle includes those States that do not participate in the Euro Plus Pact but that have ratified the TSCG.51x For instance, Hungary.

It is clear from this scenario that the TSCG is going to amplify the variable-geometry Union, emphasizing the asymmetric feature of the EU economic governance.

Partially different is the European Stability Mechanism – another international Treaty – that was signed by 19 Member States, i.e. all those States belonging to the Eurozone,52x The Preamble of the ESM Treaty states that: “All Euro area Member States will become ESM Members. As a consequence of joining the Euro area, a Member State of the European Union should become an ESM Member with full rights and obligations, in line with those of the Contracting Parties”. As Bianco pointed out: “It is an obligation that suggests a chronological precedence of the membership in the Eurozone before adhering to the ESM treaty. Art. 2(1) confirms this. Yet, such an obligation would be rather difficult to enforce once the country has already been admitted to the Eurozone. What appears more realistic from a practical point of view is that it is dealt with during the negotiations on the accession to the Euro area of a new country. The latter will be required to commit to ratifying the ESM treaty as a condition to adopt the Euro, albeit the ESM stands outside of the EU legal order. In this regard, the Court of Justice in Pringle maintained that the ESM concerns economic policy and not monetary policy. This is because the Mechanism has the objective of safeguarding financial stability and granting financial assistance, and not of maintaining price stability, setting interest rates or issuing Eurocurrency (which characterize the ECB’s work, and thus monetary policies). Some commentators have noted the ‘legal formalism’ of this reasoning, which fails to recognize that the stability of the Eurozone – the objective of the ESM – is a prerequisite for price stability in that area”. G. Bianco, ‘EU Financial Stability Mechanisms: Few Certainties, Many Lingering Doubts’, European Business Law Review, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2015, pp. 451-471, at 464. but even within them one should distinguish between “those receiving and those granting financial assistance and those which detain the largest share capital of the fund and those that subscribed a minimal share”.53x C. Fasone, ‘Eurozone, Non-Eurozone and “Troubled Asymmetries” Among National Parliaments in the EU. Why and to What Extent this is of Concern’, Perspectives on Federalism, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2015, pp. E-1-E-41, at E-4. In other words, these new economic measures in their entirety has made scholars wonder about the impact of them on the principle of equality of EU Member States.54x Ibid.

Indeed, another source of asymmetry in the new European economic governance is represented by the provisions included in the TSCG and devoted to the enhanced cooperation mechanism, namely Article 10 TSCG. It is possible to express some doubts when comparing the wording of this provision with those of Article 20 of the TEU and Articles 326-334 of TFEU, since Article 20 TEU describes enhanced cooperation as a “last resort”55x Art. 20 para. 2: “The decision authorising enhanced cooperation shall be adopted by the Council as a last resort, when it has established that the objectives of such cooperation cannot be attained within a reasonable period by the Union as a whole, and provided that at least nine Member States participate in it. The Council shall act in accordance with the procedure laid down in Article 329 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union”. ), while outside the EU Treaties enhanced cooperation may be used when “necessary and appropriate”.56x C.M. Cantore & G. Martinico, ‘Asymmetry or Dis-integration? A Few Considerations on the New “Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union”’, European Public Law, Vol. 19, No. 3, 2013, pp. 463-480. It is apposite to have a closer look at Article 10, which reads: “[I]n accordance with the requirements of the European Union Treaties, the Contracting Parties stand ready to make active use, whenever appropriate and necessary, of measures specific to those Member States whose currency is the euro as provided for in Article 136 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and of enhanced cooperation as provided by Article 20 of the Treaty on European Union and Articles 326-334 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union on matters that are essential for the smooth functioning of the euro area, without undermining the internal market”.

My argument is a literal one: the idea is that the TSCG might have introduced a sort of inconsistency or at least an evident textual contradiction between the concept of enhanced cooperation in EU law (Article 20 TEU describes enhanced cooperation as a “last resort”57x Art. 20 para. 2: “The decision authorising enhanced cooperation shall be adopted by the Council as a last resort, when it has established that the objectives of such cooperation cannot be attained within a reasonable period by the Union as a whole, and provided that at least nine Member States participate in it. The Council shall act in accordance with the procedure laid down in Article 329 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union”. ) and enhanced cooperation outside the EU Treaties where, as we saw, this mechanism may be used when ‘necessary and appropriate’, in spite of the renvoi to Article 20 TEU made in Article 10 TSCG.

These formulas employed by the TSCG seem to introduce an element of discretion that is very far from the idea of extrema ratio and might open the door to a greater leeway to the States in the use of this mechanism. What about the consequences of this inconsistency? Is it possible to solve the antinomy by means of interpretation? Although difficult to say, in my view the systematic reading of these two provisions might lead to a relativization of the very idea of last resort, which is already, per se, an ambiguous concept. This could induce a distortion of the ratio of enhanced cooperation even in EU law.58x An example of this ambiguity is given by the reading given to this concept in the recent opinion on the case concerning the enhanced cooperation scheme in the field of a unitary patent given by AG Bot. On that occasion, AG Bot emphasized the ambiguity of the idea of ‘last resort’ and concluded by saying that: “…[C]ooperation must come into play as a last resort, when it is established that the objectives pursued by that cooperation cannot be attained within a reasonable period by the Union as a whole”. As said, AG Bot reads this safeguard mainly as an issue of time. The opinion of Advocate General Bot, joined cases C-274/11 and C-295/11, Kingdom of Spain and Italian Republic v. Council of the European Union, 11 December 2012 (especially see para. 108). I indeed agree with Fabbrini when he argues that: “enhanced cooperation can be used only when EU member states disagree on whether to act jointly at the EU level. On the contrary, the procedure cannot be used when member states agree on the opportunity of expanding integration into a new legal field but disagree on how to act at the EU level. While it will be argued that this interpretation restricts the possible room for resort to enhanced cooperation, the paper explains that this construction has several advantages, including preserving the integrity of the EU constitutional order, preventing circumvention of Treaty rules and providing the EU judiciary with a manageable standard to review action by the EU political branches”, Fabbrini 2012. In its subsequent decision the CJEU rejected the plea in law alleging breach of the condition of the last resort, and the actions by the Kingdom of Spain and the Italian Republic were dismissed (CJEU, Joined Cases C-274/11 and C-295/11, available at: <www.curia.europea.eu>). The wording of Article 10 TSCG seems to show the hybrid nature of the Treaty itself. Even though it is an international agreement outside the scope of the EU Treaties, it is not completely outside the scope of the EU framework, as it aims to benefit from EU institutions and EU law features.

It can be said – and, perhaps, this was the intention of the drafters – that Article 10 TSCG might be, in principle, the pathway for the ‘communitarization’ of the TSCG through enhanced cooperation schemes. On the other hand, this was already an option before the conclusion of the TSCG, but it was not exploited by the EU Member States at that time.

There is another reason for which the text of Article 10 is at odds with its correspondent provisions included in the fundamental EU Treaties: Article 10 TSCG only states that enhanced cooperation might not undermine internal markets, but internal market is just one of the elements included in Article 326 TFEU.59x Art. 326 TFEU: “Any enhanced cooperation shall comply with the Treaties and Union law. Such cooperation shall not undermine the internal market or economic, social and territorial cohesion. It shall not constitute a barrier to or discrimination in trade between Member States, nor shall it distort competition between them”.

One could say that Article 10 in any case refers to all the relevant norms disciplining the phenomenon in EU law and this is true, but why recall in an expressed manner just one of these elements? I see two possible interpretations here: the last lines of Article 10 could be either pleonastic (by expressing just one of the elements recalled by the relevant EU Treaties provisions) or ‘selective’, willing to give a particular value just to one of the elements recalled by the EU Treaties and thus creating something different. This problematic picture is made even more complicated by the uncertain mandate of the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) (as we saw, it is not clear from Article 8 TSCG whether the task of the Court concerns the content of Article 3 only or all the contents of the TSCG, and this, of course, matters),60x On this see V.F. Comella, ‘Amending the National Constitutions to Save the Euro: Is This the Right Strategy?’, Texas International Law Journal, Vol. 43, No. 2, 2013, pp. 223-240, at 236. i.e. one of the most important actors in the process of EU integration, the guardian of those constitutional safeguards that inspire the life of the Union.

As previously stated, one of the causes of the increased asymmetry of the new European economic governance is given by the use of public international law instruments, and this leads me to the other important factors of constitutional mutation introduced by the last legal developments. It concerns the EU’s methodology of action or, in other words, the choice of the legal sources used to deal with the crisis. This has been clearly articulated by Chiti and Texeira61x E. Chiti & P.G. Teixeira, ‘The Constitutional Implications of the European Responses to the Financial and Public Debt Crisis’, Common Market Law Review, Vol. 50, No. 3, 2013, pp. 683-708. : according to them, when reacting to the crisis the EU has been progressively abandoning the Union method, minimizing the role of the “Community channels” reinforcing the “intergovernmental instruments”.62x Ibid. This has created a partial development of this discipline outside the EU Treaties, which has resulted in a mix of EU legal acts and international Treaties with consequent issues in terms of consistency of some of the solutions adopted in this phase with EU law.63x G. Bianco, ‘The New Financial Stability Mechanisms and Their (Poor) Consistency with EU Law’, 2012, EUI RSCAS 2012/44, available at: <http://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/23428>. For all these reasons the debt and financial crisis would have triggered a dangerous process of transformation with a “departure from the traditional paradigm of the EU economic constitution”64x Chiti & Teixeira 2013, p. 700. and the exhaustion of “the main democratic legitimacy sources of the EU polity”.65x Ibid., p. 706. Indeed, many other authors have argued that the latest developments affect the legitimacy and democracy of the European project and represent a fracture in the history of its economic constitution66x See also C. Joerges, ‘Europe’s Economic Constitution in Crisis and the Emergence of a New Constitutional Constellation’, 2012 (Zentra Working Papers in Transnational Studies No. 06/2012), available at: <http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2179595>. and, more in general, a change in its constitutional paradigm: this is the point made by Dawson and de Witte, for instance, who argued that the anti-crisis measures have “altered the constitutional balance upon which the Union’s stability is premised”,67x M. Dawson & F. de Witte, ‘Constitutional Balance in the EU after the Euro-Crisis’, Modern Law Review, Vol. 76, No. 5, 2013, pp. 817-844. This idea of constitutional balance is based on three components, namely the substantive, institutional and spatial dimensions; all these three would be affected by the recent evolution of the anti-crisis discipline: “The response to the euro-crisis destabilises the Union’s substantive balance by circumventing its limited mandate in redistributive policies, which was meant to ensure that citizens have ownership and authorship over the core values that shape their society (the second section). It equally recalibrates the institutional balance by decreasing the voice of marginalised interests and representative institutions. This loss of representative influence is likely to result in greater power for national executives, with responsibilities for the initiation of, and compliance with, policy proposals shifting during the crisis towards the European Council (in the third section). Finally…the Union’s response to the euro-crisis also threatens the spatial balance of the Union, which protects the voice of smaller and poorer Member States and their citizens from majoritarian or even hegemonic tendencies. The increased influence of the bigger, more resourceful Member States, in combination with the changes to the Union’s substantive and institutional structure, leads to the loss of political autonomy for smaller and poorer Member States” (Dawson & de Witte 2013, pp. 817-818). its commitment to pluralism and shows its inability to “accommodate the plurality of interests that distributive conflicts engender”.68x Dawson & de Witte 2013, p. 822. -

E The Institutional Impact of Asymmetry in the Current Phase of the European Integration

What is the institutional impact of these forms of asymmetry?69x On this topic see Fasone 2014, p. 73 et seq. The answer depends on the specific mechanism and the EU institution taken into account. When dealing with enhanced cooperation, for instance, Article 330 TFEU expressly makes a distinction by stating that “[a]ll members of the Council may participate in its deliberations, but only members of the Council representing the Member States participating in enhanced cooperation shall take part in the vote. Unanimity shall be constituted by the votes of the representatives of the participating Member States only”. Another important set of provisions is represented by Protocol No. 14 on the “Euro-Group” annexed to the Lisbon Treaty, which provides for some meetings among the ministers of the Member States whose currency is the euro “to discuss questions related to the specific responsibilities they share with regard to the single currency. The Commission shall take part in the meetings. The European Central Bank shall be invited to take part in such meetings, which shall be prepared by the representatives of the Ministers with responsibility for finance of the Member States whose currency is the euro and of the Commission” (Article 1). Article 2 of this Protocol also states that “Ministers of the Member States whose currency is the euro shall elect a president for two and a half years, by a majority of those Member States”. Since the TSCG applies to Euro and non-Euro countries, its Article 12 of the TSCG70x Art. 12 of the TSCG “1. The Heads of State or Government of the Contracting Parties whose currency is the euro shall meet informally in Euro Summit meetings, together with the President of the European Commission. The President of the European Central Bank shall be invited to take part in such meetings. The President of the Euro Summit shall be appointed by the Heads of State or Government of the Contracting Parties whose currency is the euro by simple majority at the same time as the European Council elects its President and for the same term of office.

2. Euro Summit meetings shall take place when necessary, and at least twice a year, to discuss questions relating to the specific responsibilities which the Contracting Parties whose currency is the euro share with regard to the single currency, other issues concerning the governance of the euro area and the rules that apply to it, and strategic orientations for the conduct of economic policies to increase convergence in the euro area”. distinguishes between Contracting Parties whose currency is the Euro and the other Contracting Parties.71x Art. 12 of the TSCG “3. The Heads of State or Government of the Contracting Parties other than those whose currency is the euro, which have ratified this Treaty, shall participate in discussions of Euro Summit meetings concerning competitiveness for the Contracting Parties, the modification of the global architecture of the euro area and the fundamental rules that will apply to it in the future, as well as, when appropriate and at least once a year, in discussions on specific issues of implementation of this Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union.

[…] 6. The President of the Euro Summit shall keep the Contracting Parties other than those whose currency is the euro and the other Member States of the European Union closely informed of the preparation and outcome of the Euro Summit meetings.”

Another interesting provision is embodied in Article 13 of the TSCG, which should be part of a broader trend fed by Protocol 172x Protocol on the Role of National Parliaments in the European Union. to the Lisbon Treaty, whose Articles 9 and 1073x Art. 9: “The European Parliament and national Parliaments shall together determine the organisation and promotion of effective and regular interparliamentary cooperation within the Union”.

Art. 10: “A conference of Parliamentary Committees for the Affairs of the Union may submit any contribution it deems appropriate for the attention of the European Parliament, the Council and the Commission. That conference shall in addition promote the exchange of information and best practice between national Parliaments and the European Parliament, including their special committees. It may also organize interparliamentary conferences on specific topics, in particular to debate matters of common foreign and security policy, including common security and defence policy. Contributions from the conference shall not bind national Parliaments and shall not prejudge their positions”. are devoted to inter-parliamentary cooperation. More generally, today inter-parliamentary cooperation in the EU develops through different channels (Conference of Community and European Affairs committees of parliaments of the European Union – COSAC; Joint Parliamentary Meetings, Joint Committee Meetings, Meetings of Sectoral Committees, etc.), but it is sufficient to refer to recent works here without going into detail.74x C. Fasone, ‘Interparliamentary Cooperation and Democratic Representation in the European Union’, in S. Kröger & D. Friedrich (Eds.), The Challenge of Democratic Representation in the European Union, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan 2011, pp. 41-58.

More recently, new arenas of “second generation”75x D. Fromage, ‘Parlamento Europeo y Parlamentosnacionales después del Tratado de Lisboa y en un contexto de crisis: ¿Un acercamiento de grado diverso según el ámbito?’, in P. Andrés & J.I. Ugartemendia (Eds.), El Parlamento europeo: ¿esta vez es diferente?, Bilbao, IVAP, forthcoming (on file with author). have been created: the Inter-parliamentary Conference for the Common Foreign and Security Policy and the Common Security and Defence Policy (CFSP/CSDP),76x Decisions of the Conference of Speakers of the European Union (EU) Parliaments at its meetings in Brussels, on 4-5 April 2011, and in Warsaw, on 20-21 April 2012, establishing an Inter Parliamentary Conference for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), <www.europarl.europa.eu/webnp/cms/pid/1932>. which gathers delegations of the national Parliaments of the EU member states and the European Parliament.77x J. Wouters & K. Raube, ‘Europe’s Common Security and Defence Policy: The Case for Inter-Parliamentary Scrutiny’, 2012 (Leuven Centre for Global Governance Studies Working Paper), available at: <https://ghum.kuleuven.be/ggs/publications/working_papers/new_series/wp81-90/wp90.pdf>.

Article 13 of the TSCG reads: “[T]he European Parliament and the national Parliaments of the Contracting Parties will together determine the organization and promotion of a conference of representatives of the relevant committees of the European Parliament and representatives of the relevant committees of national Parliaments in order to discuss budgetary policies and other issues covered by this Treaty”.

The nature and functions of this conference have been discussed after the entry into force of the TSCG and only partly clarified after a meeting of the Speakers of Parliament of the Founding Member States of the European Union and the European Parliament held in Luxembourg on 11 January 2013. Actually, that meeting was characterized by the emergence of different views concerning the role of the inter-parliamentary cooperation in the EU. On that occasion a working paper was discussed in which it was stated that “this conference would discuss topical issues of Economic and Monetary Union, including agreements in the framework of the European Semester, in order to reinforce dialogue between the national Parliaments and with the European Parliament. Yet binding decisions could only be taken at the responsible level”. Moreover, it was added that “[t]he Conference will meet at least twice a year, notably before the European Council in June, before or after the adoption of the relevant documents, namely the recommendations on the stability and reform programmes, the orientation of economic policies, the Growth Survey and the Alert Mechanism Report”.78x Working paper of the meeting of the Speakers of Parliament of the Founding Member States of the European Union and the European Parliament in Luxembourg on 11 January 2013, available at: <www.eerstekamer.nl/eu/documenteu/_working_paper_of_the_meeting_of/f=/vj6hl2jhabhi.pdf. At the beginning it was not clear whether the delegations of the UK, the Czech Republic and Croatia (countries that have not signed the TSCG) were part of this conference, but then an agreement was found in this sense79x Compare this Conference with the so-called Arthuis Report. J. Arthuis, ‘L’Avenir de la Zone Euro: l’integration politique ou le chaos’, 2012, available at: <www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/var/storage/rapports-publics/124000129/0000.pdf>. at the Conference of Speakers of EU Parliaments held in Nicosia on 21-23 April 2013.80x The Presidency Conclusions of the Conference of Speakers of EU Parliaments held in Nicosia, 21-23 April 2013, can be found here: <www.senate.be/event/20130422-Nicosia/Conclusions_Speakers_ConferenceEN_24-4-2013.pdf>. Another potential form of institutional asymmetry could be represented by a unified Eurozone external representation in international organizations like the International Monetary Fund. As Koedooder recalled,81x C. Koedooder, ‘Will the Juncker Commission Initiate Unified Eurozone External Representation?’, European Law Blog, 13 November 2014, available at: <http://europeanlawblog.eu/?p=2592>. from a legal point of view Article 138.2 TFEU – applicable to Eurozone Member States only – reads: “[t]he Council, on a proposal from the Commission, may adopt appropriate measures to ensure unified representation within the international financial institutions and conferences. The Council shall act after consulting the European Central Bank”. However, the legal picture is more complicated under EU law, as Koedooder suggests, and another issue is represented by a possible IMF membership, since according to Article II, Section 2 of the IMF Articles of Agreement, the IMF82x ‘Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund’, available at: <www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/aa/>. accepts – as members – only ‘countries’ and an amendment of this provision has been suggested in this sense.83x Koedooder 2014.

Another form of institutional asymmetry identified by scholars is that concerning the equality of national parliaments and leading to “an unequal distribution of powers amongst these legislatures, due to a peculiar combination of international, EU and national law”.84x Fasone 2015, p. 34.

Fasone identifies three cases of asymmetry concerning national parliaments: the first one concerns those parliaments “able to block or veto the adoption and implementation of Euro crisis measures even though their Member State is not bound by them”,85x Ibid. and the example is given by the participation of non-Eurozone parliaments in the amendment procedure followed to change Article 136 TFEU. The second case refers to “the power of some national parliaments, and first of all of the German Bundestag, to block the functioning of collective mechanisms, like the ESM, as a consequence of constitutional case law, constitutional rules and national legislation”,86x Ibid. and it is evidence of the great variety of parliamentary powers at the national level. Finally, Fasone mentions the case of those parliaments of “countries subject to strict conditionality”.87x Ibid.

These are just examples, but as I wrote at the beginning of this section, it is not easy to find a univocal trend towards an institutional differentiation as a product of the increased asymmetry in the EU, and it is sufficient to have a look at the role of the European Parliament to have a confirmation of this. As, once again, Fasone pointed out, the European Parliament “has traditionally been indifferent towards differentiated integration”,88x Ibid., p. 80. although a debate concerning the possibility of a differentiated representation has been discussed hugely.89x On this see ibid., 2014, p. 80. The European Parliament itself dealt with the issues sometimes: for instance, in a Resolution dated 2013,90x Resolution of the European Parliament of 12 December 2013 on the constitutional problems of multi-tier governance in the European Union, A7-0372/2013. it stated that “any formal differentiation of parliamentary participation rights with regard to the origin of Members of the European Parliament represents discrimination on grounds of nationality, the prohibition of which is a founding principle of the European Union, and violates the principle of equality of Union citizens as enshrined in Article 9 TEU”.91x Ibid., para. 29. This point seems to be too univocal to leave margins open for a change in the near future at least. Moreover, it is not yet clear whether such a differentiation should be limited to the activities connected to the new economic governance or extended to all the cases of multi-speed Europe.92x Fasone 2014, p. 80. -

F Final Remarks

This article tried to offer a reflection on asymmetry as an instrument of differentiated integration in the current phase of the EU integration process. In order to do so I structured the article in four parts: after having clarified what I mean by asymmetry as an instrument of integration, I looked at EU law, recalling the most important features of asymmetry in that context. In a third part I explored the implications of the financial crisis, which has increased the resort to asymmetric instruments, paying particular attention to enhanced cooperation and expressing some concerns about Article 10 TSCG. However, as written, Article 10 could represent the pathway to ‘communitarization’ of the TSCG suggested by Article 16 of the TSCG.93x “Within five years, at most, of the date of entry into force of this Treaty, on the basis of an assessment of the experience with its implementation, the necessary steps shall be taken, in accordance with the Treaty on the European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, with the aim of incorporating the substance of this Treaty into the legal framework of the European Union”.

In the last part of the article, I dealt with some recent proposals concerning the differentiated representation of the Eurozone. When jumping from procedures to institutions, as I tried to make clear when recalling the main scholarly views on that, there is no univocal trend or solution. The question of whether the EU should give institutional form to these asymmetric forces depends on the particular asymmetric instrument taken into account and on the specific EU institution we have in mind. As we saw, 330 TFEU already provides for special procedures for the functioning of the Council in the field of enhanced cooperation (based on the distinction between participation in the deliberation and participation in the vote), while the European Parliament has so far been traditionally clear in refusing the possibility of an asymmetric representation that could jeopardize the principle enshrined in Article 9 TEU.

Reasoning in terms of a European Parliament à la carte and making an interesting parallelism with the West Lothian question in the UK,94x Named after Tam Dalyell, MP for West Lothian, who raised the question of the participation of MPs in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in the UK Parliament after devolution. In a debate on devolution to Scotland and Wales on 14 November 1977, Mr Dalyell said: “For how long will English constituencies and English Honourable members tolerate at least 119 Honourable Members from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland exercising an important, and probably often decisive, effect on British politics while they themselves have no say in the same matters in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland”, Entry “West Lothian question”, in Glossary, available at: <www.parliament.uk/site-information/glossary/west-lothian-question/>. scholars have identified several options of differentiation; among them one could recall those of (1) a differentiated representation according to the rights of members of the European Parliament by limiting the exercise of the right to vote according to a ratione materiae criterion or by attributing a right to vote to the national delegations95x Fasone 2014, p. 86. ; (2) a differentiation within the committee system with the creation of a subcommittee for the Eurozone (but in this case what should its relationship be with the standing committee on economic and monetary affairs – ECON); (3) a new parliamentary Chamber for the Eurozone96x See the aforementioned Arthuis Report. Arthuis 2012. ; (4) a Conference of Eurozone national parliaments (but this could perhaps jeopardize the role of the European Parliament in this field)97x Fasone 2014, p. 95 et seq. ; (5) a Eurozone Parliament composed of members of the European Parliament elected in Eurozone Countries or a third Chamber of Eurozone national parliaments, perhaps with a veto power on matters decided by the Euro-Group, Commission or Euro Summit98x Ibid., p. 85 et seq. See also L. Tsoukalis, The Unhappy State of the Union. Europe Needs a New Grand Bargain, London, Policy Network 2014, p. 77, available at: <www.policy-network.net/publications_download.aspx?ID=8834>. ; (6) a directly elected Eurozone Parliament recently proposed, among others, by Piketty99x T. Piketty, ‘Il faut donner un parlement à l’euro’, Le Monde, 20 May 2014, available at: <www.lemonde.fr/europeennes-2014/article/2014/05/20/thomas-piketty-la-democratie-contre-les-marches_4421986_4350146.html>. but that would perhaps result in increasing the complex architecture in this ambit.100x Fasone 2014, pp. 96-97.

These issues are still debated: scholars have identified different solutions, for some of them a Treaty revision seems to be unavoidable, and this makes this discussion even more technical and complicated; moreover, the principle stated in Article 9 TEU could hardly be circumnavigated.

Indeed, this discussion leads us to a more general problem; in other words, the answer to the question of what kind of institutions we want is inevitably connected to the idea of integration we might have in mind and unveils the hard choice to be made between institutional inclusiveness and flexible procedures, the real constitutional dilemma of the EU nowadays. -

1 As Fossum pointed out, differentiation and differentiated integration are not synonymous: “These developments suggest a need to distinguish differentiation from differentiated integration. We might understand differentiation as a wider concept that includes, yet goes beyond, differentiated integration. In other words, it encompasses traditional understandings of differentiated integration as mainly consisting of the same integration only at different speeds. Yet it also includes two new differences between member states that are likely to be wider and more lasting: first, cases where some states integrate more closely whilst, at the same time and for connected reasons, others disintegrate from their previous levels of involvement with the Union; and second, cases where even notionally full members come to be regarded as having different membership status”. J.E. Fossum, ‘Democracy and Differentiation in Europe’, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2015, pp. 799-815, at 800.

-

2 D. Leuffen, B. Rittberger & F. Schimmelfennig, Differentiated Integration. Explaining Variation in the European Union, Basingstoke, Palgrave 2013.

-

3 F. Schimmelfennig, D. Leuffen & B. Rittberger, ‘The European Union as a System of Differentiated Integration: Interdependence, Politicization and Differentiation’, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2015, pp. 764-782: “We distinguish two types of differentiation that we term vertical and horizontal differentiation. Vertical differentiation means that policy areas have been integrated at different speeds and reached different levels of centralization over time. Horizontal differentiation relates to the territorial dimension and refers to the fact that many integrated policies are neither uniformly nor exclusively valid in the EU’s member states. Whereas many member states do not participate in all EU policies (internal horizontal differentiation), some non-members participate in selected EU policies (external horizontal differentiation)”.

-

4 Leuffen 2013, p. 10.

-

5 A. Warleigh-Lack, ‘Differentiated Integration in the European Union: Towards a Comparative Regionalism Perspective’, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2015, pp. 871-887.

-

6 As Lord recalls, see C. Lord, ‘Utopia or Dystopia? Towards a Normative Analysis of Differentiated Integration’, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2015, pp. 783-798; and “differentiated integration has been transformed from taboo to one of the main sources of pragmatic compromise in EU politics”; see also R. Adler-Nissen, ‘Opting Out of an Ever Closer Union: The Integration Doxa and the Management of Sovereignty’, West European Politics, Vol. 34, No. 5, 2011, pp. 1092-1113.

-

7 A.C.-G. Stubb, ‘A Categorisation of Differentiated Integration’, Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 34, No. 2, 1996, pp. 283-295; Warleigh-Lack 2015, p. 876.

-

8 H. Kelsen, General Theory of Law and State, New York, Russell and Russell 1945, pp. 115-122; H. Kelsen, The Pure Theory of Law, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press 1970, pp. 208-214.

-

9 F. Palermo, ‘Divided We Stand. L’asimmetria negli ordinamenti composti’, in A. Torre et al. (Eds.), Processi di devolution e transizioni costituzionali negli Stati unitari (dal Regno Unito all’Europa), Torino, Giappichelli 2007, pp. 149-170; R.L. Watts, A Comparative Perspective on Asymmetry in Federations, 2005 (Asymmetry Series IIGR, Queen’s University), available at: <www.iigr.ca/pdf/publications/359_A_Comparative_Perspectiv.pdf>.

-

10 Watts 2005.

-

11 The word asymmetry has acquired a variety of meanings: when talking about asymmetries one can distinguish between financial and constitutional asymmetry, or between de jure and de facto asymmetry. De jure asymmetry “refers to asymmetry embedded in constitutional and legal processes, where constituent units are treated differently under the law. The latter, de facto asymmetry, refers to the actual practices or relationships arising from the impact of cultural, social and economic differences among constituent units within a federation, and, as Tarlton noted, is typical of relations within virtually all federations” (Watts 2005).

-

12 C.D. Tarlton, ‘Symmetry and Asymmetry as Elements of Federalism: A Theoretical Speculation’, Journal of Politics, Vol. 27, No. 4, 1965, pp. 861-874.

-

13 Ibid., p. 861.

-

14 Ibid.

-

15 Ibid., p. 874.

-

16 M. Burgess, ‘Federalism and Federation: A Reappraisal’, in M. Burgess & A.G. Gagnon (Eds.), Comparative Federalism and Federation, Toronto, Toronto University Press 1993, pp. 3-14; M. Burgess & F. Gresse, ‘Symmetry and Asymmetry Revisited’, in R. Agranoff (Ed.), Accommodating Diversity: Asymmetry in Federal States, Baden-Baden, Nomos Verlag 1999, pp. 43-56.

-

17 R. Bauböck, ‘United in Misunderstanding? Asymmetry in Multinational Federations’, 2001 (ICE Working Paper series), available at: <http://eif.univie.ac.at/downloads/workingpapers/IWE-Papers/WP26.pdf>.

-

18 Ibid.

-

19 “Highly asymmetric federations become opaque for their citizens”, Bauböck 2001.

-

20 Bauböck 2001.

-

21 F. Palermo, ‘La coincidenza degli opposti: l’ordinamento tedesco e il federalismo asimmetrico?’, 2007, available at: <www.federalismi.it/nv14/articolo-documento.cfm?artid=6991>.

-

22 See, for instance, the examples of differentiated integration treated by F. Tekin, ‘Opt-Outs, Opt-Ins, Opt-Arounds? Eine Analyse der Differenzierungsrealität im Raum der Freiheit, der Sicherheit und des Rechts’, Integration, No. 4, 2012, pp. 237-257 as translated into English by W. Wessels, ‘How to Assess an Institutional Architecture for a Multi-level Parliamentarism in Differentiated Integration?’, 2012 (Directorate General for Internal Policies Policy Department C: Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs), available at: <www.europarl.europa.eu/document/activities/cont/201210/20121003ATT52863/20121003ATT52863EN.pdf>.

-

23 M. Avbelj, ‘Differentiated Integration – Farewell to the EU-27?’, German Law Journal, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 191-212, at 193-194.

-

24 J.-C. Piris, ‘It Is Time for the Euro Area to Develop Further Closer Cooperation Among Its Members’, 2011 (Jean Monnet Working Paper 5/2011), available at: <http://centers.law.nyu.edu/jeanmonnet/papers/11/110501.html>.

-

25 Watts, for instance, mentions the EU in his writings on asymmetry: R.L. Watts, ‘The Theoretical and Practical Implications of Asymmetrical Federalism’, in R. Agranoff (Ed.), Accommodating Diversity: Asymmetry in Federal States, Baden-Baden, Nomos Verlag 1999, pp. 24-35, at 29.

-

26 L. Miles, ‘Introduction: Euro Outsiders and the Politics of Asymmetry’, Journal of European Integration, Vol. 17, No. 3, 2005, pp. 3-23.

-

27 F. Scharpf, ‘The European Social Model: Coping with the Challenges of Diversity’, 2008 (MPIfG Working Paper 02/8), available at: <http://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/mpifgw/028.html>. See also M. Dawson, ‘Three Waves of New Governance in the European Union’, European Law Review, Vol. 36, No. 2, 2011, pp. 208-226.

-

28 J.M. Beneyto & J.M. González-Orús (Eds.), Unity and Flexibility in the Future of the European Union: The Challenge of Enhanced Cooperation, Madrid, CEU–S. Pablo 2009, available at: <www.ceuediciones.es/documents/ebookceuediciones1.pdf> and C.M. Cantore, ‘We’re One, but We’re Not the Same: Enhanced Cooperation and the Tension Between Unity and Asymmetry in the EU’, Perspectives on Federalism, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2011, pp. E-1-E-21. See in general, G. de Búrca & J. Scott (Eds.), Constitutional Change in the European Union, Oxford, Hart Publisher 2000.

-

29 M. Sion, ‘The Politics of Opt-Out in the European Union: Voluntary or Involuntary Defection?’, IWM Junior Visiting Fellows’ Conferences, Vol. XVI, No. 7, 2004, available at: <www.iwm.at/wp-content/uploads/jc-16-07.pdf>.

-

30 “Treaty opt-out (as the UK and Danish opt-out of the common currency) occurs when most of the Member States in the EU agree to advance the integration process, and therefore negotiate in an Intergovernmental Conferences (IGC) to change the common EU treaties, but encounter a refusal within a Member State to relinquish its sovereignty in a specific policy field. The political, institutional and legal solution is treaty opt-out: a protocol attached to the new treaty, giving an exemption from the common policy-field to that Member State at the end of the intergovernmental negotiations. The opt-out protocol enters into force together with the treaty, and is valid for an indeterminate period of time”, Sion 2004.

-

31 Ireland is another country involved in some opt-out mechanisms. The Lisbon Treaty “extended the opt-outs of the UK, Ireland and Denmark to include also police and criminal law cooperation, and gave the UK the power to opt-out of pre-existing police and criminal law measures as of 1 December 2014.” S. Peers, ‘Trends in differentiation of EU Law and Lessons for the Future’, Directorate-General for Internal Policies. Policy Department C: Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, 2015, available at: <www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/510007/IPOL_IDA%282015%29510007_EN.pdf>.

-

32 C. Fasone, ‘Il Parlamento europeo nell’Unione asimmetrica’, in A. Manzella & N. Lupo (Eds.), Il sistema parlamentare euro-nazionale, Torino, Giappichelli 2014, pp. 51-98, at 76.

-

33 Scharpf 2008.

-

34 See M. Bordignon & S. Brusco, ‘On Enhanced Cooperation’, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 90, No. 10-11, 2006, pp. 2063-2090 and Cantore 2011, p. E-15.

-

35 Art. 333 TFEU.

-

36 Partly because the author mainly refers to the participation of citizens in the public debate.

-

37 Cantore 2011, p. E-16.

-

38 F. Fabbrini, ‘The Enhanced Cooperation Procedure: A Study in Multispeed integration’, 2012 (Centre for Studies on Federalism Research Paper), available at: <www.csfederalismo.it/it/pubblicazioni/research-paper/835-the-enhanced-cooperation-procedure-a-study-in-multispeed-integration>.

-

39 See also Ibid.

-

40 See also Ibid.

-

41 Art. 42.6 TEU. On this see M. Cremona, ‘Enhanced Cooperation and the Common Foreign and Security and Defence Policy’, 2009 (EUI Working Paper No. 21/2009), available at: <http://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/13002/LAW_2009_21.pdf?sequence=1>.

-

42 Council Decision of 12 July 2010 (2010/405/EU), OJEU, L 189/12, Council Decision of 10 March 2011 (2011/167/EU), OJEU, L 76/53, Council Decision of 22 January 2013 (2013/52/EU), OJ L 22.

-

43 Fossum 2015, p. 800.

-

44 B. Leruth & C. Lord, ‘Differentiated Integration in the European Union: A Concept, a Process, a System or a Theory?’, Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 22, No. 6, 2015, pp. 754-763, at 756.

-