-

A. Introduction

How does law develop in common law jurisdictions? The question necessarily calls for a comparative analysis. Indeed, it is remarkable how much variation can be found in diverse common law jurisdictions. In part, this can be put down to broader social and cultural factors. There has been much discussion of the social and cultural differences between common law and civil law jurisdictions,1x See, for a summary, B. Markesinis, Comparative Law in the Courtroom and the Classroom: The Story of the Last Thirty-Five Years, Hart Publishing, Oxford, 2003. and between the developed and the developing world,2x And see R. Michaels, ‘The Second Wave of Comparative Law and Economics?’, 59 University of Toronto Law Journal 2009, p. 197, at pp. 200-201 especially. noting the ways these may impact on legal process. But social and cultural diversity can be found across the common law world, including parts that on the surface may seem broadly similar: England, Australia and New Zealand, for instance.3x See, for instance, as to New Zealand and Australia, A. Grimes, L. Wevers & G. Sillivan (Eds.), States of Mind: Australia and New Zealand 1901-2001, Institute of Policy Studies, Wellington, 2002. And, as Kahn-Freund says, a lawyer who seeks to understand the legal process as a process of policy making cannot hope to do so “without knowing something about the needs of the society which the law seeks to satisfy”.4x O. Kahn-Freund, Comparative Law as an Academic Subject, Inaugural Lecture delivered at the University of Oxford, 12 May 1965, Clarendon Press, Oxford, p. 8.

The institutional arrangements for law reform may also make a difference. Some operate from outside the jurisdiction, as in England (and more generally the UK) where much law reform affecting domestic law is now dictated to an extent by European institutions. But others are purely domestic, and these may be equally, if not more, influential. National legislative bodies are obvious examples. But the presence or absence of a law reform commission or other law reform body may also have significant implications for the development of legislation, as noted inter alia by Bennett Moses and Ricketson.5x L. Bennett Moses, ‘Agents of Change: How the Law “Copes” With Technological Change’, 20 Griffith Law Review 2011, p. 763; S. Ricketson, ‘The Future of Australian Intellectual Property Law Reform and Administration’, 3 Australian Intellectual Property Journal 1992, p. 1. Additionally, as Bennett Moses points out, law reform is not just concerned with legislation: for instance, courts may engage in law reform.6x L. Bennett Moses, ‘Adapting the Law to Technological Change: A Comparison of Common Law and Legislation’, 2003 University of New South Wales Law Journal, p. 394. And Kahn-Freund has gone further, stating that firm distinctions cannot be drawn between ‘litigation’ and ‘legislation’ and that “living law is capable of developing hybrid patterns”.7x O. Kahn-Freund, ‘Legislation Through Adjudication: The Legal Aspects of Fair Wages Clauses and Recognised Conditions’, 11 Modern Law Review 1948, p. 269, at p. 270.

More generally, we need to pay attention to the values and practices of those who engage in law reform. As Ricketson observes, when it comes to legislation, there may be distinct cultures of law reform (even in jurisdictions that may be similar in other respects).8x Ricketson, 1992, noting especially that New Zealand’s historical record on intellectual property law reform has often historically been more nimble and experimental than that of Australia. And see also, S. Frankel & M. Richardson, ‘Limits of Free Trade Agreements: The New Zealand/Australia Experience’, in C. Antons & R. Hilty (Eds.), Intellectual Property Aspects of Free Trade Agreements in the Asia-Pacific Region, Kluwer Law International, Alphen aan den Rijn, forthcoming 2013 (New Zealand more intent on determining the ‘best model’). Further, as to courts, most common law jurisdictions can still be characterized as quite formalist and precedent-bound, although the United States is clearly exceptional in the way that judges pay explicit regard to social policy. Here we can see the on-going influence of the American Legal Realist movement of the 20th century. As noted by Fisher et al., “Legal Realism has had a substantial impact on American judges’ understandings of their responsibilities and power.”9x W. Fisher, M. Horwitz & T. Reed (Eds.), American Legal Realism, Oxford University Press, New York, p. xv. But even when it comes to the so-called formalist jurisdictions, judgments may also be infused with policy and ideas about reform albeit their influence may be more implicit and less elaborated than in judgments in the United States.10x Of course in traditional formalist terms judges do not function as legislators – and see Bennett Moses, 2003, at 406, citing Gaudron and McHugh JJ in Breen v. Williams, 186 CLR 71, 115 (1996). But even the High Court has hinted at its ability to create new law in exceptional circumstances (while continuing to express a preference for incrementalism); see, e.g., Australian Broadcasting Corporation v. Lenah Game Meats Pty Ltd., 208 CLR 199 (2001), Gummow and Hayne JJ at [132]. As Tamanaha says,11x B. Tamanaha, Beyond the Formalist-Realist Divide: The Role of Politics in Judging, Princeton University Press, Princeton, , 2010. the distinctions between formalism and realism are not as stringent as some of the American Legal Realists may have suggested. So already in highly formalist jurisdictions such as Australia we see some blurring of the traditional distinctions between the legislature as responsible for law-making and the judge as responsible for explicating and applying the law.12x See, generally, M. Richardson & A. Kenyon, ‘Fashioning Personality Rights in Australia’, in A. Kenyon, W.L. Ng-Loy & M. Richardson (Eds.), The Law of Reputation and Brands in the Asia Pacific, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2012, p. 86 (arguing that the common law has been developed quite effectively in Australia). And this is certainly the case in jurisdictions such as England (and more generally the UK) as well as New Zealand which, while not abandoning formalism, have in recent decades moved well beyond formalism.

On the other hand, even in the more explicitly realist United States, it is fair to say that much common law development that takes place may be quite subtle and incremental, using what Sunstein refers to as the technique of ‘analogical reasoning’ rather than striking out into the unknown.13x C. Sunstein, ‘On Analogical Reasoning’, 106 Harvard Law Review 1993, p. 741. This is certainly the case for courts below the level of a final court but as Sunstein points out it is also often the case for final courts.14x Ibid., at 742. In short, judges seem often to prefer to rely on the accumulated wisdom of other judges, or at least to use an established precedent as their starting point, albeit in theory they have available the option of coming up with new law to suit their purposes.15x Within the constraints of the constitution and applicable legislation: for even legal realists have not generally gone as far as to argue that judges should have the power to override legislation, although for an interesting attempt see G. Calabresi, A Common Law for the Age of Statutes, Harvard University Press, Boston, 1982. Thus, one essential feature of all common law jurisdictions is that judges feel under constraint when it comes to law reform. They tend to look for subtle ways to press law along to meet the needs of new situations and circumstances. Moreover, if they take upon themselves a more extended law-making function, they feel the need to justify this by reference to exceptional circumstances of the situation. Similarly, while in principle, as Bennett Moses says, “[w]ithin the four corners of the Constitution, Parliament can legislate as it wishes”,16x Bennett Moses, 2003, at 406. I argue below that there is a surprising degree of incrementalism in legislative law reform as well.

This brings me to the object of this article, which is to develop a regulatory theory of law reform that can not only explain when particular techniques of law reform may be selected by legislators or judges in common law jurisdictions such as England (and more generally the UK), Australia and New Zealand, but also say when particular techniques should be preferred.17x The role of administrators in effecting law reform (as opposed to simply recommending and promoting law reform carried out by legislators or judges) is beyond the scope of this article, although it is worthy of separate consideration. For a limited foray see M. Richardson & A. Kenyon, ‘Privacy Online: Reform Beyond Law Reform’, in D. Lindsay et al. (Eds.), Emerging Challenges in Privacy Law: Comparative Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, forthcoming 2013. Since privacy law has become a much discussed topic of possible law reform in recent times, including in these jurisdictions, the article takes privacy law as its case study. Thus the question of whether theorizing about law reform as opposed to theorizing about privacy can lead to improved prospects for effectively reforming the law of privacy for the modern age. -

B. Methodology and Hypotheses

I have posited the need for a regulatory theory of law reform. And a useful starting point here is Ayres and Braithwaite’s influential study of Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate.18x I. Ayres & J. Braithwaite, Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate, Oxford Socio-Legal Studies, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 1992. These authors show how it is possible to find a principled middle ground between extreme positions on the regulation–deregulation divide embodying the more attractive features of both positions while avoiding their pitfalls. Their concern was finding a middle ground between the extremes of strong state regulation of business actors and minimalist regulation that leaves actors free to pursue their own motivations regardless of whether these have to do with the welfare of clients or customers or with private financial gain.19x Ibid., p. 29 (for instance in the case of the management of care homes, research carried out by Braithwaite and his colleagues suggests that the motivations of actors range from ‘exclusively motivated by money’ to ‘exclusively motivated by caring goals’ with a range of more mixed motivations in between those extremes). My concern is with decisions made by legal actors with power to make and remake the law and I am prepared to assume that legal actors will generally have some version of social welfare in mind: the problem is rather whether they can be relied on to achieve good welfare outcome. Specifically, the search is for a middle ground between the extremes of untrammeled powers of law reform, treating decision-makers as having a wide discretion to change the law,20x That is, subject only to the limited constitutional and legislative constraints that apply to courts and the ‘four corners’ of the constitution which constrain even legislators: see generally Calabresi, 1982 and Bennett Moses, 2003, at 406. and very restricted powers of law reform even where reform may be thought desirable. Further, like Ayres and Braithwaite, I accept that the principled middle ground should be based on a real understanding of current structures and practices, should draw on experiences of multiple jurisdictions, and should pay attention to the ‘differing motivations’ of actors.21x Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992, p. 4.

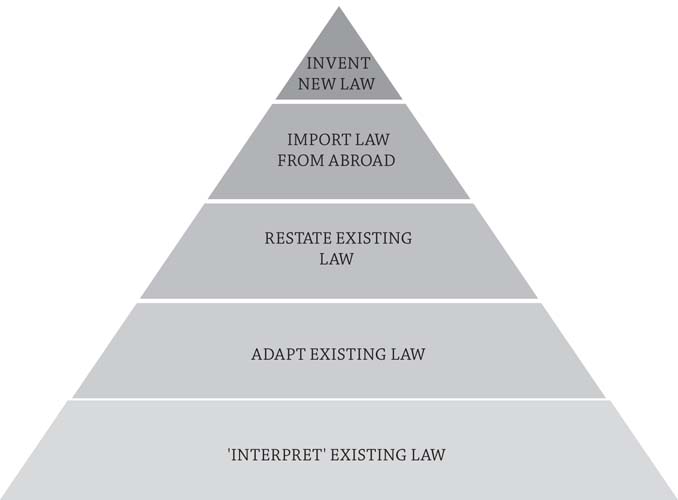

In response to the challenge of locating a principled middle ground between the extremes of strong and minimalist regulation, Ayres and Braithwaite develop a ‘pyramid strategy of responsive regulation’, which represents regulation as a hierarchy of possible regulatory responses ranging from a minimum of, say, self-regulation up to a maximum of, say, command regulation with criminal sanctions.22x Ibid., at p. 39. Another example of the pyramid ranges from persuasion to licence revocation: ibid., at p. 35. On this model, the most minimalist form of regulation comes at the bottom of the pyramid and is given priority on the basis that “where self-regulation works well it is the least burdensome from the point of view of both taxpayers and the regulated industry.”23x Ibid., at p. 38. Moreover, in general, it is argued that a range of possible responses is more likely to elicit cooperative behaviour from actors than a single solution, especially a very stringent solution – the last reserved only for cases where less interventionist techniques do not work. The reasoning can be adapted for the challenge of finding a principled middle ground between extremes of largely unlimited and very limited powers of law reform. So it can be posited that legal decision-makers should have a range of possible techniques at their disposal where the task is adapting law to a changing environment, which can be ordered in a hierarchical fashion as represented by the law reform decision-making pyramid in Figure 1 below – with a general preference for activities at or near the base of the pyramid, moving up the pyramid where more minimalist techniques are insufficient for the task at hand. Figure 1 Example of a Law Reform Decision-Making Pyramid

Figure 1 Example of a Law Reform Decision-Making PyramidShould the range of techniques at the courts’ disposal be restricted compared to those available to legislators? Given their important role in effecting law reform, I would say not, except of course where legislation directly constrains their functions – even though this flies in the face of one of the traditional tenets of legal formalism.24x Cf. G. Hadfield, ‘The Levers of Legal Design: Institutional Determinants of the Quality of Law’, 36 Journal of Comparative Economics 2008, p. 48, arguing that jurisdictions in which courts feel able to adapt their law have more effectively kept law in train with modern conditions. However, the principles of responsive regulation suggest that in both cases the general preference should be for more minimalist techniques of law reform (including some very subtle methods),25x Including, for instance, ‘interpretation’ of existing common law precedent or a statutory provision, which on an extended understanding can be considered ‘reformist’ on the basis that they change the meaning and operation of the precedent or provision: and see Richardson & Kenyon, forthcoming. on the basis that they represent the safest, least burdensome, and least risky form of legal change. The extreme steps of invention of new law – as with other invention – may solve intractable problems, but is a high-cost, risky endeavour. And even importation from abroad may be problematic in requiring the transplantation of legal standards from another jurisdiction into a different social/cultural environment.26x The risks of legal transplants ‘as a tool of law reform’ being a matter on which Kahn-Freund has famously written: ‘On Uses and Misuses of Comparative Law’, 37 Modern Law Review 1974, p. 1. Thus, such techniques should be reserved for cases where more minimalist techniques do not work. So, in general, the argument is for an approach which represents by and large what happens in practice (as discussed in Part A), and which can also be seen to represent a sound approach according to principles of responsive regulation.

We need to be clear that what is being posited is not a coercive regulatory theory of law reform. That is, it is not suggested that legal decision-makers are or should be required to take this approach using a mixture of ‘punish and persuade’ incentives.27x As Ayres and Braithwaite characterize responsive regulation in their discussions: see Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992, Ch. 2. Rather, the argument is simply that this is the approach decision-makers have to quite a large extent selected for themselves – operating on a principle, as Sunstein puts it, that the existing body of legal decisions generally “provides a deep and broad resource for legal thought”.28x Sunstein, 1993, at 789 – with reference especially to common law development, but I am positing that incrementalism is a preferred tool of law reform in the legislative context as well. In general this might be said for decision-making more broadly: e.g., for an argument that administrative decision-makers often prefer incremental over more ambitious top-down decision-making (even when this option is available to them), see C. Lindblom, ‘The Science of “Muddling Through”’, 19 Public Administration Review 1959, p. 79. In other words, the adoption of a pyramid strategy to determine the technique of law reform that should be adopted for a given situation is a form of self-regulation (transcending the minimally restrictive actual regulation imposed by a constitution or, in the case of courts, any relevant legislation in the given jurisdiction). Even so, it is rather an unusual form of self-regulation in regulatory theory terms. In particular, it is not self-regulation that operates in lieu of more coercive regulation from outside – tolerated or condoned by a regulator on the basis that it functions effectively and “is the least burdensome from the point of view of both taxpayers and the regulated industry”.29x See Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992, at 38. Rather, what we see with the adoption by courts and legislatures of this strategy is a pragmatic application to themselves of the same approach that they would generally expect to apply to others whose actions are regulated by their determinations.

In sum, the hypothesis of this article is that law reform will generally follow a minimalist path with more radical steps reserved for exceptional cases where more minimalist approaches have proved unsuccessful. Moreover, it is hypothesized that this approach should work quite effectively in keeping with well-accepted principles of responsive regulation. In the following section of this article the above theory is developed further and applied to the particular context of privacy law reform in Australia, New Zealand and the UK, being an area of potential law reform, which has been the subject of much discussion recently in these jurisdictions. -

C. A Case Study in Privacy Law Reform

The processes of privacy law reform in the three jurisdictions surveyed display the characteristics of law reform noted above: viz of a general preference for more minimalist techniques over more radical ones and of more radical ones being only used where more minimalist ones are felt to be inadequate. Indeed, despite all the rhetoric of radical law reform, privacy law in these jurisdictions has developed in a largely incremental fashion in the post-War era. This is notwithstanding some broader social and cultural transformations including a quite broadly accepted idea of privacy as a human right (albeit the content and scope of the right might be debated),30x See, for instance, (UK) Commission on a Bill of Rights, A UK Bill of Rights? The Choice Before Us, December 2012, available at <www.justice.gov.uk/about/cbr>, Vol. 1, at p. 158 (“The line at which individual privacy should give way to freedom of expression has been debated widely, by the media, Parliament and the public as well as the courts”); (Australia) National Human Rights Consultation Committee, National Human Rights Consultation Report, Commonwealth of Australia, September 2009, available at <www.humanrightsconsultation.gov.au/Report/Documents/NHRCReport.pdf>, pp. 368-369 (listing civil and political rights including the right to ‘privacy and reputation’ as among those widely supported in consultation for inclusion in an Australian Human Rights Act, subject to ‘justified limits’). And for a more cautious assessment of available data, see at 118-119 (suggesting there is broad support for a right to privacy but also concluding that there is a need for further empirical research into actual value attributed to privacy in New Zealand, including whether there is a distinct ‘privacy culture’ in New Zealand). some international legal instruments which make explicit provision for the right,31x Most notably the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, UN General Assembly, Paris, 1948, Art. 12; the European Convention on Human Rights, Rome, 1950, Art. 8; and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, UN General Assembly, New York, 1966, Art. 17. and in the case of the UK domestic legislation in the form of the Human Rights Act 1998 stating that the right to ‘private life’ in Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights is part of UK law,32x Specifically, the Human Rights Act 1998 (UK). as well as various recommendations including from some (governmental) law reform bodies that the law should be framed to better give effect to the right to privacy.33x Although there has been no consensus on the need for statutory reformulation: and see discussion below at notes 45, 52 and 63 for the various recommendations.

The advent of the Human Rights Act may be seen as a radical step in law reform in the UK, reflecting the view at the time that this would be the best way to give effect to the UK’s commitment to the European Convention on Human Rights – although it is worth noting that it did not amount to new law as such, being rather a direct importation of European standards.34x For a more recent recommendation that the UK should develop its own bill of rights, see A UK Bill of Rights?, 2012. (Although interestingly even then it is argued that a UK Bill of Rights would be consistent with a longer tradition of human rights in the UK, long predating the European Convention on Human Rights). Since then courts have generally proceeded by baby steps in refashioning the common law to accommodate its prescriptions. So in the leading House of Lords decision of Campbell v. MGN Ltd.,35x Campbell v. MGN Ltd., [2004] 2 AC 457. the traditional doctrine of breach of confidence was refashioned as a doctrine that protects against unauthorized publicity given to private information in keeping with the Convention’s right to private life with a similarly refashioned public interest defence to accommodate the Convention’s equal right to freedom of expression.36x As provided for expressly in the European Convention on Human Rights, Arts. 8 (2) and 10. And see, generally, G. Phillipson, ‘Privacy in England and Strasbourg Compared’, in A. Kenyon & M. Richardson (Eds.), New Dimensions in Privacy Law: International and Comparative Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2006, p. 184, at pp. 190-191 (noting that Campbell went further than simply confirming that breach of confidence need not be premised on a relationship of confidence, making clear that the doctrine’s operation was premised on the plaintiff’s reasonable expectation of privacy and referring directly to Art. 8 of the Convention). Nor was this treated as an entirely new development. Rather, Lord Goff’s broad statement of breach of confidence as a doctrine about misuse of confidential information subject to a public interest defence in the (pre-Human Rights Act) Spycatcher case37x Attorney-General v. Guardian Newspapers Ltd. (No. 2), [1990] 1 AC 109, Lord Goff at 281-282, giving examples of a private diary or letter which is lost and comes into the hands of another party. And see Hellewell v. Chief Constable of Derbyshire, [1995] 1 WLR 404, at 807, elaborating the reasoning to mean that “[i]f someone with a telephoto lens were to take from a distance and with no authority a picture of another engaged in some private act, his subsequent disclosure of the photograph would, in my judgment, as surely amount to a breach of confidence as if he had found or stolen a letter or diary in which the act was recounted and proceeded to publish it. In such a case, the law would protect what might reasonably be called a right of privacy, although the name accorded to the cause of action would be breach of confidence”. was treated as a starting point for Campbell’s refashioning to further accommodate the relevant rights in the Human Rights Convention. In other words, the Campbell case involved interpretation and adaptation of existing law, namely breach of confidence, to deal with new situations and circumstances of a legally mandated right to privacy – not anything more radical by way of invention (or importation) of new law.38x And see M. Richardson, ‘Towards Legal Pragmatism: Breach of Confidence and the Right to Privacy’, in E. Bant & M. Harding (Eds.), Exploring Private Law, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010, p. 109.

Similarly, when in more recent cases such as McKennitt v. Ash39x McKennitt v. Ash, [2008] QB 73. and Murray v. Express Newspapers Ltd.,40x Murray v. Express Newspapers Plc, [2009] Ch. 481. the Court of Appeal went further to refashion the law derived from Campbell as a tort of misuse of private information framed in terms of a reasonable expectation of privacy to be balanced against freedom of expression, it continued to treat this action as little more than a restatement of existing law (with an element of further adaptation), entailing nothing radical by way of invention of new law.41x And see, generally, T. Aplin et al., Gurry on Breach of Confidence: The Protection of Confidential Information, 2nd edn., Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012, Ch. 2. At the same time, in some of these cases, breach of confidence began to be read as a narrow relational doctrine which operated in tandem with the misuse of privacy tort, a reading which appears to go against the broad reading of breach of confidence in Spycatcher and Campbell. However, the conflict was not expressed and some authority for the narrow reading could be found in earlier cases such as Coco v. A.N. Clark (Engineers) Ltd.,42x Coco v. A.N. Clark (Engineers) Ltd., [1969] RPC 41. where the ‘normal’ elements of breach of confidence were identified as confidential information imparted in a relationship of confidence and then misused, albeit Megarry J did not frame these as immutable boundaries.43x And see Richardson, 2010, noting that this left the way open for the later more expansive development. And there are indications in the most recent jurisprudence that a more refined account may still be given of the relationship between the misuse of privacy tort and the breach of confidence doctrine.44x See, especially, for an effort in this direction, Tchenguiz & Ors v. Imerman, [2011] Fam 116.

Thus courts in England found no need to break clear of established authority in propounding their tort of misuse of private information and distinguishing it from breach of confidence. Rather their ‘new methodology’ has been developing incrementally and quite effectively in stages – a development that is on-going. Moreover, it is an approach that appears to have met with broader approval. So when the opportunity arose in early 2012 to make recommendations for new privacy legislation, a Joint Committee on Privacy and Injunctions determined rather that the refashioning of privacy law in the form of a tort of misuse of private information should be allowed to continue along the current path and that the balance between privacy and free speech could be left to the courts to continue to work out in future cases.45x Joint Committee on Privacy and Injunctions, Privacy and Injunctions, Report, 12 March 2012, available at <www.parliament.uk/jcpi>, pp. 14-19.

In Australia, the courts have been even more explicit that their preferred method is to adapt the existing common law (including equity) to meet the needs of new situations and circumstances, including traditional doctrines such as breach of confidence which for the time being are considered generally sufficient to deal with situations and circumstances regarding the misuse of private information. As Gummow and Hayne JJ said in the leading case of Australian Broadcasting Corporation v. Lenah Game Meats Pty Ltd.,46x Australian Broadcasting Corporation v. Lenah Game Meats Pty Ltd., 208 CLR 199 (2001). “[r]ather than a search to identify the ingredients of a generally expressed wrong, the better course … is to look to the development and adaptation of recognized forms of action to meet new situations and circumstances”.47x 208 CLR 199, at 250. Moreover, added Gleeson CJ, “the law of breach of confidence is [already] adequate to cover the case” where activities filmed are private,48x 208 CLR 199, at 225, citing inter alia Lord Goff in the Spycatcher case and Laws J in Hellewell v. Chief Constable, as quoted at above note 37, as authority for a broad reading of the breach of confidence doctrine as extending to cases including surreptitious or improper obtaining and then misuse of confidential information (i.e., not merely concerned with cases of information imparted in confidence and then misused). pointing to Lord Goff in Spycatcher, although adding that “[t]he law should be more astute than in the past to identify and protect interests of a kind which fall within the concept of privacy”.49x 208 CLR 199, at 225. Thus the process of a mix of a creative ‘interpretation’ and outright adaptation of existing authorities was continued in the case of Australian Broadcasting Corporation v. Lenah Game Meats (and subsequent courts in Australia have largely followed the direction indicated by the High Court).50x See, especially, Giller v. Procopets, 24 VLR 1 (2008). (Special leave to appeal to the High Court was later denied.)

So, for now, the Australian highest court has eschewed any suggestion that a more radical step is needed to protect privacy – at this stage at least (although a privacy cause of action was not ruled out for a suitable case). The fact that in two jurisdictions in Australia, namely the Australian Capital Territory and Victoria, there are now charters of rights which make explicit reference to the right to privacy and reputation51x Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT); Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic). has also not been seen as prompting a new direction in the legal protection of privacy in actual cases – partly because those charters appear to be directed at constraining administrative and legislative activity and partly because the High Court has taken the view that the common law in Australia is a uniform common law rather than a law which may vary across states and territories, making it difficult to imagine it as being subject to the influence of human rights instruments within particular states or territories. Further, attempts by federal and state law reform agencies to see a statutory cause or causes of action for invasion of privacy introduced,52x Australian Law Reform Commission, For Your Information: Australian Privacy Law and Practice, ALRC Report 108, 2008, available at <www.alrc.gov.au/publications/report-108>, Part K (Protection of a Right of Personal Privacy); New South Wales Law Reform Commission, Invasion of Privacy, NSWLRC Report 120, 2009, available at <www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/lawlink/lrc/ll_lrc.nsf/pages/LRC_r120toc>; Victorian Law Reform Commission, Surveillance in Public Places, VLRC Report 18, 2010, available at <www.lawreform.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/Surveillance_final_report.pdf>, Ch. 7 (Statutory Causes of Action). In September 2011 also the Australian Government released an Issues Paper where it invited public response on the question of a statutory cause of action as recommended in the ALRC’s 2008 Report: see Australian Government Issues Paper on a Commonwealth Statutory Cause of Action for Serious Invasion of Privacy, available at <www.dpmc.gov.au/privacy/causeofaction/>. over objection of parts of the media, have so far not resulted in steps being taken by government to implement the recommendations.53x And see D. Rolph, ‘Towards an Australian Law of Privacy: The Arguments For and Against’, 31 Communications Law Bulletin 2012, p. 9, for analysis of the proposals and submissions to the Australian Government Issues Paper, above note 52, concluding that “[t]he treatments of privacy before the courts and the legislature in Australia has reached the position where there is a lot of interest but seemingly little action”: ibid., at 14. And the agencies themselves could not agree as to the terms of any statutory cause (or causes) of action, coming up with several different proposals.54x The proposals differ especially on (1) whether there should be a thresholds of (a) a reasonable expectation of privacy and (b) conduct highly offensive to a reasonable person; (2) whether free speech should be treated as a factor in assessing whether privacy has been invaded rather than a separate defence; and (3) whether there should be a single generally framed privacy cause of action as opposed to specific causes of actions to do with misuse of private information and intrusion. On these issues, the ALRC answered (1) yes, (2) yes, (3) yes; the NSWLRC answered (1) no [just (a)], (2) yes, (3) yes; and the VLRC answered (1) yes, (2) no, (3) no. Thus, the NSWLRC proposals in respect of (1) [but not (2) and (3)] follow the common law development in the English courts after the Human Rights Act; the VLRC proposals come closer to the position as developed by the New Zealand courts (which is to an extent modelled in turn on earlier developments in the US: see below notes 59 and 60) but is also rather English in its language of misuse of private information; and the ALRC sits in between these positions but in respect of (1) follows more the New Zealand line.

Even in New Zealand, where the Court of Appeal embraced a tort of publication of private facts in the case of Hosking v. Runting,55x Hosking v. Runting, [2005] 1 NZLR 1. this was treated as simply continuing a line of authority begun in the lower courts over a period of years. Moreover, it was seen as consistent in substance with what had occurred in the UK in cases to date following the Human Rights Act.56x See, especially, [2005] 1 NZLR, Gault P and Blanchard J, at [90] (“the developments in the United Kingdom, although by a different route, have arrived at a position not substantially different from the recognition of legal protection from publicity of private information. The New Zealand cases have not really gone beyond that.”). In Hosking, the change was made without the special impetus of a human rights charter, for the Bill of Rights Act 1990 (NZ) makes no explicit reference to the right to privacy. However, the courts’ framing of a privacy tort seemed a neat solution to the problem that in New Zealand, unlike the UK and Australia, breach of confidence had been construed as a doctrine limited to relationships of confidence that could not accommodate a broad range of cases of parties obtaining information with knowledge or notice of confidence, as talked about in Spycatcher. Thus it could be argued that a sui generis privacy doctrine was necessary to get around the limitations of breach of confidence.57x As noted in M. Richardson, ‘Privacy and Precedent: The Court of Appeals Decision in Hosking v Runting’, 2005 New Zealand Business Law Quarterly, p. 82. Also worth noting is that the privacy tort embraced in Hosking was not seen as invented law but rather as broadly consistent with the law as developed in the UK to date and as drawing also on the US-style tort of publication of private facts, as set out in the US Restatement on Torts.58x Restatement of the Law, Second, Torts 2d (1977), §652D (Publicity Given to Private Life). Indeed, the latter was explicitly the starting point for the New Zealand tort framed in terms of a reasonable expectation of privacy and conduct highly offensive to a reasonable person, and subject to a public interest defence to accommodate freedom of expression (as required by the Bill of Rights Act).59x [2005] 1 NZLR 1, Gault P and Blanchard J, at [117] (“The elements of the tort as it relates to publicising private information … are a logical development of the attributes identified in the United States jurisprudence”).

In short, when the opportunity was presented to invent new law, the New Zealand Court of Appeal took the relatively cautious line of adapting an existing precedent from another jurisdiction following the line of lower courts,60x And for a similar process of development beginning with respect to intrusion, see C v. Holland, [2012] NZHC 2155, using the intrusion on seclusion tort specified in the US Restatement, above note 58, §652B as a model. and also pointed to parallels that (it was thought) could be found with the UK. Nor was this fashioning of the New Zealand public disclosure tort seen as the end of the incremental process. Rather, Gault P and Blanchard J noted that “[t]he scope of a cause, or causes, of action protecting privacy should be left to incremental development by future Courts”.61x [2005] 1 NZLR 1, Gault P and Blanchard J, at [117]. Subsequently, Elias CJ in Television New Zealand v. Rogers has flagged that certain aspects of the tort might be revisited (namely the stringent threshold of high offensiveness to the reasonable person which the House of Lords in the Campbell case, after Hosking, rejected as an inadequate protection of the right to private life in the European Convention).62x Television New Zealand Ltd. v. Rogers, [2008] 2 NZLR 277, Elias CJ at [25]. But even here, there was no suggestion of radical re-invention, Elias CJ rather stressing that such refashioning could be seen as an incremental process. So there was enough activity at the judicial level – being also activity of an acceptable kind – for the Law Commission, tasked with reviewing New Zealand’s privacy law, to determine that further development of the Hosking v. Runting tort could safely be left to the courts.63x Law Commission, Invasion of Privacy: Penalties and Remedies: Review of the Law of Privacy, Stage 3, NZLC R113, 2010, available at <www.lawcom.govt.nz/project/review-privacy/publication/report/2010/invasion-privacy-penalties-and-remedies-review-law-pr>, R28, at p. 91.

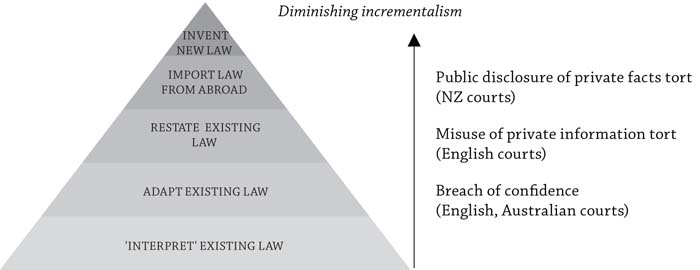

Such ways of reasoning serve to confirm the proposition made earlier (in Part B) that inventing new law to deal with new situations and circumstances is generally seen as the last alternative for law reform in common law jurisdictions such as New Zealand, Australia and the UK, only employed where more incrementalist methods are insufficient. More particularly, in respect of privacy law reform in the jurisdictions surveyed, the idea of developing entirely new law to deal with privacy has been avoided notwithstanding some significant social-cultural developments in favour of privacy, some significant statements in international human rights instruments that privacy is a human right, and in the UK the Human Rights Act giving effect to the right to ‘private life’ in the European Convention. In other words, notwithstanding some quite significant changes in the broader social and legal landscape, relatively low-level techniques of privacy law reform have generally been seen as the best way to modernize – as shown in the law reform pyramid in Figure 2 below. This has certainly been the case for law reform engaged in by the courts, even if some courts have been more reformist than others in adapting their common law. Moreover, a similar pattern can be observed on the legislative side. So law reform bodies tasked with making recommendations for legislative law reform have generally been happy to see the current practices of incremental development continue and in the few instances where more far-reaching reform has been advocated these have so far provoked no action. Figure 2 Example of a Law Reform Decision-Making Pyramid Applied to Privacy Law Reform

Figure 2 Example of a Law Reform Decision-Making Pyramid Applied to Privacy Law Reform -

D. Is More Radical Reform Needed?

The question, then, is at what stage it might become desirable to take a more drastic step. The 2011 phone-hacking scandal in the UK, centered on the Murdoch-owned News of the World tabloid newspaper, led to some public angst about the effectiveness of the current system of press regulation,64x See, generally, R. Keeble & J. Mair (Eds.), The Phone Hacking Scandal: Journalism on Trial, Abramis Academic Publishing, Suffolk, UK, 2012 (although pointing out that the problems go much further to include, as Keeble puts it, “corruption, illegality and distorted news values at the heart of British mainstream journalism”). with the Leveson inquiry established to investigate the question of whether changes would be desirable.65x For the inquiry’s terms of reference, see <www.levesoninquiry.org.uk/about/terms-of-reference/> (although it may be noted that respect for the right to privacy is not specifically mentioned as one of the goals). But in Australia, in the wake of the phone-hacking scandal, the Government released an Issues Paper on A Commonwealth Statutory Cause of Action for Serious Invasion of Privacy,66x Australian Government Issues Paper on a Commonwealth Statutory Cause of Action for Serious Invasion of Privacy, above note 52. inviting submissions on the question of a statutory privacy cause of action as recommended by the Australian Law Reform Commission. However, even then the public response to the Issues Paper was not strongly in support of a statutory cause of action, and some parts of the media were opposed (including the Murdoch-owned Australian newspaper).67x See Rolph, 2012, for an analysis of key submissions. Indeed, there seems little support for this to happen now in Australia. More recently, the international scandal of two Sydney-based radio journalists making a hoax call to a London hospital and deceiving staff into releasing private information about the pregnant Princess Kate’s health status in late 2012, with one person tragically committing suicide as this became known,68x See ‘2DAY FM in Crisis Over Prank Call “Tragedy”’, ABC News, 10 December 2012, available at <www.abc.net.au/news/2012-12-09/2day-fm-responds-to-growing-royal-hoax-backlash/4417610>. has not led to further serious talk of a statutory privacy cause of action in Australia – notwithstanding that health privacy information is generally seen as among the most sensitive forms of private information, and the conduct of the radio station and its journalists was widely criticized, especially after the nurse’s suicide became known.69x Nor was this a single case of bad behaviour on the part of Station 2DAY FM and its licence-holder Southern Cross Austereo, although it was the one that had the most tragic consequences. As D. Miller of the Centre for Applied Policy and Public Ethics at The University of Melbourne puts it, 2DAY FM and Southern Cross (and their managers and directors) have over a period of years and through a series of incidents collectively “created a culture of reckless indifference to the welfare of others and contempt for norms of decency”: ‘Did 2Day FM Break the Law? And Does it Matter?’, The Conversation, 11 December 2012, available at <http://theconversation.edu.au/did-2day-fm-break-the-law-and-does-it-matter-11250>. Others have suggested that the culture has spread further: for instance, B. McNair (Professor of Journalism at Queensland University of Technology), ‘Leveson Must Lead to Cultural Change for Press and Public’, The Conversation, 14 December 2012, available at <http://theconversation.edu.au/leveson-must-lead-to-cultural-change-for-press-and-public-11303> (referring to “a moral deficit at the core of much media practice in this country”).

Here it may be useful to compare an earlier period of scandalous press activity when radical privacy law reform was advocated as an exceptional response to an exceptional situation. That is the period when Warren and Brandeis of Boston wrote their famous article on ‘The Right to Privacy’ published in the 1890 Harvard Law Review,70x S. Warren & L. Brandeis, ‘The Right to Privacy’, 4 Harvard Law Review 1890, p. 193. an article that was to have a profound influence on the development of privacy law in the United States throughout the course of the 20th century, including the introduction of a range of new privacy torts (including of public disclosure of private facts and intrusion on seclusion). Specifically, the authors argued that:71x Ibid., at 195.Recent inventions and business methods call attention to the next step which must be taken for the protection of the person, and for securing to the individual … the right “to be let alone”. Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life; and numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that “what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops”.

Moreover, Warren and Brandeis added, the crisis was not just a matter of the notorious American ‘yellow press’,72x And see E. Godkin, ‘The Rights of the Citizen. IV To His Own Reputation’, 8 Scribner’s Magazine 1890, p. 65, at 66 (the newspaper press has converted what was previously merely curiosity and gossip into ‘effectual demand’ and a ‘marketable commodity’). The article is cited by Warren & Brandeis, 1890, at 195 as “an example of the evil of the invasion of privacy by newspapers … recently discussed by an able writer”. and the wide-spread use of popular camera technologies (especially after Eastman’s invention of the easy-to-use portable camera, priced and marketed to satisfy popular demand),73x See R. Mensel, ‘“Kodakers Lying in Wait”: Amateur Photography and the Right of Privacy in New York, 1885-1915’, 43 American Quarterly 1991, p. 24, at 27-32 especially (noting that “[c]learly technological innovation and market expansion in the … photography industries provided some of the conditions for the development of the right to privacy”, including in particular Eastman’s deliberate efforts to create massive consumer demand for his new product coupled the “enormous … market in photographs”, helping to create a class of “Kodak fiends”). but also developing social attitudes to privacy – for “each crop of unseemly gossip … [once harvested] becomes the seed of more, and in direct proportion to its circulation, results in a lowering of social standards and of morality”.74x Warren & Brandeis, 1890, at 196. In the face of these transformations, they insisted that current laws were inadequate to deal with privacy.75x Note that this is premised on a narrow interpretation of existing authorities: and see ibid., at 210-212. But then these authorities were rather narrowly confined in the late 19th century: e.g., the trend in breach of confidence’s development away from a broader mid-century doctrine based around flexible ideas of trust and confidence to a narrower relational doctrine except where a specific ‘property right’ could be identified, are discussed in M. Richardson et al., Breach of Confidence: Social Origins and Modern Developments, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, 2012, Ch. 4 (Secrecy and Late Victorian markets for information). Instead, new law was needed that recognized explicitly the right to privacy as a right to be ‘let alone’, reflecting a principle of ‘inviolate personality’.76x Warren & Brandeis, 1890, at 205. So, it was argued, the combination of practices, social norms and doctrinal inadequacy combined to create a persuasive case for new law that would explicitly recognize and give effect to ‘the right to privacy’ as its modern approach77x Although interestingly even Warren & Brandeis did not advocate a complete break with existing law, arguing rather that a privacy tort was the logical next step in refashioning doctrines such as breach of confidence and property right in unpublished works: see Warren & Brandeis, 1890, at 206 (“the existing law affords a principle which may be invoked to protect the privacy of the individual from invasion either by the too enterprising press, the photographer, or the possessor of any other modern device for recording or reproducing scenes or sounds”). – an argument that could appeal to scholars and judges beginning to explore ideas of Legal Realism.

On the other hand, the American privacy torts exhibited the problems of inventing new law. The framing of ‘privacy’ in the US Restatement as “the interest of the individual in leading, to some reasonable extent, a secluded and private life, free from the prying eyes, ears and publications of others”78x Restatement of Torts, above note 58, at p. 377. has been criticized as insufficiently determinate to guarantee any level of privacy protection; and some have questioned whether the torts of intrusion on seclusion and publication of private facts (the main privacy torts) have actually provided much by way of protection of privacy, given all the thresholds and limitations designed to ensure that freedom of speech and the media is given significant weight as constitutionally mandated by the First Amendment.79x See, for an excellent summary and elaboration of the arguments, J. Mills, Privacy: The Lost Right, Oxford University Press, New York, 2008 – pointing, for instance, to the threshold requirement of high offensiveness to the reasonable person, and also the very broadly construed newsworthiness/public figure defence to the latter tort (combined also with a very broad reading of the First Amendment’s right to free speech and media). Certainly the torts appear to offer less by way of privacy protection than what Warren and Brandies had in mind.80x Especially with respect to the tort of public disclosure of private facts, the focus of their article as pointed out by W. Prosser, ‘Privacy’, 48 California Law Review 1960, p. 383. Prosser as author of the latter article and chief reporter of the Restatement of Torts had his own influence on the law: and see N. Richards & D. Solove, ‘Prosser’s Privacy Law: A Mixed Legacy’, 98 California Law Review 2010, p. 1887, at 1887 (“Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis may have popularized privacy in American law … but Prosser was the law’s chief architect”). Arguably, this shows how a community’s values may influence the development of law over time. As Anderson says, Americans may value privacy, but they value freedom of speech and the media more.81x D. Anderson, ‘The Failure of American Privacy Law’, in B. Markesinis (Ed.), Protecting Privacy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999, p. 139, at 143 (“some invasions of privacy result from excessive media zeal, but most result from our own zeal – our collective appetite for information and our civic commitment to free speech”). And Whitman has gone further to posit that US law’s limited protection of privacy (mostly focused on the home and against the state) reflects a peculiarly American libertarian culture of privacy, being a culture that is quite different from the more dignitarian European culture of privacy notwithstanding Warren and Brandeis’ (dignitarian) language of privacy as a matter of ‘inviolate personality’.82x J. Whitman, ‘The Two Western Cultures of Privacy: Dignity Versus Liberty’, 113 Yale Law Journal 2004, p. 1151. But the experience of US privacy law also shows that even a dedicated privacy cause of action may not do a great deal in practice to regulate certain activities of the media vis-à-vis privacy. Indeed the same can be said of the more incrementally developed New Zealand public facts tort, and for that matter the English tort of misuse of private information and Australian breach of confidence doctrine – neither of which managed to avert the recent media scandals.

This brings us to a more general question of the effectiveness of a privacy cause of action in the modern age. Certainly, we might hope that if a privacy protection is to continue to move in this direction in jurisdictions such as New Zealand and England (and generally the UK) and ultimately perhaps Australia, there would be some searching analysis of social attitudes to ‘privacy’ and ‘free expression’ given that the US experience shows how these may crucially influence the law’s scope and application.83x See the New Zealand Law Commission in its study paper, Privacy: Concepts and Issues: Review of the Law of Privacy, Stage 1, 2008, available at <www.lawcom.govt.nz/project/review-privacy/publication/study-paper/2008/privacy-concepts-and-issues>, p. 120 (“more research is needed into attitudes to privacy in New Zealand, including the history of privacy in this country, the influence of culture on attitudes, the views of New Zealand young people and the impact of new technologies on those views … [and] whether there is a distinct ‘privacy culture’ in New Zealand, shaped by our history, cultural makeup and small population size”). That is not to say that there may not be reasons going beyond social values that could justify a privacy cause of action, especially one that is well framed and backed up with good institutional support. But it may be that other reforms of law will be more effective when it comes to certain kinds of conduct that currently appear to be highly resistant to current legal controls. Data protection law is an example. Elsewhere I have argued that expanded legal data protection can provide a logical way to address problematic business dealings with personal information on the internet, as seems to be happening in Europe.84x Richardson & Kenyon, forthcoming. Similarly, it may be argued that more expansive media regulation may be more effective than a simple privacy cause of action to offset the systemic problems that became apparent with the UK’s phone-hacking scandal and the Sydney radio-hoax scandal – in other words, that principles of responsive regulation should be applied to the media, although light-handed regulation may do the job well enough in the general run of things.

A new system of responsive regulation of the press in the UK is what the Leveson Committee has recommended in its report following the phone-hacking scandal.85x The Right Honourable Lord Justice Leveson, An Inquiry into the Culture, Practices and Ethics of the Press, Report, November 2012, available at <www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/hc1213/hc07/0780/0780.asp>, especially Vol. 4, Part K, Ch. 7 (Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Regulation), recommending a system of voluntary, independent self-regulation backed by statute and with regulatory oversight, which applies standards publicly set out in a standards code. In Australia as well there have been recommendations for more expansive regulatory controls over the media, with explicit reference made to Ayres and Braithwaite’s principles of responsive regulation.86x See The Hon R. Finkelstein QC assisted by M. Ricketson, Report of the Independent Inquiry into the Media and Media Regulation, Report to the Minister for Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy, 28 February 2012, available at <www.dbcde.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/146994/Report-of-the-Independent-Inquiry-into-the-Media-and-Media-Regulation-web.pdf>, Ch. 11 (Reform), recommending a system of ‘enforced self-regulation’ for the Australian media backed by statute and with regulatory oversight. It is not my purpose in this article to evaluate and compare this system with that proposed by Lord Leveson. And, although it may be debated whether the recommendations will lead to a new system any time soon,87x Or indeed whether that is desirable – or whether an improved system could be devised. if the result is that the threat of this will lead to more rigorous application and further development of the current system, that in itself may be viewed as an improvement. -

E. Concluding Comments

Ayres and Braithwaite observe in Responsive Regulation that regulation should be responsive to industry structures and practices as well as the differing motivations of regulated actors.88x Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992, p. 4. And in their model of a pyramid strategy of responsive regulation they propound an idea of minimalist regulation escalating up to a final solution only where more minimalist options do not work. In this article, I put forward a theory of responsive law reform for common law jurisdictions, which suggests that, as a matter of self-regulation, courts and legislators tend to prefer minimalist forms of law reform and only move to more radical measures if more modest solutions are found ineffective. The model appears to have a useful explanatory power when it comes to a case study of law reform in respect of privacy and the media with particular reference to law reform in Australia, New Zealand and England (and generally the UK).

Of course, privacy law reform cannot be a panacea for all the regulatory challenges involving the media. With the phone-hacking scandal in the UK and the radio-hoax scandal in Australia, we may have reached a point where current regulatory mechanisms are inadequate to control certain practices of the media, including some that may impact on privacy – but further reform of privacy law seems to offer little prospect of improvement. Will the result be a new system of media regulation? At very least we may see some adjustment of the current system, while not surrendering the benefits of minimalist regulation in the general run of things. -

1 See, for a summary, B. Markesinis, Comparative Law in the Courtroom and the Classroom: The Story of the Last Thirty-Five Years, Hart Publishing, Oxford, 2003.

-

2 And see R. Michaels, ‘The Second Wave of Comparative Law and Economics?’, 59 University of Toronto Law Journal 2009, p. 197, at pp. 200-201 especially.

-

3 See, for instance, as to New Zealand and Australia, A. Grimes, L. Wevers & G. Sillivan (Eds.), States of Mind: Australia and New Zealand 1901-2001, Institute of Policy Studies, Wellington, 2002.

-

4 O. Kahn-Freund, Comparative Law as an Academic Subject, Inaugural Lecture delivered at the University of Oxford, 12 May 1965, Clarendon Press, Oxford, p. 8.

-

5 L. Bennett Moses, ‘Agents of Change: How the Law “Copes” With Technological Change’, 20 Griffith Law Review 2011, p. 763; S. Ricketson, ‘The Future of Australian Intellectual Property Law Reform and Administration’, 3 Australian Intellectual Property Journal 1992, p. 1.

-

6 L. Bennett Moses, ‘Adapting the Law to Technological Change: A Comparison of Common Law and Legislation’, 2003 University of New South Wales Law Journal, p. 394.

-

7 O. Kahn-Freund, ‘Legislation Through Adjudication: The Legal Aspects of Fair Wages Clauses and Recognised Conditions’, 11 Modern Law Review 1948, p. 269, at p. 270.

-

8 Ricketson, 1992, noting especially that New Zealand’s historical record on intellectual property law reform has often historically been more nimble and experimental than that of Australia. And see also, S. Frankel & M. Richardson, ‘Limits of Free Trade Agreements: The New Zealand/Australia Experience’, in C. Antons & R. Hilty (Eds.), Intellectual Property Aspects of Free Trade Agreements in the Asia-Pacific Region, Kluwer Law International, Alphen aan den Rijn, forthcoming 2013 (New Zealand more intent on determining the ‘best model’).

-

9 W. Fisher, M. Horwitz & T. Reed (Eds.), American Legal Realism, Oxford University Press, New York, p. xv.

-

10 Of course in traditional formalist terms judges do not function as legislators – and see Bennett Moses, 2003, at 406, citing Gaudron and McHugh JJ in Breen v. Williams, 186 CLR 71, 115 (1996). But even the High Court has hinted at its ability to create new law in exceptional circumstances (while continuing to express a preference for incrementalism); see, e.g., Australian Broadcasting Corporation v. Lenah Game Meats Pty Ltd., 208 CLR 199 (2001), Gummow and Hayne JJ at [132].

-

11 B. Tamanaha, Beyond the Formalist-Realist Divide: The Role of Politics in Judging, Princeton University Press, Princeton, , 2010.

-

12 See, generally, M. Richardson & A. Kenyon, ‘Fashioning Personality Rights in Australia’, in A. Kenyon, W.L. Ng-Loy & M. Richardson (Eds.), The Law of Reputation and Brands in the Asia Pacific, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2012, p. 86 (arguing that the common law has been developed quite effectively in Australia).

-

13 C. Sunstein, ‘On Analogical Reasoning’, 106 Harvard Law Review 1993, p. 741.

-

14 Ibid., at 742.

-

15 Within the constraints of the constitution and applicable legislation: for even legal realists have not generally gone as far as to argue that judges should have the power to override legislation, although for an interesting attempt see G. Calabresi, A Common Law for the Age of Statutes, Harvard University Press, Boston, 1982.

-

16 Bennett Moses, 2003, at 406.

-

17 The role of administrators in effecting law reform (as opposed to simply recommending and promoting law reform carried out by legislators or judges) is beyond the scope of this article, although it is worthy of separate consideration. For a limited foray see M. Richardson & A. Kenyon, ‘Privacy Online: Reform Beyond Law Reform’, in D. Lindsay et al. (Eds.), Emerging Challenges in Privacy Law: Comparative Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, forthcoming 2013.

-

18 I. Ayres & J. Braithwaite, Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate, Oxford Socio-Legal Studies, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 1992.

-

19 Ibid., p. 29 (for instance in the case of the management of care homes, research carried out by Braithwaite and his colleagues suggests that the motivations of actors range from ‘exclusively motivated by money’ to ‘exclusively motivated by caring goals’ with a range of more mixed motivations in between those extremes).

-

20 That is, subject only to the limited constitutional and legislative constraints that apply to courts and the ‘four corners’ of the constitution which constrain even legislators: see generally Calabresi, 1982 and Bennett Moses, 2003, at 406.

-

21 Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992, p. 4.

-

22 Ibid., at p. 39. Another example of the pyramid ranges from persuasion to licence revocation: ibid., at p. 35.

-

23 Ibid., at p. 38.

-

24 Cf. G. Hadfield, ‘The Levers of Legal Design: Institutional Determinants of the Quality of Law’, 36 Journal of Comparative Economics 2008, p. 48, arguing that jurisdictions in which courts feel able to adapt their law have more effectively kept law in train with modern conditions.

-

25 Including, for instance, ‘interpretation’ of existing common law precedent or a statutory provision, which on an extended understanding can be considered ‘reformist’ on the basis that they change the meaning and operation of the precedent or provision: and see Richardson & Kenyon, forthcoming.

-

26 The risks of legal transplants ‘as a tool of law reform’ being a matter on which Kahn-Freund has famously written: ‘On Uses and Misuses of Comparative Law’, 37 Modern Law Review 1974, p. 1.

-

27 As Ayres and Braithwaite characterize responsive regulation in their discussions: see Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992, Ch. 2.

-

28 Sunstein, 1993, at 789 – with reference especially to common law development, but I am positing that incrementalism is a preferred tool of law reform in the legislative context as well. In general this might be said for decision-making more broadly: e.g., for an argument that administrative decision-makers often prefer incremental over more ambitious top-down decision-making (even when this option is available to them), see C. Lindblom, ‘The Science of “Muddling Through”’, 19 Public Administration Review 1959, p. 79.

-

29 See Ayres & Braithwaite, 1992, at 38.

-

30 See, for instance, (UK) Commission on a Bill of Rights, A UK Bill of Rights? The Choice Before Us, December 2012, available at <www.justice.gov.uk/about/cbr>, Vol. 1, at p. 158 (“The line at which individual privacy should give way to freedom of expression has been debated widely, by the media, Parliament and the public as well as the courts”); (Australia) National Human Rights Consultation Committee, National Human Rights Consultation Report, Commonwealth of Australia, September 2009, available at <www.humanrightsconsultation.gov.au/Report/Documents/NHRCReport.pdf>, pp. 368-369 (listing civil and political rights including the right to ‘privacy and reputation’ as among those widely supported in consultation for inclusion in an Australian Human Rights Act, subject to ‘justified limits’). And for a more cautious assessment of available data, see at 118-119 (suggesting there is broad support for a right to privacy but also concluding that there is a need for further empirical research into actual value attributed to privacy in New Zealand, including whether there is a distinct ‘privacy culture’ in New Zealand).

-

31 Most notably the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, UN General Assembly, Paris, 1948, Art. 12; the European Convention on Human Rights, Rome, 1950, Art. 8; and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, UN General Assembly, New York, 1966, Art. 17.

-

32 Specifically, the Human Rights Act 1998 (UK).

-

33 Although there has been no consensus on the need for statutory reformulation: and see discussion below at notes 45, 52 and 63 for the various recommendations.

-

34 For a more recent recommendation that the UK should develop its own bill of rights, see A UK Bill of Rights?, 2012. (Although interestingly even then it is argued that a UK Bill of Rights would be consistent with a longer tradition of human rights in the UK, long predating the European Convention on Human Rights).

-

35 Campbell v. MGN Ltd., [2004] 2 AC 457.

-

36 As provided for expressly in the European Convention on Human Rights, Arts. 8 (2) and 10. And see, generally, G. Phillipson, ‘Privacy in England and Strasbourg Compared’, in A. Kenyon & M. Richardson (Eds.), New Dimensions in Privacy Law: International and Comparative Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2006, p. 184, at pp. 190-191 (noting that Campbell went further than simply confirming that breach of confidence need not be premised on a relationship of confidence, making clear that the doctrine’s operation was premised on the plaintiff’s reasonable expectation of privacy and referring directly to Art. 8 of the Convention).

-

37 Attorney-General v. Guardian Newspapers Ltd. (No. 2), [1990] 1 AC 109, Lord Goff at 281-282, giving examples of a private diary or letter which is lost and comes into the hands of another party. And see Hellewell v. Chief Constable of Derbyshire, [1995] 1 WLR 404, at 807, elaborating the reasoning to mean that “[i]f someone with a telephoto lens were to take from a distance and with no authority a picture of another engaged in some private act, his subsequent disclosure of the photograph would, in my judgment, as surely amount to a breach of confidence as if he had found or stolen a letter or diary in which the act was recounted and proceeded to publish it. In such a case, the law would protect what might reasonably be called a right of privacy, although the name accorded to the cause of action would be breach of confidence”.

-

38 And see M. Richardson, ‘Towards Legal Pragmatism: Breach of Confidence and the Right to Privacy’, in E. Bant & M. Harding (Eds.), Exploring Private Law, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010, p. 109.

-

39 McKennitt v. Ash, [2008] QB 73.

-

40 Murray v. Express Newspapers Plc, [2009] Ch. 481.

-

41 And see, generally, T. Aplin et al., Gurry on Breach of Confidence: The Protection of Confidential Information, 2nd edn., Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012, Ch. 2.

-

42 Coco v. A.N. Clark (Engineers) Ltd., [1969] RPC 41.

-

43 And see Richardson, 2010, noting that this left the way open for the later more expansive development.

-

44 See, especially, for an effort in this direction, Tchenguiz & Ors v. Imerman, [2011] Fam 116.

-

45 Joint Committee on Privacy and Injunctions, Privacy and Injunctions, Report, 12 March 2012, available at <www.parliament.uk/jcpi>, pp. 14-19.

-

46 Australian Broadcasting Corporation v. Lenah Game Meats Pty Ltd., 208 CLR 199 (2001).

-

47 208 CLR 199, at 250.

-

48 208 CLR 199, at 225, citing inter alia Lord Goff in the Spycatcher case and Laws J in Hellewell v. Chief Constable, as quoted at above note 37, as authority for a broad reading of the breach of confidence doctrine as extending to cases including surreptitious or improper obtaining and then misuse of confidential information (i.e., not merely concerned with cases of information imparted in confidence and then misused).

-

49 208 CLR 199, at 225.

-

50 See, especially, Giller v. Procopets, 24 VLR 1 (2008). (Special leave to appeal to the High Court was later denied.)

-

51 Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT); Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic).

-

52 Australian Law Reform Commission, For Your Information: Australian Privacy Law and Practice, ALRC Report 108, 2008, available at <www.alrc.gov.au/publications/report-108>, Part K (Protection of a Right of Personal Privacy); New South Wales Law Reform Commission, Invasion of Privacy, NSWLRC Report 120, 2009, available at <www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/lawlink/lrc/ll_lrc.nsf/pages/LRC_r120toc>; Victorian Law Reform Commission, Surveillance in Public Places, VLRC Report 18, 2010, available at <www.lawreform.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/Surveillance_final_report.pdf>, Ch. 7 (Statutory Causes of Action). In September 2011 also the Australian Government released an Issues Paper where it invited public response on the question of a statutory cause of action as recommended in the ALRC’s 2008 Report: see Australian Government Issues Paper on a Commonwealth Statutory Cause of Action for Serious Invasion of Privacy, available at <www.dpmc.gov.au/privacy/causeofaction/>.

-

53 And see D. Rolph, ‘Towards an Australian Law of Privacy: The Arguments For and Against’, 31 Communications Law Bulletin 2012, p. 9, for analysis of the proposals and submissions to the Australian Government Issues Paper, above note 52, concluding that “[t]he treatments of privacy before the courts and the legislature in Australia has reached the position where there is a lot of interest but seemingly little action”: ibid., at 14.

-

54 The proposals differ especially on (1) whether there should be a thresholds of (a) a reasonable expectation of privacy and (b) conduct highly offensive to a reasonable person; (2) whether free speech should be treated as a factor in assessing whether privacy has been invaded rather than a separate defence; and (3) whether there should be a single generally framed privacy cause of action as opposed to specific causes of actions to do with misuse of private information and intrusion. On these issues, the ALRC answered (1) yes, (2) yes, (3) yes; the NSWLRC answered (1) no [just (a)], (2) yes, (3) yes; and the VLRC answered (1) yes, (2) no, (3) no. Thus, the NSWLRC proposals in respect of (1) [but not (2) and (3)] follow the common law development in the English courts after the Human Rights Act; the VLRC proposals come closer to the position as developed by the New Zealand courts (which is to an extent modelled in turn on earlier developments in the US: see below notes 59 and 60) but is also rather English in its language of misuse of private information; and the ALRC sits in between these positions but in respect of (1) follows more the New Zealand line.

-

55 Hosking v. Runting, [2005] 1 NZLR 1.

-

56 See, especially, [2005] 1 NZLR, Gault P and Blanchard J, at [90] (“the developments in the United Kingdom, although by a different route, have arrived at a position not substantially different from the recognition of legal protection from publicity of private information. The New Zealand cases have not really gone beyond that.”).

-

57 As noted in M. Richardson, ‘Privacy and Precedent: The Court of Appeals Decision in Hosking v Runting’, 2005 New Zealand Business Law Quarterly, p. 82.

-

58 Restatement of the Law, Second, Torts 2d (1977), §652D (Publicity Given to Private Life).

-

59 [2005] 1 NZLR 1, Gault P and Blanchard J, at [117] (“The elements of the tort as it relates to publicising private information … are a logical development of the attributes identified in the United States jurisprudence”).

-

60 And for a similar process of development beginning with respect to intrusion, see C v. Holland, [2012] NZHC 2155, using the intrusion on seclusion tort specified in the US Restatement, above note 58, §652B as a model.

-

61 [2005] 1 NZLR 1, Gault P and Blanchard J, at [117].

-

62 Television New Zealand Ltd. v. Rogers, [2008] 2 NZLR 277, Elias CJ at [25].

-

63 Law Commission, Invasion of Privacy: Penalties and Remedies: Review of the Law of Privacy, Stage 3, NZLC R113, 2010, available at <www.lawcom.govt.nz/project/review-privacy/publication/report/2010/invasion-privacy-penalties-and-remedies-review-law-pr>, R28, at p. 91.

-

64 See, generally, R. Keeble & J. Mair (Eds.), The Phone Hacking Scandal: Journalism on Trial, Abramis Academic Publishing, Suffolk, UK, 2012 (although pointing out that the problems go much further to include, as Keeble puts it, “corruption, illegality and distorted news values at the heart of British mainstream journalism”).

-

65 For the inquiry’s terms of reference, see <www.levesoninquiry.org.uk/about/terms-of-reference/> (although it may be noted that respect for the right to privacy is not specifically mentioned as one of the goals).

-

66 Australian Government Issues Paper on a Commonwealth Statutory Cause of Action for Serious Invasion of Privacy, above note 52.

-

67 See Rolph, 2012, for an analysis of key submissions.

-

68 See ‘2DAY FM in Crisis Over Prank Call “Tragedy”’, ABC News, 10 December 2012, available at <www.abc.net.au/news/2012-12-09/2day-fm-responds-to-growing-royal-hoax-backlash/4417610>.

-

69 Nor was this a single case of bad behaviour on the part of Station 2DAY FM and its licence-holder Southern Cross Austereo, although it was the one that had the most tragic consequences. As D. Miller of the Centre for Applied Policy and Public Ethics at The University of Melbourne puts it, 2DAY FM and Southern Cross (and their managers and directors) have over a period of years and through a series of incidents collectively “created a culture of reckless indifference to the welfare of others and contempt for norms of decency”: ‘Did 2Day FM Break the Law? And Does it Matter?’, The Conversation, 11 December 2012, available at <http://theconversation.edu.au/did-2day-fm-break-the-law-and-does-it-matter-11250>. Others have suggested that the culture has spread further: for instance, B. McNair (Professor of Journalism at Queensland University of Technology), ‘Leveson Must Lead to Cultural Change for Press and Public’, The Conversation, 14 December 2012, available at <http://theconversation.edu.au/leveson-must-lead-to-cultural-change-for-press-and-public-11303> (referring to “a moral deficit at the core of much media practice in this country”).

-

70 S. Warren & L. Brandeis, ‘The Right to Privacy’, 4 Harvard Law Review 1890, p. 193.

-

71 Ibid., at 195.

-

72 And see E. Godkin, ‘The Rights of the Citizen. IV To His Own Reputation’, 8 Scribner’s Magazine 1890, p. 65, at 66 (the newspaper press has converted what was previously merely curiosity and gossip into ‘effectual demand’ and a ‘marketable commodity’). The article is cited by Warren & Brandeis, 1890, at 195 as “an example of the evil of the invasion of privacy by newspapers … recently discussed by an able writer”.

-

73 See R. Mensel, ‘“Kodakers Lying in Wait”: Amateur Photography and the Right of Privacy in New York, 1885-1915’, 43 American Quarterly 1991, p. 24, at 27-32 especially (noting that “[c]learly technological innovation and market expansion in the … photography industries provided some of the conditions for the development of the right to privacy”, including in particular Eastman’s deliberate efforts to create massive consumer demand for his new product coupled the “enormous … market in photographs”, helping to create a class of “Kodak fiends”).

-

74 Warren & Brandeis, 1890, at 196.

-

75 Note that this is premised on a narrow interpretation of existing authorities: and see ibid., at 210-212. But then these authorities were rather narrowly confined in the late 19th century: e.g., the trend in breach of confidence’s development away from a broader mid-century doctrine based around flexible ideas of trust and confidence to a narrower relational doctrine except where a specific ‘property right’ could be identified, are discussed in M. Richardson et al., Breach of Confidence: Social Origins and Modern Developments, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, 2012, Ch. 4 (Secrecy and Late Victorian markets for information).

-

76 Warren & Brandeis, 1890, at 205.

-

77 Although interestingly even Warren & Brandeis did not advocate a complete break with existing law, arguing rather that a privacy tort was the logical next step in refashioning doctrines such as breach of confidence and property right in unpublished works: see Warren & Brandeis, 1890, at 206 (“the existing law affords a principle which may be invoked to protect the privacy of the individual from invasion either by the too enterprising press, the photographer, or the possessor of any other modern device for recording or reproducing scenes or sounds”).

-

78 Restatement of Torts, above note 58, at p. 377.

-

79 See, for an excellent summary and elaboration of the arguments, J. Mills, Privacy: The Lost Right, Oxford University Press, New York, 2008 – pointing, for instance, to the threshold requirement of high offensiveness to the reasonable person, and also the very broadly construed newsworthiness/public figure defence to the latter tort (combined also with a very broad reading of the First Amendment’s right to free speech and media).

-

80 Especially with respect to the tort of public disclosure of private facts, the focus of their article as pointed out by W. Prosser, ‘Privacy’, 48 California Law Review 1960, p. 383. Prosser as author of the latter article and chief reporter of the Restatement of Torts had his own influence on the law: and see N. Richards & D. Solove, ‘Prosser’s Privacy Law: A Mixed Legacy’, 98 California Law Review 2010, p. 1887, at 1887 (“Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis may have popularized privacy in American law … but Prosser was the law’s chief architect”).

-

81 D. Anderson, ‘The Failure of American Privacy Law’, in B. Markesinis (Ed.), Protecting Privacy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999, p. 139, at 143 (“some invasions of privacy result from excessive media zeal, but most result from our own zeal – our collective appetite for information and our civic commitment to free speech”).

-

82 J. Whitman, ‘The Two Western Cultures of Privacy: Dignity Versus Liberty’, 113 Yale Law Journal 2004, p. 1151.

-