-

A. Introduction

Laws are the essential threads that bind together our society. They provide the framework of democratically inspired and enforced rules that define us as a nation and mediate relations between each of us as citizen. Though we may not be readily conscious of it, a wide variety of laws impinge on our public and private lives each and every day. … And yet, despite their fundamental importance to us all, the process by which we make laws in this country is deeply flawed.1x See R. Fox & M. Korris, Making Better Law: Reform of the Legislative Process from Policy to Act, Hansard Society, London, 2010, p. 13.

In a country, where there are people with different ideologies, interests, concerns and faiths living together, a set of rules that regulates, guides and controls their conduct is crucial and significant. Without such a rule, the people with conflicting interests and faiths would be free to make their decisions on the basis of their principles and act as they wish. The consequence of this is that it might cause chaos and disorder in society, which in the end could result in the collapse of society.

There is no doubt that governments with their powers and capacities may issue directions, orders and guidelines regarding their policies over any matter. But without such a force of law, the directions, orders and guidelines issued may be in vain. Therefore, governments need legislation to give effect to their decided policies.2x Miers & Page argue that the government “needs legislation to give legal effect to its policies, to clothe them with the force of law”. See D.R. Miers & A.C. Page, Legislation (2nd edn), Sweet & Maxwell, London, 1990, p. 11. In other words, governments have to translate their policies into legislation because of the demands of legitimacy, and also because governments cannot govern without laws.3x See A. Seidman, R.B. Seidman & N. Abeyesekere, Legislative Drafting for Democratic Social Change: A Manual for Drafters, Kluwer Law International, London, 2001, pp. 13-14. See also Crabbe where he states that “Generally speaking, legislation is the normal means by which the government is able to govern … no government could last long without the power to make laws for the good order and governance of a particular jurisdiction in accordance with political exigencies. It may indeed be said that legislation and government are complementary aspect of the same social process. However little a part it plays, legislation is still an important, if not a critical, aspect of process of modern government.” V.C.R.A.C. Crabbe, Legislative Drafting, Cavendish Publishing Ltd., London, 1993, p. 4. A government has to legislate to fulfil its political objectives and public policies.4x See Crabbe, 1993, at 1.

Legislation is a form of communication from the government to the people; it “is enacted not, primarily, for those who enact it; it is enacted for the people in a given jurisdiction”.5x See Crabbe, 1993, pp. 5-6. Thus, legislation is like the skeleton of a society. Sometimes, on the one hand, it confers rights, but on the other hand, it seizes rights;6x According to Crabbe, “we need legislation to effect changes in the law; we need legislation to interfere with vested rights and interest”. See Crabbe, 1993, p. 1. it tells the people what to do and what not to do. It provides avenues for dispute settlement and governs new technologies and developments.

Legislation does not appear all of a sudden. According to Tanner, “legislation is the product of many minds and hands well before it comes before a legislature”.7x See G. Tanner, ‘Confronting the Process of Statute-Making’, in R. Bigwood (Eds.), The Statute: Making and Meaning, LexisNexis, Wellington, 2004, p. 54. This means that the government, who normally owns the policies, is not the sole player in making legislation; there are other people or parties that might be involved in the shaping and moulding of the legislation. Basically, the journey of legislation begins with the shaping, moulding and refining of the policies and ends with the passing of legislation by the legislature. There are steps or stages in the process that should ideally be followed in order to come up with a good quality of legislation.

The Thornton’s renowned five-stage drafting process is a widely accepted formula that serves as a guide and rule for the production of good quality legislation. The process not only shows the journey of a bill from the beginning, starting as a plain white paper, but it also emphasizes the importance of every person who is involved in the drafting process.

The efficiency of the drafting process and the main players involved in the process are the two main factors that determine the quality of legislation. As in any production line of factories producing goods, the quality of the product or output is very dependent on the workers who are involved in its production. If the workers do not carry out their tasks efficiently, the quality of the output will certainly be affected. The same reasoning applies to legislative drafting work. Roles and functions of the main players in legislative drafting, such as the policy makers, the public and non-governmental organizations and the drafters, cannot be treated lightly. The whole system might be affected if one of them does not perform his/her role as he/she should, thus rendering the process inefficient, and consequently, the quality of legislation will be compromised.

Lately in Malaysia, there have been occasions when Bills presented before Parliament have to be postponed on the grounds that they failed to take into consideration the interests of the affected parties. The main criticism that has been brought up was that the sponsors of the Bills failed to consult the relevant stakeholders or interested parties when the drafting process was being done. Should consultation have taken place before the Bills were presented, the Bills would not be under such great criticism, which resulted in the postponement. When this happens, it is also very unfair to the drafters who have worked on the Bills day and night to meet the deadline. They believe that all policy matters have been thrashed out with the stakeholders or interested parties before they receive the instructions.

Although it is not something new, consultation has recently been given prominence and emphasis in the drafting process. The importance, value and usefulness of consultation are widely acknowledged. Many jurisdictions in the world have now taken extra measures to foster consultation during the early legislative drafting process. Apart from its existing consultation method, for example the Green and White Papers, the Government of the United Kingdom has recently launched a project called ‘public reading stage’: a type of public consultation that gives the public an avenue to comment on proposed legislation.8x See Cabinet Office of the Government of United Kingdom website <http://publicreadingstage.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/what-is-a-public-reading-stage> (Accessed 27 July 2011). See also Home Office website <www.homeoffice.gov.uk/media-centre/news/parliament-opened-up> (Accessed 27 July 2011). This project aims to improve the consultation, to scrutinize the legislation system and to make better legislation, albeit with the critiques and comments it has invited. In Finland, consultation with stakeholders has been an established part of the Finnish legislative drafting process.9x See Ministry of Justice, Finland’s website <www.om.fi/en/Etusivu/Parempisaantely/Kuuleminen>, (Accessed 27 July 2011). It views consultation as promoting effective drafting and decision making, provided that the consultation is well planned and implemented. In the United Kingdom, the Hansard Society also recognized the importance of consultation in policy development of legislation by “providing a check on whether the proposed measure is technically adequate for its purpose, and whether it might have unforeseen and unacceptable side effects”.10x See Fox & Korris, 2010, p. 53.

With all this importance and the benefits in consultation, the question then arises: what is the contribution of consultation in the drafting process? Does consultation with those stakeholders who are affected or interested parties contribute to the efficiency of the drafting process? Does consultation play any part in determining an efficient drafting process? In view of these questions, therefore, this article aims to examine the influence of consultation in the drafting process in Malaysia. -

B. Hypothesis and Methodology

This article examines and discusses consultation practices during the drafting process and analyses and considers the influence of consultation on the efficiency of the drafting process in Malaysia. The question that has to be answered here is whether consultation has any influence on the efficiency of the drafting process in Malaysia. Does consultation contribute to the efficiency of the drafting process in Malaysia in any way? Acknowledging that there are many factors contributing to and determining the efficiency of the drafting process, I intend to examine the weight and effect of consultation practice in relation to efficient drafting process to see how far it influences the efficiency of the drafting process. The objective is to prove that consultation does have an influence on the efficiency of the drafting process in Malaysia. At the end of this article, I want to show that apart from any other factors affecting and determining the efficiency of the drafting process, consultation does contribute to and influence the efficiency of the drafting process in Malaysia.

To prove my statement, a survey on the drafters in the Drafting Division of the Attorney General’s Chambers was conducted. For that purpose, a survey in the form of a questionnaire was distributed. This method of study was chosen mainly because of the lack of literature and information on the drafting process and its relation to consultation. The respondents were chosen on the basis of their expertise, experience and practical knowledge in the drafting process. They were also the people who were responsible for translating policies into legislation, and in some situations, they were also involved in the policy formulation stage, whether directly or indirectly. Furthermore, the drafting process itself concerns the drafters.11x See V. Vanterpool, ‘A Critical Look at Achieving Quality in Legislation’, 9 European Journal of Law Reform 2007, pp. 167-204, p. 170. Hence, their views and feedback are definitely relevant. The survey questionnaire consists of questions related to the efficiency of the drafting process. All feedback obtained will be analysed and used to prove the hypothesis.

Section C of this article examines the literature on legislative drafting to assess the theoretical basis of the drafting process. The section is defined by, first and foremost, differentiating the drafting process from the legislative process. The drafting process introduced by Thornton is elaborated further. The present drafting process in Malaysia is briefly analysed with a special focus on the peculiarity of the drafting process in Malaysia, namely receiving drafting instructions in the form of a bill. After that, explanations are given on what constitutes an efficient drafting process and the reasons why the process must be efficient.

Section D deals with consultation in the drafting process. The objectives, advantages and disadvantages of consultation are discussed. In this section, a few examples of Malaysian bills that have been withdrawn or criticized heavily for failure to have consultation are discussed in order to show how consultation affects legislation, in particular, and the drafting process, in general.

Section E discusses the relationship between consultation and drafting process by looking at how consultation influences the drafting process and contributes to its efficiency. Section F analyses, assesses and evaluates the findings from the survey questionnaire to support and approve the hypothesis. The last section, Section G, presents the conclusion.

The objective of this study is to analyse and evaluate the current practice of consultation in the drafting process in Malaysia and to assess its influence and contribution to the efficiency of the drafting process. -

C. Drafting Process and Efficient Drafting Process

Once begins the dance of legislation, and you must struggle through its mazes as best you can to its breathless end, – if end there be.12x See Tanner, 2004, p. 53.

Before this article goes any further, it is very crucial to define what is meant by “drafting process” and to differentiate between the “drafting process” and the “legislative process”. To some people, there is no difference between the two terms,13x Biribonwoha defines legislative process “as covering the different procedures from the conception of the need for a law, whether in the form of an amendment or a nascent law, to the time when the conceptualization is crystallized as a gazetted Act of a legislative body of that particular jurisdiction.” See P.P. Biribonwoha, ‘Efficiency of Legislative Process in Uganda’, 7 European Journal of Law Reform 2005, pp. 135-164, at pp. 135-136. but to some, the terms convey distinctive meanings.

According to Thornton, “the process of drafting legislation may be said to begin with the receipt of drafting instructions and end with the completion of an agreed draft”.14x See G.C. Thornton, Legislative Drafting, Tottel Publishing Ltd., Haywards Heath, 1996, p. 124. Thus, the procedures and processes preceding the tabling of Bills in Parliament are referred to as drafting process.15x See Biribonwoha, 2005, p. 136.

On the other hand, legislative process is the passage of legislation through legislature.16x See C. Stefanou, ‘Drafters, Drafting and the Policy Process’, in C. Stefanou & H. Xanthaki (Eds.), Drafting Legislation: A Modern Approach, Ashgate Publishing Ltd., Aldershot, 2008, p. 323. In other words, legislative process refers to “those procedures that a bill goes through in Parliament or legislative body”.17x See Biribonwoha, 2005, p. 136. It is a process embodied in the policy process that has taken place between the formulation stage and the implementation stage.18x See Stefanou, 2008, pp. 322-323 where he states that “The reason for including the stages of the legislative process is very straight forward. As already mentioned most experts refer to the input of drafters in policy-making with reference to the ‘legislative process’. As can be seen in Graph 1, the legislative process is a part of policymaking in the sense that it is part of the policy process located between the formulation stage and the implementation stage. It is, though, by no means the only part of policymaking where drafters are involved.”

In summary, it can be concluded that the ‘drafting process’ and the ‘legislative process’ are two different parts of the whole law-making process and should not be treated as the same. So, for the purpose of this article, ‘drafting process’ is a reference to the procedures and processes of drafting a legislation that take place before the legislation is brought before the Parliament.

Why is it important to have an efficient drafting process? As with any other processes in other fields, drafting process is very important as it provides for “a better means of achieving quality of legislation”.19x See J.G. Kobba, ‘Criticisms of the Legislative Drafting Process and Suggested Reforms in Sierra Leone’, 10 European Journal of Law Reform 2008, pp. 219-249, at p. 219. In legislative work, drafting process seriously affects substance,20x See Tanner,2004, at 49. and it should not be given a light treatment.21x Summers argues that in modern societies, less emphasis has been given to processes than to results. See R.S. Summers, ‘Evaluating and Improving Legal Process – A Plea for “Process Values”’, 60 Cornell Law Review 1974-1975, pp. 1-52, at p. 4. Drafting process is the most important activity in the creation of legislation for its high skills and techniques that it demands.22x See Miers & Page, 1990, p. 57. Thus, the drafting process must be carried out efficiently, given its importance in the substance and quality of legislation.I. Thornton’s Drafting Process

Thornton’s drafting process has been acknowledged and used by drafters as the foundation of their legislative drafting work.23x Vanterpool asserts that “It is noteworthy that this formula has essentially been retained in Thornton’s successive works, and it is this formula which continues even today to form the basis of the structuring of many legislative drafting exercises throughout the Commonwealth. This being the basic formula by which many modern drafters carry out their work.” See Vanterpool,2007, p. 171. Good quality legislation would be produced if a proper and structured process is used as guidance in drafting legislation.24x See Kobba, 2008.

According to Thornton, there are five stages in the drafting process: understanding, analysis, design, composition and development and scrutiny and testing.25x See Thornton, 1996, p. 128. Each of the stages explains steps that should be taken by drafters in composing or drafting legislation. By having this systematic guidance, it is hoped that legislation composed or drafted is of high and good quality. A draft of high and good quality composed by a drafter is crucially important as it is “directly linked to the quality of the future Act”.26x See Fox & Korris, 2010, p. 86.

For a drafter, the first stage is to understand the legislative proposal received from the sponsor. At this stage, it is very important for the drafter to understand what the proposal is all about “as the quality of the output is directly related to the quality of the input at this stage”.27x See Vanterpool, 2007, p. 173. A drafter who thoroughly understands a proposal would then have a clear picture of what is intended by it, thereby facilitating the drafting exercise. Without such an understanding, it would be difficult for the drafter to transform the policy instruction into a legislative form. At this stage, a lot of reading, scanning and examining have to be done by the drafter in order to fully comprehend the proposal.28x Thornton states this stage requires a lot of patience, time and great care and a drafter might have to work hard to completely and accurately understand the goals of a proposal. See Thornton, above note 14, at 129. See also Kobba, 2008, p. 227; Vanterpool, 2011, p. 172. There are two main things that might contribute to and enhance the drafter’s understanding of the proposal, that is, clear and precise drafting instructions and discussion and consultation with the instructing officer.29x See Thornton, 1996, p. 129. Vanterpool, however, adds an extra element that could help a drafter in understanding a proposal. He argues that in order to have a sound understanding of a proposal, a drafter should at times get involved in matters of policy. See Vanterpool, 2011, p. 173. Good drafting instructions are written straightforwardly with jargon-less, clear and plain language and in narrative forms, not in the form of a bill.30x Thornton asserts that “Good instructions are a pearl beyond price and not only improve the quality of the Bill but also reduce drafting time. Bad instructions are the bane of the drafter’s life.” See Thornton, 1996, p. 129. An early discussion or consultation with the instructing officer enables the drafter to call for further explanation on unclear matters, especially when the proposal involves complex, problematic and technical matters.31x See Thornton, 1996, p. 132. See also Kobba, 2008, p. 230.

The second stage is analysis of the legislative proposal.32x According to Thornton, the analysis to be made is in relation to existing law, special responsibility area and practicality. See Thornton, 1996, p. 133. At this stage, the drafter is expected to study and examine how the proposal affects the current legal framework of society, especially existing laws including common laws. This analysis is vital because of the fear of repeating, clashing or contradicting the existing laws. By having the proposal analysed at this very beginning stage, the drafter would have a chance to assess the correctness and implications of the proposal and alert the instructing officer about it. Thus, policy modification and refinement can be done. As Thornton rightly points out, although policy matters of legislative proposals are not the concern of the drafter, owing to the drafter’s position, however, the drafter is responsible to ensure that the proposal complies with the basic principles of the legal and constitutional system, especially when it comes to special or danger areas.33x Thornton points out some danger areas that a proposal might affect, e.g. personal rights, private and property rights and international obligations and standards. See Thornton, 1996, pp. 133-138. Furthermore, by carefully analysing the proposal, the practicality and enforceability of the legislative proposal could be assessed and considered. Consequently, the analysis would reveal whether or not the objectives of the proposal are best attained through legislation of this kind.34x See Vanterpool, 2011, p. 178.

The next stage is designing or planning. This stage is about designing and planning the structure of the proposed legislation. In other words, this is the stage where a drafter shapes the framework of the proposed legislation by determining the form of legislation that should be introduced, the clauses that should be provided in the proposed legislation, including their logical sequence and so forth.35x According to Thornton, by designing the structure of proposed legislation, it helps the drafter to consider the material as a whole and to assess the relative importance of topic, to link all related elements in mind and to see the best way to present all the material. See Thornton, 1996, p. 138; see also Kobba, 2008, pp. 236-239; K. Patchett, ‘Preparation, Drafting and Management of Legislative Projects’ (a paper presented at the Workshop on the Development of Legislative Drafting for Arab Parliaments, 3-6 February 2003, Beirut. Copy of paper is available online at <www.undp-pogar.org/publications/legislature/legdraft/kpe.pdf>), paras 41-44. (Accessed 23 July 2011). By designing an initial framework before the actual drafting exercise starts, the drafter can visualize the whole concept of the proposed legislation and can use it as a checklist for composing the actual draft.36x Ibid. At this point of time, discussion and communication with the instructing officer about any issues that are relevant or what should or should not be in the proposed legislation would be useful as the drafter could outline the design effectively.37x See Kobba, 2008, pp. 236-239.

After having designed a skeleton or initial structure of the proposed legislation, the next thing to do is to compose or draft the actual provisions, clause by clause, to effect and respond to the policies required. At this stage, the skills and abilities of a drafter are actually tested and challenged. While complying and adhering to the conventional drafting practice, and local language and grammar are emphasized,38x See Thornton, 1996, p. 144. the drafter should also compose the draft plainly, precisely and accurately, so as to ensure the effectiveness of the legislation produced.39x Patchett lists some of the principles of legislative composition, such as avoiding long sentences and using terminology consistently. See Patchett, 2003, at para. 45. Discussions and deliberation with the instructing officer over draft legislation at this stage is important as not only is the officer able to point out any inaccuracy or inadequacy of the draft, but also the drafter is able to discover any loopholes or defects in the policies.40x See Kobba, 2008, p. 240.

The fifth stage is scrutiny and testing of the draft. At this stage, the final draft composed by the drafter is subject to verification and testing, to ensure it reflects and manifests the policies and objectives to be achieved. In the process of composing and developing, some errors might occur: some critical points might be overlooked or some provisions might contradict each other. All of these incidents are expected to occur as in the process of composing, the draft is subject to several amendments owing to constant refinement or policy modification.41x See Miers & Page, 1990, p. 64. Although the drafter himself has scrutinized his draft during the composing and developing stage, having a fresh pair of eyes looking at the final draft is advisable as it serves as a double-checking system.42x In some countries, draft legislation must be submitted to an administrative tribunal for review. See Patchett, 2003, at para. 48. The draft is then subjected to revision and amendment when consultation between the instructing officer with the drafter on one side and any interested or affected parties on the other side takes place.43x See Kobba, 2008, p. 241. See also Thornton, 1996, p. 173.

Having discussed all stages of the drafting process laid down by Thornton, it can be concluded that there are two important aspects of the drafting process: the relationship between the drafter and the instructing officer and the actual drafting of legislation. The relationship between the instructing officer and the drafter is not confined to the first stage only. Communication between the instructing officer and the drafter throughout the drafting process is crucial as they are dependent on each other. The instructing officer needs the drafter to help in transforming the policy into legislative text, and the drafter needs the instructing officer to provide him/her with sufficient, clear, accurate and precise instructions. Thus, the critical or vital element governing their relationship is ‘drafting instructions’. No relationship in the first place exists between them without such instructions. Discussion, deliberation and communication between them exist for the purpose of clarification and further explanation of such instructions. Hence, drafting instructions play a major part in the drafting process, and therefore, they must be good drafting instructions. What is meant by good drafting instructions is that the instructions must be complete, precise, accurate, comprehensible and must take into account all necessary points and issues pertaining to the legislative proposal.44x St.J. Bates argues that an ideal instruction is an instruction that contains “a clear detailed account of the policy which is to be implemented by the legislation, existing legislation which relates to this and similarly any relevant judicial decisions”. See T.St.J.N. Bates, ‘Legislative Drafting in the United Kingdom’ (a workshop paper presented in Different Approaches to Legislative Drafting in the EU Member States Workshop on 14 December 2009. Copy available online at <www.oecd.org/dataoecd/58/49/44577527.pdf>). But, in reality, most of the times the instruction received is incomplete and comes in chunks, especially when a certain deadline is to be met. A good instruction is the one that is well-thought. See observation by E.C. Page, ‘Their Word Is Law: Parliamentary Counsel and Creative Policy Analysis’, 2009 Public Law, October, pp. 790-811. Good drafting instructions can be obtained only through a well-developed and well-prepared policy at the policy formulation stage – the stage before the drafting process starts. Hence, it can be said that the policy formulation stage could affect the drafting process; it is either facilitating the process or delaying the process. Unless the instructions are clear on the idea and objectives of the proposal, “it is sheer waste of time to embark upon drafting a piece of legislation”.45x See Crabbe, 1993, p. 14. To start drafting a piece of legislation, the drafter must understand the concept behind the proposed legislation, or otherwise the drafter would ‘produce garbage’.46x See Page, 2009, p. 801. Thus, the policy formulation stage and drafting instructions seem to have a big influence on the efficiency of the drafting process.47x Biribonwoha argues that the efficiency of the first stage of the drafting process (in relation to instructing the drafter) is very much dependent on the efficiency with which the instruction is made. See Biribonwoha, 2005, p. 145.II. Malaysian Drafting Process

As in many other countries, the vast majority of statutes introduced in Malaysia is by the Government (in fact, until today, no private bill has been successfully introduced in Parliament).48x In order to be able to govern the affairs of the country and society, a Government must be able to legislate. As the body to which the executive authority is entrusted, the Government recommends to the legislature any policy and measure it should adopt and having it supported by legislation. See Miers & Page, 1990, p. 6. As a matter of fact, legislation has been greatly influenced by politics. As Tanner puts it, “Legislating is not a clinical process. It is intensely political. Politics plays a major part in determining what legislation is enacted, when it is enacted, and the substance of it when it is enacted. Legislation reflects policy choices. Those choices are overtly influenced by political, economic, and moral philosophies.” See Tanner, 2004, p. 52. When a Ministry proposes to come up with a Bill, it must first obtain the approval of the Cabinet. To do that, the Ministry will submit a memorandum to the cabinet explaining and defending the need for the Bill. When the approval is obtained, a detailed legislative proposal is prepared. The policy that underpins the proposal will be formulated and refined by holding discussion and consultation with any interested or affected parties, such as other governmental departments or agencies, experts or non-governmental organizations. After having a number of intense discussions and deliberations on the proposal, the Ministry officials will prepare drafting instructions to be submitted to the Parliamentary Draftsman.

Although many drafters in other countries reject drafting instructions in the form of a draft Bill, it is not the case in Malaysia. Drafting instructions that have to be submitted to the Parliamentary Draftsman must be in the form of a draft Bill. The English common law practice demands that drafting instructions be written in narrative style, rather than in the form of a draft Bill. In Malaysia, however, drafting instructions must be in the form of a draft Bill. Many opinions have been voiced on the advantages or disadvantages of having drafting instructions in the form of a draft Bill.49x See I. McLeod, Principles of Legislative and Regulatory Drafting, Hart Publishing, Oxford, 2009, p. 38.

According to Stark,50x See J. Stark, The Art of the Statute, F.B. Rothman, Littleton, CO, 1996, p. 19. receiving drafting instructions in the form of a draft Bill is considered unlucky for some reasons, such as the absence of intent statement. The drafter has to study the draft Bill clause by clause, trying to penetrate and figure out what it is all about and to assume the intention of the instructing officer towards the draft Bill.51x See Thornton, 1996, p. 129. See also E.A. Driedger, The Composition of Legislation (2nd edn), Department of Justice, Ottawa, 1957, pp. xix-xx. Drafting instructions in narrative form are more clear and straightforward as to what the problems that give rise to the proposed Bill are, the intention of the Bill and the aims and objectives the Bill is trying to achieve.52x Ibid. Ideally, drafting instructions would contain background information, the purpose of the proposed legislation and the means to achieve it and the impact on existing circumstances and law.53x See Thornton, 1996, p. 130.

When receiving the draft Bill, the Parliamentary Draftsman will assign the drafters responsible for the draft Bill, and usually a pair of drafters is assigned for one Bill. The drafting process will then begin. It is worth mentioning that every draft that has been vetted by the responsible drafter must be submitted to the Parliamentary Draftsman or the Deputy Parliamentary Draftsman for approval. The approved draft will then have to be submitted to the Solicitor General for second final approval. This is to ensure that the final product is “constitutionally and legally sound and error-free in every aspect”.54x Client’s Charter of the Drafting Division, <www.agc.gov.my/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=50&Itemid=112&lang=en> (Accessed 26 July 2011).III. Efficient Drafting Process

What is efficient drafting process? What constitutes efficiency in drafting process? The critical point that has to be sorted out before proceeding with this article is what would be the criteria for measuring and evaluating the efficiency of the drafting process?

While there is considerable literature that discusses the efficiency of legislation and legislative process, this is not the case for drafting process. There is no specific literature discussing the efficiency of drafting process. Owing to the lack of studies on efficiency of the drafting process, it is important to establish the criteria that can be used and applied in assessing and evaluating efficiency of the drafting process.

To do this, I will refer to the literature on efficiency in other fields, particularly efficiency of management in the public sector and efficiency of policy formation. These two fields are mainly chosen and analogized because to me, the drafting process is about service rendered by the public sector, and the drafting exercise itself involves policy formulation and development. The Drafting Division is attached to the Attorney General’s Chamber, the office under the Prime Minister’s Department, which is considered part of the public sector. The drafting job undertaken by the Drafting Division is a combination of policy and legal matters. Drafting process starts with the moulding and shaping of policies by the ministries’ officials. Although policy formulation and development should ideally be dealt with by the ministries officials, in most cases, these policies would be polished and refined during the drafting of legislation.

From the literature references, I will examine and analyse the given interpretation of efficiency and utilize the criteria of efficiency to drafting process.

Efficiency is one of the higher values promoted in legislative drafting.55x See H. Xanthaki, ‘On Transferability of Legislative Solutions: The Functionality Test’, in C. Stefanou & H. Xanthaki (Eds.), Drafting Legislation: A Modern Approach, Ashgate Publishing Ltd., Aldershot, 2008, p. 4. The Concise Oxford English Dictionary56x Concise Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2005. defines efficient as ‘working productively with minimum wasted effort or expense’ and efficiency as ‘the state or quality of being efficient’. According to Pius,57x See Biribonwoha, 2005, p. 138. efficiency reflects “the extent to which perceived best practices are utilised in the process of the development of legislation”. Best practice is “finding and using the best ways of working to achieve your business objectives”.58x Business Link website <www.businesslink.gov.uk/bdotg/action/detail?itemId=1074450434&type=RESOURCES> (Accessed 16 June 2011).

In their book, Efficacy and Efficiency in Multilateral Policy Formation,59x See R.Th. Jurrjens & J. Sizoo, Efficacy and Efficiency in Multilateral Policy Formation: The Experience of Three Arms Control Negotiations: Geneva, Stockholm, Vienna, Kluwer Law International, London, 1997, p. 372. Jurrjens and Sizoo said that “efficiency of a given means is determined by its ability to reach a given end at the lowest possible costs in terms of financial and human resources, time or the risk of failure”. Lon Roberts60x L. Roberts, Process Reengineering: The Key to Achieving Breakthrough Success, ASQC Quality Press, Milwaukee, WS, 1994, p. 19. defined efficiency as “the degree of economy with which the process consumes resources – especially time and money”.

It is also called efficiency when a desired outcome is made with minimum “energy, time, money, materials, or other costly inputs”.61x G. van der Waldt, Managing Performance in the Public Sector: Concepts, Considerations and Challenges, Juta and Co. Ltd., Landsdowne, 2004, p. 70. In other words, “efficiency is the measure of the speed and accuracy with which work is completed”.62x Ibid., p. 71. In relation to human action, “efficiency involves the adoption of the means most suited to securing a particular end, without reference to sacrifice of other ends (cost) and without any restriction on the selection of means except that of intrinsic relationship to the end”.63x W.E. Moore, Industrial Relations and the Social Order, Arno Press, New York, 1977, p. 185.Table 1 Elements of EfficiencyTable 1 is a summary of the elements of efficiency discussed above. As can be seen from the table, efficiency is when cost and failure are minimized, producing a quick and accurate output. In terms of cost, it is not only related to monetary or financial aspects, butis also connected to time and human resources.Elements of Efficiency Concise Oxford English Dictionary Productive

Minimum wasted effort

Minimum wasted expense

Pius Utilization of best practices

Jurrjens and Sizoo Lowest possible costs in terms of: financial resources

human resources

time

risk of failure

Waldt Minimum energy, time, money, materials, or other costly inputs

Speed and accuracy

Moore Suitable means

No sacrifice of cost

No restriction on the selection of means (except of no value to the end)

Therefore, the drafting process is efficient when a quality bill is produced with minimum risk of failure incurring minimal financial and human cost. Thus, wasted time, costs and effort can be reduced. An efficient drafting process also means that the bill will eventually progress with speed without any interruption or delay. But this does not mean getting it done quickly. Hence, for the purpose of this article, efficiency of drafting process is determined when:wasted financial cost is minimized;

wasted human resources or effort is minimized;

wasted time is minimized;

risk of failure is minimized; and

progress is unobstructed or there is no delay (‘clear-sailing’).

-

D. Consultation: What and Why?

Additionally, there is widespread criticism that the quality of policy preparation and public consultation by departments – particularly the involvement of experts with specialist knowledge that could usefully be deployed in the policy development process – is inadequate and weak.64x See Fox & Korris, 2010, p. 13.

What is the foundation of good legislation? The answer is that there is no specific answer to that question. The foundation of good legislation can be varied. But one of the foundations of good legislation is “sound policy development and policy decision making”.65x See Tanner, 2004, p. 58.

The manner in which the policy is developed and prepared not only has an impact on legislation but also has a direct effect on the overall drafting process. Why is it so? The reason is that policy and drafting process are so intimately related that they are inseparable. The drafting process is a process by which a policy is translated or reduced into legislative language, and unless and until the policy is clear and adequate, the drafting process would not go smoothly and efficiently.66x See Crabbe, 1993, p. 14.

What determines ‘sound policy development and policy decision making’? In other words, what goes into a policy well and soundly made? What should the instructing officers or departments do in order to make the policy being developed effective and of quality so as to ensure that the policy is beautifully shaped and refined?

According to Staronova and Matheronova,67x See K. Staronova & K. Matheronova, ‘Recommendations for the Improvement of Policy Making Process in Slovakia’, at 9. (A Policy Paper under the International Policy Fellowships. Copy available online at <www.policy.hu/staronova/FinalPolicyPaper.pdf>) (Accessed 1 August 2011). a quality policy process can be achieved by, inter alia, fuller use of consultation with the public and affected groups. In suggesting the best practice in policy formulation, Patchett stresses the importance of consultation in the policy-making process,which, although consultation comes at a price, if effectively conducted, would bring benefits and become useful.68x See Patchett, 2003, paras 18-22. The Merits of Statutory Instruments Committee in the House of Lords has made it clear by saying that “analysis of the results of consultation is vital for good policy making and proper scrutiny”.69x See Fox & Korris, 2010, p. 62.

Thus, one of the ways to have a good policy development and decision making process is by having consultation during the process. Consultation is about “gathering of views, information and experiences of the stakeholders about the matter that is being prepared”.70x See Ministry of Justice, Finland’s website, supra note 9. Inasmuch as the root of a legislative proposal is to overcome a public policy issue, it is befitting for stakeholders or affected parties to have their views and opinions heard through consultation.71x See Biribonwoha, 2005, p. 136. See also C. Kyokunda, ‘Parliamentary Legislative Procedure in Uganda’, 31 Commonwealth Law Bulletin 2005, pp. 17-27, at 17, where she states, “… the fact that legislation affects every individual in the jurisdiction in which it operates, makes it important for all persons involved in its making to appreciate not only the law, but also the process so as to effectively participate in that process and make meaningful contributions”. The views and information from the stakeholders, especially the experts and affected parties, are valuable and useful as they know the shortcomings or potential consequences of the legislative proposals.72x The Ministry of Justice, Finland, also shares this view by stating that “The goals of consultation are openness and high quality of statute drafting. Consultation aims at finding out the different views, impacts and opportunities for practical implementation relating to the matter being prepared. With the help of consultation, the trust in statutes and in the democratic decision-making are also improved. When consultation is conducted, the aim is that the key stakeholders participate in the drafting process or that their views are otherwise heard to a necessary extent during the drafting process. In the consultation, open and constructive interaction between the drafters and the stakeholders is pursued.” See Ministry of Justice, Finland’s website, supra note 9. Just as important, consultation shows good governance of the government. Good governance of a government takes into account non-arbitrary decision making, which means making the government business conducted openly and allowing persons affected by its decision to take part or participate in governmental decisions.73x See Seidman, Seidman & Abeyesekere, 2001, p. 8. Biribonwoha also shares the same idea on good governance by saying that public consultation is one of the demands of good governance; especially in as far as it is regarded as an example of public accountability. See Biribonwoha, 2005, p. 144. Eventually, the acceptance of the people and the credibility and legitimacy of the government’s action can be improved.74x See Legislation Advisory Committee of New Zealand Guidelines (LAC Guidelines) (2001 edn, as amended), para. 1.4.2, as quoted in J.F. Burrows, Statute Law in New Zealand (3rd edn), LexisNexis, Wellington, 2003, p. 64. Without such participation, the government would be seen as “a rigid and ignorant tyranny” and public administration as “a rigid and stupid bureaucracy”.75x See J.P. Mackintosh, The British Cabinet (3rd edn), Stevens and Sons, London, 1977, p. 578 as quoted in Miers & Page, 1990, p. 41. The objectives of consultation, to involve the public in government decision-making process, are best summarized by Walters, Aydelotte and Miller as follows:discovery: a search for definitions, alternatives, or criteria;

education: to inform and educate the public about an issue and proposed alternatives;

measurement: to assess public opinion on a set of options;

persuasion: to persuade the public towards a preferred option;

legitimization: to comply with public norms or legal requirements.76x See L.C. Walters, J. Aydelotte & J. Miller, ‘Putting More Public in Policy Analysis’, Public Administration Review, Vol. 60, No. 4, 2002, pp. 349-359, at 352 as quoted in Fox & Korris, 2010, p. 56.

Although there are differing opinions and views about the value of consultation, some commentators are rightly stating the advantages or benefits of consultation. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has summarized the benefits that can be obtained if consultation on legislative proposal is done during the law-making process.77x Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), ‘Law Drafting and Regulatory Management in Central and Eastern Europe’, SIGMA Papers No. 18, at 19. See <www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=OCDE/GD%2897%29176&docLanguage=En> (Accessed 6 August 2011). According to the OECD, by holding consultation, not only can the range of policy proposal be widened, but the opportunities to collect the necessary data and information and to verify the results of analysis are present as well. This may result in more informed choices with regard to the legislative solutions that give effect to the policy. Consultation can also be a means of explaining to the people the problems to be solved and the activities to be regulated, thus ensuring better understanding of the issues in hand. Consequently, this would make the policy and the law-making process more transparent, and the government would be seen to be more responsive to the interests of affected parties. Eventually, all of these would encourage compliance with legal solutions and would improve the communication of legal requirements.

Miers and Page view the benefits of consultation from two different angles, namely from the government’s perspective and the stakeholders’ perspective.78x See Miers & Page, 1990, p. 41. If consultation is carried out, the government’s policy would be finely formulated with the expertise, skills and experience of the stakeholders, resulting in a highly workable policy. The involvement of the stakeholders, whether passive or active, would ensure the acceptance and acquiescence of the stakeholders of the proposed legislative action. As another point of view, stakeholders involved in the policy formulation would feel appreciated as they have the opportunity to channel their views and opinions on the matters being discussed.

It is commonplace for many jurisdictions, including Malaysia, to carry out consultation with other government departments or agencies when legislative proposals impact on the jurisdictions or responsibilities of the departments or agencies. The purpose of holding or carrying out consultation within government departments or agencies is to make sure that the interests of the government are taken into account comprehensively and that the stands of the departments or agencies on the proposed subject matter do not contradict each other. This is, however, not the case for agencies or parties outside the government. Consultation with those agencies or parties takes place at the discretion of the government.79x See Miers & Page, 1990, p. 40. See also M. Zander, The Law-Making Process (6th edn), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004, p. 8. This means that the government can choose whether to consult or not to consult, or whom to consult or not consult, or to what extent the consultation should be made. Having mentioned the benefits of consultation above, the question that arises is, why does this happen? Why does the government, in some cases (or perhaps in all cases), seem to be reluctant to have its legislative proposals open for consultation?

Among the critiques of consultation is the time constraint. It is claimed that consultation takes up a great deal of time and would thus slow down the policy-making process.80x See Biribonwoha, 2005, p. 142; Burrows, 2003, p. 64; Patchett, 2003, at para. 18. Further, when a bill is needed urgently, it is more unlikely that the government would allow consultation as this would consume a lot of time and prolong the drafting process. Apart from that, it is the government’s belief that ‘government knows best’ and the government hesitates to disclose its policy before it has been given final shape.81x See Patchett, 2003, at para. 18. It is also argued that the views and opinions of the stakeholders or the public be channelled through Parliament when legislation has been tabled.82x Zander says that “The traditional Whitehall view was that outside persons and bodies should not normally be consulted at this stage – that the time for consultation is later when the bill has been introduced in Parliament.” See Zander, 2004, p. 8. But in a system where there is no pre-legislative scrutiny, including Malaysia, this view is not really applicable. Although a bill may be referred to a special select committee through normal legislative process of Parliament, this is subject to a motion approved by the House where in most cases, this motion be always rejected by the overwhelming majority of government members. Moreover, the genuine views and opinions of the stakeholders on matters being discussed are doubted because the real objectives of the stakeholders are difficult to determine,83x Ibid. for they represent and plead arguments and opinions in favour of their interests, resulting in the interests of other parties being ignored.84x See Miers & Page, 1990, p. 41. Furthermore, consultation is regarded as an expensive exercise.85x See Biribonwoha, 2005, p. 143.

Having mentioned the reasons above, we can see that arguments on both the advantages and the disadvantages of consultation are valid. On the one hand, consultation is seen as a quality contributory factor in the formulation and refinement of policy, thus assuring the quality of the legislation produced. On the other hand, it is regarded as an encumbrance and a burden to the government. As rightly stated by Ash:Some civil servants may see consultation as an undesirable delay in the difficult business of establishing policy; an unwelcome intrusion into the purview of an elected government that consumes resources without product. From the NGO perspective, consultation may appear a perfunctory exercise designed to lend a cloak of respectability to an unrepresentative decision process dominated by the few. In fact, while public consultation is a matter of degree, all stakeholders stand to benefit, although not always in a direct manner.86x See article by J. Ash, ‘Greenpeace v. DTI: Courts May Also Have Their Say in Nuclear Development’, March 2007. Copy available online at <www.energypolicyblog.com/2007/03/22/greenpeace-v-dti-courts-may-also-have-their-say-in-nuclear-development/> (Accessed 1 August 2011).

The conflict between the demands of the stakeholders and the interests of the government in a consultation issue is not unknown to many jurisdictions. Under the pressure of time and commitment, it is agreed that it is impossible for the government to satisfy the interests of every single individual. But this does not mean that the government can totally ignore any view or opinion of the people, especially the affected and minority parties. In this regard, the thoughts of Redlich are worth mentioning:

Failure of the government to conduct consultation may bring court actions against it. Although this case never happens in Malaysia, it did happen in the United Kingdom.88x See Fox & Korris, 2010, p. 59. The value and significance of consultation has recently been endorsed by the United Kingdom’s court through the Greenpeace case.89x See R (Greenpeace Ltd) v. Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, [2007] EWHC (Admin) 311. In this case, the government’s failure to conduct ‘the fullest public consultation’ was held to be ‘very seriously flawed’. This successful challenge by the Greenpeace has proved that a flawed consultation exercise, that is, an inadequate and incomplete exercise, would deprive the stakeholders of the chance to give their ‘intelligent response’.The majority holds the great advantage of being able to realise its wishes in the institutions of government; but, on the other hand, for this very reason the minority ought to have all conceivable rights of expressing its views and aims, …87x See Redlich, The Procedure of the House of Commons, 1908, Vol. 1, at 131, as quoted in Miers & Page, 1990, p. 73.

In Malaysia, the importance of opinion from the public or stakeholders in the output of the drafting process was recently evident when several bills presented before the Parliament were criticized because of the government’s failure to take into consideration views and opinions from the public, especially the stakeholders and experts. In some cases, bills were postponed for policy review and refinement.

The recent bill passed by the Parliament, the National Wages Consultative Council Bill 2011, was condemned for not giving a chance to two major stakeholders, the Malaysian Trade Union Congress (the MTUC) and the Malaysian Employers’ Federation (the MEF), to give their views and objections. They claimed that they were not invited and consulted about the Bill. Inasmuch as the passed law does not fulfil the interests of employers and employees as a whole, the MTUC and the MEF were reported to demand that the Government make amendments to the law.90x See Hansard dated 30 June 2011. Copy available at the Malaysian Parliament website <www.parlimen.gov.my/files/hindex/pdf/DR-30062011.pdf> (Accessed 18 August 2011). See also an article by G. Manimaran, ‘MTUC, MEF Say No to New Minimum Wage Bill’, The Malaysian Insider, 2011, at <www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/mtuc-mef-say-no-to-new-minimum-wage-bill/> (Accessed 18 August 2011). This was not the first time the MTUC and the MEF claimed that they were not consulted about proposed laws concerning their speciality and interest. In 2007, they opposed the Industrial Relations (Amendment) Bill 2007 and the Trade Union (Amendment) Bill 2007. Both Bills had raised an outcry among the employers and employees when the provisions were claimed to be unconstitutional and that they did not bring any benefits to the employees. The MTUC claimed that the Minister gave the impression that the MTUC was consulted, when in fact no consultation had been made by the Ministry regarding the amendments.91x See Hansard dated 27 and 28 August 2007. Softcopy version is not available at the Malaysian Parliament website.

Another instance where a bill was postponed owing to objection and resistance from the public, especially stakeholders, was the Goods and Services Tax Bill 2009. When this Bill was tabled in Parliament for the first reading on December 2009, it generated much public interest and outcry. The Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers was of the view that Malaysia was not ready for a goods and services tax and that the proposed Bill should be deferred.92x See Bernama, ‘FMM Says Malaysia Not Ready for GST, Suggest Retail Sales Tax’, Bernama, Malaysia, 9 March 2010, <http://kpdnkk.bernama.com/news.php?id=481112&vo=30> (Accessed 18 August 2011. Later, in March 2010, the Government decided to postpone the second and third readings of the Bill so as to enable the Government to collect opinions and views of the public.93x See Hansard dated 16 March 2010. Copy available at the Malaysian Parliament website <www.parlimen.gov.my/files/hindex/pdf/DR-16032010.pdf> (Accessed 18 August 2011).

The same happened to the Road Transport (Amendment) Bill 2010. Not only did the public protest loudly when the Bill was introduced for the first reading, but the government backbenchers were also opposing the proposed amendment. Acknowledging the fact that the Bill was a burden to the people and would likely cause injustice to them, the Minister withdrew the Bill from the relevant government agency to refine the policy behind the proposed amendment so as to ensure that the amendment was ‘people-friendly’.94x See ‘Road Transport Act Amendments Put Off’, New Strait Times, Malaysia, 22 April 2010, <www.bnbbc.com.my/bi/news.php?act=view&berita_id=131> (Accessed 19 August 2011). Consultation with the public, public authority and legal experts was suggested in order to learn their views and opinions.95x See Bernama, ‘Kerajaan Tarik Balik Rang Undang-Undang Pengangkutan Jalan (Pindaan) 2010’, Berita Harian, Malaysia, 21 April 2010, <www.bharian.com.my/bharian/articles/KerajaantarikbalikRangUndang-UndangPengangkutanJalan_Pindaan_2010/Article> (Accessed 19 August 2011).

All the above instances show that lack of consultation brought severe criticism for bills that were produced and made their passage difficult. All efforts invested and time spent drafting the bills were also in vain when the bills had to be withdrawn or postponed. If consultation had taken place before or during the drafting process, the possibility of the proposed bills being deferred owing to failure to consider public interests and opinions would have been avoided. This was evident in the drafting of the Wildlife Conservation Bill 2010. Although another consultation and meeting with the stakeholder (the World Wildlife Foundation, Malaysia, “the WWF”) had been held after the first reading of the Bill, at least the views and opinions of the WWF, regarded as experts and of high interest, could have been taken into account before the second and third readings. In this case, a few suggestions from the WWF were accepted by the Ministry, and amendment in committee was subsequently made to the Bill during the second reading.96x See Hansard dated 13 July 2010 p. 97. Copy available at the Malaysian Parliament website <www.parlimen.gov.my/files/hindex/pdf/DR-13072010.pdf> (Accessed 20 August 2011). The advantages of doing this were that, firstly, it helped smooth and clear the passage of the Bill in Parliament, and that, secondly, it could avoid subsequent amendment to the Bill later on.

The above discussion of the importance of consultation and its good and bad consequences makes it clear to us that consultation is at the government’s discretion; thus any recommendation or opinion does not necessarily have to be accepted by the government. The government is at liberty whether or not to accept it. But when the government has made a promise to carry out consultation, then the government must honour its promise, as rightly stated by learned Law LJ in the case of R (Nadarajah and Abdi) v. Secretary of State for the Home Department:97x [2005] EWCA Civ 1363, para 68.Where a public authority has issued a promise or adopted a practice which represents how it proposes to act in a given area, the law will require the promise or practice to be honoured unless there is good reason not to do so.

To me, consultation is a good practice to be applied in the drafting process as it would gather opinions from the public and experts. Good consultation is about “asking the right people the right questions at the right time”.98x See Fox & Korris, 2010, p. 57. It requires both parties, the government and the parties consulted, to genuinely participate in the consultation process with a view to fine-tuning and polishing the policies so that good quality laws could be produced. The only thing hindrance to good and effective consultation is the negative perception that has been set in the minds of both the government and the parties consulted. It is a great mistake for the parties consulted to presume that whatever opinions and views they give must be taken into account by the government. This type of false expectation makes the government feel displeased and choose not to hold consultation. On the other hand, when the intention of the government carrying out consultation is just to legitimize its proposal while the policy has been finalized and made up or the consultation is just a formality, it can become a total offence to the parties consulted when they think that the government is not genuine and does not need their opinions.99x Ibid., pp. 58-59.

Thus, this predicament can be overcome only when the government and the parties consulted are ready to give and take for policy betterment. The outcome of a consultation should drive policy, not be an afterthought.100x See House of Lords Merits of Statutory Instruments Committee (2007-08), The Management of Secondary Legislation: Follow-Up, HL70, at 7 as quoted in Fox & Korris, 2010, p. 62. -

E. Consultation and Drafting Process: The Relationship

If the legislative processes are to work efficiently, the work of profesional drafters will have to be supplemented by a cadre of public officials who fully understand their role in the legislative process and play it adequately.101x See B.H. Simamba, ‘Improving Legislative Drafting Capacity’, 28 Commonwealth Law Bulletin 2002, p. 1125, pp. 1129-1130.

In the previous sections, I have discussed both the drafting process, together with its role in guiding drafters to produce high-quality legislation efficiently, and also consultation – its importance, advantages and disadvantages. In this section, the discussion is centred on the relationship between consultation and the drafting process as well as the influence of consultation on the efficiency of the drafting process.

I. How Consultation Relates to Drafting Process?

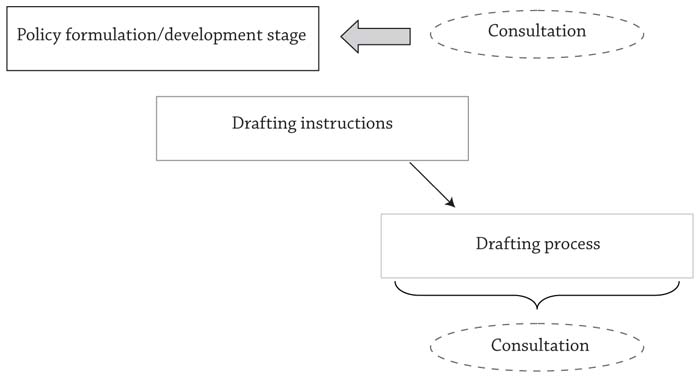

Figure 1 Relationships between Drafting Process and Consultation

Figure 1 Relationships between Drafting Process and ConsultationHow does consultation relate to the drafting process? In my opinion, consultation relates to or affects the drafting process in two ways: first through drafting instructions and secondly during the drafting process.

Drafting process is a process whereby government policies are converted into enforceable laws. As mentioned earlier, the drafting process begins with the receipt of drafting instructions from an instructing officer. Without such instructions, no drafting will take place. Therefore, it can be said that drafting instructions are the important element that relates a drafter and an instructing officer. In Section C, we have already discussed that the relationship between a drafter and an instructing officer is pivoted mainly on drafting instructions. Drafting instructions are one of the main ingredients in the law-making process. The importance of good drafting instructions cannot be denied, and, as Thornton puts it,

Therefore, good and effective drafting instructions are significant and valuable in the drafting process. Drafting instructions are the outcome of policy formulation and development at the very early stage of legislative drafting. As stated earlier, a good and sound policy formulation and development does take into account views, opinions and feedback from the public, especially stakeholders and those affected by the legislative proposal. Views, opinions and feedback can only be effectively obtained by carrying out consultation.Good instructions are a pearl beyond price and not only improve quality of the bill but also reduce drafting time.102x See Thornton, 1996, p. 129.

Hence, as we can see from Figure 1, if consultation is carried out at the policy formulation stage, views, opinions and feedback from the public can be gathered and formed as parts of the policy. Consequently, fine-tuned and polished policy that has taken into account the views, opinions and feedback will then be transformed into drafting instructions. These drafting instructions are those given to drafters, to be translated into legally sound legislation. Therefore, it can be said that through drafting instructions, consultation indirectly relates and affects the drafting process. In other words, consultation affects drafting instruction, and drafting instruction affects the drafting process.

Therefore, we can suggest that ideally, consultation is best done during the policy formulation and development stage. By having consultation as early as at the policy formulation and development stage, it would eliminate problems concerning a legislative proposal, and would thus give a clearer guidance to drafters as to the objectives and purposes of the policy behind the legislative proposal.103x Fox & Korris opine that ideally, consultation should be done as early as at the policy formulation and development stage. This practice is recommended as it would give drafters a clear picture of the aims and objectives of legislative proposals when receiving drafting instructions. Additionally, the more problems settled early on, the smoother the law’s passage should be. See Fox & Korris, 2010, p. 45. Clear and resolved policy guidance would definitely be useful to drafters as this would make their job go smoothly with minimal problems and difficulties. Consequently, this would contribute to the efficiency of the drafting process.

The importance of having an effective policy-making process is thus obvious in ensuring the overall drafting process works smoothly. This is because the policy moulds the shape and substance of the instructions that drafters heavily relied upon in drafting legislation. Consequently, bad drafting instructions owing to an improper or ineffective policy-making process affect the drafting process adversely, thus making the drafting process inefficient.

The second scenario in which consultation relates to the drafting process is when consultation is carried out during the drafting process. Obviously, this is a kind of direct relationship. In practice, not all government departments or agencies would carry out consultation at the policy formulation and development stage for various reasons, as discussed earlier. Some of them prefer to wait until the drafting process begins. Too frequently, such an approach results in the involvement of drafters in the consultation process. Although the classical theory has been that drafters should not be involved in policy matters,104x H. Thring expresses the view that drafters must not consider policy or substance of law; they must only concentrate on the form of the law. See Stefanou, 2008, p. 321. In this respect, Stefanou suggests that in determining the extent of drafters’ involvement in policy matters the size of one jurisdiction, whether small or large, does matter. See Stefanou, 2008, p. 322. the fact that some involvement would enhance the understanding of legislative proposal or address any issues or loopholes in policy intended should not be denied. Collaboration between the instructing officers, drafters and parties consulted during the drafting process would be useful and fruitful if effectively conducted.

Although there is a view that consultation should not be confined to any particular drafting stage,105x See Miers & Page, 1990, at 42. I hold that it should be limited to the understanding, analysis and design stage only, and should not be done at later stages. This is because when a drafter has embarked on composing and developing a bill, it would be too late and difficult for the drafter to make changes since the basic structure and conceptual elements of the bill have been established. Consultation at this stage would unnecessarily disturb the smoothness of drafting legislation.

Having said the above, it can be summarized that consultation relates to the drafting process in two ways: through drafting instructions and through consultation during the drafting process itself.II. Consultation and Efficient Drafting Process

I have identified the elements that constitute efficient drafting process, which are as follows:

Wasted financial cost is minimized.

Wasted human resources or effort is minimized.

Wasted time is minimized.

The risk of failure is minimized.

Clear-sailing.

These five elements are used for the purpose of evaluating and assessing the influence and contribution of consultation on the efficiency of the drafting process. The following explains how consultation influences the efficiency of the drafting process.

1. Wasted Financial Cost Is Minimized

The drafting process costs money in the sense that it involves the use of stationery, utility, materials and equipment. A draft of the bill prepared by a drafter can be numerous due to amendments, refinement and finalization. A lot of material resources are used in the process of coming up with a final version of a draft bill, not to mention the case where drafting is done in two languages, such as in Malaysia. If correction has to be made, it has to be made on both versions. This would definitely contribute to the budget of the Drafting Division.

So if consultation is not carried out or omitted or bypassed, there is a possibility that a proposed bill might have issues that still need to be discussed with stakeholders even though the drafting process is already at the end of the drafting stage or completed. By right, this should not happen if consultation is done in the first place. Any amendment or change in policies owing to second thoughts of instructing officers after a lot of noises being made by stakeholders or interested parties would result in the draft of the bill prepared by a drafter being subjected to redesign and reconstruction. This turning back would cause unnecessary or extra financial cost when redrafting has to be done to accommodate the stakeholders. It is even worse if the proposed legislation has been finalized through several vetting and redrafting stages. All costs that have been incurred would be wasted and in vain.

In Malaysia, when a bill is withdrawn for policy refinement or for further consultation, the normal practice is that the instructing officers or departments prefer to have a brand new bill, rather than using the withdrawn bill, all the more so if a bulk of amendments has to be done. Without doubt, extra costs in preparing new drafts and blueprints would be incurred.

So, in effect, if consultation is carried out, it would help to minimize the drafting cost because the overall cost of the drafting process could be reduced. This explains what is meant by minimum cost.2. Wasted Human Resources or Effort Is Minimized

The shortage of drafters, coupled with more legislation to draft, is a common problem, especially where a jurisdiction has a small drafting unit. In some jurisdictions, including Malaysia, drafters are tasked to draft both primary and subsidiary legislation. Some drafters may be loaded with enormous workloads with close deadlines. Therefore, drafters should use their efforts, skills and energy wisely and guard against unnecessary waste. To waste efforts, skills and energy means to waste time in drafting as well.

If consultation is carried out before the actual writing begins, this would give a drafter a clear picture of the directions of the legislative proposals, thus making it easier for the drafter to plan his work so that the drafter can work on the draft efficiently and in a timely manner. If a drafter has devoted all his efforts, skills and energy to one particular bill, which is subsequently withdrawn or rejected by the legislature owing to failure to consult, this would certainly frustrate the drafter,whose efforts in drafting and producing the bill are in vain. The wasted efforts, skills and energy could be more useful if it were used in drafting other legislation.3. Wasted Time Is Minimized

In legislative drafting, time is of essence, and drafting consumes a lot of time. Unremarkably, a drafting job is done under pressure of time as there is always a deadline to be met. Time constraint is a serious enemy of drafters. It is therefore very important for drafters to utilize their time wisely so as to ensure that every minute in producing draft bills is not wasted. Hence, one way to ensure that drafting is done without any wast of time is to have all issues and problems settled beforehand. Accordingly, it would be easier for drafters to carry out their job timely.

As explained earlier, consultation relates to drafting instructions, and it is worthwhile to reaffirm what Thornton says: “good drafting instructions can reduce drafting time”.106x See Thornton, 1996, p. 129. As has been argued before, if consultation is done at an earlier stage, a drafter could concentrate on drafting so that he/she could finalize the bill on time and meet any deadline set. If the process of writing and composing a bill is interrupted owing to problems and disputes concerning any stakeholder or interested party, this would disrupt the drafting process, and consequently more time is needed for entertaining the stakeholder or the interested party’s concerns. There is also a possibility that the drafter may not be able to finalize the bill on time. Should consultation be done earlier, time to draft can be fully utilized to do the job on time, satisfactorily and efficiently.

It is worth mentioning that in Malaysia, it is the Attorney General’s Chambers and Drafting Division’s mission to complete the drafting of principal legislation within 40 working days after all legal and policy issues are resolved. Too often, when the countdown on days starts to begin, the drafting job is interrupted by changes in policies for various reasons, one of which is accommodating the stakeholders or interested parties. At the late stage of drafting, changing directions in policy are unpleasant and unwelcome.4. Risk of Failure Is Minimized

Drafters’ tasks are not easy; too often, a legislative proposal involves highly technical matters, or affects the interests of a section of society. Drafters do not draft for nothing. They are responsible for transforming policies into effective and enforceable laws. They have to make sure that every draft they produce is not at risk of being defective or deferred by the legislature. If their drafts are at risk of being deferred or rejected by the legislature, then again, all of their efforts, time and cost would be in vain. One way to avoid it is through consultation.

Consultation is very significant in determining the risk of failure in the drafting process. As Miers and Page put it:A failure to consult may make the passage of the legislation more difficult; more importantly, it may prejudice its successful implementation and thereby the attainment of the government’s objectives. The brute fact is that these groups possess the capacity to “limit, deflect and even frustrate government initiatives”.107x Miers & Page, 1990, p. 41.

5. Clear-Sailing

Consultation before or at an early stage of the drafting process would facilitate the drafting process and make it clear sailing . This is because all issues and problems with regard to the legislative proposal that affect the interests of the public or any particular group or party have been thrashed out and eradicated. This would undoubtedly make the drafter’s job easier when no interruptions, obstacles or problems crop up during the drafting process. The clearer the policy is at the beginning, the smoother the drafting process shall be.

To sum up, consultation does influence the policy behind a legislative proposal. Having all issues concerning stakeholders or interested parties sorted out and gaining their mutual understanding and agreement before the actual drafting starts would manifestly influence and contribute to the efficiency of the drafting process. -

F. Analyzing Questionnaire and Findings

The study is on the contribution of consultation to the efficiency of the drafting process in Malaysia. A total of 34 questions (although the total number of questions was 35, actually there was no question number 15 because of numbering error) was posed to the respondents. The respondents were drafters currently working in the Drafting Division of the Attorney General Chambers of Malaysia. Out of the 36 drafters, only 24 responded to the questionnaire. Hence, this study represents the views of two-thirds, or 67%, of Malaysian drafters. In terms of experience, they range widely from just a year to 22 long years with an average of 5.5 years.

The questions were divided into three parts, as follows: (A) particulars of drafters, (B) consultation practices in Malaysia, and (C) efficiency criteria in the drafting process. As for the answers for parts (B) and (C), the respondents were provided with two types of answers, one in the form of the Likert scale with 5-point options to choose from, namely strongly disagree, disagree, neither disagree nor agree, agree and strongly agree. The other type was a ‘yes or no’ answer. For the purpose of tabulation of results, answers for the Likert scale are represented by numbers 1 to 5 for ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ respectively. As for the ‘yes or no’ answers, they are represented by Y or N, respectively. Respondents are identified as R1 to R24 even though there are some who are willing to have their names made known.

Some of the questions are not answered and are left blank by the respondents. It is not known whether the respondents did it intentionally or otherwise. But there are respondents who forget to tick the Y box because they answer the following related question, which means the previous answer has to be a Y.

The aim of the study is to prove whether consultation could contribute to the efficiency of the drafting process. To prove this hypothesis, drafters are asked whether consultation affects the efficiency criteria of the drafting process. Drafters are the right persons to ask as they are directly involved in the drafting process. They have wide experiences and are certainly in the know of the influence of consultation on any previous legislation, which they have drafted before. Answers from drafters would indicate positive or negative impacts of consultation on the efficiency criteria. If the total effects are positive, it can be said that consultation does contribute to the efficiency of the drafting process.

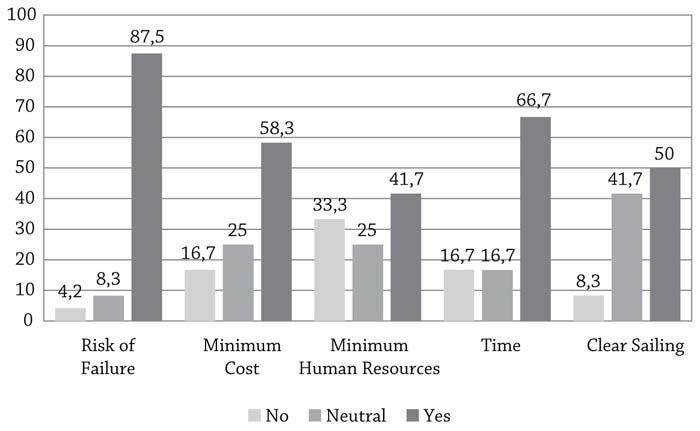

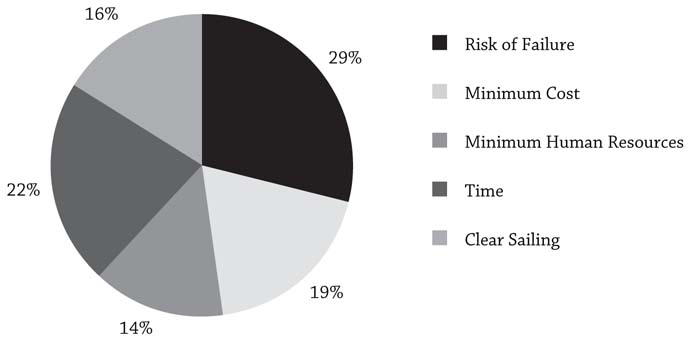

As mentioned in the earlier section, there are no definite efficiency criteria in the drafting process per se. Efficiency criteria used in this study are adopted from the public management and policy formulation studies. Five efficiency criteria have been ascertained, namely risk of failure, minimum cost, minimum human resources, time and clear sailing. To determine whether consultation facilitates an efficient drafting process, we have to calculate the scores for each criterion from the results of the survey. The point of ‘neither disagree nor agree’ becomes the cut-off point. Anything above it, that is, ‘agree or strongly agree’, will be considered as concurring with the suggestion.