-

A. Introduction: In the Name of the Father, the Sons and the Society

The institution of the head of state is a fundamental one that may be traced back to the leadership of the primitive hordes. It is fundamental because it is entangled with the creation of the society itself. We know from Locke, Hobbes and Rousseau that a society is an evolution, from the state of nature to the state of civilization. We may try here to slightly depart from the classical explanations given on the birth of society. Humans became civilized when they (finally) contained the empire of impulses and were able to live together. This is the starting point of the myth developed by Freud.1xS. Freud, Totem and Taboo, London, Ark 1983, pp. 1-17. The hordes of ‘sons’, the ‘brothers’, lived together under the ‘direction’ of ‘a father’. In order to develop, the brothers were forced to kill him. They then had to repress that need for murder, which became a taboo, a primitive rule that carved a micro-societal organization. The myth tells us about the desire and at the same time about the law.2xJ. Derrida, De la Grammatologie, Paris, Editions de Minuit 1967, p. 372. According to Freud the laws are prohibition of killing of the father and prohibition of incest. It is at the time of the feasts that incest becomes a crime too. Before there is no incest, as there is no prohibition of incest and no society. In the Freudian’s equivalent to the state of nature, the brothers had to kill the father. Then they moved towards civilization: their original pact was to refrain from killing the father. This original pact was considered by Rousseau as the act of birth of human society (l’acte de naissance de la société humaine). It became a sacred act, as Derrida reported: “To his eyes only one institution is sacred, one fundamental convention: it is, the social contract tells us, the social order itself, the law of the law, the convention that is the basis to all conventions...” (Il n’est sacré à ses yeux qu’une seule institution, une seule convention fondamentale: c’est, nous dit le Contrat social, l’ordre social lui-même, le droit du droit, la convention qui sert de fondement a toutes les conventions…).3xDerrida (1967), p. 373. The brothers had to commit the primal crime, the act of parricide. But they condemned it at the same time. The myth of the primal hordes and the killing of their father, the Father, not only demonstrates how intertwined the individuals and the group are, how civilization came, but also highlights the dimension of that Father for the civilization.

The Father is sovereign on his realm. He is the head of the horde. Further in history, the heads of the tribes became kings, and a monarchist system of government remained the one in place for thousands of years. The concept linked to the word sovereignty ‘remembers’ its genealogy and reminds us of the Father. It suggests the idea of supreme power and supreme authority in the same way the Father has the supreme power and supreme authority over the sons. It firstly relates to power that cannot be shared and in a second meaning, sovereignty refers to a monarch. It can also be attached to an institution (contained in the idea of sovereignty of Parliament, for example), or to some fictional entity (like that of the sovereignty of the nation or the sovereignty of the people, le public for Rousseau4xJ.-J. Rousseau, Du Contrat Social, Paris, Larousse 1973, p. 30.) in the course of the passage from monarchy to democracy.5xIn the association described by Rousseau, every individual associates to create a moral person. Rousseau identified that the republic (named city in the past), was called state (Etat) when ‘passive’ and sovereign (souverain) when ‘active’. Ibid., p. 30. He developed this idea explaining that “le pacte social donne au corps politique un pouvoir absolu sur [tous ses membres], et c’est ce même pouvoir qui, dirige par la volonté générale, porte, (…) le nom de souveraineté”. Ibid., p. 40. The question of the head of state is therefore central. It relates to the word sovereignty and has two parts. Primarily, why do we need, even nowadays, in a society that we assume to be a democratic one, someone like the head of state that ‘sits’ above us?6xIn the authoritative work of the Italian political scientist Sartori, three prototypes of system of government are defined: parliamentary (importance of parliament), presidential (importance of president) and semi-presidential (mixed). Each system has its model: the UK as the parliamentary model, the USA as the presidential model, and France as the semi-presidential model. I do not adopt here a strict legalistic view of any system of government, like Troper or Brunet that every system of government is in fact a parliamentary one with different organization. Then, in what sense that ‘figure’ is a symbolic one.7xIt is common knowledge that the president of the USA has power and powers that are more than symbolic. The different aspects of the word sovereignty may therefore conflict here. In the case of a head of state that is a monarch, we have a political and legal situation where he/she is the supreme ruler, the perpetual ‘head of state-sovereign’ that never dies.8xThe king never dies because of the creation of fictions: the perpetuity of the Dynasty, the corporate character of the Crown and the importance of the royal dignity. E.H. Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies, A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology, Princeton, PUP 1997, p. 316. But in the case of the role of sovereignty attached to an institution, such as the one of a parliament, or to a fictional entity, like the people or the nation, it may be more complex. Indeed, in these cases, the head of state does not disappear but remains present as another institution that is however not sovereign anymore. That said, the slippage from the ‘head sovereign’ to the ‘head non-sovereign’, does not eliminate completely the importance of the head. It even interferes with the institution or the fictional entity that is allegedly sovereign. As stressed by Laclau and Mouffle, “…democracy inaugurates the experience of a society … in which the people will be proclaimed sovereign, but in which its identity will never be definitely given, but will remain latent”.9xE. Laclau & C. Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics, London, Verso 2001, p.187. Perhaps, the core of the problem rests on the signifier sovereignty representing different signified concepts. The word sovereignty has one image accoustique that may be used in different types of political regime. What becomes therefore important is the signifier-word sovereignty over the signified concept.10xThe re-writing of Saussure (s/S) by Lacan (S/s) may be noted. Lacan considered that the signifier is placed over the signified. The signified becomes defined by the signifier, behind it. The same word used in different circumstances creates difficulties in our understanding of the institution of head of state on the chaotic road to democracy, mixing legal appreciation of the institution and the psychological aspect of the head, leader, father, Father.

In this paper I consider the symbolic position of the head of state and how this specific and particular ‘function’ still has its importance, how it has been defined, and how it operates. I start my enquiry by analysing the move from the sovereign-monarch to president-monarch. I then consider the question of authority and its link to ‘distance’ before looking in detail at the head of state and ‘the Father’ then to finish with the notion of the two bodies. -

B. From the Sovereign-monarch to President-monarch

I will use France as an illustration of what is at stake here. This section starts with an account of the French constitutional history touching the head of state and then an analysis of the case of Nicolas Sarkozy.

I. Tumultuous (Constitutional) History...

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, revolutions and changes in constitutions have established that the monarchy legitimated by its divine right, while abolished, was still present, through the institution of the head of state. This institution was absent from the 1793 First French Republic Constitution. The First Republic introduced a collegial conseil executive (Article 62). It was certainly a reaction to the previous constitutional architecture, the Constitutional Monarchy of 1791 (first post-revolution constitution) that kept the king as the head of state. The presence of the monarch in a Republican Constitution would always connect to the past regime. But this is not the sole explanation. The 1793 Constitution inaugurated a system based on the sovereignty of the people (Article 25), ‘something’ that was ‘one and indivisible’ and that could not be exercised by any portion of the people (Article 26). It also included the impossibility of one individual exercising it (Article 27): the person would be killed immediately by free men. This seemed to mirror the primal hordes and the parricide. It also fits rather well with the historical event that took place a few months earlier, when the king was removed and killed on the 21 January 1793. In that sense, the institution of the head of state was like a ghost in this first republican Constitution, but it became a very present reality in the 1848 Second Republic, a president receiving by delegation from the people-sovereign, the executive power (Article 43). Both periods finished with authoritarian systems of government. The 1793 Constitution was never enforced and the whole revolution period was ‘closed’ by the First Empire (Napoleon I). The 1848 Constitution ended with the Second Empire (Napoleon III). The experience of the French Third Republic may well be the best illustration of the word sovereignty ‘struggle’. Indeed, the ‘life’ of the Third Republic from the Marshal McMahon saga in the late nineteenth century, to its end, with the Marshal Petain is linked to its head. In 1871, Adolphe Thiers received the title ‘Head of the executive power of the Republic’ from the National Assembly empowered with the ‘sovereign authority’.11xRésolution de l’Assemblé Nationale ayant pour objet de nommer M. Thiers Chef du pouvoir exécutif de la République Française du 17 Février 1871, Bulletin des lois de la République Française, XIIe série, 2e semestre 1871. Partie principale, T. 2, n 48, Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1872, p. 71. Last accessed 22 November 2010. <http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k210059r/f79.image.pagination>. The institution’s title was modified a few months later and Thiers became president.12x‘Le Chef du pouvoir exécutif prendra le titre de Président de la République Française.’ Loi du 31 aout 1871, Bulletin des lois de la République Française, XIIe série, 2e semestre 1871. Partie principale, T. 3, n 62, Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1872, p. 113-114. Last accessed 22 November 2010. <http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k210060p/f130.image.pagination>.

This strange period of instability in French history corresponds with the end of the Second Empire and the Prussian invasion. In addition, the Republic was not established, even though it had been ‘declared’ on the 4 September 1870. The monarchists were very powerful and actually had the majority of the seats at the French parliament. In 1875 while the draft constitution was discussed and the reference to the Republic rejected by the monarchist majority, an amendment was introduced by deputy Wallon and adopted, stating “The President of the Republic shall be elected by the Senate and the Chamber”.13x<www.assemblee-nationale.fr/histoire/suffrage_universel/wallon/amendement-wallon-1.asp>. Last accessed 4 August 2008. The French Third Republic, the mythical Republic, was then created by a reference to its head of state. The presidents of the Third Republic very quickly became situated above the political arena, and therefore were heads of state in a position similar to a monarch in a constitutional monarchy. This situation prevailed throughout the Fourth Republic but the Fifth French Republic was established with the idea of a strong leader. Indeed, De Gaulle wanted a powerful head, responding, decades later, to Maurras’s comment that France always needed a head. Duverger echoed this point, citing Maurras in his famous monograph Echec au Roi: “the republic is a woman without a head”.14x‘La République est Une Femme sans Tête’, M. Duverger, Echec Au Roi, Paris: Albin Michel 1978, p. 21. It seemed that at the same time the decapitation of Louis XVI, was a real elimination of the head of state but everything has been done in the next two centuries to symbolically put the head back where it belongs, on top. The amendment of the Fifth Republic Constitution in 1962 consecrated the direct election of the head of state by the people. De Gaulle wanted to establish a mechanism of republican legitimacy equivalent to the divine legitimacy of the Monarchy.

One can analyse the ‘recruitment’ of the head of state in France under the Monarchy and the specific ritual electio, onctio, coronatio (election, ‘blessing’, coronation) and how it relates to the contemporary French president. The direct election introduced in the Fifth Republic Constitution in 1962 collapsed the three elements of the archaic ritual. In the modified design, the president was meant to lead the country by giving orders to his secretary, the Prime Minister, positioned ‘in front’. Although, there was no mistake that the head of state would lead the country, there would be always this fictional distance between the people and the head of state. The Prime Minister function was to act as a ‘shield’ or a ‘fuse’, and hence, as the person to blame or at least to take the blame ‘for’ the head of state. To sum up, the head of state of the Fifth French Republic became someone that had in his hands many instruments that created a certain distance between the people and him: this contributed to emphasize a symbolic position of the head of state. The French president is still a leader (close to the US president) but he also is the symbolic head, independent from parties, ‘formed’ by a specific ceremonial, living in ‘palaces’, ‘using’ the Prime Minister (who is more dependent from the political parties): the French head of state looks like a monarch. I would like to illustrate that point with the case of President Sarkozy.II. The Case of Nicolas Sarkozy

In the case of Nicolas Sarkozy, the presidency has appeared, at least according to the media reports, to be very controversial since the key 2007 elections. In fact, support of the president has declined sharply to make him the least popular president ever, with a level of popularity not even reaching 30% in October 2010.15x<www.lejdd.fr/Politique/Depeches/Sondage-Nicolas-Sarkozy-sous-les-30-JDD-228919/>. Last accessed 22 November 2010. However we witnessed some ups and downs of interest for this paper. For instance, from 2007 to January 2008, the support for the president dropped sharply from above 70% to around 35%.16x<http://sarkononmerci.fr/assets/cotemoy.jpg> and <http://sarkononmerci.fr/assets/lasarkocote.jpg>. Last accessed 22 November 2010. Despite this drop, it was clear his support was higher during the French presidency of the EU and during the state visit to the UK.

The candidate Sarkozy announced many reforms but no one knew that when elected, he would change the style of the governance of the state. This was corroborated by some opinion polls that suggested the people rejected the new president not for his reforms but because of his style. One of the numerous questions that could have been asked during this period was: what went wrong since the 2007 elections? To begin with, one may consider what has been referred to as the ‘hyper’ presence of the president on the TV: Sarkozy took the entire audio-visual scene for himself, to the extent that two French scholars, Jost and Muzet, coined the neologism téléprésident.17xF. Jost & D. Muzet, Le Téléprésident, Essai sur un Pouvoir Médiatique, Paris: L’aube 2008. Then, he became a president acting like a ‘business man’ and in that new way of operating, the president lost a certain prestige. Furthermore, the personal life of the president became first a public matter then a public liability. From January 2007 to October 2007, Nicolas Sarkozy and first lady Cecilia were ‘the presidential couple’. The first lady was even involved in the presidential work, like negotiating the release of Bulgarian nurses held hostage in Libya.18x<www.lexpress.fr/actualite/politique/infirmieres-bulgares-cecilia-sarkozy-s-explique_466370.html>. Last accessed 22 November 2010. The couple then separated. In October 2007, Nicolas and Cecilia Sarkozy were the first couple to divorce during a presidential tenure with a quasi-permanent press coverage.19x<www.msnbc.msn.com/id/21381415/ns/world_news-europe>. Last accessed 22 November 2010. This was followed by the president’s marriage to the top glamour model Carla Bruni.20x<www.liberation.fr/politiques/010123517-le-mariage-de-nicolas-sarkozy-et-carla-bruni-fait-courir-les-journalistes>. Last accessed 22 November 2010.

One may wonder whether Nicolas Sarkozy appeared more as a ‘president’ than a ‘the monarch’ as a consequence. But, it seems that in the process there has been a clear demonstration of the importance of the symbolic position of the head of state, that was illustrated by the lack of the ‘respect’ shown by the French people as a result of the new president’s behaviour. That said, and as a way of testing this point, one period should be carefully analysed: the one following the presidential wedding. During the period January to March 2008 an inversion in the support of President Sarkozy was witnessed.21x<www.orange.fr/bin/frame.cgi?u=http%3A//actu.orange.fr/sondage/006/BAROMETRE-POLITIQUE-BVA-ORANGE-L-EXPRESS.html>. According to this poll and to the newspaper Le Figaro, for the first time on the 15 January 2008, there was negative confidence in the president. <www.lefigaro.fr/politique/2008/01/15/01002-20080115ARTFIG00515-sondage-nicolas-sarkozy-dans-le-rouge.php>. Last accessed 4 August 2008. The state visit to the United Kingdom on the 26 and 27 March 2008 when Nicolas Sarkozy and his new wife were hosted by the British monarch appears as a key moment.22xThis is highlighted on page 11 of the poll LCI-Le Figaro dated 25 April 2008. <www.lefigaro.fr/assets/pdf/opinionway-2604.pdf> and on <www.lefigaro.fr/assets/flash/sondage1anSarko-3.swf>. Last accessed 22 November 2010. It seems that during the visit, the French people showed more ‘respect’, as demonstrated in the opinion polls. Nicolas Sarkozy became (finally) ‘the president’, their president, when he visited a monarch. What this tend to show, is the effect of distance in the creation of authority. -

C. The Question of Authority and Distance: A Non-written Practice, a Non-written Reform.

In this section, I deduct from the case of Nicolas Sarkozy, that distance, and its lack has an important incidence on the function of the head of state. That distance is mainly created by series of elements, an apparatus, and contributes to the authority of the function. I illustrate this again using the French case.

The way President Sarkozy operated was different to that of his predecessor/s and it did not seem to fit with the idea the French people have, somewhere in their imaginary, of their head of state. The directly elected head has become what he was supposed to be: a royal monarch. What is not written in the text of the Constitution is that the president is in a symbolic position and needs a specific dispositive,23xM. Foucault, ‘The Confession of the Flesh’, in G. Colin (Ed.), Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977, New York, Pantheon Books 1980, pp. 194-228. “The apparatus itself is the system of relations that can be established between (…) elements” that are “a thoroughly heterogeneous ensemble consisting of discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions–in short, the said as much as the unsaid.” apparatus, to appear as a president-monarch, like the judge needs to be in a specific ceremonial to be, become or be seen as the judge, as an embodiment of the law. Without distance, there is no demonstration of authority: therefore the head of state lacks of his magical side. There is a necessary distance that can be named the good distance. The case of Nicolas Sarkozy is of course a good illustration of this idea. The rejection of the president seems to be a consequence of his style that lacks distance. It gives a contemporary illustration of the relationship between monarchy and democracy that becomes a clear demonstration of how the monarchy is ‘present’ in the democracy, as a sort of ‘presence-absence’. As expressed by Winnicott “that is not a matter of saving the monarchy [but] the other way around: The continued existence of the monarchy is one of the indications we have that there exist here and now the conditions in which democracy (…) can characterize the political system”.24xD. Winnicott, ‘The Place of the Monarchy’, in Home Is Where We Start From, Essays by a Psychoanalyst, London, Penguin 1990, pp. 260-268, esp. p. 268.

To illustrate this point further, we may look at the date of May 2010 as one evidence of the changes. Prime Minister François Fillon was aiming for a record of longevity for a head of government. He was appointed in 2007 and after celebrating three years in office as Prime Minister, he was reappointed by the president. The Prime Minister does not appear to be ‘the fuse’ he used to be anymore. He is not ‘in front’. He is ‘only’ the close collaborator of the president that hides behind the president. In fact, Fillon became more popular than the president. The distance is non-existent anymore and it does not appear to help the function of the president. Because of its ‘strong’ head of state, the French Republic appears to be at the articulation between the monarchy and the democracy. According to the founders of the Fifth Republic in 1958, the French head of state used to lack monarchical apparatus. The head had to be ‘strong’ and as a consequence it was deemed necessary to give the function some royal aspects rather than borrowing obvious elements from the US presidential system of government. The head of state appears therefore as a return to the monarch, the return of the Father. -

D. Monarch, President: The Head of State and ‘the Father’

This section provides an analysis of the Father as ideal, and considers it with the two psychoanalytical notions of representation and identification. I then turn to the symbolic Father.

The president-monarch concentrates many elements of the king and in turn demonstrates a connection to the paternal figure. It is certainly an indication that one of the sixteenth century kings of France, Louis X11 received the title of Father of the people, Père du peuple.25xB. Quilliet, Louis XII, Père du Peuple, Paris, Fayard1986. This was such a important title and such a recognition of the true nature of this King, that even after 1789 he was considered worthy of becoming one of the Kings to be place in the Paris Pantheon, the burial place of the Revolutionary figures.26xL. Avezou, ‘Louis XII. Père du Peuple: Grandeur et Décadence d’un Mythe Politique, du XVIe au XIXe siècle’, Revue Historique, PUF 2003/1 - n 625, pp. 95-125, at p.116. There is, in the father, the idea of the sovereign, and in the sovereign the idea of the father. Besides, for Freud, the father is considered as an ideal: “In addition to its individual side, this ideal has a social side; it is also the common ideal of a family, a class or a nation.”27xS. Freud, ‘On Narcissism: An Introduction’, SE, 14 (1914), pp. 67-102, esp. p. 101. These words echo Rousseau’s idea of the family, the oldest and only natural society. Rousseau believed that the family was a model for every political society, in such a way that its chief was the image of the father, le chef est l’image du père.28xRousseau, Du Contrat Social, p. 20-21. ‘The chief is the image of the father.’ One cannot disregard the connection between these comments on the father, Father, and the image of the head of state and brings us to the notion of representation.

As stated by Freud, symbolism is the representation of one object by another.29xS. Freud, Moses and Monotheism: Three Essays, SE, 23 (1939), pp.1-138, esp. p. 98. The representation of something or someone by something else is also something magical. In the matter of heads of state, the merger between magical and real is extremely present. Although it is very difficult to understand for someone living in the twenty-first century, it is however something that was ‘normal’ in the past. For instance, King Solomon was considered to be both king and magician.30xP. Torijano, Solomon the Esoteric King: From King to Magus, Development of a Tradition, Boston, Brill 2002, p.193. More recently, Edward the Confessor was at the same time King and Saint, canonised in 1161, and Westminster Abbey was erected around his shrine which is still very much revered nowadays.31x<www.westminster-abbey.org/visit-us/highlights/edward-the-confessor>. Last accessed 22 November 2010. It is obvious that the divine legitimacy of the King lacks rationality. As explained by Laclau and Mouffe, a monarchy is “a society of a hierarchic and inegalitarian type, ruled by a theological-political logic in which the social order had found its foundation in divine will”.32xLaclau & Mouffe (2001), p. 155. We are confronted with a transcendental aspect of the polity: on the one hand, the vertical, hierarchic-non-egalitarian type, and on the other hand, the horizontal-egalitarian type. Obviously, it is easier to comprehend the first one than the other one because it better defines, through identification, the place of everyone.

Ultimately, “there is no institution without representation”.33xM. Wigley, The Architecture of Deconstruction: Derrida’s Haunt, The MIT Press, Massachusetts 1993, p. 51. An institution is something that is supposed to create a presence of a fiction (a legal person or something in the past) that is absent. Representation is the presence of the absent. In that sense, it gives ‘life’ to the institution: it institutionalizes. When Derrida commented on Rousseau’s thoughts about representation, he stated that the represented signified “the sovereign people” was represented by “the assembly”, therefore being the representative signifier.34xDerrida (1967), p. 418. The assembly became the institution that ruled for, on the behalf of the sovereign. The representation followed a primitive presence and brought a final presence.35xIbid. Therefore, the re-presentation occurred when the signified was absent. In addition, Derrida explained that the representative is not the represented (the signifier is not the signified) but is only the representative of the represented (only the signifier). Being the representative does not simply mean being the other of the represented. The wrong/bad of the representative or of the supplement of the presence, is neither the same nor the other. It arrives at the moment of the différance, when the sovereign will is delegated and, as a consequence, when the Law is written.36xIbid., p. 419.

The problem of representation is linked to the one of identification. The monarch, instance magical and authority, helps to identify. Identity and authority cannot be properly separated. It holds the society together, like the ‘parent’ caring for the ‘children’, knowing ‘what is good’ for the society. Identification to something ideal is described by Lacan in his vision of narcissus, during what he called the mirror stage, a process of ritual a young child undertakes when he wants to recognize himself in a mirror, with the approval of a third person, who provides a reference that frames the building up of the subject.37xJ. Lacan, ‘Le Stade du Mirroir Comme Formateur de la Fonction du Je’, Ecrit 1, Paris, Points, Seuil, 1999, p. 92-100. What is fundamental in the definition of the identity is constructed in the reflection, in the mirror, which also impacts on the symbolic: “the mirror stage is associated with the imaginary topology that exists prior to the symbolic register and yet is retrospectively constructed from it.”38xR. Feldstein, ‘The Mirror of Manufactured Cultural Relations’, in R. Feldstein, B. Fink & M. Jaanus, Reading Seminars I and II, Lacan’s Return to Freud, New York, SUNY Press 1996, p.136. It calls to something archaic. In the case of the head of state, the ceremonial is a very decisive tool that helps to recall the past. For instance, the costume of the head of state should be kept in mind like the costume of the monarch in regalia. Monarchs are also monarchs because they wear something that separates them from others. The British monarch is also a monarch because she wears something that differentiates her from the others, allowing her to be identified not solely as the eldest member of a British (or foreign) family,39xAct of Settlement 1700, s. 3: ‘not being a Native of this Kingdom of England’. See the comments made by Freud on the Jewish people disputing the foreign origin of Moses. Freud (1939), p. 68. but as Elizabeth II, encroached in the linage of the monarchy. The uniform operates as a demonstration of superiority of the social over the individual: the uniform of the monarch not only makes her ‘look like’ a monarch but also positions her as the authority. As a consequence, the uniform of the head of state makes him/her ‘look like’ a monarch and states authority. The symbolic role of the head of state is the emergence of authority in a democratic society, a society where equality between individuals is the most important element. But it is also a society where authority is decided by a third party, an incarnation of the Law as an ensemble of rules that allows individuals aggregated in a group to be civilized, to exist. Indeed, since the crucial moment of the social pact created by the alliance of the brothers, in the myth of the primal hordes, the presence of the Father that relates to the symbolic order is the key. The problem of distance contains the genealogy of what is important in the issue of the uniform of the head of state: the appearance. Our fascination with an ideal creates a mental image, an image ideal where is place the ‘I would love to be’, where the subject ‘I’ sees itself. It is where the subject would love the other to see it: I would love to be seen as this exuberant figure that is the monarch. When the monarch transforms in president, the head of state bears the responsibility of ‘keeping’ the monarch appearance. This is again a problem that relates to representation and identity in and of democracy. -

E. The Head of State and the Symbolic Father

I would like to go further and deeper in this section, by considering the notion of symbolic father, Father. The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan introduced the symbolic father, the third party, who acts as a reference. The idea of the tripartite relation child-mother-father was present in the legend of Oedipus developed by Freud in the Oedipus complex. The work of Lacan permits use of the triangular relation to analyse other phenomenon. It makes it possible to place the head of state in the position of the symbolic father, the authority and the law.40xIn the Lacanian theory’s schema L, Lacan uses the capital letter A the ‘grand autre’, translated in English as O, the big other. That is the position of the (symbolic) father, the Father, in the schematic transposition of the Oedipus complex. But it is also the metaphoric father and the capacity of representation. This central notion for Lacan has something to do with what is absent. It is both what lacks and the emptiness because something lacks.41xJ. Lacan, Séminaire 4, La Relation d’Objet, Paris, Seuil 1994, p. 36. This notion has to be considered together with the necessary presence of monarchy in the democracy developed by Winnnicott, the ‘presence-absence’. What seems crucial is that the lack cannot remain empty. It has to be filled, as there is a natural fear of emptiness, the horror vacui. This is the mission of the symbolic, which contributed to the beliefs of Lacan and Levi-Strauss to see “the social as constituted by relations of communication and symbolic exchange”.42xP. Dews, Logics of Disintegration, Post-Structuralist Thought and the Claims of Critical Theory, London, Verso 2007, p. 128. It is worth noting that this conception of the social phenomena as a system with certain coherence, as a structure, became the central thesis of Levi-Strauss’s structuralism: the symbolism and the social linked together to give the symbolic system43xM. Hénaff & M. Baker, Claude Lévi-Strauss and the Making of Structural Anthropology, University of Minnesota Press, 1998, p. 124. that Lacan will adapt in designing the symbolic order.44xDews (2007), p. 129. For Levi-Strauss:

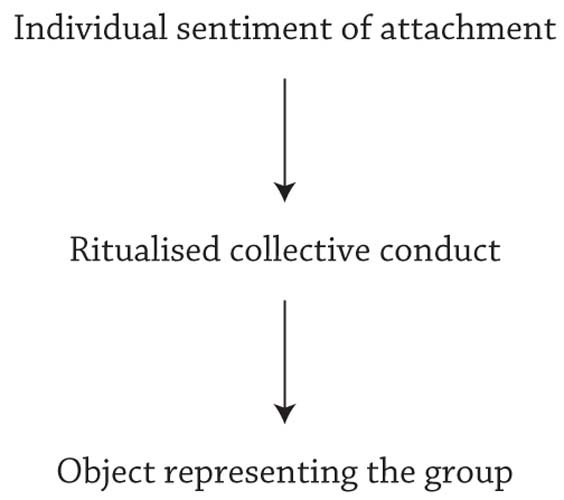

In order that social order shall be maintained … it is necessary to assure the permanence and solidarity of the clans which compose the society. This permanence and solidarity can be based only on individual sentiments, and these, in order to be expressed efficaciously, demand a collective expression which has to be fixed on concrete objects.

Figure 1

Figure 1It contributes to an explanation of the place assigned to symbols such as flags, kings, presidents, etc., in contemporary societies.45xC. Levi-Strauss, Totemism, London, Merlin 1964, p. 60.

This statement highlights the ideas of permanence and solidarity, which are also dear to Winnicott: stability is linked to the monarch. We may remember that when Spain, as a young democracy, was under attack in 1981, during the ‘23-F’, the coup d’état, the King was said to have saved democracy.46x<www.guardian.co.uk/world/1981/feb/23/spain.fromthearchive>. Last accessed 4 August 2008. Then again, this story illustrates that democracy is lacking of something, a ‘something’ that could be ‘someone’. Democracy is an empty shell that needs to be filled. In the case of 1981’s Spain, the members of the ’23-F’ wanted to fill up the empty shell with the army or with the return to an authoritarian regime: something that was present, became absent and needed to be present again, re-presented, incarnated. What was needed was to fill up this emptiness with something or someone else and the King came along to do so. His spectacular address on the TV had primarily to do with the symbolic order. In the same way, what De Gaulle did when he came into power, was to modify the institutions to push them towards a monarchy, as a mean to anchor the system in the symbolic that has been cruelly lacking since the nineteenth century. For Levi-Strauss too contemporary explanations have roots in archaic situations, like totemism47xLevi-Strauss (1964), p. 85.: the relationship human-other species and the identification of the social groups by means of symbolic objects.48xIbid. Human societies are not based on relations of objects but have an intersubjective dimension. They are defined as symbolic places, where “action humaine par excellence est fondée originellement sur l’existence du monde du symbole, à savoir sur les lois et les contrats”.49xJ. Lacan, Séminaire 1, Les Ecrits Techniques de Freud, Paris: Seuil 1975, p. 255. “Human action par excellence is originally based on the existence of the world of symbol, that is to say on laws and contracts.”

The problem of the head of state is at the very articulation between monarchy (absent and represented) and democracy. The French head of state used to lack monarchical apparatus, according to the founders of the Fifth Republic in 1958, and as a consequence it was deemed necessary to give him some royal aspects. On the other hand, it is clear that the British monarch is within a democracy and needs to be in a democratic environment. There is, in the Father, the idea of the sovereign, and in the sovereign the idea of the Father, something that relates at the same time, to love and to hate, and to the attraction and the repulsion towards the paternal figure and the authority. As stated by Freud, “an identification with the father” is when “one’s father is what one would like to be”.50xS. Freud, ‘Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego’, SE, 18 (1921), pp. 65-144, esp. p.106. The people, the masses, le public, also want something else through its identification with the father, to the figure of the monarch that hides behind the head of state: an escape, a fantasy, a magical kingdom, something from our childhood like Disney’s Sleeping Beauty castle. The father became the head of the group, of the primal hordes, the one who gave rules to the group: He is the law-maker. In the same way, in Freud’s essay Moses and Monotheism, Moses “leader of his people” became “the kingdom’s ruler”.51xFreud (1939), p. 27. Contemporary institutions are our creation. But some institutions create ‘us’. In a society that we assume to be a democratic one we found the need for an institution like the one of the head of state. The Great Man, Moses was a single man that evolves into someone that ‘created’ a people out of random individuals and families.52xIbid., p. 107. He became ‘great’ because of his effect on his people, not because of who he was. Moses was with “paternal characteristics”.53xIbid., p.109. He became the Father because “there [was] a powerful need for an authority”.54xIbid., pp.109-110, esp. p. 109. We go back into the magical, into the link between sovereignty, the father (and Father) and God, that is found as root of the monarchy legitimated by divine right. It can be said that we created our institution of head of state. But have we really? This is an institution that functions like something that comes out of our memory, like a need to have present among us the father-figure. It is something that creates the civilization (the father-the sons; the totem-the taboos). This magical aspect goes deeper than the conscious idea of its power. It relates to authority. Furthermore, the magical side of the monarch is something that has been linked with the idea of two bodies of the king a “mystic fiction … divulgated by English jurists of the Tudor period”.55xKantorowicz (1997), p. 3. It is the distinction between “the King’s sempiternity and the king’s temporariness, between his immaterial and immortal body politic and his material and mortal body natural”.56xIbid., p. 20. A monarch has two bodies, a natural body and a political body, the corporation sole and the person of the monarch.57xM. Loughlin, ‘The State, the Crown and the Law’, in M. Sunkin & S. Payne, The Nature of the Crown: A Legal and Political Analysis, Oxford, OUP 1999, p. 57. The presence of a monarch has to be illustrated/supported by the idea of two bodies, one natural, psychological identity, direct, the person of the monarch, and the other one political magical, indirect, defined through the ceremonial, the dressing code and the apparatus. -

F. The Issue of the Two Bodies

We all know that a monarch has two bodies, a natural body, psychological identity, direct, the person of the monarch, and a political body, the corporation sole, political and magical, indirect, defined through the ceremonial.58xIbid. The two bodies of the monarch travelled into time. We may apply this notion to our current head of states, like Nicholas Sarkozy, and even consider the connex issue of lack of distance.

I. Two Bodies of the Head of State, Identification and Stability

One may realize that the strong connection between monarchy and democracy enables to ‘root’ in the past to construct the future. Let us consider the key issues of identification and representation and their relation to the symbolic function of the head of state. The ceremonial, the apparatus, contributes to this function, through the symbolic. If we consider for instance the uniform of the head of state monarch and the head of state president, we can imagine that like a theatrical costume, the uniform at the same time protects and creates a symbolic dimension. In the democratic moment of the state opening of Parliament we simply have a time given to a monarch, the Queen, to give her speech in the House of Lords. This is a moment of language established in specific place, linking time and space, through a mise en scène, re-enacting archaic rites, and therefore steering the process of identification. The ceremony surrounding the monarchy takes all its meaning, as a theatrical representation of concepts dressed up by the symbolic in an Oedipal like dispositif. This moment allows the meeting of different elements that permits to determine the place of everybody and everything, the place of the monarchy ‘in’ the democracy. It is then that the ‘presence-absence’ becomes for a short period present and incarnated. The head of state (president) like the monarch has ‘two bodies’, his personal one and the one of his function.59xThis is not without resemblance to the idea that the King or the Queen has two bodies, a natural body and a politic body, the corporation sole and the person of the Monarch. Ibid. The definition of both is helped by the ‘uniform’ the head of state has to wear, a ‘legal costume’ similar to the costume an actor will wear in a play. The costume of the head of state likes the costume of the monarch in regalia becomes a crucial tool for democracy. It contributes to hold the society together, like the ‘parent’ caring for the ‘children’: he ‘makes’ the Father an ideal, a subject supposed to know what is good for the society. The democracy, this empty space of power, has to be ‘filled up’. It is here filled up by recalling the monarchy, in a sort of return to the primitive social organization. It is filled with our own values, with the image that has been integrated in our psyche.

One consequence of the two bodies during the monarchy was the permanence of the monarchy because the second body institutionalized the head of state. When the ‘physical’ person died, the second body remained. The monarchy where “the king is maintained … permanent”60xD. Winnicott, ‘Discussion of War Aims’, in Home Is Where We Start From, Essays by a Psychoanalyst, London, Penguin 1990, pp. 210-220, esp. p.217. is present in the democracy where “one man [is invested] with permanence for a limited period”.61xIbid., p. 217. As I mentioned, the central problem is the lack and the emptiness because something lacks.62xLacan (1994), p.36. This needs to be read with my idea on the necessary presence of monarchy in the democracy as developed by Winnnicott, the idea of the ‘presence-absence’. The lack has to be filled. This is the role of the symbolic function of the president, the one recalling the archaic figure of the monarch.

And we replace this figure, this symbolic one, by something else (institution). In our conquest for better civilization, the sovereign head of state, a monarch sovereign, became a parliament, the people or the nation, that needed, in return, a head to consolidate the society. The idea of sovereignty therefore permits the democracy but it also highlights the impossibility to completely separate monarchy and democracy. The importance of the symbolic role of the head of state is here stability: The monarchy where “the king is maintained … permanent”63xWinnicott (1990), pp. 210-220, esp. p. 217. is present in the democracy where “one man [is invested] with permanence for a limited period”.64xIbid., p.217.

The transcendental aspect of the political found in the verticality of the monarchy challenges the horizontality of the democracy. But in some ways it brings back to the ideas of Rousseau on the mixed government with power shared equally between the legislative (the assembly/ies) and the executive (the monarch) as what characterized the government of England (that I will extend, for my demonstration, to the UK).65xRousseau (1973), pp. 75-76. Let us consider for a moment the specific place of the equilibrium between monarchy and democracy that is the House of Lords. Further to its legislative function, the House of Lords represents the illusion of immortality and redemption. That last idea should be considered with the stability that brings the monarch in a democratic system of government, designed around movement, changes and dynamics. It delimits a present space where the confluences of past, present and future are interwoven. It also positions the head of state in a permanent place. The ceremonial surrounding the monarch at the moment of the opening of Parliament, the moment of repetition that is the annual speech of the Queen appears as crucial because of the particular articulation of space and time, because of the where and when it is delivered. According to Winnicott, the House of Lords’ function should go further than its current one. It should be the house “to which the rulers who are directly elected by the people should be responsible”, like the ‘parents’ of the ‘parents’.66xWinnicott (1990), p. 239-259, esp. p. 254. Winnicott therefore believed that democracy needs something else than solely what makes it democracy (the elected institutions). He also believed that in institutions could be found an ‘adult’ side (the monarchy) and the ‘child’ side (the democracy).II. The ‘Two’ Nicolas Sarkozys and the Lack of Distance.

Considering the two bodies in the case of the French president tends to help the demonstration of the lack of distance. Somehow, because of his constant movement, because of his specific dynamic, and because of his way of using the media, we have difficulties to really know when Nicolas Sarkozy is the president of the French Republic and when he is the man Nicolas Sarkozy. His constant use of communication creates an immediacy that abolishes ‘the long time’ (le temps long), the ‘liturgic time’ that connects to the monarchy.

The French Republic is now the regime of the ‘short time’ (le temps court). And one may even note an acceleration of time. The presidential mandate changed from seven years to five years (since 2000) imposing a shorter period between elections. It is like if one wanted to accelerate even more the perception of the speed of time. In addition, the president will have only two consecutive mandates (since 2008): he will need to be quicker, faster, to go ‘stronger’, in reforming and ‘modernizing’. The spirit of the Fifth Republic looks more and more ‘presidential’. It seems to prove that there has been an operation of legal transplant coming from across the Atlantic. But in my opinion it is also something calling out the past for two connected reasons. First, the unlucky end of the Second Republic Constitution established as a transplant of the US Constitution and the experience of the ‘prince president’.67xThe 1848 Constitution did not allow the elected president to do more than one mandate of four years without a ‘cooling period’. This did not satisfy Louis Napoleon Bonaparte who, after a coup, created the Second Empire. The nephew of Napoleon I, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, elected president of the Second Republic in 1848, could not resist seizing power in 1852 and setting up the Second Empire as Napoleon III. The second reason, and perhaps it relates to this very point, the monarchy is still very present.

The bottom line in fact is that the republican spirit today is more than ever like what Guy Debord declared in his Thesis 164: “The world already possesses the dream of a time whose consciousness it must now possess in order to actually live it.” The ‘immediacy’ scrambles the distinction between the ‘two bodies’ of the head of state. Sometimes we can identify with the man Sarkozy. We like the young tanned smiling active ‘business man’ going all around the world to sell the French Haute Couture, the “Gastronomic meal of the French”68x<www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/8132563/UNESCO-world-heritage-list-France-on-course-to-have-gastronomic-meal-enshrined-as-world-treasure.html>. Last accessed 14 December 2010. or EDF and AREVA nuclear power plants.69x<www.indianexpress.com/news/india-france-to-sign-couple-of-accords-during-sarkozy-visit/718759/>. Last accessed 14 December 2010. This is the man that leaves the presidential car on the Champs Elysee after being elected to shake hands with ‘his’ people gathered in the streets of Paris to see him. We like the friend Sarkozy, the man who knows the singers and marries a top model, the cheerful guy… Is he ‘really’ our president when he acts like this? Is he a ‘brother’ or a ‘father’? The ‘primitive’ belief of the people in their president is to consider him as a father rather than a brother. He should be the monarch president. But Nicolas Sarkozy vanishes behind other masks. He is not in position of reference, of authority and we can only identify to him for a brief moment, not permanently. Because of this apparent absence of stability, he ‘loses’ us very quickly. That said, sometimes we can identify with the president and there he incarnates the country, he projects an ideal for France, through a mythical nationalistic discourse that structures a public space, a specific scene. During the celebration of D-Day 2009 for example, he instigated a distance. He decided not to shake the public’s hands but to send his wife to do so instead. One may dissect the opinion polls of the period 7 June to 8 January 2008. Identification and reference to the ‘two bodies’ take all their meaning there. We loved the successful ‘business man’ becoming president but we got bored of him very quickly, even faster when the president’s domestic affairs were made public… Then from January to March 2008, the man Sarkozy was portrayed to be profoundly affected by his love life because there was no distance. The trouble for the president is this lack of distance as there is nothing recalling the archaic French monarch here. While the person Sarkozy may be unsettling, the head of state needs to show stability.

It is extremely important to remember that “democracy is defined by the insurmountable boundary that prevents the political subject from becoming consubstantial with power”.70xC. Breger, ‘The Leader’s Two Bodies, Slavoj Zizek’s Postmodern Political Theology’, Diacritics, 31, 1 (2001), pp. 73-90, esp. p. 78-79. This particularity “means that [in the language of psychoanalysis] the place of authority is ‘a purely symbolic construction’ that cannot be occupied by any ‘real’ political official”.71xIbid., p. 79. Zizek explained that in a democratic society, the monarch, and let us consider for our purpose the more general term of head of state instead, because of the confusion surrounding the word sovereignty, guarantees the non-closure of the social.72xIbid. We can learn from the medieval jurists in the matter of filling the emptiness. They designed fictions to help the “uninterrupted line of royal bodies natural, with the permanency of the body politic represented by the head together with the members, and with immortality of the office, that is of the head alone”.73xKantorowicz (1997), p. 316. While the medieval monarchy found a solution to the problem of interrex, the permanence of inter regnum in democratic society takes its source from the fact that the throne is empty. In the case of a political system like France, the institution of the head of state president is not permanent (although the Constitution organizes solutions for vacancies74xSee also the point of having a vice-president in the USA to tackle the possible ‘emptiness’ of the head.). In the case of Britain, the monarch, through its presence in the House of Lords, assures that the place of authority, the pure theoretical construction that cannot be occupied by a (‘real’) politician, is in fact filled by the ‘piece of the Real’ that is the monarch.75xBreger (2001), p. 79. We need to keep in mind Laclau’s words, that the logic of totalitarianism has the same source as democracy.76xLaclau & Mouffe (2001), p. 186. The symbolic position of the head of state has, therefore, a major function. And Laclau borrows from Lefort the idea of “democratic revolution”, “a new terrain which supposes a profound mutation at the symbolic level”.77xIbid. It seems then that the presence of monarchy in the democracy acts as an obstacle to totalitarianism. Furthermore, as stressed by Breger, not only does the ‘natural’, mortal body of the king function as a support and incarnation of the immortal ‘body politic’; but this ‘body natural’ – a king’s everyday qualities – is also ‘transubstantiated’ once he occupies the symbolic position of king. His person is no longer available for degradation: the more we envision the king as an ordinary person – the more we stress even his ‘pathological’ traits – the more he remains ‘king’.78xBreger (2001), p.81.

The visit of the French president to the UK in Spring 2008, where the ceremonial contributed to this timeless dispositif by highlighting his position of sovereignty, positioned him in the trinity, in the triangle that opened up to the archaic French monarch. The place of the British monarchy, and the time of the official visit of the French president became where and how Sarkozy became identified, as a symbolic figure, positioned as the symbolic father in the Oedipal dispositif as analysed by Lacan: “It is in the name of the father that we must acknowledge the support of the symbolic function which ... identifies the person’s face the law” (C’est dans le nom du père qu’il nous faut reconnaître le support de la fonction symbolique qui … identifie sa personne à la figure de la loi).79xJ. Lacan, ‘Fonction et Champ de la Parole et du Language’, in Ecrits 1, Paris, Points, Seuil, 1999, pp. 235-321, esp. p. 276. “It is in the name of the father that we need to recognise the support of the symbolic function that identifies his person to the face of the law.” As stressed by Lacan, the symbolic function of ‘naming’ positions the subject. What is crucial is the symbolic position here that creates the head of state authority and relates to the sacral, closely linked to its transcendental archaeology: religion (God, the Father) and tradition (the monarch sovereign) meeting in the vertical link God→ King. The symbolic father, in the symbolic order, positions: it is the place of foundation that is (fundamental) for human actions. -

G. Conclusion

To conclude, we should ‘simply’ consider that heads of states are nowadays generally elected. But it does not mean their ‘powers’ are more or less important than non-elected ones. In a way, one of the components that we found in the case of elected heads of state is considered by Badiou: the distrust.80xWe also see how elections in a democratic process may be pushed in a rapid movement towards new elections, and why President Sarkozy has had unlucky polls. For Freud “[t]he distrust … provides one of the unmistakable elements in kingly taboos”.81xFreud (1983), p. 49. There is ultimately a rather strange but profound connection between our contemporary heads of state and the archaic monarch. I used the example of Nicolas Sarkozy to highlight the necessary distance, the connection with the archaic monarch, with the Father. The president needs to have l’étoffe d’un président, the ceremonial uniform of the president, the one of a monarch82xSee <http://tf1.lci.fr/infos/france/politique/0,,4058265,00-sarkozy-au-plus-haut-depuis-six-mois-.html>. Last accessed: 27 August 2008., that he started wearing when he visited the British monarch. The powers of heads of state are not in question here, but rather beyond only politico-legal considerations, what is important is their symbolic role. That is not a mere statement but a lucid psychological ‘reading’ of contemporary Constitutions. As Jones told us, “just as princesses cannot be abolished from fairy-tales without starting a riot in a nursery; so it is impossible to abolish the idea of kingship in one form or another from the hearts of men”.83xE. Jones, ‘The Psychology of Constitutional Monarchy’, in E. Jones (Ed.), Essays in Applied Psychoanalysis, London, The Hogarth Press 1961, pp. 227-234, esp. p. 229.

-

1 S. Freud, Totem and Taboo, London, Ark 1983, pp. 1-17.

-

2 J. Derrida, De la Grammatologie, Paris, Editions de Minuit 1967, p. 372. According to Freud the laws are prohibition of killing of the father and prohibition of incest. It is at the time of the feasts that incest becomes a crime too. Before there is no incest, as there is no prohibition of incest and no society.

-

3 Derrida (1967), p. 373.

-

4 J.-J. Rousseau, Du Contrat Social, Paris, Larousse 1973, p. 30.

-

5 In the association described by Rousseau, every individual associates to create a moral person. Rousseau identified that the republic (named city in the past), was called state (Etat) when ‘passive’ and sovereign (souverain) when ‘active’. Ibid., p. 30. He developed this idea explaining that “le pacte social donne au corps politique un pouvoir absolu sur [tous ses membres], et c’est ce même pouvoir qui, dirige par la volonté générale, porte, (…) le nom de souveraineté”. Ibid., p. 40.

-

6 In the authoritative work of the Italian political scientist Sartori, three prototypes of system of government are defined: parliamentary (importance of parliament), presidential (importance of president) and semi-presidential (mixed). Each system has its model: the UK as the parliamentary model, the USA as the presidential model, and France as the semi-presidential model. I do not adopt here a strict legalistic view of any system of government, like Troper or Brunet that every system of government is in fact a parliamentary one with different organization.

-

7 It is common knowledge that the president of the USA has power and powers that are more than symbolic.

-

8 The king never dies because of the creation of fictions: the perpetuity of the Dynasty, the corporate character of the Crown and the importance of the royal dignity. E.H. Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies, A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology, Princeton, PUP 1997, p. 316.

-

9 E. Laclau & C. Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics, London, Verso 2001, p.187.

-

10 The re-writing of Saussure (s/S) by Lacan (S/s) may be noted. Lacan considered that the signifier is placed over the signified. The signified becomes defined by the signifier, behind it.

-

11 Résolution de l’Assemblé Nationale ayant pour objet de nommer M. Thiers Chef du pouvoir exécutif de la République Française du 17 Février 1871, Bulletin des lois de la République Française, XIIe série, 2e semestre 1871. Partie principale, T. 2, n 48, Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1872, p. 71. Last accessed 22 November 2010. <http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k210059r/f79.image.pagination>.

-

12 ‘Le Chef du pouvoir exécutif prendra le titre de Président de la République Française.’ Loi du 31 aout 1871, Bulletin des lois de la République Française, XIIe série, 2e semestre 1871. Partie principale, T. 3, n 62, Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1872, p. 113-114. Last accessed 22 November 2010. <http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k210060p/f130.image.pagination>.

-

13 <www.assemblee-nationale.fr/histoire/suffrage_universel/wallon/amendement-wallon-1.asp>. Last accessed 4 August 2008.

-

14 ‘La République est Une Femme sans Tête’, M. Duverger, Echec Au Roi, Paris: Albin Michel 1978, p. 21.

-

15 <www.lejdd.fr/Politique/Depeches/Sondage-Nicolas-Sarkozy-sous-les-30-JDD-228919/>. Last accessed 22 November 2010.

-

16 <http://sarkononmerci.fr/assets/cotemoy.jpg> and <http://sarkononmerci.fr/assets/lasarkocote.jpg>. Last accessed 22 November 2010.

-

17 F. Jost & D. Muzet, Le Téléprésident, Essai sur un Pouvoir Médiatique, Paris: L’aube 2008.

-

18 <www.lexpress.fr/actualite/politique/infirmieres-bulgares-cecilia-sarkozy-s-explique_466370.html>. Last accessed 22 November 2010.

-

19 <www.msnbc.msn.com/id/21381415/ns/world_news-europe>. Last accessed 22 November 2010.

-

20 <www.liberation.fr/politiques/010123517-le-mariage-de-nicolas-sarkozy-et-carla-bruni-fait-courir-les-journalistes>. Last accessed 22 November 2010.

-

21 <www.orange.fr/bin/frame.cgi?u=http%3A//actu.orange.fr/sondage/006/BAROMETRE-POLITIQUE-BVA-ORANGE-L-EXPRESS.html>. According to this poll and to the newspaper Le Figaro, for the first time on the 15 January 2008, there was negative confidence in the president. <www.lefigaro.fr/politique/2008/01/15/01002-20080115ARTFIG00515-sondage-nicolas-sarkozy-dans-le-rouge.php>. Last accessed 4 August 2008.

-

22 This is highlighted on page 11 of the poll LCI-Le Figaro dated 25 April 2008. <www.lefigaro.fr/assets/pdf/opinionway-2604.pdf> and on <www.lefigaro.fr/assets/flash/sondage1anSarko-3.swf>. Last accessed 22 November 2010.

-

23 M. Foucault, ‘The Confession of the Flesh’, in G. Colin (Ed.), Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977, New York, Pantheon Books 1980, pp. 194-228. “The apparatus itself is the system of relations that can be established between (…) elements” that are “a thoroughly heterogeneous ensemble consisting of discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions–in short, the said as much as the unsaid.”

-

24 D. Winnicott, ‘The Place of the Monarchy’, in Home Is Where We Start From, Essays by a Psychoanalyst, London, Penguin 1990, pp. 260-268, esp. p. 268.

-

25 B. Quilliet, Louis XII, Père du Peuple, Paris, Fayard1986.

-

26 L. Avezou, ‘Louis XII. Père du Peuple: Grandeur et Décadence d’un Mythe Politique, du XVIe au XIXe siècle’, Revue Historique, PUF 2003/1 - n 625, pp. 95-125, at p.116.

-

27 S. Freud, ‘On Narcissism: An Introduction’, SE, 14 (1914), pp. 67-102, esp. p. 101.

-

28 Rousseau, Du Contrat Social, p. 20-21. ‘The chief is the image of the father.’

-

29 S. Freud, Moses and Monotheism: Three Essays, SE, 23 (1939), pp.1-138, esp. p. 98.

-

30 P. Torijano, Solomon the Esoteric King: From King to Magus, Development of a Tradition, Boston, Brill 2002, p.193.

-

31 <www.westminster-abbey.org/visit-us/highlights/edward-the-confessor>. Last accessed 22 November 2010.

-

32 Laclau & Mouffe (2001), p. 155.

-

33 M. Wigley, The Architecture of Deconstruction: Derrida’s Haunt, The MIT Press, Massachusetts 1993, p. 51.

-

34 Derrida (1967), p. 418.

-

35 Ibid.

-

36 Ibid., p. 419.

-

37 J. Lacan, ‘Le Stade du Mirroir Comme Formateur de la Fonction du Je’, Ecrit 1, Paris, Points, Seuil, 1999, p. 92-100.

-

38 R. Feldstein, ‘The Mirror of Manufactured Cultural Relations’, in R. Feldstein, B. Fink & M. Jaanus, Reading Seminars I and II, Lacan’s Return to Freud, New York, SUNY Press 1996, p.136.

-

39 Act of Settlement 1700, s. 3: ‘not being a Native of this Kingdom of England’. See the comments made by Freud on the Jewish people disputing the foreign origin of Moses. Freud (1939), p. 68.

-

40 In the Lacanian theory’s schema L, Lacan uses the capital letter A the ‘grand autre’, translated in English as O, the big other. That is the position of the (symbolic) father, the Father, in the schematic transposition of the Oedipus complex.

-

41 J. Lacan, Séminaire 4, La Relation d’Objet, Paris, Seuil 1994, p. 36.

-

42 P. Dews, Logics of Disintegration, Post-Structuralist Thought and the Claims of Critical Theory, London, Verso 2007, p. 128.

-

43 M. Hénaff & M. Baker, Claude Lévi-Strauss and the Making of Structural Anthropology, University of Minnesota Press, 1998, p. 124.

-

44 Dews (2007), p. 129.

-

45 C. Levi-Strauss, Totemism, London, Merlin 1964, p. 60.

-

46 <www.guardian.co.uk/world/1981/feb/23/spain.fromthearchive>. Last accessed 4 August 2008.

-

47 Levi-Strauss (1964), p. 85.

-

48 Ibid.

-

49 J. Lacan, Séminaire 1, Les Ecrits Techniques de Freud, Paris: Seuil 1975, p. 255. “Human action par excellence is originally based on the existence of the world of symbol, that is to say on laws and contracts.”

-

50 S. Freud, ‘Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego’, SE, 18 (1921), pp. 65-144, esp. p.106.

-

51 Freud (1939), p. 27.

-

52 Ibid., p. 107.

-

53 Ibid., p.109.

-

54 Ibid., pp.109-110, esp. p. 109.

-

55 Kantorowicz (1997), p. 3.

-

56 Ibid., p. 20.

-

57 M. Loughlin, ‘The State, the Crown and the Law’, in M. Sunkin & S. Payne, The Nature of the Crown: A Legal and Political Analysis, Oxford, OUP 1999, p. 57.

-

58 Ibid.

-

59 This is not without resemblance to the idea that the King or the Queen has two bodies, a natural body and a politic body, the corporation sole and the person of the Monarch. Ibid.

-

60 D. Winnicott, ‘Discussion of War Aims’, in Home Is Where We Start From, Essays by a Psychoanalyst, London, Penguin 1990, pp. 210-220, esp. p.217.

-

61 Ibid., p. 217.

-

62 Lacan (1994), p.36.

-

63 Winnicott (1990), pp. 210-220, esp. p. 217.

-

64 Ibid., p.217.

-

65 Rousseau (1973), pp. 75-76.

-

66 Winnicott (1990), p. 239-259, esp. p. 254.

-

67 The 1848 Constitution did not allow the elected president to do more than one mandate of four years without a ‘cooling period’. This did not satisfy Louis Napoleon Bonaparte who, after a coup, created the Second Empire.

-

68 <www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/8132563/UNESCO-world-heritage-list-France-on-course-to-have-gastronomic-meal-enshrined-as-world-treasure.html>. Last accessed 14 December 2010.

-

69 <www.indianexpress.com/news/india-france-to-sign-couple-of-accords-during-sarkozy-visit/718759/>. Last accessed 14 December 2010.

-

70 C. Breger, ‘The Leader’s Two Bodies, Slavoj Zizek’s Postmodern Political Theology’, Diacritics, 31, 1 (2001), pp. 73-90, esp. p. 78-79.

-

71 Ibid., p. 79.

-

72 Ibid.

-

73 Kantorowicz (1997), p. 316.

-

74 See also the point of having a vice-president in the USA to tackle the possible ‘emptiness’ of the head.

-

75 Breger (2001), p. 79.

-

76 Laclau & Mouffe (2001), p. 186.

-

77 Ibid.

-

78 Breger (2001), p.81.

-

79 J. Lacan, ‘Fonction et Champ de la Parole et du Language’, in Ecrits 1, Paris, Points, Seuil, 1999, pp. 235-321, esp. p. 276. “It is in the name of the father that we need to recognise the support of the symbolic function that identifies his person to the face of the law.” As stressed by Lacan, the symbolic function of ‘naming’ positions the subject.

-

80 We also see how elections in a democratic process may be pushed in a rapid movement towards new elections, and why President Sarkozy has had unlucky polls.

-

81 Freud (1983), p. 49.

-

82 See <http://tf1.lci.fr/infos/france/politique/0,,4058265,00-sarkozy-au-plus-haut-depuis-six-mois-.html>. Last accessed: 27 August 2008.

-

83 E. Jones, ‘The Psychology of Constitutional Monarchy’, in E. Jones (Ed.), Essays in Applied Psychoanalysis, London, The Hogarth Press 1961, pp. 227-234, esp. p. 229.

European Journal of Law Reform |

|

| Article | The Importance of the Symbolic Role of the Head of State |

| Keywords | head of state, monarchy, democracy, symbolic, Sarkozy |

| Authors | David Marrani |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Abstract Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

David Marrani, 'The Importance of the Symbolic Role of the Head of State', (2011) European Journal of Law Reform 40-58

|

Why do we need, in a society that we assume to be democratic, someone that reminds us of the archaic organisation of humanity, someone like a head of state? We know that the ‘powerful’ heads have now been transformed, most of the time, in ‘powerless’ ones, with solely a symbolic role, often not recognised. So why do we need them and how important are they? Because they are part of our archaic memory, images of the father of the primitive hordes, and because they ‘sit’ above us, the symbolic role of the head of state can be read with the glasses of a psychoanalyst and the magnifier of a socio-legal scholar. This paper is a journey in time and space, looking at the move from the sovereign-monarch to the president-monarch, unfolding the question of authority and its link to ‘distance’ but also the connection to ‘the Father’ and the notion of the two bodies. |

Dit artikel wordt geciteerd in

- A. Introduction: In the Name of the Father, the Sons and the Society

- B. From the Sovereign-monarch to President-monarch

- C. The Question of Authority and Distance: A Non-written Practice, a Non-written Reform.

- D. Monarch, President: The Head of State and ‘the Father’

- E. The Head of State and the Symbolic Father

- F. The Issue of the Two Bodies

- G. Conclusion

- ↑ Back to top