-

A. What is ‘Good Governance’

I. Terms

Many important institutions, like the World Bank, OECD, the European Union (EU), etc., have made use of the context of “good governance” and developed very similar principles and criteria for improving structures, procedures, manpower of international cooperation, state- and substate-level administration. We take the definition used by the World Bank:1x <http://go.worldbank.org/MKOGR258V0>, 2009-10-25.

We define governance as the traditions and institutions by which authority in a country is exercised for the common good. This includes (1) the process by which those in authority are selected, monitored and replaced, (2) the capacity of the government to effectively manage its resources and implement sound policies and (3) the respect of citizens and the state for the institutions that govern economic and social interactions among them.

II. ‘Government’ and ‘Governance’

It should be mentioned that ‘governance’ is a much broader term than ‘government’, which concentrates on state actions – versus society and market – and analyses democracy, hierarchy, decision-making party- and interest groups competition, statutory regulation and delivery of social goods and services by administrative organization. ‘Governance’ looks at steering and self-regulation on both sides, public and private (corporate governance!), ‘Governance’ analyses state and market as a network (public/private partnership!), coordination, negotiations, adoption, compromise, co-production and network management.

The approach of governance is broader than government – methodologically as well. Government, parliament, administration and judiciary are mostly imprinted by constitutions and law, whereas governance has a multidisciplinary perspective: economy – effective and efficient delivery –, political science and sociology – how does the private sector work as compared to the governmental side? – and – of course – the law: the Human Rights-Rule of Law-Democracy as the frame of our states, responsive government, participation of citizens and other stakeholders etc. In other words: ‘governance’ looks at governing not only inside, but also outside the institutional core of superior authority of the state, brings the local level as well as autonomous universities, chambers of commerce, bar associations etc. into sight.III. Principles

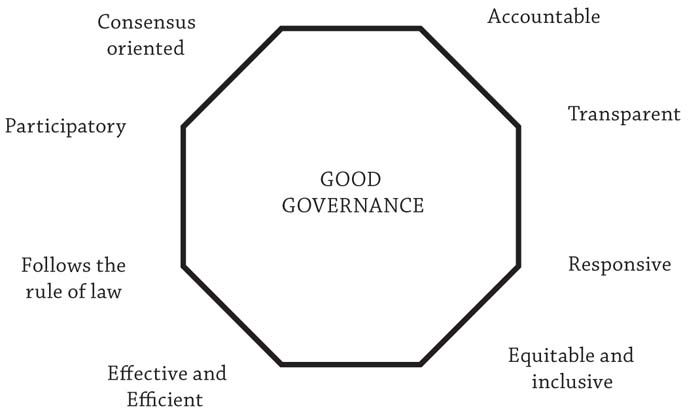

The main principles of good government are derived from a wide array of international and national sources and experiences. They enjoy broad acceptance across countries with differing social, cultural, economic and political systems and have been tested in comparisons and cooperation worldwide.2x The Rule of Law Index 2.0, South Africa Country Profile, Nov. 2009.

The key elements are:Government must be close to the people; the state serves the people, not the people the state.

Government must be legitimized (in a democracy by the people), effective, efficient, and accepted.

Government must have a positive effect on society, innovation, and the market. The state should set the framework, improve competition, innovation, growth, transparency, participation, and development in all sectors, public and private.

Transparency is based on the clarity, simplicity, and comprehensibility of government and society; transparency fosters trust in the reliability of state actions – they must be implemented.

Governance requires that state and private actions obey the law: separation of powers, monitoring, and guaranteed access to the judiciary for every citizen.

IV. Again: What is ‘Good Governance’? 3x <http://www.olev.de/g/good_gov.htm>.

-

B. Goals and Effects

I. Good Governance – a Multi-tasking Approach

The main goals of good governance are consented, however, not the tools for implementing and effectuating the goals. In Section IV this paper will identify some experienced tools.

It is important for any government, regardless of level, to strengthen its capacity to anticipate and manage risks and react to complex problems in a changing environment.4x OECD: Government at a Glance 2009, Paris, 2009, DOC 10.1787/978926407, 5061-en, pp. 22 et seq. Government has to identify clear policies and objectives within an overall vision of where the entity which it is in charge of is going. People need to better understand the political projects. Clear long-term objectives and priority setting are needed. In the areas of government, namely in the ‘machinery of government’, this requires:policy (stability and flexibility of political steps, well organized, according to the subsidiarity principle and comprehensive to the people);

regulation (less quantity, more quality of legislation and other regulation, consolidation);

administration (effective implementation of regulations and reliable and organized day-to-day administration, not starting from structure but with focus on people, because ‘the citizen is the boss’);

judiciary (subject to law – and only to law! – independent and accessible for everybody);

private sector (‘stakeholder participation’ in decision-making, partner in ‘sourcing out’ management – but not ‘in core fields of sovereign power’ of the state).

II. Good Governance – a Multi-level Approach

There are regulations, recommendations, suggestions, ‘white/blue/green’ papers of all sorts for ‘better governance’ on international, supranational (European) and national levels – and (not to forget!) valuable experiments, experiences and results. They focus on different aspects of good governance and consequently it is useful to take note of them, although:

They agree that governance, government, and administration are for the people and must be efficient, simple, speedy, must provide for integrity of the source and trust for the ‘consumers’.

On an international level OECD5x Fn. 4 p. 32. underlines the fact that good public services and citizens’ access to it is a vital precondition for economic development.

On a transnational – namely European – level the White Paper6x European Governance, White Paper, 25.07.2001, COM(2001) 428 final, pp. 7 et seq. makes the point that European standards of governance in a rule-of-law democracy require devolution of decision-making within the hierarchy as well as new instruments for reducing bureaucratic burdens, for example by decreasing the number of legal instruments (deregulation).

In addition it is the European Union that says that governments in such a network will eventually be judged by its ability to add to national policies and address people’s concerns more effectively on an EU- and international level.7x Fn. 6 p. 9. Thus national policy – like in Germany – comes into perspective.

Currently there are two aspects of good governance discussed and required on all levels: (1) transparency, anti-bribery, anti-corruption; and (2) efficiency and effectiveness of governance.

III. The International Level

Firstly, the United Nations Convention against Corruption8x Adopted by the General Assembly by Resolution 58/4 of 31 Oct. 2003, entered into force on 14 Dec. 2005 <daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N03/453/15/PDF/N0345315.pdf?OpenElement>. has to be mentioned as a tool which, in theory – not in practice! –, is accepted by every state. The World Bank links the principles of good governance to the ongoing efforts of the G8 and G20 for supporting propriety, integrity and transparency in business activities.9x Fn. 1, p. 3. The World Bank’s priorities for good governance are

voice and accountability;

political stability and the absence of violence;

government effectiveness;

regulatory quality;

rule of law; and

control of corruption.

The OECD as a producer of reliable data, useful for country comparisons, and of analyses and even practical ‘toolkits’ is probably the most relevant international source for help in improving good governance in a given country. The OECD is a unique forum where governments of 30 democracies work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalization. It helps states to respond to new developments and concerns. It is true that many – if not most – publications, declarations etc. of OECD touch at least on important features of good governance.10x Fn. 4, pp. 9 et seq. and pass.; OECD, Public Governance and Territorial Development, Directorate, Public Governance Committee, Report on the Consultation with the Stakeholders, Draft Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying, GOV/PGC (2009) 14, 24 Dec. 2009.

In fostering good governance OECD sets the following priorities:evidence based policy-making;

integrity in the public sector, credibility, and trust;

regulatory management, Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA), and simplification strategies;

coordination of policies and programmes across levels of government (multi-level government);

private sector, interaction between the public and private sector;

human resources management; and

fiscal sustainability, revenues, expenditures, and budget procedures and practices.

IV. The European Level/Supranational Level

Of course a supranational network of states like the EU – although not a federation, not even a confederation – has (under a constitutional treaty) legal instruments which bind member states and by application can integrate members or at least “bring them close together” and can set principles and guidelines for better governance in the member states which are otherwise socially and economically very divergent. The European Union is one example of emerging nucleuses of cooperation in a globalized world. The EU has delivered 50 years of stability, peace and economic prosperity.

By binding rules and various political decisions11x In more detail Fn. 6 pass. the EU Commission, council of ministers and parliament have focussed their good governance-policy on the following principles:

openness;

participation;

accountability;

effectiveness;

coherence;

proportionality and subsidiarity; and

flexibility.

It should be mentioned that some of these principles are explicitly part of the Treaty of Lisboa of 2009, namely proportionality and subsidiarity (Art. 5). Furthermore, the Copenhagen Criteria (of 1993, as strengthened in 1995) set standards which every state seeking membership in the EU must conform to and which in the accession procedures are rigorously applied:

political: stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities;

economic: existence of a functioning market economy and the capacity to cope with competitive pressure and market forces within the Union; and

acceptance of the Community Acquis (legal order): ability to take on the obligations of membership, including adherence to the aims of political, economic and monetary union.

Finally the President of the Commission, Mr. Barroso, on behalf of the Commission as the ‘Government of the Union’, on 20 Nov. 200912x European Parliament, Parliamentary questions, 20 November 2009, E-4949/2009. answered a parliamentary question in the field of good governance as follows:

The Commission has made significant progress in putting good governance principles into practice through several key actions:

through its Better Regulation Strategy by ……… (example: Impact Assessment);

a coherent set of “Minimum Standards for Consultation” […] (European Transparency Initiative (ETI);

the Lisbon Treaty also provides an opportunity to bring European citizens closer to the European institutions […] by introducing the European Citizens’ Initiative […]

Since the net of European Regulations and cooperation is knitted dense and denser, by comparison, unification and convergence of law a European Government and Administrative Space is evolving, which covers a lot of standards of good governance. Details will be shown in Section IV.

V. The National Level

By comparing national governance with other (and better?) examples, countries can reassess their roles, capabilities and vulnerabilities and improve their system step-by-step. Just as an example, one may look at the Better Government Programme of the Federal Republic of Germany13x Publication series “Moderner Staat – Moderne Verwaltung“, <www.staat-modern.de>. which has been running for more than ten years in the Ministry of the Interior and focuses on the following points:

vision: ‘the activating state’, which does not take all responsibilities himself but coordinates all levels of government and includes the private sector;

more orientation towards citizens;

decentralization and pluralism in a federal state; and

efficient government.

-

C. Constitutional and Legal Framework

I. Guidelines for Good Government

Creativity for developing models of effective governance in theory is unlimited, in reality and consequently practice, of course, possible only within the framework of a constitutional and legal order of a Constitutional State (which is a rule-of-law democracy) or, in other words – the Free Democratic Order, the elements of which are the legitimation of governance and government. The elements are Human Rights, Democracy and Rule of Law. Consequently the guidelines of reforming governance, as drawn from the constitution, are derived from a wide array of international sources that enjoy broad acceptance across countries of the Constitutional-State-Family, although with vastly different social, cultural, economic and political systems and certainly on different levels of development, however you choose to measure that.14x U. Karpen, Improving Democratic Development by Better Regulation, 2009 (in print).

In addition to these very broad guidelines of constitutionalism every reform-project, based in a state, is bound by nation-, state- or province constitution (in the case of European countries the acquis communautaire) and by quality standards of modern governance, including good legislation – and good administration standards. The details will not be mentioned here as they have already been partially mentioned above.II. Human Rights Standards

Governance Reforms have to obey the UN Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, in Europe the European Charter of Human Rights of 2000 and the National Constitution – Human Rights Section. For governance it is, in particular, the principle of human dignity and the body of individual freedoms and rights. Human dignity and freedom provisions are the background for the new understanding that it is the citizen who is at the centre of all administrative action. Administration is called upon to equip him/her with basic services and protect his/her rights. The principle of general equality is both a human right and an element of democracy. Protection of human rights in modern administration includes data protection and secrecy. Modern governance is orientated to protect the body of human rights by organization and procedure, be it by transparent and accessible organization or procedural instruments like participation, fair hearings, legal remedies, etc.

III. Democracy

This constitutional principle comprises – in the context of governance, namely public administration – three major aspects:

every administrative authority, be it at state, regional or local level, derives its power from the people’s will as it is laid down in law adopted by parliament and other democratically elected representative bodies;

the role of public administrative bodies towards citizens, entrepreneurs and wider society is imprinted by democratic elements. Democratic society calls for public administration which should be, on the one hand, perceived as the custodian of public interest and, on the other, as service-orientated activities directed towards citizens and society; and

the practical side and the most direct form of making democratic principles operational is participation of the citizens and their organizations in public affairs. Open, fully transparent and objective administrative procedures are one of the most important prerequisites for such participation.

Participation may take different forms, ranging from observation of public administrative actions – which is a form of control – via cooperation with administrative bodies through participation in the decision-making process. Governance should guarantee complete and effective protection of participatory rights of individuals in administrative proceedings; NGOs and other stakeholders should be admitted to participate in proceedings when a legitimate interest calls for such participation.

IV. Rule of Law

According to the World Justice Project15x Fn. 2, pp. 1 et seq. the following four categories are indicators of the quality standards of rule of law:

accountability;

good laws;

the guarantee that laws are enacted, administered, enforced, accepted, fair and efficient; and

access to justice for every citizen.

Rule of law is a constituent principle of the constitution. Since it is basic for a modern constitutional state, it is reflected in various facets of organization, procedures and requirements for governing, including – as a primary factor – personnel. Rule of law is applicable to the legislative power, government and administration – as the executive – and the judiciary:

parliament is bound by the constitution;

government and administration are bound by the constitution, law and basic principles of justice; and

the judiciary is bound by the constitution, law and basic principles of justice; the constitutional court is bound by the constitution.

The major elements of rule of law are explicitly mentioned in the constitution – like separation of powers –, others are interpreted from these principles by (constitutional) courts and jurisprudence. Among these are in particular:

due process of law/fair procedure, which are vested in human rights and are at the core of rule of law; no person is object, but rather subject of the governmental machinery; participation in all forms of procedure, if one’s interest is at stake;

guarantee not to be subjected to retroactive law;

access to legal remedies, to an independent judiciary and legal aid;

guarantee of trust of citizens in governmental authorities;

clearly defined responsibilities of authorities, transparent organization and fixed and objective procedures of all three powers; and

the right to damages, state liability.

All in all due process and fairness principles establish a “balance of weapons” between government and the citizen. If government and the private sector are coordinated or work together (for instance in ‘public/private partnership’), principles of due process are applicable for both sides.

Finally, the principle of proportionality is applicable not only for administration, but for any state action, with special importance, however, for administrative procedure. It is vested in human rights – government must interfere into rights and freedoms no more than is necessary to fulfil its tasks – and congruently in rule of law. Any governmental action requires the compliance with the proportionality principle, that means, administrative action may restrict an individual right only if the measure is suitable to attain the purpose prescribed by law: strictly necessary to obtain the purpose and adequate, i.e. the intervention does not imply a disadvantage that is out of proportion to the designed end.

-

D. Means of Governance

I. ‘Toolkit’ for Good Governance?

A lot of instruments for bringing forth, supporting and improving new forms of governance have been mentioned in passing by the foregoing topics and in some cases are not really new inventions. Namely, OECD and EU have developed and offer sort of ‘toolkits’ for better governance and better regulation. Here are – just thrown into a ‘basket’ – some of them. Among them are structural, functional, personal16x OECD, Fn. 4, p. 126. and other measures that are recommended to be implemented. Systems of civil servant’s legislation, administrative and fiscal decentralization, new regulation of administrative procedures, administrative simplification, one-stop-shops, and e-government are just some of them.

The main aim of these reforms is to raise the governance capacity of public government to such a level as to be able to effectively implement domestic legislation and, in Europe, also the acquis communautaire of the Union. A general reform path follows reorientation to citizens, entrepreneurs and the society as a whole. Service to citizens and citizen-orientation are the main goals of all current administrative reforms in the world.

Without exhausting what is available – according to the constitution of a given country, which wants to reform governance – some contents of the basket have been and will be mentioned. It goes without saying that a good constitution and good laws are an indispensable precondition for a modern, citizen-orientated administration. Law allows for regulatory management, better policies, regulations and delivery. Enforcement of public action is a key element for transparency and trust. Trust furthermore is based on legal remedies.17x OECD Fn. 4, p. 28. Flat hierarchies, including autonomous administrative elements (like chambers of medical doctors, pharmacists) add to flexible and participatory organization. The basic steps of legislative procedures are regulated in the constitution. Administrative procedures should be regulated comprehensively in a “Law on General Administrative Procedures”.18x Like the Support Group to Civil Service and Public Reform in Croatia (a project within the European Programme for accession of new members) has done in 2007/2008 in a 140-Article-Draft. The personnel must be guided by loyalty and integrity. It is vital to offer sufficient means and staff for delivering all public services: equipment, public procurement, namely of social offerings. The whole finance sector is to be prioritized: budget policy, revenues, and expenditures.

The whole area of participation has to be improved. This means, first of all, to call all levels of governance, including the private sector, into responsibility, to exhaust possibilities of cooperation and coordination, horizontally19x OECD, Fn. 4, p. 27. and vertically, namely with private stakeholders. Participation of all levels – obeying the principle of subsidiarity – brings in pluralism and creativity. Participation makes greater use of the skills and practical experiences of regional and local actors. It builds public confidence. The same is true if politics rely on expert advice. Of course, participation – namely of the public and private sector – carries the danger of conflict of interests which good governance must cope with.

Not all of these instruments, as being available in a ‘toolkit’, can be dealt with in detail. The following remarks, in a selective manner, will deal with the issues of organization, procedure and personnel. The whole field of finance – as important as it is – is a very special and complicated issue and will be postponed for another study. Finally, this paper will highlight four points, that are in the focus of good governance worldwide:transparency and conflict of interests;

effectiveness and efficiency;

standards of debureaucratization and better regulation; and

new challenges for governance.

II. Structures and Organization

The principles of good governance are to be applied on all levels of government, i.e. nation, province/state governments, local authorities, autonomous administrative bodies and agencies. The first task of good governance is to determine the proper level for delivering a public service, the ‘best level’ for regulation and administration. Of course, defence is a responsibility of the central administration; schooling should be regulated on a lower level. But the choice is not always that easy. Social activities are within the responsibility of all levels, taking into account the fact that in developed states 50% of expenditures are spent for social programmes.20x OECD, Fn. 4, p. 9.

The private sector must be considered from the beginning. Again, in developed countries 43% of values of public goods and services are delivered by the private sector.21x Fn. 20. The subsidiarity principle is a leading perspective for distribution of competences: governance should be service-oriented, close to the ‘consumer’, consequently bottom-top, not top-down. Coordination of all levels – vertically and horizontally – helps to fill the gaps:information gap;

capacity gap;

fiscal gap;

administrative gap: regional, functional, organizational; and

policy gap.

A coherent policy of the nation, state/province, local authorities – each in the area of its competence – is desperately needed.

The strategy of ‘New Public Management’ was developed some ten years ago and is still an effective tool for good governance. It is led by the principle of managerial autonomy. This principle is based on a bottom-to-top structure. Governmental entities on all levels enjoy a great deal of authority:they have their own budget;

are bound to ‘benchmarking’, comparisons with the ‘output’ and cost-effectiveness of other units;

develop their own ‘vision’, what they can do and where they want to go;

make arrangements about their goals and the budget they need – with higher supervisory units (the province/state, the nation etc.);

are subject to limited controlling, mainly that they stay within the framework of the law;

develop a ‘product-driven budget’ which means that they calculate how costly a given product would be (1 km of road building, 1 class in a new school, 1 unit of supply with water or electricity),of course they finally have to stay in the general frame of the budget, which has been appropriated to them; and

introduce e-government.

III. Procedures

Reform of administration as a core-element of good governance has to take into account the fundamental rationale that administrative procedures have direct effect on citizens’ day-to-day lives. Procedures indicate to the individual how the state treats its people. Procedures must be efficient, simple, and speedy. Citizens must have easy access to public service under due process and in a fair procedure. The individual is a partner, participant of governmental actions, not a recipient of ‘governmental grace’. So participation in good governance systems – of the ‘customer’ and other stakeholders – has to start at the very beginning of any procedure. A Participation Code of Conduct must set standards, focussing on what to consult on, with whom – including experts – and when. These could be partnership arrangements. Requirements of implementation of new procedure are inter alia:

permanent and professional monitoring of legal regulations and assessment of their appropriateness;

skilful, educated, qualified personnel; and

some quality control of implementation of administrative regulation: by appeals of the citizen, legal remedies, inspectors, ombudsmen, and other bodies.

The details of procedure, namely of administrative bodies, could – following other countries – best be regulated in a General Administrative Procedure Law. Such a law, basically, should serve four functions:

It provides an order of sequence of the decision-making process, coordinates the steps and allows for participation of the citizen.

It is an important tool for preserving procedural justice and protecting reliability of administrative Law; it adds to the acceptance of administrative decisions.

It is an essential step towards unification of administrative procedures in various fields of administration.

It enables administrative bodies to proceed and decide in an uncomplicated, appropriate and timely fashion.

Key elements of such an Administrative Procedure Law should be: preamble, general application for all administrative actions, legal definitions, namely of what an ‘administrative act’ is, uniformity of the system of administrative procedures; citizens’ access to public services and legal protection; enforcement and delivery, fair procedure, discretion, legal remedies, withdrawal and revocation of administrative acts, one-stop-shops, and e-government. There are many examples for good legislation of administrative procedure. But a basic requirement is – of course – a comprehensive survey of the existing legal situation in a country´s procedure.

IV. Personnel

As has been mentioned before, good governance on all levels is dependent on good personnel. One may talk of better structures and procedures and work on that. What counts in the end are the persons who do a good job in public service as well as in the private sector, who deliver public goods and services. Public employees must be independent, loyal to the state or other public unit and not to special interests, driven by ethical standards, and not corrupt. Building the right skills, attracting and retaining the right staff seems – in the light of experiences – to be the key factor of good governance. This observation starts with judging politicians and goes down to the lorry driver: everybody should be common-good and service-oriented, not party- or other interest-orientated. To use this tool requires a good human resources management which could be fostered and strengthened by effective public service legislation. Such legislation has been adopted – adequate to the culture and needs of a country – in many countries. There are excellent examples. Such a personnel-policy must – as a minimum – take into account the following goals:

education, training, permanent and professional updated education. A public employee must be self-confident, dare to decide – in his competence – on his/her own, should not be left in a position to prepare papers for the superiors’ signatures;

fair career chances and options, namely promotion according to performance;

sufficient salary to secure an independent position;

supervision;

protection against denunciation and whistle-blowing; and

rule-of-law shaped regulations for discipline.

This requires clear guidelines and rules of conduct for public officials on the one hand, but honest and transparent lobbying practices on the other.

V. Transparency and Integrity – The ‘Revolving Door’

As mentioned before, strong points for attaining good governance in current discussions are

transparency and integrity;

effectiveness and efficiency; and

debureaucratization and better regulation.

The percentage of countries which identify transparency as a core public service value doubled over the past decade to 90%.22x OECD, Fn. 4, p. 9. Transparency is undoubtedly an effective instrument to strengthen integrity and avoid conflicts of interest, corruption and abuse, and misconduct of public power.23x OECD, Managing Conflict of Interest in the Public Sector – A Toolkit, Paris, 2005 (ISBN 92-64-01822-0), p. 7. A lack of transparency and conflicts of interest are dangers to undermining public confidence in the integrity of public institutions.

There are two major transparency problems. Conflict of interest, on the one hand, is a major risk area in both the public and private sectors. The movement of employees between public and private sectors (the ‘Revolving Door Phenomenon’) has received particular attention in the context of the financial crisis.24x OECD, Fn. 4, p. 26. On the other hand, there are concerns over lobbying practices and demands for transparency in decision making, in order to avoid capture by interest groups.25x OECD, GOV/PGC (2009) 14, of 24 Dec. 2009 (a paper of the Public Governance Committee of OECD). Lobbying improves policy-making by providing valuable data and insight (in hearings etc.). However, a sound framework for transparency in lobbying is crucial to safeguard the public interest and promote a level playing field for businesses, particularly in the context of reform and economic crisis.

Traditional monitoring systems have proven unable to eliminate illegal activities. In various countries one tries to develop a ‘code of ethics’, be it written or unwritten, to prevent and resolve conflicts of that kind on both sides. On both sides, because retaining trust of the public in public institutions is an interest and responsibility of ministries, departments and agencies, local authorities concerned and their private partners. All sides – public, official and private contract partners – have to improve transparency:strengthen awareness of the principles of openness through stirring debates on both the governance challenges and the options available to foster transparency and integrity in lobbyism;

promote the understanding of principles and provide an avenue for key-stakeholders to express their views and involve them in the development of a national and international instrument;

ensure complementarities and synergies between principles and world-wide efforts of various actors to promote ‘good governance’ in lobbying;

build on a multi-disciplinary approach to enhance transparency and integrity in lobbying, including trade facilitations, corporate governance, anti-bribery, development and multi-level governance perspectives;

enable permanent cooperation with the stakeholders; and

regularly evaluate the relevance and acceptance of the rules of ethnic conduct, so defined, including citizens’ evaluation.26x UNESCO, <teachercodes.iiep.unesco.org/guidelines.html>; OECD, Fn. 25 et pass.

VI. Effectiveness and Efficiency – Public Action Must Work!

This is the second priority of good governance in the evaluation of OECD members.27x OECD, Fn. 4, p. 9. It scored 80%. Efficiency certainly is gaining importance in view of the desperate situation of public budgets everywhere. Effectiveness is a necessary prerequisite for efficiency, because a public act, which is not implemented and enforced, could never be cost-effective-relevant. Unfortunately, it is often the fact that laws in the books and laws in reality are divergent, that laws and public administrative actions as well as court decisions are of good wording, but not effective in practice.

VII. Better Regulation and Debureaucratization – Less Quantity, More Quality

Applying standards of better regulation is an important tool for gaining results of good governance. Proliferation of regulations, which nobody could overlook – neither administrative bodies, nor citizens, who are subject to them – could be channelled and reduced. Techniques of better regulation are developed, could be practically applied and – consequentially – taught for parliaments, legislators and others.28x Karpen, ‘Instructions for Law Drafting’, European Journal of Law Reform, Vol. 10, issue 2, 2008, pp. 163-181.

European Standards require better regulation in member states. The European Parliament applies them. Public trust is based on clarity, simplicity, comprehensibility, reliability of laws and other public actions. Some basic criteria are:regulation is only necessary if private, individual and civil group activities cannot cope with a problem;

one has to choose the proper level of regulation (subsidiarity);

the procedure must leave time for deliberation; procedures of legislation should not be hasty and hectic;

the formal quality of norms should be observed. General and abstract terms deserve preference over detailed regulation;

substantive quality needs careful deliberation: efficacy, effectiveness, efficiency, and stability of norms;

there must be a thorough cost-evaluation of law (Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA)); and

the law must be kept under control, amended if necessary, revised etc.

Better regulation, less regulative burdens on businesses and individuals, are – of course – an important instrument of debureaucratization. There are, however, new instruments for reducing bureaucratization. Administrative procedure reform must take notice of new techniques like ICT, e-government, one-stop-shops etc. It must be imprinted by the new perspective of citizen-administration-relations. Every administrative body acts in the service of the people, which is involved in the procedure by various forms of participation. The reform should include careful and appropriate regulation of the instance supervision. Territorial and functional decentralization has enabled local self-government units and legal entities with public competence to decide on an increasing number of administrative procedures. Since it touches the autonomous, self-government scope of activities, it is necessary to form instance supervision rather carefully in order to ensure the appropriate protection of citizens’ rights, as well as the local units’ right to self-government. De-concentration, decentralization and outsourcing public tasks to public-private-partnership are indispensable instruments of reducing bureaucratic burdens in modern administrative systems.

VIII. Questions and Challenges: A New Paradigm of Governance?

It seems that globalization and new and even larger responsibilities of the public hand on every level – especially in labour markets and social security fields – as well as a hitherto inexperienced acceleration of development, requires completely new forms of governance. Of course, these are new challenges, as – in fact – every historical period included for politics, governance, administration. This is not the place for speculation. Some points, however, which have been mentioned, may be underlined for future perspective of public responsibilities:

a better balance between government, market and citizens has to be found;

attracting and retaining the right staff and working on the right skills is rewarding;

there might be better forms of integrating policy-making and implementation;

effectiveness and efficiency of governance are the roots of better governance; and

fundamental public service values must be kept and strengthened under all circumstances: impartiality, legality, transparency, integrity, professionalism, and efficiency.

-

2 The Rule of Law Index 2.0, South Africa Country Profile, Nov. 2009.

-

4 OECD: Government at a Glance 2009, Paris, 2009, DOC 10.1787/978926407, 5061-en, pp. 22 et seq.

-

5 Fn. 4 p. 32.

-

6 European Governance, White Paper, 25.07.2001, COM(2001) 428 final, pp. 7 et seq.

-

7 Fn. 6 p. 9.

-

8 Adopted by the General Assembly by Resolution 58/4 of 31 Oct. 2003, entered into force on 14 Dec. 2005 <daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N03/453/15/PDF/N0345315.pdf?OpenElement>.

-

9 Fn. 1, p. 3.

-

10 Fn. 4, pp. 9 et seq. and pass.; OECD, Public Governance and Territorial Development, Directorate, Public Governance Committee, Report on the Consultation with the Stakeholders, Draft Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying, GOV/PGC (2009) 14, 24 Dec. 2009.

-

11 In more detail Fn. 6 pass.

-

12 European Parliament, Parliamentary questions, 20 November 2009, E-4949/2009.

-

13 Publication series “Moderner Staat – Moderne Verwaltung“, <www.staat-modern.de>.

-

14 U. Karpen, Improving Democratic Development by Better Regulation, 2009 (in print).

-

15 Fn. 2, pp. 1 et seq.

-

16 OECD, Fn. 4, p. 126.

-

17 OECD Fn. 4, p. 28.

-

18 Like the Support Group to Civil Service and Public Reform in Croatia (a project within the European Programme for accession of new members) has done in 2007/2008 in a 140-Article-Draft.

-

19 OECD, Fn. 4, p. 27.

-

20 OECD, Fn. 4, p. 9.

-

21 Fn. 20.

-

22 OECD, Fn. 4, p. 9.

-

23 OECD, Managing Conflict of Interest in the Public Sector – A Toolkit, Paris, 2005 (ISBN 92-64-01822-0), p. 7.

-

24 OECD, Fn. 4, p. 26.

-

25 OECD, GOV/PGC (2009) 14, of 24 Dec. 2009 (a paper of the Public Governance Committee of OECD).

-

26 UNESCO, <teachercodes.iiep.unesco.org/guidelines.html>; OECD, Fn. 25 et pass.

-

27 OECD, Fn. 4, p. 9.

-

28 Karpen, ‘Instructions for Law Drafting’, European Journal of Law Reform, Vol. 10, issue 2, 2008, pp. 163-181.

European Journal of Law Reform |

|

| Article | Good Governance |

| Keywords | international cooperation, state administration, substate-level administration, steering non-governmental bodies, principles of Human-Rights-and-Rule-of-Law, democracy structures, procedures and manpower of administration |

| Authors | Prof. Dr. Ulrich Karpen |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Abstract Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

Prof. Dr. Ulrich Karpen, 'Good Governance', (2010) European Journal of Law Reform 16-31

|

“Good Governance” is a term used worldwide to measure, analyse and compare, mainly quantitatively and qualitatively, but not exclusively, public governments, for the purpose of qualifying them for international developmental aid, for improving government and administration domestically, etc. |