-

1 Introduction

Pilots undertake high-risk work and so need to be able to understand the perspectives of all professionals they collaborate with, in the air and on the ground, in order to facilitate solid judgment and sound sense-making as the basis for their actions. This can lead to disagreements and conflict, which is not necessarily bad if it enables what is known as the sweet spot of conflict to be reached. This spot is the optimal point at which all perspectives come to the table, are exchanged and lead to new insights. Managing such a complex process is a highly commendable skill, and if pilots, most often the captain, can manage to keep the process focused on the content and not make it personal, the sweet spot can be attained.

This article elucidates the mindset and skills of pilots actively engaged in reaching for the sweet spot of conflict. It showcases the use of mediation skills in the cockpit and may even inspire business mediators to reflect on their own skill set. It may also provide new insights into the cultivation of desired skills and culture in the corporations they are working with. The article is inspired by the author’s PhD study of how KLM pilots manage conflict. In the interest of brevity, however, this article includes only a passing reference to this aspect of her work, and those interested in exploring this theme further are referred to her original work, cited in the footnote.

The word ‘pilot’ has been used in this work to mean the KLM pilots in the author’s study. The word ‘he’ refers to any member of the labour force. -

2 How Pilots Create a Positive Work Climate

To do a good job, pilots need a positive work climate that is open and constructive and favours the expression of all opinions. As each pilot, crew member and professional on the ground is fallible and makes mistakes, all professionals’ input is needed. The captain initiates this open climate, but all crew members have a responsibility to contribute to it. But what is an open, positive work climate?

2.1 Positive and Negative Work Climate

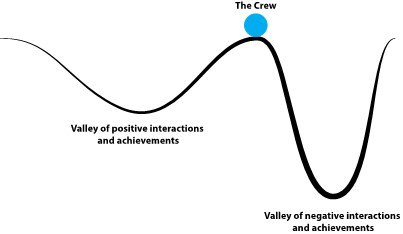

Social systems like crews can operate in a positive or negative climate, which can be visualised as two valleys (Figure 1):

Two Valleys or Work Climates for Crews.

In the positive valley, the interactions between crew members are constructive, resulting in high achievements. Communication is nuanced and refined, as is appropriate for the complexity of the work they execute together. They are interested in each other’s views, try to understand the logic and arguments behind them, and try to build a common perspective as a basis for action. In this exchange there is no power difference: all opinions are treated as equally important, independent of the rank or experience of the persons involved. This nuanced and complex exchange process makes optimal use of the intelligence, knowledge and insights available in the crew, and this explains the high quality of the decisions, actions and other achievements.

In the negative valley, emotions and power dominate the exchange of perspectives, which is driven by the conviction ‘I am ok but you are to blame’. In this climate, crew members are focused on the rightness of their views, which they want to impose on others. Their interaction is based on a power struggle as they try to prove that their vision and values are of a higher order and should be preferred. This lack of openness impedes the use of all the knowledge and insights present in the crew, and, unsurprisingly, this leads to negative results.

Research shows that it is five times more difficult to return from the negative valley to the positive valley than the other way around. The reason is that, compared with positive emotions, negative emotions have a five times stronger impact on relations. However, we need the positive valley to operate reliably and better make sure we create it and stay there. The positive and negative valley or climate are both present in crews, and it is their behaviour that determines which climate comes to the foreground and which recedes to the background. Most behaviour is culture based, and culture can be defined as norms for perceiving, thinking, feeling and acting. In KLM crews, the author’s study showed that the following cultural norms were responsible for bringing the positive valley to the fore.2.2 A Collective Mind

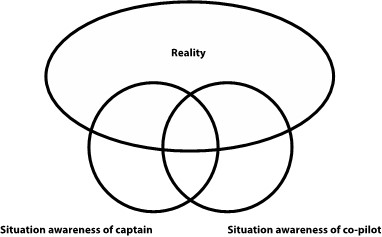

Pilots realise that they have limited perception and see only part of reality, as illustrated in the next drawing (Figure 2):

Differences in Situation Awareness in the Cockpits.

Pilots learn that they are aware of only a part of reality and not of the complete outside world. Their ‘situation awareness’ or knowledge of what is happening in the outside world is limited. There is overlap in their perceptions, but there are also differences. By exchanging and combining their views, they create a collective mind that is broader and understands more of what is going on. The more they perceive together, the better their operations are. As the illustration shows, they also perceive things outside reality, which is the area of fantasy. A common fantasy about what is going on can be dangerous as it is an unjust basis for actions. They try to identify their blind spots and fantasies by predicting what is going to happen. If their forecast is incorrect, something in their situation awareness is wrong and needs to be identified.

Creating a collective mind is not confined to the cockpit. Other crew members, ground personnel, air traffic controllers and passengers are all considered to have another situation awareness. The cockpit crew will consciously solicit those other perspectives to make their collective mind as performant as possible.2.3 Window of Safety

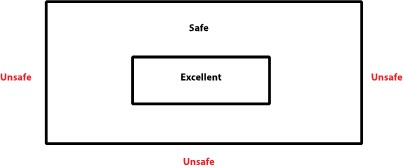

When captains consciously invite all crew members to contribute their perspectives, they will encounter a lot of different visions on the same subject. They will probably not appreciate all of them and wonder what to do. For this purpose, pilots develop their window of safety, and what they mean by this is illustrated in Figure 3.

Window of Safety.

A window of safety defines the boundary of their professional standards and delineates which visions and actions are considered good enough and which are not. Only when someone proposes something unsafe, a discussion is started. This boundary permits them to keep speed and velocity in their cooperation. They realise that the distinction between safe enough and excellent, which are both good, can be very personal and does not need to be addressed.

Pilots work with a window of safety not only to keep speed in their work together but also with another motive for adjusting to the preferences of their colleagues as long as these are good: they want to keep each other ‘happy’.2.4 The Zone of Positive Emotions

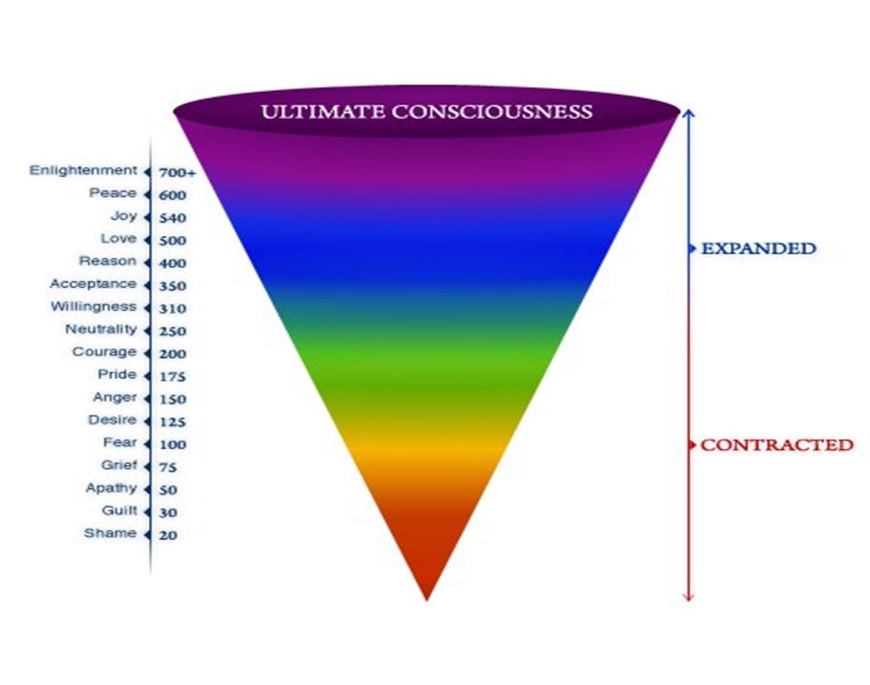

How pilots feel influences their perception and thinking process. Whenever they experience fear or anger, they become self-centred and register less of what is going on in the outer world. They do not want to get into this ‘tunnel vision’, which restricts their perception, as this type of functioning, according to research, is related to accidents. They want to have a broad horizon and perceive as much as possible. Negative emotions delimit their observation and positive emotions do the opposite, as is illustrated in the next drawing (Figure 4):

Emotional Zones and Consciousness.

Harmony, joy, reason, acceptance and willingness are examples of positive emotions that expand consciousness. This expansion surpasses neutral emotions. Negative emotions like anger, fear, grief, guilt or shame contract our consciousness, making them undesirable in the case of risky work in the cockpit.

A positive emotional climate can be created by small appreciative actions like showing interest, paying a compliment, asking for an opinion, seeking feedback, thanking for feedback, listening, doing something with what someone says, showing what one has learnt from the other, etc. These small gestures have an impact on how crew members feel towards each other. The higher the rank of the person making those gestures, the greater the impact. The study showed that captains know this and make use of the butterfly effect.2.5 The Butterfly Effect

The butterfly effect refers to the sensitive dependence on initial conditions and means that small causes can have large effects. Captains can make use of this phenomenon by acting immediately in the desired fashion when the crew meets at the beginning of a flight together. Crews at KLM work together for several days, whether they operate in Europe or intercontinental. Acting as a role model the moment the crew meets turns out to be more effective than doing so later on. Effective captains operate immediately accordingly to the desired climate and model the way the crew should perceive, think, feel and act. But captains are not solely responsible for the work climate; according to their job description, all crew members are responsible for creating a constructive work climate.

To create a positive work climate, the following four important activities have been described: creating a collective mind, working with a window of safety, staying in the zone of positive emotions and using the butterfly effect. Are all of these necessary, and is there no shortcut available to create a positive work climate? I am afraid there is not. It is the interaction of these different but related approaches that results in a constructive climate. -

3 Reaching for the Sweet Spot of Conflict

A disagreement or conflict is not necessarily a bad thing when we can reach for the sweet spot of conflict. How pilots strive for this optimum, which is the basis for a high level of work performance, will be elaborated next, as well as what they do when they do not succeed.

3.1 Conflict Definition

We all implicitly know what conflict is, but what do we mean by it? I distinguish here between beginning and escalated conflict. Beginning conflict is defined as a disagreement that has been brought up. One of the parties involved has made clear that something is happening that this person does not like or does not agree with. This announcement implies that the other person will probably react. Beginning conflict is hidden when no announcement to the other person is made. Beginning conflict can lead to tension within one of the individuals, which is not necessarily noticed by the other individual .

Escalated conflict, on the other hand, is unequivocally present owing to verbal and emotional outbursts. All parties involved perceive these voice elevations and emotional outbursts. Escalation can also have a social component when more and more parties get involved owing to the clearly visible presence of the conflict. Most people associate conflict with escalated conflict. In this paragraph we focus on beginning conflict, which is a moment of great potential as the disagreement can lead to different outcomes and the ‘sweet spot of conflict’ still remains within reach.3.2 The Sweet Spot of Conflict for Optimal Performance

The sweet spot of conflict is an optimal point or moment in which all perspectives come to the table and are exchanged and studied in such a way that the best insights emerge owing to deep and sound interpretations. In work situations, this is the basis for high performance. The ‘sweet spot’ is a term from sports like tennis, cricket or golf and refers to a place where a combination of factors results in a maximum response for a given amount of effort. A hit or swing will be powerful when it strikes the racket, bat or club on the latter’s sweet spot. The sweet spot of conflict can be considered as a way to bring up and treat different viewpoints with optimal effects and with minimal undesired effects.

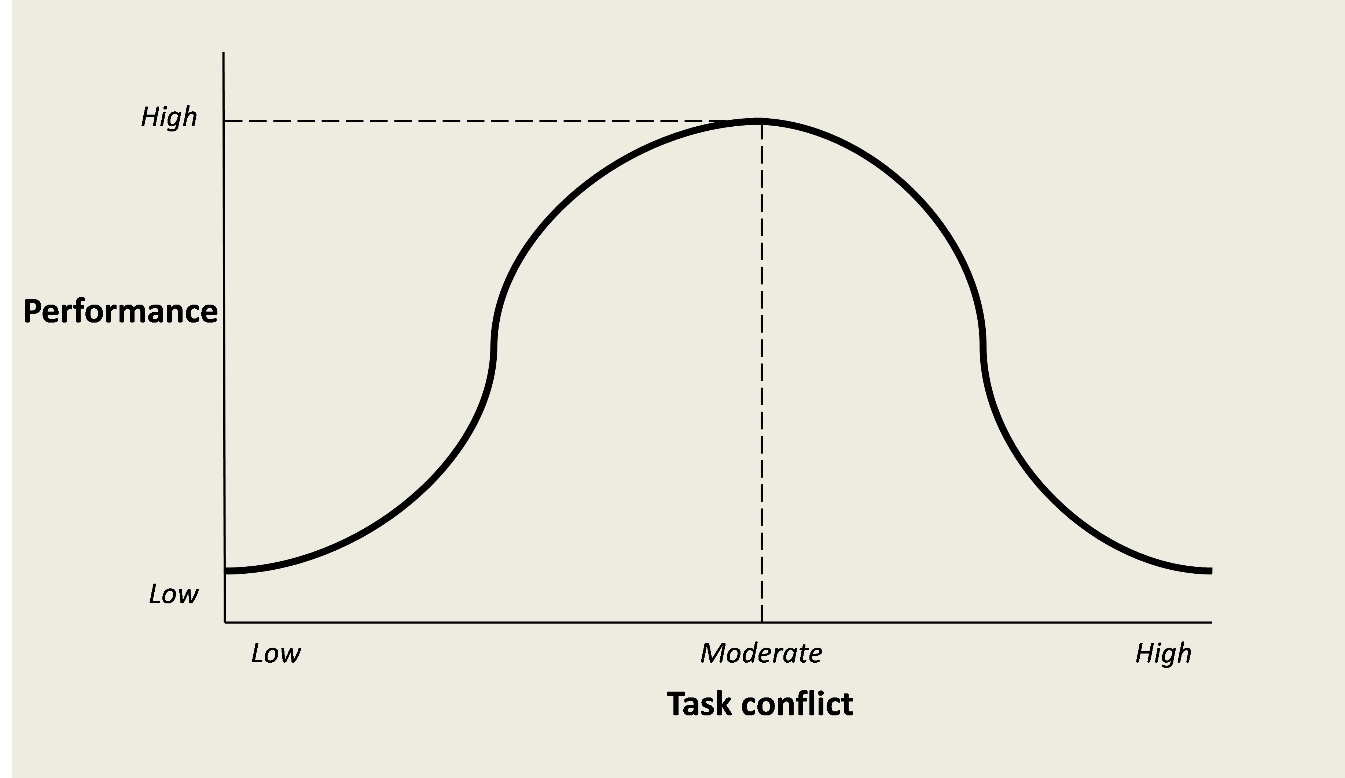

The sweet spot of conflict can be visualised as in the following drawing (Figure 5):The Sweet Spot of Conflict (inspired by Rahim, 2017).Rahim M.A. (2017). Managing Conflict in Organizations. Routledge.

This graph explains that moderate task conflict leads to optimal performance. Task conflict is conflict about the content of work. Whenever pilots disagree, two aspects are usually intermingled: the work itself and the person or persons involved. If they keep the issue focused on the content and do not make it personal, the sweet spot of conflict is within reach. If they make it personal by, for example, not taking the viewpoint of the other crew member seriously and attaching more importance to their own perspective, there is little chance they will reach this optimal point. To reach the sweet spot the issue has to be content oriented and be addressed as soon as possible before it develops further. If they wait too long, they might get too irritated to choose their words carefully and become personal.

At the left side of the graph, issues stay under the table as crew members involved do not bring them up for whatever reason. On the right side, escalation occurs, and the discussion of the issue leads to verbal and emotional explosions. Pilots learn to find their words so that they address disagreements and dislikes at the right moment. How do they do this?3.3 Three Different Conflict Processes in Crews: Converging, Freezing and Escalating

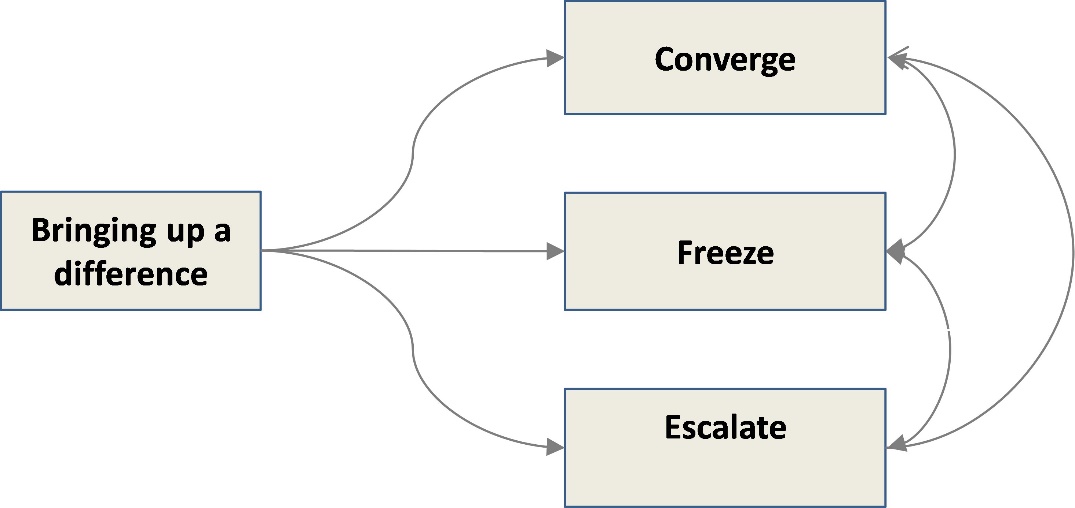

When pilots bring up a difference and make clear that they see things differently, this can lead to three different processes, as shown in the next drawing (Figure 6):

Three Conflict Processes Resulting from Raising a Difference.

When pilots converge, they come to an agreement and reach the sweet spot. If they do not succeed, they can freeze the discussion and focus on ending the flight together. When they escalate, a verbal and emotional explosion occurs. Bringing up a difference can lead to just one process or to a chain of several processes in succession. Raising a difference can, for example, lead to a short discussion to try to converge. If this is not successful, they can freeze by stopping the discussion until they have safely landed. During the debrief the discussion can be resumed and can lead to an escalation and, finally, to convergence.

The three processes are described in more detail in the following table by giving examples of the way the pilots speak, feel, work and report (Table 1):Table 1 Characteristics of Three Group Processes Concerning ConflictConverge Freeze Escalate Speak Discuss a difference

Understand each other

Admit an error

Make an excuse

Learn from each other

Park a difference

Choose words carefully

Become silent

Speak tersely

Subgroups talk together

Explode

Throw everything out

Speak loudly, shout, curse

Silence the other

Stop talking together

Body language Tacit consent

Cross arms

Turn away

Shrug

Sigh

Vibrating upper lip

Slamming doors

Throw a book

No handshake at parting

Feel Relieved

Relaxed atmosphere

Fraternal, close

Laugh

Work with pleasure

Go home satisfied

Tense atmosphere

Irritations, annoyances

Something is brewing

Control emotions

Little laughter

Go home dissatisfied

Hostile atmosphere

No inhibitions

Emotions reign

Crying

Being angry

Get emotions out

Work Focus is on work

No distraction, no focus on each other

Execute roles widely, exceed role description

Help each other

Work strictly according to standard procedures

Execute role strictly to prevent criticism

Distraction, focus on each other

Sit out the flight

Avoid contact

Stop collaborating

(Threat to) get off the plane, descend, cancel the flight

Refuse to work together on future flights

Report Inform higher management

Complain officially

Write a report

In dangerous situations like conflict, three basic human reactions are distinguished: fight, flight and freeze. Freezing in the pilot context signifies stop, look and listen. However, when pilots freeze, they do not stop working but continue by working strictly according to the standard operating procedures (SOPs) and divert their attention away from the person involved to ending the flight safely.

Escalation is not necessarily an undesirable process. It seldom happens during the flight and is postponed as much as possible to the debriefing on the ground. It can result in an improvement of procedures when it is reported to higher management.

The most desirable of the three processes is converging as this leads to the sweet spot of conflict and is a learning experience for all parties involved. Crucial for this success is the way the difference is brought up.3.4 Tactics Pilots Use to Converge and Reach for the Sweet Spot

Raising differences in such a way that the sweet spot of conflict is reached – understanding each other, interpreting the different perspectives, and coming to a common insight and viewpoint without undesired effects – calls for the use of communication techniques. Pilots are conscious of their conversational choice points and use different approaches such as humour, asking questions and paradoxical interventions.

Humour: Humour is a very effective way to raise differences, as an issue can be brought up without making it heavy and personal. By presenting someone a mirror in a funny though respectful way, the interaction remains light and easy. Every joke contains some truth and contains a message that can be transferred without becoming very serious. This approach can also be used in the presence of other people.

Asking questions: Asking questions is another effective approach that is used to make each other think about their motives and deeper interpretations. Asking why do you think, say or do this makes others reorientate themselves. A question is not an attack and leads to another type of discussion, other than blaming. It also allows persons to self-correct when they are in error.

Paradoxical remarks: Paradoxical or puzzling remarks disorient others, and they have to completely rethink what is happening. For example, paying a compliment when criticism is expected can stupefy someone and lead to introspection and reconsideration of ongoing actions.

Pilot feedback: In aviation, an expression has emerged that works as a stoplight. When a pilot says ‘I am uncomfortable’, this is a signal that everybody has to step back and reconsider what is happening. It also means that all attention should rivet on work itself and that blaming of each other should be avoided.

The chance of success also increases if a constructive climate has been established in the first instance. -

4 Conflict Risk and Damage Control

Crews make use of two work systems regarding hierarchy. Both systems are needed, and their alternation carries risk of conflict. However, captains learn to alternate them without causing conflict, and these tactics are also described.

4.1 Two Work Systems in the Cockpit: Power-with and Power-over

A flight crew is one of the most hierarchical teams in organisations and can be recognised by the golden and silver stripes on the uniforms of crew members. In the cockpit, three roles can be distinguished: the captain, who has three golden stripes; the first officer or co-pilot, who has two golden stripes; and the second officer, who has one golden stripe. A second officer is usually present on international or long-haul flights, where more than two crews are required to allow for adequate rest periods for the crew. Cabin officers also have a strict hierarchy consisting of at least a purser and a flight attendant. More ranks are present in aircraft that have a business and economy class. On international and long- haul flights, crews are usually large and have two pursers, the senior of which has the lead over the cabin crew and reports to the captain. The number of crew members on a flight varies from three to thirty. Larger crews have between eight to ten different ranks in their hierarchy.

According to the law, the captain has the ultimate responsibility and authority in the aircraft, as soon as the doors are closed. He is responsible for the crew, passengers and goods on board and is authorised to take all necessary decisions. Onboard, he can even determine whether birth or death took place and marry or handcuff persons. Although the law gives ultimate authority to the captain, he is still a human being, capable of making mistakes. As captains are also fallible and have to monitor and correct each other, crews have two different work systems that are called ‘power-with’ and ‘power-over’, with the following characteristics (Table 2):Table 2 Characteristics of Power-with Versus Power-over Work SystemPower-with Power-over Basic assumption We are equal and all have expertise We are unequal, and the leader knows best Leadership The role of leader and follower can alternate The roles of leader and followers are fixed Situation When problems are unknown and complex When time or consensus is lacking Knowledge Create new knowledge by considering all perspectives The leader imposes his knowledge on the group Type of conversation Power-free dialogue, joint interpretation of the situation Leader instructs direct reports and imposes his viewpoint Effect on collaborators Corresponds with the human need to be included, appreciated and have some control Is experienced as a form of regression, installs apathy, and is only accepted in crises The power-over work system equals the hierarchy in which there is a fixed leader who is supposed to know best and who imposes his will on the crew. This work system is necessary not only because the law requires that the captain has the final responsibility for what happens in an aircraft but also because time constraints can hinder more complex forms of decision-making and because more complex group analyses and discussions do not necessarily lead to consensus. In those cases, any decision is better than no decision at all, and it must be clear who has to take it.

As all human beings, including captains, are fallible, crews also have a power-with work system. In this system, all crew members are invited to signal what they think is important to bring in, so the collective intelligence gets mobilised. In the back of the aircraft, crew members can see things that can be important and that should be known in the cockpit. The same applies to passengers as they too can perceive events that have to be reported. To stimulate all parties to bring in their observations and viewpoints, a power-with work system is necessary. This work system can flourish only if crew members and passengers are willing to do so. Therefore, the captain lowers the threshold for participation and tries to avoid being put on a pedestal.

4.2 Synchronicity to Get the Best of Both Worlds

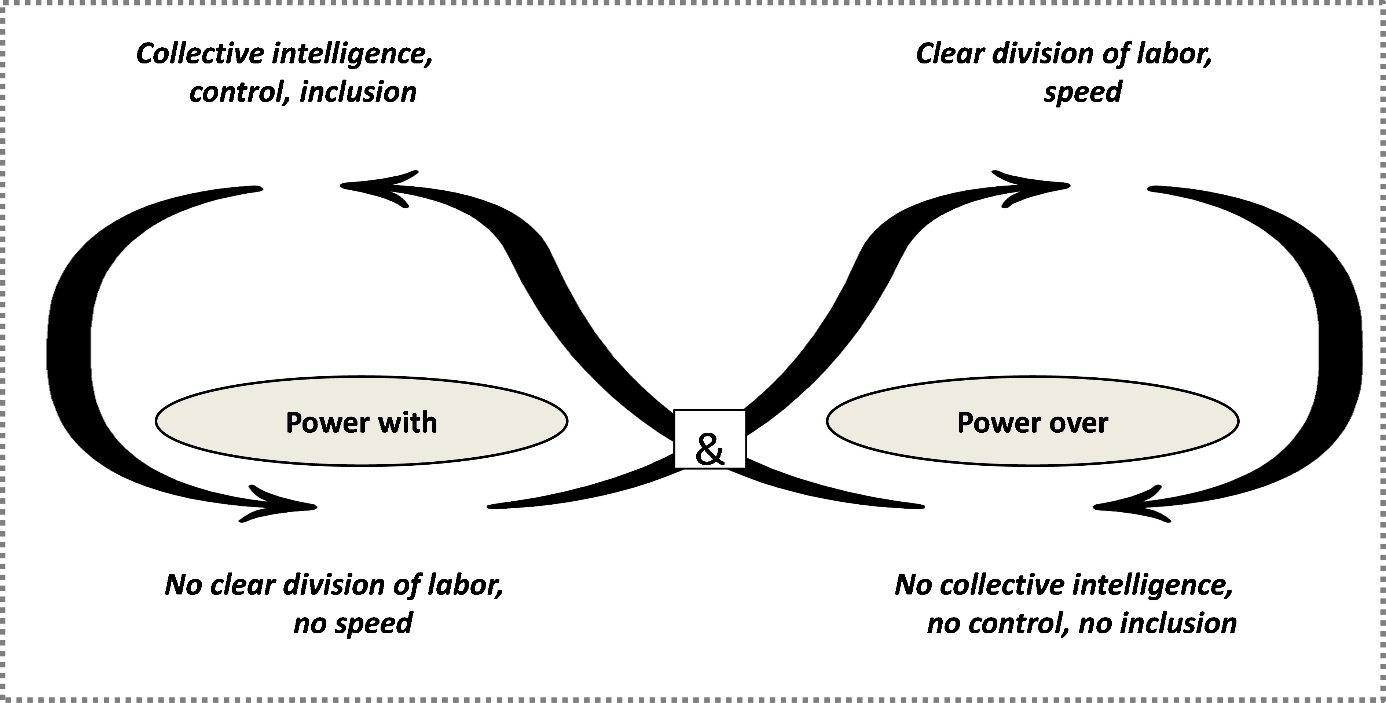

Although the power-with work system is preferable in view of its mobilisation of collective intelligence, crews cannot operate without the power-over work system. When time is short or consensus fails, the captain has to impose his will. So rather than being a case of one system versus another, both work systems are needed as they both have significant advantages, as shown in the following drawing:

Polarity Infinity Loop of Power-with and Power-over.Johnson B. (2014). Reflections: A Perspective on Paradox and Its Application California to Modern Management. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science,50 (2), 206-212. doi:10.1177/0021886314524909.

Although both work systems are needed for successful crew operations, they also have disadvantages. Mobilising the collective intelligence in crews by inviting all members to bring in their perspective stimulates optimal decision-making while crew members feel appreciated, included and in control of their operations. However, this approach is also time-consuming and can blur the authority structure. Captains are challenged to maximise the advantageous upside and to minimise the disadvantageous downside of both approaches, as visualised in Figure 7. Captains do this by alternating both systems in time. This might make you think of ‘situational leadership’, a leadership theory developed by Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard, who promote the idea that leaders have to adapt their style to the maturity of their followers. However, this idea does not apply in the cockpit because all pilots know how to fly, as the captain could develop a health or other problem. If the captain becomes incapable of working, the co-pilot can end the flight alone and land the aircraft safely. Although the alternation of both work systems by captains is a form of situational leadership, the situation here is not the maturity of the follower but the time available for decision-making. Collective decision-making is preferable but not always possible. It is the alternation of both approaches that constitutes the most important risk area for conflict.

4.3 Alternation as a Major Risk Area for Conflict

When the captain imposes his will and leaves the open power-with climate behind, he risks eliciting conflict. Whenever he gives an instruction, corrects someone or enforces his viewpoint otherwise, conflict can arise. An analysis of more than 80 cases at KLM identifies this to be the most important cause of conflict. Why do crew members not simply accept the captain as the boss? In aviation, an authoritarian leadership style is a sensitive subject as captains are human beings and make mistakes..

4.4 Managing Alternation Without Eliciting Conflict

Captains have developed several tactics to navigate between the two work systems, power-with and power-over, either without eliciting conflict or halting it at an early stage. The following are examples of the tactics used:

4.4.1 Ask the Other Person What Has to Be Decided

When the exchange of conflicting viewpoints does not come to a natural conclusion, captains might just ask the co-pilot, purser or other person involved in the disagreement what has to be decided. The captain can introduce his question by sharing his dilemma: On the one hand, there are these arguments…on the other hand these…. The other person might produce a creative solution, and if this is within the captain’s window of safety, he will agree to it.

4.4.2 A ‘Good Story’

When a captain imposes his viewpoint to end a discussion and comes to a decision, he is supposed to come up with a ‘good story’. A good story stands for the logical flow of arguments that make his decision plausible, reasonable and credible. This story has to integrate all the arguments that have come to the table to show that these have been heard and considered. It also has to show how these arguments have been weighted and why he judged some more important than others to come to his decision.

4.4.3 I Will Explain My Decision Later….

When time is short and a decision promptly needed, captains will impose their will and say that they will explain later. ‘Later’ is probably during the debriefing on the ground. After a safe landing, he can come up with his story and explain the arguments of his enforced decision.

4.5 Damage Control When Conflict Arises

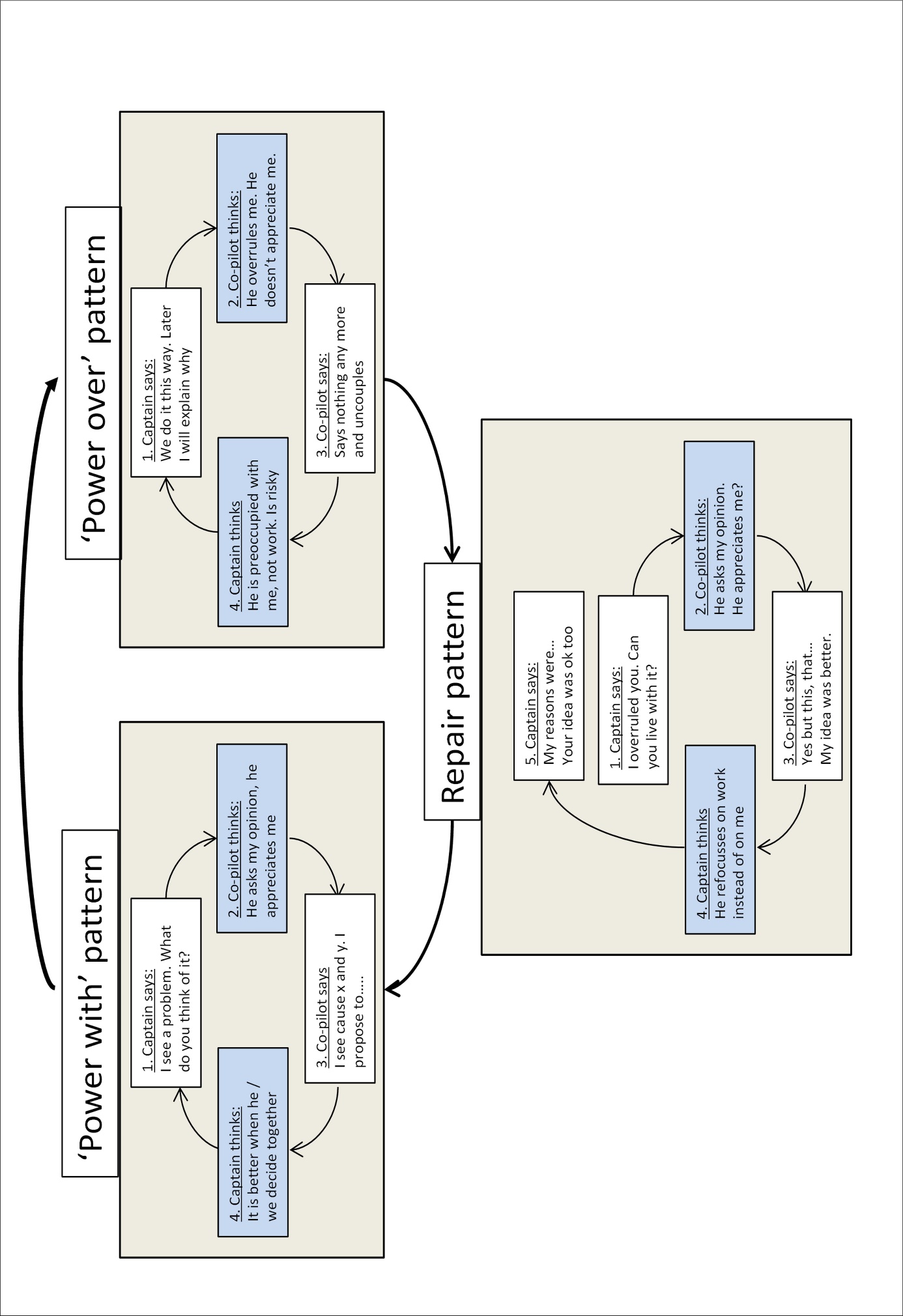

If the co-pilot, purser or other persons involved are not convinced of the arguments and the atmosphere starts to get tense, captains have several possible ways to manage the ensuing conflict. The first is to restore the relationship by addressing the fact that they had to impose their will. How they do this is visualised in the next drawing (Figure 8):

Repair Process When Conflict Starts.

The drawing shows three processes: power-with, power-over and repair. The example concerns a captain and a co-pilot. After the captain has had to overrule the co-pilot, he realises that the co-pilot is a human being and might not like to be overpowered. He tries to repair the relationship by addressing the fact that he has enforced his will and asks if the co-pilot can live with this. This question allows the co-pilot to express his frustrations. This personal interest of the captain and the venting of his emotions can defuse the tense atmosphere. This chance increases if the captain can also appreciate the point of view or idea of the co-pilot.

If the repair process is not successful, two other processes are still available to manage the process –freezing and escalating. To end the flight together safely, the situation can be frozen, as explained earlier. All crew members involved continue working strictly according to standard operations. Although this is less safe than working in an open and constructive atmosphere, it is the best they can make of it. In case the subject is considered very important by one or all the persons involved, the conflict can be escalated. Escalation is usually an emotional process and refers to emotional and verbal outbursts. However, if all parties involved are so convinced of the arguments and the importance of the issue at hand, they can strive for rational escalation. This involves bringing their case up to higher levels in their organisation and asking for their superiors’ viewpoint. This is not necessarily a negative process and can lead to the improvement of operational procedures. -

5 Universal Mediating Skills for Organisational Settings

The way pilots reach for the sweet spot of conflict has attracted the attention of other professionals like doctors, lawyers, accountants, board members, etc. After numerous workshops with these other professions, three universal mediating skills can be distinguished in work settings: working with reality, emotions and power.

5.1 Working with Reality

The sweet spot of conflict is an optimal point or moment in which all perspectives come to the table, are exchanged and studied in such a way as to bring out the best insights owing to deep and sound interpretations. In work situations, this is the basis for a high level of performance. Pilots are not the only professionals to strive for a high level of performance. All teams, boards and organisations also do so. Their leaders will be able to reach this optimum if they embrace the following convictions and guidelines:

All professionals are fallible and make mistakes. High rank and/or much experience do not protect against mistakes.

All perspectives can be valuable and have to come to the table. Participants in all ranks can notice details or beginning problems without understanding their importance. They have to be invited to share their information.

Focus on the phase before opinion. What do people see? What do they hear? What do they feel? These are the building blocks of their reality that they are not always conscious of.

Create a collective mind by connecting the parts of reality perceived by all.

Make use of the safety window: the difference between good and excellent solutions can be very personal and need not be addressed. But unsafe work situations have to be prevented or ended at all costs.

Reaching for the sweet spot of conflict is of interest not only to management but also to all members of aircrews, who share responsibility for creating a good climate in which to fly safely.

The preceding convictions are characteristics of post-formal thinking.1x Sinnott J. (1998). The Development of Logic in Adulthood: Postformal Thought and Its Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. The essence of post-formal thought is the ability to work with several truths. The knower sees that knowing involves a region of uncertainty in which, somewhere, the truth lies. All knowledge and all logic are incomplete; knowing is partly a matter of choice. According to Sinnott, adults might develop post-formal thinking because they regularly encounter complex problems with unclear structures. These problems lack a single cause or a single best solution but have multiple ways out.5.2 Working with Emotions

Working with emotions or emotional labour is a second mediating skill that pilots share with other professionals in organisations. The concept originates from Hochschild.2x Hochschild A.R. (2012). The Managed Heart. University of Press. In 1983, she conducted research into Delta Airlines and found that cabin attendants are trained in manifesting positive feelings towards passengers. She concluded that in addition to physical and knowledge work, there is also emotional work. This aspect of work was then also seen in other professions. For example, bailiffs must evoke negative feelings, catering staff must evoke positive feelings and judges must remain neutral. Emotional work can take three forms:

Reading the emotions of others by deciphering body language – facial expressions, posture, voice, etc.

Influencing others in such a way that they get into the desired mood and start exhibiting the desired behaviour

Managing own emotions: not showing feelings, showing false feelings, transforming feelings with the help of breathing, thoughts or memories

Reading other people’s emotions is an important skill for pilots as they have to assess passengers and crew members. The same applies to managing other people’s emotions. They try to keep others happy and stress free so that they can do their job well. Managing one’s own emotions is focused on preventing ‘inner escalation’ and keeping one’s own emotions under control.

Most other professionals are less aware of their emotional labour, but when the concept is explained, they immediately realise that they also work with emotions. Emotions thus become a working instrument, just like knowledge or physical strength, and this contributes to the achievement of organisational goals.

According to the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions,3x Fredrickson B.L. (2004). The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367-1378. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1512. positive emotions broaden our awareness and provoke inquisitive and curious thoughts and activities, promoting learning. This contrasts with negative emotions, which narrow our consciousness and restrict our thoughts and actions. The pilots regularly speak of ‘tunnelling’, which refers to this narrowing of consciousness. They want to prevent ‘tunnelling’ in themselves and their colleagues because they need ‘a broad horizon’ to do their work well. According to Fredrickson, operating in the ‘zone of positive emotions’ is necessary for this.5.3 Working with Power

Most conflicts from the author’s PhD study are about power. Exercising authority, overruling others and egotism are the main sources of conflict. The exercise of authority is usually done by the captain when he instructs or corrects a crew member, but the reverse can also be the case. A crew member then uses his authority to correct the captain and does speak up. In this way, the ‘primal conflict’ in organisations has emerged as the most important source of conflict.4x Mastenbroek W.F.G. (2005). Conflicthantering en organisatie-ontwikkeling. Boom Uitgevers.

Organisations have many latent tensions that can be activated at any moment, including the tension between high and low. This dormant primal conflict can be activated when a captain exercises authority or a crew member makes his voice heard. It is about the contrast between control and autonomy: high wants to control low, and low tries to maintain or increase its autonomy. This basic tension occurs in all kinds of human systems, including teams, departments and organisations. It is about blind reflexes that are widely spread but experienced as very personal.5x Oshry B. (2007). Seeing Systems: Unlocking the Mysteries of Organizational Life. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

The workshops related to the author’s research showed that Dutch pilots are not the only ones who prefer consultation to imposition, knowing the risk of pilot error. Representatives of other professional groups and other cultures indicated the same preference. In general, people seem to prefer democracy to hierarchy, irrespective of their national culture.

Analysing formal and informal power and how it is dealt with to reach organisational goals is an important mediating skill in business. Making power discussable so as to bring the sweet spot of conflict within reach is also part of this but is not always easy. -

1 Sinnott J. (1998). The Development of Logic in Adulthood: Postformal Thought and Its Applications. Springer Science & Business Media.

-

2 Hochschild A.R. (2012). The Managed Heart. University of Press.

-

3 Fredrickson B.L. (2004). The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367-1378. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1512.

-

4 Mastenbroek W.F.G. (2005). Conflicthantering en organisatie-ontwikkeling. Boom Uitgevers.

-

5 Oshry B. (2007). Seeing Systems: Unlocking the Mysteries of Organizational Life. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Corporate Mediation Journal |

|

| Article | How Pilots Reach for the Sweet Spot of Conflict |

| Keywords | positive work climate, communication, beginning conflict |

| Authors | Eva van der Fluit |

| DOI | 10.5553/CMJ/254246022022006001002 |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Abstract Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

Eva van der Fluit, 'How Pilots Reach for the Sweet Spot of Conflict', (2022) Corporate Mediation Journal 3-13

|

Both on the ground and in the air, attention to detail can make all the difference between safety and disaster. Focused on pilots, Eva van der Fluit investigates what is needed in order to align the perspectives of all professionals they collaborate with so as to facilitate solid judgment and sound sense-making as the basis for their actions. This can lead to disagreements and conflict, which is not necessarily bad when they can manage, constructively, the pinnacle of differing paradigms at crucial moments. This can be defined as the sweet spot of conflict. This spot represents the essential moment at which all perspectives come to the table, are exchanged and lead to new insights. It takes special skills to manage such a process, many of which can be seen as mediation skills. If pilots, most often the captain, can successfully keep the communication process focused on the content and if they do not make it personal, the sweet spot may result in achieving a coordinated outcome, supported by all involved. The way pilots manage what is known as beginning conflict (as distinct from escalated conflict) has attracted the attention of other professionals such as doctors, lawyers, accountants and board members. Even at the lowest level of an organisation, important lessons may be learnt from the best practices developed in the airline industry. |