-

1 Introduction

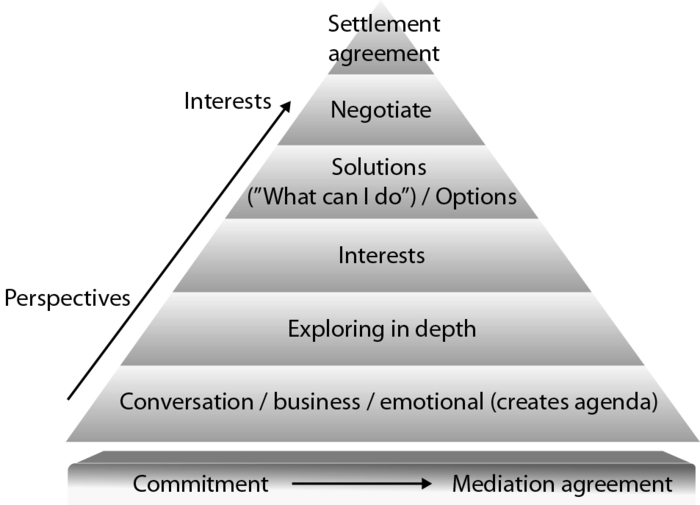

The Mediation Process© Mediations are of all sorts. They may be about healing, but also about little more than dealing. If a conflict is about more than just miscommunication, negotiation will be an element of the process. Not only corporate conflicts but also very personal conflicts may end up in cold-blooded negotiation. Business negotiations may be hard, but at a different level, the fight over who will get to keep the cat is not so simple either. The negotiation about the content of a conflict will formally occur towards the end of a mediation, after introduction of the mediation process itself at the intake or the signing of the mediation agreement, opening statements, investigating interests and options (see Figure 1).

Mediations are of all sorts. They may be about healing, but also about little more than dealing. If a conflict is about more than just miscommunication, negotiation will be an element of the process. Not only corporate conflicts but also very personal conflicts may end up in cold-blooded negotiation. Business negotiations may be hard, but at a different level, the fight over who will get to keep the cat is not so simple either. The negotiation about the content of a conflict will formally occur towards the end of a mediation, after introduction of the mediation process itself at the intake or the signing of the mediation agreement, opening statements, investigating interests and options (see Figure 1). Informally, negotiation may take place from scratch, as early on as when considering to opt for mediation. The selection of the mediator, time and place of the mediation, who will pay the mediator’s fee, who will participate, issues like carve outs of the confidentiality covenant and even who will begin at opening statements may all be negotiated issues. These are minor issues compared with the subject matter of the conflict. Nevertheless, sometimes as an expression of the real problems between parties concerned (e.g. lack of trust, self-confidence or considered strategy), haggling about those minor issues may absorb a lot of time and energy. A party may even pretend to agree to mediation, but make certain not to come to terms about the choice of mediator or about logistics, only to avoid having to enter into serious negotiation about the real issue at stake. Or, if forced by a mediation clause in a contract, parties may participate in a mediation process only to frustrate any progress and run the other way fast, stating they have attempted mediation but could not find a solution. When serious parties sincerely attempt to resolve their issues, they most likely will get to a negotiation phase in the mediation about the substantive content of the problem. The question can arise then, who will make the first offer or first demand? Making this first offer is called ‘anchoring’ or dropping an ‘anchor’ in negotiation jargon. This article investigates various aspects of anchoring. Does an anchor influence the outcome of a negotiation? Is it smart to drop an anchor early on or is it better to wait? How to respond to an anchor dropped by a counterpart? How to frame an anchor? The message of this article is that there are multiple ways of looking at anchors and dealing with anchors and that it would be a serious mistake not to be conscious of the theoretical and practical aspects of anchoring when entering into a negotiation. There is more to the theory and practice of anchoring than the often-proffered idea that it is almost always best to avoid being the one to make the first move.1x See, e.g. Lempereur A. & Colson A. (2016). The First Move, A Negotiator’s Companion. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, p. 116. It is further discussed what role the mediator can play when it comes to first offers or first demands. The mediator is there to facilitate the process. How to facilitate the parties who want to start negotiating but are reluctant to be the first to show their hand?

-

2 Zone of Potential Agreement

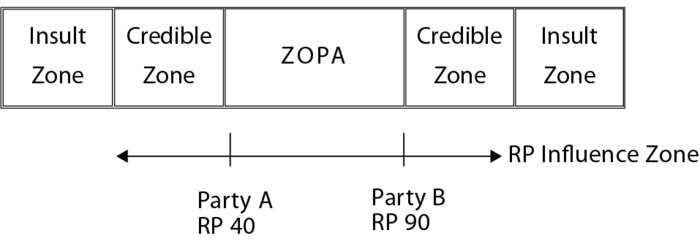

Negotiation has much to do with establishing what is called the zone of potential agreement (‘ZOPA’, see Figure 2).

Zone of Potential Agreement

The ZOPA is determined by the space between the reservation price of both parties. The reservation price ("RP") is ‘the walk away’ price. The reservation price of the purchaser is the amount he or she is willing to spend as a maximum in order to conclude a transaction. The reservation price of the vendor is the amount he or she will at least want to receive as a minimum in order not to refrain from executing a transaction. As shown in Figure 2, there may be a credible zone, within which an offer or demand price can be mentioned that is ‘just this side of crazy’. Beyond that there is what is called an insult zone, which is determined by ‘the other side of crazy’. If the ZOPA is, for example, between 40 and 100, negotiation will further have to lead to a compromise that may be anywhere between 41 and 99. Finding out the reservation price of the counterpart is important in negotiation talks. Certain scholars therefore feel it is best not to make a first offer because it may give away – give or take certain margins to be added or deducted – where their reservation price might be. That is why an experienced negotiator like Jim Camp recommends ‘no talking, or less talking’: “If you cannot control the motor mouth, you’re eventually going to say something you’ll regret for the duration of the negotiation; don’t spill your beans, not in the lobby or anywhere else.”2x Camp J. (2002). Start with No. New York: Crown Business, p. 154.

The strategy, which is aimed at asking as many questions as one can, is especially indicated, I believe, in more complex negotiations, that is, where it concerns multiple topics (e.g. negotiating a joint venture or merger agreement). As in mediation, it pays to find out more about the real interests of the other party. In more complex situations, where the outcome will be a package of more topics, it is essential to find out as much as one can about the full picture of the desired result on the part of the other party. This means one should not come with a first offer too quickly. One can then later see if by means of logrolling (trading what is more important for one with what matters less to the other) a transaction can be concluded. In simpler situations, for example, where it concerns only one object and in the end it is just about the price for that one object, it will be equally useful to set out on a fishing expedition about all sort of details, but room for logrolling will be limited, if any. This means that the discussion will be more concentrated on only one topic and therefore often will (have to) remain more superficial. It matters in all cases to discover what motivates someone to want to do a transaction. Is it, for example, due to financial distress or because someone is keen to engage in a subsequent transaction with someone else? Questions pertaining to the motivation of the counterpart will most likely belong to the first introductory exchange of pleasantries. Think of visiting a house for sale. The first question will be why the owner is selling the house? Is there a change of job or a divorce, or has a new house already been bought?

How well informed is the other party about value and options? To learn more about these so-called negotiation parameters may make a difference when it comes to determining whether or not to make a first offer. Are there any general rules where it comes to make or not to make a first offer? -

3 Theory

There is research that suggests that whichever party – the buyer or seller – made the first offer obtained a better outcome in negotiation about a price (in distributive negotiation).3x Galinsky A.D. & Mussweiler T. (2001). First Offers as Anchors: The Role of Perspective-Taking and Negotiator Focus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(4), 657-669. Other research also found a correlation between anchoring and negotiation outcomes.4x Orr D. & Guthrie C. (2006). Anchoring, Information, Expertise, and Negotiation: New Insights from Meta-Analysis. Ohio State Journal on Dispute Resolution, 21, 597-629. It was furthermore found that anchoring did influence mock jurors.5x Among others, Chapman, G.B. & Bornstein B.H. (1996). The More You Ask For, the More You Get: Anchoring in Personal Injury Verdicts. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 10, 519, 525-528 and 532-33; and Hastie R., Schkade D.A. & Payne J.W. (1999). Juror Judgments in Civil Cases: Effects of Plaintiff’s Requests and Plaintiff’s Identity on Punitive Damage Awards. Law & Human Behavior, 23, 445 and 463-465. The findings of this and other research on anchoring, however, cannot be taken as an absolute. It is important to bear in mind that many other factors than anchoring may influence the outcome of negotiations or judgements. Research takes place in laboratory situations and that may have an impact on the behaviour of participants in the project (experimental demand). Parties may respond and act differently in real-life situations. In real life, there are many factors that may influence a negotiator’s judgement and decision making, and it is most often a combination of those factors. Anchoring is just one of the factors.6x See Korobkin R. & Guthrie C. (2006). Heuristics and biases at the bargaining table. In A.K. Schneider & C. Honeyman (Eds.), The Negotiator’s Fieldbook, The Desk Reference for the Experienced Negotiator. Washington: American Bar Association, Section on Dispute Resolution, pp. 351-363. There may be, for example, influence through availability. This so-called availability heuristic can cause a negotiator to evaluate his or her options on the basis of the readily available information or feelings, whereas more cognitive effort, statistical data or other research might have led to another judgement or decision.7x See Kahneman D. (2011). Thinking Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books, pp. 131-137. In negotiation, in general, homework and preparation are key. Another factor can be self-serving evaluations. This means that individuals often judge uncertain options as more likely to produce outcomes that are beneficial to them than an objective analysis would suggest. Telling is the example that people when asked, overestimate their relative contribution to housework, making their combined estimates exceed 100%.8x Ross M. & Sicoly F. (1979). Egocentric Biases in Availability and Attribution. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 37(322), 324-326. Other factors involved in decision making may be the framing of choices. It makes a difference whether or not one emphasises only the expected value of a choice to be made, or refers to the possible outcome as a gain or a loss relative to a reference point. A clear example is rendered by settlement negotiations in a court case. Winning – which is hardly ever certain – will come at a cost for registration and lawyer’s fees, investment in time and energy and distraction from other (even) more fruitful pursuits. A poor settlement may be better than a good trial. The difference in framing the options becomes clear in the difference between ‘there is a good chance of winning’ or ‘it is possible to lose’ a case. Also the relevant position of a party may be a factor. Agreeing to receive a lesser outcome than possibly to be gained in a trial by someone without means may not be the choice of a well-to-do plaintiff. The same applies to negotiation. A counterpart may be in need of money or otherwise be forced to conclude a transaction. If the counterpart is not under any pressure to conclude a transaction, the situation is different. Alternatives therefore play an important role. It matters what the best alternative to a negotiated agreement (“BATNA”) is for the other party. The cost of failing to reach an agreement may be outweighing the cost of accepting a sub-optimal result. Emotional attachment to goods (endowment effect) or the attachment to a trusted situation (the status quo bias)9x Korobkin & Guthrie (2006), pp. 292-297. can be another influence that may affect the outcome of a negotiation. The saying that in negotiation ‘emotions can only be expressed in monetary terms’ is alien to mediators, but may on the other hand carry a certain weight when it comes to translate emotional aspects into a negotiated outcome of a conflict. That is, if there has to be a negotiated outcome, because emotional aspects can also get in the way of reaching any kind of agreement.

As said, anchoring is one of the factors that may be of influence on a negotiator’s judgement and decision making. This may particularly be the case – which will often be – where there is not a known objective value available of an object or situation. Even market research, comparison with prices fetched for comparable objects, valuations by experts, and other means do not set aside many of the factors indicated above that may exercise influence on a negotiated outcome. Anchors also may weigh into a negotiated outcome in the midst of all circumstantial factors.

Since it is not always easy to determine an exact monetary value of things, a negotiator can attempt to affect the quality of a proposed agreement by dictating the content of an anchor. In business negotiations where monetary values are usually the bargaining currency, dropping an anchor that appears only remotely related to the subject of the negotiation may affect a counterpart’s judgement, particularly when there is some logic added in terms of an explanation why the amount of the anchor would be justified. Ambiguity about monetary values is the friend of bias and hence of anchoring. Bias is the conscious or subconscious influence of experiences, information, context or events on cognitive feelings (feelings about knowing). Past experiences may consciously but also subconsciously influence our perception by associative memory (“priming”). Our actions and emotions can be primed by events of which we are not even consciously aware.10x Korobkin & Guthrie (2006), pp. 52-59. Priming is well explained by the example of encountering a stranger on an otherwise empty street at night. Is it someone to fear? You are likely to have a different level of comfort with the approaching person if you have just come from seeing a horror film than if you have just seen a romantic comedy.11x Gilovich T. & Ross L. (2016). The Wisest One in the Room, How to Harness Psychology’s Most Powerful Insights. London: Oneworld Publications, p. 84.

Important when it comes to anchoring is that – where many subjective experiences are used in judgements – these subjective experiences retain their potency only as long as the source of the influence is kept outside of the negotiator’s conscious focus.12x Schnall S. (2017). Social and Contextual Constraints on Embodied Perception. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(2), 325-340. In simple wording, anchoring will only have effect as long as the negotiator is not consciously aware of the cause of its effect. This underscores the importance of knowledge of the process involved in anchoring. Information and expertise can mitigate the effect of an anchor. It is relevant for negotiators and mediators to have a comprehensive understanding of what factors influence perception so that appropriate behavioural measures can be deployed.13x Id., p. 335.There are a number of theoretical accounts to explain why we would anchor.14x Lempereur & Colson (2016), pp. 602-605. The social implications theory posits that in social exchange we tend to believe that people who provide us with an anchor would only do so if the anchor conveyed meaningful information about the object under consideration. This leads us to believe that the true value will be somewhere in the vicinity of that standard, at least for our counterpart. This will particularly be relevant in cases where there is ambiguity about the value. Therefore – although an anchor may be extreme – it should not be so out of bounds that it is not credible (stay at ‘just this side of crazy’). An anchor serves as a kind of reference point or benchmark that influences our expectations about an item’s actual value. Another theory, the insufficient adjustment theory, has it that in cognitive decision making we first focus on the anchor and then make a series of dynamic adjustments towards a final estimate. Because these adjustments may be insufficient, the final answer is biased towards the anchor. The failure to adjust adequately has been attributed to uncertainty or to a lack of cognitive effort. Then there is the numeric priming theory. That theory assumes that once a numeric anchor is dropped, that number, even regardless of its relevance to the subject in question, influences one’s estimates.15x Strack F. & Mussweiler T. (2003). Heuristic strategies for estimation under uncertainty: the enigmatic case of anchoring. In G.V. Bodenhausen & A.J. Lambert (Eds.), Foundation of Social Cognition: A Festschrift in Honor of Robert S. Wyer, Jr. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., p. 85. Most of the time we make insufficient adjustments away from an anchor. Finally, I mention the information accessibility theory.16x Gilovich & Ross (2016), pp. 81-83. The idea is that when confronted with an anchor, we engage in a kind of explicit or implicit hypothesis testing of the accuracy of the value of the anchor. By doing so – looking for evidence, consistent with the hypothesis – even when we quickly reject the hypothesis, the fact that we have taken it seriously for a moment as potentially true may cause to affect our judgement (priming).

Certain care has to be taken not to consider any of these theories as an absolute truth either. None of the above-mentioned theories are conclusive. Each explains, at least in part, why we are susceptible to the particular cognitive phenomenon that anchoring seems to influence our judgement.17x Galinsky & Mussweiler (2001), p. 605. It is ultimately as simple as the subliminal effect of offers, positioning and packaging played out daily in our lives to influence buying decisions in supermarkets, car showrooms and many other environments. We just don’t consciously realise we are being anchored in the art of persuasion.18x Leathes M. (2017). Negotiation, Things Corporate Counsel Need to Know but Were Not Taught. Alphen aan den Rijn: Wolters Kluwer, p. 97. -

4 Applied Science

Margaret Neale and Thomas Lys19x Neale M.A. & Lys T.Z. (2016) Getting (More of) What You Want. London: Profile Books, chapter 7. analysed the various considerations determining the timing of first offers. Their conclusion is that the question to make or not to make the first offer is not a simple binary question. In all cases, it is important to analyse the particular situation, one’s own behaviour and the behaviour of the counterpart to determine the best course of action. In their workshops they asked participants (executives, [under]graduate students and their parents) what they believed to be the best approach in negotiations, to make the first offer or to wait and receive the first offer from the counterpart. An overwhelming 80% of the participants preferred to receive rather than to make the first offer. The explanation was in line with a widely held belief that waiting for the first offer is rendering a competitive advantage because the first offer will give away information. It will tell the receiver something about the position of the counterpart. Another consideration is that making the first offer oneself is taking the risk that the offer is too high, giving away more value than would have been necessary. Especially when a first offer is accepted straightaway by the counterpart, the feeling will remain that there could have been more to gain. This is why in case one receives ‘an offer one cannot refuse’ the advice is to turn that offer down. Negotiate just a little further in order to take away the feeling of the counterpart that they sold out to cheap.

The analysis made by Neale and Lys turned out that nevertheless in 75% of cases it was recommendable to make the first offer. It all begins – like always in negotiation – by preparation. The more knowledgeable one is about comparable objects or situations and the counterpart, the better equipped one is to negotiate, drop anchors and respond to anchors. Negotiation has a lot to do with information asymmetry. Anchors are more effective the less precise the knowledge of the counterpart is, or, in general, when ambiguity about the value exists. In a well-known study, it was found, however, that even in an information-rich environment experts were influenced by anchors.20x Northcraft G.B. & Neale M.A. (1987). Experts, Amateurs, and Real Estate: An Anchoring-and-Adjustment Perspective on Property Pricing Decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 39, pp. 84-97. Denying that they had been influenced by list prices, real estate professionals in a real-world setting proved to have been affected in their physical appraisal of property by differing list prices they were given in otherwise identical information brochures.In many situations – unlike a widely held belief – it may be recommendable to make the first offer. To a large extent, the choice is to be determined by the level of information over which one avails and/or the counterpart avails. Each situation is different. If one avails over information, the counterpart perhaps does not have, and it may be better to ask the counterpart to mention a price first. With the Internet, however, the extent to which information asymmetry may occur is no longer to be overestimated. Even at a simple flee market, chances to find a Rembrandt or Rolex without the vendor having at least an inclination of a value, for the most part, are slim.

-

5 The Pawnbroker

The expression of the belief that it is not recommendable to make the first offer can be seen in the televised negotiations in pawn shops (Posh Pawn, Hardcore Pawn, Pawn Stars).21x See <www.google.nl/search?safe=active&ei=EKERWsTVD4W3aZ3qgdgK&q=pawn+tv+programs&oq=Pawn+TV+Programs&gs_l=psy-0.0i19k1j0i22i30i19k1l8.4922.13615.0.15687.8.7.1.0.0.0.146.673.6j1.7.0....0...1.1.64.psy-ab..0.8.677...0i8i13i30k1j0i8&gws_rd=ssl>. The pawnbroker never is the one to give away a price indication. He always starts by asking the person bringing an object into the shop whether he or she wants to pawn or to sell it and why it is being offered. Next the pawnbroker inquires what the person has in mind to get for it. These questions help to give the pawnbroker an indication whether there is an information asymmetry and what the extent of it is. He only enters into a negotiation – unless he already knows from experience – after having investigated the value of comparable goods on the Internet or even seeking an expert opinion on the value. After having also estimated the likelihood of reselling the goods, a very low anchor is dropped, allowing for one or two small adjustments to reach the reservation price of the owner or the pawnbroker. The counterpart then tries several times to still up the offer of the pawnbroker, often to find him- or herself having concluded the transaction at a price far removed from the price demanded in the first instance. What is happening in the negotiation in the pawn shop is illustrative for negotiation in many other situations: the pawnbroker trying to obtain as high a level of information as he can about his own negotiation parameters (the Internet search, expert opinion, demand for the object in the market and reservation price). His level of information about the negotiation parameters of the client remains relatively low (‘You want to pawn or to sell the item?’ and ‘How much do you want to get for the item?’). The client knows relatively little about the pawnbroker’s negotiation parameters. This would be different if the client were to know, for example, how much value the item on offer really represents for the pawnbroker and how much value he places on obtaining it, or, how much the pawnbroker is in need of turnover. If the client were to know these things, he or she would have a high level of information about the pawnbroker’s negotiation parameters. Since this information is generally not accessible for the client, the information asymmetry is in favour of the pawnbroker. It is all about how much each party in a negotiation knows about their own negotiation parameters and about those of their counterpart. It is important in every negotiation to establish whether (i) you know little or more than little about the counterpart’s negotiation parameters (i.e. avails over much knowledge, a good bargaining position, BATNA, and what have you) and (ii) little or more than little about your own negotiation parameters. In case you know little about your own negotiation parameters (e.g. not certain about the value of an item, where to obtain more information, how sellable the object may be), irrespective of how much you know about the negotiation parameters of your counterpart, it is best to refrain from making the first offer. In the event you are aware of your own negotiation parameters, it is better to make a first offer irrespective of whether the same applies to the counterpart.22x Neale & Lys (2016), p. 116.

The recommendations mentioned hereinabove make sense. If anchors work best in case of ambiguity, a low level of information about the own negotiation parameters on the part of the counterpart make a first offer have more impact, in addition to being harder for the counterpart to counter the information advantage. If the counterpart is equally well informed, waiting for him or her to make the first offer is not going to make things better, but risks to be confronted with a high anchor. Countering a high anchor puts one – if one is not very careful – in the defensive and so does work as a real anchor in the discussions. The effect of an anchor is that the party on the receiving end of that anchor will start to focus more on his or her own reservation price. The effect on the one dropping the anchor is that this party sets the bar at a higher level than the reservation price and so strives for the aspiration price. This is also known in negotiation jargon as ‘LIM’: like, intent, must. ‘Must’ is the reservation price. ‘Like’ is what one preferably will get. ‘Intent’ is striving for ‘like’ (the aspiration price). This may help not to show any relieve in body language, facial expression or otherwise when a price is tabled which in itself would allow the transaction, but is not the very best (‘like’). An anchor may serve as a benchmark. Hence the recommendation is to make an anchor as extreme as one can while still getting the counterpart to respond. Do not make what is called ‘an insult offer’, which will make the counterpart walk away immediately. Make it ‘just this side of crazy’, add a justification and make the numbers contained in the first offer appear precise rather than rounded (even if no such accuracy objectively exists).23x Leathes (2017), p. 108. Neale and Lys maintain that, for example, houses sell for more when their listing prices were precise ($1,423,500) rather than round ($1,500,000) even when the round number was larger than the ‘seemingly’ precise number!

-

6 Lifting an Anchor

What about the other side of that spectrum? How to respond to first offers and how to protect oneself against the effect of anchoring? As we have seen, it was found that preparation, information (i.e. expertise) and consciousness (mindfulness) of what may be going on can have a mitigating effect on the workings of anchoring. Yet, even then, it is difficult not to undergo some influence of anchors. When an asking price is, for example, 1,000 euros, it will take a lot of work to negotiate that amount back to, say, 100 euros. All the theories mentioned above come into play. Depending on the kind of object under negotiation, one may feel embarrassed with respect to the social implications for the relationship with the counterpart to keep continuing to push the price down, although this may be different in different cultures.24x Leathes (2017), p. 109. They deservedly make a distinction for cultural differences. For example, they observed that the first offers and counteroffers that are given by carpet sellers in Istanbul are quite different from the equivalent offers and counteroffers by a carpet seller in Zurich (even when the sellers were both of Turkish origin). Depending on the (accessibility to) information available, the result of numeric priming may make one end up with too little adjustment in counteroffering or judgement may be blurred by the information asymmetry in combination with the cunning explanations of a higher value by the counterpart. So, how to deal with first offers in practice? It is time to look at some of my own experiences from over 40 years of negotiating as an attorney at law on behalf of clients and myself. The former, by the way, is much easier done than the latter.

One recommendation is not to ask the party who dropped the anchor to elaborate on how one arrived at the figure of the anchor. This will only stimulate an effort to dig deeper into the trench of reasonability of the arguments and the figure mentioned. This is only different if one avails over so much subject matter expertise that it is possible to materially contradict every argument mentioned in support of the anchor.

In other cases, it is best to ignore the anchor and focus the discussions on one’s own negotiation parameters. If that does not have the desired effect, the response may be an equally extreme anchor (‘just this side of crazy’). I remember one negotiation where the counterpart was the first to drop an anchor, which indeed was just this side of crazy. I tried to divert the discussion to the underlying interests, but the counterpart kept insisting that I stop arguing and just make a counteroffer. I explained that I did not feel it was the time to make a counteroffer yet, so I was not going to, but if I were to consider a counteroffer it would get very close to an amount that was about 10 times more than the amount of the anchor. By dropping this amount only in a tentative manner – as a matter of speech – I introduced an expectation that served me well all during the rest of the negotiations. In a mediation, often both parties are reluctant to make the first offer. So, how can the mediator be of help? -

7 The Mediator

How can the mediator play a role in getting first offers on the table? Preferably by creating an atmosphere wherein both parties will feel safe enough to stay away from anchoring, but will be discussing their mutual interests and needs. That may include the exchange of financial data. Negotiation is then a natural process of two or more parties investigating what they can give and receive through a process of explaining and appreciating their mutual interests and needs. This, however, is not always achieved. The first rule after that is to let the parties themselves determine the moment at which they want to become serious about talking numbers. So, patience on the part of the mediator is one way to help parties come to take the step to talk about numbers in the negotiation phase.

Some parties are extremely orthodox in keeping their cards to their chests. I have mediated a case in London between parties from Israel and Germany, who succeeded in negotiating for almost 2 full days, without disclosing to one another what they had in mind as an amount for a settlement. By the end of the first long day, I was asked into the breakout room of the Israeli party. By then, it was already late at night. They proffered to let me know what the amount was that they had in mind to come to an agreement but would only do so if I promised not to tell the other side. They suggested that, knowing the amount they wanted, I go to the German party and ask them what they had in mind assuring them that I would not disclose their amount either. The idea was that knowing what both sides were aiming at, I could see whether the gap was such that it would be worthwhile to continue negotiating into the early morning or, if the gap was still substantial, we would adjourn until the next day and go to bed. During the second day, the Israeli party invited me into their breakout room and suggested that in order to move things forwards, they would allow me to tell the German party what the figure was that they had conveyed to me the night before and to tell them what the German party had said, so they could determine their position. When I went over to the other breakout room to inform the German party that I was now authorised to tell them what the figure was that the Israeli party told me last night, to my surprise they said ‘We don’t want to know.’ It was only by the end of the second day that the CEOs of both parties asked me to join them in a corner of the hallway of the law firm where the mediation took place, away from the plenary session room and the breakout rooms. They told me that they adopted one of the lessons they learned from me over the past 2 days, namely, that it was all right to agree to disagree and that they did disagree about two figures. Finally there was a ZOPA. It is up to the mediator to feel whether the time is right to move negotiations further by proposing mechanisms to enable first offers or just be patient and let the process develop itself at its own time and speed. Given the care the parties took not to show their hands earlier, it was clear in this case that patience was to be my compass in this situation.

Another way than mere patience to help the parties to start talking numbers is to suggest that both will write their number on a piece of paper and give that to the mediator. This should only occur when the parties are going around in circles without making progress. Even then, patience on the part of the mediator may still be the best strategy. Often one of the parties will towards the end begin to see that the discussions are going nowhere and finally break the spell. When the mediator becomes convinced that help is needed, the notes or closed envelopes may be mentioned as an idea to take things forwards. This approach can be suggested within a variety of options, for example, that the mediator will not disclose what is in the notes but simply indicate whether there is a (very) wide gap between the two figures or just write the figures on the flip-over and thus showing a ZOPA. The advantage being that there are two anchors at the same time and in the sense of the topic of this article, there is a level-playing field.

Another manner is shuttle diplomacy. It sometimes helps the parties that they do not have to communicate offers directly to the counterpart. They can ask the mediator to talk to the other party, suggesting what they would want to offer or receive. The mediator then serves as buffer, allowing for reactions that do not immediately invite a response from the other party, but may be discussed with the receiving party before a response is conveyed to the other side. The mediator can help a party to develop a feeling about the degree of reality of a contemplated offer or counteroffer by questioning whether there is room for manoeuvring or how one expects the other party to react to what is given to the mediator to communicate across the corridor.

A mediator can tentatively inquire whether between the brackets of two figures the parties would consider to seek a solution, seeking a ZOPA. The figures determining the brackets, however, will have to be derived from figures the parties themselves have uttered themselves at various points earlier in the mediation in order to avoid the suggestion of bias or evaluation on the part of the mediator. It is thinkable to ask both parties to mention brackets and see if there is an overlap (‘bracketing’) and thus find a ZOPA. Proposing to obtain an expert opinion as a starting point to start talking numbers is another suggestion. This may also function as a reality test or verification in case of differing standpoints about value. -

8 Conclusion

All in all, anchoring may also take place in mediation and play a role in the negotiations. It is not uncommon that a party also tries the anchoring technique on the mediator, hoping to influence the mediator in his or her communications with the other party. It is then of the essence that the mediator spots this and does not allow anchoring to cause any kind of priming or other influence on thoughts or behaviour. Perhaps this article will contribute to a greater awareness of the effects of anchoring and of possibilities to deal with that phenomenon.

-

1 See, e.g. Lempereur A. & Colson A. (2016). The First Move, A Negotiator’s Companion. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, p. 116.

-

2 Camp J. (2002). Start with No. New York: Crown Business, p. 154.

-

3 Galinsky A.D. & Mussweiler T. (2001). First Offers as Anchors: The Role of Perspective-Taking and Negotiator Focus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(4), 657-669.

-

4 Orr D. & Guthrie C. (2006). Anchoring, Information, Expertise, and Negotiation: New Insights from Meta-Analysis. Ohio State Journal on Dispute Resolution, 21, 597-629.

-

5 Among others, Chapman, G.B. & Bornstein B.H. (1996). The More You Ask For, the More You Get: Anchoring in Personal Injury Verdicts. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 10, 519, 525-528 and 532-33; and Hastie R., Schkade D.A. & Payne J.W. (1999). Juror Judgments in Civil Cases: Effects of Plaintiff’s Requests and Plaintiff’s Identity on Punitive Damage Awards. Law & Human Behavior, 23, 445 and 463-465.

-

6 See Korobkin R. & Guthrie C. (2006). Heuristics and biases at the bargaining table. In A.K. Schneider & C. Honeyman (Eds.), The Negotiator’s Fieldbook, The Desk Reference for the Experienced Negotiator. Washington: American Bar Association, Section on Dispute Resolution, pp. 351-363.

-

7 See Kahneman D. (2011). Thinking Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books, pp. 131-137.

-

8 Ross M. & Sicoly F. (1979). Egocentric Biases in Availability and Attribution. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 37(322), 324-326.

-

9 Korobkin & Guthrie (2006), pp. 292-297.

-

10 Korobkin & Guthrie (2006), pp. 52-59.

-

11 Gilovich T. & Ross L. (2016). The Wisest One in the Room, How to Harness Psychology’s Most Powerful Insights. London: Oneworld Publications, p. 84.

-

12 Schnall S. (2017). Social and Contextual Constraints on Embodied Perception. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(2), 325-340.

-

13 Id., p. 335.

-

14 Lempereur & Colson (2016), pp. 602-605.

-

15 Strack F. & Mussweiler T. (2003). Heuristic strategies for estimation under uncertainty: the enigmatic case of anchoring. In G.V. Bodenhausen & A.J. Lambert (Eds.), Foundation of Social Cognition: A Festschrift in Honor of Robert S. Wyer, Jr. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., p. 85.

-

16 Gilovich & Ross (2016), pp. 81-83.

-

17 Galinsky & Mussweiler (2001), p. 605.

-

18 Leathes M. (2017). Negotiation, Things Corporate Counsel Need to Know but Were Not Taught. Alphen aan den Rijn: Wolters Kluwer, p. 97.

-

19 Neale M.A. & Lys T.Z. (2016) Getting (More of) What You Want. London: Profile Books, chapter 7.

-

20 Northcraft G.B. & Neale M.A. (1987). Experts, Amateurs, and Real Estate: An Anchoring-and-Adjustment Perspective on Property Pricing Decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 39, pp. 84-97.

-

22 Neale & Lys (2016), p. 116.

-

23 Leathes (2017), p. 108. Neale and Lys maintain that, for example, houses sell for more when their listing prices were precise ($1,423,500) rather than round ($1,500,000) even when the round number was larger than the ‘seemingly’ precise number!

-

24 Leathes (2017), p. 109. They deservedly make a distinction for cultural differences. For example, they observed that the first offers and counteroffers that are given by carpet sellers in Istanbul are quite different from the equivalent offers and counteroffers by a carpet seller in Zurich (even when the sellers were both of Turkish origin).

DOI: 10.5553/CMJ/254246022017001002004

Corporate Mediation Journal |

|

| Article | The Negotiation Element in MediationThe Impact of Anchoring |

| Authors | Martin Brink |

| DOI | 10.5553/CMJ/254246022017001002004 |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

Suggested citation

Martin Brink, 'The Negotiation Element in Mediation', (2017) Corporate Mediation Journal 55-61

Martin Brink, 'The Negotiation Element in Mediation', (2017) Corporate Mediation Journal 55-61