-

1 Introduction

What does it mean to be a restorative university? This is different from asking how an individual at a higher education institution can respond restoratively (and not retributively) to an incident of harm and also different from asking how a university can develop a restorative justice programme that responds to student misconduct. Instead, I explore here what it might mean to create a restorative organisation, such as a university, that weaves restorative principles and practices into its normative, day-to-day environment and culture. Others have asked what it might mean to create a restorative school (Brown, 2018; González, Sattler & Buth, 2019), a restorative prison (Knoakes-Duncan, 2015; Swanson, 2009), a restorative workplace (Dekker & Breakey, 2016; Eisenberg 2015) or a restorative city (Mannozzi, 2019). Inspired, in part, by these applications, I outline some of the challenges and opportunities for restorative justice in higher education institutions (for a literature review on restorative justice in higher education, see Karp, Forthcoming). To the extent possible, I draw on applications globally but predominantly reference university campuses in the United States.

In this article I describe the emergence of contemporary restorative justice; a framework for restorative justice in higher education; implementation in student affairs; the place of restorative justice in academic affairs; restorative justice and organisational culture; what we know about campus implementation; and suggestions for practical next steps for higher education institutions to become more restorative.1.1 Universities as context for restorative justice

Universities might be seen as ‘total institutions’ (Goffman, 1961) – places where people work, study, eat and sleep and, as a result, develop particular cultural norms while also serving an instrumental role in the larger society. University cultures are typically organised around their primary educational missions: offering a liberal education that prioritises reasoned thinking and evaluation of evidence; appreciation for history and the arts; and the development of skills, be they communicative or technical (Jacoby, 2009). As a result, universities are often engines of social change by identifying and solving social problems or challenging conventional ways of knowing or behaving. Social movements often begin on university campuses, such as the Free Speech Movement, the Civil Rights Movement and the #MeToo Movement. Universities also play a role in the contemporary Restorative Justice Movement (Green, Johnstone & Lambert, 2013), with many faculty serving as early leaders (e.g. John Braithwaite at Australian National University, Gordon Bazemore at Florida Atlantic University and Howard Zehr at Eastern Mennonite University).

Within a framework of liberal education is the commitment to individual freedom of thought and experimentation. To the extent that traditionally aged students are young people often in search of their own identity and purpose (Levine & Cureton, 1998), experimentation can lead to lots of rule-breaking. In the United States, university administrators who solely manage student misconduct cases are supported by several professional associations such as the Association for Student Conduct Administration. A large university might adjudicate more than 5000 cases of misconduct per year (Rutgers University, 2023). In one study, 22 per cent of university students admitted to plagiarising articles (Hopp & Speil, 2021). Just as restorative justice may respond to crime or to K-12 (primary/secondary) school disciplinary problems, campus-based restorative justice can respond to university student misconduct.

Universities are also workplace bureaucracies with many employees and their own sets of conflicts and infractions. Sexual harassment (Young & Wiley, 2021), racial discrimination (Barber, Hayes, Johnson & Marquez-Magana, 2020) and even academic misconduct such as data fabrication (Huiskes, 2023) are common concerns. While often progressive in their liberal aspirations, universities are rigidly competitive, structured hierarchies that often lead to misuse of power. Restorative justice can be used to address these complex workplace harms. As a whole, restorative justice is not an approach that is likely to replace all other forms of remediation, especially because it is typically provided as a voluntary option for those willing to engage restoratively, i.e. non-adversarially and non-punitively. But it can offer additional productive options across higher education.1.2 Emergence of contemporary restorative justice

A restorative justice practitioner, Dennis Maloney, once quipped, ‘Restorative justice is an ancient idea whose time has come’ (Maloney, 2007), suggesting that elements of restorative principles might be found in any religion or culture, particularly within indigenous justice practices, and that it is important to acknowledge and embrace this ‘ancient idea’ that had been silenced by hegemonic Western punitive practices. Contemporary restorative justice practices are often traced to a single case in Kitchener, Ontario, in 1974, that involved a facilitated dialogue between two teenagers and a group of neighbours impacted by their vandalism (Zehr, 1990). This case led to work by the Mennonite Church to develop a framework for restorative practice. Actually, there are many contemporary origin stories, including a policing programme in Australia (Moore & McDonald, 1995), a Navajo Peacemaker Court (Yazzie, 1994), Sentencing Circles in Canada (Stuart 1996), Reparative Probation in Vermont (Karp, 2001) and many others. All of these involved criminal justice reforms and preceded restorative applications in educational institutions.

In the criminal legal system, restorative justice is a philosophical approach to crime as well as an intervention designed to be less punitive than traditional approaches, such as incarceration, and more attuned to meeting the needs of crime victims. Howard Zehr, who in 1978 developed the first restorative justice programme in the United States, defines restorative justice asan approach to achieving justice that involves, to the extent possible, those who have a stake in a specific offense or harm to collectively identify and address harms, needs and obligations in order to heal and put things as right as possible (Zehr, 2015: 48).

Taking a cue from emerging criminal justice practices in Australia, Margaret Thorsborne introduced the approach for K-12 (primary and secondary) school discipline in 1994 (Cameron & Thorsborne, 2001). Quickly, educational implementation expanded to include restorative practices aimed at prevention in addition to response to misconduct. To reflect this broader approach and to distinguish it from applications to criminal justice, educators often use the phrase ‘restorative practices’ rather than restorative justice. Morrison (2007) invoked a public health model for a ‘whole school approach’ that included three tiers of intervention: primary to prevent conflict and harm; secondary for minor interventions; and tertiary for serious incidents. This broadening of scope has led to a very different definition of restorative justice in schools than in criminal justice:

Restorative justice in education can be defined as facilitating learning communities that nurture the capacity of people to engage with one another and their environment in a manner that supports and respects the inherent dignity and worth of all (Evans & Vaandering, 2016: 8).

Given how much restorative justice has expanded beyond the criminal legal system, my own definition tries to capture both its prevention and response characteristics while retaining a central focus on harm: restorative justice is a way to prevent or respond to harm in a community with an emphasis on healing, social support and active accountability. Restorative justice includes a variety of practices, with many rooted in indigenous and religious as well as secular traditions. Some practices help prevent harm by helping people build relationships and strengthen communities. Other practices respond to harm by helping to clearly identify harms, needs and solutions through an inclusive and collaborative decision-making process.

-

2 A Framework for restorative justice in higher education

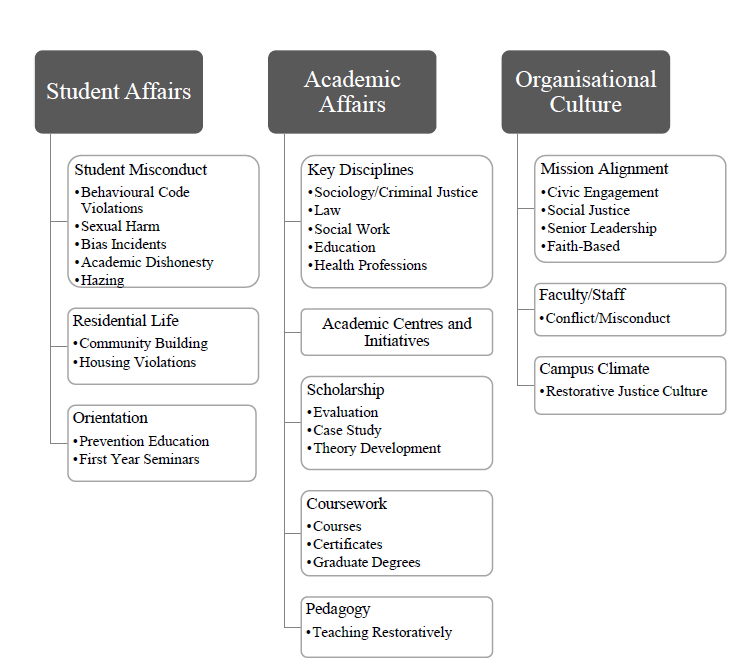

A restorative university seeks to prevent or respond to harm by using restorative practices across the institution. Rather than siloed within a singular office, such as an office of student conduct, restorative approaches are aligned with its institutional mission as a philosophical approach; apparent in the student development efforts within the division of student affairs; employed by faculty in their classrooms and as a topic of research; seen in human resources as part of their efforts to create an equitable and rewarding workplace; and facilitated by senior leadership to resolve value conflicts. Figure 1 outlines what a restorative university might do in practice to institutionalise restorative principles and practices.

2.1 Restorative justice in student affairs

Student affairs has been the epicentre of campus-based restorative justice since its introduction. Originally with a focus on student misconduct, restorative practices have expanded to address harms associated with student teams and organisations (like fraternities), as an approach to build or strengthen relationships during student orientation and in residential communities and as a way to deepen engagement and learning in prevention education, such as alcohol and drug abuse awareness or training in sexual consent.

A framework for restorative justice in higher education.

2.1.1 Student Misconduct

The first restorative justice case involving a college student that I am aware of took place in 1985 at The College of New Jersey (then called Trenton State College). The student had been arrested after a drunk driving accident, which caused the deaths of his girlfriend and roommate (T. Allena, personal communication, January 4, 2021). Thom Allena, who was working for the New Jersey court system, was aware of the case and had just read an article about restorative justice by Howard Zehr. Inspired by it, he contacted the student’s attorney and suggested a restorative approach to both the campus adjudication and the court case. Shortly thereafter, Allena met with the key stakeholders, including the parents of the deceased students, to develop a proposal that would best meet their needs. The outcome of this informal restorative justice process resulted in an outcome that the parents believed best honoured their loss, a reduced criminal sentence for the student, a substantive community service plan and the opportunity for the student to complete his education.

A decade later, Allena had moved to Colorado and become an advanced restorative justice practitioner. In 1998, the University of Colorado at Boulder hired him to train a group of student affairs staff to facilitate cases of student misconduct. Their first case, co-facilitated by Allena and Ombuds director, Tom Sebok, involved a case of vandalism and resisting arrest (Sebok & Goldblum, 1999). The programme, launched in 1999, was the first in the country, if not the world, and has grown substantially to one that maintains a close partnership with the Boulder courts and manages a caseload of more than 200 conferences per year with a volunteer facilitator pool of more than 100 (University of Colorado Restorative Justice Program, 2018).

The second campus programme was started at Skidmore College in 2000 by me when I was an assistant professor of sociology (Karp, 2004). While I was conducting research on Vermont’s Reparative Probation Programme (Karp, 2001), I was invited to review the campus disciplinary process after multiple complaints by students. We then customised the Vermont restorative approach for use on the campus. Early results were encouraging (Karp & Conrad, 2005). Thom Allena and I joined forces to capture stories of early successes at Skidmore, Boulder and other campuses, including the University of Vermont, University of California at Santa Barbara and Elizabethtown College (Karp & Allena, 2004). Subsequently, restorative justice has been used to address a wide range of student conduct violations, including alcohol and drug use (Karp & Sacks, 2013), theft/vandalism (Karp, 2011, 2019), bias incidents (Anderson, 2018; Kayali & Walters, 2019; Rico & Sullivan, 2018), academic dishonesty (Orr & Orr, 2021; Ramsey, 2004; Sopcak & Hood, 2022) and misconduct by particular student populations, such as fraternities/sororities (Allena & Rogers, 2004; McClendon, 2019) and athletes (Allena, 2004; Allena, 2017). Case studies and a review of the evidence can be found in Karp (Forthcoming) and Karp and Schachter (2018). Three campuses to date have embraced restorative justice fully enough to change the name of their student conduct offices: James Madison University Office of Student Accountability and Restorative Practices, Gallaudet University Office of Student Accountability and Restorative Practices and the University of San Diego Office of Ethical Development and Restorative Practices.

The University of Michigan Office of Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution incorporated restorative justice within a ‘spectrum of resolution options’ (Meyer Schrage, 2014) that includes conflict coaching, facilitated dialogue, mediation, restorative practices, informal and formal adjudication. That model has led to significant innovation, particularly restorative responses to student sexual misconduct (Orcutt, Petrowski, Karp & Draper, 2020).

Perhaps because traditional approaches to campus sexual harm have been so widely condemned (Gersen & Suk, 2016; Johnson, Widnall & Benya, 2018; Rice Lave, 2016; Smith & Freyd, 2014; Williamsen, 2017), restorative alternatives have received significant scholarly attention (Coker, 2016; Cyphert, 2018; Kaplan, 2017; Karp, 2019; Koss, Wilgus & Williamsen, 2014; McMahon, Williamsen, Mitchell & Kleven, 2022; Neeley, 2021; Orcutt et al., 2020). The best documented case studies of student misconduct are for sexual misconduct. On one campus in the U.S. Pacific Northwest, the approach was used to respond to a sexual assault, and the two students involved have been featured in a book chapter (Orenstein, 2020) and a podcast (Lepp, 2018).

A sexual harassment complaint at Dalhousie University in Canada received widespread media attention and controversy. A group of female dentistry students had filed a complaint against their male student peers and asked for a restorative response. However, many others in the campus community, and across Canada, were demanding expulsion, the more common punitive response. The effort to engage in a private, authentic restorative process while navigating public protest was documented by the facilitators of the restorative process and some of the students and faculty (Llewellyn, MacIsaac & MacKay, 2015; Llewellyn, Demsey & Smith, 2015; McNally, 2018). Reflections by the harmed students indicate the alignment between a restorative process and their own goals:We are Amanda and Jill and … we are two of the women from the Dalhousie Dentistry Class of 2015 … our impulse was to turn this into a matter of education, not punishment. That is not to say that we were not angry, upset, hurt, and betrayed. We were all of those things … We were given our options, very clearly, with time to think about them, as to how we would like to proceed. Luckily, there was the restorative justice option (Llewellyn, Demsey et al., 2015: 45-46).

As restorative justice becomes institutionalised, several studies have emerged that provide guidance on the structure and organisation of restorative practice (Derajtys & McDowell, 2014; Giacomini, Karp, Dixon & Glassman, 2020; Goldblum, 2009; Karp, 2009, 2019), while others have evaluated implementation and effectiveness (Gallagher Dahl, Meagher & Vander Velde, 2014; Karp & Sacks, 2014; LaCroix, 2018; McDowell, Crocker, Evett & Cornerlison, 2014; Smith, 2018). It is likely that restorative justice will continue to grow and thrive in student affairs.

What follows is a partial list of campuses that have implemented restorative practices as a response to student misconduct. The list is not exhaustive but is instead limited to those with dedicated web pages that describe how restorative justice is being utilised. The three campuses with student conduct offices dedicated to restorative justice in their titles are noted (Table 1).Table 1 Higher education institutions with dedicated restorative justice programmes in student affairs. US-based unless otherwise noted.Australian National University (Australia) Rush University Brown University Rutgers University Colorado State University Saint Mary’s College of California Dalhousie University (Canada) Stanford University Florida State University State University of New York – Buffalo Gallaudet University Office of Student Accountability and Restorative Practices The College of New Jersey George Washington University Towson University Georgia College University of Alberta (Canada) Harvard University University of California – San Diego James Madison University Office of Student Accountability and Restorative Practices University of California – Santa Cruz Liberty University University of Colorado – Boulder Loyola Marymount University University of Dayton MacEwan University (Canada) University of Denver Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of Kentucky Metropolitan State University Denver University of Michigan Michigan State University University of Pennsylvania Michigan Technical University University of Redlands New York University University of San Diego Office of Ethical Development and Restorative Practices North Dakota State University University of Texas-Austin Northwestern University University of Texas-San Antonio Oregon Coast Community College Victoria University of Wellington (New Zealand) Reed College Wilfred Laurier University (Canada) 2.1.2. Residential life

Restorative practices are increasingly used to build a positive campus community or to respond to community concerns about the campus climate. A natural home for this work is in residential life, which places an emphasis on student community building, student development and conflict resolution (Mauriello & Pierson 2018). The International Institute of Restorative Practices developed a model for building community in residence halls based on their experience at the University of Vermont (Wachtel & Miller, 2013; Wachtel & Wachtel, 2012). Whitworth (2016) evaluated this programme with a focus on how it affected leadership development of student residential advisers. Pointer (2017, 2019) describes a similar implementation at Victoria University in New Zealand. Pidgeon (2022) examined how restorative circles could ease tension between residential life and public safety departments.

2.1.3. Orientation

Restorative circles are sometimes employed for community-building purposes during student orientation. All first-year and transfer students at the University of San Diego, for example, participate in multiple circles to ease their transition to university life. In a more intensive implementation, McMahon and Karp (2020) describe a series of student-led circles in a first-year seminar. In order to deepen learning about transition topics such as alcohol abuse, sexual consent, academic integrity and cultural competence, the circles provided opportunities for authentic dialogue to augment standard prevention education workshops, which are often delivered online.

2.2. Restorative justice in academic affairs

Faculty play an important role in legitimising restorative justice in higher education. They teach the subject, develop theory and conduct research to verify its effectiveness. As a topic of inquiry, restorative justice is interdisciplinary, with interest growing across a variety of disciplines. Faculty not only teach restorative justice, they also teach restoratively, meaning they use restorative practices as a pedagogical strategy to better engage students and create more equitable learning environments. Faculty run academic centres that help support restorative justice initiatives on their own campuses as well as provide a public service to restorative justice implementation outside of the academy. Some universities have offered more than individual courses on restorative justice but opportunities for students to concentrate their studies through certificate programmes and master’s degrees. Faculty contribution to restorative justice may help legitimise its application across the university as well as in professions such as law.

2.2.1 Teaching restorative justice

Law professor Janine Geske (2005: 333-334) argues, ‘The most important benefit of teaching restorative justice in a law school is that the students develop the vision, the skills and the passion to positively transform our justice system.’ For her and other law professors, teaching about restorative justice is now a necessary part of legal education (Vedananda, 2020).

How do faculty teach about restorative justice, and where does this occur? Many faculty include restorative justice as a topic within their courses, and some offer courses with restorative justice as the focus. They appear most typically in law, criminal justice, social work and education (Armour, 2013; Britto & Reimund, 2013; Hollweck, Reimer & Bouchard, 2019; Marder & Wexler, 2021; Molloy, Keyes, Wahlert & Riquino, 2023; Vedananda, 2020). Teaching about restorative justice often includes explorations of its history and philosophy (Deckert & Wood, 2013; Carson & Bussler, 2013; Smith-Cunnien & Parilla, 2001). Many faculty provide experiential learning opportunities to ensure students can effectively learn how to facilitate restorative practices that respond to harm (Rinker & Jonason, 2014; Sweeney, 2022).

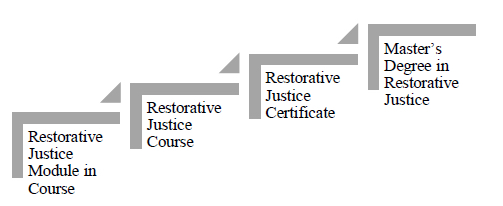

Some campuses, such as Governor’s State University and the University of San Diego, have developed concentrations, such as certificates or specialisations, and a few law schools offer restorative justice clinics, such as the University of Wisconsin and Campbell University. I am not aware of any majors in restorative justice at the undergraduate level, but there are a handful of master’s degree programmes: Eastern Mennonite University, International Institute of Restorative Practices, Vermont Law and Graduate School; in addition, we are soon launching one here at the University of San Diego. The National Centre on Restorative Justice summarised Vermont Law’s programme learning outcomes and provides a resource hub for restorative justice teaching materials (Pointer, Ojibway & Clark, 2021). Figure 2 summarises a range of current teaching applications of restorative justice.Teaching applications of restorative justice.

Table 2 lists academic programmes that, to my knowledge, offer graduate or professional coursework in restorative justice.

Table 2 Academic programmes (US-based unless otherwise noted)Master’s Degree Programmes Eastern Mennonite University Master of Arts in Restorative Justice Eastern Mennonite University Master of Arts in Education: Restorative Justice in Education International Institute of Restorative Practices Master of Science in Restorative Practices University of San Diego Master’s in Restorative Justice Facilitation and Leadership (beginning Fall 2024) Vermont Law and Graduate School Professional Certificate in Restorative Justice Certificate Programmes and Microcredentials Eastern Mennonite University Graduate Certificate in Restorative Justice Eastern Mennonite University Graduate Certificate: Restorative Justice in Education Fresno Pacific University Graduate Certificate in Restorative Justice Governors State University Graduate Certificate in Restorative Justice International Institute of Restorative Practices Graduate Certificate in Restorative Practices Maynooth University Restorative Practice Microcredential (Ireland) Oklahoma State University Certificate in Mediation and Restorative Justice Santa Clara University Graduate Certificate in Restorative Justice and Chaplaincy Simon Fraser University Professional Certificate in Restorative Justice (Canada) Suffolk University Professional Certificate in Restorative Justice Practices University of New Hampshire Professional Certificate in Mediation and Restorative Justice University of North Alabama Restorative Justice Lab Certificate in Restorative Justice (in prisons) University of North Umbria Principles and Practice of Restorative Justice Culture (England) University of San Diego Graduate Certificate in Restorative Justice Facilitation and Leadership Vermont Law and Graduate School Professional Certificate in Restorative Justice Clinical Programmes Campbell University School of Law Restorative Justice Clinic Marquette University Law School Andrew Center for Restorative Justice Northwestern University School of Law Center for Negotiation, Mediation, and Restorative Justice University of Illinois Chicago Law School Restorative Justice Project University of Kent Restorative Justice Clinic (England) University of Maryland School of Law Erin Levitas Initiative for Sexual Assault Prevention University of Wisconsin Law School Restorative Justice Project University of Saint Thomas School of Law Initiative on Restorative Justice and Healing New territory here is the systematic integration of restorative justice into professional education. For example, accreditation bodies, such as the American Bar Association or the U.S. Council on Social Work Education, do not require any education in restorative justice. Some states, such as California, require that teacher preparation programmes include some education in restorative justice: teachers should learn

principles of positive behaviour intervention and support processes, restorative justice and conflict resolution practices, and they implement these practices as appropriate to the developmental levels of students to provide a safe and caring classroom climate (Commission on Teacher Credentialing, 2016: 7).

However, in an era when academic programmes cut costs by streamlining their curriculum to essential requirements, it is unlikely that restorative justice will gain traction in professional curriculum without formal inclusion in accreditation standards.

2.2.2 Teaching restoratively

Faculty not only teach restorative justice courses but also employ restorative practices as a pedagogical approach to teaching. Some argue that teaching about restorative justice is most effective when the course is taught using restorative justice principles (Gilbert, Schiff & Cunliffe, 2013; Hollweck et al., 2019; Lyubansky, Mete, Ho, Shin & Ambreen, 2022; Marder et al., 2021; Pointer et al., 2023; Sweeney, 2022). Typically, this means incorporating circle practices to create equitable learning environments and strengthen student engagement (Bussu, Veloria & Boyes-Watson, 2018). Pointer et al. (2023) identify ‘four pillars of restorative pedagogy … (1) prioritising relationships, (2) practicing self-reflection, (3) cultivating dialogue that unearths social systems of oppression, and (4) utilising strategies for creative and experiential engagement’ (1).

2.2.3 Scholarship

Strang and Sherman (2015: 1) argue that ‘[i]n the past two decades, restorative justice has been the subject of more rigorous criminological research than perhaps any other strategy for crime prevention and victim support’. These decades have seen growth in published research across a variety of disciplines, especially law, criminology, education and social work. In a recent review, I identified over 140 peer-reviewed articles and book chapters focused on restorative justice in higher education (Karp, Forthcoming).

Because restorative justice is not housed within a singular discipline, networks of researchers and the development of cumulative research programmes have been largely informal. A new Restorative Justice Research Community (rjresearch.org) is an interdisciplinary academic community that fosters collaboration and focus for restorative justice research.2.2.4 Academic centres

With the growth in academic interest, many academic centres have been created that provide training, research and public education about restorative justice. As of this writing, I am aware of the centres provided in Table 3.

Table 3 Academic centres and initiatives. US-based unless otherwise noted.Amherst College Centre for Restorative Practices Australian National University, Centre for Restorative Justice (Australia) Bethel College Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution Bowie State University Institute for Restorative Justice and Practices Dalhousie University Restorative Research, Innovation and Education Lab (Canada) Eastern Mennonite University Zehr Institute for Restorative Justice International Institute for Restorative Practices KU Leuven Institute of Criminology Research Line in Restorative Justice and Victimology (Belgium) Loyola Marymount University Centre for Urban Resilience Restorative Justice Project Maynooth University Restorative Justice Strategies for Change (Ireland) McMaster University Centre for Human Rights and Restorative Justice (Canada) Northeastern University Law School Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project Pennsylvania State University Restorative Justice Initiative RMIT University Centre for Innovative Justice/Open Circle (Australia) Simon Fraser University Centre for Restorative Justice (Canada) Suffolk University Centre for Restorative Justice University of California-Berkeley Restorative Justice Centre University of California-Davis Transformative Justice in Education Centre University of Insubria Restorative Justice and Mediation Study Centre (Italy) University of Minnesota – Duluth Centre for Restorative Justice and Peacemaking University of Pittsburgh Centre for Race and Social Problems Justice Discipline Project University of San Diego Centre for Restorative Justice University of South Carolina Restorative Justice Initiative University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Centre for Racial and Restorative Justice Victoria University Te Ngāpara Centre for Restorative Practice (New Zealand) Walsh University Center for Restorative Justice and Community Health For a university to become fully restorative, faculty commitment is essential. They play a significant role in supporting the theory and evidence of restorative justice. They teach about it in their classrooms. And they play a vital role as members of the campus community who may build campus support for addressing harms restoratively.

2.3 Restorative justice and organisational culture

While student affairs and academic affairs neatly define major organisational structures of higher education institutions, as a whole, campuses are complex organisations that serve the needs of students, faculty, administrators, staff and the public. The campus climate is determined not only by the effectiveness of instruction but by the well-being of all members of the campus community. Broadly, a restorative university is attentive to the organisational culture, and this begins with how well the philosophy of restorative justice aligns with the mission and values of the institution. A restorative university creates an equitable, rather than toxic, workplace where faculty and staff conflict and/or misconduct is addressed restoratively.

2.3.1 Alignment between institutional mission and restorative justice

The mission of higher education is often contested, but it is generally agreed that higher education is a major location for the production of new knowledge and a place for that knowledge to be disseminated through teaching. A tension may exist, but higher education institutional missions usually speak to the instrumental (helping students to get good jobs/helping a nation remain competitive) and the inspirational (helping students become better humans/helping society become more just).

Highly instrumental institutions, like the University of Phoenix (non-residential, career-focused), aspire to both:University of Phoenix provides access to higher education opportunities that enable students to develop knowledge and skills necessary to achieve their professional goals, improve the performance of their organisations and provide leadership and service to their communities (University of Phoenix, 2023).

Highly inspirational institutions, like St. John’s College (residential, ‘great books’-focused), also aspire to both:

St. John’s College is a community dedicated to liberal education. Liberally educated persons, the college believes … are well-equipped to master the specific skills of any calling, and they possess the means and the will to become free and responsible citizens (St. John’s College, 2023).

The same broad questions may be asked of graduates of any institution: can they write a grammatically correct sentence? Can they crunch numbers using Excel? Can they improve the world around them?

To the extent that higher education remains committed to civic engagement, social justice and developing students to be moral citizens, campus communities must provide opportunities for students to learn and engage in the effort to address harm where it occurs, at both the individual and societal levels. Campus communities are often quick to observe, denounce and seek to rectify injustices. While sometimes campus outrage is directed at the institution itself, because of its educational mission, addressing such concerns is necessary for maintaining (or rebuilding) community trust, particularly among marginalised or aggrieved campus communities.

Senior leadership is largely responsible for ensuring institutions enact their mission through strategic allocation of resources and symbolic reminders about the purpose of their institutions. Strategic plans help align values and everyday activities. I mention this because a restorative university is one that sees alignment of restorative principles and institutional mission. This alignment is made transparent when the institution takes a restorative approach to building an inclusive community and to how it seeks to prevent or respond to harm when it occurs. Chris Marshall (2017: 6), in making the case for his own university – Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand – to become more restorative, argued thata restorative university, then, would be one that employs restorative practices for enhancing the relational engagement and wellbeing of its staff and student community, and restorative justice processes for dealing with incidents of misconduct and wrongdoing, whether by students or employees. Achieving this outcome would require a common commitment to and shared understanding of the goal on the part of senior leadership, student services and human resources.

Two examples illustrate instances of alignment between restorative justice and institutional mission. Leaders often make the case that their efforts are aligned with institutional mission, and sometimes these appeals follow from campus controversies and claims of institutional betrayal or harm.

In 1932, Yale University named one of its residential colleges after John C. Calhoun, Class of 1804, who served as a member of the House of Representatives, as a Senator and as Vice President of the United States (Office of the President, 2017). However, Yale changed the name of Calhoun College because of its namesake’s ties to racism and slavery. In Yale University President Peter Salovey’s announcement, he argued,the decision to change a college’s name is not one we take lightly, but John C. Calhoun’s legacy as a white supremacist and a national leader who passionately promoted slavery as a ‘positive good’ fundamentally conflicts with Yale’s mission and values (Salovey, 2017).

Similarly, the University of San Diego, where I teach, responded to controversy about one of its academic buildings because it was named after Junipero Serra, who established the first Catholic mission in California in 1769. Serra was canonised by Pope Francis in 2015. However, activists held that Serra was a coloniser and symbolises the brutal treatment of Native Americans by the Catholic Church and foreign settlers in North America. The University of San Diego is a Catholic university, so rejecting a Catholic saint by removing his name from a building was particularly fraught. In the end, the university added the name of a sainted Native American to the building, which is now referred to as Saints Tekakwitha and Serra Hall. In his announcement to the campus community, the President of the University of San Diego, James Harris, stated:

It is hoped that by placing these two Catholic saints together we will recognise that indigenous peoples preceded the Catholic missionaries who settled here … On our campus, we have been engaging in dialogue for many years about how we acknowledge the history and legay of the local indigenous tribes, and recognise that our beautiful campus is built on their homelands. We also had numerous debates and conversations about the history and legacy of Saint Junipero Serra, who was canonised by Pope Francis four years ago. The friction between these two dialogues is not easily reconciled, yet our university mission and vision require us to lean into these discussions with open minds and compassionate hearts (Payton, 2019: 1).

In both examples, university presidents explicitly refer to the missions of their institutions to ground their decisions when employing restorative responses to claims of institutional harm. For a faith-based institution, alignment is triangulated between restorative principles, religious guidance and institutional mission (Hyde, 2014; Sharpe, 2018). Seeking alignment between mission and restorative justice is a primary task for a university to become more restorative.

2.3.2 Restorative just culture

To date, much of the interest in campus-based restorative justice has been in response to student misconduct. However, a few years ago, a medical school faculty member wanted to improve the lives of medical students by restoratively addressing the way they are often mistreated by faculty and staff (Acosta & Karp, 2018; Hill et al., 2020). This shift in focus broadens the restorative justice lens from student behaviour to organisational culture. The Association of American Medical Colleges subsequently developed a project called Restorative Justice for Academic Medicine (AAMC, 2019). This effort coincided with attention towards student mistreatment across the sciences in higher education (Johnson et al., 2018) and in the healthcare profession (Carroll & Reisel, 2018). Central to this concern is the concept of a toxic workplace in which there is ‘selective accountability’ (Flores, 2022), effectively meaning that some people, such as white, male and tenured faculty, are less likely to be held accountable for abusive behaviour than others.

To approach organisational change, a restorative university may adopt an approach recently implemented in healthcare called ‘restorative just culture’ (Dekker & Breakey, 2016; Kaur, De Boer, Oates, Rafferty & Dekker, 2019). At Mersey Care, a National Health Service trust in England, three patients died by suicide in a short time while under its care. These deaths prompted significant organisational soul-searching, leading to the conclusion that Mersey Care suffered from a pervasive blame culture. This is a culture that emphasises investigation, finger-pointing and individual accountability through punishment. While the goal of blame culture, namely safety, was laudable the unintended consequence was a defensive culture in which ‘the fear of the consequences, of blame and even dismissal was the predominant staff response to an incident where harm had occurred’ (Rafferty, 2022: 34). Retooling at Mersey Care meant adopting a restorative approach with the goals of moral engagement, emotional healing, practitioner reintegration and organisational learning (Dekker, 2022: 9).

While emphasis on physical safety in higher education is not the same as it is in a healthcare organisation, harm and conflict are routine occurrences that take a toll on the campus community. One of the other lessons from Mersey Care was the recognition that minor incivilities (rudeness, belittling, dismissiveness, gossip, etc.) can accumulate to create toxic workplaces and significantly undermine productivity, collaboration and morale (Farmer, Hurst & Turner, 2022). Building a culture of restorative justice in higher education is less about disciplinary procedures and much more about creating healthy workplaces and learning environments.

Restorative justice programmes for faculty and staff have not yet emerged formally as they have with students. However, I am aware of some campuses using restorative processes to address incidents of harm. A large-scale restorative process was undertaken at the University of Rochester in response to a case of faculty misconduct. Allegations of sexual harassment led to two investigations but no findings of policy violation (Herzog, 2022; Mangan, 2018). Despite the outcomes, the campus uproar caused senior leadership to seek a restorative response that would address community concerns, particularly for the faculty member’s academic department (Ver Steeg, 2018).

To become a restorative university, campuses must expand beyond a narrow focus on student misconduct and create a new organisational culture that is supportive of all members of the campus community. -

3 Some data on implementation

Research on campus restorative justice implementation is limited (Derajtys & McDowell, 2014; LaCroix, 2018; Karp, Scharrer, Armour & Farrer, 2022; Sullivan & Witenstein, 2022). Smith (2018) evaluated the restorative justice programme at the University of Denver. Finding strong support among administrators and students, he provides the following recommendations for programme implementation and sustainability (111-118):

Establish a clear vision, as well as goals and outcomes for the restorative justice process.

Develop adequate staffing and resources to ensure long-term programme success and sustainability.

Develop ongoing mechanisms to assess and measure restorative justice and student conduct processes.

Identify ways to introduce restorative practices to students in other ways [than misconduct].

Review the language and process of restorative justice to ensure that it is inclusive and accessible.

Enhance the pre-conference preparation for students, harmed parties, and community members [the programme did not hold pre-conference meetings with harmed parties and community members].

Restructure the outcomes process, create opportunities for meaningful engagement from students and support people [he recommended that pre-conference meetings include concrete ideas for reparations].

Reconcile the University of Denver’s past, the indigenous roots of restorative justice, and appropriation of indigenous practices of talking circles and restorative justice.

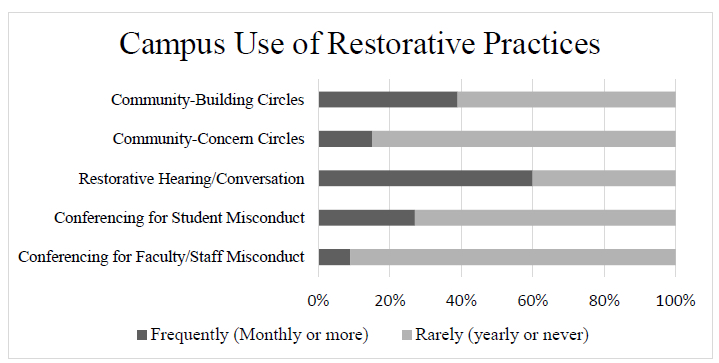

In 2019 my students and I conducted a survey of campus implementation as part of a course on research methods. Using a listserv of higher education administrators interested in or actively implementing campus restorative justice, we surveyed 315 people, representing 159 institutions (a 38 per cent response rate). It was a convenience sample, so the following statistics cannot be generalised to all higher education professionals or institutions.

Figure 3 identifies which restorative practices were most frequently implemented. Most commonly, student conduct administrators were incorporating restorative questions into conduct hearings, particularly those where administrators met one-on-one with students who violated campus policies. Also common was the use of community-building circles, such as in residential life or during orientation. Less frequent was the use of community-concern circles (that used circle practices to respond to a community concern) and restorative conferences, either for student or faculty/staff misconduct.Implementation of restorative practices

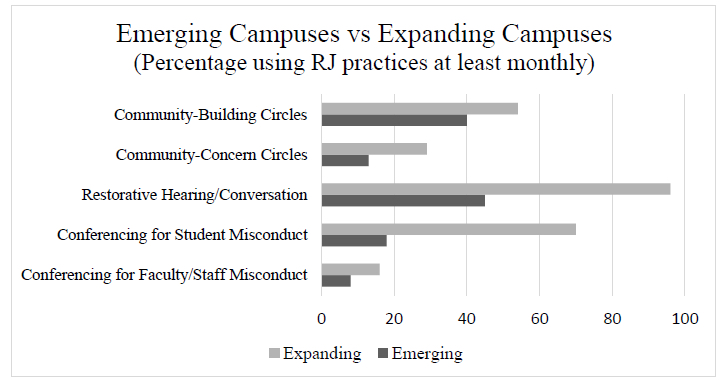

The survey also sought to identify campus implementation based on whether campus restorative justice was just ‘emerging’ or ‘expanding’ beyond initial implementation efforts. Figure 4 shows that campuses that were expanding provided restorative practices more frequently than those that were just emerging, but especially so for restorative hearings and restorative conferencing for student misconduct.

Implementation differences between emerging and expanding campuses

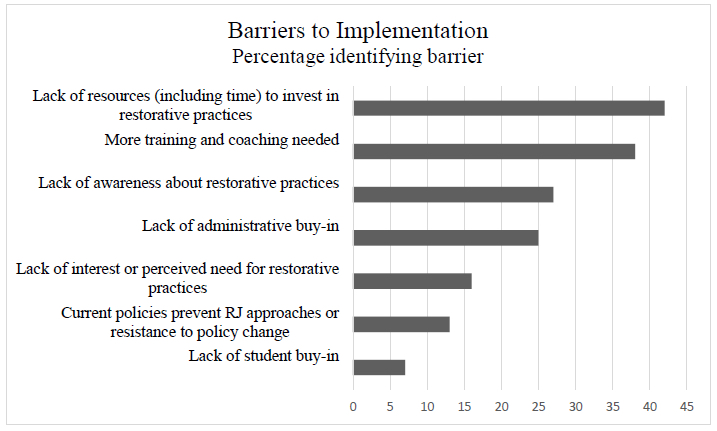

The survey also explored potential barriers to successful implementation. Figure 5 ranks barriers according to the frequency with which administrators identified them. ‘Lack of resources’ was cited most frequently. In contrast, administrators rarely identified ‘lack of student buy-in’ as an issue. In other words, students are generally very supportive of restorative justice.

Perceived barriers to implementation

-

4 Becoming a restorative university – practical steps

Becoming a restorative university is not a linear process. I once thought that changing policy was terribly important as a strategy for implementation. Embedding restorative justice into policy is indeed a milestone but not much of a guarantee. Policies are routinely reviewed and updated, and even when restorative justice becomes policy, the next year it might easily be removed. As the saying goes, ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’ (Quote Investigator, 2023): the values of the campus community must align with restorative justice for it to become institutionalised. In 2012, the student conduct office at the University of San Diego changed its name to the Office of Ethical Development and Restorative Practices. I believe this name change is more significant than changes to the student code of conduct. As a constant reminder to its staff, the name encourages them to continuously learn about and implement restorative processes.

Currently, there is no documented implementation strategy to become a restorative university. A starting place, however, might be a list of practical next steps. The National Association of Community and Restorative Justice (Karp, Scharrer, Armour & Farrer, 2022) issued a policy statement calling for higher education institutions to:Incorporate restorative justice principles into its student, faculty and staff governance policies.

Provide technical assistance and training to faculty, students and staff on the practice and implementation of restorative practices.

Encourage faculty to offer coursework in restorative justice across the liberal arts, and particularly in disciplines that prepare students for professions using restorative practices such as social work, education, higher education administration, public policy, law and criminal justice, among others.

Support research programmes in restorative justice, including basic research on the theory and causal mechanisms of restorative justice and applied research on its effectiveness.

Provide workshops for faculty on the pedagogical use of restorative practices in their classrooms.

Develop restorative justice programmes in student affairs that respond to student misconduct and threats to a positive and inclusive living and learning climate and provide opportunities for social-emotional learning, relationship-building, traumatic incidents and skills in conflict resolution and civil discourse. Areas of primary concern include student conduct, residential life, diversity and inclusion, religious and spiritual life, fraternities and sororities and athletics.

Encourage human resource departments to incorporate restorative principles and practices to improve the campus workplace for faculty and staff in their relations with one another as well as their relationships with students.

Support restorative justice through civic engagement and service learning. Provide opportunities for students to conduct independent studies, internships and community service with community-based restorative justice organisations and restorative initiatives in K-12 schools and criminal justice agencies. Encourage community-based research efforts that support restorative justice organisations. Provide policy analyses for restorative justice legislation.

I do not yet see a coherent implementation strategy, nor can I point to a fully-realised restorative university. In large part, a restorative university is always aspirational but committed to a restorative approach to relationship building and non-adversarial responses to harm and accountability. Primarily, restorative justice in higher education surfaces, often briefly, within siloed arenas, such as student conduct or residential life or a course in sociology or a research initiative. If senior leadership sees value in restorative justice or clearly identifies its alignment with their strategic goals, then institutionalisation is more likely as this level of recognition and support may help overcome the many barriers to success. Cultivating interest among various campus constituencies is a start; demonstrating effectiveness is necessary for sustained commitment. If achieved, a restorative university is one that provides both support and accountability for all of its community members, a place for learning and working that lives up to its practical and lofty educational mission.

References AAMC (2019). Restorative justice for academic medicine (RJAM): effectively responding to harm and mistreatment in the learning & workplace environments. Association of American Medical Colleges. Retrieved from https://aamc.elevate.commpartners.com/products/restorative-justice-for-academic-medicine-rjam-effectively-responding-to-harm-and-mistreatment-in-the-learning-workplace-environments-september-17-2019 (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Acosta, D. & Karp, D.R. (2018). Restorative justice as the Rx for mistreatment in academic medicine: applications to consider for learners, faculty, and staff. Academic Medicine, 93(3), 354-356. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002037.

Allena, T. (2004). Conferencing case study: applying restorative justice in a high-profile athletic incident—a guide to addressing, repairing, and healing widespread harm. In D.R. Karp & T. Allena (eds.), Restorative justice on the college campus: promoting student growth and responsibility, and reawakening the spirit of campus community (pp. 182-193). Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

Allena, T. (2017). A new paradigm for addressing athletics and sportsmanship violations: a restorative sanctioning approach. Athletics Administration, 52, 42-46.

Allena, T. & Rogers, N. (2004). Conferencing case study: hazing misconduct meets restorative justice—breaking new reparative ground in universities. In D.R. Karp & T. Allena (eds.), Restorative justice on the college campus: promoting student growth and responsibility, and reawakening the spirit of campus community (pp. 156-168). Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

Anderson, D. (2018). The use of campus based restorative justice practices to address incidents of bias: Facilitators’ experiences. University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2442.

Armour, M. (2013). Real-world assignments for restorative justice education. Contemporary Justice Review, 16(1), 115-136. doi: 10.1080/10282580.2013.769300.

Barber, P.H., Hayes, T.B., Johnson, T.L. & Marquez-Magana, L. (2020). Systemic racism in higher education. Science, 369(6510), 1440-1441. doi: 10.1126/science.abd7.

Britto, S. & Reimund, M.E. (2013). Making space for restorative justice in criminal justice and criminology curricula and courses. Contemporary Justice Review, 16(1), 150-170. doi: 10.1080/10282580.2013.769301.

Brown, M.A. (2018). Creating restorative schools. Saint Paul, MN: Living Justice Press.

Bussu, A., Veloria, C.N. & Boyes-Watson, C. (2018). StudyCircle: promoting a restorative student community. Pedagogy and the Human Sciences, 6, 1-20.

Cameron, L. & Thorsborne, M. (2001). Restorative justice and school discipline: mutually exclusive? In H. Strang & J. Braithwaite (eds.), Restorative justice and civil society (pp. 180-194). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carroll, J. & Reisel, D. (2018). Introducing restorative practice in healthcare settings. In T. Gavrielides (ed.), Routledge international handbook of restorative justice (pp. 224-232). New York: Routledge.

Carson, B.A. & Bussler, D. (2013). Teaching restorative justice to education and criminal justice majors. Contemporary Justice Review, 16(1), 137-149. doi: 10.1080/10282580.2013.769302.

Coker, D. (2016). Crime logic, campus sexual assault, and restorative justice. Texas Tech Law Review, 49, 1-64.

Commission on Teacher Credentialing (2016). California teaching performance expectations. Retrieved from www.ctc.ca.gov/educator-prep/tpa (last access 8 August, 2023).

Cyphert, A.B. (2018). The devil is in the details: Exploring restorative justice as an option for campus sexual assault responses under title IX. Denver Law Review, 96, 51-85.

Deckert, A. & Wood, W.R. (2013). Socrates in Aotearoa: teaching restorative justice in New Zealand. Contemporary Justice Review. doi: 10.1080/ 10282580.2013.769303.

Dekker, S. (2022). Introduction to restorative justice culture. In S. Dekker, A. Oates & J. Rafferty (eds.), Restorative just culture in practice: implementation and evaluation (pp. 1-20). New York: Routledge.

Dekker, S. & Breakey, H. (2016). ‘Just culture:’ Improving safety by achieving substantive, procedural and restorative justice. Safety Science, 85, 187-193. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2016.01.018.

Derajtys, K.J. & McDowell, L.A. (2014). Restorative student judicial circles: a way to strengthen traditional student judicial board practices. Journal of Theoretical & Philosophical Criminology, 6(3), 213-222.

Eisenberg, D.T. (2015). The restorative workplace: an organizational learning approach to discrimination. University of Richmond Law Review, 50, 487-556.

Evans, K.R. & Vaandering, D. (2016). The little book of restorative justice in education: fostering responsibility, healing, and hope in schools. New York: Skyhorse.

Farmer, J., Hurst, P. & Turner, C. (2022). Civility saves lives. In S. Dekker, A. Oates & J. Rafferty (Eds.), Restorative just culture in practice: Implementation and evaluation (pp. 223-250). New York: Routledge.

Flores, P.L. (2022). When “first, do no harm” fails: A restorative justice approach to workgroup harms in healthcare. (PhD Dissertation in Leadership Studies). University of San Diego. doi: 10.22371/05.2022.016.

Gallagher Dahl, M., Meagher, P. & Vander Velde, S. (2014). Motivation and outcomes for university students in a restorative justice program. Journal of Students Affairs Research and Practice, 51, 364-379. doi: 10.1515/jsarp-2014-0038.

Gersen, J. & Suk, J. (2016). The sex bureaucracy. California Law Review, 104, 881-901.

Geske, J. (2005). Why do I teach restorative justice to law students? Marquette Law Review, 89, 327-334.

Giacomini, N.G., Karp, D.R., Dixon, D.D. & Glassman, V. (2020). Off script: incorporating principles of conflict management, restorative justice, and inclusive excellence into informal and formal adjudication pathways. Chapter 12. In J.M. Schrage & N.G. Giacomini (eds.), Reframing campus conflict and student conduct practice for inclusive excellence (2nd edn., pp. 241-291). New York: Stylus.

Gilbert, M.J., Schiff, M. & Cunliffe, R.H. (2013). Teaching restorative justice: developing a restorative andragogy for face-to-face, online and hybrid course modalities. Contemporary Justice Review, 16(1), 43-69. doi: 10.1080/10282580.2013.769305.

Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums. New York: Penguin.

Goldblum, A. (2009). Restorative justice from theory to practice. Reframing campus conflict: student conduct process through a social justice lens. In J. Meyer Schrage & N.G. Giacomini (eds.), Reframing campus conflict and student conduct practice for inclusive excellence (1st edn., pp. 140-154). New York: Stylus.

González, T., Sattler, H. & Buth, A.J. (2019). New directions in whole-school restorative justice implementation. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 36(3), 207-220. doi: 10.1002/crq.21236.

Green, S., Johnstone, G. & Lambert, C. (2013). What harm, whose justice? Excavating the restorative movement. Contemporary Justice Review, 16(4), 445-460. doi: 10.1080/10282580.2013.857071.

Herzog, K. (2022). How an academic grudge turned into a #MeToo panic. Reason. Retrieved from https://reason.com/2022/03/14/how-an-academic-grudge-turned-into-a-metoo-panic/ (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Hill, K.A., Samuels, E.A., Gross, C.P., Desai, M.M., Sitkin Zelin, N., Latimore, D., Cramer, L.D., Wong, A.H. & Boatright, D. (2020). Assessment of the prevalence of medical student mistreatment by sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(5), 653-665. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0030.

Hollweck, T., Reimer, K. & Bouchard, K. (2019). A missing piece: embedding restorative justice and relational pedagogy into the teacher education classroom. The New Educator, 15(3), 246-267. doi: 10.1080/1547688X.2019.1626678.

Hopp, C. & Speil, A. (2021). How prevalent is plagiarism among college students? Anonymity preserving evidence from Austrian undergraduates. Accountability in Research, 28(3), 133-148. doi: 10.1080/08989621.2020.1804880.

Huiskes, H. (2023, July 28). Did a start researcher fabricate data in a study about dishonesty? Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/did-a-star-researcher-fabricate-data-in-a-study-about-dishonesty (last accessed 17 August, 2023).

Hyde, M. (2014). The effect of student conduct practices on student development in Christian higher education. (PhD Dissertation). Liberty University. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/865 (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Jacoby, B. (ed.). (2009). Civic engagement in higher education: concepts and practices. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Johnson, P.A., Widnall, S.E. & Benya, F.F. (eds.). (2018). Sexual harassment of women: climate, culture, and consequences in academic sciences, engineering, and medicine. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24994.

Kaplan, M. (2017). Restorative justice and campus sexual misconduct. Temple Law Review, 89, 701.

Karp, D.R. (2001). Harm and repair: observing restorative justice in Vermont. Justice Quarterly, 18, 727-757.

Karp, D.R. (2004). Integrity boards. In D.R. Karp & T. Allena (eds.), Restorative justice on the college campus: promoting student growth and responsibility, and reawakening the spirit of campus community (pp. 29-41). Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

Karp, D.R. (2009). Reading the scripts: the restorative justice conference and the student conduct hearing board. In J.M. Schrage & N.G. Giacomini (eds.), Reframing campus conflict and student conduct practice for inclusive excellence (1st edn., pp. 155-174). New York: Stylus.

Karp, D.R. (2011). Spirit horse and the principles of restorative justice. Student affairs eNews. December 20.

Karp, D.R. (2019). A restorative justice approach to campus sexual misconduct. In S. Coontz, P. England & V. Rutter (eds.), Council on contemporary families symposium: defining consent. Retrieved from www.contemporaryfamilies.org (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Karp, D.R. (2019). Restorative justice and responsive regulation in higher education: the complex web of campus sexual assault policy in the United States and a restorative alternative. In G. Burford, V. Braithwaite & J. Braithwaite (eds.), Restorative and Responsive Human Services (pp. 143-164). New York: Routledge.

Karp, D.R. (Forthcoming). Restorative justice in higher education: a literature review. In K.R. Roth, F. Kumah-Abiwu & Z.S. Ritter (eds.), Handbook of restorative justice and practice in U.S. higher education. London: Palgrave.

Karp, D.R. & Allena, T. (eds.). (2004). Restorative justice on the college campus: promoting student growth and responsibility, and reawakening the spirit of campus community. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

Karp, D.R. & Conrad, S. (2005). Restorative justice and college student misconduct. Public Organization Review, 5, 315-333.

Karp, D.R. & Sacks, C. (2013). Research findings on restorative justice and alcohol violations. NASPA knowledge community publication. Fall (pp.11-17). Retrieved from https://naspa.org/images/uploads/kcs/Spring-2013-KC-Publication-FINAL-032713.pdf (last accessed 17 August, 2023).

Karp, D.R. & Sacks, C. (2014). Student conduct, restorative justice, and student development: findings from the student accountability and restorative research project. Contemporary Justice Review, 17, 154-172.

Karp, D.R. & Schachter, M. (2018). Restorative justice in colleges and universities: what works when addressing student misconduct. In T. Gavrielides (ed.), The Routledge handbook of restorative justice (pp. 247-63). New York: Routledge.

Karp, D.R., Scharrer, J., Armour, M., & Farrar, H. 2022. NACRJ higher education restorative justice policy statement and implementation and management guidelines. National Association of Community and Restorative Justice. Retrieved from https://www.nacrj.org/policy-and-position-statements/ (last access 8 August, 2023).

Kaur, M., De Boer, R.J., Oates, A., Rafferty, J. & Dekker, S.W.A. (2019). Restorative just culture: A study of the practical and economic effects of implementing restorative justice in an NHS Trust. MATEC Web of Conferences, 273, 9. doi: 10.1051/matecconf/201927301007?

Kayali, L. & Walters, M. (2019). Prejudice and hate on university campuses: repairing harm through student-led dialogues. Sussex, England: University of Sussex. Retrieved from https://www.sussex.ac.uk/webteam/gateway/file.php?name=final-evaluation-report-prejudice-and-hate-on-university-campuses---repairing-harms-through-student-led-restorative-dialogue.pdf&site=67 (last accessed 17 August, 2023).

Knoakes-Duncan, T. (2015). Restorative justice in prisons: A literature review. Occasional Papers in Restorative Justice Practice, 4. Victoria University of Wellington.

Koss, M.P., Wilgus, J.K. & Williamsen, K.M. (2014). Campus sexual misconduct: Restorative justice approaches to enhance compliance with title IX guidance. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 15, 242-257. doi: 10.1177/1524838014521500.

Lepp, S. (2018). A survivor and her perpetrator find justice. Reckonings [Audio podcast]. www.reckonings.show/episodes/21 (last accessed 17 August, 2023).

LaCroix, L.L. (2018). Restorative justice in higher education: a case study of program implementation and sustainability (PhD Dissertation). University of California, San Diego. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/78972339 (last access 8 August, 2023).

Levine, A. & Cureton, J.S. (1998). When hope and fear collide: a portrait of today’s college students. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass.

Llewellyn, J.J., Demsey, A. & Smith, J. (2015). An unfamiliar justice story: restorative justice and education. Reflections on Dalhousie’s Facebook incident 2015. Our Schools/Our Selves, 25, 43-56.

Llewellyn, J.J., MacIsaac, J. & Mackay, M. (2015). Report from the restorative justice process at the Dalhousie university faculty of dentistry. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada: Dalhousie University.

Lyubansky, M., Mete, G., Ho, G., Shin, E. & Ambreen, Y. (2022). Developing a more restorative pedagogy: aligning restorative justice teaching with restorative justice principles. In G. Valez & T. Gavrielides (eds.), Restorative justice: promoting peace and wellbeing (pp. 79-106). New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-13101-1_5.

Maloney, D. (2007). A sense of justice [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/Y7MhQG5BiYQ (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Mangan, K. (2018). Rochester professor at centre of harassment controversy will return to teaching. Chronicle of Higher Education. April 5.

Mannozzi, G. (2019). The emergence of the idea of restorative city and its link to restorative justice. International Journal of Restorative Justice, 2(2), 288-292. doi: 10.5553/IJRJ/258908912019002002006.

Mauriello, L. & Pierson, M.C.S. (2018). Facilitating conflict resolution. In J. Hudson, A. Acosta & R.C. Holmes (eds.), Conduct and community: a residence life practitioner’s guide (pp. 217-251). College Station, TX: Association for Student Conduct Administration.

Marder, I.D., Vaugh, T., Kenny, C., Dempsey, S., Savage, S., Weiner, R., Duffy, K. & Hughes, G. (2021). Enabling student participation in course review and redesign: Piloting restorative practices and design thinking in an undergraduate criminology programme. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 33(4), 526-547. doi: 10.1080/10511253.2021.2010781.

Marder, I.D. & Wexler, D.B. (2021). Mainstreaming restorative justice and therapeutic jurisprudence through higher education. University of Baltimore Law Review, 50(3), 399-423.

Marshall, C. (2017). Victoria University of Wellington: Towards a restorative university? Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University.

McClendon, R.S. (2019). Professionals’ perspectives on a restorative justice approach to fraternity and sorority misconduct in higher education. (PhD Dissertation). Shenendoah University. Retrieved from www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/professionals-perspectives-on-restorative-justice/docview/2323168849/se-2 (last accessed 8 August 2023).

McDowell, L.A., Crocker, V.L., Evett, E.L. & Cornerlison, D.G. (2014). Perceptions of restorative justice concepts: An evaluation of university housing residents. Contemporary Justice Review, 17, 346-361. doi:10.1080/10282580.2014.944799.

McMahon, S.M. & Karp, D.R. (2020). Building relational and critical thinking skills: The power of peer-led RJ circles among first year college students. Chapter 10. In J.M. Schrage & N.G. Giacomini (Eds.), Reframing campus conflict and student conduct practice for inclusive excellence (2nd edn., pp. 308-321). New York: Stylus.

McMahon, S.M., Williamsen, K.M., Mitchell, H.B. & Kleven, A. (2022). Initial reports from early adopters of restorative justice for reported cases of campus sexual misconduct: a qualitative study. Violence Against Women, 29(6-7). doi: 10.1177/10778012221108419.

McNally, M.E. (2018). A restorative approach to professional responsibility: lessons from the 2014-2015 Dalhousie faculty of dentistry Facebook incident. The International Journal of Restorative Justice, 1, 438-444. doi:10.5553/IJRJ/258908912018001003009.

Meyer Schrage, J. (2014). A sea change on the horizon: Transforming our students and campuses through innovative conflict management. About Campus, 19(3), 17-25. doi: 10.1002/abc.21158.

Molloy, J.K., Keyes, T.S., Wahlert, H. & Riquino, M.R. (2023). An exploratory integrative review of restorative justice and social work: Untapped potential for pursuing social justice. Journal of Social Work Education, 59(1), 133-148. doi: 10.1080/10437797.2021.1997690.

Moore, D. & McDonald, J. (1995). Achieving the ‘good community’: a local police initiative and its wider ramifications. In K.M. Hazlehurst (ed.), Perceptions of justice. Issues in indigenous and community empowerment (pp. 143-173). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Morrison, B. (2007). Restoring safe school communities: a whole school response to bullying, violence and alienation. Alexandria, Australia: Federation Press.

NACRJ (2019). NACRJ policy statement on community and restorative justice in higher education. National Association of Community and Restorative Justice.

Neeley, J. (2021). Addressing sexual assault in criminal justice, higher education and employment: what restorative justice means for survivors and community accountability. The Kansas Journal of Law and Public Policy, 31(1), 1-60. Retrieved from https://lawjournal.ku.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/3_Neeley_Final_v31_I1-2.pdf (last accessed 17 August, 2023).

Office of the President (2017). Decision on the name of Calhoun College. Yale University. Retrieved from https://president.yale.edu/decision-name-calhoun-college (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Orcutt, M., Petrowski, P.M., Karp, D.R. & Draper, J. (2020). Restorative justice approaches to the informal resolution of student sexual misconduct. Journal of College and University Law, 45(2). Retrieved from https://www.nacua.org/resource-library/resources-by-type/journal-of-college-university-law/index-by-volume/jcul-by-volume-landing-page/volume-45-number-2 (last accessed 17 August, 2023).

Orenstein, P. (2020). Boys and Sex. New York: HarperCollins.

Orr, J.E. & Orr, K. (2021). Restoring honor and integrity through integrating restorative practices in academic integrity with student leaders. Journal of Academic Ethics, 21(1), 55-70. doi: 10.1007/s10805-021-09437-x.

Payton, P.G. (2019). USD approves name changes for four campus spaces. University of San Diego news center. Retrieved from www.sandiego.edu/news/detail.php?_focus=71799 (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Pidgeon, S. (2022). Public safety presence and response in campus housing: Using restorative justice interventions to mitigate harm and restore trust in the residential community. M.A. in Higher Education Leadership: Action Research Projects. Retrieved from https://digital.sandiego.edu/soles-mahel-action/96 (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Pointer, L. (2017). Building a restorative university. The Australian and New Zealand Student Services Association, 25(2), 63-70. doi: 10.30688/janzssa.2017.17.

Pointer, L. (2019). Restorative practices in residence halls at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 36(3), 263-271. doi: 10.1002/crq.21240.

Pointer, L., Dutreuil, C., Livelli, B., Londono, C., Pledl, C., Rodriguez, P., Showalter, P. & Tompkins, R.P. (2023). Teaching restorative justice. Contemporary Justice Review, doi: 10.1080/10282580.2023.2181286.

Pointer, L., Ojibway, A. & Clark, S. (2021). Vermont law school master of arts in restorative justice curriculum mapping and evaluation process report. National Center on Restorative Justice. Retrieved from https://ncorj.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Curriculum-Mapping-Process-Report.pdf (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Quote Investigator (2023). Culture eats strategy for breakfast. Retrieved from https://quoteinvestigator.com/2017/05/23/culture-eats/ (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Rafferty, J. (2022). Creating a restorative justice culture in a large public organization: A personal reflection from Mersey Care’s chief executive. In S. Dekker, A. Oates & J. Rafferty (eds.), Restorative just culture in practice: implementation and evaluation (pp. 21-46). New York: Routledge.

Ramsey, J. (2004). Integrity board case study: Sonia’s plagiarism. In D.R. Karp & T. Allena (eds.), Restorative justice on the college campus: promoting student growth and responsibility, and reawakening the spirit of campus community (pp. 136-141). Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

Rice Lave, T. (2016). Ready, fire, aim: How universities are failing the constitution in sexual assault cases. Arizona State Law Journal, 48, 637.

Rico, R. & Sullivan, K. (2018). Texas fraternity bias incident: a restorative justice case study. San Diego: University of San Diego Center for Restorative Justice.

Rinker, J.A. & Jonason, C. (2014). Restorative justice as reflective practice and applied pedagogy on college campuses. Journal of Peace Education, 11, 162-180.

Rutgers, University. (2023). Student conduct & academic integrity statistics: AY 2022-23 end-of-year data. Office of Student Conduct. Retrieved from https://studentconduct.rutgers.edu/about-us/student-conduct-academic-integrity-statistics (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Salovey, P. (2017). Decision on the name of Calhoun College. Yale University. Retrieved from https://president.yale.edu/president/statements/decision-name-calhoun-college (last accessed 8 August 2023)

Sebok, T. & Goldblum, A. (1999). Establishing a campus restorative justice program. California Caucus of College and University Ombuds, 2, 12-22.

Sharpe, S. (2018). Restorative justice and Catholic Social Tradition: a natural alignment. Restorative Justice Network of Catholic Campuses. University of San Diego Center for Restorative Justice. March.

Smith, C.P. & Freyd, J.J. (2014). Institutional betrayal. American Psychologist, 69(6), 575-587. doi: 10.1037/a0037564.

Smith, R. (2018). Fostering accountability and repairing harm: a program evaluation of restorative justice at the University of Denver. (PhD Dissertation). University of Denver. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.du.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1012&context=he_doctoral (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Smith-Cunnien, S.L. & Parilla, P.F. (2001). Restorative justice in the criminal justice curriculum. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 12(2), 385-403. doi: 10.1080/10511250100086191.

Sopcak, P. & Hood, K. (2022). Building a culture of restorative practice and restorative responses to academic misconduct. In S.E. Eaton & J. Christensen Hughes (eds.), Academic Integrity in Canada (Vol. 1, pp. 553-571). New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-83255-1_29.

St. John’s College (2023, February 23). Statement of the program. Retrieved from www.sjc.edu/academic-programs/statement-of-the-program#:~:text=Introduction-,St.,the%20search%20for%20unifying%20ideas (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Strang, H. & Sherman, L. (2015). The morality of evidence. Restorative Justice: An International Journal, 3, 6-27. doi: 10.1080/20504721.2015.1049869.

Stuart, B. (1996). Circle sentencing in Yukon Territory, Canada: a partnership of the community and the criminal justice system. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 20, 291-309.

Sullivan, M. & Witenstein, M.A. (2022). Infusing restorative justice practices into college student conduct practices. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 15(6), 695-699. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000445.

Swanson, C. (2009). Restorative justice in a prison community. Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Lexington.

Sweeney, R. (2022). Restorative pedagogy in the university criminology classroom: learning about restorative justice with restorative practices and values. Laws, 11(4), 58-69. doi: 10.3390/laws11040058.

University of Colorado Restorative Justice Program. (2018). CURJ annual report 2017/18. University of Colorado.

University of Phoenix. (2023, February 23). Mission and purpose. Retrieved from www.phoenix.edu/about/mission-purpose.html (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Vedananda, N.S. (2020). Learning to heal: integrating restorative justice into legal education. New York Law School Law Review, 64, 96-113.

Ver Steeg, J. (2018). Rochester implements restorative practices. University of Rochester News Center. Retrieved from www.rochester.edu/newscenter/rochester-implements-restorative-practices-336762/ (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Wachtel, T. & Miller, S. (2013). Creating healthy residential communities in higher education through the use of restorative practices. In K.S. van Wormer & L. Walker (eds.), Restorative justice today: practical applications, (pp. 92-99). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wachtel, J. & Wachtel, T. (2012). Building campus community: restorative practices in residential life. Bethlehem, PA: IIRP.

Whitworth, P. (2016). Powerful peers: resident advisors’ experience with restorative practices in college residence hall settings (PhD Dissertation). University of Vermont. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/491 (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Williamsen, K.M. (2017). ‘The exact opposite of what they need.’ Administrator reflections on sexual misconduct, the limitations of the student conduct response, and the possibilities of restorative justice (PhD Dissertation). University of Minnesota. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/11299/190564 (last accessed 8 August 2023).

Yazzie, R. (1994). Life comes from it: Navajo justice concepts. New Mexico Law Review, 24, 175-190.

Young, S. & Wiley, K. (2021). Erased: ending faculty sexual misconduct in academia an open letter from women of public affairs education. Public Policy and Administration, 37(3), 255-260. doi: 10.1177/09520767211015408.

Zehr, H. (1990). Changing lenses: a new focus for crime and justice. Harrisonburg, VA: Herald.

Zehr, H. (2015). The little book of restorative justice. New York: Skyhorse.

The International Journal of Restorative Justice |

|

| Article | Becoming a restorative university: The role of restorative justice in higher education |

| Keywords | restorative practices, higher education, tertiary education, university, restorative justice |

| Authors | David Karp |

| DOI | 10.5553/TIJRJ.000175 |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Abstract Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

David Karp, 'Becoming a restorative university: The role of restorative justice in higher education', (2024) The International Journal of Restorative Justice 304-331

|

This article describes the concept of a restorative university, an organisation that embraces restorative justice principles and practices. The article reviews the emergence of contemporary restorative justice; a framework for restorative justice in higher education; implementation in student affairs; the place of restorative justice in academic affairs; restorative justice and organisational culture; what we know about campus implementation, including results of a survey of universities; and suggestions for practical next steps for higher education institutions to become more restorative. Wherever possible, the article references restorative applications globally but predominantly focuses on university campuses in the United States. |