-

1. Re-enacting mediation in Inside the distance

Dzur: How did you get interested in restorative justice? What brought you into that world of thinking?

Daniel: I’d been working for a number of years on projects that were extremely critical of the criminal legal system in the US, and I was interested in trying to find productive alternatives to our punitive retributive justice system. I happened to be in Belgium because I was invited to exhibit one of my projects in the STUK Artefact festival. STUK is a multifaceted arts organisation. They very generously brought me to the festival and asked me to do a talk for a group of researchers from a legal institute at KU Leuven.

The curators who organised the talk had in mind all along that I would want to meet these people and that they might want to meet me and that we might do something together. So after the talk we had drinks at the bar, and we got into a big conversation, and I started to learn more about the research that these specific faculty and PhD students were doing in restorative justice.

Pieter-Paul Mortier, the curator, watched this conversation going on and said, ‘Well, there might be some funding available for you to do work together’. And we all thought that was a great idea. We did get the funding, which was a special kind of arts research funding in Belgium specifically targeting projects between arts researchers and non-arts researchers.

They gave us two years of funding. Compared to the kind of funding they would normally get for research at KU Leuven it was a very small grant but compared to arts funding in the USA, it was pretty substantial. It allowed me to travel back and forth several times over a two-year period to interview and have conversations with people in the restorative justice field there and people who had been involved in victim-offender mediation.

After doing a series of interviews with scholars, faculty and PhD students who were doing research in the field, I decided that I wanted to interview the mediators and practitioners who were actually engaged in mediations, specifically in cases of serious, violent crimes. So I did a bunch of interviews with mediators. I was also able to do a few interviews with victims and offenders who had participated in mediations in serious cases. I decided, after learning more about the practice of restorative justice, specifically in Belgium, that the project should help educate people about the availability, usefulness and power of these sorts of mediation practices in the context of really serious cases.Dzur: This is the germ of your Inside the distance project.

Daniel: Yes.

Dzur: Could you briefly describe this project for readers who might be unfamiliar with it? What kinds of stories do people encounter when they view Inside the distance?

Daniel: In my conversations with mediators, they told me stories of really interesting cases of mediation.

One of the stories that I heard early on, from Kristel Buntinx, was about a mediation where a rape victim, after many years, decided that she wanted to meet the person who had assaulted her. She contacted the mediation service. At first, they did shuttle mediation, and then they scheduled face-to-face mediation with the person who had assaulted her who was still incarcerated.

When they were planning this face-to-face mediation, Kristel told the victim that they would be meeting in a legal visiting room, and the victim imagined that would be a large room with a big table. On the day itself, however, she entered the room and discovered it was a small room and could see immediately the close physical proximity she was going to have with the person who had sexually assaulted her. She lost her nerve and didn’t want to go through with it because she didn’t want to be so close to the offender.

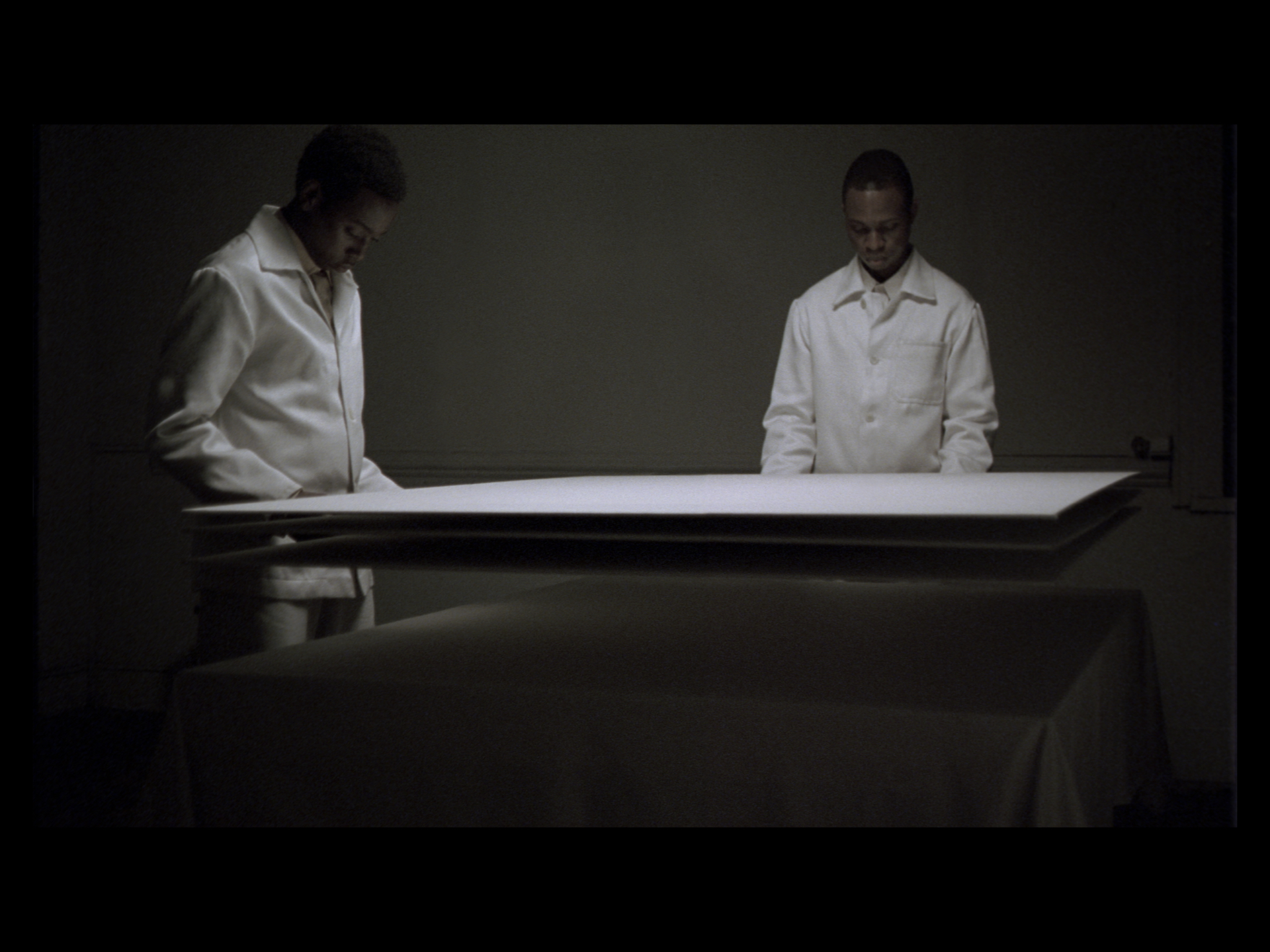

Kristel took her out; they found a different table and got a different situation. They brought her back, and they were able to have the mediation. That was the first story where I started to think about the significance of the table as a space of mediation.Dzur: In Inside the distance, the table is represented by a very stark white board. Can you say more about why the table was intriguing to you and worth further exploration?

Daniel: There were several different stark white boards that got set on these trestle legs, to make different size tables for different scenes of mediation that are represented in the piece.

Inside the Distance.

The piece is based on interviews in which people describe the story of the mediation taking place. I had those stories from the perspectives of the mediators, but also a few from the perspective of the victim and from the perspective of the offender. I wanted to put together an interface that didn’t homogenise them but that brought them all into a particular kind of theatrical space so they could, in a way, be enacted.

Most of the interviews I recorded were basically talking heads, and some were just audio. I had to create a visual context to represent this material in an interface. I also had a lot of interview material in different languages; some of the interviewees were more comfortable speaking in Dutch or in French. One of the offenders was unable to have his own voice in a media project or on the news because he had made an agreement with his victim’s family. In the cases of the non-English interviews and in the case of that particular offender, I had to record actors reading the texts of the interviews that I wanted to use in the project. That was one of the reasons I started thinking about using this kind of abstract theatrical space as a set in which to render these different stories. I wanted each scene or story to focus on what happened within the space of the mediation, sitting at the table, where the victim and offender encounter each other or where the mediator has a conversation with either victim or offender.

Most of the stories of mediation I heard from mediators or victims or offenders began with a kind of rehearsal of what happened when the crime was actually committed – you did that, and then I did this. Coming to an agreement on a version of what happened came before getting into the questions of why, and why me, and what did you think of me at that moment?

I thought of that in terms of re-enactment and decided I could use re-enactment, not of the crime but of the encounter between victim and offender in the space of mediation to examine the dynamic of what happens and all the questions that arise, such as why, why me and what did you think of me? I was trying to use that to get at the premise, which is the tagline of the project: we are all victims, we are all offenders.

The lighting and the visual texture were influenced by a painting that I saw by a Belgian painter. In this painting, what looks like two prisoners or maybe two healthcare workers are sitting in this very gloomy dark space with a very brightly lit table in front of them. I was already thinking about the table as the kind of symbolic space of mediation and how it operated to open and close the distance between the victim and the offender based on that story that Kristel told me. And that is also how the title emerged, alluding to what can happen inside that space of distance in the context of mediation.Michaël Borremans. The Feeding, 2006. LCD monitor in wooden frame; 35mm film transferred to DVD, 4:50 min (loop), color, silent. Screen: 19 x 35 inches. 48.3 x 88.9 cm. © Michaël Borremans. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner.

I created all the visuals during a four-day video shoot in a big black box room we have at my university. I hired some actors and also had some students helping. We shot these silent tableau-like enactments where, in some cases, I would read the interview to the people doing the enactment while we were doing the enactment, and, in some cases, I read it to them beforehand and then gave them instructions. We had a four-camera set-up in the space to capture multiple perspectives, and we shot numerous takes of each ‘enactment’. I edited the footage related to each story to the audio of the interview in which the mediation in question was described by the mediator or one of the participants.

The project has three major sections – ‘the accounts’, ‘the positions’ and ‘the spaces’. After the introduction the viewer lands in ‘the accounts’, which contains stories of mediation as told by mediators. In ‘the positions’ section the screen is split between victim, mediator and offender. You can choose one or another area of the screen, and that opens up and activates a video where you are hearing the perspective of a mediator or a victim or offender in reference to one or another of the cases documented in ‘the accounts’ section. In ‘the spaces’ section, practitioners talking about their theories of mediation, or the type of practice and the thinking behind their practice, and also about how they apply that to specific cases. It’s less narrative and more theoretical or philosophical, with statements by people such as Leo Van Garsse, Bram Van Droogenbroeck and Kristel Buntinx. -

2. The challenge and promise of mediation

Dzur: It is not always sunshine and happy endings in Inside the distance. A few victims would come in angry, and they would leave angry, though the fact that they were able to distribute their anger across the table was productive. One mediator talks about how just one hour of mediation was exhausting for everyone, particularly the offender, dispelling the idea that mediation is the easy way out. Was the hard work, the physically and emotionally draining nature of mediation, something you had anticipated going into this project?

Daniel: No, I didn’t really know very much about the mediation process when I started. I believed that it was a great alternative approach, but I wanted to research and document the use of mediation in serious cases because I felt like that’s where the question is. That’s where the public might doubt whether this process is useful or safe or helpful for the victim or offender or whether it is just an easy way out for the offender who might do it just to score some points for probation.

I learnt so much from the mediators, who thoroughly prepared me for talking to the victims and offenders by telling me their stories and talking about their own experiences. I learnt from the mediators, victims and offenders that participating in mediation is really challenging and difficult emotionally and psychologically. It was interesting and surprising to hear the offenders express their concern for how the victims saw them, both at the moment that the crime occurred and in the mediation, in this moment of contact with this person that they had harmed or with the family of the person they had harmed.Dzur: One question that comes up with respect to serious cases is about continuing a forced relationship. The premise of mediation, as related in Inside the distance, is that we are all victims and we are all offenders. But, in fact, we’re not all offenders with respect to this particular person who’s across the table from us, and we’re not all offenders, or victims, in the same ways. The serious offence is one that might have forced a kind of relationship that is painful to reproduce and extend. I wonder if your experience with re-enacting mediation offers any insight on why it’s good to continue a relationship one never wanted.

Daniel: That’s an interesting question. I hadn’t thought of mediation necessarily in terms of continuing the relationship. I didn’t get to speak to as many victims or offenders as I hoped to. But I did find, in these cases, that most victims were hoping to understand, resolve and close that relationship rather than continue it.

Your question makes me think of one of the cases in the project in which a young woman was sexually assaulted at knifepoint. At first, she was reluctant to do an interview, and I didn’t get to meet with her but, eventually, she agreed to an interview with Bie Vanseveren, the mediator she had worked with. They spoke in Dutch so had to be translated and voiced over.

We agreed that she could see how her case was represented in the project before allowing it to be included. I had to do all the editing of everything about her case and send it to her to get her approval before the launch and exhibition. This was a lot of work, given the possibility that this story which is represented in all three sections of the piece might not make it in.

But, in the end, she was happy with it, so it was included, and then she came and brought her family to the exhibition at STUK when we premiered the project. I gave them a tour of the whole exhibition, which was much larger than just Inside the distance. We had coffee and spent almost a whole day together. We invited her to a panel that was taking place a few days later that was part of the programming related to the exhibition. She was interested but also very nervous about coming, and she said, ‘I don’t want anyone to know that I’m part of this’. And I said, ‘No one’s going to know it is you, and you don’t have to say anything if you don’t want to.’ And so she came to this panel, and she identified herself and spoke about how mediation had helped her. After that, she decided to advocate for restorative justice. It was transformative for her in a really interesting way.

I think mediation had helped her get closure because during the face-to-face meeting she’d come to understand the pathology of the person who had assaulted her was based in his own background of sexual abuse. Then she started to feel like she could speak more publicly about her experience after having participated in the project and seeing her own experience reflected back to her in a positive way. -

3. Art and restorative justice: gathering many voices for political conversation

Dzur: That’s an interesting example of how art can connect to issues in a really embodied way. And this raises the general question of how art relates to justice work and the more specific question of how your work connects up with the restorative justice movement. It does not seem like you intend the artwork to have a particular effect on particular people, nor be something that’s simply a useful tool for restorative justice practitioners and advocates. Nevertheless, there are these relationships and transformative moments that occur, as with this former victim.

Daniel: I don’t ever really imagine a work having a specific effect on a specific person. But I did want this project to be a tool for restorative justice research and practice. That was actually an explicit goal of the collaboration, and I believe it’s being used in that way, at least in the Belgian context. I’ve heard from a couple of people in the US, too, who use it in teaching about mediation. That is very gratifying for me because I want it to have a role of enacting something and persuading people to question their assumptions about how criminal legal systems work.

Dzur: At the same time, this is not exactly a standard pedagogical tool. What you’re doing is quite a bit different than a ‘how to’ video.

Daniel: Absolutely true. I don’t think of it in terms of a study guide or anything like that. I have a very specific way that I work both in terms of the structure and the design of a project that I consider to be a work of art.

Dzur: ‘Tool’ means what, then, in this context of the work of art?

Daniel: I think that art can have impact: it can be persuasive, it can create public records of events. Now, I work based on real things, things that real people say and have experienced.

I have an aesthetic, but I’m not as interested in questions of aesthetics like ‘what is beauty, as I am in questions of ethics like ‘how should we live’ and in questions of practical effects, as in ‘what can art do?’ Those are questions, in some cases, of politics, or systemic analysis.

For me, the role of art, and my work specifically, is to bring forward a kind of political speech that can help to foster new political subjects, to humanise incarcerated people, to cause the public to question their assumptions and perceptions about justice in the criminal legal system.

I work in a particular way, which I think of in terms of polyphony or multivocality. I think it takes more than a single story about one person’s experience to address structural injustices like racism and mass incarceration. So for each documentary project I gather as many different voices, perspectives and specific experiences as I can from the individuals and communities I work with in the hope that the project will bring the very particular and individual experiences of each participant together as a kind of collective statement or record.

I think of the social problem like mass incarceration as a 100-square-mile site that I populate, like a database, with the stories and statements of impacted communities. I design an interface to that database that sets the viewer down somewhere within that site. They have to find their own way through it and encounter what they encounter by the choices they make. I almost always use quotes from the statements that my interviewees have made as the interface elements that the viewer has to choose from, so that the interface itself expresses the views of the participants and the viewer is able to follow a trajectory based on their own interest or what they find compelling.Dzur: What you’ve been describing could be put crudely as a sort of three-dimensional ethnography in time. But your artwork is ultimately quite different than ethnography. I’m thinking of Beverly Henry in Undoing time, telling her story draped in an American flag that was made in the correctional institution for 65 cents an hour. And here she is, stitch by stitch, and stripe by stripe, undoing this flag. That’s more than ethnography, and it carries significant symbolism. You don’t use the word beauty to describe your goals, but I found her beautiful and the whole scene beautiful. How do you find somebody like Beverly Henry, and how choreographed was that scene?

Daniel: That was fairly choreographed. I met Beverly when I was working on Public secrets. She was the first incarcerated woman I spoke with on my first visit to a state prison. I interviewed her many times while she was still incarcerated at the Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF). She became a kind of a muse for me. She was so articulate, and her way of speaking was so powerful. She was a peer organiser inside the prison and introduced me to other women that I also interviewed for Public secrets.

We stayed in touch when she finally was paroled. I had this idea for Undoing time because of Beverly and because of the op-ed piece that she wrote that so eloquently compared her life as a black lesbian woman with a heroin addiction sewing US flags in a prison sweatshop to the mythology around Betsy Ross and the ideas of life, liberty and happiness that the flag purportedly guarantees. When I read the op-ed, I wanted to see Beverly’s words embroidered into all of the flags made at the flag factory at CCWF. Then I found out I could buy flags made in the sweatshop at CCWF from the prison industry authority (PIA). The PIA only sells to other state agencies, but, as a professor at the University of California, which is a state institution, I had access to purchase through their online catalogue. So I bought flags from the PIA and waited for Beverly to get out. When she was paroled out to Los Angeles, I went down to meet with her and make a video with her. I had this idea that I would pose her like Betsy Ross is posed in all those awful paintings where there’s the light coming in from the window behind her and she’s got the flag draped across her lap and she’s showing it to George Washington. My plan was to record her reading her op-ed piece and taking all the stitches out of one of the flags.Beverly Henry in Undoing Time.

I had a classroom at UCLA set up as a studio to do the shoot, and I had a former student meet me there to do camera and sound so I could focus on Beverly. I thought I could have her read her op-ed, but when we tried, it was just a disaster.

Dzur: Because it came across like a public service announcement?

Daniel: Yes. It was too stilted. And it made her nervous. She wasn’t an actor, though she was incredibly eloquent just on her own. So, I sat right behind the camera and we just had a long conversation. I’ve got six hours of video from that day.

We shot it in portrait format, because I knew I wanted it to be installed in portrait format, and at the end of the day I just asked her how she would feel about taking stitches out of one of the flags. And she said yes. She didn’t do it the way I imagined it.Dzur: She did it like a seamstress.

Daniel: Yes. She had done it before. That’s what they would have to do to a flag that was flawed. Like she says in the video, ‘I’m going to take this flag down’.

I didn’t tell her to talk or not to talk while she did it. We just filmed what she did, and it ended the way it ends in the video, when she tears the last few stripes of the flag apart and says, ‘you know in a way, this is what happens to the lives of the have-nots in America, they get shredded, I know because I was one of them’.Dzur: Prisons are domains that, to use your word, have an institutional polyphony and complexity that’s very hard to represent. The ethnographic approach is to get some insiders’ reports in order to open up the reality in a critical way. Yet, at the same time, this is a tricky process if one is a relatively privileged person from the outside. One tries to learn from incarcerated people about their realities and then put that together in a form that is truthful for the insiders but also brings outsiders into their world.

Daniel: Yes, exactly. I do come from a very privileged position, relatively speaking, and so in my projects I always try, in the introduction, to set a scene to expose my own positionality, to explain how I got inside the prison and how I got to talk to these women.

But yes, I definitely want to learn from the people I’m talking to and then create something out of that that is outward facing. So the community of people who have participated in these conversations are not the audience. They are the educators. They are the people who understand the systems they are trapped inside. The work that I make is for a general public labouring under a set of assumptions that are not accurate.

I often say that my idea of audience is modelled on my mother, who was a well-meaning. Christian, middle-class, suburban housewife who assumed that when people were incarcerated, it was because they’d done something wrong and that the punishment they were receiving was just.

I learnt by going into CCWF that this is not the case and it’s not just not the case in only a couple of cases, it’s not the case in like 97 per cent of the cases.

That’s the kind of idea I want to be able to get across to the general public. -

4. The responsibility of the artist

Dzur: There’s almost nothing good that one could say about the American criminal justice system, especially the prison, and yet you’ve been drawn to better understand and represent this reality for many years. What keeps you going back? And how do you feel that you’ve changed as a result of your continued exposure to a reality from which many other people would look away?

Daniel: I started this work, first, in collaboration with a needle exchange organisation in Oakland. It was down the street from where I was living in an artist loft in a former paint factory. I learnt about the criminal legal system a bit through interviewing injection drug users. They were mostly homeless heroin addicts and alcoholics who used the needle exchange and other services that this organisation provided. I got involved with the organisation because I heard the director on the radio talking about how the City Council representative, who was my City Council representative, was trying to kick them out of their facility in favour of a kind of gentrification project at the local Bay Area Rapid Transit Station.

I was interested in using media and information technology to create a productive conversation about the importance of needle exchanges but also about the problematic social construction of addiction and the failures of the public health system. I did a lot of writing for that project, which was titled ‘Blood sugar’. The phrase ‘don’t look away’ is at the core of this writing and the design of the interface. It was through my work with the ‘clients’ of the needle exchange that I witnessed the negative effects of over-policing and the way that poor people of colour were ground down by court system. People would be picked up and then they’d be put in jail and then they’d be released, and they’d have nothing – jail churn. Every turn of that cycle would leave them worse off than they were before.

Then I had the opportunity to work with a legal clinic organisation started by a student of Angela Davis. That’s the group that took me into CCWF.Dzur: What keeps bringing you back into the prison system, and what do you feel you’re learning as an artist?

Daniel: The first time I went on a prison visit and I met Beverly Henry, it really changed my life.

Dzur: How so?

Daniel: Before that I had a typical liberal distaste for prisons and a sense that the criminal legal system was likely not a fully just system and that it was possibly inflected by racism. But I had no experience in my life up to that point of meeting a person like Beverly and hearing her talk about her life and the lives of other women inside. It was just a profound experience for me.

At the same time, I’d been working with these folks at the needle exchange. I had conceived of this as a participatory media project in which the clients of the needle exchange would document their own daily experience with disposable cameras and cheap audio tape recorders and, together, we would make web pages about their lives using the media they had created. That fell apart for all sorts of reasons, including the fact that people living with addiction, whose lives are criminalised, have to spend most of their time just trying to survive. They wanted to be heard but they needed me to listen and take care of the rest.

In a context without universal healthcare, guaranteed housing and food security the criminalisation of self-medication is like the worst thing in our culture. It is both the worst thing and the most ignored. And I felt if I could do something to illuminate it and to try to change it, then I had a responsibility to do that. The only way I know how to do things is as an artist. I do see your point about the parallels with ethnography, but, of course, I don’t think like an ethnographer. My end goal is to advocate and persuade, and the difference is, like you pointed out, the deployment of the symbolic in the effort to communicate.Dzur: Beverly Henry’s presentation is powerful. Her face lights up as she talks. Here’s somebody who spent 40 years in prison for a non-violent offence. You can tell there’s a real fire there about the injustice of it. You know she suffered the injustice, but her affect and self-presentation are remarkable. I can see how you would be drawn to her.

Daniel: Yes, she’s extraordinary, but she’s not unusual. There were many women with very compelling stories and analyses, and I really wanted to treat them as theorists and scholars, as equal to the other people who were quoted in the project, like Frederick Jameson and Angela Davis and Giorgio Agamben. They had their own kind of anecdotal theoretical perspective and politics. Most of the women I talked to were very politically engaged, and they had an argument to make about the system and the injustices they had suffered both inside and outside the prison. Most weren’t saying, ‘Oh, I’m innocent. I didn’t do it, I didn’t do anything’; they were saying that structural inequalities had forced them to commit what I began to think of as ‘crimes of survival’. There was only one woman of the 25 who were included in Public secrets who claimed to be innocent, and she was just exonerated this year.

-

5. Ambushing people by art and challenging public culture

Dzur: Let me get back to this point that you made about how you think about your work as potentially reaching the audience of your mother. When you said this I thought of a lawn sign I see in a nearby neighbourhood that reads ‘One Nation Under God’, proudly displaying Christian nationalism. Such highly exclusionary ideas are successfully marketed by media firms like Fox, a company that has only grown more influential in our public culture in the last decade. It is the daily normal newsfeed for a lot of people. As an artist who works in media and seeks political conversation, how do you break through that worldview? And if you can’t, aren’t you preaching to the converted?

Daniel: I think the ‘preaching to the converted’ question is a really important one. Of course, when you make work for galleries and museums, that’s a much narrower public than the public in general. It’s likely that the ‘One Nation Under God’ person never goes to an art museum that would exhibit Beverly’s video and the installation of Undoing time flags, but they might.

Beverly’s piece was in an exhibition during the pandemic called ‘Barring freedom’ at the San Jose Museum of Art that was all work about the criminal legal system. Lots of people go there who wouldn’t have expected to see that work there. You can ambush people in art museums.Undoing Time.

But to get back to the core of the question, I make work that is available online so it will be accessible to a broader audience. Now how to get people to go to it online is another question. I like that it gets used in a pedagogical way. Public secrets was used a lot to teach about the criminal punishment system by colleagues I know and others that I don’t know.

Another tactic is to use the multivocality strategically. For example, I was afraid to tell my mother I was visiting a prison when I first started, because I knew her reaction would be, ‘That’s not safe!’ or ‘Why would you want to spend your time there?’ Eventually I told her about a woman I had interviewed over a period of time who had type 1 diabetes. My father also had type 1 diabetes, and it was brutal; it eventually destroyed every organ in his body. It was a very difficult and very significant part of our family life.

This woman had been sentenced to two years in an awful prison for writing bad cheques. She was diabetic and wasn’t getting a diabetic diet. They weren’t always giving her her insulin, so she was at risk of potentially developing diabetic neuropathy in one of her feet. The boots she was given to wear didn’t fit, so she was putting her sanitary napkins in her shoes to try to protect her toes because she didn’t want to have an amputation. There was another woman she told me about who had to have an amputation because of the non-diabetic diet and the irregularity of the insulin.

I told my mother that story and she couldn’t believe it. She couldn’t believe that a state institution would abandon these women to this disease. This shifted her thinking about the justness of the justice system. My mother was really interested in that story and moved by it because of her own life experience. That kind of connection to story, in the context of multiple, similar stories, can really challenge one’s assumptions and open one’s mind to new perspectives. I also think that hearing people’s actual voices can be really compelling and humanising, and that can provide an opportunity for an audience to have an experience that might be transformative for them.Dzur: You first started getting into this work via people you lived near who were injection drug users. Because of your interactions with them and then also your interactions with prisoners, your general liberal perspective started to change.

As you were talking about this shift in perspective, I was thinking about some public administration scholarship inspired by Foucault that pays close attention to how social problems are represented. In the case of injection drug use, the conventional representation is that some drugs make you addicted and the addiction makes you do things that are criminal and that harm yourself and others. But once you hear the stories of injection drug users, you move through the looking glass. And now, the problem is policing; the problem is the way that injection drug users are forced to inject in alleyways; the problem is social stigma and marginalisation.

This embodied way of representing social problems seems so far away from even conventional liberal thinking that it makes for a very difficult aesthetic project for the artist. You are opening up this world and inviting people in, and whether they do that or not is their responsibility.Daniel: Yes. Ultimately, a person or audience has to have some amount of openness for an artwork to change their thinking.

I try to use the introductions and conclusions to my projects to represent my own perspective as an artist and researcher, and through the design of the interfaces and architecture of the works I try to give the viewer the same kind of privileged experience that I’ve been able to have as the interviewer, learning about something like addiction. Blood sugar was structured around an examination of both the social and biological constructions of addiction – addiction as a construct, as a way that we think about a thing that we criminalise – and I brought a lot of social and political theory into my voice-over narration at the beginning and the fourteen ‘question texts’ that are linked to the interviews throughout the interface. I even use the looking glass as a metaphor in those passages where I talk about the way we all are already always on the drugs our bodies make.

I used these texts to describe and analyse how an addiction develops for an injection drug user and how the drug acts in the body, in order to point to criminalisation and the failure of the public health system as the real problem. Most of the people I spoke to started on heroin because they didn’t have health insurance and they couldn’t afford Prozac or painkillers or whatever it was that they actually needed. They needed something, because they were in some kind of pain. So why do we criminalise self-medication when we don’t provide universal healthcare?

I’m trying to make those kinds of arguments by illuminating the experiences of actual human beings who need help to survive, not punishment. -

6. Comparative perspective on American criminal justice

Dzur: You have spent time in Belgium working on Inside the distance. Has what you’ve experienced there been helpful to you in seeing American criminal justice in a different way?

Daniel: The American criminal justice system is the worst. I certainly think it’s much worse than the Belgian criminal justice system. It was really interesting to me to see that restorative justice is institutionalised in the system there, that the state will support the use of restorative justice mediation. Getting to meet the people who actually had written the bill that instituted the restorative justice practice as part of the system was really interesting for me.

I met one of the prison wardens in Leuven who told me that they never use solitary confinement for more than a few hours in a day and only in the most extreme circumstances or to keep a prisoner safe. The time spent in prison, even for murder, is seldom more than 13 years because they’ve learnt that there’s no productive effect to incarcerating a person beyond that time. To me, that’s comparatively so enlightened. It is like they live in a completely different world.

Of course, it’s a very small country. They don’t have states to deal with, and in terms of structure, it’s a very different system in so many ways. But it’s certainly more enlightened. I know they have problems there as well, such as overcrowding. I only got to visit two prisons there that were both relatively small. At the time Belgium was being officially criticised by European institutions and human rights organisations for overcrowding and conditions of confinement.

I learnt that most of the people who held leading positions in the prison system came out of criminology or sociology rather than policing. I think that makes a big difference in the way that incarcerated people are treated there. One of the guards I spoke with, who’d been in this prison for many years, said the newer, younger prison workers had more of a punitive attitude, but the older workers, were focused on care and rehabilitation as opposed to punishment.

Prison guards in California are highly paid because of the strength of the prison guards’ union. You only need a GED (a high school equivalency degree) to qualify. The training is from the perspective of policing. It’s about custody, not about care.Dzur: I was struck by something in Exposed, your recent piece on prison conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. One inmate, who’d been incarcerated for 20 years, said that in the span of his tenure, the prison culture shifted from a kind of bogus show of rehabilitation to absolutely no pretence of rehabilitation. Prison culture was all business. One knows this already from academic scholarship, but hearing people talk about it from the inside is powerful. This link to really hard-edged capitalism in the US seems like a sharp distinction between American and Belgian prisons.

Daniel: Definitely. When Arnold Schwarzenegger was governor of California, he added the word ‘rehabilitation’ to the CDC (California Department of Corrections) and made it the CDCR. Most activists here will use a small ‘r’ when they write that. Incarcerated people laugh at it. People at San Quentin get programming because it’s in the Bay Area and there’s a lot of scrutiny and there are a lot of volunteers setting up programmes and going in and out, but in the rest of the system it’s pretty bleak.

Dzur: Even during the pandemic, inmates are getting charged a couple of bucks out of their incredibly meagre personal budgets just to go to a clinic and see a clinician. What a public health disincentive!

Daniel: And a lot of people don’t have any money. People who have jobs have a small amount of money, and people who have families that can send them money may have money, but a lot of incarcerated people are completely indigent, and so they just don’t get healthcare. During COVID-19, it’s pretty bleak.

I’m working right now with one of the people who contributed to Exposed, Tim Young. He is on death row in San Quentin. We’re collaborating on a project about his wrongful conviction for a multiple murder in 1995. He has shared many details about what life is like on death row in San Quentin. He got COVID-19 in the first wave, pre-vaccination. He was terribly sick, and now he has long COVID symptoms. Prisoners who contracted COVID there, basically everyone in his unit, were just left in their cells unless they passed out.Dzur: Sometimes they were just left on the floor for hours.

Daniel: Yes, they were just dragging people out on the tier and leaving them. They set up a camp hospital in the yard there because they had so many cases. But you weren’t getting treatment unless you were on the verge of death. And they did have people die: 28 incarcerated men died at San Quentin.

-

7. Sources of hope: increased youth engagement in criminal justice

Dzur: What gives you hope? Scanning the horizon, what sources of inspiration

draw you in right now?Daniel: There are some things that give me hope. When I started Exposed, I assumed that the pandemic was going to last a couple of months, like most of us did. I continued to update that project on a weekly basis for almost two years. It was a lot of work, and after a few months I began to see that I needed help to do that weekly updating, so I offered internships to undergraduate students. It was very tedious work like scanning through articles to try to find quotes and watching local news reports to try to find interviews with incarcerated people, and then copying and pasting them into a spreadsheet.

I was surprised at how many students were willing to help on that project. Over the period of a year, I had over 20 enrolments, and some students enrolled two or three times to help with that project. When I would ask them, ‘Why are you interested in doing this work?’ they would all say things like ‘I want to help end mass incarceration’ or ‘I’m a prison abolitionist’.

Three years ago, I didn’t hear many students saying things like that.Dzur: I think you can credit Black Lives Matter activism for that shift.

Daniel: Yes, a lot definitely. And also, I think there’s more and more cultural production around criticisms of the criminal legal system, particularly because of Black Lives Matter and the awareness of structural racism that has opened up.

Dzur: We began this conversation talking about how you had gone to Leuven to do an exhibit, and then you got involved in the project that became Inside the distance. You were drawn to mediation as a kind of productive space, a space of relationship and closure, a space of healing, and a number of other positive qualities.

From the perspective of an American who’s fed up with the criminal justice system and is on critique mode all the time, to see this sort of positive space emerge is really appealing. I wonder if that’s happening with your students too, that they’re also drawn to think about justice, but are tired of non-stop critique and want to build spaces that work. I wonder if part of what’s bringing young people in is that they see something constructive, something they can do.Daniel: Yes, they definitely want to do something, and I think they see abolitionism as a position that recognises that change has to be complete: we can’t tinker with the system we have now enough to make it just. They’re seeing abolition in a holistic way: it’s about policing; it’s about criminalisation; it’s about incarceration; it’s about racism; it’s about fundamental inequities, and segregation. It’s a holistic position about radical change.

I think that is what art can do: it can expose injustice and make radical demands.Dzur: Uncovering the work, the practice involved in radical change, is another thing art can do. Abolition can be thought of as nothingness, in the same way that anarchism is often misconstrued as the absence of law rather than the presence of new relationships and new norms. In the Belgian context, you see people making and institutionalising new norms. Inside the distance shows that this is not easy work. It’s not just the absence of things, it’s the presence of some pretty difficult work. I think students understand that about the task of moving beyond prison.

Daniel: I’m teaching a class now, which is the other thing that gives me some hope. I got involved with Tim Young, the gentleman on death row who was wrongfully convicted, because he was willing to contribute so regularly to Exposed. But we started talking about his case, and I became convinced of his innocence. The trope of innocence is a problem; it’s like the flip side of criminalisation, and I’d never thought about focusing my work on innocence or on an individual case, but once you get to know someone who’s wrongfully convicted on death row more practical ethics come into play.

Tim and I decided we would work together on a documentary project about his case but with a larger framework focused on identifying and analysing all the ways in which official misconduct leads to wrongful convictions. To do that, we compare his case to the cases of other Black, death row prisoners who have been exonerated to reveal the pervasiveness of various different kinds of official misconduct – like withholding exculpatory evidence and witness tampering in causing wrongful convictions. In my research for this project, I’ve listened to a lot of podcasts about wrongful convictions. On one I heard two lawyers and Georgetown University professors, Mark Howard and Marty Tankleff, talking about a class they were teaching at Georgetown called ‘Making an exoneree’, in which undergraduates re-investigate and make short documentary films about potential cases of wrongful conviction.

They use these short documentary films to help their ‘clients’ find top-notch pro bono representation to contest their convictions. Tim has a court-appointed attorney who took over fifteen years to file the opening brief in his appeal. He definitely needs pro bono representation. I contacted the Georgetown professors, hoping that the class would take on Tim’s case and that I could learn how to teach a class like ‘Making an exoneree’ at UCSC. We ended up deciding to join forces, and last winter and spring quarters ten undergraduate film students at UCSC worked with fifteen Georgetown undergraduates (where there is not a film major) to reinvestigate and document five cases of wrongful conviction.Dzur: Virtual collaboration is something that has become much more accessible during COVID-19.

Daniel: Yes. Their class meets from 9:30 to 2:30 in Georgetown, and my class meets from 9:30 to 2:30 in Santa Cruz, so we have a two-hour overlap. They have been teaching this since 2018, and they have a roster of fascinating guests who volunteer to speak to the class and to help with the investigations. The professors, Mark and Marty, were actually childhood friends. Marty was wrongfully convicted for the murder of his parents. After he became a lawyer, Mark helped with Marty’s exoneration case. Then Marty became a lawyer, and he’s now an adjunct professor at Georgetown, a lawyer at a private firm and an important figure in the exoneree community and Innocence Project community.

We took Tim’s case this year as one of the five cases, and we’re taking on five new cases next year. The way that the students committed themselves to that work was also very hopeful and inspiring to me.

It’s about educating a lot of new young energetic abolitionists.Dzur: And maybe figuring out how to ban Fox News?

Daniel: Yes, that would be great.

Sharon Daniel is a digital media artist and a professor in the Film and Digital Media Department and the Digital Arts and New Media MFA programme at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where she teaches classes in digital media theory and practice. She creates interactive and participatory documentary artworks addressing issues of social, racial and environmental injustice, with a particular focus on mass incarceration and the criminal justice system. Her work is located at the nexus of art and activism, theory and practice. Over the course of her career she has produced two distinct but related forms of internet art – participatory media platforms and interactive new media documentaries. While this work is often expanded into interactive installations, which have been exhibited in museums and festivals internationally, Daniel’s core practice is the development of innovative online interfaces to databases of original interviews and participant-generated content. Documentation of exhibitions and links to projects can be found at http://sharondaniel.net.