-

1. Introduction

Remembering in-group suffering may have ambivalent consequences for restorative justice initiatives in post-conflict societies. When collective narratives of intergroup violence exclusively emphasise in-group suffering, they may contribute to the further fuelling of the conflict (Noor, Shnabel, Halabi & Nadler, 2012; Schori-Eyal, Klar, Roccas & McNeill, 2017; Wohl & Branscombe, 2008). On the other hand, if narratives are focused on shared suffering and mutual forgiveness of the harm caused, they may facilitate peaceful coexistence (Salomon, 2004; Vollhardt, 2009). In this study, we examined the effects of reminders of political violence on the desire for intergroup revenge and to what extent an apology by in-group representatives (Basque government) can alleviate the negative effects of those reminders. We further tested to what extent attributions of responsibility for political violence, distributed among three types of agents (namely, Basque nationalism, Euskadi Ta Askatasuna or ETA and its environment, and police forces and the Spanish state), as well as in-group victimhood, explained these effects.

This study presents a number of relevant contributions. First, in the current experimental study we focus on the impact of narratives of the past (reminders of political violence, with and without an apology) as a motivation to support seeking revenge against the adversary. Only scarce research has focused on revenge as an element of intergroup relations. However, revenge can play an important role in escalating and/or maintaining intergroup conflicts. In general terms, revenge can be considered a component of retribution (Gerber & Jackson, 2013; Von Hirsch, 1976), defined as a less constructive use of punishment and as a desire to make the offender or the opponent suffer. Revenge towards the adversary can also be a form of vicarious retribution, as revenge for an assault or provocation that had no personal consequences but that harmed a fellow in-group member (for a review, see Lickel, Miller, Stenstrom & Denson, 2006).

Second, we test how direct reminders of political violence without an apology, as compared to reminders of political violence accompanied by an apology, incite or attenuate the desire for intergroup revenge, through different ways of responsibility attribution as well as beliefs about the victimised group. Once a collective traumatic event takes place, people resort to defensive responses, that is, biased responsibility attributions and perceptions of in-group victimhood, as explanatory mechanisms for further fuelling cycles of revenge and violence against out-groups (Lickel et al., 2006; Rouhana & Bar-Tal, 1998; Salomon, 2004). Only few studies have examined responsibility attributions and in-group victimhood in tandem.

Third, we study the collective memory processes as they apply to a within-group conflict. That includes instances of state violence perpetuated by governmental, military or political authorities or by terrorist groups against the citizens of a country, where the line between the perpetrator and the victim group is blurred and the ‘sides’ of the conflict are somewhat difficult to define (Bobowik et al., 2017). Also, the victim and perpetrator categories may be difficult to define, especially when both sides view their in-group as the victim and the out-group as the perpetrator. This type of intergroup bias is referred to as ‘divergent construal’ (Ross & Ward, 1995).

Fourth, the effectiveness of institutional apologies has received scarce and mixed empirical support (for reviews, see Blatz & Philpot, 2010; Blatz, Schumann & Ross, 2009; Hornsey & Wohl, 2013). Studies that have examined these effects with representative, or at least geographically diverse samples, are practically non-existent (but see Wohl, Matheson, Branscombe & Anisman, 2013). In the present research, we analyse the effects of reminders of past political violence with random representative samples, through an experimental design (comparing no reminder condition with reminders of political violence without an apology, and the latter with reminders with an apology) and in real-life settings of the Basque Country, where severe transgressions took place in the recent past and where Basque governmental representatives officially apologised for the treatment (i.e. abandonment) of the Basque victims of terrorism in the Basque Country. To our knowledge, little research (Bobowik, Bilbao & Momoitio, 2010; Valencia, Momoitio & Idoyaga, 2010) has examined such cases of apology.1.1 Reminders of in-group suffering, attributions of responsibility, in-group victimhood, and intergroup revenge

In the same way as remembrance of significant historical events is important for group continuity, passing on the narrative of victimisation from generation to generation is often a collective mandate as in the saying that nations that forget their past are doomed to repeat it (see Barkan, 2000). Empirical evidence has suggested that reminders of ingroup suffering may result in defensive responses and thus have negative effects on intergroup relations (e.g., Wohl & Branscombe, 2008).

In-group victimhood, a possible mediating mechanism of these effects, involves a strong belief in the uniqueness of the group’s trauma combined with a strong sense of mistrust of out-groups (Bar-Tal & Antebi, 1992; Schori-Eyal et al., 2017). Perceptions of in-group victimhood have been recognised as one of the elements that make a conflict intractable and resistant to resolution (Rouhana & Bar-Tal, 1998). Indeed, research confirms that perceptions of in-group victimhood are associated with the belief that one’s group is allowed to morally transgress, associated with the further legitimising of doing harm against out-groups (e.g. military actions; Schori-Eyal et al., 2017).

Another explanatory mechanism of how in-group victimhood perceptions are fuelled may be biased attributions of responsibility for collective harm. Recent research confirms that the perception of in-group victimhood is associated with less accurate recall of information about the suffering of the out-group (Schori-Eyal et al., 2017). That is, one of the main correlates of in-group suffering narratives is their implied delegitimisation of the ‘other’s’ collective narrative of pain and suffering (Salomon, 2004), whereas the in-group’s suffering is perceived as unique and more severe than other similar events in history (Noor et al., 2012; Schori-Eyal et al., 2017). Such defensive responses reflect people’s natural tendency to minimise the out-group’s suffering in order to justify the in-group’s aggressive behaviour (Branscombe & Miron, 2004).

Thus, we expect that the reminders of political violence perpetrated in the Basque Country (both by the ETA and the Spanish state) that remain without an apology will increase defensive responsibility attributions, that is, to police forces and the Spanish state, and thus reinforce in-group victimhood (an indirect effect hypothesis). Further, such reminders will strengthen the desire for intergroup revenge through these defensive responsibility attributions, resulting in increased in-group victimhood (a sequential indirect effect hypothesis).1.2 Institutional apologies and overcoming the past: the role of attributions of responsibility and in-group victimhood

In recent decades, intergroup apologies have emerged as a successful instrument for promoting justice for historic wrongdoings (Marrus, 2006). The acknowledgement of responsibility by the perpetrators should help them assimilate negative past misdeeds and decrease their defensive attributions, whereas among the victims it should help reconstruct their collective esteem (Bilali, 2012; Shnabel & Nadler, 2008). Nevertheless, the effectiveness of institutional apologies still remains under question (see Blatz et al., 2009; Blatz & Philpot, 2010; Blatz & Ross, 2012; Hornsey & Wohl, 2013; Hornsey, Wohl & Philpot, 2015 for reviews). Whereas some studies have proven their effectiveness under specific circumstances (Brown, Wohl & Exeline, 2008; Leonard, Mackie & Smith, 2011), others brought equivocal or limited evidence (Ferguson et al., 2007; Nadler & Liviatan, 2006; Philpot, Balvin, Mellor & Bretherton, 2013; Philpot & Hornsey, 2008, 2011; Steele & Blatz, 2014; Wohl, Hornsey & Bennet, 2012; Wohl et al., 2013). Particularly, research on real-life apologies for severe transgressions usually provides a more pessimistic outlook (Ferguson et al., 2007; Philpot & Hornsey, 2011; Wohl et al., 2013), as compared to research involving fictitious and mild apologies, and/or within a university population (Brown et al., 2008; Leonard et al., 2011). For instance, in Canada, apologies resulted in lower willingness in the victim group to forgive over time (Wohl et al., 2013). In the same vein, the presence of the apology for transgressions during Second World War failed to promote forgiveness for the offending group (Philpot & Hornsey, 2011).

Further, existing research has mostly examined intergroup apologies, where both sides of the conflict are clearly defined. However, in contexts that suffered under dictatorships or from internal political violence, the line between the groups involved is blurred and it may be more difficult to study the effects of an apology separately, juxtaposing the victims and the perpetrators. In fact, in most violent conflicts the adversaries involved are characterised by ‘dual’ social roles as both victims and perpetrators (SimanTov-Nachlieli & Shnabel, 2014). Still, most of the existent research focuses on groups with a clearly defined victim or perpetrator role, and little is known about restorative justice processes among groups with such a ‘dual’ victim-perpetrator role. Finally, only scarce research examined such cases of apologies in these ‘dual’ or ‘blurred’ contexts (but see Bobowik et al., 2010, 2017; Valencia et al., 2010).

There are many factors that may erode or boost the efficacy of institutional apologies. The acknowledgement of responsibility for in-group actions that intentionally provoked out-group suffering is one of the key characteristics expected to improve the positive impact of apologies (Blatz & Philpot, 2010; Hornsey & Wohl, 2013; Wohl, Hornsey & Philpot, 2011). For instance, McGarty et al. (2005) showed that group-based guilt and perceived responsibility for the mistreatment of the Indigenous people in Australia predicted support for a governmental apology among non-Indigenous Australians. Further, a study showed that when apologies were accompanied by an acknowledgement of out-group’s continued suffering, Belgians presented more positive attitudes towards past colonial victims (Lastrego & Licata, 2010). Berndsen, Hornsey and Wohl (2015) found that an intergroup apology expressing understanding of the victimised group’s suffering (as compared to an apology focused on the perpetrator’s feelings) had a positive effect on intergroup trust, and thus intergroup forgiveness. Together, apologies are expected to help collective healing because they manage to create an integrated historical narrative that highlights both mutual misdeeds and suffering (Gibson, 2004; Páez, 2010).

Finally, previous research has shown that an apology decreases a desire for intergroup retribution (Brown et al., 2008; Leonard et al., 2011). We therefore expect that (compared to the reminder of political violence without an apology) reminders of political violence accompanied by an apology will decrease responsibility attributions to police forces and the Spanish state and thus in-group victimhood (a simple indirect effect hypothesis), and also attenuate the desire for revenge through responsibility attributions to ETA and Basque nationalism and thus decreased in-group victimhood perceptions (a sequential indirect effect hypothesis).1.3 Current study: the Basque case

The context for this investigation was the autonomous region of Spain known for its political violence: the Basque Country. The political conflict over this region’s independence is the longest enduring in Western Europe. The Basque Country has maintained some levels of self-governance during the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, however, still under different Spanish political mandates. After the Spanish Civil War, General Franco established dictatorship where any forms of democracy, Basque culture or self-governance were suppressed and prohibited. An armed leftist Basque nationalist and independentist organisation, Euskadi ta Askatasuna (ETA), emerged in 1959 in response to the repression during the dictatorship. Over the decades of this conflict, the ETA caused 837 deaths, and hundreds of people were kidnapped or injured. During the dictatorship and long after it ended, right-wing parapolice groups, namely, the Basque Spanish Battalion (BVE) and the Antiterrorist Liberation Groups (GAL), as well as Spanish and autonomous police forces, also caused harm, with more than a hundred deaths and injuries during protests, and thousands of torture allegations which are currently under investigation (Carmena, Landa, Múgica & Uriarte, 2013). After the dictator’s death and the establishment of the Spanish Constitution, the Basque Country regained its autonomy, although not broad enough to satisfy the Basque nationalists. A part of Basque nationalism continued supporting the armed movement ETA. Since then, the conflict has persisted, causing the death of hundreds of people and suffering of many more (Espiau, 2006). On 5 October 2007, the Basque Government and Parliament (though not supported by radical Basque nationalists) officially asked victims of terrorism in the Basque Country for forgiveness for ‘the abandonment and oblivion they have suffered for too many years’ (The Basque Parliament, 5 October 2007).

In October 2011, ETA declared the cessation of their armed activity. Following the announcement (Euskobarometer, 2011), nearly half of the Basques reported trust in the sincerity of ETA’s announcement, 68 per cent were optimistic about the end of terrorism and 81 per cent believed that political goals in the Basque Country could be defended without resorting to violence. Interestingly, when it comes to political ideology, the Basque Country is greatly nationalistic (49 per cent of Basques define themselves as nationalists). With regards to ethnic/national identification, at the time of data collection 50 per cent identified as only Basque or as more Basque than Spanish, 37 per cent as both Basque and Spanish, whereas only a minority (12 per cent) identified as Spanish or preferably Spanish (Euskobarometer, 2011). These statistics reflect that the Basque society has a strong national identity but is still divided over nationalistic narratives that dwell on the repressive practices of the Spanish state and that legitimise the use of violence (Martín-Peña & Opotow, 2011; Varela-Rey, Rodrígez-Caballeira & Martín-Peña, 2013), and the narratives of suffering caused internally by ETA. In this sense, emphasising in-group victimhood may serve as a pervasive justification of negative attitudes towards the adversary and further rationalise the use of violence. The context of our study resonates with the example of cases of vicarious retribution provided by Lickel et al. (2006).1.4 Hypotheses

Together, we tested the following specific hypotheses:

H1a: Compared to no reminder condition, reminders of political violence perpetrated by different agents in the Basque Country without an apology will reinforce responsibility assignment to police forces and the Spanish state and decrease responsibility assignment to the ETA and Basque nationalism, as well as increase the perceptions of in-group victimhood and intergroup revenge.

H1b: Compared to reminders of political violence without an apology, reminders of political violence accompanied by an apology will decrease responsibility assignment to police forces and the Spanish state and increase responsibility assignment to ETA and Basque nationalism and also decrease perceptions of in-group victimhood and support for intergroup revenge.

H2a: The effect of reminders of political violence without an apology on intergroup revenge will be explained (i.e. mediated) by increased in-group victimhood.

H2b: The effect of reminders of political violence with an apology on intergroup revenge will be explained by decreased in-group victimhood.

H3a: Compared to no reminder condition, the effect of reminders of political violence without an apology on intergroup revenge will be sequentially explained by increased responsibility attributions to police forces and the Spanish state and decreased responsibility attributions to ETA and Basque nationalism and thus increased in-group victimhood.

H3b: Compared to reminders of political violence without an apology, the effect of reminders of political violence with an apology on intergroup revenge will be sequentially explained by decreased responsibility attributions to police forces and the Spanish state and increased responsibility attributions to ETA and Basque nationalism and thus decreased perceptions of in-group victimhood. -

2. Method

2.1 Participants and data collection

The data were collected in December 2011 in the Basque Country, an autonomous region of Spain. A random sample of 259 Basque adults aged from eighteen to 60 (50 per cent female; M age = 40.86, SD = 11.12) was obtained through a probability sampling procedure stratified by age and gender in the capitals of the three provinces of the Basque Country Autonomous Region: Bilbao, Vitoria, and San Sebastian. Selection of the participants was based on population records in each of the three cities by the municipal population data obtained from the Basque Institute of Statistics (Eustat, 2011). All participants were born in one of the three provinces of the Basque Country Autonomous Region (51 per cent in Bizcaya, 18.7 per cent Álava and 30.4 per cent in Guipúzcoa) and were identified as Basque (see Table 1), suggesting that our sample was composed of Basque participants.

The participants were recruited for an interview by random routes with a defined starting point in a randomly selected street and according to a set of predefined rules to select a household. Namely, each interviewer would select every third household in each building on the street. All respondents had to be registered in the census of the municipality where the interview was carried out and were residents of the particular households where they were interviewed.

Detailed socio-demographic characteristics of the final sample per experimental condition are presented in Table 1.Table 1 Socio-demographic characteristics and descriptive data across the three experimental conditionsNo reminder condition Reminder without an apology condition Reminder with an apology condition n 100 80 79 Age M (SD) 41.1 (10.9) 41.2 (11.9) 40.2 (11.3) Sex (per cent) Female 50.0 50.0 50.6 Household income (per cent) ≤600€ 3.3 2.7 13.0 601-1,800€ 52.7 58.7 68.8 1,801-3,000€ 34.1 32.0 14.3 ≥3,000€ 9.9 6.7 3.9 Education (per cent) Primary education 5.0 17.5 20.3 Secondary education 30.0 12.6 19.0 Professional studies 37.0 35.0 32.9 University education 28.0 35.0 27.8 Religion Catholic 60.6 52.5 54.5 Indifferent or atheist 38.4 46.3 41.6 Other 1.0 1.3 3.9 Native language Spanish 87.0 93.8 88.6 Basque (Euskera) 13.0 6.3 11.4 M (SD) Political orientation (right wing) 3.97 (1.48) 3.58 (1.60) 3.92 (1.84) Basque Identity 6.07 (1.42) 6.03 (1.29) 5.78 (1.57) Spanish Identity 3.77 (2.11) 3.36 (1.96) 3.81 (2.15) 2.2 Procedure and materials

Respondents participated in a fully structured, face-to-face interview. The data were collected by a team of trained interviewers who were provided with detailed fieldwork instructions. Participants were told that they were taking part in a study on the memory of recent historical events in the Basque Country and were randomly assigned to one of the three experimental conditions. In the political violence condition (see Appendix 1), participants were asked to read an informative text which came from a TV documentary about the consequences of political violence in the Basque Country and the political conflict that followed the Spanish Civil War. Importantly, the narrative presented information that most of the victims were killed by ETA, some by paramilitary groups or death squads such as Basque Spanish Battalion and Antiterrorist Liberation Groups and others by Spanish National Police. In the apology condition, the same information was presented with additional information on the petition for forgiveness issued by the Basque Parliament and Government directed to the victims of political violence in the Basque Country (Basque Radio-television EITB, 2007). In the control baseline condition, participants did not read any information and were directly instructed to fill in the questionnaire. In the two experimental conditions, participants were additionally informed they would be presented with extracts from a TV documentary.

First, all participants were asked their basic socio-demographic information. Then, in the experimental conditions, they received a questionnaire with the text on the first page and were asked to read it carefully in order to form the most correct opinion about it. Participants were also informed that later they would be asked to answer questions and summarise what they remembered from the text. They were asked to take all the time they needed to read the text. After reading the informative text, participants were further interviewed, responding to measures described in the following sections (dependent and socio-demographic variables of the study).2.2.1 Manipulation checks

To check whether our experimental manipulation worked, we measured the perceived volume of political violence across the three conditions. Participants were asked to indicate how much political violence people in their country were exposed to, on a scale from 1 (none) to 10 (a lot). In order to examine perceptions of narratives in both experimental conditions, we measured to what extent participants perceived the bogus article as trustworthy. Namely, participants were evaluated on a seven-point scale and the text was: from an unreliable source vs. from a reliable source, tendentious vs. neutral, not credible vs. credible, not describing facts vs. describing facts and negative vs. positive. To verify whether our manipulation activated the in-group and out-group categories as well as made salient the in-group suffering, we also analysed the relationship between open-ended questions referring to the in-group, the out-group and the in-group suffering, described in the following sections.

2.2.2 Group identification variables

Following Schori-Eyal’s procedure (2017), after evaluating the article (or after reading the general study instructions in the control group), participants were asked to define the in-group, that is, the group they believe they belong to in social and/or political terms (e.g. Basque nationalists, Spanish constitutionalists, cosmopolitan internationalists, right-wing Spanish or Basque nationalists, leftist Basque nationalists or non-nationalist left, etc.). They were instructed to think about the associations they use when speaking of ‘us’. More than half of the participants (51.5 per cent) defined themselves as Basque nationalists (and, in fact, 49.4 per cent as Basque nationalist left), 12.4 per cent as apolitical and 16.6 per cent as not nationalist left. In terms of left- right-wing political orientation, together 66 per cent referred to left-wing orientation as a political in-group category.

2.2.3 In-group victimhood

Next, participants were asked to think about a group trauma to make the in-group suffering salient. Following Schori-Eyal’s procedure (2017), participants were instructed to recall a past event in which the in-group (they previously defined) had been harmed, victimised and abused by another group and to describe it. We categorised these narratives to identify the agent responsible for the harm done to the in-group. Almost half of the sample (39.4 per cent) referred to the Spanish state as the responsible agent for the in-group suffering. Among these participants, 30.4 per cent wrote about the lack of freedom of expression, 17.6 per cent about the oppression of their language and culture, 13.7 per cent about diverse forms of state violence (e.g. police abuses), 12.7 per cent about the lack of right to self-determination, 10.8 per cent referred to oppression during Franco’s dictatorship and 7.5 per cent to illegalisation of independent political parties. Among those who referred to the ETA and its environment (17.8 per cent), a majority referred directly to the terrorism of the ETA and its environment (58.7 per cent), to the lack of freedom of expression (30.4 per cent) and to the nationalist radical left (izquierda abertzale, 8.7 per cent). Finally, 17.4 per cent mentioned diverse type of responsible and 25.5 per cent responded that their in-group was not harmed in any way or was harmed in other ways.

Next, participants were asked to fill in a short three-item version of the Perpetual In-group Victimhood Orientation Scale (Schori-Eyal et al., 2017). Participants indicated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) to what extent they agreed with the following phrases related to the perceived experience of collective harm by their in-group: ‘Our existence as a group and as individuals is under constant threat’, ‘No group or people have ever been harmed as we have’, ‘As they have harmed us in the past, so will our enemies wish to harm us in the future’. The scale has also obtained satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.85).2.2.4 Attributions of responsibility for political violence

Later, participants were asked to fill in the second part of the questionnaire where they were questioned about their attributions of responsibility for political violence to the in-group and to the out-group. For this purpose, we asked participants to also define the reference out-group as opposed to the in-group they defined earlier in the questionnaire. Participants were given the following example: ‘If you are a Basque nationalist, then Spanish constitutionalists would be an opposing group’. They were instructed to think of the words they would use most often when speaking of ‘them’. In this case, 35.5 per cent mentioned Spanish nationalism (also called españolismo or Spanish right wing); 18.5 per cent referred to right-wing and extreme right-wing groups; 15.4 per cent to radicals or extremists in general and 5 per cent to nationalism in general; 10.8 per cent mentioned Basque nationalism (including Basque radical nationalism or izquierda abertzale); 9.3 per cent mentioned other types of groups, whereas 5.4 per cent responded that there was no group they felt opposed to. After the induction, participants were asked: ‘To what extent were the following agents responsible for political violence?’ The answers were given on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely yes). We measured two types of attributions of responsibility for political violence. Responsibility attributions to ETA and Basque nationalism were defined by two items: ‘Basque nationalism’ and ‘ETA and its environment’. However, these items correlated weakly (r = 0.29) and thus were treated as separate variables in the subsequent analyses. Responsibility assignment to police forces and the Spanish state (α = 0.76) was measured with three items: ‘Spanish nationalism’, ‘national police and Civil Guard’ and ‘parapolice groups and extreme right wing’.

2.2.5 Intergroup revenge

Finally, participants filled in a six-item Intergroup Revenge Scale (α = 0.94) adapted to intergroup level from Revenge Motivations subscale of Transgression-Related Interpersonal Motivations Scale (McCullough et al., 1998). It measured the willingness to retaliate (e.g. ‘We’ll make them pay’) on a scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree).

2.2.6 Socio-demographic variables

We also measured age (continuous in years), sex (1 = male, 2 = female), education (4 levels, ranging from no education completed to a university degree), as well as political orientation (on a scale ranging from 1 ‘left wing’ to 10 ‘right wing’) to check for possible confounding effects and control for them. We also measured place (province) of birth, native language (Spanish or Basque), identification with Basques and Spaniards (‘Where would you position yourself in your Basque/Spanish identification?’ on a scale from 1 ‘not at all Basque/Spanish’ to 7 ‘very Basque/Spanish’) to ensure ourselves that our sample was composed of people not only born in the Basque Country but also with a strong feeling of Basque identity.

2.3 Analytical strategy

To check for the effectiveness of our manipulation, we ran ANOVAs with Sidak post hoc comparisons and chi-square tests. To test for the main effect of experimental manipulations, we carried out ANCOVAs, controlling for political orientation. In order to test specific hypotheses, we applied planned comparison contrasts. Namely, for each ANCOVA, we applied two contrasts: the first contrast compared the reminder without an apology condition (coded as 1) with the no reminder condition (coded as –1, whereas the reminder with an apology condition was coded as 0). The second contrast compared the reminder with an apology condition (coded as 1) with the reminder without an apology condition (coded as –1, whereas the no reminder condition was coded as 0).

In order to test for hypothesised indirect effects, we used structural equation modelling using Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). The estimation procedure applied was maximum likelihood. Standard errors and the confidence intervals for indirect effects were derived from the distribution based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples. In this model, experimental manipulation variable was categorised into two dichotomous variables using backward difference coding procedure (see Cohen, Cohen, West & Aiken, 2003; Davies, 2010; Hayes, 2013; Hayes & Preacher, 2014). In this coding system, the mean of the dependent variable for one level of the categorical variable is compared to the mean of the dependent variable for the prior adjacent level. In our study, in the case of the first dichotomous variable, labelled ‘reminder without an apology versus no reminder’, the reminder without an apology and reminder with an apology conditions were coded as 1 and control as 0, and thus the reminder without an apology condition was compared to the no reminder condition. Second dichotomous variable, labelled ‘reminder with an apology versus reminder without an apology’, compared the reminder with an apology condition to the reminder without an apology condition, by coding the reminder with an apology condition as 1 and the reminder without an apology and no reminder conditions as 0. In our SEM model, these two independent variables predicted responsibility attributions and in-group victimhood, which were two sequential mediators in the model. Further, in-group victimhood predicted intergroup revenge, the dependent variable in this model. Political orientation was again introduced in the model as a covariate. We used the conventional goodness-of-fit criteria to assess the model fit: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) ≥ 0.90, a Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.06 and a Standardised Root-Mean-Square Residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.08 (see Hu & Bentler, 1999). -

3. Results

3.1 Manipulation checks

When presented with reminders of political violence without an apology, participants perceived significantly higher levels of political violence (M = 5.41, SD = 2.17; F (2, 256) = 3.09, p = 0.047, η2 = 0.02) as compared to the no reminder condition (M = 4.66, SD = 1.98). The perception of intensity of political violence in response to reminders with an apology did not differ from the other two conditions (M = 5.15, SD = 2.08). Also, when presented with reminder of political violence either without an apology or with an apology, participants evaluated the informative text as coming from a reliable source (F (1, 157) = 0.15, p = 0.699, η2 = 0.00, M = 4.49, SD = 1.71 and M = 4.38, SD = 1.77, respectively), neutral (F (1, 157) = 0.02, p = 0.893, η2 = 0.00, M = 4.13, SD = 1.63 and M = 4.09, SD = 1.78, respectively), credible (F (1,157) = 0.03, p = 0.866, η2 = 0.00, M = 4.41, SD = 1.67 and M = 4.37, SD = 1.73, respectively) and describing facts (F (1, 157) = 0.004, p = 0.949, η2 = 0.00, M = 4.56, SD = 1.66 and M = 4.54, SD = 1.89, respectively), with all mean scores above the theoretical midpoint (4). Importantly, a reminder accompanied with an apology was evaluated as significantly more positive (M = 4.33, SD = 1.57; F (1, 157) = 10.80, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.06) than the reminder without an apology (M = 3.51, SD = 1.57).

Further, we examined whether our experimental manipulation activated in-group and out-group categories as well as made salient in-group suffering. A chi-square test of independence showed that the relationship between experimental manipulation and defining one’s in-group as Basque nationalists (versus other in-group categories) was significant, χ2 (2, N = 259) = 7.70, p = 0.021. The analysis of adjusted standardised residuals revealed that participants exposed to a reminder of political violence with an apology were less likely to define themselves as Basque nationalists (z = –2.30), whereas they were more likely to define their in-group in these terms when presented with reminders without an apology (z = 2.40). No significant effects were found in the no reminder condition (z = –0.10).

A chi-square test of independence also revealed a significant relationship between experimental manipulation and the type of in-group suffering narrated in the open-ended question, χ2 (6, N = 259) = 19.35, p = 0.004. In order to interpret this finding, we again performed the analysis of adjusted standardised residuals. In this case, we found that, participants exposed to reminders with an apology were less likely to narrate wrongdoings committed by the Spanish state (z = –2.20), whereas they were more likely to express that they did not feel harmed as a group by anyone or narrate other type of suffering not related to political violence in the Basque Country (z = 2.10). In turn, when presented with reminders of political violence but without an apology, participants were more likely to report suffering caused by the Spanish state (z = 4.00) but less likely to narrate being victimised by different types of agents (e.g. both ETA and the Spanish state) (z = –2.10) or by anyone or other type of agents (z = –2.30). No effects were found in the no reminder condition.3.2 Preliminary analyses

No significant relationship was found between sex, age, education, native language and income and the dependent variables (responsibility attributions, in-group victimhood and intergroup revenge) and these socio-demographic variables were therefore not considered in further analyses. All analyses were adjusted for political orientation, which was correlated significantly with most of the dependent variables.

3.3 Effects of framing political violence on attributions of responsibility for political violence

All unadjusted means and standard deviations per condition and correlations between the dependent variables are presented in Table 2.

ANCOVAs revealed a significant effect of experimental manipulation on attributions of responsibility to the Basque nationalism, F (2, 252) = 4.03, p = 0.019, η2 = 0.03. Planned contrast analyses showed that participants exposed to reminders without an apology made less attributions of responsibility to Basque nationalism (M = 2.37, SE = 0.14) compared to participants not exposed to reminders (M = 2.89, SE = 0.12, t = –2.80, p = 0.006, 95% CI: –0.887 to –0.152), whereas these attributions were marginally higher among those exposed to reminders with an apology (M = 2.74, SE = 0.14, t = 1.90, p = 0.059, 95% CI: –0.014 to 0.758), compared to those presented with reminders without an apology.Table 2 Means and standard deviations per condition and correlations between the dependent variablesControl Political violence narrative Apology narrative 2. 3. 4. 5. 1. Attributions of responsibility to Basque nationalism 2.89 (1.34) 2.36 (1.10) 2.73 (1.19) 0.29*** –0.16** –0.39*** –0.12+ 2. Attributions of responsibility to ETA and environment 4.60 (0.74) 4.01 (1.22) 4.24 (0.99) 0.01 –0.13* 0.09 3. Attributions of responsibility to police forces and the Spanish state 4.12 (0.79) 3.97 (0.83) 3.81 (0.87) 0.25*** 0.11+ 4. In-group victimhood 2.93 (1.51) 3.95 (1.63) 3.48 (2.02) 0.29*** 5. Intergroup revenge 1.37 (0.73) 1.76 (1.14) 1.70 (1.32) Note. ** p < .01; ** p < .001; + p < .10.

In the same vein, we found significant differences between experimental conditions in attributions of responsibility to ETA and the environment, F (2, 253) = 6.49, p = 0.002, η2 = 0.05. Planned contrast analyses showed that responsibility attributions to ETA and related environment again were lower among participants shown reminders of political violence without an apology (M = 4.04, SE = 0.11, t = –13.59, p < 0.001, 95% CI: –0.788, –0.231) compared to the no reminder condition (M = 4.55, SE = 0.10), whereas these differences were only marginally significant between participants exposed to reminders with an apology (M = 2.30, SE = 0.10, t = 1.75, p = 0.082, 95% CI: –0.033 to 0.554) and those presented with reminders without an apology.

As regards the responsibility assignment to out-group (Spanish state), there was also a significant main effect of the experimental manipulation, F (2, 252) = 4.62, p = 0.011, η2 = 0.04. In this case, planned contrasts revealed that participants attributed less responsibility to out-group in the reminder without an apology condition (M = 3.95, SE = 0.09, t = –1.61, p = 0.082, 95% CI: –0.448 to 0.027) compared to the no reminder condition (M = 4.16, SE = 0.08), although this difference was only marginally significant. Yet, Sidak post hoc comparisons showed that responsibility assignment to out-group also decreased in the reminder with an apology condition (M = 3.79, SE = 0.09, p = 0.009) compared to the no reminder condition.

Together, reminders of political violence (not accompanied by an apology) activated lower responsibility attributions to ETA and Basque nationalism, yet also (marginally) lower responsibility assignment to police forces and the Spanish state, thus partially confirming H1a. In turn, reminders together with an apology activated lower assignment of responsibility to police forces and the Spanish state, but only compared to the no reminder condition, as well as higher responsibility assignment to ETA and Basque nationalism, also partially confirming the effectiveness of apologies (H1b).3.4 Effects of framing political violence on in-group victimhood perceptions

There was also a significant main effect of the experimental manipulation on in-group victimhood (F (2,253) = 7.28, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.05). As predicted by H1a, the perception of in-group victimhood significantly increased among participants exposed to reminders of political violence without an apology (M = 3.92, SE = 0.18, t = 3.82, p < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.460 to 1.440) compared to the no reminder condition (M = 2.97, SE = 0.17). In the reminder with an apology condition perceptions of in-group victimhood were significantly lower (M = 3.39, SE = 0.19, t = 2.00, p = 0.047, 95% CI: –1.041 to –0.008) compared to reminders without an apology. Thus, both H1a and H1b were confirmed, in this case.

3.5 Effects of framing political violence on intergroup revenge

Finally, we also found a significant effect of the experimental the manipulation on intergroup revenge, F (2,253) = 3.77, p = 0.024, η2 = 0.03. There was more desire for intergroup revenge among participants exposed to reminders of political violence without an apology (M = 1.76, SE = 0.12, t = 2.52, p = 0.013, 95% CI: 0.087, 0.722) as compared to the no reminder condition (M = 1.36, SE = 0.11), whereas participants presented with reminders accompanied with an apology (M = 1.70, SE = 0.12, t = –0.35, p = 0.728, 95% CI: –0.393 to 0.275) did not differ from those exposed to reminders without an apology. This result confirmed H1a but did not confirm H1b.

3.6 Indirect effects

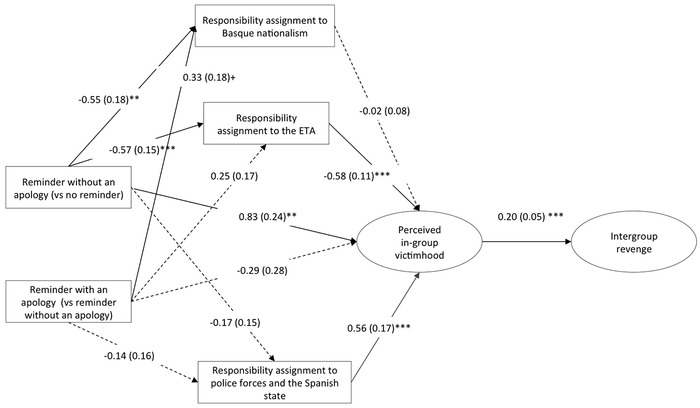

To test the remaining hypotheses, we estimated as SEM model (Figure 1) as described in the Analytical strategy section. This model showed a good fit to the data (χ2 (104) = 219.22, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05.

Figure 1: SEM model: the effects of reminders of political violence with and without an apology on intergroup revenge through responsibility attributions and perceived in-group victimhood. Path coefficients are unstandardised regression estimates. Standard errors are presented in parentheses; controlled for political orientation; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Model fit: χ2 (104) = 219.22, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05.

Corroborating H2a, the bootstrap analysis yielded a significant indirect effect of reminders of political violence without an apology (compared to no reminders) on intergroup revenge through increased perceived in-group victimhood (B = 0.17, SE = 0.07, p = 0.012, bootstrapped 99.5% CI: 0.058 to 0.280), whereas there was no significant indirect effect through in-group victimhood of reminders with an apology (B = –0.06, SE = 0.06, p = 0.322, bootstrapped 95% CI: –0.159 to 0.040), as compared to reminders without an apology (not confirming H2b).

Furthermore, partially in-line with H3a, there was a significant sequential indirect effect of reminders of political violence without an apology (compared to no reminders) on intergroup revenge through decreased responsibility attribution to ETA and thus strengthened perception of in-group victimhood (B = 0.07, SE = 0.03, p = 0.012, bootstrapped 95% CI: 0.024 to 0.113). In other words, reminders of political violence (without an apology) activated defensive responsibility attributions and thus more perception of in-group victimhood. This, in turn, led to more desire for intergroup revenge. Yet, no sequential indirect effects were found through responsibility attributions to Basque nationalism (B = 0.00, SE = 0.01, p = 0.837, bootstrapped 95% CI: –0.014 to 0.118) or to police forces and the Spanish state (B = –0.02, SE = 0.02, p = 0.299, bootstrapped 95% CI: –0.051 to 0.012).

Finally, the analyses did not reveal any significant sequential indirect effect of reminders of political violence with an apology (compared to reminders without an apology) on intergroup revenge through responsibility attributions and in-group victimhood (attributions to ETA and its environment: B = –0.03, SE = 0.02, p = 0.182, bootstrapped 95% CI: –0.068 to 0.007, to Basque nationalism: B = 0.00, SE = 0.01, p = 0.850, bootstrapped 95% CI: –0.012 to 0.009, and to police forces and the Spanish state: B = –0.02, SE = 0.02, p = 0.418, bootstrapped 95% CI: –0.050 to 0.017), not corroborating H3b. -

4. Discussion

This study examined the impact of reminders of political violence accompanied by an apology or not on intergroup dynamics in a post-conflict setting of the Basque Country. We found that a reminder of violent conflict incited a direct negative response in terms of higher desire for intergroup revenge, stronger perceptions of in-group victimhood and generally more defensive responsibility attributions. However, our study did not provide empirical evidence for the alleviating effects of institutional apologies, above the effects of reminders of political violence, in the Basque context.

4.1 How reminders of political violence fuel the conflict

The results showed that reminding people of political violence that the group experienced or perpetuated has inflammatory effect on the desire for revenge. These effects were obtained in spite of the fact that most victims mentioned in the experimental manipulation were the victims of ‘the fighters’ for independence of the Basque Country (in-group members). That is, the participants, in a vast majority strongly identified as Basques, were exposed to information that the transgression committed (even though indirectly) could be attributed to the in-group. However, simultaneously, the narrative of political violence in the present study was a reminder of suffering both in terms of the victims of ETA as well as the victims of state violence. Therefore, in one way or another, we found that reminders of past collective violence involving the in-group have detrimental effects for intergroup outcomes, confirming existing research on the effects of both in-group suffering (Noor et al., 2012; Rotella, Richeson, Chiao & Bean, 2013; Rouhana & Bar-Tal, 1998; Wohl & Branscombe, 2008) and in-group wrongdoings (Rotella et al., 2013). Our research expands previous studies by showing that the reminders of past collective violence also incite the desire for revenge.

Also, confirming the proposal of intergroup defensive or biased responses, reminders of past violent acts debilitated responsibility attributions to Basque nationalists and ETA and the environment, and provoked (although this effect was only marginally significant) more external attributions (i.e. responsibility assignment to police forces and the Spanish state). Further, as expected, reminders of past political violence increased perceptions of in-group victimhood. In addition, perceptions of in-group victimhood explained the effects of the narrative of political violence (compared to no reminder) on intergroup revenge, also in a sequential way, where a decreased responsibility attribution to ETA and the environment strengthened perception of in-group victimhood and thus intergroup revenge. Yet, responsibility assignment to the Spanish state did not explain sequentially (together with in-group victimhood) the effect of reminders of political violence on intergroup revenge, which may suggest that our participants rather represent the perpetrator group, for whom reminders of not only in-group suffering but also in-group transgression evoked more defensive responses with regard to the in-group responsibility rather than blaming the out-group (Spaniards) more. Further, this nuance also confirms that in the case of the conflict analysed in this study, these are rather within-group socio-psychological processes that are relevant explanatory mechanisms rather than blaming the out-group (Spanish state). Such findings reflect the complexity of within-group conflicts and within-group apologies, suggested in the introduction. Future research should also address possible shortcomings of this study and take into account participants’ identification with different agents responsible for political violence in this conflict.

Together, our results are in-line with previous research showing that groups tend to minimise own responsibility for intergroup transgressions (Branscombe & Miron, 2004) and that in-group victimhood narrative is linked to the denial of the ‘other’s’ narrative. Together, the collective remembering of violent acts ‘blinds’ people in their processing of information about past political violence and further nourishes the perceptions of in-group victimhood, thus legitimising negative out-group response.4.2 Limited effectiveness of institutional apologies

As for the apologies, the results provided limited evidence of their effectiveness. Being reminded of political violence along with the conciliatory acts offered by the Basque Parliament did not manage to reduce the desire for intergroup revenge compared to the political violence narrative. These results resonate with the existing debate over the effectiveness of intergroup or institutional apologies (Blatz et al., 2009; Blatz & Philpot, 2010; Blatz & Ross, 2012; Hornsey & Wohl, 2013; Hornsey et al., 2015 for reviews) and empirical evidence suggesting that in particular apologies for severe transgression are received with criticism and have limited effects (Ferguson et al., 2007; Philpot & Hornsey, 2011; Wohl et al., 2013). Previous research has failed to show the effectiveness of apologies particularly in promoting intergroup forgiveness (Philpot & Hornsey, 2011; Wohl et al., 2013). Our study expands previous lack of evidence for apologies to heal the wounds in the aftermath of severe transgression in terms of emotional outcomes, in our case, intergroup revenge. The analyses did not also provide evidence of indirect effects of institutional apologies on intergroup revenge.

The apologies presented by the Basque Parliament were also perceived as coming from a rather reliable source and credible, but these evaluations were just barely above the midpoint and with considerable standard deviations, thus suggesting that there is controversy rather than consensus on how the apologies were received. Previous research has shown the relevance of perceived sincerity for the effectiveness of apologies (Okimoto et al., 2015; Philpot & Hornsey, 2011; Shnabel et al., 2015; Staub, 2005; Wohl et al., 2012, 2013). Institutional apologies tend to be perceived as insincere particularly in the case of severe transgressions and/or the context of an intractable conflict (Shnabel, Halabi & SimanTov- Nachlieli, 2015), and for this reason they turned out to be ineffective in promoting intergroup reconciliation.

Another possible explanation is that existing research on apologies mostly focused on the victims. In our study, we could not clearly categorise our participants as either the victims or the perpetrators. We examined the effectiveness of apologies that come from the in-group to the victims of political violence among members of the in-group (Basques, mostly strongly identified as such). Future research should address these nuances. One possibility to examine the effectiveness of apologies among the victim category could be experimentally testing the effectiveness of fictitious (because never delivered) apologies by the Spanish government directed to the victims of state violence in the Basque Country.

Although the present study did not provide evidence of positive effects of apologetic acts on affect-loaded intergroup outcomes such as intergroup revenge, it does lend support to the hypothesised effects of institutional apologies on more cognitive intergroup outcomes. Institutional apologies deactivated defensive responsibility attributions, namely, led to lower assignment of responsibility to the Spanish state (but only compared to the control condition). That is, the apology delivered by the Basque Parliament reduced to some extent blame for the collective harm caused by Spanish nationalism, national police, Civil Guard, parapolice groups and extreme right wing, the agents representing the out-group in the Basque conflict. These findings are in-line with previous empirical research showing that after being exposed to information about intergroup apologies, the lower collective guilt assignment to the out-group, they were more willing to forgive the victims (Wohl et al., 2013). Finally, the apology facilitated the responsibility assignment to Basque nationalism. Such results support findings that collective guilt acceptance is associated with more positive intergroup relations among the perpetrator group (Wohl et al., 2013).

Globally, our findings only partially confirm that apologies help overcome defensive psychological responses whereas they do not serve to overcome certain emotional responses, in-line with previous empirical research demonstrating the limited effects of apologies for severe intergroup transgressions (Ferguson et al., 2007; Philpot & Hornsey, 2011; Wohl et al., 2013). Our findings reflect well the contemporary political reality in the Basque context. Once the disarmament of ETA became a reality, the demands for ETA to apologise for their transgressions became part of the public discourse. This perceived prescriptive norm may be a reason for Basque participants to react defensively towards an apology by the in-group representatives, confirming the effect of normative dilution (where the norms surrounding a behaviour devalue its symbolic worth) of apology’s power as demonstrated by Okimoto et al. (2015). However, it seems that institutional apologies in such contexts do help to reframe the narrative, allowing them to be assimilated and symbolically changed in order to achieve reconciliation. Reconciliation can be an emotionally painful process requiring time before it can promote forgiveness and positive emotional reactions towards the out-group. Basque conflict resolution is currently an on-going process and therefore reconciliation and forgiveness may require more time (Blatz & Philpot, 2010; Tavuchis, 1991). These findings support previous evidence demonstrating that the effects of intergroup apologies in the case of the Basque conflict are rather weak (Bobowik et al., 2010).4.3 Limitations

This study is not devoid of limitations. One drawback is that our conclusions are based on a single study and future replications are necessary to generalise the findings to other socio-political contexts where within-group apologies have taken place (e.g. South America). Another limitation of the present study is that we tested some causal effects and mediating processes but, given the cross-sectional nature of some part of the data, we cannot make any causal claim about the mediating paths and their order. For instance, it is also plausible to expect that reminders of political violence with or without an apology might impact perceptions of in-group victimhood, and in consequence, responsibility attributions. Further, we studied a real-life apology, with its own characteristics. Unfortunately, the apology is not explicitly specifying the type of victims of terrorism it is directed towards, and future research could use similar but to some extent fictitious apologies directed either to the victims of the ETA or to the victims of the Spanish state violence. In the case of such ‘blurred’ contexts, it would be also convenient to measure in future studies to what extent participants are identified with different ‘parties’ involved in the conflict. Finally, our experimental manipulation of an apology did not have substantial effects on intergroup dynamics or reconciliation outcomes. It is important to take into account that our manipulation has been subtle and thus might have had overall limited impact on participants.

4.4 Conclusion and practical implications

Framing past political violence has shown relevance for present-day intergroup relations in a post-conflict context. Importantly, in-group victimhood and responsibility attributions have been found to be mechanisms explaining the link between the type of reminders of the past (accompanied by an apology or not) and intergroup revenge. We have shown that narratives of political violence, when not accompanied by necessary initiatives of restorative justice, may further fuel the ‘cycle of victimhood’. Thus, our research sheds further light on the dangers of narratives of political violence if not properly framed. Even if these narratives reflect different types of victimisation, they seem to be processed selectively and further fuel narratives of victimhood and defensive responsibility attributions. Yet, institutional apologies such as the ones offered by the Basque Parliament may not be powerful enough to change perceptions of victimhood and responsibilities and thus shape responses towards the adversary. One of the reasons might be that they were not offered by the actual perpetrator or were not accompanied by other types of necessary reparations. Relevant political stakeholders, both in the Basque Country and also in other similar contexts, should take into account these possible limitations of restorative initiatives in order to effectively deal with the ‘demons from the past’ (Howard-Hassmann & Gibney, 2008).

References Bar-Tal, D. & Antebi, D. (1992). Beliefs about negative intentions of the world: a study of the Israeli siege mentality. Political Psychology, 13, 633-645. doi:10.2307/3791494.

Barkan, E. (2000). The guilt of nations: restitution and negotiating historical injustices. New York: Norton.

Basque Radio-Television EITB. (5 October 2007). Pleno sobre víctimas [Plenary session on victims]. Bilbao, Spain. Retrieved from www.eitb24.com/noticia/es/B24_69441.

Berndsen, M., Hornsey, M.J. & Wohl, M.J.A. (2015). The impact of a victim-focused apology on forgiveness in an intergroup context. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 18, 726-739. doi:10.1177/1368430215586275.

Bilali, R. (2012). Collective memories of intergroup conflict. In D.J. Christie (ed.), The encyclopedia of peace psychology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Blatz, C.W. & Philpot, C.R. (2010). On the outcomes of intergroup apologies: a review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 995-1007. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00318.x.

Blatz, C.W. & Ross, M. (2012). Apologies and forgiveness. In D.J. Christie (ed.), The encyclopedia of peace psychology (1st ed., pp. 43-47). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Blatz, C.W., Schumann, K. & Ross, M. (2009). Government apologies for historical injustices. Political Psychology, 30, 219-241. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00689.x.

Bobowik, M., Bilbao, M.A. & Momoitio, J. (2010). Psychosocial effects of forgiveness petition and ‘self-criticism’ by the Basque Government and Parliament directed to the victims of collective violence. Revista de Psicología Social, 25, 87-100. doi:10.1174/021347410790193478.

Bobowik, M., Páez, D., Arnoso, M., Cárdenas, M., Rimé, B., Zubieta, E. & Muratori, M. (2017). Institutional apologies and socio-emotional climate in the South American context. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56, 578-598. doi:10.1111/bjso.12200.

Branscombe, N.R. & Miron, A.M. (2004). Interpreting the in-group’s negative actions toward another group: emotional reactions to appraised harm. In L.Z. Tiedens & C.W. Leach (eds.), The social life of emotion (pp. 314-335). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, R.P., Wohl, M.J.A. & Exline, J.J. (2008). Taking up offenses: second hand forgiveness and group identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1406-1419. doi:10.1177/0146167208321538.

Carmena, M., Landa, J.M., Múgica, R. & Uriarte, J. (2013). Informe-base de vulneraciones de derechos humanos en el caso vasco (1960-2013). Gobierno Vasco: Vitoria-Gasteiz, Basque Government. Retrieved on May 15, 2013 from www.eskolabakegune.euskadi.net/web/eskolabakegune/informe-base-devulneraciones-de-derechos-humanos-en-el-caso-vasco-1960–2013.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S.G. & Aiken, L.S. (2003). Applied multiple regression and correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Davis, M.J. (2010). Contrast coding in multiple regression analysis: strengths, weaknesses, and utility of popular coding structures. Journal of Data Science, 8, 61-73. doi:10.6339/JDS.2010.08(1).563.

Espiau, G. (2006, April). The Basque conflict. New ideas and prospects for peace. Special report. Washington D.C.: US Institute of Peace. Retrieved on May 15, 2013 from https://www.usip.org/publications/2006/04/basque-conflict-new-ideas-and-prospects-peace.

Euskobarometer. (2011). Estudio periódico de la opinión pública vasca [Periodic study of the Basque public opinión]. San Sebastián: Universidad del País Vasco. Retrieved on May 15, 2013 from www.ehu.es/documents/1457190/1525260/EB1111.pdf.

Eustat. (2011). Statistical tables of population. Municipal statistics of inhabitants 2011. Retrieved on May 15, 2013 from www.eustat.es.

Ferguson, N., Binks, E., Roe, M.D., Brown, J.N., Adams, T., Cruise, S.M. & Lewis, C.A. (2007). The IRA apology of 2002 and forgiveness in Northern Ireland’s Troubles: a cross-national study of printed media. Peace & Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 13, 93-113. doi:10.1037/h0094026.

Gerber, M. & Jackson, J. (2013). Retribution as revenge and retribution as just deserts. Social Justice Research, 26, 61-80. doi:10.1007/s11211-012-0174-7.

Gibson, J.L. (2004). Overcoming Apartheid: can truth reconcile a divided nation? New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hayes, A.F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A.F. & Preacher, K.J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67, 451-470.

Hornsey, M.J. & Wohl, M.J.A. (2013). We are sorry: intergroup apologies and their tenuous link with intergroup forgiveness. European Review of Social Psychology, 24, 1-31. doi:10.1080/10463283.2013.822206.

Hornsey M.J., Wohl, M.J.A., & Philpot, C.R. (2015). Collective apologies and their effects on forgiveness: Pessimistic evidence but constructive implications. Australian Psychologist, 50, 106–114. doi:10.1111/ap.12087.

Howard-Hassmann, R.E. & Gibney, M. (2008). Introduction: apologies and the West. In M. Gibney & R.E. Howard-Hassmann (eds.), The age of apology: facing up to the past (pp. 1-12). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Hu, L. & Bentler, P.M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424/.

Lastrego, S. & Licata, L. (2010). ‘Should a country’s leaders apologize for its past misdeeds?’ An analysis of the effects of both public apologies from a Belgian official and perception of Congolese victims’ continued suffering. Revista de Psicología Social, 25, 61-72. doi:10.1174/021347410790193432.

Leonard, D.J., Mackie, D.M. & Smith, E.R. (2011). Emotional responses to intergroup apology mediate intergroup forgiveness and retribution. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1198-1206. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.002.

Lickel, B., Miller, N., Stenstrom, D.M., Denson, T.F. & Schmader, T. (2006). Vicarious retribution: the role of collective blame in intergroup aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 372-390. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_6.

Marrus, M.R. (2006). Official apologies and the quest for historical justice (Occasional Paper, no. 111). Toronto: Munk Centre for International Studies.

Martín-Peña, J. & Opotow, S. (2011). The legitimization of political violence: a case study of ETA in the Basque Country. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 17, 132-150. doi:10.1080/10781919.2010.550225.

McCullough, M.E., Rachal, K.C., Sandage, S.J., Worthington, E.L., Jr., Brown, S.W. & Hight, T.L. (1998). Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1586-1603. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.6.1586.

McGarty, C., Pedersen, A., Leach, C.W., Mansell, T., Waller, J. & Bliuc, A.M. (2005). Group-based guilt as a predictor of commitment to apology. British Journal of Social Psychology, 44, 659-680. doi:10.1348/014466604X18974.

Muthén, L.K. & Muthén, B.O. (2010). MPLUS (version 6). Los Angeles, CA: Author.

Nadler, A., & Liviatan, I. (2006). Intergroup Reconciliation: Effects of Adversary Expressions of Empathy, Responsibility, and Recipients’ Trust. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 459–470. doi:10.1177/0146167205276431.

Noor, M., Shnabel, N., Halabi, S. & Nadler, A. (2012). When suffering begets suffering: the psychology of competitive victimhood between adversarial groups in violent conflicts. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16, 351-374. doi:10.1177/1088868312440048.

Okimoto, T.G., Wenzel, M., & Hornsey, M.J. (2015). Apologies demanded yet devalued: Normative dilution in the age of apology. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 60, 133–136. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2015.05.008.

Páez, D. (2010). Official or political apologies and improvement of intergroup relations. Revista de Psicología Social, 25, 101-115. doi:10.1174/021347410790193504.

Philpot, C.R., Balvin, N., Mellor D., & Bretherton, D. (2013). Making meaning from collective apologies: The case of Australia’s apology to its Indigenous peoples. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 19, 34–50. doi:10.1037/a0031267.

Philpot, C.R. & Hornsey M.J. (2008). What happens when groups say sorry: the effect of intergroup apologies on their recipients. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 474-487. doi:10.1177/0146167207311283.

Philpot, C.R. & Hornsey M.J. (2011). Collective memory for apology and its relationship with forgiveness. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 96-106. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511619168.006.

Rotella, K.N., Richeson, J.A., Chiao, J.Y. & Bean, M.G. (2013). Blinding trust: the effect of perceived group victimization on intergroup trust. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 115-127. doi:10.1177/0146167212466114.

Rouhana, N.N. & Bar-Tal, D. (1998). Psychological dynamics of intractable ethnonational conflicts: the Israeli-Palestinian case. American Psychologist, 53, 761-770. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.7.761.

Salomon, G. (2004). A narrative-based view of coexistence education. Journal of Social Issues, 60, 273-288. doi:10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00118.x.

Schori-Eyal, N., Klar, Y., Roccas, S. & McNeill, N. (2017). The shadows of the past: effects of historical group trauma on current intergroup conflicts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43, 538-554. doi:10.1177/0146167216689063.

Shnabel, N., Halabi, S., & SimanTov- Nachlieli, I. (2015). Group apology under unstable status relations: Perceptions of insincerity hinder reconciliation and forgiveness. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 18, 716–725. doi:10.1177/1368430214546069.

Shnabel, N., & Nadler, A. (2008). A needs-based model of reconciliation: Satisfying the differential emotional needs of victim and perpetrator as a key to promoting reconciliation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 116–132. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.116.

Simantov-Nachlieli, I.S. & Shnabel, N. (2014). Feeling both victim and perpetrator: investigating duality within the needs-based model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 301-314. doi:10.1177/0146167213510746.

Staub, I. (2005). Constructive rather than harmful forgiveness, reconciliation, and ways to promote them after genocide and mass killing. In E. L. Worthington (Ed.), Handbook of forgiveness (pp. 443–459). New York: Routledge.

Steele, R.R. & Blatz, C.W. (2014). Faith in the just behavior of others: intergroup apologies and apology elaboration. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 2, 268-288. doi:10.5964/jspp.v2i1.404.

Tavuchis, N. (1991). Mea Culpa: a sociology of apology and reconciliation. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

The Basque Parliament. (5 October 2007). The analysis and discussion of compliance with the resolutions adopted on victims of terrorism and adoption of relevant resolutions. Resolution Nr 1. (Nr. 69). Plenary session on the victims of terrorism. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Author. Retrieved from www.parlamento.euskadi.net/pdfdocs/publi/2/08/000069.pdf#1 (last accessed 15 May 2013).

Valencia, J., Momoitio, J. & Idoyaga, N. (2010). Social representations and memory: the psychosocial impact of the Spanish ‘Law of Memory’, related to the Spanish Civil War. Revista de Psicología Social, 24, 73-86. doi:10.1174/021347410790193496.

Varela-Rey, A., Rodríguez-Caballeira, A. & Martín-Peña, J. (2013). Psychosocial analysis of ETA’s violence legitimation discourse. Revista de Psicología Social, 28, 85-98. doi:10.1174/021347413804756050.

Vollhardt, J.K. (2009). The role of victim beliefs in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: risk or potential for peace? Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 15, 135-159. doi:10.1080/10781910802544373.

Von Hirsch, A. (1976). Doing justice: the choice of punishments. Report of the Committee for the Study of Incarceration. New York: Hill and Wang.

Wohl, M.J.A. & Branscombe, N.R. (2008). Remembering historical victimization: collective guilt for current in-group transgressions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 988-1006. doi:10.1037/0022- 3514.88.2.288.

Wohl, M.J.A., Hornsey, M.J. & Bennett, S.H. (2012). Why group apologies succeed and fail: intergroup forgiveness and the role of primary and secondary emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 306-322. doi:10.1037/a0024838.

Wohl, M.J.A., Hornsey, M.J. & Philpot, C.R. (2011). A critical review of official public apologies: aims, pitfalls, and a staircase model of effectiveness. Social Issues and Policy Review, 5, 70-100. doi:10.1111/j.1751-2409.2011.01026.x.

Wohl, M.J.A., Matheson, K., Branscombe, N.R. & Anisman, H. (2013). Victim and perpetrator groups’ responses to the Canadian government’s apology for the head tax on Chinese immigrants and the moderating influence of collective guilt. Political Psychology, 34, 713-729. doi:10.1111/pops.12017.

Appendix 1 -

Reminder of political violence

One of the effects of political conflict in the recent history of the Basque Country has been the political violence and its consequences. In particular, the political conflict in the Basque Country after the Civil War is linked to the following characteristics: duration of about 40 years (1968-2010), 1,100 people killed, 6,000 people injured, and 6,000 subjected to abuse or torture by the police. A recent research has found that 1.5 per cent of the Basque population is affected by the deaths or injuries caused by political violence. Seven per cent claimed to be a victim of blackmail, attacks, social isolation and ostracism for political reasons. It is estimated that 25,000 people (1 per cent of the population) are involved in arrests and trials related to the radical left. The numbers of political violence could be summarised as follows: 836 deaths caused by ETA and similar groups mainly in the 1980s; 76 militants of the ETA killed in action; 34 protesters killed by police; 42 people killed during police controls mainly before 1982; 42 people killed by vigilante groups and counterterrorism apparatus of the State between 1975 and 1982 and 28 killed between 1983 and 1987.

-

Apology

Moreover, recently the Basque Parliament, in a monographic plenary session of 2007, has achieved a broad consensus and made an act of asking the victims of the conflict for forgiveness. It urges the Basque Government to fulfil the agreements on victims. Basque parliamentary parties agreed on twenty resolutions concerning reparations for victims of terrorism, in which, first, the parliamentarians ‘solemnly and publicly asked the victims to forgive the neglect and abandonment they have felt and suffered for too many years’. The following recommendation is of special importance:

It is recommended that the Basque institutions, in an appropriate extent corresponding to each of them, and the society in general promote and actively participate in the initiatives of the tribute and moral, social and political appreciation directed to the victims of terrorism.

In addition, the editorial of a Basque representative newspaper commented this law as follows:

Basque society will have the opportunity to show their solidarity and closeness to the victims of terrorism through an act of justice that seeks to repair the moral debt that the Basque society and institutions have with the victims. We are witnessing an act of homage and recognition, but it is much more than that. It is a demonstration of forgiveness. Forgiveness for not being close to the victims of ETA, for not supporting them, for forgetting or avoiding, for not giving them the recognition they deserve, or at least, for not knowing how to express it. The confrontation and the conflict continue to prevent unanimity in a case in which what should take precedence over all is recognition of the pain of someone else.

Furthermore, on 29 September 2011, lehendakari Patxi López declared:

And there have been practices that, abandoning the rule of law, sought to end the terrorism of ETA with other terrorism, as the Spanish-Basque Battalion (GAL) that belongs to the past but is present in the memory of its victims. The illegal and anti-democratic acts executed by public officials have been particularly perverse because they were acting on behalf of the rule of law and weakening the arguments of defenders of democracy. I want to recognize again the truth of what happened and to condemn again those acts in order to legitimize our current democratic system, which, time ago, managed to overcome and eradicate the evils of the past.

‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’

George Santayana