-

1 Introduction

In representative democracy, citizen participation is theoretically confined to election and public debate. However, in practice, a certain number of established democracies provide also alternative policy instruments allowing lay citizens to influence the decision-making process. Mechanisms of ‘direct democracy’ like referendums have thus become increasingly popular in Europe among the public opinion but also among policymakers, as the growing use since the end of the twentieth and over the beginning of the twenty-first century suggests (Qvortrup 2018). This shift constitutes a significant institutional evolution in the conduct of public action in many established democracies, which aims at giving more space to citizens through direct participation, as a complement to their representation.

According to ‘cognitive mobilisation theories’, the progress in resources’ access via higher education and better communication technology would have made citizens better equipped to participate in politics and more demanding of opportunities of involvement beyond election. The latter view is nonetheless challenged by the ‘political dissatisfaction hypothesis’ that claims that the increasing demand and offer in referendums reflects a willingness of the representative institutions to respond to the disaffection towards traditional political bodies rampant among the citizens. Moreover, recent cases of referendums (like on Brexit in the United Kingdom) have raised concerns about the eventual backlashing impact of the use of direct democracy. One fear relates to the instrumentalisation of these policy tools by radical forces to avoid legislatures and impose their populist agenda. From recent studies, we learned that an important line of demarcation when we approached referendums from either the supply or the demand side is driven by the role of ideology. Parties and voters’ support for referendums align not only with the classical left-right distinction but also with a split between radical (anti-establishment) and mainstream party families.

Although much has been written on direct democracy in recent years, the positioning of the parties and the voters on the question remains less empirically explored (at the same time), and especially in the framework of Benelux countries that are known for a very low occurrence of referendums (Hollander 2019). We still know little about (1) whether existing individual-level, ideology-driven explanations for referendum support could hold when zooming on these three countries, (2) whether and how (both radical and mainstream) voters and parties align on their view regarding the use of direct democracy. Therefore, this article aims at disentangling more carefully the relationship of ideology with support for referendums among both the voters and their parties. To do so, we rely on the analysis of individual-level survey data gathered among three representative samples of voters in Luxembourg, Belgium and the Netherlands, for the demand side, while party-level data provided by electoral manifesto and official sources are used to match with the supply side. -

2 Literature Review

2.1 Support for Referendums among Voters

The literature on direct democracy has been growing increasingly bigger since the early 2000s. If studies on direct democracy existed before, an important focus on the demand side both from voters and elites has been made. Following a valuable amount of works that pointed out the increasing popularity of referendum among citizens (e.g., Dalton et al. 2001; Morel 2019; Hollander 2019), Bowler et al. (2007) studied this support in 12 Western countries. They showed that a vast majority of respondents are favourable to the implementation of referendums. Between 55 and 84 per cent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that referendums are a good way to decide important political questions. Schuck and de Vreese (2015) emphasise this increasing popularity of referendums among voters but introduced more nuanced views. On one side, they showed that referendums are also increasingly contested; on the other hand, they identified different, and somehow conflicted, factors that determine this contestation. In a more recent work based on a sample of more than 37,000 citizens from 29 countries, Werner and her colleagues (Werner et al. 2020) acknowledged also a significant level support for referendums among European citizens, with a mean score of 8.27 on a 0-10 points scale. Yet, some evidence at the individual-level stresses that this support may be greatly instrumental and conditioned by perceiving positive outcomes (Brummel 2020; Werner 2020).

In their work, Bowler et al. (2007) found that two subgroups in the population envision more favourably direct democracy: the ‘politically engaged’ and the ‘politically dissatisfied’. On the one hand, ‘engaged citizens’ are characterised by their greater cognitive resources. They are more educated, have more knowledge and are more interested in politics and hence motivated to participate directly in politics (Schuck and de Vreese 2015). Moreover, they feel competent and consider that they have the skills to participate. They are no longer content with only voting for elections and want more opportunities to participate. This cognitive mobilisation explanation is related to the post-materialism turn described by authors such as Inglehart (1971). Yet, if most studies point towards a positive effect of political engagement on support for direct democracy and citizen participation, there are also some works contradicting these findings. Rojon and Rijken (2020) demonstrated in a study on Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Hungary that although citizens’ support for referendums is still important, ‘winners of modernisation’ with higher education and revenues tend to become less favourable to referendums (Rojon and Rijken 2020). One trend of explanation is the outcome of recent referendums in European countries (e.g., Brexit). In particular, the defeat of the democratic ‘status quo’ may have refrained the support from this group of citizens (Hobolt 2016). Another one is, as shown in more recent works, that more educated and socio-economically advantaged citizens favour more deliberative ways of engaging in politics (Pilet et al. 2020). A last potential reason is advanced by Anderson and Goodyear-Grant (2010) in their work on Canada: highly informed citizens were more sceptical of referendums because they cared about minority rights. In contrast, less knowledgeable citizens may not perceive that referendums, as majoritarian instruments, can reinforce the dominance of the majority and jeopardise minorities’ rights.

On the other hand, the ‘dissatisfied’ group gathers citizens who are not content with the way democracy works. Their disaffection is thus rooted in a low level of trust in government and representative democracy (Bowler et al. 2007; Cain et al. 2003), which lead them to be more supportive of alternatives to voice citizens in the political process and hence more favourable to direct democracy (Webb 2013). Similarly, reflecting this disenchantment, citizens who feel disconnected from traditional party politics and are at the margins of the political process generally express preferences for referendums (Schuck and de Vreese 2015). Yet, more than a call for more participation, support for direct democracy in this group is also a matter of a perceived lack of responsiveness of the government with the public opinion (Werner et al. 2020). In a study on the Yellow Vests’ democratic aspiration, Abrial and her colleagues (2022) found out that the ones who have a monolithic view of political class, primarily first-time activists, see favourably direct forms of participation not so much to participate, but more to control and sanction political parties and elites. This suggests that Webb’s findings about two types of attitudes prevalent among disaffected citizens are relevant. According to him, there is a split between ‘dissatisfied democratic’ and ‘stealth democratic’ orientations in the British adult population. Dissatisfied democrats are enthusiasts for all form of participation while stealth democrats are more into referendums as a means to bypass politicians (Mudde 2004; Rooduijn 2014; Rooduijn et al. 2016; Van Hauwaert and Van Kesse 2018; Webb 2013; Zaslove et al. 2021).

Besides the level of socio-political resources and the attitudes towards representative democracy and its main actors and institutions, a last important aspect to comprehend citizens’ attitudes towards referendum relates to ideological and partisan preferences. Although it seems to be particularly confined, empirically speaking, to Western Europe (Kostelka and Rovny 2019), it has been long and repeatedly theorised that individuals leaning on the left have greater chances to engage in participatory behaviours (Barnes and Kaase 1979; Bernhagen and Marsh 2007; Torcal et al. 2016; van der Meer et al. 2009). This would be because these people are attached to core values promoted by left movements and parties since the 1960s (Kitschelt 1988), e.g., collective engagement and bargaining, equality or still inclusion. More largely, although scholars do not all agree on the relevant justification, they put forward three potential explanations for this association (Kostelka and Rovny 2019). The first explanation is economic. The support for redistributive policies and state intervention in the economy that characterises left-wing voters (and parties) could push them to be more prone to adopt participatory behaviours in order to fight against socio-economic inequalities. The second explanation is cultural. Indeed, cultural liberalism, egalitarian views, and the rejection of traditional social hierarchy (which are generally associated with the left) generally make people more likely to undertake participatory actions. Klingemann (1979) stressed that those left-wing, postmaterialist people who advocate greater equality were more willing to adopt new means of participation, whereas the right-wing, materialist people (who care less about social equality) were more supportive of the status quo. Third and final, since the very beginning of mass politics, the left is historically associated with the use of protest forms of participation in their fight for political and social rights of the working class. Hence, claiming more citizen participation has been above all perceived as a territory of the left.

Although the literature questioning the link between ideological preferences and political participation of all kinds is well developed, while the one connecting ideology and vote choice is abundant, the impact on democratic preferences remains much less substantial (Ceka and Magalhães 2016; Jurado and Navarrete 2021). That is the reason why, inspired by the above-mentioned argument of an affinity between citizens’ participation and left-wing values, some scholars have brought in the idea that the support for the enlargement of participatory opportunities and the use of policy instruments that would give a greater role to citizens in decision-making might be driven by where people stand on the left/right cleavage. They stressed that citizens who place themselves on the left of the left-right scale are generally more likely to support increased participation in decision-making (Walsh and Elkink 2021), while, more precisely, opinions about referendums are usually more positive among left-wing than right-wing individuals (Fernández Martínez and Font Fábregas 2018; Rojon et al. 2019; Webb 2013). Christensen and Von Schoultz (2019) found indeed that citizens sharing leftist/cosmopolitan values tend to favour participatory political processes, while Bengtsson and Mattila (2009) demonstrated that identification with the left increased the likelihood of supporting the use of referendums.

However, similar to the literature on citizens’ preferences for democracy (König et al. 2022), the empirical results remain fragmented and are not always consistent when it comes to the ideological roots of referendum support. Somehow connected to the dissatisfied thesis, what recent studies have observed is instead a strong cleavage based on radical and moderate party preferences, between people voting for radical parties and those moderate voters opting for mainstream parties embedded in traditional left or right ideologies (Paulis and Ognibene 2022). People casting vote in favour of parties located at the extreme, both on the right and left sides of the political spectrum, are more favourable to referendums (Rojon and Rijken 2020; Schuck and de Vreese 2015). As an illustration of this trend in France, in 2017, 75 per cent of supporters of the left-wing party La France Insoumise and 79 per cent of supporters of the radical-right party Rassemblement National were in favour of referendums while this support was between 60 and 49 per cent among supporters of more mainstream parties (Morel 2019). To explain it, besides the high level of dissatisfaction (Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel 2018), one central factor lies in the common populist attitudes adopted by both radical left and right-party voters. Those individuals are generally more critical of institutions such as political parties (Zaslove et al. 2021), consistent with the ‘anti-elitism’ identified as a subdimension of populism (Mudde 2004), and hence are more supportive of democratic reforms (Koch et al. 2021; van Dijk et al. 2020). Moreover, another, widely shared characteristic among populists is their ‘people-centrism’ and their demand for more people power in politics (Neuner and Wratil 2022). This predisposition is argued to make them highly predisposed to support the direct form of democracy (Jacobs et al. 2018).2.2 Support for Referendums among the Parties (and the Representatives)

First and foremost, it is important to point out that the literature on the side of the parties (and their representatives) suffers from two main limitations. First, very few individual-level studies were held on MPs’ attitudes towards referendums, while we lack meso-level contributions that would be informative on the role played by parties and their ideological preferences regarding democratic processes’ issues like the use of referendums (Font and Rico Motos 2023). Instead, existing pieces in party research have rather looked at the way parties mobilise (in) referendums or eventually seek to influence citizens’ choices and hence the results (Hobolt 2006; Gherghina and Silagadze 2021; Nemčok et al. 2019). Second, studies on the subject often focus indistinctively on both participatory and direct reforms of representative democracy. However, some key findings emerge from the literature.

A first important determinant to understand parties and elites’ positive stance towards referendums is the instrumental, or strategic aspect. It means that MPs and parties in the opposition, who lost an election or fear to lose one or have little or no power in the parliament view more favourably democratic reforms such as referendums (Bowler et al. 2002/2006; Junius et al. 2020). In contrast, parties that (are used to) win elections and are (highly) institutionalised have less incentives to implement disruptive tools that would change the status quo and eventually challenge their majority position. Yet, party organisational research has indicated that, when moderate, institutionalised parties suffer from several defeats or internal crises, they generally turn more favourable to changing the internal status quo and reforming their intra-party democracy by including more tools of direct participation in their organisation (Bloquet et al. 2022; Scarrow 2017). Moreover, in some context, parties can hijack direct democracy and promote the use of referendums as an electoral strategy that serves legitimacy purposes or intends to increase their popularity (Gherghina 2019; Stoychev and Tomova 2019). More largely, studies have acknowledged that ‘politicians and political parties may use referendums in an attempt to solve internal disputes, advance the legislative agenda, gain legitimacy for fundamental changes, or extend their public electoral support’ (Gherghina 2019: 5).

A second determinant relates to the extreme or moderate nature of the ideology supported by the party and the MPs. Indeed, reflecting the division observed among the voters, radical anti-establishment parties and representatives are more positive about referendums than mainstream and traditional parties (Junius et al. 2020; Núñez et al. 2016). Like the voters, one individual-level line of explanation relates to the radical MPs’ dissatisfaction with how democracy works. The most dissatisfied MPs are generally those more favourable to referendums (Bowler et al. 2006; Niessen 2019). Furthermore, anti-establishment parties are found to be more enthusiastic about constraining referendums than other parties (Pascolo 2020) and rely more on direct democracy for their intra-party organisation (Gerbaudo 2021). This would be a consequence of their populist strategy and discourses, which binarise a critique of democracy opposing the people to all the devil elites and call to retrocede power in politics back to ordinary citizens. Our knowledge on this aspect has improved in recent years, thanks to the development of the study of parties’ electoral manifesto in one or several European countries (Brummel 2020; Pascolo 2020; Gherghina and Pilet 2021). Gherghina and Pilet (2021) show for instance that, although references to referendums were more common in the programs of populist parties, both populist and non-populist parties were supportive of a greater use of the tool, nuancing the idea that radical parties would have the main grip on the promotion of direct democratic tools. More recently, in a study on the implementation of participatory institutions in Spanish municipalities, Font and Rico Motos (2023) found that radical left-wing parties are more likely to use more direct forms of participation (such as participatory budgeting) than Christian democrats and conservatives. For these authors, one important aspect is thus the link between party ideology and the model of democracy it promotes. Radical left parties would be in favour of more non-mediated forms of direct democracy to ‘re-launch democracy on a participatory, anti-elitist and antiliberal basis’ (March and Mudde 2005) while centre-right liberal and Christian democrats are more into participatory institutions that do not challenge a more traditional electoral mechanisms. Social democratic parties are depicted as being in-between those positions, perceiving direct democracy as a good complementary strategy (Font and Rico Motos 2023). -

3 Hypotheses

3.1 Hypothesis 1. Left versus Right Preferences

Based on the supposed affinity between the left and citizen participation, referendums, as main policy instrument of direct democracy, are expected to be more positively evaluated by left-wing than right-wing citizens. The previous section has indeed acknowledged that there seems to exist a correlation between ideological positions and support for direct democracy, whatever these ideological preferences are operationalised through subjective (e.g., left-right self-placement) or more objective (e.g., positioning on socio-economic or cultural cleavages) measurements. Against this backdrop, our first expectation is that citizens leaning to the left of the political spectrum will be more supportive of the use of referendums. Moreover, as we know for long that there is also a strong association between ideological preferences and vote choice (Campbell et al. 1960; Quinn et al. 1999), we can also expect that the same relationship will be found when looking at left-wing party preferences. Citizens voting for parties that are generally ranged under the label of the ‘left’ (e.g., social democratic, green, or left libertarian) are expected to be more positive about the use of referendums.

H1: Compared to right-wing, citizens leaning on the left or voting for left-wing parties will support more the use of referendums.

3.2 Hypothesis 2. Radical versus Moderate Preferences

Yet, more recent findings have challenged this assumption about a left-right divide driving the support for direct democracy among the voters. Instead, it would be more a cleavage between extreme and moderate types of voters. The literature has argued that people who tend to place themselves on the extreme poles of the political spectrum or who vote for radical parties are generally more supportive of referendums than moderate voters.

H2: Compared to moderate voters, voters who locate themselves on the extreme poles of the left-right political space or vote for radical parties will support more the use of referendums.

3.3 Hypothesis 3. Left-Right Preferences among the Radical Voters

Existing studies did not find any statistical difference in the level of support depending on whether the radical voters cast their vote for far left or far right parties (Grotz and Lewandowsky 2020; Rojon et al. 2020; Svensson 2018; Van Dijk et al. 2020). Their support would indeed be more driven by their common populist attitudes, anti-elitist stance, and a need for control over corrupted politicians. This means that we cannot expect left or right orientation to drive the support for referendums among the radical voters, as both radical left- and right-party voters should have a relatively similar level of agreement on the use of referendums. Moreover, some scholars have argued and shown that citizens with more ideological extremeness are more supportive of referendums (Schuck and de Vreese 2015). This propensity towards direct democracy was observed both among citizens at the extreme left and the extreme right of the ideological self-placement (Donovan and Karp 2006) and among citizens with strong populist attitudes (Mohrenberg et al. 2021; Zaslove et al. 2021). We thus expect to observe a similar pattern than extreme left-right self-placement than with party preferences.

H3: Citizens positioned on the extreme left or voting for radical left parties will support the use of referendums as much as those positioned on extreme right or voting for radical right parties.

3.4 Hypothesis 4. Left-Right Party Preferences among Moderate Voters

Yet, we argue that the left-right divide may start to matter when zooming on the group of moderate voters because it gathers a large group of people with very heterogeneous party preferences and where parties embedded in traditional cleavages are supported. Here, being/voting on the left or on the right of the spectrum might potentially make a difference regarding direct democracy support. Interestingly, the democratic demands of these moderate voters and how ideology may shape the latter has been much less studied than their radical counterparts.

H4: Among moderate voters, citizens leaning on the left or voting for left-wing parties will support the use of referendums more than citizens leaning or voting for the right.

3.5 Hypothesis 5. Radical versus Moderate Party-Voter Congruence

Finally, we still know little about the proximity between voters and parties on the use of referendums, existing research focusing either on one or the other aspect. Therefore, the fifth general hypothesis focuses more specifically on the relationship between ideology and party-voter alignment. As we know that radical parties and voters are both the most supportive of direct democracy and that the literature on issue congruence informs us that voter-party proximity tends to be higher on issues that the party emphasises (Costello et al. 2021), we expect to observe that radical ideologies will be more capable than mainstream ones to generate consensus both on the supply (party) and the demand side (voters) regarding the use of referendum. This could mean that radical parties are potentially more responsive to the (direct) democratic demands of their voters, while pointing towards some resistance on the side of the moderate.

H5: Radical parties and voters will have more congruent, positive opinions on the use of referendums than their moderate counterparts.

3.6 Hypothesis 6. Party-Voter Congruence among the Moderate

Yet, as a corollary of the left-wing divide hypothesised among the moderate party voters (H4) and following our previous arguments, we expect to find more congruence on the left side of the mainstream political space when looking more closely at the moderate. Following our overall argument, moderate left-wing ideologies are expected to convey more agreement on the use of referendums between voters and their parties than right-wing ones.

H6: Among the mainstream, left parties and voters will have more congruent, positive opinions on the use of referendums than their right-wing counterparts.

-

4 Data and Methods

4.1 Cases: Benelux Countries

Besides having common features inherited from the past (e.g., parliamentary monarchies), another similarity that Benelux countries share is that they have been relatively spared by the turn towards direct democracy that other European countries have faced since the 1990s (see Appendix 11x For the Appendices referred to in this article, please see https://www.elevenjournals.com/tijdschrift/PLC/2023/1/PLC-D-22-00019A. for a European comparison). Belgium had only one referendum held in 1950 to vote about the return of King Leopold III after the Second World War. Referendums have more recently been used in the Netherlands and Luxembourg, although it was only twice (way below the European average) and advisory. If Luxembourg and the Netherlands provide referendum mechanisms in their respective constitutions, it is not the case for Belgium where no formal right is enshrined (see Appendix 2). This specific feature of Benelux countries makes them particularly interesting cases to study whether and how voters and parties position themselves towards direct democracy, as their judgements are not biased by previous national experiences and their outcomes. Moreover, they might be also good cases to assess the drivers of resistance. At a more general level, it is worth noting that Luxembourg has attracted so far less scholarly attention regarding parties and voters’ democratic preferences compared with Belgium or the Netherlands.

In addition, we think that they are relevant contexts to better explore the ideological roots of voters and parties’ support for referendums. This common background across the three countries may probably be explained by a similar political landscape: consensual dynamic in party politics, strongly dominated by traditional parties embedded in mainstream collective ideologies. The historical grip of three party families (namely the social democrats, the Christian democrats, and the liberals) on power and societies may potentially explain why these countries did not rely more on referendums. The mechanism might indeed have challenged their hegemonic position, despite voters expressing majority preferences for their implementation. This could turn into a gap between an increasing demand among the voters, but a very limited offer on the side of the parties. Moreover, stressing the increasing distrust towards traditional parties but also the loss of salience of historical cleavages, the dominance of ‘pilar’ parties has started to crumble over the last decades under the increasing electoral success of radical parties, on the right in Flanders (BE) and the Netherlands and on the left in Wallonia (BE) and Luxembourg, which are in fact the main promoter of the use of referendums in these countries. This evolution could eventually lead these countries and their ruling parties to reconsider their position regarding the place that should be given to direct democracy in the future.4.2 Data

Individual-level data (demand side). Data was collected through a CAWI survey fielded during winter 2022 in Belgium and the Netherlands (Qualtrics as provider) and during summer 2022 in Luxembourg (Ilres as provider).2x Please note that the data used in this article were collected in the framework of a larger project studying non-elected forms of democracy in Europe (ERC-funded project Cure Or Curse, grant agreement No 772695, politicize.eu), and a research convention (U-AGR-8113-00-C) on the Luxembourg Climate Citizens’ Assembly established between the University of Luxembourg and the Luxembourg government. In each country, a stratified sampling strategy ensured sufficient representation of persons from different socio-demographic groups based on four key characteristics: region of residence, age, sex and education.3x For Luxembourg, the education quota was difficult to implement on the side of the survey company. Instead, they used also professional activity and citizenship, given the singularity of the Luxembourg population (high proportion of residing non-nationals). Luxembourg’s responses are also weighed on these aspects. We can see from the distribution table provided in Appendix 3 that this does not prevent some groups from being over-represented in our samples (mostly older and better educated for the three countries, while Flemish citizens are more present in the Belgian sample). Therefore, after we merged the raw data, each country’s sample was weighted to match the distributions on these socio-demographic characteristics in the general population. The pooled sample includes 6,688 respondents, after excluding trackers, speeders and inattentive respondents who accounted for less than 2.7 per cent of the raw data. National sample size varies from 1,602 respondents for the Netherlands to 2,836 for Belgium and 2,250 for Luxembourg.4x The difference in size is mainly due to fieldwork circumstances and survey companies’ recruiting capacity. We initially contracted for a representative sample of (at least) 1,500 respondents in each country but agreed for larger sample if data quality was ensured.

Party-level data (supply side). For the survey respondents who voted in the last national elections of their country (2021 in the Netherlands, 2019 in Belgium, 2018 in Luxembourg), our dataset was complemented with different information on the supply side regarding the party they expressed their preference for. We considered all the parties that were running in the last national election cycle, even if they did not pass the threshold for representation (N = 42). The exact list of parties and their ideological classification is displayed in Table 1. Besides basic data on the party ideology, we collected party age (based on party origins), national parliamentary size (% of seats before the election) and incumbency (whether the party was in government before the election) from official sources and available databases. The electoral manifesto provided on the official website of the parties was used to measure their stance on the use of referendums (see Appendix 5. Coding of the electoral manifesto).

Table 1 List of the parties/voters coveredLeft Party Right Party Radical Moderate Moderate Radical Country Far left Green Social democrats Christian Democrats/Conservative Liberal Far right Belgium Parti du travail de Belgique (PTB) Ecolo Parti Socialiste (PS) Centre Démocrate Humaniste (CDH) Mouvement Réformateur (MR) Parti Populaire (PP) Partij van de Arbeid van België (PVDA) Groen Vooruit (ex Sp.A) Christen-Democratisch en Vlaams (CD&V) Open Vlaamse Liberalen en Democraten (Open vld) Listes Destexhe DierAnimal Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie (N-VA) Démocrate Fédéraliste Indépendant (DéFI) Vlaams Belang (VB) The Netherlands Socialistische Partij (SP) Partij voor de Dieren (PvdD) Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA) ChristenUnie (CU) Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD) Forum voor Democratie (FvD) Bij1 GroenLinks (GL) DENK Christen-Democratisch Appèl (CDA) PDemocraten 66 (D66) Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) Boerburgerbeweging (BBB) VOLT Ja21 50PLUS Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij (SGP) Luxembourg La Gauche (Dei Lenk) Les Verts (Dei Greng) POSL – Parti Ouvrier Socialiste Luxembourg PCS – Parti Populaire Chrétien-Social PD – Parti Démocratique RAD – Parti réformiste d’alternative démocratique PIRATEN – Parti Pirate du Luxembourg Les Conservateurs (déi Konservativ) PCL – Parti communiste du Luxembourg 4.3 Dependent Variables

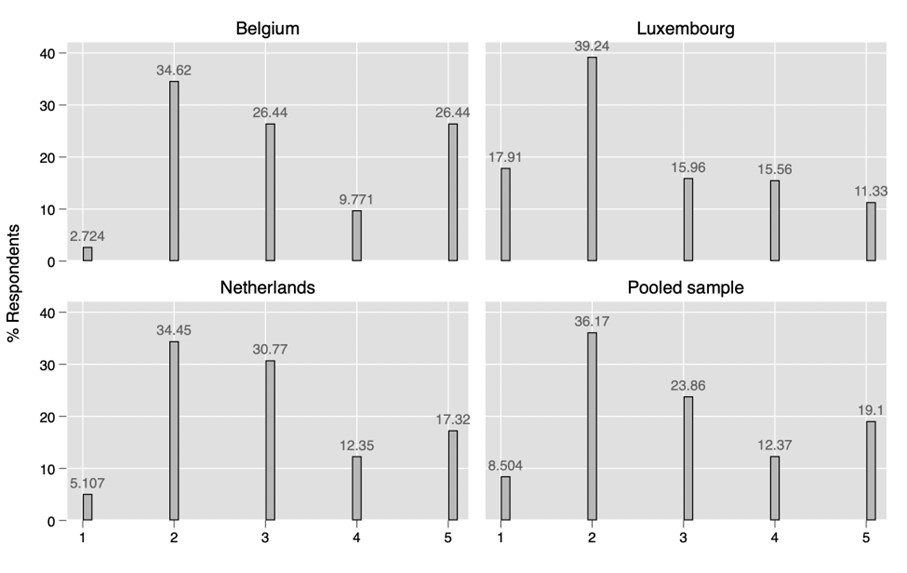

Support for referendums (H1-4). To measure the support for referendum among the voters, our surveys used the generic wording proposed by the European Social Survey. Respondents were asked to position themselves on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) about the following item: “It is important for democracy that citizens have the final say on political issues by voting in referendums”. We decided to keep this variable in its initial, ordinal format (Figure 1), where the higher the value, the more support. The median value is 3 for the pooled sample, which indicates a relatively neutral position among Benelux citizens. Luxembourg respondents stand out from the two other countries (NL = 3.0, BE = 3.2) with a mean below the neutral point (LU = 2.8). Yet, the mode is 3 in all the three countries.

Distribution of referendum support among voters

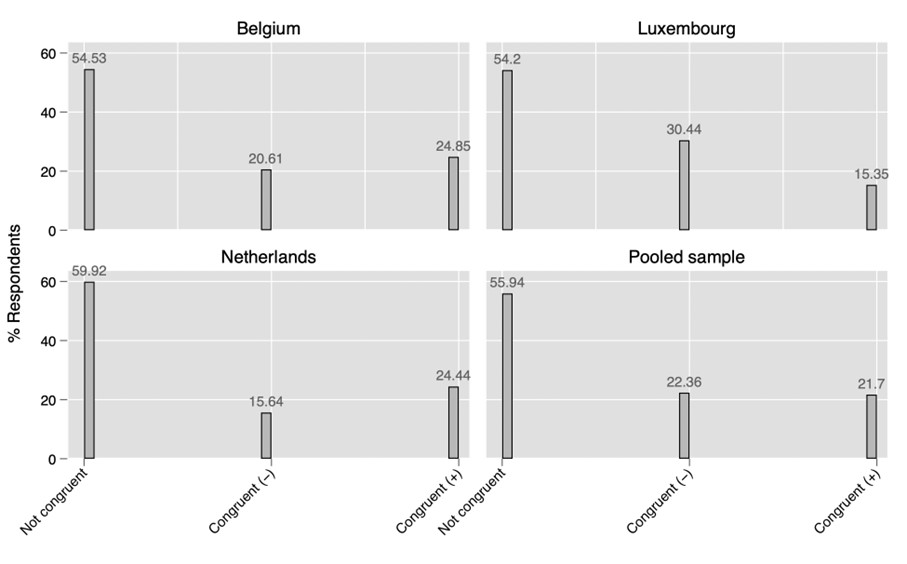

Party-voter congruence (H5-6). The second dependent variable uses both individual and party-level data. It puts in perspective the voter’s support towards referendums and the position of the party (s)he voted for in the last election. For each of the 41 parties’ manifesto, we have first identified whether there was a section dedicated to citizen participation, and then searched, through key words, whether there were specific claims to direct democracy and referendums for the 42 parties.5x The main key words for the search were ‘referendums’, ‘citizen initiatives’, ‘popular consultation’ and ‘direct democracy’. From this coding exercise that is summarised in Appendix 5, we found only two parties, both located in the Netherlands (the liberal party Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie and the small conservative party Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij) with explicit negative claims about referendums (Table 2).

Table 2 Examples of party negative claims on referendums“We are not in favor of referendums. The problem with referendums is that they reduce complex problems to a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’. As a result, people with constructive criticism can only completely reject or completely embrace a bill. A referendum also does not go well with representative democracy”.

VVD – Liberal party in the Netherlands“The disadvantage of (national) referendums is that they break into the representative democracy that we know in the Netherlands. In addition, a referendum by definition focuses on one specific subject, which makes a broader (interest) assessment difficult, if not impossible”.

SGP – Conservative party in the NetherlandsFinally, we ended up with a contrast between 20 parties that do not at all mention issues related to referendums in their manifesto (translating a rather indifferent or neutral stance on the topic, coded as 0) or do it negatively (i.e., the two Dutch parties, coded as 0 too) to 22 parties who do positively consider direct democracy as a potential policy instrument (coded as 1). Among the latter, we found clear nuances: some parties turn out to be more in favour of a consultative use (which may often coincide also with support for other policy making instrument like deliberative mini publics) and others for a more binding (and which focus on referendums as the main complementary process to elections) (Table 3).

Table 3 Examples of party positive claims on referendumsBinding referendum “People should therefore always be able to have their say on important decisions, for example through referendums”. Socialistische Partij (SP) – Radical left party in the Netherlands “Create a Citizens’ Legislative Initiative right that allows citizens to have a parliamentary assembly vote on legislative or constitutional proposals or, failing that, to submit them to a referendum with a possible counterproposal. Citizens must be fully informed about the modalities, contents and positions involved”. Ecolo – Green party in Belgium “Political power must move from party headquarters to the people. This can be done by organising binding referendums… Vlaams Belang wants to introduce binding plebiscites. Citizens should be able to take an initiative themselves provided they have the required minimum number of signatures”. Vlaams Belang – Radical-right party in Belgium “Referendum as emergency brake. It is good if voters can pull the emergency brake on laws passed by parliament in an extreme case. This boosts confidence in parliamentary democracy. There will be a binding, corrective referendum with an outcome threshold in line with advice from the Council of State: the result is only valid if the winning majority comprises at least half of the voters at the last elections to the House of Representatives”. ChristenUnie – Conservative party in the Netherlands Consultative referendum “The referendum must be accompanied by comprehensive and objective information beforehand, involving citizens as much as possible”. Parti Démocratique (PD) – Liberal party in Luxembourg “We also want to make greater use of popular consultations and/or referendums. We propose the establishment of direct consultations on social issues that concern citizens. This mechanism of direct democracy aims to strengthen citizen participation in the political decision-making process on an ad hoc basis”. Mouvement Réformateur (MR) – Liberal party in Belgium “D66’s analysis in its founding years still holds true today. Democracy and public administration need a thorough renovation. Therefore, when a new instrument like the consultative referendum is used for the first time, we embrace it and learn from it”. Democraten66 (D66) – Liberal party in the Netherlands Since we had not such a fine-grained information on the side of the voters (i.e., on preferences for binding or consultative referendums), party-voter congruence is finally operationalised as a categorical variable. The first, baseline group is composed of the voters who are not congruent with their party, meaning that they do not share the same position towards referendums (coded = 0, 56%). This points towards a frequent gap between voters’ demand and parties’ offer in terms of direct democracy. The second group encompasses the voters who are congruent with their party, but regarding a neutral or negative stance (coded = 1, 22.3%). The third and last group is made of the pro-referendum citizens who voted for a party that made favourable claim to referendum as alternative or complementary policy instrument in their manifesto (coded = 2, 21.7%) (Figure 2).

Distribution of party-voter congruence

4.4 Independent Variables

To test our hypotheses, we rely on different measurements of ideological preferences. They are first operationalised via three different attitudinal indicators. The first two are objective and intend to place respondents both on the economic and cultural dimension of the political space. The variable economic attitudes measures respondents’ stance on redistribution. (“It is the responsibility of the government to reduce the differences in income between people with high incomes and those with low incomes”. Strongly disagree = 1, strongly agree = 5), with respondents (strongly) disagreeing with the item expressing right-wing preferences. The variable cultural attitudes are opinions towards immigration. (“My country is made a worse place to live by people coming to live here from other countries”. Strongly disagree = 1, strongly agree = 5), with respondents scoring 4 or 5 being perceived as culturally right-wing. These two variables were both rescaled into 3 categories: left, centre (neutral) or right opinions. We rely also on left-right self-placement as a third, yet more subjective attitudinal indicator of left-right preferences. Respondents were asked to place themselves on a scale (“In politics people sometimes talk of ‘left’ and ‘right’. How would you place your views on the scale below?”) ranging from 0 (far left) to 10 (far right). Based on this, the variable left-right placement organises respondents into three groups: those who score lower than 4 (left leaning), 5 (centrist), or higher (right leaning). Moreover, to test H3, the variable extreme placement distinguishes those respondents who locate themselves on the extreme left or extreme right side of the axis (i.e., score 0-1, or 9-10, coded 1) from the moderate who score otherwise (coded 0). Along with the three attitudinal measurements, we also relied on a behavioural indicator. Party preferences are respondents’ voting choice in the last national election (“Which party did you vote for in the last national elections?”6x Since the electoral system is different in Luxembourg, citizens being allowed to allocate their vote to several parties/candidates, the question was the following: To which of the following political parties did you give most of your votes during the last 2018 national elections in Luxembourg?). Voters and their party were reorganised into four big categories, what allows to assess both left-right and radical-moderate preferences: radical left, mainstream left (social democrats and Greens), mainstream right (conservative and liberal) and radical right. From that, we also computed two dummies: radical party preferences (moderate = 0, radical = 1) and left-right party preferences (left = 0, right = 1). The respondents who cast a protest vote (blank or for a micro ‘other party’) or did not vote have been assigned a missing value (Table 4).

Table 4 Distribution of independent variablesN % Ideological preferences Pooled BE LU NL Economic attitudes Left 2,791 42.4 46.6 36.3 43.7 Centre/neutral 1,198 18.2 16.2 20.3 18.8 Right 2,593 39.4 37.2 43.4 37.5 Cultural attitudes Left 2,628 40.1 40.6 41.6 37.1 Centre/neutral 1,428 21.8 22.2 19.1 24.6 Right 2,503 38.1 37.2 39.3 38.3 Left-right self-placement Left 2,040 33.9 28.0 42.2 32.0 Centre/neutral 1,561 26.0 24.0 31.0 21.8 Right 2,412 40.1 48.0 26.8 46.2 Extreme self-placement Moderate 5,170 86.0 83.9 85.8 89.9 Extreme 843 14.0 16.1 14.2 10.1 Party preferences Left-right Left 2,008 42.5 48.5 41.4 35.1 Right 2,720 57.5 51.5 58.6 64.9 Radical-moderate Moderate 3,526 74.6 71.2 86.7 66.7 Radical 1,202 25.4 28.8 13.3 33.3 Left-right/radical-moderate Radical left 528 11.2 15.2 6.7 10.1 Moderate left 1,480 31.3 33.3 34.7 25.0 Moderate right 2,046 43.3 37.9 51.9 41.7 Radical right 674 14.2 13.6 6.7 23.2 4.5 Modelling Strategy

The first set of models intend to test H1 to H4, using the individual-level support for referendums as main dependent variable. To see the main patterns and relationships between our predictors and the ordinal dependent variable, we report the results of ordinal logistic regressions. Since there is a significant relation between left-right self-placement and party choice7x A chi-square test of independence indicated that there was a significant association: X2(6, N=4423) = 773.7, p =.000., we decided to proceed stepwise: M1a introduces attitudes (ideological preferences), M1b behaviours (party preferences), while M1c and M1d test the two at the same time. The second set of models analyses the capacity for parties and voters to be congruent on direct democracy stances (H5 and H6), using party preferences as the main predictor (and adding three-party-level controls). We ran two logistic regressions where the reference group (incongruent party voters) is either contrasted from voters who are congruent with their party on a positive view (M2a) or from those who adopt similar neutral/negative stance (M2b). To better interpret and compare effect sizes within and across logistic models (Menard 2011), we report in the main text standardised coefficient estimates for all the regressions. Although the standardisation of the main independent variables does not make much sense (as they are categorical), most controls are used in a continuous format and hence we preferred opting for scaling the whole model. We also replicated the first model by country subsample to see whether the results were holding in national samples. This was more complicated for the second model, as some categories could turn either missing (on the predictor side) or fully predicted (on the predicted side). The full specification and outcomes are available in Appendix 4. It is finally worth noting that for the main independent variables used in our models, the right-wing categories are used as a reference group to match with the direction taken by the hypotheses. Variation inflation factors (mean = 1.21 for M1, 1.53 for M2) do not stress any alarming problem of multicollinearity, staying in a decent range of values going from 1.0 to 2.3 in both models. Besides, we have overall stressed that correlations among the independent variables were rather moderate and acceptable.

4.6 Control Variables

Our models control for several other explanations of direct democracy support and hence include several control variables. For the explanation based on the level of socio-political resources, along with the socio-demographic profile (age and gender), we added (1) educational attainment (OECD classification recoded in three categories: low, middle and highly educated),(2) income security (“How you feel about your household’s income nowadays?” – find it very difficult to live = 1, living very comfortably = 5), (3) self-reported political interest (“How interested would you say you personally are in politics?” – not interested at all = 1, very interested = 4), (4) self-reported political competence/internal political efficacy (“Politics is too complicated for people like me” – strongly disagree = 1, strongly agree = 5).8x The scale has been reversed for the analyses to follow the direction of the other variables, i.e., the higher the value, the more resourceful. For the explanation related to political distrust, we relied on (5) trust in representative institutions, measured as how much confidence respondents have in parliament, political parties and politicians on a scale ranging from 1 (not trust at all) to 5 (high trust). The mean scores on these items were averaged, creating a scale of trust (Cronbach alpha = 0.89). To deal with populist predispositions, we included two items from Akkerman et al.’s (2014) classical battery on populist attitudes that was part of the survey. They tap into two relevant sub-dimensions of populist attitudes: (6) anti-elitism (“The political differences between the elite and the people are larger than the differences among the people” – strongly disagree = 1, strongly agree = 5) and (7) people-centrism (“The people, and not the politicians, should make our most important policy decisions” – strongly disagree = 1, strongly agree = 5). It is worth noting, first, that both items correlate positively together, yet weakly.9x Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient =.22 (p =.000). Likewise, anti-elitism associates positively with distrust but only moderately.10x Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient =.26 (p =.000). Second, despite the ordinal nature of all the individual-level control variables (except trust), they are treated as a continuous factor in all our models because they are not deemed to be discussed in the results section. Finally, in the second set of models where party-voter congruence is used as the main dependent variable, three-party-level controls were associated depending on the party that the respondent voted for: (8) party age (continuous factor based on the origins of the creation of the party organisation, proxy for institutionalisation), (9) parliamentary size (proportion of seats held in the national parliament during the legislature preceding the election, proxy for institutionalisation) and (10) incumbency (dichotomous variable indicating whether in power during the national legislature preceding the election, thereby controlling for a winner/loser gap) (Table 5).

Table 5 Descriptive statistics of the control variablesN Min Max Mean Individual-level (M1 and M2) Pooled BE LU NL Socio-economic resources (1) Educational attainment 6,655 1 3 2.3 2.3 2.4 2.2 (2) Income security 6,518 1 5 3.4 3.3 3.6 3.4 Political resources (3) Political interest 6,609 1 4 2.9 2.8 2.9 2.9 (4) Political competence (efficacy) 6,519 1 5 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 Political distrust (5) Trust in representative institutions 6,617 1 5 2.8 2.7 2.8 2.9 Populist attitudes 1 5 1.7 1.8 1.5 1.6 (6) Anti-elitism 6,580 1 5 3.3 3.5 3.1 3.3 (7) People-centrism 6,537 1 5 3.1 3.2 3.1 3.1 Party-level (M2 only) (8) Party age 4,799 3 176 66.1 88.7 59.8 41.4 (9) Party parliamentary size 4,799 0 35 12.7 9.2 19.7 9.9 (10) Party incumbency 4,799 0 1 .38 .30 .56 .31 -

5 Findings

Do left-wing people support more the use of referendum than right wing? This is a question that is addressed by the first model. The outcomes for the pooled sample (with country fixed effects) are summarised in the following table (full model specifications are available in Appendix 4). To better interpret the results and capture the significant differences in probability between the groups, we have systematically calculated and plotted the predictive margins of the independent variables that display statistically significant coefficient estimates. We also briefly discuss whether the results hold across countries (Table 6).

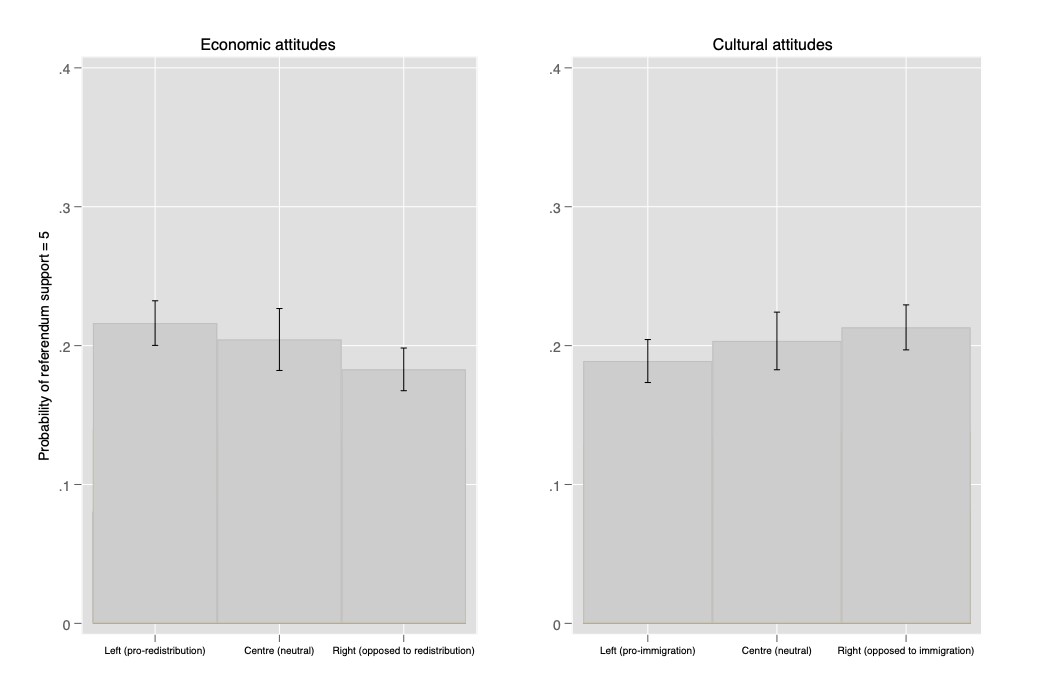

Table 6 Outcomes of the first modelDV = referendum support (1-5) M1a M1b M1c M1d Economic attitudes (ref = right) Left 0.052*** 0.057*** 0.057*** Centre 0.012 0.028 0.028 Cultural attitudes (ref = right) Left −0.029* −0.041* −0.041* Centre −0.010 −0.013 −0.013 Left-right self-placement (ref = right) Left −0.055*** −0.048** −0.048** Centre 0.027* 0.034* 0.034* Left-right party preferences Left −0.016 0.002 Extreme self-placement (ref = moderate) Extreme 0.014 0.016 0.016 Radical party preferences (ref = moderate) Radical 0.051*** 0.046** Radical X left-right preferences (ref = moderate right) Radical left 0.029 Moderate left 0.007 Radical right 0.045** Controls YES YES YES YES Country fixed effects YES YES YES YES N 5,457 4,395 4,097 4,097 Pseudo R square (%) 3.6 3.4 3.4 3.8 Model Ordered logistic regression The table displays only standardised coefficient estimates and their statistical significance (***p < =0.001, **p < = 0.01, *p = 0.05) for the main independent variables. The full model specification is available in Appendix 4. Regarding this first question, our analysis does not provide a univocal, straightforward answer. First, on the top of many other explanations, we still found that people who adopt a left-wing stance on the economy (pro-redistribution) have, as expected, higher probability to support referendums. The first graph in Figure 3 shows that the odds to strongly support referendums are significantly higher among people endorsing redistributive economic policies compared with those who favour economic individualism. Comparing the effect size with the other significant variables in the model reveals that economic attitudes are the most important ideological driver of referendum support among our respondents.

Predictive margins of economic and cultural attitudes

Although this finding could tend to provide evidence in favour of our first expectation (H1), generalising and saying that left-wing people are the main supporter of direct democracy would be a terribly misleading and simplifying claim. The reality appears to be more complex, as the same conclusion does not hold, in fact, when we look at the effects of the other attitudinal indicators. Counterintuitively, we found a reverse association between cultural attitudes and referendum support. As shown in the right-hand graph of Figure 3, people who adopt inclusive, pro-immigration opinions turn to have significantly lower probability to support referendums than the right-wing group. In the same direction, as the next figure illustrates, people who placed themselves on the left side of the political space have also lower chances of being positive towards the use of referendum than those on the right. All in all, this could mean two things. First, the left-right self-placement now better reflects the cultural divide, and what people understand by what is ‘left’ or ‘right’ refers much less nowadays to socio-economic views than how they position on socio-cultural issues (de Vries et al. 2013; Giebler et al. 2019). Second, some have suggested (Hooghe et al. 2002) that the economic and the cultural axes might be orthogonal. Hence, the supporters of direct democracy might be predominantly found in the quadrant where culturally right-wing and economically left-wing people meet. Hence, direct democracy support should be disentangled at the intersection of the socio-economic and cultural cleavages (Figure 4).

Predictive margins of left-right self-placement

Our model did not confirm either that left-wing party voters could be more strongly supportive of referendums than their right-wing counterparts. No statistical difference appears between these two groups. Overall, the results regarding the first hypothesis are thus mixed and H1 is rejected. This would probably deserve deeper investigation, even more when we see that the main pattern observed in the pooled analysis seems to be driven by the Belgian sample. If the results follow the same direction in the two other countries, the coefficients are not statistically significant. Moreover, one can notice two major findings contrasting again with the main hypothesis in these countries. First, only the relationship to party preferences turns significant in Luxembourg, and the moderate right-party voters appear to be the main supporters of direct democracy. In the Netherlands, we found that people who place themselves in the middle of the left-right axis have significantly more odds for referendum support. There, direct democracy support might be a matter of people who do not identify with left or right. Acknowledging that what is perceived as ‘left’ or ‘right’ might be greatly contextual (Zechmeister 2006), the analysis of the relationship between left/right positioning and direct democracy support would benefit from larger comparisons where contextual variables could be included in the analysis.

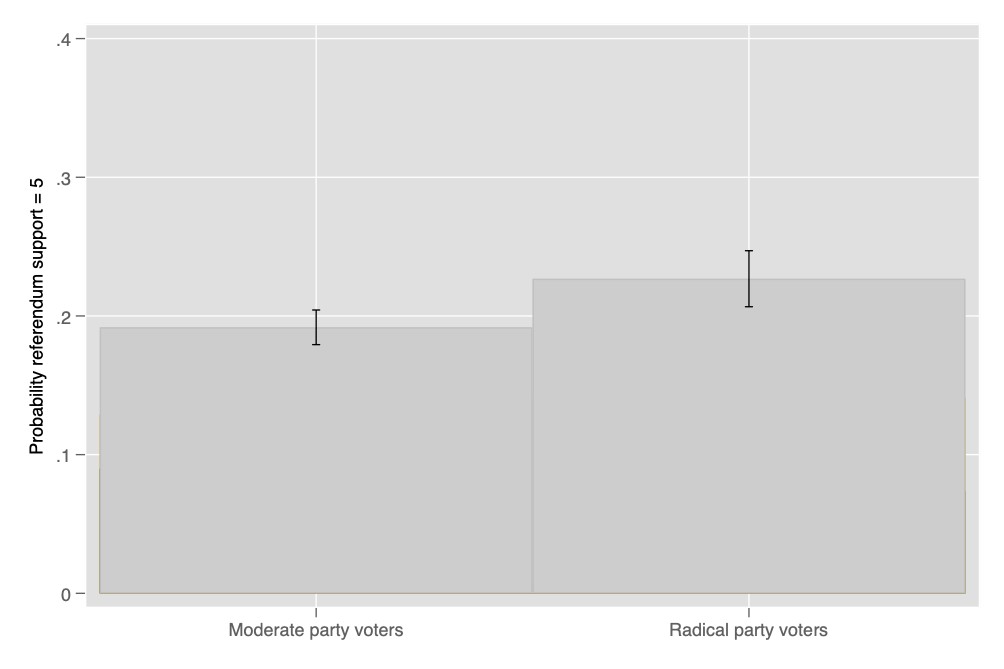

Do radical people support more strongly the use of referendums? Regarding this second question, we did not find significant results as far as the attitudinal measurement is concerned. Citizens who position themselves at the extreme of the left-right axis do not distinguish themselves from the others as being more supportive of referendum. Yet, we did observe a clearer line of demarcation when scrutinising the behavioural predictor, which reports a significant difference between radical and moderate party voters. As reported in the following figure, the odds of strongly supporting direct democracy are significantly higher among citizens who cast a vote for radical parties (Figure 5). This result goes totally in the direction of existing findings and our second hypothesis, although the latter is only partially corroborated. Moreover, by-country results seem to suggest that this finding is mainly driven by the Luxembourg sample, as it does not turn significant in the two other countries.Predictive margins of radical party preferences

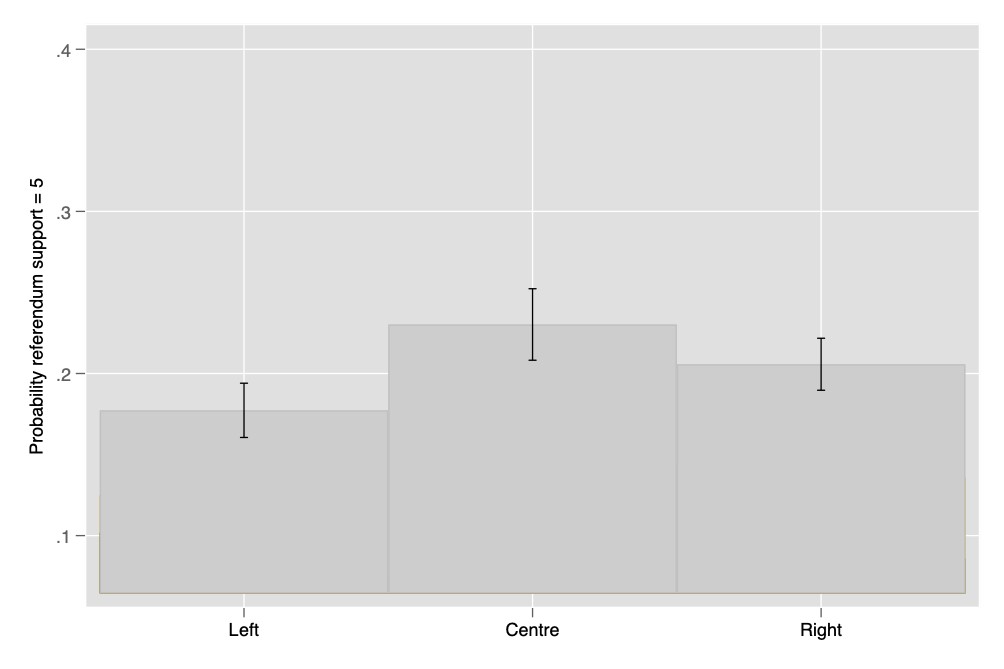

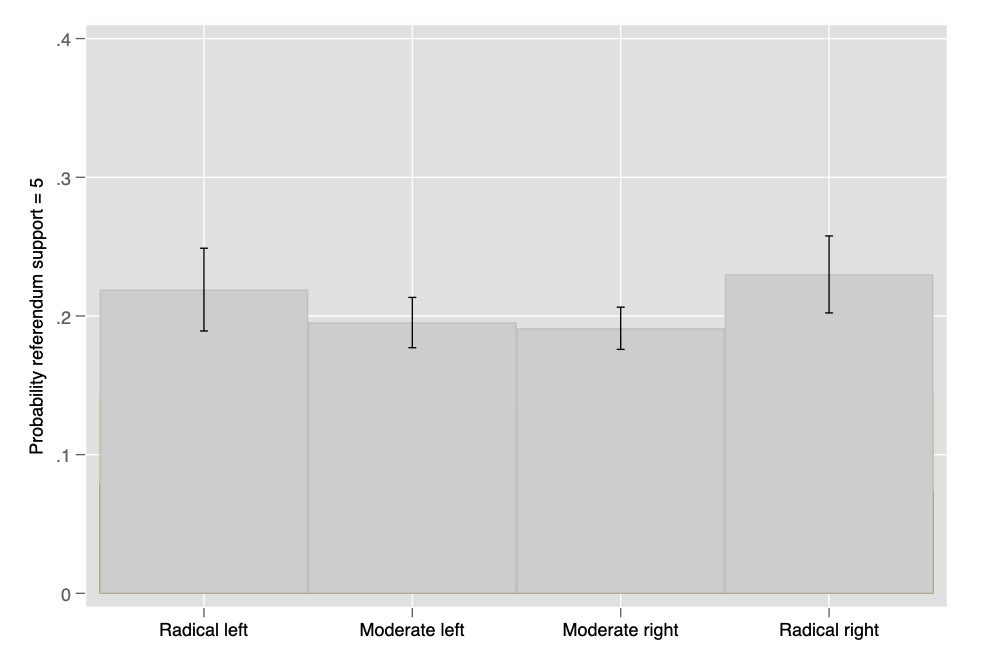

Furthermore, as recent works have shown as well, we did not observe a significant difference between radical left- or right-party voters in their chances to hold a positive opinion towards direct democracy, and so in all the three countries. This means that H3 is fully supported. Moreover, we argued that the left-right divide could be more important once looking at voters of ‘ideological’ parties. Yet, we found no evidence to claim that mainstream left-party voters could be more supportive of referendum than their moderate right-wing counterparts. Both groups display relatively similar chances to be positive towards direct democracy, as presented in the following figure. This implies that H4 is rejected. Additionally, we found a statistically significant difference on the right side of the political space, with radical right-party voters having higher odds than moderate right-party voters to hold a positive stance towards direct democracy (Figure 6).

Predictive margins of party preferences

From that, we ask ourselves how might this align with the supply side and whether parties were pushing for referendums. First, is it true that radical parties propose more than mainstream parties, making that they could meet the higher demand among their voters and bet on direct democracy as a mobilising issue? Second, among the moderate parties is it that right-wing ideologies are supporting less referendums than left-wing ones? Providing answers to these questions inevitably falls into discussing the proximity between parties and their voters on the issue of referendums (Table 7).

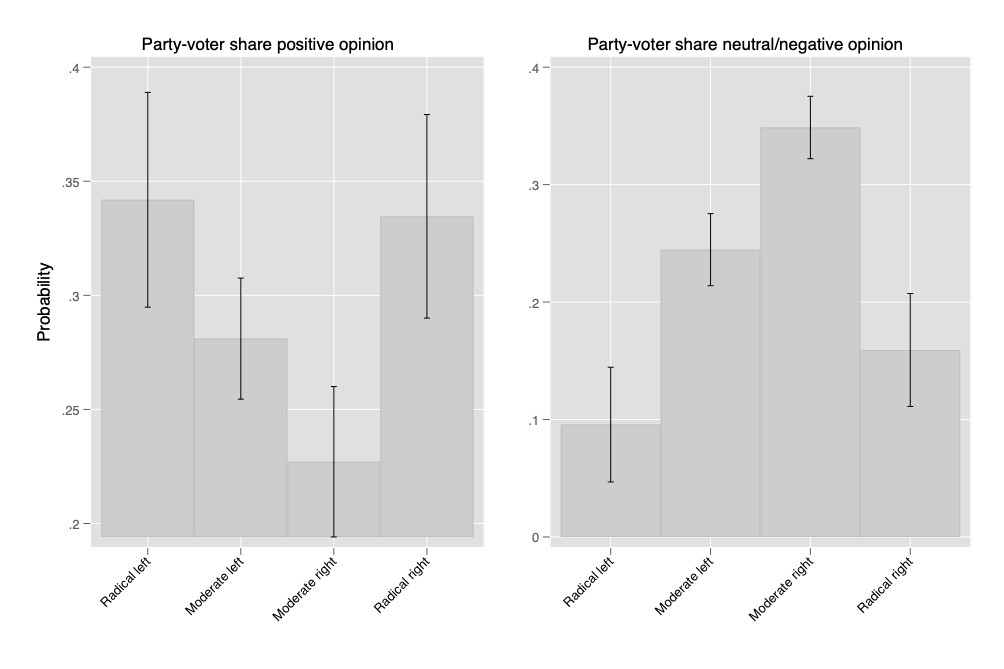

This leads us to the outcomes of the second model, where we focus more precisely on the relationship between ideology and party-voter congruence. The analysis performed on the pooled sample (regression table available in Appendix 5) confirms the descriptive variations. The results reveal that compared with their mainstream counterparts, radical parties and voters (both on the right and on the left) have a higher probability to be congruent and positive towards referendums, providing good empirical credit for H5 and supporting the findings provided by both supply and demand-side studies of referendum support. However, as reported in Figure 7, the difference is statistically significant mainly regarding mainstream right ideologies, which have the lowest probability of positive congruence. The non-significant difference with the mainstream left is probably due to the presence of the Greens, which have higher positive congruence than social democrats. Switching to the last hypothesis, the model found full support for H6, as mainstream left ideologies do convey more agreement on using more referendum as policy instrument. Moreover, mainstream right ideologies stand out from the left with significant higher odds of congruence on negative/neutral view, meaning that a majority of mainstream right parties and voters tend to agree that referendums are not a solution to implement.Table 7 Outcomes of the second modelDV = Party-voter congruence

(* Baseline = not congruent)M2a M2b Positive congruence * Negative congruence* Radical X left-right preferences (ref = moderate right) Radical left 0.109*** −0.233*** Moderate left 0.074** −0.118*** Radical right 0.111*** −0.170*** Controls YES YES Country fixed effects YES YES N 3,403 3,434 Pseudo R square (%) 4.7 14.7 Model Logistic regression The table displays only standardised coefficient estimates and their statistical significance (***p < = 0.001, **p < = 0.01, *p < = 0.05) for the main independent variables. The full model specification is available in Appendix 4. Predictive of party preferences (party-voter congruence)

Overall, we believe that the results of the second model are important as they point towards another view on the link between ideology and referendum. Besides radical ‘ideologies’ as main promoter of direct democracy, they reveal also a strong ideological resistance among moderate right parties and voters in Benelux countries. Given that mainstream right parties have frequently been in power over the last decades in these countries, this may potentially explain why the usage has remained limited. Yet, a crucial question relates to the relatively significant proportion of moderate right voters (especially among the conservative) who are positive towards referendums, but for which their party remains less responsive. This discrepancy might become strategically but also democratically challenging because, if these voters care about direct democratic reforms as an issue, they might be tempted to move towards a more radical option, which matches more with their view on how democracy should work and back it openly in their discourses. More generally, the capacity for moderate parties to deal with the heterogeneity of voters’ democratic preferences appear to be a key challenge for our current societies where radical parties are gaining ground. It also raises a promising path for further research.

-

6 Conclusion

While referendums have become an increasingly popular policy instrument in Europe over the last decades, Benelux countries have remained relatively spared by this evolution. This situation makes them particularly interesting cases to study who are the voters that would be more favourable (or not) to their use and how (some) parties are trying to respond to this demand in the electoral offer that they propose. In this article, we addressed whether ideologically based explanations for referendum support could hold when focusing on the three Benelux countries. Using survey data gathered in 2022 in the three countries, we first dismissed the idea that it could attract support from voters with a left-wing profile. More specifically, we show that, if the support for direct democracy was highly linked to left-wing economic position, it was also connected to right-wing cultural position and self-placement. This calls for further investigation that would consider economic and cultural attitudes as two orthogonal axes. As far as party preferences are concerned, we found the expected line of demarcation between radical and mainstream ideologies, with radical voters having greater odds of support of direct democracy, as well as more chances to find their party aligned on their demand. We also confirmed previous findings by showing no difference between radical right and left voters on these aspects. Among the moderate ones, our main finding is that mainstream left parties and voters tend to align more on positive opinions towards direct democracy than the mainstream right. Although the literature on direct democracy has mainly focused on populist/radical parties and voters, our findings regarding mainstream ideologies show a fundamental reluctance on the right side of the traditional political spectrum, or also a certain attachment to the status quo and the principles of representation. This majority consensus among right-wing parties and voters (but also present among moderate left) can probably partially account for why this mechanism has never really taken off in these countries, while it was the case elsewhere in Europe.

Finally, one major limitation of this study is perhaps to have too generic a measurement of referendum support, while, in fact, opinions both on the sides of the parties and voters are far more complex and highly contingent (e.g., on their binding or consultative nature, on their perceived favourable policy outcomes or still on the context, as the by-country analyses have suggested). This limitation opens the floor for further research. Many blind spots in the study of direct democracy and referendums remain. One is the lack of comparative efforts trying to articulate systematically the demand for direct democracy among the citizens and the political parties’ support for the mechanism, in their electoral manifesto or once they are in office (Close et al. 2022). This article was a first starting point to fill the gap. We would nonetheless need to pay more attention on the party awareness of the citizen demand for direct democracy and whether they integrate it in their electoral strategies. In that regard, the position of mainstream parties and their evolution would deserve some investigation. Another area of research is the link between parties and voters’ support for referendum and other forms of citizen participation (e.g., deliberative), or still how they articulate citizen participation with election or other forms of non-elected politics (e.g., technocracy). We could also dig more into the consequences of the use of referendums and how both parties and voters react once the instrument produces policy results. To conclude on the Benelux case, one crucial prospective question is also whether the electoral success of radical parties in these countries could end up into revitalizing the debate around the implementation and use of direct forms of democracy.For the Appendices referred to in this article, please see https://www.elevenjournals.com/tijdschrift/PLC/2023/1/PLC-D-22-00019A.

References Abrial, Stéphanie, Chloé Alexandre, Camille Bedock, Frédéric Gonthier and Tristan Guerra. 2022. “Control or Participate? The Yellow Vests’ Democratic Aspirations through Mixed Methods Analysis”. French Politics. https://link.springer.com/10.1057/s41253-022-00185-x.

Akkerman, Agnes, Cas Mudde and Andrej Zaslove. 2014. “How Populist Are the People? Measuring Populist Attitudes in Voters”. Comparative Political Studies 47(9): 1324-1353. doi: 10.1177/0010414013512600.

Anderson, Cameron and Elizabeth Goodyear-Grant. 2010. “Why Are Highly Informed Citizens Sceptical of Referenda?” Electoral Studies 29(2): 227-238. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2009.12.004.

Barnes, Samuel Henry and Max Kaase. 1979. Political Action: Mass Participation in Five Western Democracies. Sage Publications.

Bengtsson, Åsa and Mikko Mattila. 2009. “Direct Democracy and Its Critics: Support for Direct Democracy and ‘Stealth’ Democracy in Finland”. West European Politics 32(5): 1031-1048. doi: 10.1080/01402380903065256.

Bernhagen, Patrick and Michael Marsh. 2007. “Voting and Protesting: Explaining Citizen Participation in Old and New European Democracies”. Democratization 14(1): 44-72. doi: 10.1080/13510340601024298.

Bloquet, Claire, Isabelle Borucki and Benjamin Höhne. 2022. “Digitalization in Candidate Selection. Support and Resistance Within Established Political Parties in Germany”. Frontiers in Political Science 4. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.815513.

Bowler, Shaun, Todd Donovan and Jeffrey A. Karp. 2002. “When Might Institutions Change? Elite Support for Direct Democracy in Three Nations”. Political Research Quarterly 55(4): 731-754. doi: 10.2307/3088077.

Bowler, Shaun, Todd Donovan and Jeffrey A. Karp. 2006. “Why Politicians Like Electoral Institutions: Self-Interest, Values, or Ideology?” The Journal of Politics 68(2): 434-446.

Bowler, Shaun, Todd Donovan and Jeffrey A. Karp. 2007. “Enraged or Engaged? Preferences for Direct Citizen Participation in Affluent Democracies”. Political Research Quarterly 60(3): 351-362. doi: 10.1177/1065912907304108.

Brummel, Lars. 2020. “Referendums, for Populists Only? Why Populist Parties Favour Referendums and How Other Parties Respond”. IUC Working Paper Series. https://iuc.hr/index.php/iuc-working-paper-series/3.

Cain, Bruce E., Russell J. Dalton and Susan E. Scarrow. 2003. Democracy Transformed?: Expanding Political Opportunities in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford University Press.

Campbell, Angus et al. 1960. The American Voter. University of Chicago Press.

Ceka, Besir and Pedro Magalhães. 2016. “How People Understand Democracy. A Social Dominance Approach”. In How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy, éds. Monica Ferrin and Hanspeter Kriesi. Oxford University Press, 90-110.

Christensen, Henrik Serup and Åsa von Schoultz. 2019. “Ideology and Deliberation: An Analysis of Public Support for Deliberative Practices in Finland”. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 31(1): 178-194. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edx022.

Close, C., Pilet, J.-B., Rangoni, S., Vandamme, P.-É., 2022. La demande de démocratie directe, in: Magni-Berton, R., Morel, L. (Eds.), Démocraties directes, Études parlementaires. Bruylant, Bruxelles, 105-115.

Costello, R., Toshkov, D., Bos, B., Krouwel, A., 2021. Congruence between voters and parties: The role of party-level issue salience. European Journal of Political Research 60, 92-113. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12388

Dalton, Russell J., Wilhelm P. Burklin and Andrew Drummond. 2001. “Public Opinion and Direct Democracy”. Journal of Democracy 12(4): 141-153.

de Jonge, Léonie and Ralph Petry. 2021. “Luxembourg: The 2015 Referendum on Voting Rights for Foreign Residents”. In The Palgrave Handbook of European Referendums, Palgrave handbooks, éd. Julie Smith. Palgrave Macmillan, 385-403.

de Vries, Catherine E., Armen Hakhverdian and Bram Lancee. 2013. “The Dynamics of Voters’ Left/Right Identification: The Role of Economic and Cultural Attitudes”. Political Science Research and Methods 1(2): 223-238. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2013.4.

Donovan, Todd and Jeffrey A. Karp. 2006. “Popular Support for Direct Democracy”. Party Politics 12(5): 671-688. doi: 10.1177/1354068806066793.

Fernández-Martínez, José Luis and Joan Font Fábregas. 2018. “The Devil Is in the Detail: What Do Citizens Mean When They Support Stealth or Participatory Democracy?” Politics 38(4): 458-479. doi: 10.1177/0263395717741799.

Font, Joan and Carlos Rico Motos. 2023. “Participatory Institutions and Political Ideologies: How and Why They Matter?” Political Studies Review. doi: 10.1177/14789299221148355.

Gerbaudo, Paolo. 2021. “Are Digital Parties More Democratic than Traditional Parties? Evaluating Podemos and Movimento 5 Stelle’s Online Decision-Making Platforms”. Party Politics 27(4): 730-742. doi: 10.1177/1354068819884878.

Gherghina, Sergiu. 2019. “Hijacked Direct Democracy: The Instrumental Use of Referendums in Romania”. East European Politics and Societies: and Cultures 33(3): 778-797. doi: 10.1177/0888325418800553.

Gherghina, Sergiu and Jean-Benoit Pilet. 2021. “Do Populist Parties Support Referendums? A Comparative Analysis of Election Manifestos in Europe”. Electoral Studies 74. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102419.

Gherghina, Sergiu and Nanuli Silagadze. 2021. “Calling Referendums on Domestic Policies: How Political Elites and Citizens Differ”. Comparative European Politics. doi: 10.1057/s41295-021-00252-7.

Giebler, Heiko, Thomas M. Meyer and Markus Wagner. 2019. “From the European Debt Crisis to a Culture of Closed Borders: How Issue Salience Changes the Meaning of Left and Right for Perceptions of the German AfD Party”. Democratic Audit Blog. www.democraticaudit.com/.

Goovaerts, Ine, Anna Kern, Emilie van Haute and Sofie Marien. 2020. “Drivers of Support for the Populist Radical Left and Populist Radical Right in Belgium: An Analysis of the VB and the PVDA-PTB Vote at the 2019 Elections”. Politics of the Low Countries 2(3): 228-264. doi: 10.5553/PLC/258999292020002003002.

Grotz, Florian and Marcel Lewandowsky. 2020. “Promoting or Controlling Political Decisions? Citizen Preferences for Direct-Democratic Institutions in Germany”. German Politics 29(2): 180-200.

Hobolt, Sara B. 2016. “The Brexit Vote: A Divided Nation, a Divided Continent”. Journal of European Public Policy 23(9): 1259-1277. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2019.1583329.

Hobolt, Sara Binzer. 2006. “How Parties Affect Vote Choice in European Integration Referendums”. Party Politics 12(5): 623-647. doi: 10.1177/1354068806066791.

Hollander, Saskia. 2019. The Politics of Referendum Use in European Democracies. Springer.

Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Marks and Carole J. Wilson. 2002. “Does Left/Right Structure Party Positions on European Integration?” Comparative Political Studies 35(8): 965-989. doi: 10.1177/001041402236310.

Inglehart, Ronald. 1971. “The Silent Revolution in Europe: Intergenerational Change in Post-Industrial Societies”. American Political Science Review 65(4): 991-1017. doi: 10.2307/1953494.

Jacobs, Kristof, Agnes Akkerman and Andrej Zaslove. 2018. “The Voice of Populist People? Referendum Preferences, Practices and Populist Attitudes”. Acta Politica 53(4): 517-541.

Junius, Nino, Joke Matthieu, Didier Caluwaerts and Silvia Erzeel. 2020. “Is It Interests, Ideas or Institutions? Explaining Elected Representatives’ Positions Toward Democratic Innovations in 15 European Countries”. Frontiers in Political Science 2. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.584439.

Jurado, Ignacio and Rosa M. Navarrete. 2021. “Economic Crisis and Attitudes Towards Democracy: How Ideology Moderates Reactions to Economic Downturns”. Frontiers in Political Science 3. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.685199.

Kitschelt, Herbert P. 1988. “Left-Libertarian Parties: Explaining Innovation in Competitive Party Systems”. World Politics 40(2): 194-234. doi: 10.2307/2010362.

Klingemann, Hans-Dieter. 1979. “Ideological Conceptualization and Political Action”. In Political Action: Mass Participation in Five Western Democracies, éds. Samuel Henry Barnes and Max Kaase. Sage Publications, 279-304.

Koch, Cédric M., Carlos Meléndez and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2021. “Mainstream Voters, Non-Voters and Populist Voters: What Sets Them Apart?” Political Studies, Online First, 1-21. doi: 10.1177/00323217211049298.

König, Pascal D., Markus B. Siewert and Kathrin Ackermann. 2022. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Citizens’ Preferences for Democracy: Taking Stock of Three Decades of Research in a Fragmented Field”. Comparative Political Studies 55(12): 2015-2049. doi: 10.1177/00104140211066213.

Kostelka, Filip and Jan Rovny. 2019. “It’s Not the Left: Ideology and Protest Participation in Old and New Democracies”. Comparative Political Studies 52(11): 1677-1712. doi: 10.1177/0010414019830717.

March, Luke and Cas Mudde. 2005. “What’s Left of the Radical Left? The European Radical Left After 1989: Decline and Mutation”. Comparative European Politics 3(1): 23-49.

Menard, Scott. 2011. “Standards for Standardized Logistic Regression Coefficients”. Social Forces 89(4): 1409-1428. doi: 10.1093/sf/89.4.1409.

Mohrenberg, Steffen, Robert A. Huber and Tina Freyburg. 2021. “Love at First Sight? Populist Attitudes and Support for Direct Democracy”. Party Politics 27(3): 528-539. doi: 10.1177/1354068819868908.

Morel, Laurence. 2019. La question du référendum. Presses de Sciences Po.

Mudde, Cas. 2004. “The Populist Zeitgeist”. Government and Opposition 39(4): 541-563.

Nemčok, Miroslav, Peter Spáč and Petr Voda. 2019. “The Role of Partisan Cues on Voters’ Mobilization in a Referendum”. Contemporary Politics 25(1): 11-28. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2018.1543753.

Neuner, Fabian G. and Christopher Wratil. 2022. “The Populist Marketplace: Unpacking the Role of ‘Thin’ and ‘Thick’ Ideology”. Political Behavior 44(2): 551-574.

Niessen, Christoph. 2019. « When Citizen Deliberation Enters Real Politics: How Politicians and Stakeholders Envision the Place of a Deliberative Mini-Public in Political Decision-Making ». Policy Sciences 52(3): 481-503.

Núñez, Lidia, Caroline Close and Camille Bedock. 2016. “Changing Democracy? Why Inertia Is Winning Over Innovation”. Representation 52(4): 341-357. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2017.1317656.

Pascolo, Laura. 2020. “Do Political Parties Support Participatory Democracy? A Comparative Analysis of Party Manifestos in Belgium”. Constitution-making & Deliberative democracy Cost Action Working paper series, n 9.

Paulis, Emilien and Marco Ognibene. 2022. “Satisfied Unlike Me? How the Perceived Difference with Close Network Contacts Prevents Radical and Protest Voting”. Acta Politica. doi:10.1057/s41269-022-00242-x.

Pilet, Jean-Benoit, David Talukder, Maria Jimena Sanhueza and Sacha Rangoni. 2020. “Do Citizens Perceive Elected Politicians, Experts and Citizens as Alternative or Complementary Policy-Makers? A Study of Belgian Citizens”. Frontiers in Political Science 2. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.567297.

Quinn, Kevin M., Andrew D. Martin and Andrew B. Whitford. 1999. “Voter Choice in Multi-Party Democracies: A Test of Competing Theories and Models”. American Journal of Political Science 43(4): 1231. doi: 10.2307/2991825.

Qvortrup, Matt. 2018. “The History of Referendums and Direct Democracy”. In The Routledge Handbook to Referendums and Direct Democracy, éds. Laurence Morel and Matt Qvortrup. Routledge, 11-26.

Rojon, Sebastien and Arieke J. Rijken. 2020. “Are Radical Right and Radical Left Voters Direct Democrats? Explaining Differences in Referendum Support between Radical and Moderate Voters in Europe”. European Societies 22(5): 581-609. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2020.1823008.

Rojon, Sebastien, Arieke J. Rijken and Bert Klandermans. 2019. “A Survey Experiment on Citizens’ Preferences for ‘Vote–Centric’ vs. ‘Talk–Centric’ Democratic Innovations with Advisory vs. Binding Outcomes”. Politics and Governance 7(2): 213-226. doi: 10.17645/pag.v7i2.1900.

Rooduijn, Matthijs. 2014. “The Nucleus of Populism: In Search of the Lowest Common Denominator.” Government and Opposition 49(4): 573-599. doi: 10.1017/gov.2013.30.

Rooduijn, Matthijs, Wouter van der Brug and Sarah L. de Lange. 2016. “Expressing or Fuelling Discontent? The Relationship between Populist Voting and Political Discontent.” Electoral Studies 43: 32-40. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.006.

Scarrow, Susan E. 2017. “The Changing Nature of Political Party Membership”. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, Oxford University Press. https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-226.

Schuck, Andreas R.T. and Claes H. de Vreese. 2015. “Public Support for Referendums in Europe: A Cross-National Comparison in 21 Countries”. Electoral Studies 38: 149-158. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2015.02.012.

Stoychev, Stoycho P. and Gergana Tomova. 2019. “Campaigning Outside the Campaign: Political Parties and Referendums in Bulgaria”. East European Politics and Societies: and Cultures 33(3): 691-704.

Svensson, Palle. 2018. “Views on Referendums: Is there a Pattern?” In The Routledge Handbook to Referendums and Direct Democracy, éds. Laurence Morel and Matt Qvortrup. Routledge, 91-106.

Torcal, Mariano, Toni Rodon and María José Hierro. 2016. “Word on the Street: The Persistence of Leftist-Dominated Protest in Europe”. West European Politics 39(2): 326-350. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1068525.

van der Meer, Tom W. G., Jan W. Van Deth and Peer L. H. Scheepers. 2009. “The Politicized Participant: Ideology and Political Action in 20 Democracies”. Comparative Political Studies 42(11): 1426-1457. doi: 10.1177/0010414009332136.

Van Hauwaert, Steven M. and Stijn Van Kessel. 2018. “Beyond Protest and Discontent: A Cross-national Analysis of the Effect of Populist Attitudes and Issue Positions on Populist Party Support”. European Journal of Political Research 57(1): 68-92. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12216.

van Dijk, Lisa, Thomas Legein, Jean-Benoit Pilet and Sofie Marien. 2020. “Voters of Populist Parties and Support for Reforms of Representative Democracy in Belgium”. Politics of the Low Countries 2(3): 289-318. doi: 10.5553/PLC/258999292020002003004.

Walsh, Colm D. and Johan A. Elkink. 2021. “The Dissatisfied and the Engaged: Citizen Support for Citizens’ Assemblies and Their Willingness to Participate”. Irish Political Studies 36(4): 647-666. doi: 10.1080/07907184.2021.1974717.

Webb, Paul. 2013. “Who Is Willing to Participate? Dissatisfied Democrats, Stealth Democrats and Populists in the United Kingdom”. European Journal of Political Research 52(6): 747-772. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12021.