-

1 Introduction

This article explores reasoned orders issued by the Court of Justice (the Court) to reply to preliminary references of the national courts in the procedure for a preliminary ruling of Article 267 TFEU. Reasoned orders allow the Court to reply in a swift manner to preliminary references that raise no doubts. Concretely, Article 99 of the Rules of Procedure (RoP) of the Court of Justice state that the Court might issue a reasoned order in lieu of a judgment when the preliminary questions asked are identical to previous questions, if the reply clearly follows from the existing case law or if the answer admits no reasonable doubt.1x Rules of Procedure of the Court of Justice (2012) OJ (L 265), 1-42 (hereafter, Rules of Procedure). If any of these three conditions occurs, the Court might decide to reply by reasoned order, dispensing in that way with some of the procedural hurdles that replying with a judgment would entail, like waiting for the Advocate General in the case to deliver an Opinion.

Put simply, reasoned orders might be issued to reply to preliminary references when the Court considers EU law to be ‘clear’, either because the Court has previously established the meaning of an EU provision, or where the question asked is obvious. The issue then becomes when EU law can be considered to be ‘clear’. Even if indeterminate, the concept of ‘clear’ EU law is not unknown in the case law of the Court of Justice. Most famously, the Court coined the CILFIT doctrine, which allows national courts of last instance to not submit a question where the answer ‘admits of no doubt’, thus dispensing with their obligation to refer under Article 267(3) TFEU.2x Case C-283/81, CILFIT, ECLI:EU:C:1982:335, ‘The third paragraph of Article 177 of the EEC Treaty must be interpreted as meaning that a court or tribunal against whose decisions there is no judicial remedy under national law is required, where a question of Community law is raised before it, to comply with its obligation to bring the matter before the Court of Justice, unless it has established that the question raised is irrelevant or that the Community provision in question has already been interpreted by the Court of Justice or that the correct application of Community law is so obvious as to leave no scope for any reasonable doubt. The existence of such a possibility must be assessed in the light of the specific characteristics of Community law, the particular difficulties to which its interpretation gives rise and the risk of divergences in judicial decisions within the Community.’ In this sense, reasoned orders of Article 99 RoP work as a reversed CILFIT, where the Court, not the national courts, establishes when the answer to an EU question admits of no doubt. In this way, reasoned orders are a good window into what the Court considers to be settled EU law. This article argues that they are also good proxies to reflect on the operation and creation of trust between the Court and the national courts and tribunals.

The article posits that reasoned orders allow to research trust between the Court and national courts. They not only allow for considering the perspective of the Court in what it considers clear EU law, or that an EU question is settled,3x S.A. Brekke et al., ‘That’s an Order! How the Quest for Efficiency Is Transforming Judicial Cooperation in Europe’, 61 Journal of Common Market Studies 58 (2023). but also have a bearing on how the Court relates to the arguments and answers proposed by the national courts. Similarly, reasoned orders are a window into how national courts perceive their relationship with Luxembourg, and what they expect from it.

This article looks at the use of reasoned orders as proxies of trust and, thus, contributes to the research on trust in a multilevel judicial system. To this end, it analyses all Article 99 RoP orders issued by the Court of Justice during two full years (2020 and 2021). This comprises 82 reasoned orders, neatly divided in the two years. The size is similar to the number of orders published by the Court in the two years after. In particular, the article is concerned with what can be learnt from studying orders about the Court’s trust on its national counterparts, and of the latter in the Court. To do so, it identifies the aspects of the orders for reference (OfR) and the reasoned orders that serve to investigate this reciprocal trust.

The article proceeds as follows. Section 2 explains what are reasoned orders and how they are regulated in the RoP of the Court of Justice. Section 3 explores the limited literature on reasoned orders and uses it to hypothesise how orders can shed light on the Court’s trust on national courts and vice versa. The empirical materials are presented in Section 4, analysed in Section 5 and discussed in Section 6. The last section concludes with a reflection on how reasoned orders could be used to further enhance trust. -

2 Judgments in the Shape of Orders4x The expression is taken from U. Šadl et al., ‘Law and Orders: The Orders of the European Court of Justice as a Window in the Judicial Process and Institutional Transformations’, 1 European Law Open 549 (2022).

This section sets the stage by analysing the three main aspects of Article 99 RoP reasoned orders. First, it describes how Article 99 RoP reasoned orders are judgments sauf name (2.1). Second, the section posits that these reasoned orders might elucidate what the Court considers clear EU law and could thus be seen as a ‘reversed CILFIT’ (2.2.). Finally, it explains the procedure to issue an Article 99 RoP reasoned order.

2.1 Judgments in the Shape of Orders

Article 99 of the RoP establishes that the Court might reply to a preliminary reference by reasoned order in three cases. First, when the preliminary questions asked are identical to previous questions. Second, if the reply clearly follows from the existing case law. Third, if the answer admits no reasonable doubt. In other words, where EU law is clear, the Court might decide to reply to a national court with a reasoned order.5x For a historical account of the introduction of orders in the procedures of the Court see ibid.

Article 99 RoP reasoned orders do not entail a dismissal of the preliminary question or a non-reply.6x Cf. A. Dyevre, N. Lampach & M. Glavina, ‘Chilling or Learning? The Effect of Negative Feedback on Interjudicial Cooperation in Nonhierarchical Referral Regimes’, 10 Journal of Law and Courts 87 (2022). Far from that, reasoned orders are rulings in every aspect sauf name. They look like judgments and provide an answer to the preliminary question, akin to what a judgment would do. Put simply, they are judgments in the shape of orders.7x Šadl et al., above n. 4.

Reasoned orders are potentially timesavers, because Article 99 RoP dispenses with many of the procedural requirements, with which judgments must comply. Indeed, in 2005, the processing time for issuing orders was around 500 days shorter than for judgments.8x Brekke et al., above n. 3, at 6-7. It is then unsurprising that the Internal Guidelines of the Court encouraged its staff to ‘pleinement exploiter’ the use of orders, as they speed up the procedures and save a ‘travail inutile’.9x Court of Justice of the European Union, ‘Guide Pratique Relative Au Traitement Des Affaires Portées Devant La Cour de Justice’ para. 38. The Guidelines indicate and regulate the internal handling of affairs at the Court, with a particular emphasis in the internal procedures to follow, deadlines, services involved and so on. They are, as a rule, not available to the public but can be requested through access to documents. The request was not ignored, and the Court increasingly recurs to orders.10x Šadl et al., above n. 4. From 2000, we see an increased and steady use of reasoned orders at the Court.11x Brekke et al., above n. 3. This is not unique to the preliminary reference procedure, and is even more acute for the case of appeals, where orders are becoming the rule and judgments the exception.12x Ibid. See also M. Krajewski, Relative Authority of Judicial and Extra-Judicial Review: EU Courts, Boards of Appeal, Ombudsman (2021).2.2 Orders and ‘Clear’ EU Law

In CILFIT, the Court established that in some specific cases national courts of last instance did not have the obligation to refer a question under Article 267(3) TFEU. It decided that

the correct application of Community law may be so obvious as to leave no scope for any reasonable doubt as to the manner in which the question raised is to be resolved. Before it comes to the conclusion that such is the case, the national court or tribunal must be convinced that the matter is equally obvious to the courts of the other Member States and to the Court of Justice. Only if those conditions are satisfied, may the national court or tribunal refrain from submitting the question to the Court of Justice and take upon itself the responsibility for resolving it.

Judgments that are more recent might have watered down the criteria,13x M. Broberg, ‘Acte Clair Revisited. Adapting the Acte Clair Criteria to the Demands of the Times’, 45 Common Market Law Review 1383 (2008). but the threshold for national courts to apply CILFIT and not refer remains quite high.

Reversely, the Court has never explicitly stated when it considers a case to be legally beyond doubt and able to be replied to by order. This is surprising, if we consider that reasoned orders of Article 99 RoP appear as an inverse acte clair. After all, Article 99 RoP essentially says that where EU law is clear, the Court does not need to reply by judgment, and a reasoned order suffices. Yet, the efforts of the Court to specify the criteria for the application of the CILFIT doctrine by national courts have not been paired with a similar specification of criteria of what constitutes ‘clear’ EU law for the Court.14x Ibid., 1383.

The Court has not specifically addressed the similarity of Article 99 RoP and CILFIT in its judgments either. However, AG Tizzano in his Opinion on Lyckeskog specifically rejected any parallelisms between the two, arguing that ‘the prerequisites and purposes’ of both provisions ‘are, and must be, completely different’.15x Opinion in case C-99/00, Lyckeskog: ‘I must say, however, that even without a literal analysis of the said amendments I cannot see the connection between the proposal and the new wording of Article 104(3) of the Rules of Procedure. In the first case, the issue, so to speak, is the existence and degree of the doubts that the national court must have on a question of Community law in order to decide whether or not to refer it to the Court of Justice; in the second case, on the contrary, we are concerned with the doubts that the answer to the question may raise for the Court for the purpose of determining the procedure to be followed in replying to it. It is therefore obvious that the prerequisites and purposes of the third paragraph of Article 234 EC and Article 104(3) of the Rules of Procedure are, and must be, completely different, so that one cannot be cited for the purposes of the other and vice versa.’ Judge Edward, writing on a personal capacity, argued for a middle way, in which national supreme courts in doubt as to whether the CILFIT criteria apply could refer a question mentioning specifically the possibility to obtain a reply by reasoned order. If the Court disagrees, this would show that the reference was indeed needed.16x D. Edward, ‘National Courts – the Powerhouse of Community Law’, 5 Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies 1 (2003). The Court has never endorsed this view.

The difference of what is ‘clear’ for CILFIT and Article 99 RoP reasoned orders is hardly substantive: what is legally clear in terms of EU law should be relatively easy for the Court to define, as at least it has been able to decide in multiple occasions what was not clear. It is precisely on who holds the power to determine what is clear that the difference strikes.17x See along these lines Šadl et al., above n. 4; Brekke et al., above n. 3. Whereas CILFIT gives (some) leeway to the national courts to decide how EU law should be interpreted,18x But see Rasmussen’s critique and Mancini and Keeling’s take. H. Rasmussen, ‘The European Court’s Acte Clair Strategy in CILFIT’, 9 European Law Review 475 (1984); F. Mancini and D.T. Keeling, ‘From CILFIT to ERT: The Constitutional Challenge Facing the European Court’, 11 Yearbook of European Law 1 (1991). Cf. A. Arnull, ‘The Use and Abuse of Article 177 EEC’, 52 The Modern Law Review 622 (1989). Article 99 RoP reasoned orders allow the Court to keep the monopoly on defining what EU law is. To do so, it can decide which issues it wishes to revisit and which ones raise ‘no reasonable doubt’.2.3 The Procedure to Issue Reasoned Orders in Article 99 RoP

Article 99 RoP merely mentions the cases under which orders can be issued, but the Internal Guidelines of the Court offer some more guidance. The Guidelines of the Court are an internal document establishing the nitty-gritty regulation of the procedures at the Court.19x Court of Justice of the European Union, above n. 9. They indicate internal deadlines, how to compose the file of a case or the contents of the rapport préalable. For what concerns Article 99 RoP reasoned orders, the Guidelines provide information regarding the instances in which reasoned orders should be issued, as well as details on the procedure and the actors involved in the decision to issue a reasoned order.

The Internal Guidelines especially encourage the use of reasoned orders in two instances.20x Internal Guidelines, para. 41. First, when the Court has already interpreted the EU provision (primary or secondary law) to which the question refers, and the referred question merely regards the application of that interpretation to a concrete case. Second, when the question asked does not give raise to any ‘reasonable doubt’. According to the Court, this needs to be interpreted broadly (‘ces termes devant être compris dans une large acception’).21x Ibid. In particular, the Internal Guidelines posit that a strong indication that no reasonable doubt exists is that the Court subscribes to the pre-emptive opinion added by the national court to the OfR. To recall, Article 94 RoP encourages the national courts to include in the OfR a proposal as per the correct answer to the question asked. The literature refers to these statements as ‘preemptive opinions’.22x S.A. Nyikos, ‘Strategic Interaction among Courts within the Preliminary Reference Process – Stage 1: National Court Preemptive Opinions’, 45 European Journal of Political Research 527 (2006); R. Van Gestel and J. De Poorter, In the Court We Trust: Cooperation, Coordination and Collaboration between the ECJ and Supreme Administrative Courts (2019).

The role of the administrative services in the decision to issue a reasoned order is apparent in the Internal Guidelines. Prior to the assignment to a reporting judge, the Registry and the Research and Documentation Directorate (DRD) examine in parallel any case arriving at the Court. Both services produce reports for the President of the Court. The Internal Guidelines establish that the Registry, after registering the case, must send the President a ‘fiche objet’ indicating, among other things, ‘l’existence d’une jurisprudence de la Cour permettant de statuer sur cette affaire par voie d’ordonnance motivée’.23x Internal Guidelines, para. 2 in fine. The title ‘pour décision’ is added to the fiche.

While the Registry analyses the case, the DRD carries out its own preliminary analysis.24x Internal Guidelines, para. 8. The DRD is composed by national legal experts, who provide the Court with insights of the national legal systems and carry out an early review of all requests for a preliminary ruling.25x See the description of the Directorate at the Court’s website in CURIA – Research and Documentation Directorate, europa.eu (last visited 27 February 2024). From this early review, the DRD produces a report (fiche de préexamen) where it indicates any possibilities of replying to the question with a simplified procedure. If the DRD considers that a reply by reasoned order is possible, the fiche de préexamen will include a motivation, which can be directly used by the reporting judge in the case.26x Internal Guidelines, para. 16: ‘la fiche de préexamen comportera des éléments de motivation qui seront directement utilisables par le juge rapporteur dans l’élaboration de la décision mettant fin à l’instance?’

According to Article 99 RoP, the Court might decide ‘at any time’ to reply by reasoned order, ‘on a proposal of the Judge-Rapporteur and after hearing the Advocate General’.27x Art. 99 RoP. The Internal Guidelines provide some more detail on the procedure to issue reasoned orders, but, in the absence of other documents further elaborating on the procedure, the specifics remain obscure. From the Internal Guidelines, it seems clear that if the Judge Rapporteur considers that the reply to a reference offers no doubt, they can agree with the Advocate General to propose to the President of the Court that the relevant case law be forwarded to the referring court to inquire whether it wishes to maintain the reference.28x Internal Guidelines, para. 39.

If the national court does not reply, or replies to confirm that it wishes to maintain the reference, the Judge Rapporteur, in agreement with the Advocate General and the President of the Court, might decide to propose to the general meeting to reply to the reference with a reasoned order. The drafting of the Internal Guidelines at this point is ambiguous and seems to exclude the participation of the parties if a decision to propose to reply by reasoned order is taken.29x Internal Guidelines, para. 40 reads: ‘À défaut de réponse de la juridiction de renvoi dans le délai imparti – éventuellement assorti d’un délai de rappel – ou dans l’hypothèse où la juridiction de renvoi indique qu’elle souhaite maintenir sa demande de décision préjudicielle, le greffe en informe le Président, le juge rapporteur et l’avocat général, pour qu’ils se prononcent sur la nécessité de procéder à la signification de l’affaire aux intéressés visés à l’article 23 du statut ou sur l’opportunité de proposer à la réunion générale qu’il soit statué sur la demande de décision préjudicielle par la voie d’une ordonnance motivée au titre de l’article 99 du règlement de procédure.’ This raises questions about the adequacy of legal protection.30x T. Tridimas, ‘Knocking on Heaven’s Door: Fragmentation, Efficiency and Defiance in the Preliminary Reference Procedure’, 40 Common Market Law Review 9 (2003); Broberg, above n. 13; Brekke et al., above n. 3. However, the practice of the Court seems to be to inform the parties, at least sometimes. As Section 4 describes, for some of the reasoned orders recorded, the Court received submissions from the parties, so this seems to suggest that indeed parties are at times informed and that they submit their observations to the Court when this happens. This would mean that even in cases where the Court is satisfied that a reasoned order suffices to answer to the question, it still waits for the parties to have their say. The parties in any case would not be aware that the Court intends to reply by reasoned order. Neither would the national courts.31x This was not the case when reasoned orders were first introduced in the RoP in the 1990s. Up to 2005, the Court needed to inform the national court of the intention to reply by reasoned order. See Brekke et al., above n. 3.

For cases in which the parties submit observations, it is questionable what the procedural gain of adjudicating by reasoned order instead of judgment might be. Indeed, the RoP allow to dispense both with the Opinion of the Advocate General and the oral hearing in the proceedings leading to a judgment, where these are not deemed to add anything relevant for the decision. It would seem that, procedurally, a judgment without the Opinion of the Advocate general and the hearing is indistinguishable to a reasoned order. By consequence, both should lead to very similar, if not identical, procedural gains. It is thinkable, then, that the Court has reasons in mind, other than the mere saving of time, when deciding to reply by reasoned order. Section 3 further explores these possibilities, using the (scarce) literature on reasoned orders. In particular, it looks at the role of orders in building reciprocal trust between the Court and its national counterparts. -

3 The Use of Orders at the Court of Justice: Article 99 Reasoned Orders as Proxies for Trust

This section explores Article 99 RoP reasoned orders as proxies for trust. It first explores trust as a ‘two-sided issue’ (3.1.) to then review the literature on Article 99 RoP reasoned orders from the prism of trust (3.2.).

3.1 Trust, the Court and Reasoned Orders

Trust between courts remains a somehow untapped research resource.32x P. Popelier et al., ‘A Research Agenda for Trust and Distrust in a Multilevel Judicial System’, 29 Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law 3 (2022). This is particularly striking in the context of EU law and its multilevel judicial system, heavily reliant on the courts’ willingness to engage with each other and work together. The best example is perhaps the preliminary reference procedure of Article 267 TFEU, which is often conceptualised as a dialogue33x M. Claes and M. de Visser, ‘Are You Networked Yet? On Dialogues in European Judicial Networks’, 8 Utrecht Law Review 2 (2012); A. Rosas, ‘The European Court of Justice in Context: Forms and Patterns of Judicial Dialogue’, 1 European Journal of Legal Studies 2 (2007). or conversation34x M. Claes et al. (eds.), Constitutional Conversations in Europe: Actors, Topics and Procedures (2012). between the Court and its national counterparts. The procedure is inherently a system of cooperation between the national courts and the Court of Justice. This cooperation is indispensable for the procedure to work, and it is therefore thinkable that trust is an important aspect of the system.

The accounts of trust are varied,35x See a review of the relevant literature in Popelier et al., above n. 32. but within the preliminary reference procedure, it is studied most often from the perspective of national courts: national judges’ trust on the EU judicial system allows the system to function. It has been pointed out that the belief that the Court will provide clear guidance on EU law and not undermine the national legal order prompts the national judges to trust the Court.36x J.A. Mayoral, ‘In the CJEU Judges Trust: A New Approach in the Judicial Construction of Europe’, 55 Journal of Common Market Studies 551 (2017). This trust translates into an engagement with the Court, which materialises first in the referral of preliminary questions and, afterwards, in the application of the answers provided by the Court.

Yet, as highlighted by Van Gelsen and Poorter, trust is a ‘two-sided issue’, and the system depends on the trust that Luxembourg has in the national courts.37x Van Gestel and De Poorter, above n. 22, 185. For the functioning of the mechanism of Article 267 TFEU, the Court must necessarily trust the national courts and tribunals: as it lacks any autonomous enforcement capacity, the Court necessarily has to rely on national judges to implement its rulings. This ‘reversed trust’ can be researched by looking at the use of the different procedural tools of the Court. For instance, recent research has highlighted the increase of deference at the Court of Justice38x J. Zglinski, ‘The Rise of Deference: The Margin of Appreciation and Decentralized Judicial Review in EU Free Movement Law’, 55 Common Market Law Review 1341 (2018); L. López Zurita and S.A. Brekke, ‘A Spoonful of Sugar: Deference at the Court of Justice’, Journal of Common Market Studies (2023). and linked it to a growing maturity of the EU legal order and an increasing reliance of the Court on the national courts’ capacity to apply EU law correctly.39x Zglinski, above n. 38.

This article is concerned with investigating what reasoned orders can tell us about the trust or distrust of the Court in national courts and vice versa. Indeed, reasoned orders allow seeing trust operating both ways. First, they are a window into what the Court considers ‘clear’ EU law and shed light on the extent to which the Court is willing to ‘close’ EU law topics and hand them over to national courts. They also allow seeing whether the Court generally follows the opinions of the national courts when issuing reasoned orders, and if lower and higher courts receive a different treatment by the Court regarding orders. From the opposite side, they allow to investigate what national courts expect from the Court and their level of engagement with Luxembourg and EU law generally. Ultimately then, the article aims to explore whether reasoned orders contribute to enhancing trust or decrease it.

The following section reviews the literature on Article 99 RoP reasoned orders to flesh out the ways in which they can be used as proxies of trust.3.2 Reasoned Orders as Proxies of Trust

Article 99 RoP reasoned orders remain a relatively unused resource at the Court of Justice. This is true both for the Court itself, which is reticent to issue this type of reasoned orders,40x As mentioned above, this is not the case with reasoned orders dismissing appeals, which are now the norm rather than the exception. and for scholars, who have rarely looked into them. Yet, the trends seem to be reverting. In the past two decades, the Court is increasingly using reasoned orders.41x Brekke et al., above n. 3. The upward trend is visible for all types of reasoned orders but particularly acute for those replying to appeals. Šadl et al., above n. 4 show that in the preliminary reference procedure, the Court issued practically no orders in the 2000s, whereas there is a reasoned order for every ten judgments currently. For appeals, the increase is even more acute: in 2005, there was an order for every ten judgments, and now there are between two and three. Similarly, scholars have lately paid more attention to reasoned orders.42x Dyevre, Lampach & Glavina, above n. 6; U. Sadl et al., ‘That’s an Order! The Orders of the CJEU and the Effect of Article 99 RoP on Judicial Cooperation’ (Social Science Research Network 2020) SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3715514, https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3715514 (last visited 20 December 2020); Šadl et al., above n. 4. Their increased use, and the concern of the Court to simplify proceedings,43x This is apparent in the last proposal for reform of the Rules of Procedure of the Court, where the Court proposed to expand the simplified mechanism for the handling of appeals. See Amendment to Protocol No. 3 on the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union (2022) Interinstitutional File: 2022/0906 (COD). suggest that reasoned orders will continue to rise in the future, particularly if the trend in appeals is followed for preliminary references.

Even if on the rise, literature on orders of the Court in general and reasoned orders in particular is scarce. The following paragraphs review the current literature on Article 99 RoP reasoned orders to reflect on how these orders might shed light on the operation of trust between the Court and the national courts.

First, and perhaps most obviously, reasoned orders can be seen as the ultimate instrument showing trust towards national courts. A reduced reasoning could suggest that the Court relies on the national courts to apply EU law without any need to extend on a reasoning that the national court is perceived as not needing. Scholars have described similar uses of other procedural tools. For instance, Zglinski relates the increased use of deference in the rulings of the Court with a more matured legal order, in which the majority of questions have been settled.44x Zglinski, above n. 38, 1381. The necessary consequence of this argument is that the lack of reasoned orders, or its very scarce use by the Court, might be indicative of a lack of trust in national courts: the Court does not believe that a reduced reasoning/explanation is enough in the vast majority of cases and decides to reply with a full-fledged judgment.

On the opposite extreme, some scholars consider orders as formal dismissals.45x Dyevre, Lampach & Glavina, above n. 6. These formal or procedural dismissals encompass very different instruments issued by the Court: lack of jurisdiction of the Court, manifestly inadmissible references, Article 99 RoP orders and other instances in which the Court does not rule on the matter for different reasons relating to the requisites of Article 267 TFEU (lack of real controversy, hypothetical questions etc.). This research posits that the first two instances indicate a ‘poorly drafted reference’, whereas Article 99 RoP reasoned orders point to a ‘poor knowledge of EU law’.

In other words, reasoned orders might point to a ‘bad reference’ of the national court, that is, a reference that should not have been sent, for instance, because the question has already been resolved by the Court, of which the national court could (or even should) be aware. Some research indicates that national judges indeed take reasoned orders as a rejection of the order for reference/referred question in some cases.46x M. Glavina, National Judges as European Union Judges? Evidence from Slovenia and Croatia (2020), https://lirias.kuleuven.be/retrieve/559659 (last visited 19 May 2022). Seen from this perspective, not using reasoned orders might be a way of protecting trust: the Court might avoid orders as a way of preserving the trust of national courts, so as not to endanger cooperation.

Yet, the impact on national judges might be limited. In this sense, Dyevre et al. have also showed that orders trigger a learning effect in national courts. While previous research showed a certain chilling effect in national references after receiving an order,47x K. Leijon and M. Glavina, ‘Why Passive? Exploring National Judges’ Motives for Not Requesting Preliminary Rulings’, 29 Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law 263 (2022). more recent research suggests that national courts learn from receiving an order and are likely to resubmit (and get their references accepted) afterwards.48x Dyevre, Lampach & Glavina, above n. 6. Section 5 comprises some examples of this. Furthermore, the question arises as to whether reasoned orders are issued more in reply to questions by lower courts, thus potentially signalling a bigger distrust in those courts.

In between these positions, the use of Article 99 RoP reasoned orders might speak of different shades of trust. First, reasoned orders could indicate a limited trust, or a trust that is circumscribed to concrete types of questions/policy areas. In this sense, Broberg hypothesises that the Court could take into account the general relevance of the interpretation or the importance of the measure at stake when deciding to reply by reasoned order. The Court could be inclined to reply by reasoned order where it finds the answer straightforward or there is case law. These circumstances would be reflected in a ‘clear and often short line of argument’ in the decision of the Court. Yet, Broberg concludes that ‘the case law lacks coherence and is so opaque that it is not possible to conclude that the Court consistently has taken these factors into account.’49x Broberg, above n. 13, 1394.

Other literature points to the fact that orders might intend to signal something entirely different to national courts. Brekke et al. posit that the Court uses orders strategically.50x S.A. Brekke et al., ‘That’s an Order! How the Quest for Efficiency Is Transforming Judicial Cooperation in Europe’, 61 Journal of Common Market Studies 58 (2023). They explore the potential implication for Article 99 RoP reasoned orders (adjudicating orders in their terminology) in the dialogue with the national courts. Their analysis suggests that the Court is more likely to reply with a reasoned order to repeated or similar questions from the same Member State. The similarity of the questions from different Member States does not have the same effect.

This use of reasoned orders might signal trust to national courts in two ways. First, and more obviously, by keeping a low profile, Article 99 RoP reasoned orders grant an extra leeway to national courts in deciding issues that might have a strong link to a local context, or which relate to socially complicated disputes, which allows the Court to show that it trusts the national courts to apply a scant reasoning on their own. This would, however, presuppose that these are somehow complicated or politicised questions, which might not be the case for most cases in which the Court issues reasoned orders. Second, with these orders the Court indicates to its national counterparts that, on the specific topic, there is no need to keep referring the questions, as the Court has settled the case law and it is now time for the national courts to apply it to the cases before them autonomously.51x Without linking it to trust, this is one of the possible explanations provided, see ibid. -

4 Empirical Materials and Research Process

This section presents the research process to unpack the use of orders qualitatively.

The article qualitatively analyses all Article 99 RoPreasoned orders of the Court published in the years 2020 and 2021. This amounts to 85 orders, neatly distributed between the two years.52x The Court issued 36 Art. 99 RoP reasoned orders in 2020 and 46 in 2021. The numbers are very similar to orders in 2022 and 2023, with 39 and 36 orders, respectively. Until March 2024, the Court had already issued 5 reasoned orders. The orders are, as a rule, only available in the language of the proceedings and French, which is the working language of the Court. Translations to other languages are generally not made available. Any other type of reasoned orders, as those issued under Articles 170 bis and 181-182 RoP, regarding appeals, or Article 53 of the State of the Court, concerning inadmissibility, are not considered in this article.53x For an analysis, see Šadl et al., above n. 4.

A limitation of the analysis should be acknowledged and refers to the availability of the materials: the OfRs of the national courts are not generally available.54x The Court is starting to publish some of them, but so far only for judgments. Therefore, it is only possible to analyse the actual references of the national courts through their summary in the judgment of the Court itself, which means that any mention to the reference of the national court relies on the Court’s summary of it. Within these limitations, the analysis takes into account each side of the reasoned order: the question(s) by the national court and the reply itself of the Court.

The article identifies the aspects in the order that are relevant to the study of trust between the Court and the national counterparts. Beginning with the national court, the article first checks whether the national court included a pre-emptive opinion in the reference, that is, whether it indicated to the Court the answer it deemed appropriate to the question. Even if the analysis here relies on the summary provided in the reasoned order itself, the Court provides an at times quite lengthy sum-up of the national court’s reasoning for the question, particularly of any hint of an answer. The level of detail in the summary is also recorded: does the national court describe the problem at stake extensively, or does it provide only a succinct account, with only a few details? Furthermore, the article records whether the national court mentioned any case or cases explicitly. Such mentions can sometimes develop into a full discussion of a previous case of the Court and the gaps or doubts that the national court still holds after that decision. The framing of the question is also relevant, that is, whether the national court links the question/doubt to a specific problem in its Member State. For instance, the national court might mention that there are divergences in the interpretation across courts in the Member State, discuss the specificities of the national procedural law or describe previous decisions by the State’s Supreme or Constitutional courts. Any of this indicates that the question is linked, sometimes strongly, to a specific problem or question in a Member State, as suggested by some literature.55x Brekke et al., above n. 50. These are good proxies for trust, as they allow for checking not only whether or not the Court follows the opinion of the national courts but also and, more subtly, the extent to which the national court is familiar with EU law, thus probing into the intentions for a referral.

The reply of the Court of Justice can be recorded without any of the limitations indicated above for the national courts’ referrals. First, and most obviously, the analysis considers whether the Court explains why it replies with a reasoned order instead of a judgment. In particular, from the three possibilities opened by Article 99 RoP, it records which one the Court mentions, and whether it adds any extra explanation, which could shed light onto what is ‘clear’ EU law from the perspective of the Court. Similarly, when the national court has included a pre-emptive opinion, the analysis systematically checks whether the Court follows it. From the perspective of trust, these aspects indicate the extent to which the Court follows, or not, the argumentation or answer suggested by the referring court and the reasons prompting the Court to reply by reasoned order. As the Court might recur to a mere repetition of Article 99 RoP to justify issuing an order, the analysis records the number of cases cited by the Court, as well as whether the reasoned order includes any deference to the national court. The aim is to get an insight into the motivation of the Court, which can shed light on the amount of trust that it displays towards the national courts. -

5 Findings

This section presents the main findings of the analysis, which are discussed in Section 6.

Even if 70% of the references were sent by lower courts, the dataset includes references by Supreme and Constitutional Courts. Some of these courts, like the Italian Consiglio di Stato, repeatedly addressed the Court on the same topic and received a reasoned order. This is consistent with more general figures, which indicate that even if lower courts still refer more cases in absolute numbers, high courts refer more cases per court.56x T. Pavone, ‘Revisiting Judicial Empowerment in the European Union: Limits of Empowerment, Logics of Resistance’, 6 Journal of Law and Courts 303(2018); S.A. Brekke, ‘Speaking Law, Whispering Politics: Mechanisms of Resilience in the Court of Justice of the European Union’ (Thesis, European University Institute 2024) 56.

Section 2 explained that the Internal Guidelines are obscure about the need to inform the parties once the decision to reply by reasoned order has been taken. The findings would seem to suggest that the parties are indeed not notified or at least not for most cases. This is so as, for 70% of the cases, the information available in the reasoned order does not mention any interveners. Certainly, this could also mean that, when notified, none of the parties decides to submit interventions to the Court. Even if possible, this does not seem plausible, though, as for other cases, at least the European Commission and the Government from the Member State where the question originates intervened. In thirteen cases, only the plaintiff, the Government involved and the Commission intervened. A Member State other than the one from where the reference originated submitted observations in only eleven cases. In only one case, any other EU institution intervened.57x Order of the Court of Justice in case C-113/19, Luxaviation SA, ECLI:EU:C:2020:228. It is not apparent what the difference between cases with and without interveners could be.

Turning to the information provided by the national courts, the summary of the order for reference refers specifically to at least one judgment of the Court in 41% of the cases. Discussions of previous decisions of the Court are not uncommon. National judges include specific doubts arising from relevant decisions of the Court. This suggests that national courts are aware of previous replies of the Court yet do not consider those decisions to settle the question.

It is a common occurrence that the national court provides a very detailed discussion of any previous judicial decision concerning the case. For instance, in its decision in Andriciuc,58x Case C-186/16, Andriciuc and Others, ECLI:EU:C:2017:703. the Court established that, in the context of foreign exchange risk, an average consumer must be able to assess the potentially significant economic consequences of such a term with regard to their financial obligations. Citing the case and this conclusion of the Court, a Hungarian court asked for a clarification, namely, ‘whether such economic consequences must be explicitly apparent from the information provided by the Bank’.59x Order of the Court in case C-670/20, EP, TA, FV, TV, ECLI:EU:C:2021:1002, para. 15.

More strikingly, some orders are a reply to the second reference by the same national court, which is unsatisfied with the first preliminary ruling. For instance, the Spanish Court referring Gómez del Moral in 201860x Case C-125/18, Gómez del Moral Guasch, ECLI:EU:C:2020:138. sent another reference in 2020 as it considered that doubts remain as per the ‘effects of the interpretation of EU law in the national case’.61x Order of the Court in case C-655/20, Gómez del Moral Guasch II, ECLI:EU:C:2021:943, para. 24. Similarly, the national court of Amoena62x Case C-677/18, Amoena, ECLI:EU:C:2019:1142. repeated a reference two years later prompted ‘by the difficulties in understanding and applying paragraph 53 of the Amoena judgment’.63x Order of the Court in case C-706/20, Amoena, ECLI:EU:C:698, para. 21. A reasoned order is at times the reply to a second reference by the same court,64x Order of the Court in case C-81/20, Mitliv, ECLI:EU:C:2021:510. A part of the reference was again considered manifestly inadmissible by the Court. after the first attempt was considered ‘manifestly inadmissible’.65x Order of the Court in case C-9/19, Mitliv, ECLI:EU:C:2019:397. In most cases, however, the national courts do not mention a precedent of the Court, suggesting that the questions have not been settled. Some cases explicitly establish that the Court ‘has not yet been asked to interpret’ a given provision,66x Order of the Court in case C-598/20, Pilsētas zemes dienests. ECLI:EU:C:2021:971, para. 20: ‘La juridiction de renvoi relève que la Cour n’a pas encore été amenée à interpréter l’article 135 de la directive TVA lorsqu’est en cause la location de terrains sous un régime de bail obligatoire’ (my translation). or that, in a previous judgment, ‘the Court did not address’ an issue and that its case law ‘is not specific’.67x Order of the Court in case C-399/19, Autoritá per la Garanzie nelle Communicazioni, ECLI:EU:C:2020:346, para. 20. Other cases explicitly mention that the case law does not allow to provide an answer – see, for instance, Order of the Court in case C-248/20, Skellefteå Industrihus AB, ECLI:EU:C:2021:394, para. 29.

Furthermore, around a third of the cases contain a pre-emptive opinion, and practically all orders analysed contain a very long and detailed summary of the dispute. The summaries provide not only a comprehensive account of the facts behind the reference but frequently also a lengthy discussion of the legal problem at stake. Succinct summaries are anecdotal in the dataset.68x There are only five cases with very brief summaries. In one of them, the Court sent a request for more information to the national court; see Order of the Court of Justice in case C-255/20, Agenzia delle dogane e dei monopoli – Ufficio delle dogane di Gaeta, ECLI:EU:C:2021:926.

Over half of the references (62%) are framed in very specific terms, closely linked to the national context. References to the particularities of the national legal system are frequent. For instance, the national court might explain in detail the national tax system, national contract law,69x Order of the Court in case C-803/19, WWK Lebensversicherung auf Gegenseitigkeit, ECLI:EU:C:2020:413. or the meaning given to the term worker within national legislation.70x Order of the Court in case C-692/19, Yodel Delivery Network, ECLI:EU:C:2020:288, para. 16.

These OfRs discuss differences in the interpretation given to an EU provision or prior ruling of the Court by the domestic administrative and judicial authorities or highlight divergences in the interpretation among national courts. Frequently, the reference details the reasons why the referring court agrees or disagrees with the assessment of the other national court. For instance, a Hungarian court explicitly mentions the ‘contradictions between the way in which the law is interpreted by the tax authorities and the national courts’, which remain after three prior replies of the Court to other courts in Hungary,71x Order of the Court in case C-610/19, Vikingo Fővállalkozó Kft., ECLI:EU:C:2020:673, para. 18. while other cases mention divergent interpretations among national courts.72x Order of the Court in case C-709/18, UL VM, ECLI:EU:C:2020:411, paras. 19-21. Other preliminary references more generally refer to interpretations of their superior courts, without explicitly stating any conflict among the national judiciary. For example, on a question about the compensation for passengers of a delayed flight, the German referring court notes that the Federal Court holds a ‘large interpretation’ of the relevant provision.73x Order of the Court in case C-153/19, FZ, ECLI:EU:C:2020:412, para. 17.

References not so closely linked to the domestic context nevertheless include often very specific questions on EU law, like the exact interpretation of a paragraph from a previous decision of the Court, or the meaning of a term in a regulation or directive. For the latter cases, the questions are closely tied to the facts of the case, and frequently this is made obvious by the referring court. For instance, on a case on polluting emissions, the French referring court notes that clarification of the definition of ‘defeat device’ is needed to take a decision on the responsibility of the companies in the case and to assess whether the case should proceed to judgment after the instruction.74x Order of the Court in case C-690/18, CLCV and Others (Dispositif d’invalidation sur moteur diesel – II), ECLI:EU:C:2021:363, para. 49. A fifth of the references include this type of questions, of which half refer to the EU rules on compensation for plane delays and cancellations.75x Regulation (EC) No. 261/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 February 2004 establishing common rules on compensation and assistance to passengers in the event of denied boarding and of cancellation or long delay of flights, and repealing Regulation (EEC) No. 295/91 (2004) OJ (L 46), 1-8.

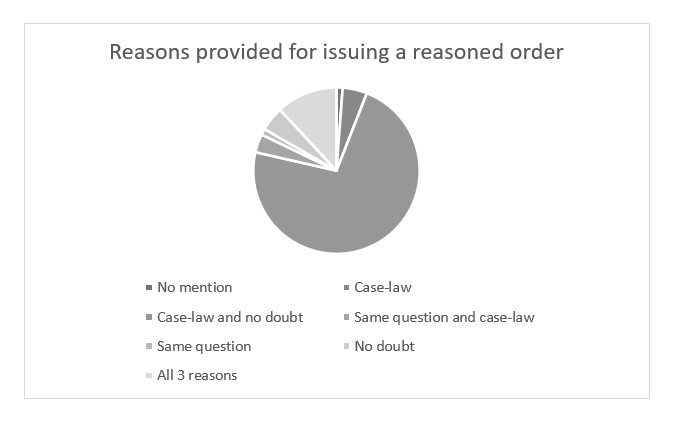

The reply of the Court never specifies the concrete reason justifying the reply by reasoned order instead of a judgment, but it refers to the reasons in Article 99 RoP without further elaborating in their application to the case. Figure 1 displays the results. In 70% of cases, the Court justified the use of Article 99 RoP on the existence of case law and the absence of doubts on the case. This is more common than cases where the question was considered identical to a previous question and the Court considers that there is case law. All reasons in Article 99 RoP are referred to in eight cases. Only a handful of cases signal only one of the circumstances in Article 99 RoP: no doubt (five cases), case law (two cases) and identical question (one case). In one case, the Court does not cite any of the circumstances in Article 99 RoP.Reasons provided by the Court to issue a reasoned order

The Court refers to only one case (or mostly to one case)76x The Court refers ‘mostly’ to one case where it cites a case to reply to the substance of the referred question, even if other cases are cited for other matters, like admissibility or pertinence of an urgent procedure. in 44% of cases. The rest of cases quote several cases. The Court explicitly declares the measure at stake incompatible only in 2% of the orders analysed. In 38% of cases, the Court explicitly declares the measure compatible. For the rest of cases, the Court does not explicitly pronounce itself on the compatibility of the measure. It follows the pre-emptive opinion of the national court in over half of the cases in which it was included in the reference.77x To recall, a pre-emptive opinion was added in a third of cases. Of those, the Court followed in in over half. Put differently, the Court followed the pre-emptive opinion of the national court in four out of seven cases including such opinions.

Finally, 60% of cases do not contain any deference to the national court. The rest of the cases contain deference, but this is limited to the verification of certain elements, clearly settled by the Court. -

6 Discussion: Unpacking Article 99 RoP Reasoned Orders at the Court

The first thing that emerges from the findings is the lack of clarity around reasoned orders. The reasons to issue an Article 99 RoP reasoned order remain unclear. The same is true for the elements of the procedure leading to a reasoned order. The analysis of reasoned orders leaves, indeed, ‘an impression of inconsistency’.78x Broberg, above n. 13, 1394.

The Court never explains why the answer to a given question is ‘clear EU law’ and merits the use of a reasoned order. It merely repeats the relatively vague criteria of Article 99 RoP. Yet, there is some variation in the way the Court refers to the different grounds in Article 99 RoP. The findings showed that for most cases the Court refers to the combination of the second (existence of case law) and the third (no doubt) grounds. It mentions the first circumstance (identical question) or any other combination of reasons only occasionally. This variation could point to some differences in what the Court considers clear EU law in the case. The findings suggest that cases in which the Court refers exclusively to one of the reasons of Article 99 RoP are more likely to cite only one case in the text of the reasoning, which could signify that these cases are somehow different for the Court.

The procedure by which the Court issues a reasoned order remains equally vague and suffers from the lack of transparency for which the Court is often criticised.79x A. Alemanno and O. Stefan, ‘Openness at the Court of Justice of the European Union: Toppling a Taboo’, 51 Common Market Law Review 97 (2014). The Internal Guidelines are ambiguous on the specifics, and the qualitative analysis shed light on these aspects only limitedly. The parties are notified in some instances, but it is not clear when or why. As explained in the previous section, for most of the orders analysed, there is no record of any interventions before the Court, which could mean that in those cases none of the parties submitted observations or that the Court does not always inform the parties when it decides to reply by reasoned order. This distinction suggests a dual strategy with orders. Some of them are deemed ‘unimportant’ or at least specific enough so that no further input from the parties is needed. For other orders though, the Court has a full-fledged procedure, sauf Opinion of the Advocate General, suggesting that those orders receive a different treatment. Yet, this emphasises the concerns about the adequacy of judicial protection in the cases discussed in the literature.80x Tridimas, above n. 30; Broberg, above n. 13. The concerns are particularly relevant if it is considered that individuals rely on the preliminary reference procedure as a means of protection of their rights, hence turning it into the key component of the EU system of judicial protection.

From the analysis of the orders, it is apparent that Article 99 RoP reasoned orders are not dismissals. Far from that, most of the orders analysed are actually very lengthy and include detailed discussions of the questions asked, sometimes even with very developed proportionality tests. Reasoned orders similarly do not seem to be the reply to ‘bad references’ showing a ‘poor knowledge of EU law’. Rather, references seem to display at least some knowledge of EU law. The numerous references to prior cases of the Court in the references by national judges, afterwards used by the Court in the reply, suggest that they are not only familiar with the case law of the Court and EU law but also willing to engage in an active dialogue with the Court. Nevertheless, further research is needed to fully unpack what OfRs unveil about the national courts’ knowledge of EU law.

The national courts also provided detailed accounts of the case in the main proceedings. Moreover, a third of the national courts followed the suggestion of the Court to include pre-emptive opinions in their references. This is consistent with previous literature, which identified these opinions in around 40% of referred cases.81x Nyikos, above n. 22; K. Leijon, ‘National Courts and Preliminary References: Supporting Legal Integration, Protecting National Autonomy or Balancing Conflicting Demands?’ 44 West European Politics 510 (2021); A.W. Ghavanini, ‘Can Two Walk Together, Except They Be Agreed? Preliminary References and (the Erosion of) National Procedural Autonomy’, 44 European Law Review 159 (2019). The Court followed these opinions in its replies in four out of seven cases including an opinion, which suggests that these were not ‘bad references’. Instances in which the Court does not admit the case, or admits it only partially, which could point to worse quality references, are only exceptional. Interestingly, these cases suggest that the learning effect described by some scholars is indeed taking place:82x Dyevre, Lampach & Glavina, above n. 6. a dismissed reference leads the national court to have a second one, which is successful, or a national court sends a second reference because it was not fully satisfied with the Court’s answer to the first. These second attempts by the same national court further suggest that national judges are not discouraged by reasoned orders and that their use does not undermine trust, a point that would require further research.

Are reasoned orders used for certain type of questions? The findings suggest so. First, as stated, the Court followed the pre-emptive opinion of the national court in over half of the cases where one was included. This number seems slightly higher than what has been found in previous studies looking at judgments.83x Ghavanini, above n. 81. The sample was quite small, so this is an area where future research is needed. In other words, the Court seems more willing to follow national courts when issuing reasoned orders. Seen from this perspective, reasoned orders serve as a ‘confirmation’ of the interpretation carried out by the national courts.84x Along the lines of Edward’s proposal in Edward, above n. 16.

The absence of any deference in most reasoned orders deviates from the general trend at the Court85x Zglinski, above n. 38; López Zurita and Brekke, above n. 38. but could suggest that the Court intends to give straightforward answers to the questions. Looking at the way the references are drafted, this seems to also be the expectation of the national courts. Broberg has suggested that the Court uses reasoned orders where there is prior case law and hence provides a ‘clear and often short line of argument’.86x Broberg, above n. 13, 1393. The findings partially confirm this. The Court indeed focuses on previous case law on most of the replies, and it is frequently the case that only a case or two are referred to in the order. Yet, reasoned orders are by no means short and can sometimes be quite long.

Second, the findings suggest that reasoned orders are used where the question referred by the national court forms part of a ‘local’ or ‘domestic’ dialogue, as was suggested by some literature.87x Brekke et al., above n. 3. References that asked about problems specific to a national legal order, oftentimes explicitly signalling divergent interpretations within the national judiciaries, received a reply in a reasoned order. The case of Spain is a good example. The reasoned orders replying to Spanish references in the cases analysed related to two legal issues, which has been rather prominent in national litigation: mortgage contracts with abusive clauses,88x The cases relate to Directive (EU) 2019/2161 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 amending Council Directive 93/13/EEC and Directives 98/6/EC, 2005/29/EC and 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the better enforcement and modernisation of Union Consumer Protection Rules (2019) OJ (L 328), 7-28. and temporary workers in the public sector.89x The cases relate to the application to public sector employees of the Council Directive 1999/70/EC of 28 June 1999 concerning the framework agreement on fixed-term work concluded by ETUC, UNICE and CEEP (1999) OJ (L 175), 43-48. For both areas, reasoned orders seem to be becoming the standard reply. In the period 2020-2021, the Court issued as many reasoned orders as judgments in matters related to the Framework Directive on Temporary Work, and more reasoned orders (six) than judgments for consumer protection (with another fifteen radiation orders after the references were withdrawn, which in all likelihood would have been reasoned orders).

Rather than indicating the willingness of the Court to ‘close’ a given topic, these replies can be read in terms of trust-building: the Court provides a detailed answer to a question probably lacking any general relevance but where the answer is of great importance for the national legal order. Hence, national courts can indeed trust that the Court will provide clear guidance on EU law questions.

Yet, the way in which the Court only sets loose criteria for issuing orders, and the lack of further clarification by the Court, contrast with the specific criteria of CILFIT, which suggests that the definition of clear EU law pertains exclusively to the Court or that the Court is determined to keep its monopoly over the interpretation of EU law. Together with the scarce use of orders at the Court, this questions the suggestion that the Court perceives the EU legal order as mature and the national courts ‘ready’ or ‘capable’ to apply EU law without much supervision. It begs the question of whether this is the more conducive manner to trust. -

7 Concluding Remarks: Reasoned Orders as Trust-Enhancers

Reasoned orders can boost (reciprocal) trust between the Court and its national counterparts and enhance dialogue. This would, however, require the Court to invest so that orders are more clearly part of a dialogue in which national courts are invited to take the central stage and trusted to apply EU law autonomously. Yet, for orders to work as trust-enhancers, the Court needs to construct them in such manner.

To do so, the Court should be more open in its use of reasoned orders. First, more clarity on the rules is needed. The procedure to issue orders is not regulated in the RoP, and it is only very vaguely sketched out in the Internal Guidelines. Informing national courts that the question will be replied to with a reasoned order could help build trust among the national courts and the Court and debunk any ideas that reasoned orders might indicate bad references. The findings suggested that this is not the case and that cases in which orders are issued display at least a fair knowledge of EU law and, in any event, a strong will to engage with EU law. Similarly, parties to the main proceedings should be able to know under which circumstances they will be allowed to share their views to the Court. If national courts were informed, they could further enlighten the Court on whether the submissions of the parties would be relevant to the proper solving of the case.

Furthermore, the Court would do well in explaining why and when EU law is clear, and a reasoned order is the most suitable way forward. As for the current practice, the Court merely mentions Article 99 RoP without explaining why the Article is to be applied in the case. The laconism stands in strong contrast to the straightforwardness required of national courts of last instance to apply CILFIT and suggests a willingness of the Court to avoid any impression of wanting to share the monopoly over the interpretation of EU law. The situation does not foster trust with national courts.

More clarity and openness, and a positive construction of reasoned orders, would show that the Court of Justice is ready to trust its national counterparts fully in the interpretation and development of EU law. In particular, the Court could use orders to indicate clearly the areas or topics in which it believes EU law to be settled and where, in principle, national courts can proceed without further ado. Such signal should be made in a more explicit manner. The Court’s recent turn to deference points to a willingness of the Court in this sense, which could be fully exploited in reasoned orders. At the same time, using reasoned orders in this manner could foster the trust of national courts, which would be able to rely on the Court to reply to a question that is important in the individual case, even if that question does not appear pertinent to general EU law. Nevertheless, the turn to reasoned orders should come with a reflection of how the Court sees its role and the dialogue with national courts, for reasoned orders have an impact on that dialogue. Given the relative youth of reasoned orders, shaping them carefully to enhance trust is within reach. - * Research for this article was funded by Danmarks Frie Forksningsfond Sapere Aude Grant N. 8046-00019A and the Danish National Research Foundation Grant no. DNRF 169 MOBILE, Center of Excellence for Global Mobility Law.

-

1 Rules of Procedure of the Court of Justice (2012) OJ (L 265), 1-42 (hereafter, Rules of Procedure).

-

2 Case C-283/81, CILFIT, ECLI:EU:C:1982:335, ‘The third paragraph of Article 177 of the EEC Treaty must be interpreted as meaning that a court or tribunal against whose decisions there is no judicial remedy under national law is required, where a question of Community law is raised before it, to comply with its obligation to bring the matter before the Court of Justice, unless it has established that the question raised is irrelevant or that the Community provision in question has already been interpreted by the Court of Justice or that the correct application of Community law is so obvious as to leave no scope for any reasonable doubt. The existence of such a possibility must be assessed in the light of the specific characteristics of Community law, the particular difficulties to which its interpretation gives rise and the risk of divergences in judicial decisions within the Community.’

-

3 S.A. Brekke et al., ‘That’s an Order! How the Quest for Efficiency Is Transforming Judicial Cooperation in Europe’, 61 Journal of Common Market Studies 58 (2023).

-

4 The expression is taken from U. Šadl et al., ‘Law and Orders: The Orders of the European Court of Justice as a Window in the Judicial Process and Institutional Transformations’, 1 European Law Open 549 (2022).

-

5 For a historical account of the introduction of orders in the procedures of the Court see ibid.

-

6 Cf. A. Dyevre, N. Lampach & M. Glavina, ‘Chilling or Learning? The Effect of Negative Feedback on Interjudicial Cooperation in Nonhierarchical Referral Regimes’, 10 Journal of Law and Courts 87 (2022).

-

7 Šadl et al., above n. 4.

-

8 Brekke et al., above n. 3, at 6-7.

-

9 Court of Justice of the European Union, ‘Guide Pratique Relative Au Traitement Des Affaires Portées Devant La Cour de Justice’ para. 38. The Guidelines indicate and regulate the internal handling of affairs at the Court, with a particular emphasis in the internal procedures to follow, deadlines, services involved and so on. They are, as a rule, not available to the public but can be requested through access to documents.

-

10 Šadl et al., above n. 4.

-

11 Brekke et al., above n. 3.

-

12 Ibid. See also M. Krajewski, Relative Authority of Judicial and Extra-Judicial Review: EU Courts, Boards of Appeal, Ombudsman (2021).

-

13 M. Broberg, ‘Acte Clair Revisited. Adapting the Acte Clair Criteria to the Demands of the Times’, 45 Common Market Law Review 1383 (2008).

-

14 Ibid., 1383.

-

15 Opinion in case C-99/00, Lyckeskog: ‘I must say, however, that even without a literal analysis of the said amendments I cannot see the connection between the proposal and the new wording of Article 104(3) of the Rules of Procedure. In the first case, the issue, so to speak, is the existence and degree of the doubts that the national court must have on a question of Community law in order to decide whether or not to refer it to the Court of Justice; in the second case, on the contrary, we are concerned with the doubts that the answer to the question may raise for the Court for the purpose of determining the procedure to be followed in replying to it. It is therefore obvious that the prerequisites and purposes of the third paragraph of Article 234 EC and Article 104(3) of the Rules of Procedure are, and must be, completely different, so that one cannot be cited for the purposes of the other and vice versa.’

-

16 D. Edward, ‘National Courts – the Powerhouse of Community Law’, 5 Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies 1 (2003).

-

17 See along these lines Šadl et al., above n. 4; Brekke et al., above n. 3.

-

18 But see Rasmussen’s critique and Mancini and Keeling’s take. H. Rasmussen, ‘The European Court’s Acte Clair Strategy in CILFIT’, 9 European Law Review 475 (1984); F. Mancini and D.T. Keeling, ‘From CILFIT to ERT: The Constitutional Challenge Facing the European Court’, 11 Yearbook of European Law 1 (1991). Cf. A. Arnull, ‘The Use and Abuse of Article 177 EEC’, 52 The Modern Law Review 622 (1989).

-

19 Court of Justice of the European Union, above n. 9.

-

20 Internal Guidelines, para. 41.

-

21 Ibid.

-

22 S.A. Nyikos, ‘Strategic Interaction among Courts within the Preliminary Reference Process – Stage 1: National Court Preemptive Opinions’, 45 European Journal of Political Research 527 (2006); R. Van Gestel and J. De Poorter, In the Court We Trust: Cooperation, Coordination and Collaboration between the ECJ and Supreme Administrative Courts (2019).

-

23 Internal Guidelines, para. 2 in fine.

-

24 Internal Guidelines, para. 8.

-

25 See the description of the Directorate at the Court’s website in CURIA – Research and Documentation Directorate, europa.eu (last visited 27 February 2024).

-

26 Internal Guidelines, para. 16: ‘la fiche de préexamen comportera des éléments de motivation qui seront directement utilisables par le juge rapporteur dans l’élaboration de la décision mettant fin à l’instance?’

-

27 Art. 99 RoP.

-

28 Internal Guidelines, para. 39.

-

29 Internal Guidelines, para. 40 reads: ‘À défaut de réponse de la juridiction de renvoi dans le délai imparti – éventuellement assorti d’un délai de rappel – ou dans l’hypothèse où la juridiction de renvoi indique qu’elle souhaite maintenir sa demande de décision préjudicielle, le greffe en informe le Président, le juge rapporteur et l’avocat général, pour qu’ils se prononcent sur la nécessité de procéder à la signification de l’affaire aux intéressés visés à l’article 23 du statut ou sur l’opportunité de proposer à la réunion générale qu’il soit statué sur la demande de décision préjudicielle par la voie d’une ordonnance motivée au titre de l’article 99 du règlement de procédure.’

-

30 T. Tridimas, ‘Knocking on Heaven’s Door: Fragmentation, Efficiency and Defiance in the Preliminary Reference Procedure’, 40 Common Market Law Review 9 (2003); Broberg, above n. 13; Brekke et al., above n. 3.

-

31 This was not the case when reasoned orders were first introduced in the RoP in the 1990s. Up to 2005, the Court needed to inform the national court of the intention to reply by reasoned order. See Brekke et al., above n. 3.

-

32 P. Popelier et al., ‘A Research Agenda for Trust and Distrust in a Multilevel Judicial System’, 29 Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law 3 (2022).

-

33 M. Claes and M. de Visser, ‘Are You Networked Yet? On Dialogues in European Judicial Networks’, 8 Utrecht Law Review 2 (2012); A. Rosas, ‘The European Court of Justice in Context: Forms and Patterns of Judicial Dialogue’, 1 European Journal of Legal Studies 2 (2007).

-

34 M. Claes et al. (eds.), Constitutional Conversations in Europe: Actors, Topics and Procedures (2012).

-

35 See a review of the relevant literature in Popelier et al., above n. 32.

-

36 J.A. Mayoral, ‘In the CJEU Judges Trust: A New Approach in the Judicial Construction of Europe’, 55 Journal of Common Market Studies 551 (2017).

-

37 Van Gestel and De Poorter, above n. 22, 185.

-

38 J. Zglinski, ‘The Rise of Deference: The Margin of Appreciation and Decentralized Judicial Review in EU Free Movement Law’, 55 Common Market Law Review 1341 (2018); L. López Zurita and S.A. Brekke, ‘A Spoonful of Sugar: Deference at the Court of Justice’, Journal of Common Market Studies (2023).

-

39 Zglinski, above n. 38.

-

40 As mentioned above, this is not the case with reasoned orders dismissing appeals, which are now the norm rather than the exception.

-

41 Brekke et al., above n. 3. The upward trend is visible for all types of reasoned orders but particularly acute for those replying to appeals. Šadl et al., above n. 4 show that in the preliminary reference procedure, the Court issued practically no orders in the 2000s, whereas there is a reasoned order for every ten judgments currently. For appeals, the increase is even more acute: in 2005, there was an order for every ten judgments, and now there are between two and three.

-

42 Dyevre, Lampach & Glavina, above n. 6; U. Sadl et al., ‘That’s an Order! The Orders of the CJEU and the Effect of Article 99 RoP on Judicial Cooperation’ (Social Science Research Network 2020) SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3715514, https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3715514 (last visited 20 December 2020); Šadl et al., above n. 4.

-

43 This is apparent in the last proposal for reform of the Rules of Procedure of the Court, where the Court proposed to expand the simplified mechanism for the handling of appeals. See Amendment to Protocol No. 3 on the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union (2022) Interinstitutional File: 2022/0906 (COD).

-

44 Zglinski, above n. 38, 1381.

-

45 Dyevre, Lampach & Glavina, above n. 6.

-

46 M. Glavina, National Judges as European Union Judges? Evidence from Slovenia and Croatia (2020), https://lirias.kuleuven.be/retrieve/559659 (last visited 19 May 2022).

-

47 K. Leijon and M. Glavina, ‘Why Passive? Exploring National Judges’ Motives for Not Requesting Preliminary Rulings’, 29 Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law 263 (2022).

-

48 Dyevre, Lampach & Glavina, above n. 6.

-

49 Broberg, above n. 13, 1394.

-

50 S.A. Brekke et al., ‘That’s an Order! How the Quest for Efficiency Is Transforming Judicial Cooperation in Europe’, 61 Journal of Common Market Studies 58 (2023).

-

51 Without linking it to trust, this is one of the possible explanations provided, see ibid.

-

52 The Court issued 36 Art. 99 RoP reasoned orders in 2020 and 46 in 2021. The numbers are very similar to orders in 2022 and 2023, with 39 and 36 orders, respectively. Until March 2024, the Court had already issued 5 reasoned orders.

-

53 For an analysis, see Šadl et al., above n. 4.

-

54 The Court is starting to publish some of them, but so far only for judgments.

-

55 Brekke et al., above n. 50.

-

56 T. Pavone, ‘Revisiting Judicial Empowerment in the European Union: Limits of Empowerment, Logics of Resistance’, 6 Journal of Law and Courts 303(2018); S.A. Brekke, ‘Speaking Law, Whispering Politics: Mechanisms of Resilience in the Court of Justice of the European Union’ (Thesis, European University Institute 2024) 56.

-

57 Order of the Court of Justice in case C-113/19, Luxaviation SA, ECLI:EU:C:2020:228.

-

58 Case C-186/16, Andriciuc and Others, ECLI:EU:C:2017:703.

-

59 Order of the Court in case C-670/20, EP, TA, FV, TV, ECLI:EU:C:2021:1002, para. 15.

-

60 Case C-125/18, Gómez del Moral Guasch, ECLI:EU:C:2020:138.

-

61 Order of the Court in case C-655/20, Gómez del Moral Guasch II, ECLI:EU:C:2021:943, para. 24.

-

62 Case C-677/18, Amoena, ECLI:EU:C:2019:1142.

-

63 Order of the Court in case C-706/20, Amoena, ECLI:EU:C:698, para. 21.

-

64 Order of the Court in case C-81/20, Mitliv, ECLI:EU:C:2021:510. A part of the reference was again considered manifestly inadmissible by the Court.

-

65 Order of the Court in case C-9/19, Mitliv, ECLI:EU:C:2019:397.

-

66 Order of the Court in case C-598/20, Pilsētas zemes dienests. ECLI:EU:C:2021:971, para. 20: ‘La juridiction de renvoi relève que la Cour n’a pas encore été amenée à interpréter l’article 135 de la directive TVA lorsqu’est en cause la location de terrains sous un régime de bail obligatoire’ (my translation).

-

67 Order of the Court in case C-399/19, Autoritá per la Garanzie nelle Communicazioni, ECLI:EU:C:2020:346, para. 20. Other cases explicitly mention that the case law does not allow to provide an answer – see, for instance, Order of the Court in case C-248/20, Skellefteå Industrihus AB, ECLI:EU:C:2021:394, para. 29.

-

68 There are only five cases with very brief summaries. In one of them, the Court sent a request for more information to the national court; see Order of the Court of Justice in case C-255/20, Agenzia delle dogane e dei monopoli – Ufficio delle dogane di Gaeta, ECLI:EU:C:2021:926.

-

69 Order of the Court in case C-803/19, WWK Lebensversicherung auf Gegenseitigkeit, ECLI:EU:C:2020:413.

-

70 Order of the Court in case C-692/19, Yodel Delivery Network, ECLI:EU:C:2020:288, para. 16.

-

71 Order of the Court in case C-610/19, Vikingo Fővállalkozó Kft., ECLI:EU:C:2020:673, para. 18.

-

72 Order of the Court in case C-709/18, UL VM, ECLI:EU:C:2020:411, paras. 19-21.

-

73 Order of the Court in case C-153/19, FZ, ECLI:EU:C:2020:412, para. 17.

-

74 Order of the Court in case C-690/18, CLCV and Others (Dispositif d’invalidation sur moteur diesel – II), ECLI:EU:C:2021:363, para. 49.

-

75 Regulation (EC) No. 261/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 February 2004 establishing common rules on compensation and assistance to passengers in the event of denied boarding and of cancellation or long delay of flights, and repealing Regulation (EEC) No. 295/91 (2004) OJ (L 46), 1-8.

-

76 The Court refers ‘mostly’ to one case where it cites a case to reply to the substance of the referred question, even if other cases are cited for other matters, like admissibility or pertinence of an urgent procedure.

-

77 To recall, a pre-emptive opinion was added in a third of cases. Of those, the Court followed in in over half. Put differently, the Court followed the pre-emptive opinion of the national court in four out of seven cases including such opinions.

-

78 Broberg, above n. 13, 1394.

-

79 A. Alemanno and O. Stefan, ‘Openness at the Court of Justice of the European Union: Toppling a Taboo’, 51 Common Market Law Review 97 (2014).

-

80 Tridimas, above n. 30; Broberg, above n. 13.

-

81 Nyikos, above n. 22; K. Leijon, ‘National Courts and Preliminary References: Supporting Legal Integration, Protecting National Autonomy or Balancing Conflicting Demands?’ 44 West European Politics 510 (2021); A.W. Ghavanini, ‘Can Two Walk Together, Except They Be Agreed? Preliminary References and (the Erosion of) National Procedural Autonomy’, 44 European Law Review 159 (2019).

-

82 Dyevre, Lampach & Glavina, above n. 6.

-

83 Ghavanini, above n. 81. The sample was quite small, so this is an area where future research is needed.

-

84 Along the lines of Edward’s proposal in Edward, above n. 16.

-

85 Zglinski, above n. 38; López Zurita and Brekke, above n. 38.

-

86 Broberg, above n. 13, 1393.

-

87 Brekke et al., above n. 3.

-

88 The cases relate to Directive (EU) 2019/2161 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 amending Council Directive 93/13/EEC and Directives 98/6/EC, 2005/29/EC and 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the better enforcement and modernisation of Union Consumer Protection Rules (2019) OJ (L 328), 7-28.

-

89 The cases relate to the application to public sector employees of the Council Directive 1999/70/EC of 28 June 1999 concerning the framework agreement on fixed-term work concluded by ETUC, UNICE and CEEP (1999) OJ (L 175), 43-48.

Erasmus Law Review |

|

| Article | Trust Issues? Article 99 RoP Reasoned Orders in the Preliminary Reference Procedure |

| Keywords | Court of Justice, reasoned orders, EU law, procedural tools, trust |

| Authors | Lucía López Zurita * xResearch for this article was funded by Danmarks Frie Forksningsfond Sapere Aude Grant N. 8046-00019A and the Danish National Research Foundation Grant no. DNRF 169 MOBILE, Center of Excellence for Global Mobility Law. |

| DOI | 10.5553/ELR.000269 |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Abstract Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

Lucía López Zurita, "Trust Issues? Article 99 RoP Reasoned Orders in the Preliminary Reference Procedure", Erasmus Law Review, 1 (incomplete), (2024):

|