-

1 Introduction

‘Contractual equilibrium’ is a significant concern of the doctrine of change of circumstances or the doctrine of hardship. For example, ‘hardship’ under Article 6.2.2 (Definition of Hardship) of the UNIDROIT Principles is defined as an event that ‘fundamentally alters the equilibrium of the contract either because the cost of a party’s performance has increased or because the value of the performance a party receives has diminished’. Again, Article 6.2.3 (Effects of Hardship) of the UNIDROIT Principles refers to the same concern by providing that the court may ‘adapt the contract to restore its equilibrium’ if it finds hardship.

In applying the doctrine of change of circumstances, how judges determine contractual equilibrium has been disrupted by an unexpected circumstance and how they restore it are intriguing enquiries of theoretical and practical importance. This matters to ensure this doctrine would not erode the sanctity of contract or pacta sunt servanda (Latin for ‘agreements must be kept’), the cornerstone principle of contract law since Roman law.1x E. Hondius and H.C. Grigoleit (ed.), Unexpected Circumstances in European Contract Law (2011), at 15. This also helps to understand the nuanced judicial intervention with contractual relationships in the name of fairness. Despite a few discussions of the Chinese doctrine of change of circumstances in English literature2x There are four English articles discussing the doctrine of change of circumstances under Chinese law. Three of them are L.L. Wang, ‘Force Majeure, the Principle of Change of Circumstances, and the Doctrine of Frustration during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Commercial Leases and Judicial Responses in China and New Zealand’, 11(2) Peking University Law Journal 199-220 (2024); M. Chen, ‘A Comparative Study of the Chinese Change of Circumstances and the UK Contract Frustration’, 5(5) International Journal of Law and Political Science 105-9 (2023); L. Chen and Q. Wang, ‘Demystifying the Doctrine of Change of Circumstances under Chinese Law – A Comparative Perspective from Singapore and the English Common Law’, 6 Journal of Business Law 475-96 (2020). These generally compared the rationale and function of the Chinese doctrine of change of circumstances with the common law doctrine of frustration or force majeure. In the author’s opinion, they are not functionally similar, although both are concerned with post-conclusion unexpected circumstances. This is because, accurately speaking, there is no equivalent in common law to the Chinese doctrine of change of circumstances under the Civil Code. A detailed discussion can be found in A. Loke, ‘The Frustration Doctrine and Leases: Lessons from the Hong Kong Covid-19 Litigation’, 3 Erasmus Law Review (2023). The author argues that it is essential to have a good understanding of the Chinese doctrine of change of circumstances before conducting a meaningful comparative study with the equivalent doctrine in other jurisdictions (esp. the civil law jurisdictions that recognise the doctrine of change of circumstances). The fourth one is Q. Liu, ‘Force Majeure or Change of Circumstances: An Enduring Dichotomy in Chinese Law?’ in H. Jiang and P. Sirena (eds.), The Making of the Chinese Civil Code (2023) 77-93. It will be referred to later in this article. and more Chinese publications regarding the doctrine3x There have been about sixty Chinese journal articles concerning the doctrine of change of circumstances after May 2020 according to the CNKI database. Among them, good-quality articles include X. Bing, ‘Concrete Construction of the Doctrine of Change of Circumstances’(情势变更原则的具体化构建), 2 Law Application (法律适用) 94-105 (2022), and Z. Guangxin, ‘Systematic Consideration of the System of Change of Circumstances’ (情势变更制度的体系性思考), 2 Legal Science (法学杂志) 1-12 (2022). published after the Civil Code,4x The Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China (中华人民共和国民法典) (promulgated by the National People’s Congress on 28 May 2020, effective on 1 January 2021). little literature has comprehensively analysed the theoretical basis for the Chinese doctrine of change of circumstances and carefully examined the nuanced judicial reasoning in deciding each ingredient of the doctrine through a large-scale study of real cases. This article, for the first time, systematically elaborates on the Chinese judicial analytical approaches in applying the doctrine of change of circumstances by examining 5,391 judicial decisions and clearly identifies the relationships between the three doctrines regarding unexpected circumstances (i.e. the doctrine of change of circumstances, the doctrine of frustration of the purpose of the contract and the doctrine of force majeure) under contract law. It provides a deep understanding of the Chinese doctrine of change of circumstances operating in real life and the latest Chinese experiences for nourishing the comparative law discourse of the rules of unexpected circumstances.

The article is divided into five parts. Section 2 presents a theoretical basis for the doctrine of change of circumstances, including the shared assumption theory and the contractual equilibrium theory. Section 3, after introducing the latest statutory provisions regarding the doctrine of change of circumstance under Chinese contract law,5x Chinese contract law has developed since 1981. In addition to some general rules about contract law set out in the 1986 General Principles of Civil Law (民法通则), there were three specific contract laws in the 1980s: the 1981 Economic Contract Law (经济合同法), the 1985 Foreign-related Economic Law (涉外经济合同法) and the 1987 Technology Contract Law (技术合同法). The 1999 Contract Law (合同法) unified the previous specific contract laws and established a comprehensive legal framework of contract law in China. It included two parts: General Provisions and Nominate Contracts. These laws were all made by the national legislature, the National People’s Congress and its Standing Committee. Afterwards, the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issued two sets of judicial interpretations regarding the application of the 1999 Contract Law in 1999 and 2009. It made a separate judicial interpretation concerning the application of the law of sale contracts in 2012. In May 2020, the National People’s Congress made the Civil Code (民法典), which incorporates most of the provisions of the 1999 Contract Law into its Book Three titled ‘Contracts’. As a result, the 1999 Contract Law and the 1999 and 2009 judicial interpretations of contract law became null. The judicial interpretation regarding the law of sale contracts was amended to adapt to the Civil Code in December 2020. In December 2023, the SPC promulgated its judicial interpretation regarding applying Title One General Provisions of Book Three Contracts of the Civil Code (最高人民法院关于适用《中华人民共和国民法典》合同编通则若干问题的解释). In summary, the major sources of the current Chinese contract law consist of the Civil Code and the 2020 and 2023 judicial interpretations of contract law. presents the Chinese judicial practice in deciding each legal ingredient of the doctrine by examining relevant judicial decisions. Section 4 further analyses the Chinese judicial analytical approaches to deciding the existence of a change of circumstances, the categorisation of the disputed contractual equilibrium, the restoration of the contractual equilibrium, and their comparative law implications. The final section concludes the article. -

2 Theoretical Basis

The doctrine of change of circumstances is also called clausula rebus sic stantibus (Latin for ‘the clause of things thus standing’) as it developed in medieval canon law.6x Hondius and Grigoleit, above n. 1, at 16-17. Literally, clausula rebus sic stantibus7x The literal meaning is, ‘All conditions must be the same as they were when I made the promise if you mean to hold me bound in honour to perform it’. states that a contract is binding so long as and to the extent that things remain the same as they were at the time of the conclusion of the contract. The condition of constant circumstances was generally constructed as an implied tacit clause of all contracts.8x Hondius and Grigoleit, above n. 1, at 18. With the rise of the will theory in the early-modern period, the jurists (Hugo Grotius, in particular) based clausula rebus sic stantibus on the will of the parties and limited it to two situations: first, a supervening change of circumstances would frustrate a promisor’s specific expectation of an unchanged course of affairs; second, a new, unexpected situation would contradict the will of a promisor, such as the performance would violate a law or the performance appeared to be too ‘grievous and burdensome either regarding the condition of human nature absolutely considered or by a comparison of the persona and the thing in question with the very end of the engagement’.9x Ibid., at 23.

However, assuming that a promisor expects an unchanged course of affairs in all contracts is artificial and unreal. Moreover, it is difficult to evidence that an unexpected situation contradicts the will of a promisor when their will is unclear and unknown. The approach of an implied tacit condition of constant circumstances cannot satisfactorily provide a theoretical basis for the doctrine of change of circumstances. Alternative theoretical bases are to be explored. The author argues that the shared assumption theory and the contractual equilibrium theory should combine to serve such a purpose.2.1 The Shared Assumption Theory

Under the principle of sanctity of contract, a contract formed by the law has the force of law between the contracting parties because of their mutual agreements based upon party autonomy. With the shared assumption theory, this principle is conditioned on the fact that the parties have shared correct assumptions on which their mutual agreements are based.10x M. Eisenberg, ‘Impossibility, Impracticability, and Frustration’, 1 Journal of Legal Analysis 211, at 211 (2009). As Prof. Eisenberg pointed out, shared assumptions are often tacit because the parties may take them for granted or do not have infinite time and cost to make all shared assumptions explicit.11x Ibid., at 212.

There are two situations where the parties’ shared assumptions turn out to have been incorrect, and a strict application of the principle of sanctity of contract in these situations may cause unfairness and, thus, require judicial relief. First, the parties share a misconception concerning the shared assumption regarding present events (such as both parties did not know that the subject matter had been destroyed before the time of conclusion), thus causing their agreements to contradict their true intention. This situation concerns a ‘mutual mistake’ that renders the contract voidable.

Second, due to the limits of foresight, the parties cannot reasonably anticipate a subsequent change of circumstances when concluding their contract. In other words, the unexpected circumstance is beyond their shared assumption, so they have never considered and assessed the risk of that future circumstance, or it contradicts their shared assumption, thus substantially influencing their prospective assessment and allocation of the relevant risks involved in their transactions. For example, the contracting parties in Krell v. Henry12x [1903] 2 KB 740. had the tactic shared assumption that the King’s coronation would be held on the proclaimed route on the proclaimed days. However, unexpected to both parties, the King became ill, and the scheduled coronation and procession were postponed. The situation concerns ‘unexpected circumstances’ that may justify judicial intervention.13x It is worth noting that ‘unexpected circumstances’ are not only concerned with the doctrine of change of circumstances but also the doctrine of frustration of the purpose of the contract and the doctrine of force majeure.

The shared assumption theory provides a theoretical justification for why the parties may seek judicial relief where an unexpected circumstance contradicts the shared assumption on which their contract is based. In terms of change of circumstances, this echoes German jurist Paul Oertmann’s theory of Wegfall der Geschäftsgrundlage (German for ‘collapse of the foundation of contract’, which is the mutually consented presupposition of a contract)14x Hondius and Grigoleit, above n. 1, at 30. – when the circumstances that constituted the foundation of a contract changed fundamentally or the foundation of a contract collapsed after the conclusion of the contract, the court might exonerate the parties from the performance of the contract or change its terms to restore a just contractual equilibrium.15x B.S. Markesinis, H. Unberath & A. Johnston, The German Law of Contract (2006), at 323. His theory was adopted by the German reichsgericht (German for ‘Reich Court’) in the 1920s as the German courts began to take into consideration social changes that might substantially change the basis of contracts (e.g. the changed economic circumstances during and after the First World War). The doctrine remained a judge-made law until it was codified into the German Civil Code in 2002.16x Section 313 of the German Civil Code (Interference with the basis of the transaction).2.2 The Contractual Equilibrium Theory

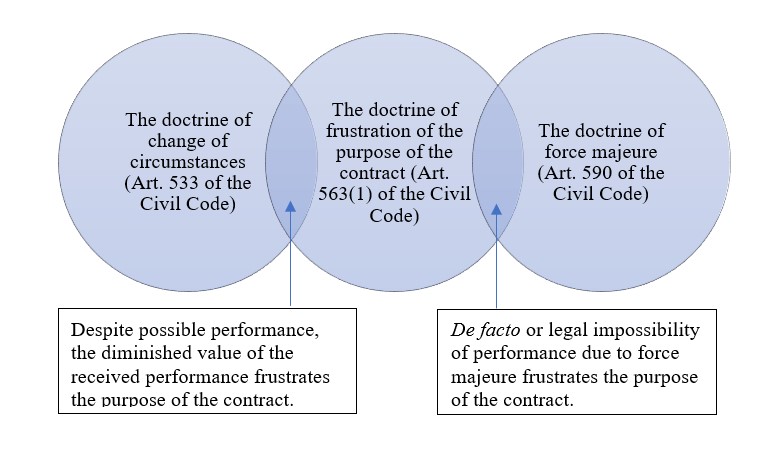

When an unexpected circumstance contradicts the shared assumption of the parties, according to the different degrees of impact the unexpected circumstance has on contract performance, there are three categories associated with different legal consequences (see Table 1).17x The first two categories of unexpected circumstances are relevant to but beyond the scope of this article. However, the article will discuss the relationships between the three doctrines regarding unexpected circumstances in Section 4. First, if an unexpected circumstance renders a party’s performance impossible, temporarily or permanently, the party will be relieved from the liability for non-performance. This is termed ‘the doctrine of force majeure’. Second, if an unexpected circumstance frustrates the purpose of the contract, either party can unilaterally terminate the contract and be released from performing their unperformed obligations after the termination. This is often termed ‘the doctrine of frustration’ (in a narrow sense). The third category is that an unexpected circumstance causes hardship in performance and thus disrupts the ‘contractual equilibriums’ that the parties have achieved through their negotiations and the conclusion of the contract, although the performance remains possible. In this circumstance, the adversely affected party can request renegotiation and, if renegotiation fails, then resort to the court for termination or modification of the contract. This is called ‘the doctrine of change of circumstances’ or ‘the doctrine of hardship’.

Contractual equilibrium means a balance between performance and counter-performance18x A. Dawwas, ‘Alteration of the Contractual Equilibrium under the UNIDROIT Principles’, 2010 Pace International Law Review Online Companion [xvi], at 5 (2010). between the parties based on their shared assumptions at the time of conclusion. As long as the contract is made upon the parties’ voluntary and genuine intention, it is deemed that they have prospectively assessed and allocated the foreseen risks before mutually agreeing to the arrangements of performance and counter-performance. Contractual equilibrium is presumed. However, a post-conclusion unforeseeable change of circumstance may be critical because the parties’ such arrangements of performance and counter-performance would not have been agreed upon had the new circumstance been presented at the time of the conclusion. In other words, the risks relevant to the critical change of circumstance were unforeseen and not considered by the parties when they mutually made prospective risk allocations in concluding a contract. As Article 6.2.2 of the UNIDROIT Principles states, the unexpected new circumstance fundamentally alters the original contractual equilibrium ‘either because the cost of a party’s performance has increased or because the value of the performance a party receives has diminished’. In other words, the increased burden that the debtor incurs or the diminished value of performance that the creditor receives due to the change of circumstances disrupts the contractual equilibrium; therefore, it is unfair for the adversely affected party to be bound by the contract after the changed circumstances. Renegotiation (based on party autonomy) and judicial relief (based on judicial intervention), if renegotiation fails, are thus required to restore contractual equilibrium. Hence, the contractual equilibrium theory can be understood as the second limb of the theoretical basis for the doctrine of change of circumstances.Table 1 Different Impacts of Unexpected Circumstances on Contract PerformanceUnexpected Circumstances Impacts on Performance Legal Consequences Examples in the Chinese Civil Code Force majeure Impossibility of performance Non-performance excused Art. 590 Force majeure Frustration of the purpose of the contract Termination of contract Art. 563(1) Change of circumstances Disruption of contractual equilibrium Renegotiation; termination or modification of contract Art. 533 -

3 Chinese Judicial Practice in Applying the Doctrine of Change of Circumstances

In general, China unequivocally confirms the principle of sanctity of contract by providing that ‘A contract entered into in accordance with the law shall be legally binding upon the parties to the contract’ in Article 119 of the Civil Code. Meanwhile, it recognises three doctrines of unexpected circumstances (see Table 1). To give a brief historical review, the doctrine of change of circumstances was formally transplanted from German law into Chinese law in 200919x Before the Contract Law Judicial Interpretation II was issued, Chinese courts had used and applied the doctrine of change of circumstances on the ground of the principle of fairness in judicial practice (e.g. Shandong Shenglong Zhiye Jituan Co. Ltd. v. Liu [2006] 莱阳民一初字第76号). The 1992 SPC’s Reply to the Application of Law Inquiry regarding a Technology Transfer Contract and Sale of Gasometer Components Dispute of Wuhanshi Meiqi Co. v. Chongqing Jianche Yibaiochang Meiqibiao Zhuangpeixian (最高人民法院关于武汉市煤气公司诉重庆检测仪表厂煤气表装配线技术转让合同购销煤气表散件合同纠纷一案适用法律问题的函) instructed lower courts to address change of circumstances according to the principle of fairness. This view was reconfirmed by the SPC in the1993 Minutes of the Meeting on the National Work of Adjudicating Commercial Cases (全国经济审判工作座谈会纪要) and the 2003 Notice on the Adjudication and Enforcement Work during SARS epidemic. Also see, H. Qiang, ‘Categorization Study of the Doctrine of Change of Circumstances’ (情势变更原则的类型化研究), 4 Legal Studies (法学研究) 57, at 58 (2010); also see C. Shouye, ‘The Understanding and Application of the Issue of Change of Circumstances under Interpretation II’ (最高人民法院关于适用《中华人民共和国合同法》若干问题的解释(二)之情势变更问题的理解与适用), 281 Law Application (法律适用) 44, at 45 (2009). through Article 2620x Art. 26 of the Contract Law Judicial Interpretation II provided: ‘Where any significant change of objective circumstances, which is unforeseeable at the time of concluding a contract and is neither commercial risk nor force majeure, occurs after the conclusion of the contract if to continue the performance of the contract is obviously unfair to one party or cannot fulfil the purposes of the contract and the party files a request for modification or termination of the contract with the people’s court, the people’s court shall decide whether to modify or terminate the contract in accordance with the principle of fairness and in light of the actual circumstances of the case’. (The italic parts were either revised or deleted by Art. 533 of the Civil Code.) of the Judicial Interpretation II of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) of Several Issues concerning the Application of Contract Law of People’s Republic of China (Contract Law Judicial Interpretation II).21x The Judicial Interpretation II of the SPC of Several Issues concerning the Application of Contract Law of the People’s Republic of China (最高人民法院关于适用《中华人民共和国合同法》若干问题的解释(二)) (promulgated by the SPC on 24 April 2009; effective on 13 May 2009; ineffective on 1 January 2021). In 2020, the Civil Code incorporated this doctrine with revisions into Article 533:

After a contract is formed, where a fundamental condition upon which the contract is concluded is significantly changed, which is unforeseeable by the parties upon conclusion of the contract and which is not one of the commercial risks, if continuing performance of the contract is obviously unfair to one of the parties, the adversely affected party may re-negotiate with the other party. Where agreement cannot be reached within a reasonable period of time, the party may request the people’s court or an arbitration institution to modify or terminate the contract.

The court or an arbitration institution shall, taking account of the actual circumstances of the case, modify or terminate the contract in compliance with the principle of fairness.22x The italic parts were either newly revised or added by Art. 533 of the Civil Code, compared to the previous provision in Art. 26 of the Contract Law Judicial Interpretation II.Five differences between Article 533 of the Civil Code and Article 26 of the Contract Law Judicial Interpretation II are as follows. First, a significant change of ‘objective circumstances’ was revised to a significant change to ‘a fundamental condition upon which the contract is concluded’, which clearly reflects the shared assumption theory as a theoretical basis of the doctrine of change of circumstances in Chinese law. Second, force majeure is no longer excluded from the scope of unexpected circumstances that may trigger the application of the doctrine of change of circumstances. As a matter of fact, Chinese courts deliberately ignored such exclusion and applied the doctrine of change of circumstances to a force majeure event that caused obvious unfairness to continue performance before Article 533 of the Civil Code was made.23x The SPC’s gazette case Chengdu Pengwei Shiye Youxian Gongsi v. Jiangxisheng Yongxiuxian Renmin Zhengfu and Yongxiuxian Boyanghu Caisha Guanli Gongzuo Lingdao Xiaozu Bangongshi (2011)民再字第2号 is an example. This case will be discussed in detail in Section 3.1. Third, the situation that an unexpected circumstance frustrates the purposes of the contract was removed from Article 533 of the Civil Code; therefore, the application scope of the doctrine of change of circumstances is appropriately and neatly narrowed down to the cases where an unexpected circumstance disrupts the contractual equilibrium. This revision confirms the contractual equilibrium theory as the second limb of the theoretical basis of the Chinese doctrine of change of circumstances. Fourth, the parties are required to renegotiate before resorting to judicial intervention. Finally, the parties may resort to an arbitration institution to solve a dispute concerning the doctrine when they have included an arbitration agreement in their contract.

Moreover, Article 32 of the Judicial Interpretation of the SPC of Several Issues concerning the Application of Title One General Provisions of Book Three Contracts of the Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China (Judicial Interpretation of the Book on Contracts)24x The Judicial Interpretation of the SPC of Several Issues concerning the Application of Title One General Provisions of Book Three Contracts of the Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China (最高人民法院关于适用《中华人民共和国民法典》合同编通则若干问题的解释) (promulgated by the SPC on 4 December 2023; effective on 5 December 2023). further explains some practical issues regarding the application of the doctrine of change of circumstances, which will be addressed in the relevant discussions in this section. Article 32 of the Judicial Interpretation of the Book on Contracts provides:Where, after the formation of a contract, policy changes, abnormal changes in market supply and demand, or any other factor result in price fluctuation unforeseeable by the parties at the time of conclusion and other than commercial risk, rendering it obviously unfair for a party to continue performing the contract, the people’s court shall determine that the fundamental conditions of the contract have undergone a ‘significant change’ as specified in paragraph 1 of Article 533 of the Civil Code unless the contract is related to commodities in an active market whose price is subject to long-term considerable fluctuation and risky investment financial products such as stocks and futures.

When the fundamental conditions of the contract have undergone significant changes as specified in paragraph 1 of Article 533 of the Civil Code, if the parties request a modification of the contract, the people’s court shall not terminate the contract; also, if a party requests modification while the other party seeks termination, the people’s court shall render a judgment to modify or terminate the contract based on the actual circumstances of the case and under the principle of fairness.

The people’s court shall, in entering a judgment to modify or terminate the contract according to Article 533 of the Civil Code, consider factors such as the time when the fundamental conditions of the contract undergo significant changes, the renegotiation between the parties and the losses caused to the parties by the modification or termination of the contract and specify the time of modification or termination of the contract in the decision.

Where the parties agree in advance to exclude the application of Article 533 of the Civil Code, the people’s court shall determine the agreement invalid.To investigate how Chinese courts judge an unexpected circumstance that has disrupted the contractual equilibrium and how they restore it by applying the doctrine of change of circumstances, this section of the article probes into relevant judicial decisions to reveal Chinese judicial approaches. The author started this study in 2019 by searching the PKULAW case database25x The PKULAW is a commonly used database in China. It includes, but not limited to, a statute database and a case database. The latter mainly retrieves judicial decisions from the SPC’s official online database called ‘China Judgements Online’ (中国裁判文书网, https://wenshu.court.gov.cn). and found 5,391 cases decided according to Article 26 of the Contract Law Judicial Interpretation II or Article 533 of the Civil Code as of 30 April 2023.26x Although the SPC required lower courts to publish judgments from 1 January 2014 (see the Provisions of the SPC on Online Publication of Judgments by the People’s Courts (最高人民法院关于人民法院在互联网公布裁判文书的规定; promulgated by the SPC on 21 November 2013 and effective on 1 January 2014), it has regularly selected and issued some cases of guidance value in its gazettes since 1985. This study also includes the relevant gazette and typical cases published before 1 January 2014. These decisions included (but were not limited to) the gazette and typical cases, but none of the guiding cases was concerned with the doctrine of change of circumstances. In total, 21 decisions were made by the SPC, and 142 decisions were made by the provincial high people’s courts. After reading all the high-level courts’ decisions and the lower courts’ judgements (because 97% of the cases regarding the doctrine of change of circumstances could not reach the provincial court or above and were adjudicated by lower courts), the author selected representative cases to be referred to as examples in the article and chose the high-level courts’ representative decisions as a priority, in order to discuss them in detail in the main text.

3.1 The Existence of Change of Circumstances and ‘Shared Assumptions’

3.1.1 The Doctrinal Distinction between a Change of Circumstance and a Commercial Risk

Article 533 of the Civil Code defines a ‘change of circumstance’ as an unforeseeable significant post-conclusion change to a fundamental condition upon which the contract is concluded (i.e. the foundation of the contract) but not a commercial risk. The SPC instructed the lower courts that ‘commercial risk’ refers to the risk inherent in carrying out a particular business activity.27x See Art. 3 of the Guiding Opinions of the SPC on Several Issues concerning the Trial of Civil and Commercial Contracts Disputes under the Current Situation (关于当前形势下审理民商事合同纠纷案件若干问题的指导意见) (promulgated by the SPC on 7 July 2009; effective on the same day). Chinese courts see a ‘commercial risk’ as a foreseeable common risk in doing business, whose materialisation may ‘adversely influence or frustrate a party’s assumption about the profitability of transactions’,28x See Xinxiangshi Muyequ Gongxiao Hezuoshe Diyi Fenshe v. Li Xiangdong(2015) 新中民五终字第205号. such as changes in the market supply-demand conditions,29x See Li v. Jin (2015) 兴民终字第517号; Song v. Qiao (2017) 豫0102民初4565号; Wuchengxian Shuili Gongcheng Co. Ltd. v. Xu Baozong (2018) 鲁1428民初975号; Chen Faming v. Chen Qingbin (2017) 闽0781民初1310号; Putianshi Xinhuadu Wanjiahui Gouwu Guangchang Co. Ltd. v. Huang Zhiguang (2014) 涵民初字第3597号; Chen v. Kelamayi Shi Yangguang Shidai Jingying Guanli Co. Ltd. (2018) 新民申1128号. real estate property prices30x See Liu v. Chen, Zhang and Huai’an Wanqi Zhiye Co. Ltd. (2017) 苏民终1091号; Dong v. Zhao (2016) 苏0106民初4882号; Hebei Shuhong Fangdichan Kaifa Co. Ltd. v. Hengshuishi Tiaochengqu Hejiazhuangxiang Songjiacun Cunmin Weiyuanhui (2017) 冀1102民初2363号. or rental prices,31x See Tianjinshi Beichengqu Dazhangzhuangzhen Dayangzhuang Cunmin Weiyuanhui v. Tianjinshi Huaxing Zhisuo Chang and Wen Zhonghua (2017) 津01民终4828号; Tumenheshige and Others v. Li Chunguo (2015) 赤民一终字第1451; Zhang v. Xingyangshi Gaoshanzhen Panyaocun Cunmin Weiyuanhui (2016) 豫0182民初1981号. However, it is noteworthy that Art. 214 of the CCL limits the maximum lease term to twenty years. commodity prices,32x See Liu Xiulan v. Fuguxian Ruifeng Meikuang Co. Ltd. (2016) 最高法民终342号. consumption values,33x See Lidu Zhengxing Meirong Yiyuan Gufen Co. Ltd. v. Jiangyin Ganghong Huagong Xiaoshou Co. Ltd. (2017) 苏02民终5193号. as well as tax adjustment.34x See Daqing Chuangye Guangchang Youxian Zeren Gongsi v. Shenyang Jiti Lianshe Qiye (Jituan) Co. Ltd. (2016) 最高法民申2594号; Zhai and Meng v. Zhongguo Guangda Yinhang Gufen Co. Ltd. Daqing Fenhang (2017) 黑06民终1716号. Despite an association with the foundation of the contract, commercial risk brings about a change that remains within a normal range.35x See Sichuan Yuanhe Jianshe Gongcheng Co. Ltd. v. Li Sanxing and Others (2016) 川13民终652号. Article 32(1) of the Judicial Interpretation of the Book on Contracts illustrates an example of commercial risk – ‘commodities in an active market whose price is subject to long-term considerable fluctuation and risky investment financial products such as stocks and futures’.

In contrast, the SPC explains that ‘change of circumstances’ refers to unforeseeable, non-inherent and abnormal change of the circumstances constituting the foundation of a contract.36x See n. 27 above. They include extraordinary changes in economic conditions or government policy changes, war, natural disaster, strike, financial crisis or sharp currency exchange rate changes.37x See Changsha Baimaqiao Jianzhu Co. Ltd. v. Binzhoushi Yuxing Fangdichan Kaifa Co. Ltd. (2015) 湘高法民一终字第68号; Suqianshi Suchengqu Guoyou Linchang v. Chen Xuemei (2015) 宿中民初字第00061号; Shanghai Xiangsheng Siliao Co. Ltd. v. Huarun Xuehua Pijiu (Shanghai) Co. Ltd. (2016) 沪0113民初13882号; Various Groups of Jinxixian Duiqiaozhen Hengyuan Cunmin Weiyuanhui v. Jinxixian Duiqiaozhen Tianzike Cunmin Weiyuanhui (2016) 赣1027民初24号; Xingjiang Bazhou Wanfang Wuzi Chanye Co. Ltd. v. Xinjiang Nafu Fangdicahn Kaifa Co. Ltd. (2016) 新民终726号. As Article 32(1) of the Judicial Interpretation of the Book on Contracts illustrates, policy changes and abnormal changes in market supply and demand that resulted in price fluctuation unforeseeable by the parties at the time of conclusion can be regarded as changes of circumstances.

For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, in the Guiding Opinions on Several Issues of Properly Adjudicating Civil Cases concerning the COVID-19 Pandemic I and II,38x The Guiding Opinions on Several Issues of Properly Adjudicating Civil Cases concerning the COVID-19 Pandemic I and II (关于依法妥善审理涉新冠肺炎疫情民事案件若干问题的指导意见(一)(二)) (promulgated by the SPC on 16 April and 15 May 2020, respectively). the SPC recognised the COVID-19 outbreak might amount to a change of circumstance and instructed lower courts to make appropriate adaptions (including changing the performance period, performance method or price of the contract) to sale contracts, lease agreements, offline training contracts and personal loan contracts on a case-by-case basis.3.1.2 Contractual Construction about the Risk Allocation Regarding the Changed Circumstance

To determine the existence of a change of circumstances, Chinese courts start with the relevant contract terms to construe the risk allocation by the parties.39x Also see Keshi Huisen Wuliu Co. Ltd. v. Xinjiang Qilu Gangjiegou Caiban Co. Ltd. (2023) 新民申1297号. For example, in An v. Shao,40x (2017) 最高法民再26号. the parties signed a contract in May 2006. Because the seller, Shao, was bound not to pay off her loan before the repayment day under her mortgage contract with the bank, the sale of the property could not be executed at the time of or immediately after the conclusion. They thus agreed that the buyer, An, rent the property for a term of four years (from 1 July 2006), and Shao must sell the property to An for RMB 608,000 on 1 July 2010. The property market price became RMB 2,548,555 four years later, increasing by more than three times the agreed price. Shao decided not to perform the contract. After An filed an action for breach of contract, Shao claimed a change of circumstances. The SPC retried this case and held that the contract concerned consisted of dual contractual relationships: lease and sale. The key issue was whether the increase in the property price was a commercial risk or a change of circumstance. It held that although the degree of the price increase might be beyond the parties’ expectations, it remained a commercial risk because they intended to make a sale of property transaction at the conclusion, which was deferred merely because the seller was bound to the repayment restriction under her own mortgage arrangement. In other words, the SPC constructed that the parties had mutually allocated the risk of the property price increase to the seller when concluding the contract.

When Chinese courts cannot decide whether the parties have allocated the risk of the unexpected circumstance by construction of contractual terms, they will consider which party the particular risk should be allocated to by considering various factors. Following the SPC’s guidance,41x See n. 27 above. Chinese courts consider the foreseeability and extent of the risk,42x See Shandong Binzhou Guanghe Mianye Co. Ltd. v. Binzhou Zhongfang Yintai Shiye Co. Ltd. (2016) 鲁1602民初2435号; Zhan v. Yiwushi Zaisheng Ziyuan Riyong Zapin Co. Ltd. (2014) 金义商初字第3690号. In Shanghai Shen Xinxing Muqiang Gongcheng Co. Ltd. v. Chongqing Yaopi Gongcheng Boli Co. Ltd. (2021) 沪0117民初18287号, the court held that the parties signed their contract over two months after the COVID-19 outbreak and they should foresee and consider the risk. the nature of the transaction and the specific conditions of the market,43x Regarding the varying business environment or market conditions, see Xinjiang Yili Nongchun Shangye Yinhang Co. Ltd. v. Li Xianjun and Li Yanran (2022) 新40民终391号. the characteristics of the party,44x When a land developer argued that the government restrictions on the property market were change of circumstances in the case of a granting land-use-right contract in Foshanshi Guotu Ziyuanju and Chengxiang Guihuaju v. Hengda Dichan Jituan Co. Ltd. and Foshanshi Nanhai Yingyu Fangdichan Fazhan Co. Ltd. (2015) 粤高法民一终字第86号, the High People’s Court of Guangdong Province disapproved because the defendants as experts should foresee the restrictions in the local city and they were seen as commercial risk. Also see Zhang, Chen and Yu v. Shirui (Beijing) Yiyuan Guanli Co. Ltd. (2018) 闽01民终10542号; Shenzhenshi Jinhui Qiye (Jituan) Co. Ltd. and Qiu v. Shenzhen Wanke Fazhan Co. Ltd. and others (2019) 最高法民终1748号. and the factor of imputability (i.e. whether the adversely affected party is at fault and responsible for the occurrence of a change of circumstances,45x See Wu and Wang v. Sanya Wenhao Lvye Co. Ltd. (2017) 最高法民申3380号; Zhang v. Ren (2016) 最高法民终781号. or the preventability and controllability of the risk).

The SPC’s guidance adds a new feature to the notion of change of circumstance – it must not be preventable or in control of the adversely affected party.46x See n. 27 above. This echoes the wording – ‘the events are beyond the control of the disadvantaged party’ – provided by Article 6.2.2 of the UNIDROIT Principles. Related to this, if comparing with Article 590(2) of the Civil Code, which disallows the adversely affected party to resort to the doctrine of force majeure for exemption of liability for breach of contract where the force majeure occurs after the party has delayed its performance, Article 533 of the Civil Code does not have an equivalent subsection. However, Chinese courts have addressed this statutory legal loophole by disallowing the adversely affected party to rely on the doctrine of change of circumstances if the changed circumstance occurs after its delayed performance. This is because the changed circumstance would not affect its performance at all had it not delayed its performance. In other words, the impact of the changed circumstance is preventable by the adversely affected party’s on-time performance. For example, in Chongqing Changhong Suliao Chang v. Chongqing Tianlong Fangdichan Kaifa Co. Ltd.,47x (2016)最高法民终203号. the parties signed a demolition and relocation contract in 2002. However, the defendant failed to pay the land-use fee of the relevant land in 2004; hence, the government did not grant it the land-use right. Although the government made an unexpected change to land planning of the relevant land in 2007, it happened after the defendant’s non-payment of the land-use fee. The SPC, therefore, held that the defendant could not rely on the doctrine of change of circumstances. Even before this case, lower courts had the same view that the doctrine should not apply to a case where a changed circumstance occurred after the obligor’s delayed performance.48x See Dandongshi Sanjiang Jingmao Co. Ltd. v. Qingdao Yongtai Jiaye Jingmao Co. Ltd. and Jingjiang Chuanwu Co. Ltd. (2015) 辽民三终字第193号; Chenzhoushi X Fangdichan Kaifa Co. Ltd. v. Sheng (2013) 郴苏民初字第1045号.3.1.3 Judicial Enquiry about the Shared Assumptions of the Parties

After finding an unforeseeable significant post-conclusion change, Chinese courts further enquire whether the changed circumstance contradicts the parties’ shared assumptions upon which their contract is based. Three cases decided by the high-level courts are helpful to illustrate this observation.

In the first case, Chengdu Pengwei Shiye Co. Ltd. v. Jiangxisheng Yongxiuxian Renmin Zhengfu and Yongxiuxian Boyanghu Caisha Guanli Gongzuo Lingdao Xiaozu Bangongshi,49x (2011) 民再字第2号. the plaintiff successfully bid for the right of sand excavation at four excavation points in the water areas (within Yongxiu County) of Boyang Lake from 10 May 2006 to 31 December 2006. However, from August 2006, the water level of Boyang Lake was at its lowest of the past 36 years, which made sand carriage extremely difficult, if not impossible, to reach the contracted excavation points. The plaintiff was forced to stop sand excavation and applied to the court to modify the contract according to Article 26 of the Contract Law Judicial Interpretation II. The SPC reasoned that the parties agreed on the contractual terms based on the normal water level at the plaintiff’s excavation points from early May to late October in the past, as stated in the defendant’s advertising announcement. In other words, the unforeseeable circumstance of the extraordinarily shallow water level occurring in August 2006 significantly contradicted what they assumed when prospectively calculating the plaintiff’s expected values and costs of performance.

In the second case, Jiangsu Zhengtong Hongtai Gufen Co. Ltd. v. Changzhou Xindong Huagong Fazhan Co. Ltd.,50x (2015) 民提字第39号. the defendant contracted desulphurisation services for its coal-burning boilers from the plaintiff in September 2011. Three months later, the Changzhou municipal government, in implementing the provincial government’s new environmental protection policy, required the defendant to demolish its coal-burning boilers by June 2012. The defendant requested to terminate the contract according to the doctrine of change of circumstances, but the plaintiff disagreed. The case ultimately reached the SPC. It reasoned that the local municipal government’s decision to demolish the defendant’s coal-burning boilers was an unforeseeable significant change in objective circumstances constituting the foundation of the contract. In other words, when concluding the contract, the parties shared the tacit assumption that the government would allow the use of coal-burning boilers during the contract term. The SPC found a change of circumstances in favour of the defendant.

In the third case, Henan Bilairui Jiaoyu Keji Co. Ltd. v. Zhengzhou Xiaoniudun Jiaoyu Keji Co. Ltd.,51x (2022) 豫知民终404号. the defendant signed a franchise agreement with the plaintiff, granting the latter to operate a business associated with its trademark ‘Little Newton’ to provide education services to little children from October 2020 to October 2022. The Central Government unexpectedly issued a so-called double-reduction of student burden policy in July 2021 to forbid any subject-related education or training services to preschool children. The franchisee claimed the new policy constituted a change of circumstance and requested the court to terminate the franchise agreement. The High Court of Henan Province reasoned that the parties shared the assumption that the State permitted subject-related education or training services offered to preschool children. The prohibition policy contradicted their shared assumption, and they could not prospectively allocate the risk at the time of the conclusion. Hence, the court ruled in favour of the franchisee in this case.52x C.f. in Xinjiang Chengshi Touzi Co. Ltd. v. Xinjiang Zhuoshi Kongjian Shangye Yunying Guanli Co. Ltd. (2023) 新民申30号, the High Court of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region held that the State’s ‘double reduction of student burden policy’ did not amount to a change of circumstance because the lease parties had no shared assumption that the premises concerned would be sublet to companies providing educational and training services.

By contrast, in Zhang v. Wang and Tian,53x (2016) 京03民终3339号. when a local government issued a new policy to control the local property market by disqualifying non-local citizens from owning real estate properties, the non-local-citizen seller argued that the policy amounted to a change of circumstances and rendered him unable to own a real estate property after selling the property to the defendant. Thus, the seller requested the court terminate the sale contract by invoking the doctrine of change of circumstances. However, the No.3 Intermediate Court of Beijing rejected the seller’s argument because the contracting parties did not share the assumption that the seller would still be qualified to own a new real estate property after their transaction.54x The same ruling was also found in Liu v. Yin (2016) 苏0583民初16813号.3.2 The Impact of Change of Circumstances and ‘Contractual Equilibrium’

As the SPC insightfully stated in Huarui Fengdian Keji (Jituan) Gufen Co. Ltd. v. Zhaoyuan Xinlong Shunde Fengli Fadian Co. Ltd.,55x (2015) 民二终字第88号. the doctrine of change of circumstances applied ‘only when the foundation of a contract was weakened or collapsed due to an event not imputable to the parties and, as a result, contractual equilibrium was destroyed to such an extent that to continue the performance would violate the principle of fairness’.56x This implies that causation between the occurrence of a change of circumstance and the disruption of contractual equilibrium is required to revoke the doctrine of change of circumstances, which was confirmed by the High Court of Beijing in Beijing Branch of Shanghai Pudong Fazhan Yinhang Co. Ltd. v. Beijing Guotou Gonglu Jianshe Fazhan Co. Ltd. (2022)京民终427号. Despite the silence of Article 533 of the Civil Code regarding different impact scenarios, based on the investigation of a large number of the relevant judicial decisions, it is observed that Chinese courts have presented three categories where the contractual equilibrium between the parties is disrupted.

3.2.1 Sharply Increased Costs of the Performance (Hardship in Performance)

A change of circumstance may cause the performance of the obligations excessively onerous. For example, in Shanghai X Fangdichan Jingying Co. Ltd. v. Huang,57x (2013) 闸民三(民)初字第1744号. the parties signed a pre-sale of real property contract in March 2011 and agreed that the payment of the property price must be made by 23 June 2011. The defendant buyer failed to obtain a mortgage loan of RMB 3.54 million from the bank by the deadline due to an unexpected change in the government’s mortgage loan policy that aimed to curb the soaring property market. The Basic People’s Court of Zhabei District of Shanghai ruled that the change in the government’s mortgage loan policy constituted a change of circumstance and rendered the buyer’s performance extraordinarily difficult. To continue the performance would be highly unfair to him in such a difficult situation. The court thus modified the contract term by extending the payment deadline three months from the judgment date.

An unforeseeable sharp tax increase may cause the performance to be excessively onerous. For example, in Shandong Binzhou Guanghe Mianye Co. Ltd. v. Binzhou Zhongfang Yintai Shiye Co. Ltd.,58x (2016) 鲁1602民初2435号. the parties made a warehouse lease contract for a term of twenty years in 2003. The area of the rented premises was 42,933.55 square metres, and the monthly rental was RMB 250,000. However, the government gradually increased the land-use tax from RMB 2 per square meter in 2002 to RMB 12 per square metre in 2014, increasing by five times. The landlord had to pay the significantly increased tax, which exceeded the rental it received from the defendant tenant. In other words, the landlord could not afford the performance under the agreed rental after the sharp tax increase. Thus, the landlord claimed a change of circumstance and applied for termination of the contract. The Basic People’s Court of Binzhou District of Binzhou City of Shandong Province held that the tax increase was beyond the foreseeability of the parties at the time of the conclusion and amounted to a change of circumstances. The court held that continuing the performance would be obviously unfair to the landlord plaintiff.3.2.2 Diminished Value of the Received Performance

The value that the creditor receives from the performance excessively decreases due to a change of circumstances despite the performance costs of both parties being unchanged. Chengdu Pengwei Shiye Co. Ltd. v. Jiangxisheng Yongxiuxian Renmin Zhengfu and Yongxiuxian Boyanghu Caisha Guanli Gongzuo Lingdao Xiaozu Bangongshi59x See n. 49 above. presents another example. In this case, the water level of Boyang Lake became extremely low in August 2006. Although the plaintiff had paid for a licence of sand excavation at four agreed excavation points, because of the low water level, it could not practically afford the high expenses of sand carriage to reach the excavation points. This meant it gained much less than expected from sand excavation at the four excavation points. Given a disturbance of the equilibrium between the value of the performance that the plaintiff received and its consideration for the performance (i.e. the licence fee paid), the SPC ruled that to continue the performance would be obviously unfair to the plaintiff and, therefore, ordered the licence fee to be reduced according to the actual gains that the plaintiff received.60x Similar cases include Jiangxi Aoyang Shengtai Nonglin Fazhan Co. Ltd. v. Boyangxian Bintian Shuiku Guanliju (2017) 赣1128民初639号; Zhang v. Lu and Sanya Sanling Mangguo Zhongzhi Co. Ltd. (2016) 琼0271民初1114号.

In Kaifengshi Xinghe Jingying Fuwu Co. Ltd. v. Kaifeng Sanmao Wenhua Shiye Co. Ltd.,61x (2015) 豫法民三终字第00023号. the parties made a lease contract in December 2009. They agreed that the defendant rented a building in Drum Tower Square of Kaifeng City for commercial purposes from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2015. However, in 2012, the municipal government started construction projects at Drum Tower Square, which caused the main entrance to the building to be closed from April 2012 to October 2013. The High People’s Court of Henan Province held that the construction projects started by the local government amounted to a change of circumstances. Although the plaintiff landlord had already performed his obligation under the contract, the business values of the defendant tenant in operating the commercial building were significantly reduced by the change of circumstances. Requiring paying the agreed rental amount would cause obvious unfairness to the defendant tenant. Therefore, the court decided to reduce the payable rental to 20% of the original amount during the affected period.

In another case, Jiuquanshi Diyi Zhongxue v. Liu and Zhang,62x (2016) 甘09民终170号. the plaintiff was a secondary school, and it made a six-year lease contract with the defendant in August 2008. The parties agreed that the premises would be used as commercial billiard rooms and a skating rink. However, the local education bureau later closed all commercial billiard rooms and internet bars near schools. The Intermediate People’s Court of Jiuquan City of Gansu Province agreed that the local education bureau’s decision constituted a change of circumstances and caused the defendant’s use of the premises to be substantially affected. Therefore, the contract was held to be terminated according to the doctrine of change of circumstances. These decisions echo the SPC’s view that ‘obvious unfairness’ is evident when the performance values of a party are significantly lower than its performance costs.63x See Wu and Wang v. Sanya Wenhao Lvye Co. Ltd. (2017) 最高法民申3380号.3.2.3 A Sharp Increase in the Value of the Received Performance

Due to a change of circumstance, the value of the received performance may become excessively higher than the parties expected at the conclusion. Such a case of the disrupted contractual equilibrium often occurs in a long-term contract of land-use right. For example, in Botoushi Wangwuzhen Qianyangquancun Cunmin Weiyuanhui v. Tang Peide,64x (2018) 冀09民终5998号. the parties signed a management of land contract65x In Chinese law, management of land contract (土地承包经营合同) is a special contract where the collective owner of rural land grants the land-use right of a plot of land to the land user in return for the land-use fees. It is usually a long-term contract. Under such a contract, the land user’s right is a quasi-property right and can be transferred in a free market. for a term of 25 years at the price of RMB 175 per mou66x Mou (亩), a Chinese unit of area, equivalent to about 670 square metres. per year in 2002. The State cancelled the agriculture tax in 2004. It has further provided agriculture subsidies to farmers since 2007, with the amount of the subsidy increasing year by year. Due to such a change of the State policy on agricultural production, the defendant not only used the land for free but also obtained a surplus from receiving the government subsidy minus the paid land management fee. The Intermediate People’s Court of the Cangzhou City of Hebei Province held that the State’s policy to encourage agricultural production through the cancellation of tax and the provision of government subsidy constituted a change of circumstances, which caused the market price for management of land to increase to RMB 650 per mou per year in 2016 (about 2.7 times of the agreed price). Because continuing the performance of the contract was obviously unfair to the plaintiff landowner, the court ordered the defendant to pay the plaintiff the land management fee at the price of RMB 650 per mou per year from 2017.67x Similar cases include Chongqingshi Shapingbaqu Fenghuangzhen Wufucun Qianniufangzishe v. Zhang Yi (2014) 渝一中法民终字第04136号; Shenzhoushi Chenshizhen Xizhoubaocun Cunmin Weiyuanhui v. Liu Changfu (2016) 冀1182民初614号; Haiyanxian Shendangzhen Zhongqiancun Di Sanshiyi Cunmin Xiaozu v. Yu Zhangsheng and Yu Yaping (2015) 嘉盐沈民初字第238号; Song v. Xia (2015) 克民初字第3181号; c.f. Xiang v. Wang (2016) 吉0702民初3359号; Xi’anshi Chang’anqu Xiliu Jiedao Puyangcun Xizu v. Jin Wusheng (2017) 陕0116民初6207号; Xu Kecun v. Zaozhuangshi Yichengqu Yinpingzhen Xibaishancun Cunmin Weiy (2016) 鲁民申166号.

The same may happen to a transfer of land-use-right contract.68x See Wei v. Zhang (2015) 州丰民初字第30号. In Xu v. Wang,69x (2015) 木民初字第187号. the parties entered into an agreement in 2006, under which Xu transferred to Wang the right to land use of a 50-mou rural land for a term of 21 years, at a lump sum price of RMB 63,000 (i.e. the transfer fee was RMB 60 per mou per year). They also agreed that Wang would fulfil the requirements of grain yields to the government, but he was entitled to receive any government subsidies. The State has increased government subsidies to farmers since 2013, at RMB 79.53 per mou per year for 2013/14. The Basic People’s Court of Mulan County of Ha’erbin City of Heilongjiang Province held that the State policy to increase government subsidies to farmers amounted to a change of circumstance, which made Wang have a surplus of RMB 19.53 per mou per year after a deduction of the paid transfer fee. It ruled that continuing the performance would result in obvious unfairness to Xu and, therefore, ordered to terminate the contract. -

4 Analysis of Chinese Judicial Approaches and the Comparative Law Implications

4.1 Three-Step Analytical Framework of Chinese Courts

Although Article 533 of the Civil Code does not explicitly use the terms ‘shared assumptions’ and ‘contractual equilibrium’, as drawn from Chinese judicial decisions illustrated in Section 3, the courts have adopted the following three-step analytical framework in applying Article 533 in judicial practice, by incorporating the above two-limb theoretical basis:

(1) Through contractual construction, to decide whether the adversely affected party has assumed the risk of the alleged change of circumstance;

(2) If not, then to consider whether the alleged change of circumstance goes beyond or contradicts the parties’ shared assumptions on which their contract is based; and

(3) If the answer is positive, finally to determine whether and to what extent the alleged change of circumstance disrupts the contractual equilibrium.Compared to the language of Article 533 of the Civil Code, the three-step judicial approach demonstrates its advantages in three aspects. First, the approach clarifies that the starting point of applying the doctrine of change of circumstances is a contractual construction of the parties’ intention on the risk allocation regarding the risk of the changed circumstance. When the parties have allocated the risk to one party at the time of concluding their contract (as the case An v. Shao70x See n. 40 above. shows), the court must respect party autonomy and endorse what the parties have agreed on regarding the risk allocation. In other words, there is no space for the court to apply the doctrine in such situations.

This first analytical step that Chinese courts adopt echoes the requirement that ‘the risk of the events was not assumed by the disadvantaged party’ set out in Article 6.2.2 of the UNIDROIT Principles as well as the U.S. case Transatlantic Financing Corp. v. United States.71x 363 F.2d 312 (D.C. Cir. 1966). In that case, the plaintiff incurred additional costs of taking a longer route through the Cape of Good Hope after the shorter route through the Suez Canal was impossible due to the unexpected armed conflict and then claimed to recover the additional costs by relying on the doctrine of impossibility of performance. After confirming that the closure of the Suez Canal was unexpected, the court enquired whether the risk of the unexpected occurrence had been allocated either by expressed or implied agreement or by custom. It concluded that ‘[i]f anything, the circumstances surrounding this contract indicate that the risk of the Canal’s closure may be deemed to have been allocated to Transatlantic’ from its observation that ‘[n]o doubt the tension affected freight rates’. In other words, the implied allocation of the risk of the closure of the Suez Canal was impounded by the price.72x Eisenberg, above n. 10, at 221.

Regarding the second analytical step, the Chinese courts considered the parties’ shared assumptions on which their contract is based in individual cases even before the wording ‘a fundamental condition upon which the contract is concluded’ was added to Article 533 of the Civil Code.73x Art. 26 of the Contract Law Judicial Interpretation II did not include such wording. In practice, judges translate ‘a fundamental condition upon which the contract is concluded’ to an enquiry about the shared assumption on which the contract is based. This approach is methodically ascertainable and practically more convenient than the vague concept of ‘the fundamental condition’ or ‘the root of the contract’. In their analysis, the courts asked whether the shared assumption is decisive in terms of the parties’ willingness to make a contract (such as in the case Jiangsu Zhengtong Hongtai Gufen Co. Ltd. v. Changzhou Xindong Huagong Fazhan Co. Ltd.74x See n. 50 above.) or whether the shared assumption is determinant regarding the specific primary rights and obligations that they bargained (such as in the case Chengdu Pengwei Shiye Co. Ltd. v. Jiangxisheng Yongxiuxian Renmin Zhengfu and Yongxiuxian Boyanghu Caisha Guanli Gongzuo Lingdao Xiaozu Bangongshi,75x See n. 49 above. where the court linked the shared assumption about the normal water level of Boyang Lake to the plaintiff’s price for the right of sand excavation payable to the defendant).

Finally, the general principle of fairness (as codified in Art. 6 of the Civil Code) can be seen as the underlying rationale for the doctrine of change of circumstances in Chinese law. This is evidenced by the wording – ‘if continuing performance of the contract is obviously unfair to one of the parties’ – of Article 533 of the Civil Code. The principle of fairness, on the one hand, justifies judicial relief in the cases of change of circumstances and shows such cases involve a legal judgment in the name of ‘fairness’; on the other hand, the principle of fairness appears vague and equivocal, leaving great discretion to the judiciary. Hence, the third analytical step adopted by Chinese courts remedies the ambiguous criteria – ‘if continuing performance of the contract is obviously unfair to one of the parties’ – by asking whether and to what extent the alleged change of circumstance disrupts the contractual equilibrium. It is observed that Chinese judicial decisions on change of circumstance are all concerned with bilateral contracts, where both parties are a promisor to perform and, meanwhile, a promisee to receive counter-performance, as the issue of contractual equilibrium is relevant only to bilateral contracts. Chinese courts often interpret ‘contractual equilibrium disturbed by a change of circumstance’ as follows: ‘an imbalance between the contractual rights and obligations of a party’, ‘an imbalance of the consideration relationship’ or ‘a distortion of equivalence of exchanges’.76x See Shangzhou Wujin Wanda Guangchang Touzi Co. Ltd. v. Xia Lu (2018) 苏04民终1789号. The Chinese judicial wisdom about specific categories of contractual equilibrium is to be assessed in the next session.4.2 Judicial Categorisation of Disrupted Contractual Equilibrium

As presented in Section 3, Chinese courts recognised three categories of contractual equilibrium that a change of circumstance may disrupt: (1) sharply increased costs of the performance (hardship in performance); (2) diminished value of the received performance; and (3) a sharp increase in the value of the received performance. This section presents the comparative law analysis of each category and their implications for defining the relationships between the three doctrines regarding unexpected circumstances (i.e. the doctrine of change of circumstances, the doctrine of frustration of the purpose of the contract and the doctrine of force majeure) under Chinese contract law.

The most common scenario of the disrupted contractual equilibrium is hardship in performance, which explains why the doctrine of change of circumstances is also termed ‘the doctrine of hardship’. In the comparative law discourse, the doctrine of change of circumstances is often discussed along with the common law doctrine of frustration. However, it is essential to note that the focus of the common law doctrine of frustration is the nature of the bargain made by the parties.77x Loke, above n. 2, at 6. When the performance in an unexpected circumstance becomes ‘a fundamentally different obligation’ (i.e. different in kind) from what the parties undertook when the contract was made, the contract may be discharged. Moreover, ‘an increase of expense is not a ground of frustration,’ although it may cause the adversely affected party’s profit to be reduced or even disappear.78x Tsakiroglou & Co Ltd. v. Noblee Thorl GmbH [1962] AC 93. By contrast, the doctrine of change of circumstances focuses on the balance of the bargain, that is, a contractual equilibrium between the rights and obligations that the parties reached based on their shared assumption at the time of the conclusion. An unexpected circumstance significantly changed the shared assumption, thus causing the performance to be excessively onerous (i.e. hardship in performance) and rendering it unfair for the adversely affected party to enforce the performance. Therefore, the common law doctrine of frustration aims to release the parties from a radically different bargain they undertook, while the doctrine of change of circumstances seeks to save the adversely affected party from an onerous performance the adversely affected party has not undertaken. Unfortunately, such distinct focus between these two doctrines has often been overlooked in the literature,79x For example, Chen, above n. 2. although they both serve to respect and honour the true intentions of the parties and promote party autonomy.

The second category of disrupted contractual equilibrium that Chinese courts recognise involves the diminished value of the performance received by the adversely affected party. This echoes the definition of hardship set out in Article 6.2.2 of the UNIDROIT Principles. Unlike the first category, which focuses on the obligor who is to perform its obligation, the second category focuses on the creditor who will receive the performance despite the obligor’s expense of performance remaining the same and possible. The decrease in the value of the received performance is a matter of degree. When the diminished value is unbalanced with the consideration the creditor has provided, the bargained contractual equilibrium is disrupted. In this case, the court may consider reducing the consideration pro rata, as the SPC did in Chengdu Pengwei Shiye Co. Ltd. v. Jiangxisheng Yongxiuxian Renmin Zhengfu and Yongxiuxian Boyanghu Caisha Guanli Gongzuo Lingdao Xiaozu Bangongshi.80x See n. 49 above.

It is worth noting that ‘the value of the received performance’ often links to the purpose of the contract; hence, when an unexpected circumstance diminishes the value of the received performance to a critical point, it is likely to frustrate the purpose of the contract, thus concurrently triggering the doctrine of frustration of the purpose of the contract under Article 563(1) of the Civil Code. In that situation, both the doctrine of change of circumstances (Art. 533) and the doctrine of frustration of the purpose of the contract (Art. 563[1]) may become applicable to the second category of the disrupted contractual equilibrium. It is up to the adversely affected party to decide which doctrine to invoke to suit their interests better. Jiangsu Zhengtong Hongtai Gufen Co. Ltd. v. Changzhou Xindong Huagong Fazhan Co. Ltd.81x (2015) 民提字第39号. is a good example.82x Similar cases include Taiyuan Meikang Peixun Xuexiao v. Shanxi Jinxin Tongda Wuye Guanli Co. Ltd. (2022) 晋民申4577号, where in August 2020 the tenant terminated a lease contract by notification based on the doctrine of frustration of the purpose of the contract because the ‘double-reduction of student burden policy’ and the COVID-19 pandemic combined to frustrate the purpose of the lease (i.e. being used for its education service business). The lower courts endorsed the termination based on the doctrine of change of circumstances. The High Court of Shanxi Province confirmed the applicability of Art. 533 of the Civil Code to this case. In this case, the local government’s decision to require the defendant to demolish its coal-burning boilers within six months rendered the plaintiff’s performance (i.e. desulphurising the coal-burning boilers) valueless to the defendant. The SPC supported the defendant’s request to terminate the contract based on the doctrine of change of circumstances. In law, the defendant could also alternatively terminate the contract by a notification sent to the other party according to the doctrine of frustration of the purpose of the contract under Article 94(1) of the Contract Law83x The Contract Law (合同法) (promulgated by the National People’s Congress on 15 March 1999, effective 1 October 1999, invalid 1 January 2021). (the equivalent to Art. 563[1] of the Civil Code).

Next, from the comparative law perspective, the third category of the disrupted contractual equilibrium recognised by the Chinese judiciary is a scenario not illustrated by Article 6.2.2 of the UNIDROIT Principles. The judicial decisions that fall under the third category were all concerned with long-term contracts and involved radical government policy changes that resulted in the received performance yielding a surplus or windfall after deducting the consideration the creditor paid. Hence, the obligator argued the bargained contractual equilibrium was disrupted consequently and thus requested judicial intervention to restore it. In the author’s view, the Chinese courts were willing to grant judicial relief to the adversely affected party not only because the balance between the creditor’s rights and obligations was distorted but also because the nature of the contract was changed from a bilateral contract to a unilateral or gratuitous contract by the unexpected changed circumstance. Although such cases may rarely happen, the third category of the disrupted contractual equilibrium that the Chinese courts recognise has contributed to the completeness of the contractual equilibrium theory for a comparative law discourse of the doctrine of change of circumstances.84x D. Girsberger and P. Zapolskis, ‘Fundamental Alteration of the Contractual Equilibrium under Hardship Exemption’, 19(1) Jurisprudence 121, at 134 (2012).

Importantly, the above three categories of disrupted contractual equilibrium delineated by Chinese courts help to clarify the relationships between the three doctrines regarding unexpected circumstances in the current Chinese law. In the past, Article 26 of the Contract Law Judicial Interpretation II was criticised for causing great confusion regarding the relationships of the three doctrines of unexpected circumstances because of two rules it provided: (1) ‘force majeure’ events were excluded from the scope of ‘change of circumstances’ and (2) the doctrine of change of circumstance might be applied to address the case of ‘frustration of the purposes of the contract’.85x Liu, above n. 2, at 80. Therefore, Article 533 of the Civil Code removes the confusion by deleting the above two rules and helps to establish clear and logical relationships between the three doctrines of unexpected circumstances under the Chinese contract law (see Figure 1). Despite the different functions the three doctrines are designed to play, their application scopes do overlap in some situations: (1) when an unexpected circumstance diminishes the value of the received performance to a critical extent that the purpose of the contract is frustrated, despite the possible performance, both the doctrine of change of circumstances and the doctrine of frustration of the purpose of the contract become applicable; (2) when an unexpected circumstance causes de facto or legal impossibility of performance and thus frustrates the purpose of the contract, both the doctrine of frustration of the purpose of the contract and the doctrine of force majeure may apply. It is for the claimant to consider and choose which legal basis better serves their interests.

A caveat is that while Article 563(1) of the Civil Code can also apply to cases involving the impossibility of performance caused by force majeure, the doctrine of change of circumstance under Article 533 no longer applies to such cases (as shown in Figure 1). This is because Article 533 of the Civil Code has deleted the wording ‘frustration of the purpose of the contract’, which previously existed in Article 26 of the Contract Law Judicial Interpretation II. As a result, Chinese courts previously terminating a contract in the case of de facto impossibility of performance86x For example, in Yang v. Shu (2018) 湘0681民初305号, the parties contracted to sell a quota to buy real estate property in a shantytown renovation project in 2013. However, the project was unexpectedly cancelled by the local government in 2017. Because the subject matter of the contract no longer existed and the performance became permanently impossible, the Basic People’s Court of Miluo City of Hunan Province terminated the contract based on the doctrine of change of circumstance. Similar cases include Jiang v. Liu (2011) 苏商再提字第0003号; Danzhoushi Nongye Jishu Tuiguang Zhongxin v. Ling Shilong (2015) 琼民抗字第18号; Dang v. Hu and Beijing Wo’aiwojia Fangdichan Jingji Co. Ltd. (2016) 京0102民初16060号; Guizhou Honghua Wuliu Co. Ltd. v. Zhou Xiaoya (2016) 黔0115民初3839号. and the legal impossibility of performance87x For example, in Wang and Mu v. Shandong Zhengda Xuqin Co. Ltd. Jiaonan Fen Gongsi (2018) 鲁15民终1403号, the parties entered a contract to cooperate in the pig-raising business on a farm in 2013 for a six-year term. In 2017, the local district-level government decided to restrict poultry farming to some regions of its district, and the farm in question was outside of the permitted areas. Therefore, the contract could no longer be performed legally. The Intermediate People’s Court of Liaocheng City of Shandong Province held that the new government decision was a change of circumstances which led to the impossibility of performance and frustrated the contract’s purpose. The court thus terminated the contract and ordered the defendant to share the plaintiff’s losses resulting from the termination according to the principle of fairness. Similar cases include Zhongguo Renmin Jiefangjun 93951 Budui v. Chen Fengming (2017) 青2801民初1822; Chongqingshi Jiangjinqu Baishazhen Baozhu Cunmin Weiyuanhui v. Zhong Yinmao (2018) 渝05民终2833号; Guizhou Zunyi Xiangjiang Lvse Chanye Fazhan Co. Ltd. v. Luo Jianwei (2016) 黔03民终1122号; Guangzhoushi Huacheng Zhiyao Chang v. Guangdong Yili Yiyao Co. Ltd. (2017) 粤01民终19878号; Sichuan Shiyou Tianranqi Jianshe Gongcheng Youxian Zeren Gongsi v. Sichuansheng Dujiangyan Renminqu Diyi Guanlichu (2018) 川0114民初4880号; Shaoxingshi Gong’an Xiaofang Zhidui Keqiaoqu Dadui v. Peng and Chen (2018) 浙06民终263号; Zhongguo Renmin Jiefangjun Di Wusanyi Yiyuan v. Xingaoyi Yiliao Shebei Gufen Co. Ltd. (2017) 吉0502民初2472号. by applying the doctrine of change of circumstances would be regarded as a wrong application of law after implementing the Civil Code.The Relationships between the Three Doctrines Regarding Unexpected Circumstance

4.3 Judicial Approaches to Restoring Contractual Equilibrium

Article 533 of the Civil Code has taken Article 6.2.3 of the UNIDROIT Principles for reference and introduced the pre-litigation process of renegotiation requested by the adversely affected party.88x Art. 26 of the Contract Law Judicial Interpretation II did not require renegotiation before seeking judicial relief. This shows that the law prefers the disrupted contractual equilibrium solved by party autonomy rather than by judicial intervention. If renegotiation fails within a reasonable time, either party may request the court89x If the parties have an arbitration agreement, they resort to the agreed arbitration institution for relief. to modify or terminate the contract in the light of the circumstances of the case and according to the principle of fairness. As Article 32(3) of the Judicial Interpretation of the Book on Contracts provides, the courts cannot terminate the contract if the parties request to modify it. In restoring the contractual equilibrium disputed by a change of circumstances, the court must consider how to fairly allocate the risk of the changed circumstances that the parties did not expect and address at the time of the conclusion. This is echoed by Article 32(3) of the Judicial Interpretation of the Book on Contracts, which requires judges to consider various factors ‘such as the time when the fundamental conditions of the contract undergo significant changes, the renegotiation between the parties, and the losses caused to the parties by the modification or termination of the contract’.

Despite exercising judicial discretion in deciding an appropriate judicial relief, Chinese courts have demonstrated the following practice of restoring contractual equilibrium, which may provide a comparative law reference for other jurisdictions.

First, Chinese courts have shown a preference for modification.90x Chinese legal scholars have supported this view; see W. Fang, ‘Elements of China’s Doctrine of Change of Circumstances and Reflection on Its Position’ (我国情势变更制度要件及定位模式之反思), 212(6) Law Review (法学评论) 57, at 62 (2018). The courts held that contract modification should be considered a priority unless it cannot redress the disrupted contractual equilibrium between the parties.91x See Fujiansheng Nanping Jiafu Gongmao Co. Ltd. v. Nanping Anran Ranqi Co. Ltd. (2016) 闽07民终322号; Shandong Binzhou Guanghe Mianye Co. Ltd. v. Binzhou Zhongfang Yintai Shiye Co. Ltd. (2016) 鲁1602民初2435号; Wuchengxian Shuili Gongcheng Co. Ltd. v. Xu Baozong (2018) 鲁1428民初975号; Wang and Huang (2018) 川0182民初649号; Xunda (China) Diandi Co. Ltd. v. Leinuosi Guoji Huoyun Daili (Shanghai) Co. Ltd. (2022) 沪民终525号. When a party invokes a request to terminate the contract, the court can maintain the contractual relationship by adapting the disrupted contract terms.92x See Qingdao Haiyunfeng Youting Fuwu Co. Ltd. v. Qingdao Dongfang Yingdu Youtinghui Guanli Co. Ltd. (2021) 鲁民终668号; the High Court of Shandong Province rejected the lessor’s request for termination of the lease agreement and decided that to postpone the rental payment was the best solution to overcome the lessee’s hardship caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and meanwhile maintain the transaction stability. For example, the plaintiff in Shandong Binzhou Guanghe Mianye Co. Ltd. v. Binzhou Zhongfang Yintai Shiye Co. Ltd.93x (2016) 鲁1602民初2435号. insisted on terminating the contract. However, the court ruled that when the foundation of the contract was amendable, modification of the contract should be preferred because it could promote the maintenance of transaction security and the stability of transaction order. It thus rejected the plaintiff’s request for termination and took the initiative to modify the contract. This was reiterated in the SPC’s guidance on how to apply the doctrine of change of circumstances to COVID-19-related cases.94x See n. 38 above.

Second, Chinese courts disapprove of an adaption that changes the nature of the obligation when considering how to restore the contractual equilibrium through modification. For example, in Guangzhoushi Huacheng Zhiyao Chang v. Guangdong Yili Yiyao Co. Ltd.,95x (2017) 粤01民终19878号. the parties contracted in 2006 to cooperatively manufacture and manage medicines. They signed another contract in 2011 to further their cooperation in manufacturing traditional Chinese medicine of Pithecellobium Clypearia; they agreed that the defendant would manufacture and provide the Pithecellobium Clypearia extract to the plaintiff. However, in 2014, the State Food and Drug Administration issued a new law that required Pithecellobium Clypearia extract to be manufactured only by a licensed company. However, the defendant did not have the necessary licence. The Intermediate People’s Court of Guangzhou City of Guangdong Province held that the new law amounted to a change of circumstances and had changed the parties’ shared assumption that the defendant was qualified to produce the Pithecellobium Clypearia extract. The defendant proposed to preserve the contractual relationship with the plaintiff by introducing a third party qualified to manufacture Pithecellobium Clypearia extract, but the plaintiff disagreed. The court considered that proposal and finally did not endorse it because the court accepted the plaintiff’s argument that introducing a third party to perform the obligation would substantially change the nature of the defendant’s obligation and influence the parties’ original intentions in making the contract.