Delivering Justice Solutions to Persons with Disabilities through Online Dispute Resolution Platforms

-

1 Introduction

Access to justice for persons with disabilities is a challenge, globally. Persons with disabilities face physical, social and legal barriers to access justice systems. In India, although not extensively studied and documented to draw conclusions, persons with disabilities are almost invisible from the justice system – meaning that there are too fewer people with disability participating as lawyers, litigating parties, judges, paralegals or complainants.

Knowing that existing justice systems are riddled with challenges, alternate dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms are gaining traction, globally. Agami1x https://agami.in/. organized an International Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) Forum 20232x https://odr2023.org/. on 17-18 March 2023 at the Bangalore International Centre, in Bengaluru, India, to mobilize conversations on ODR. Pacta3x https://www.pacta.in/. and EnAble India4x https://www.enableindia.org/. collaborated to anchor a session on Inclusive ODR for Persons with Disabilities: A Playground5x https://odr2023.org/#agenda. organized as part of the larger ODR forum. The session helped glean insights from experts and the audience on the effective formation and delivery of ODR as a justice-delivery system for persons with disabilities.

The workshop culminated into elements of a preliminary blueprint for ODR for persons with disabilities in India. -

2 Situating Justice for Persons with Disabilities

2.1 A Global Context

Globally, persons with disabilities remain marginalized and fundamental rights guaranteed under the constitutions of many countries are not provided to them. Access to justice is a crucial (but paradoxical) right (i.e., those who are most vulnerable and susceptible are denied their rights) and fundamental freedom that most persons with disabilities do not have. With 16% of the world’s population being disabled6x World Health Organization. (2023, March 7). Disability. WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health. (or 1.3 billion individuals with disabilities), the inaccessibility and denial to their fundamental rights perpetuates the cycle of marginalization and vulnerability.

Article 12 and 13 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities7x United Nations. (n.d.). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD). United Nations. http://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd. (UNCRPD) (2007) assures equal recognition before the law and access to justice, respectively. Based on the UNCRPD commitments that have been ratified by 186 countries and signed by 164,8x United Nations. (n.d.). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD). United Nations. https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd#:~:text=There%20were%2082%20signatories%20to,1%20ratification%20of%20the%20Convention. basic rights are to be served to all persons with disabilities. Furthermore, based on the UNCRPD, the UN Human Rights Special Procedures drafted ten international principles and guidelines for access to justice for persons with disabilities,9x United Nations. (2020, August). International principles and guidelines on access to justice for persons with disabilities. United Nations.

https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2020/10/Access-to-Justice-EN.pdf. including non-denial of justice based on disability. However, the reality of the practice of justice, globally, is far from the intentions of the international conventions10x Beqiraj, J., McNamara, L., and Wicks. V. (2017, October). Access to justice for persons with disabilities: From international principles to practice. International Bar Association. https://www.biicl.org/documents/1771_access_to_justice_persons_with_disabilities_report_october_2017.pdf. and guidelines.

Furthermore, in its true spirit, the Sustainable Development Goals (2020) in SDG 1611x United Nations. (n.d.). Goal 16: Promote just, peaceful and inclusive societies. United Nations. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/peace-justice/. emphasize the promotion of peaceful societies, provision of access to justice to all and building strong institutions that are inclusive, effective and accountable. Specifically, Goal 16.3: “Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all”. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development12x Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. (n.d.). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda. bears potential to find practical solutions to improve welfare, protect their rights and increase access to services for persons with disabilities. However, with paucity of available data13x Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. (n.d.). SDG Indicators Metadata repository. Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/?Text=&Goal=16&Target=. on the number of persons with disabilities (particularly when not disaggregated) accessing justice globally, the extent of progress on SDG 16.3 targets are hard to assess.2.2 Barriers to Justice

Extant work has been done globally to document reasons on why persons with disabilities are unable to access justice.

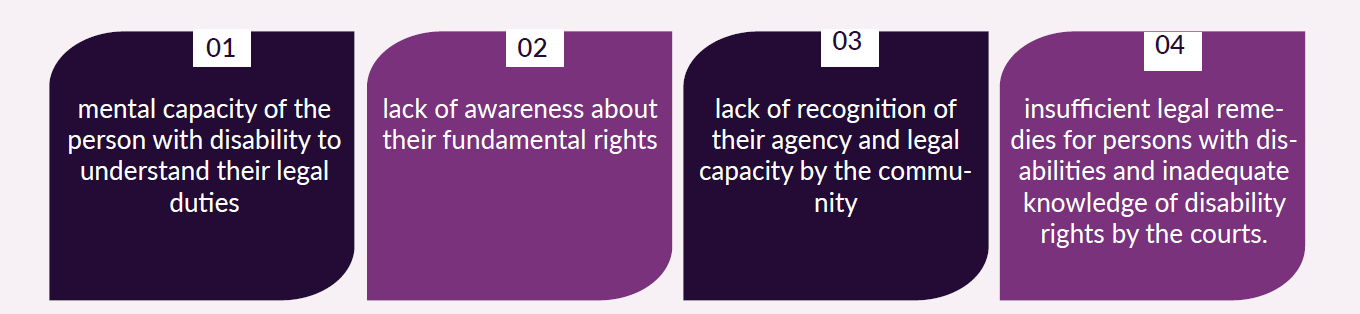

Eilionóir Flynn et al. (2019) described several barriers that persons with disabilities face in the legal system. Figure 1. highlights some of these barriers.14x Flynn, E., Moloney, C., Fiala-Butora, J., and Echevarria, I.V. (2019). Access to justice of persons with disabilities. Institute for Lifecourse and Society. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Disability/SR_Disability/GoodPractices/CDLP-Finalreport-Access2JusticePWD.docx.Barriers to Justice for Persons with Disabilities

Larson (2014) reiterated that the inexperience15x Larson, D. A. (2014). Access to justice for persons with disabilities: An emerging strategy. Laws, 3(2), 220-238. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-471X/3/2/220. of legal professionals to work with persons with disabilities was one of the primary reasons for impediments in persons with disabilities accessing the legal system.

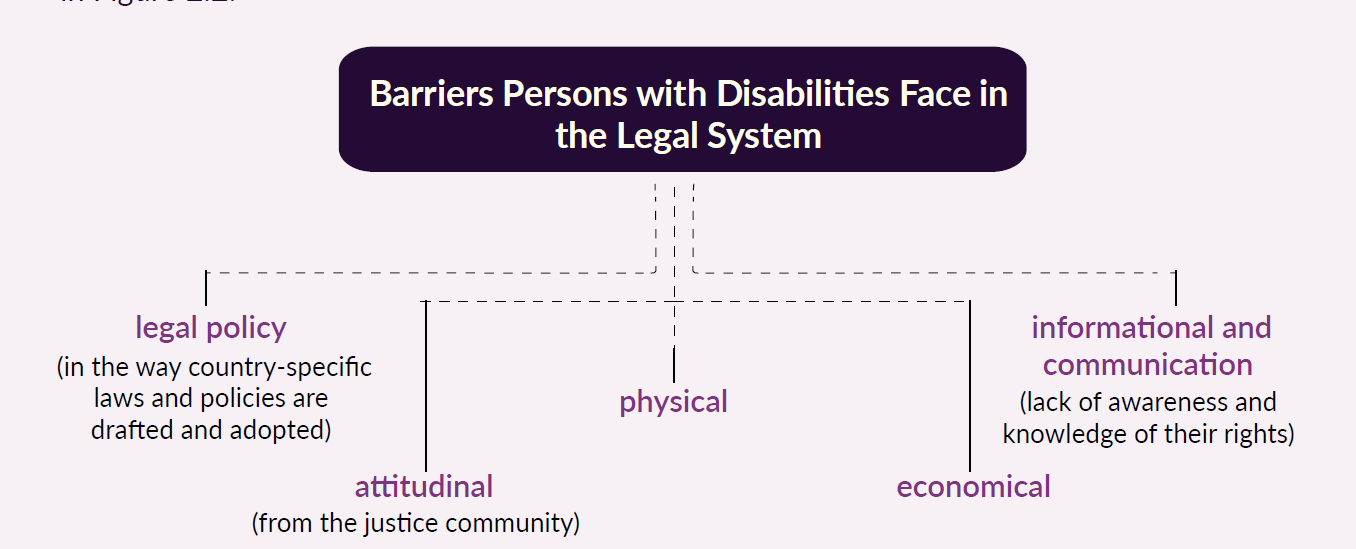

In a UN toolkit developed for Africa,16x Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (n.d.) Toolkit on disability for Africa. Access to justice for persons with disabilities. United Nations. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/disability/Toolkit/Access-to-justice.pdf. the manual discusses several barriers to access to justice for persons with disabilities. Some of the common barriers that persons with disabilities face, as described in the article, are categorized into different themes as depicted in Figure 2.Thematic Breakdown of Barriers in Access to Justice for Persons with Disabilities

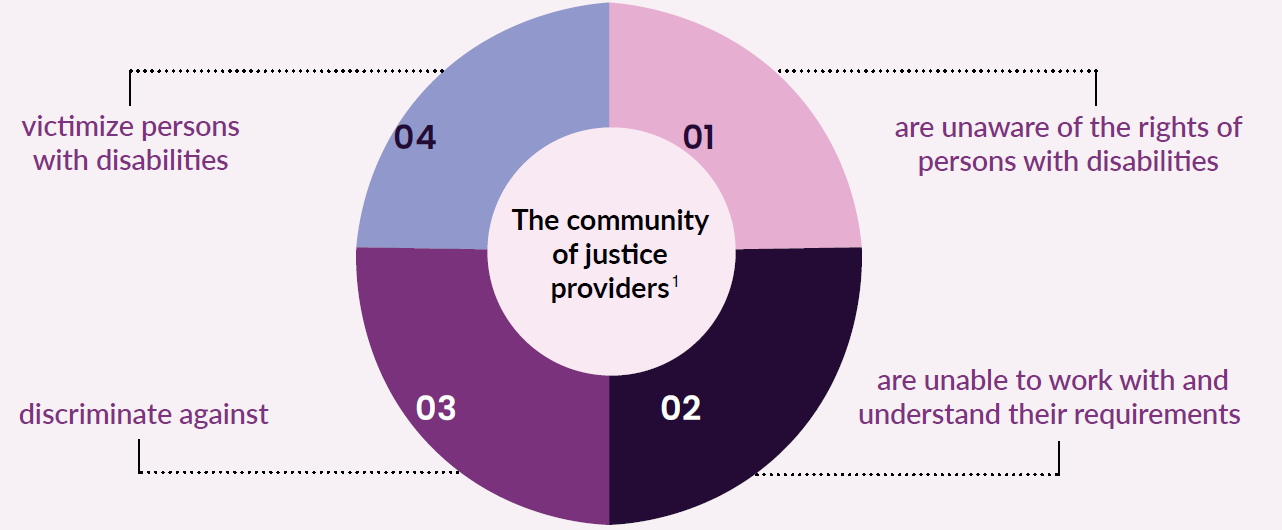

Apart from some of the barriers stated in Figure 2, the report highlighted the role of the court systems and service providers such as victim advocates or healthcare providers, legal personnel and police in delivering justice to persons with disabilities, which is highlighted in Figure 3.

Barriers Propagated by Community of Justice Providers Including Victim Advocates, Healthcare Providers, Legal Personnel and Police

These barriers, though specific to African nations, are present in other countries as well particularly in low- and middle-income countries like India [although we lack adequate research to substantiate this claim]. Thus, access to justice becomes a greater hurdle for persons with disabilities, when the justice providers themselves are underprepared to serve their cause.

2.3 The Indian Context

The Rights of Persons with Disabilities17x The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act. (2016). Government of India. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15939/1/the_rights_of_persons_with_disabilities_act%2C_2016.pdf. (RPWD) Act (2016) guarantees access to justice (Section 12(1)) for persons with disabilities as their basic right. About 2.21% (Census, 2011)18x Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. (2011). C-21: Disabled population by type of disability, marital status, age and sex (India & States/UTs). Government of India.

https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/43468. of India’s population is disabled (acknowledging that the numbers of persons with disabilities may have gone up over the last decade or so; and a lack of updated credible, accessible numbers on persons with disabilities in India). People with disabilities experience stigma, discrimination, violence and non-inclusion which is compounded when their disabled identity intersects19x Liasidou, A. (2013). Intersectional understandings of disability and implications for a social justice reform agenda in education policy and practice. Disability & Society, 28(3), 299-312. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09687599.2012.710012. with other marginalized identities such as gender, caste, class, race and religion. Due to such vulnerabilities, access to justice (from a human rights perspective)20x Mohit, A., Pillai, M., and Rungta, P. (2006). Rights of the disabled. National Human Rights Commission. https://nhrc.nic.in/sites/default/files/DisabledRights_1.pdf. for the population becomes a critical component of their upliftment and well-being, which, unfortunately, remains hard to come by.21x Ministry of Human Resource and Development. (n.d.). Access to justice. Access to justice and persons with disabilities. Government of India. http://epgp.inflibnet.ac.in/epgpdata/uploads/epgp_content/Law/02._Access_to_justice/10._Access_to_Justice_&_Person_with_Disability/et/5637_et_10ET.pdf.For persons with disabilities, the four pillars namely, awareness, accessibility, adaptability and availability (4 A Framework) (adopted for education22x Right to Education. (n.d.). Primer No. 3: Human rights obligations: Making education available, accessible, acceptable and adaptable.

https://www.right-to-education.org/resource/primer-no-3-human-rights-obligations-making-education-available-accessible-acceptable-and. of children with disabilities – with education being a basic human right) are crucial within the formal and informal justice systems for them to enjoy equal rights as other citizens.

Robust data and adequate research on the barriers are required to understand the on-ground challenges, plan impactful policies and develop meaningful solutions that will help increase the access to justice for persons with disabilities. However, even today, we lack the literature on the barriers faced by persons with disabilities in accessing justice in India, though there is sufficient anecdotal and lived experience justifying this. Data on participation of persons with disabilities in the judicial systems in India is inadequate. This further hinders evidence-based approaches to make the legal system work for persons with disabilities. -

3 ODR for Persons with Disabilities: Setting the Stage in India

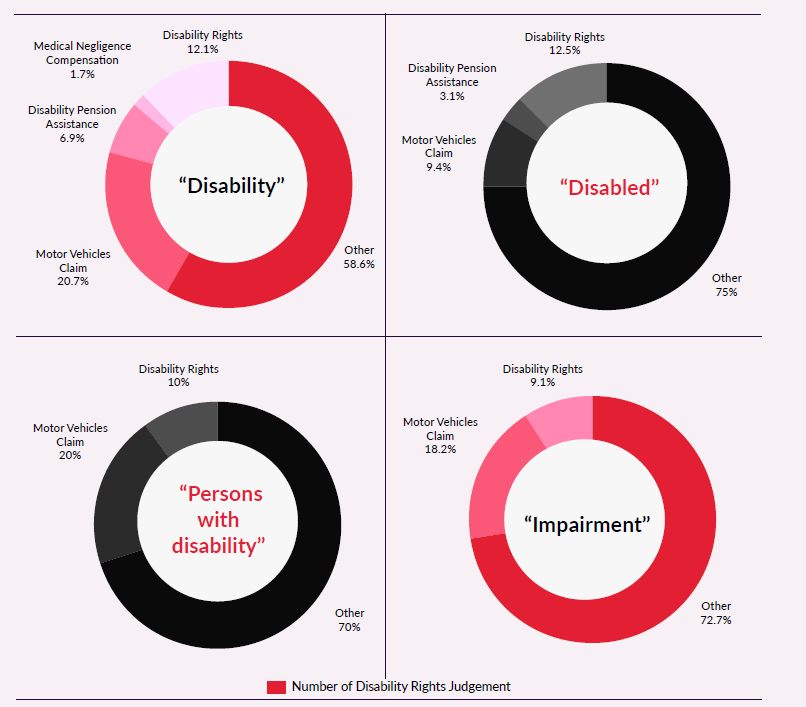

When we consider the mechanisms of justice that exist today for persons with disabilities in India, the formal court systems are among the most relied upon. The Supreme Court in 2022 delivered judgements and orders to protect the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. An overview of the type of issues categorized based on search keywords was published by a legal news portal (LiveLaw) reproduced in Figure 4.23x Das, A. (2022). How the supreme court protected disability rights in 2022? LiveLaw. https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/how-supreme-court-protected-disability-rights-2022-217751?infinitescroll=1.

Supreme Court Judgements on Issues Faced by Persons with Disabilities Source: Das, A. 2022, How the Supreme Court Protected Disability Rights in 2022. LiveLaw.

Source: Das, A. 2022, How the Supreme Court Protected Disability Rights in 2022. LiveLaw. 3.1 Legal Delivery Mechanisms by the Government

Unfortunately, even today, not all court systems, particularly the lower courts are known to be inclusive and disability-friendly24x Tripathy, S. (2021, October 25). India must build, re-build its courts for disabled. Judicial infra key to justice delivery. The Print. https://theprint.in/opinion/india-must-build-re-build-its-courts-for-disabled-judicial-infra-key-to-justice-delivery/756058/. from the perspective of justice seekers. Despite barriers faced in the formal court systems, one cannot ignore the efforts taken by the government to provide affordable, quality and timely justice to all.

In 1987, the Government of India enacted the Legal Services Authorities Act25x The Legal Services Authorities Act. (1987). https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/19023/1/legal_service_authorities_act%2C_1987.pdf. to organize Lok Adalats for delivery of justice based on the principles of equal opportunity. Based on the Legal Services Act, about 29,05026x Ministry of Law and Justice. (2022, April 7). Legal aid to the disabled. Government of India. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1814545. persons with disabilities were provided legal services between 2018 and January 2022

Other legal services institutions have also been set up across the country at various levels including the Supreme Court

The National Legal Services Authorities27x https://nalsa.gov.in/. (NALSA) has also created easy access to legal aid through mobile apps.

3.2 Other Legal Measures to Deliver Justice for Persons with Disabilities

The Office of the Chief Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities28x http://www.ccdisabilities.nic.in/. was set up under the Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995 to provide and safeguard the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in India. Now, under the RPWD Act, 2016, Section 74, a Chief Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities (CCPD) has been appointed. In 2022, until November, 365 cases were disposed of by the CCPD.29x http://www.ccdisabilities.nic.in/resources/leading-orders-of-ccpd. The CCPD is being given increasing responsibilities by the higher courts to take up matters related to the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and provide judgements in a timely manner. In a recent judgement30x Disability Right through Courts. (2014, May 14). Delhi HC redefines the scope of powers of chief commissioner disabilities. https://www.disabilityrightsindia.com/2014/05/delhi-hc-redefines-scope-of-powers-of.html. concerning the reservation in employment of persons with disabilities in teaching positions, the Delhi High Court provided the CCPD with powers to enforce its directions. The high court went on to direct the CCPD to dispose of the case within three days and ensure that the orders of the CCPD were complied with.

All the above-described modes are positive steps taken to ensure that persons with disabilities have access to timely, effective, abiding and hassle-free justice. Despite the government taking measures to ensure accessible, timely and fair judgement is provided to persons with disabilities, justice does not always reach all alike due to inaccessibility and lack of awareness.3.3 ODR: An Alternate Recourse

Larson (2014) suggested ODR as a viable mode to increase access to justice for persons with disabilities. The author suggested that ODR forms a quick and inexpensive solution for the group not having to go through traditional justice-serving mechanisms (i.e., “of relying on litigation”). ODR, a technological-based ADR, will reduce the brick-and-mortar physical accessibility concerns for persons with disabilities. Furthermore, ODR can be delivered both synchronously and asynchronously, which provides persons with intellectual or motor impairments an opportunity to participate effectively.

3.3.1 Advantages and Challenges of ODR for Persons with Disabilities

The developments in the ODR ecosystem have opened up possibilities of better access to justice for persons with disabilities. The noteworthy advantages of ODR include:

Convenience: Access to the platform to file a claim, negotiate/mediate and follow-up a procedure anytime and from anywhere.

Saves Time: Reduces long waiting periods associated with conventional/court-based resolution.

Simple and Versatile: ODR can be adopted and adapted for almost all types of disputes and follows simple procedures dispensing the need for lawyers/paralegals.

Saves Costs: Limited cost of services as providers usually charge low fees knowing the low value but high volume of disputes.

Equal and Equitable: Enables equitable access since all parties have the opportunities to simultaneously access the same information in a standard environment.

Unlocks Data: ODR unlocks data and access to data allowing for efficient processing over time.

Reduced Dependencies: Certain forms of ODR dispenses with the need for access to lawyers or paralegal resources to pursue dispute resolution.

These advantages, however, are not absolute as there exist several challenges which persons with disabilities might face with regard to ODR. The effectiveness of ODR as a mode of dispute resolution is contingent upon overcoming these challenges which include:

Digital Inaccessibility: Unless the platform for ODR takes into consideration access in its design for all kinds of disabilities, it will not be a useful service. Accommodating accessibility requirements can be complex.

Technological Inaccessibility: Limited technological capacity and limited internet penetration can limit the utility of internet-based ODR services for a certain section of persons with disabilities.

Cultural Insensitivities: Discomfort with internet-based communications and services as opposed to face-to-face communication makes ODR challenging.

Non-accountable Systemic Mechanisms: At a more systemic level, there are currently no mechanisms of accountability to ensure transparent and fair processes on ODR platforms.

3.3.2 ODR in the Context of India’s Judicial and Legislative Systems

Legislative Frameworks: Though India has yet to formally adopt ODR in the judicial and legislative domains, developments point towards its recognition as a valid mechanism for dispute resolution. Several recent legislations and amendments have been made to promote ADR mechanisms at both pre- and post-litigation stages, which signal preparedness for ODR (See Annexure 1 for ADR-related laws in India).

While Lok Adalats (one of the ADR mechanisms) were set up in 1987 to undertake conciliation, more recently, there have been several mandates for the setting up of committees, panels and cells for grievance redressal through mediation. For instance, the Industrial Relations Code, 202031x Ministry of Law and Justice. (2020, September 29). The industrial relations code. Government of India. https://labour.gov.in/sites/default/files/ir_gazette_of_india.pdf. – provides for the appointment of conciliation officers and conceives conciliation as the first level of dispute resolution. Similarly, under the Consumer Protection Act (E-Commerce) Rules, 2020,32x Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. (2020). https://consumeraffairs.nic.in/sites/default/files/E%20commerce%20rules.pdf. e-commerce entities are required to provide for an internal grievance redressal mechanism. These steps can be thought of as the foundation for setting up of ODR. When seen together with technology-related laws (Annexure 2) that recognize electronic evidence and records under certain conditions, India’s preparedness for ODR becomes more apparent.

Judicial Preparedness: The Indian judiciary has adopted new Information and Communication Technology (ICT) to facilitate ODR. For instance, the e-court’s mission33x Nalanda Judgeship. e-Court Mission Mode Project. https://districts.ecourts.gov.in/nalanda/e-court-mission-mode-project. intends to increase ICT integration with justice-delivery systems. The mission has integrated judgements of all Indian courts creating a National Judicial Data Grid34x National Judicial Data Grid. (2020, December 31). https://njdg.ecourts.gov.in/njdgnew/index.php. (NJDG) and unified Case Information System35x E-Courts Mission Mode Project. (2022, January 21). Case Information System Information Brochure. https://districts.ecourts.gov.in/case-information-system-information-brochure. (CIS). There is an e-filing and e-signing facility for district courts and high courts. There has also been the adoption of AI-powered software for the purpose of translation of judgements under the Supreme Court Vidhik Anuvaad Software36x Supreme Court of India. (n.d.). Press release. https://main.sci.gov.in/pdf/Press/press%20release%20for%20law%20day%20celebratoin.pdf. (SUVAS). Other such initiatives include the e-Lok Adalats that are now being held in different states.37x Ministry of Law and Justice. (2022, August 5). Promotion of e-Lok Adalat. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1848734. In 2020, the Delhi High Court established 34 exclusive paperless courts38x High Court of Delhi. (2020). Digital NI Act Courts in Delhi. Project implementation guidelines. https://delhidistrictcourts.nic.in/DigitalNIActCourtsProjectImplementationGuidelines.pdf. for hearing matters registered under the Negotiable Instruments Act. It allowed litigants to appear in courts virtually and enabled all procedures to be completed digitally.

Judicial Precedents: The judiciary has not stopped at adopting ICT, but has also ruled in favour of using ICT in justice-delivery systems (case-specific details can be found in Annexure 3). The Supreme Court has held that video-conferencing is a valid mode for collecting evidence39x Supreme Court of India. (2003). The State of Maharashtra vs. Praful Desai. https://main.sci.gov.in/jonew/judis/19114.pdf. and taking testimony from witnesses. Furthermore, it has also made the observation that for certain categories of cases, physical presence should not be mandatory and such cases can be partly or entirely concluded online.40x All India Legal Forum. (2021). Legal fortnight. February Edition 1. https://www.nluo.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Legal-Fortnight-Febedn-vol1.pdf. Furthermore, the court has considered online arbitration, and the arbitration agreement as valid under the condition that compliance41x Kinhal, D. et al. (2020). ODR: The future of dispute resolution in India. Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy & JALDI. https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/research/the-future-of-dispute-resolution-in-india/. is met “with Section 4 and 5 of the Information Technology Act (IT Act), 2008 read with Section 65B of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 and provisions of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996”. The simultaneous movement to integrate technology in dispute resolution and reliance on ADR mechanisms is a clear indicator that India is gearing itself to logically transition towards ODR.

Other Measures: A NITI Aayog ODR Policy Plan for India42x The NITI Aayog Expert Committee. (2021, October). Designing the future of dispute resolution. The ODR policy plan for India. NITI Aayog. https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2021-11/odr-report-29-11-2021.pdf. report (November 2021) recommended legitimizing ODR as a valid mechanism to deliver justice. In December 2021, the draft Mediation Bill43x The Mediation Bill. (2021). https://legalaffairs.gov.in/sites/default/files/mediation-bill-2021.pdf. was released under which online mediation was an available option to parties at any stage of mediation proceedings, including pre-litigation mediation. The article acknowledged the need for a robust and comprehensive data protection law to address confidentiality and security concerns that ODR gives rise to. To this end, the Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 202244x The Digital Personal Data Protection Bill. (2022). https://www.meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/The%20Digital%20Personal%20Data%20Potection%20Bill%2C%202022_0.pdf. was released, which was passed by the House in August 2023. However, the 2023 Act still carries many loopholes45x Sharma, N., Gupta, P., and Iqubbal, A. (2022). CUTS comments on the draft digital personal data protection bill. CUTS International. https://cuts-ccier.org/pdf/cuts_comments_on_the_digital_personal_data_protection_bill-2022.pdf. that have implications for ODR platforms and their obligations as data fiduciaries. -

4 ODR for Persons with Disabilities: Towards a Blueprint

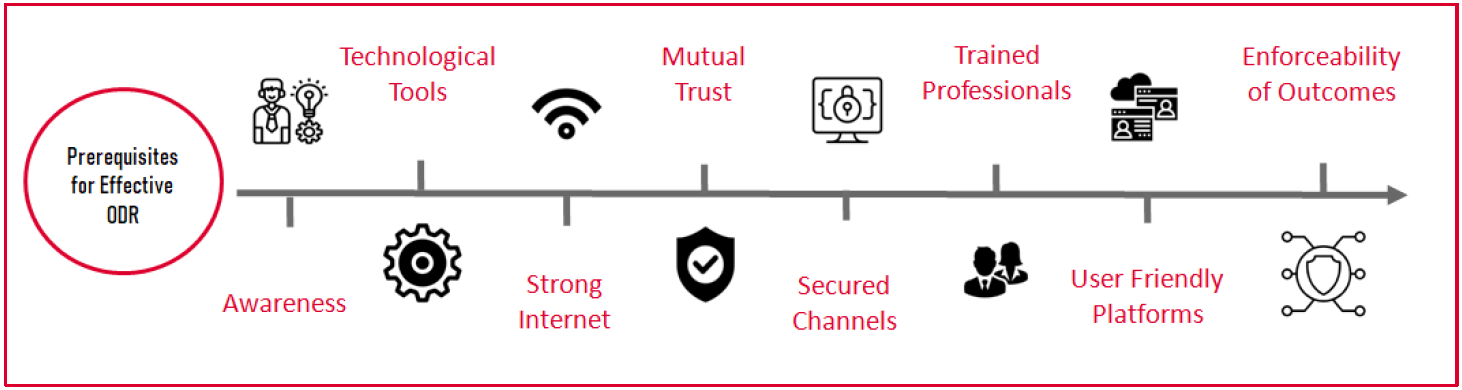

In a recent report46x Thomas, Z. (2022, January 28). What constitutes ‘dispute’ under arbitration & conciliation act? Madhya Pradesh High Court Explains. LiveLaw. https://www.livelaw.in/news-updates/madhya-pradesh-high-court-dispute-arbitration-conciliation-act-190521. entitled ‘ODR: The future of dispute resolution in India’ by Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy and Justice, Access and Lowering Delays in India (JALDI), several aspects of ODR adoption in India have been covered. By situating ODR as a mode of dispute resolution in the current societal, legal and judicial contexts, the report provides for a blueprint or a template that maps out the prerequisites for an effective ODR system in India.

Components of an Effective ODR System: a Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy and JALDI Blueprint Source: Kinhal, D. et al. (2020). ODR: The Future of Dispute Resolution in India. Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy & JALDI.

Source: Kinhal, D. et al. (2020). ODR: The Future of Dispute Resolution in India. Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy & JALDI. The components covered in the model (shown in Figure 5) include both supply side as well as demand side aspects. On the demand side, the model points towards the need for greater awareness, better trust and access to technology (i.e., the internet, telephones and other devices to support ODR). On the supply side, components such as secure channels, trained professionals and user-friendly platforms are taken into consideration. The final component is the enforceability of the ODR outcomes, which is critical to making it a dependable and meaningful mode of resolution.

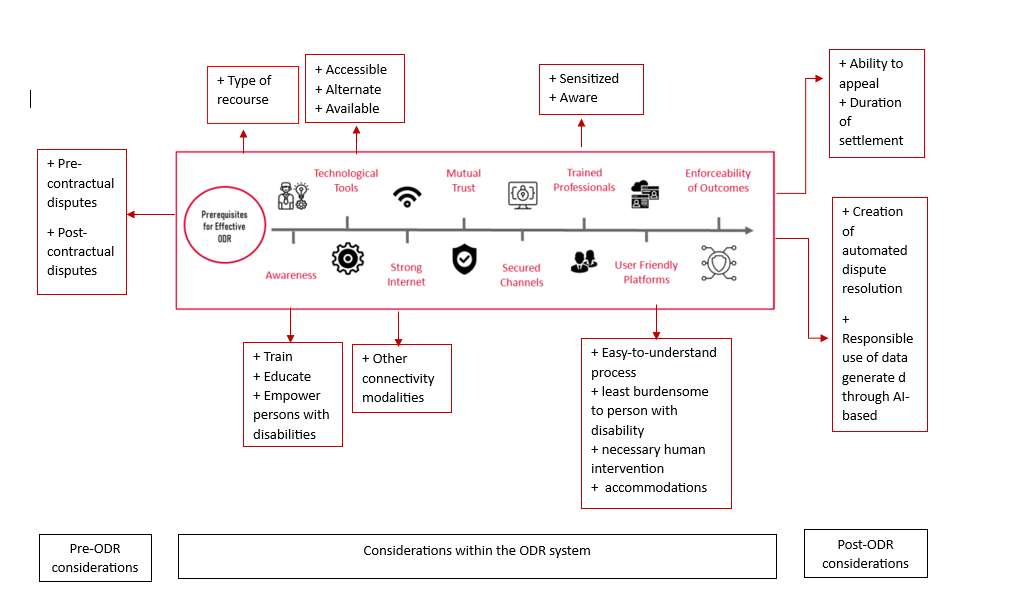

When it comes to ODR for persons with disabilities, it becomes important to apply a disability lens and ensure that the resulting model for dispute resolution is inclusive and fair. A disability-friendly framework for ODR (as provided in Figure 6) would mean additional considerations for enabling inclusion of different types of disabilities and the preparedness from the person with disability’s ecosystem.A Blueprint of an Inclusive ODR System for Persons with Disabilities

4.1 Pre-ODR Considerations: What Types of Disputes as They Pertain to People with Disabilities Can Be Settled through ODR?

During the consultations, two key considerations arose in respect of types of disputes for the applicability of ODR. These were:

4.1.1 ODR System Must Have Jurisdiction over Pre-Contractual Issues

The term ‘Dispute’ is not defined under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. The Madhya Pradesh High Court in Indian Oil Corporation Ltd. and others v. M/s Tatpar Petroleum Centre (A.A. No.80/2021) defined the term dispute to mean – “An assertion by one and denial/said assertion by another”.

When it comes to people with disabilities, an important class of disputes that needs to be addressed is pre-contract disputes. Pre-contract disputes refer to disputes that arise prior to signing the contract. Several people with disabilities are deprived of services by virtue of a disability-first approach. Some instances of a ‘disability-first’ approach were described:Despite having a good CIBIL score and being a taxpayer, I was denied a home loan…banks discriminate as they are apprehensive of giving loans to persons with disabilities … They consider the loan to the disabled a risk factor.

Persons with disabilities cannot open demat accounts or have health insurance policies under their names, since these financial service providers take a disability-first approach…

These lived experiences go to show that it is important for an ODR system to envisage settlement of pre-contractual issues for the ODR to be meaningful to persons with disabilities. This will enable persons with disabilities to enforce their rights without having to resort to writ petitions or invoking the jurisdiction of the CCPD/State Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities (SCPD).

4.1.2 ODR System Must Have Jurisdiction over Post-Contractual Issues

This refers to disputes arising out of a valid contract entered between an individual and an institution. For instance, when a person with disability enters into contracts with service providers like Ola/Uber or medical services, disputes arising out of such contracts too can voluntarily get referred to ODR. It is germane to note that the National Consumer Helpline (1915) as a part of the Department of Consumer Affairs, Integrated Grievance Management System47x Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food & Public Distribution. (n.d.). Integrated grievance redressal mechanism. Government of India. https://consumerhelpline.gov.in/about-portal.php. (INGRAM) has been set up as a pre-litigation online grievance redressal mechanism. Many private companies, most e-commerce platforms48x Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food & Public Distribution. (n.d.). Integrated grievance redressal mechanism: Convergence partners. Government of India. https://consumerhelpline.gov.in/convergence-partners.php. and several public authorities49x Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances. (n.d.). List of nodal public grievance officers. Government of India. https://pgportal.gov.in/Home/NodalPgOfficers. too have listed themselves up for grievance redressal under the INGRAM platform. However, the INGRAM is inaccessible to people with disabilities. Similarly, under the government’s Accessible India Campaign, the ‘Sugamya’ mobile application50x Google Play. Sugamya Bharat App. (2023, September 21). https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.geostat.sugamyabharatMOH&hl=en_IN&gl=US&pli=1. has been launched with a vision to create an inclusive barrier-free environment by identifying the gaps and facilitating their remediation by concerned authorities. The application is intended to crowdsource the issues and possible solutions related to accessibility from citizens. However, the success of the App remains limited.

4.2 Features of an Effective ODR for Persons with Disabilities

The features of the ODR platform for persons with disabilities (as shown in Figure 6) reflect technological, procedural and systemic components that will enable effective justice-delivery mechanisms (also refer to Larson, 2020).51x Larson, D. A. (2020). ODR accessibility for persons with disabilities: We must do better. Online Dispute Resolution: Theory and Practice (2nd ed. Eleven International Publishers, Fall 2020 Forthcoming). https://deliverypdf.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=876127020083070018119021126084017098032032005076035071068096124022104024109097072123038034063030056048039112094092106013087118019016043042041101013012029071100100003073039013113003098001067013117012082115090117117075080025096018125125081102099101000&EXT=pdf&INDEX=TRUE.

Below, we describe the features for an inclusive ODR system based on Figure 6.Type of Recourse within the ODR System: In the ODR system, disputing parties must (to the extent possible) be able to exert a choice on the type of recourse (namely, arbitration, conciliation, mediation or negotiation), which is to be chosen based on the reason of dispute or grievance. For persons with disabilities, this is an important stage for successful/effective participation in the ODR process. Pathways of least burden (physical, financial and emotional) must be chosen to resolve/address disputes at the earliest.

Awareness: Fundamental rights cannot be taken for granted with respect to marginalized groups. Persons with disabilities often share a complex relationship with their entitlements and rights due to the socio-legal interpretation of their decision-making and legal capacity, and a multitude of constraints in implementing laws and policies that guarantee rights and entitlements. Awareness through universal permeation of information, access to information on demand will be foundational to access to justice for people with disabilities. Additionally, any recourse (chosen above) requires educating and making aware the person with disabilities regarding the procedures, advantages and limitations of the recourse. This forms an important stage in the ODR system to ensure that the person with disability is fully prepared to go through the process.

Technological Tools: Recent amendments to the RPWD, 2016 rules52x Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. (2023, May 10). Notification. Gazette of India. Government of India. https://disabilityaffairs.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/RPwD%20(Amendment)%20Rules%2C%202023%20-%20Accessibility%20standards%20on%20ICT%20products%20and%20Services_compressed.pdf. mandate compliance with the IS 17802 (Part 1 and 2), 2022 to ensure accessibility of “Websites, apps, information and communication technology based public facilities and services, electronic goods and equipment which are meant for everyday use, information and communication technology based consumer products and accessories for general use with persons with disabilities, and other products and services which are based on information and communication technology”. In line with this mandate, ODR technological accessibility must be ensured for persons with disabilities. In case of unavailability of such accessible technology, alternate, accessible and available technological modes of delivery must be chosen to ensure that the intersectional digital divide does not hamper access to justice.53x Chandola, B. (2022, May 20). Exploring India’s digital divide. Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/exploring-indias-digital-divide/.

Strong Internet: Strong internet connectivity is a prerequisite for effective delivery of ODR. However, in developing countries like India, the digital divide remains. For persons with disabilities who are marginalized and access to technology is not always granted,54x Abhijith, S.R. (2020, December 28). Digital Disability Divide: A problem to address for an inclusive development [Post]. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/digital-disability-divide-problem-address-inclusive-development-s-r/?trk=public_profile_article_view. the ODR system must ensure that alternate modes of communication such as telephones/IVRS integration are utilized and those forms of technology enable adequate connectivity.

Mutual Trust: People with disabilities would need to embrace ODR platforms as a trust-worthy and viable option for dispute resolution. Building trust would entail that platforms have necessary assistive technology, assure confidentiality and do not penalize people for process mistakes. Additionally, trust building will also be contingent on the process itself being impartial, sensitive to the specific challenges of people with disabilities in justice-seeking, and is an effective channel of justice delivery. Transparency in the system and its process is also crucial to assure persons with disabilities that the ODR system is impartial, unbiased, non-discriminatory and equitable.

Secured Channels: ODR systems must adopt guidelines and standards of data privacy that are not merely compliant with the law but assure its users of good standards of data security and data privacy practices. Even as data emanating from these ODR systems further hone the technology that enables ODR systems, ethical use of data is paramount.

Trained Professionals: Professionals in the ODR delivery ecosystem need to be sensitive and aware to the needs of persons with disabilities. To address the lack of capacity within the justice system to effectively address the needs of persons with disabilities, awareness, capacity building and training should be initiated at the level of the curriculum/educational programmes, such as part of legal courses, judicial training and/or other relevant programmes. Further, efforts must be taken to sensitize practising justice providers within the ODR system on the ways to effectively deliver justice to persons with disabilities by holding a person-centric approach.

User-Friendly Platforms: ODR platforms must be user-friendly providing intuitive features to ensure that the user is able to interact with and navigate through the features without any barriers. Persons with disabilities, however, need more conscious measures to be inbuilt to be able to participate effectively in the ODR space. Features such as easy-to-understand processes, procedures that are least burdensome to the person with disability and maintaining affordability would be key features of a user-friendly platform. Additionally, the platform must provide necessary human interventions and accommodations for persons with disabilities so as to allow effective, non-threatened participation. Furthermore, access to low-cost justice solutions must be made available for persons with disabilities caught in the cycle of marginalization/non-inclusion/and poverty. If not offered sustainable/accessible justice solutions, the paradox (those who are most vulnerable and susceptible are denied their rights) will continue to remain.

4.3 Post-ODR Considerations

Enforceability of Outcomes: Once the decision about the issue in hand has been taken within the ODR system, considerations need to be made on appeal mechanisms and the period of limitations in appeal. The question of whether the decision is binding on the parties and enforceable in a court of law will also need to be clearly laid out.

Considerations for Artificial Intelligence-Driven (Automated) Dispute Resolution: An ODR results in the generation of large quantities of data pertaining to people with disabilities. With the advancement of artificial intelligence technologies, it is likely that data unleashed through ODR systems would be used to create models for automated dispute resolution. The data must be used ethically and responsibly and with the highest regard to protect data privacy rights of the individuals. Further, once such AI models are developed, they must be cautiously deployed and the impact must be closely watched and audited to identify and mitigate inequitable outcomes.

4.4 Enablers of the ODR Mechanism

The enablers in the ODR ecosystem form an important aspect of the systemic component who will drive efficient and effective justice-seeking and justice-delivery mechanisms within the ODR system. The key stakeholders who are also considered within the wrap-around system are depicted in Figure 7.

Enablers of an Effective Inclusive ODR Ecosystem

In order for the ODR system to function effectively, the role of several actors and stakeholders that provide wrap-around support to the ODR system must be acknowledged. The members of the wrap-around support groups are not to be viewed just as an aspirational support-system, but as catalytic participants, with the ability and intrinsic motivation to carry the successful ODR on their shoulders. Neither should the list below be viewed as being consummate or static. Pathways for their contribution to the ODR support must be identified to maximize their impact and participation in the success of ODR for people with disabilities. These pathways are also bound to evolve with the changing circumstances.

Five groups of Catalytic Wrap-Around Service Providers and their roles are identified below:

Group 1: Legislators, Public Authorities and Multilateral Organizations: This group of stakeholders is responsible for drafting laws, policies and frameworks for law and policies that advance the cause of access to justice for people with disabilities. Since the development of ODR is in the nascent stages in India, it is crucial for this group to encourage the adoption of “inclusion by design” principles to ensure that the ODR system is designed to work for people with disabilities without creating the same challenges as the traditional justice systems.

Group 2: Civil Society Organizations, Philanthropists, Advocacy Organizations and Capacity Builders: This group of stakeholders actively engages with the group of PwDs implementing programmes for the well-being and filling in gaps in welfare delivery by the government. Philanthropists fund disability welfare programmes and NGOs implement such programmes. This group of organizations also works towards building capacity of people with disability and other stakeholders in the area of disability rights awareness, providing insights into the lived realities in access to justice for people with disabilities and advocates for better implementation of rights and welfare schemes. This group of actors must be actively involved in the ODR ecosystem so that their programmes, interventions and advocacy strategies can take account of this new development in enhancing access to justice.

Group 3: Think Tanks, Academia: Think Tanks and academia should initiate research on ODR as a means of enhancing access to justice for people with disabilities, identify barriers to their success and propose models that will enable success. They should also have access to data (with due regard to data privacy sensitivities) and the body of research emanating from this group will inform laws and policies of Group 1 stakeholders, programmes and interventions of Group 2 stakeholders as well as products and innovations of Group 4 and 5 stakeholders.

Group 4: Private Businesses, Entrepreneurs, Technology Personnel: This group of participants are key to creating innovations that support and advance the implementation of ODR mechanisms. To be impactful, implementing ODR at scale is critical. This is possible as the business case for its success is seen and embraced by more and more groups. A diverse range of technology and other solutions under the ODR umbrella that are inclusive, and sensitive to needs of PwDs, would be necessary for the adoption of the system by persons with disabilities.

Group 5: Healthcare Professionals, Professional Counsellors, Peer Group Buddies, Persons with Disabilities Champions: Justice for persons with disabilities cannot be viewed in isolation from their socio-emotional state. Peer groups, buddies, mentors, professional counsellors and social spaces will aid persons with disabilities to access the right information, seek appropriate justice mechanisms and ultimately live with dignity.

Together the two parts: a core inclusive ODR system bolstered by responsive wrap-around systems comprising the five stakeholder groups will form an inclusive ODR system in which access to justice for people with disability can be guaranteed (as in Figure 7). Needless to say, the participation of PwDs should cut-across all dimensions of the ODR system, in all roles, truly espousing the ‘nothing about us without us’ ideology.

4.5 Law and Policy Considerations to Implement an Effective ODR

The following legislative and policy initiatives are needed to make ODR a viable justice-seeking channel for PwDs. This list is compiled based on inputs received at the consultation and in response to the existing constraints in accessing justice for people with disabilities. This list is neither exhaustive nor prescriptive and will evolve with the shifting needs of the people with disability:

Make ODR an opt-out model (i.e., parties opt-in to ODR by default).

The applicability of ODR must distinguish between grievance redressal and dispute resolution, so that ODR is an independent mechanism from grievance redressal systems such as those set up by online platforms and website.

Enable the integration of ODR infrastructure and process into the quasi-judicial role played by the Chief Commissioner for PwDs and the State Commissioner for PwDs envisaged under the Rights to Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016.

Enable the integration of ODR infrastructure and processes into the Sugamya Bharat App (‘Accessible India’ mobile application with a vision to create an inclusive barrier-free environment by identifying the barriers in built environment for persons with disabilities and facilitate their remedial by concerned authorities) and the Sugamya Bharat Abhiyan (Accessible India Campaign).

Incentivize the adoption of ODR in government and public service delivery by recognizing departments which resolve maximum number of disputes through ODR. When state instrumentalities such as public schools, public health centres, public works departments, etc., subscribe to the jurisdiction of an effective and disability accessible ODR system, this expands access to justice for people with disabilities.

Incentivize the adoption of ODR by the private sector, by opting to resort to ODR (in the instance of dispute between contracting parties instead of resorting to litigation through courts where permissible) in respect of disputes arising under contract as well as pre-contractual disputes.

Ensure that ODR processes are well defined and time bound, to ensure that dispute resolution is completed within a finite time period to ensure timely justice.

Make the parties bound by outcomes of the ODR (i.e., parties can enforce ODR decisions including by legal means). Currently, decisions passed by CCPD and SCPD in matters referred to them by people with disabilities are recommendatory in nature.

ODR must provide for clear appeal mechanisms and grounds of appeal, but simultaneously limit appeal to civil courts, similar to limited grounds of appealing arbitration decisions under India’s Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

Law and policies that pertain to ODR must consciously provide for capacity development and sensitization of its respective stakeholders to the needs, challenges and marginalization of persons with disabilities, towards building awareness, dispelling biases and reinforcing equity.

Laws and policies focused on the welfare of people with disabilities must also specifically provide for inculcating rights awareness, knowledge of entitlements and mechanisms to track the implementation of these commitments towards enhancing access to justice for people with disabilities.

Laws and policies for ODR must build in audit to track impact on people with disabilities. The technology that supports the ODR must be subject to audit along with ODR processes and outcomes.

-

5 Way Forward

With India’s legislative and judicial preparations to adopt ODR, steps must be taken at the design stage itself to bring in persons with disabilities on the ODR platform. We hope that this blueprint informs the creation of such inclusive ODR systems in the future. There will be value to pilot an ODR system built on this blueprint and use lessons to further strengthen the system in the future.

-

Annexure

Annexure 1: ADR-Related Laws in India

Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 followed by the 2019 and 2020 amendments which established the Arbitration Council of India and removed qualification requirements for arbitrators, respectively.

Section 89 of the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC) (1908) empowers the court to refer a case for resolution through one of the ADR modes recognized under the provision – arbitration, conciliation, judicial settlement, including settlement through Lok Adalat or mediation.

The requirement to set up Lok Adalats comes from the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 which provides for conciliation services through Lok Adalats.

Family Courts Act, 1987 – u/s 9, courts are required to encourage parties to arrive at a settlement before pursuing litigation. In K. Srinivas Rao v D.A. Deepa, the SC has said that mediation must be exhausted before pursuing litigation in the realm of matrimonial disputes.

SEBI (Ombudsman) Regulations, 2003 – Regulation 16(1) mandates the Ombudsman to attempt settlement of the complaint by agreement or mediation between the complainant and the listed company or its intermediary.

Commercial Courts Act, 2015: Section 12A provides for mandatory pre-litigation mediation.

Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (Model Bye-Laws and Governing Board of Insolvency Professional Agencies) Regulations, 2016 mandates establishment of the Grievance Redressal Committee by the Insolvency Professional Agencies to attempt redressal of grievances against professional members of such agencies through mediation.

Companies Act, 2013 and the Companies (Mediation and Conciliation) Rules, 2016 – Section 442 provides that the Central Government will maintain the “mediation and Conciliation Panel”. Any party is free to, at any stage of the proceedings before the Central Government, National Company Law Tribunal or National Company Law Appellate Tribunal, to have the dispute referred to mediation. Pursuant thereto, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs notified the Companies (Mediation and Conciliation) Rules, 2016.

Consumer Protection Act, 2019 (Section 74) provides for the establishment of Consumer Mediation Cells in every district. Chapter V also empowers parties to seek mediation at any stage of the proceedings. Under the Consumer Protection Act (E-Commerce) Rules, 2020, e-commerce entities are required to provide for an internal grievance redressal mechanism which is the foundation for setting ODR.

Industrial Relations Code, 2020 provides for the appointment of conciliation officers and conceives conciliation as the first level of dispute resolution whenever there is an industrial dispute or wherever it is apprehended.

Annexure 2: Technology-Related Laws in India

Section 65A and 65B of Indian Evidence Act, 1872 enumerates conditions for the admissibility of electronic evidence.

Section 4 and 5 of the IT Act, 2000 provides recognition to electronic records and electronic signatures.

Annexure 3: Judicial Precedents

Shakti Bhog v. Kola Shipping (2009) 2 SCC 134 and Trimex International v. Vedanta Aluminium Ltd 2010(1) SCALE574: Recognized online arbitration and online arbitration agreements through email, telegram or other means of telecommunication.

Grid Corporation of Orissa Ltd. V AES Corporation (2002) 7 SCC 736: Consultation of parties and appointment of arbitrators can also happen online.

State of Maharashtra v. Praful Desai225: Recording evidence and witness testimonies can be done through video-conferencing.

Central Electricity Regulatory Commission v. National Hydroelectric Power Corporation Ltd. (2010) 10 SCC 280: Recognized service of summons through online mode.

Cognizance for Extension of Limitation 2017 SCC OnLine Bom 1433: Court took matters in hand. Relaxed mandatory in-person appearances and removed the statute of limitation due to COVID-19 pandemic.

M/S Meters and Instruments Pvt. Ltd. vs. Kanchan Mehta, Suo Motu Writ Petition (C) No. 3/2020: identified that complete reliance could be placed on technology tools to resolve disputes. The court observed that some cases could partly or entirely be concluded ‘online’ and recommended the resolution of simple cases like those concerning traffic challans and cheque bouncing through online mechanisms.

Noten

- * Contributing Organizations: This report has culminated through a stakeholder session conducted by EnAble India and Pacta at the International Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) Forum (2023) organized by Agami in Bengaluru. The blueprint for an inclusive ODR for persons with disabilities was developed through expert consultations of Mr. Amar Jain, Ms. Jeeja Ghosh, Mr. Rajiv Raturi, Ms. Sanchita Ain, Mr. Taha Idrees Haaziq, Late Ms. Saudamini Pethe, Mr. Sunil Sahasrabudhe, Mrs. Pratibha Nakil and Ms. Shristi Gajurel at the International ODR Forum (2023). The roles of the contributing organizations were as follows: Pacta and EnAble India helped design and conduct the workshop session. EnAble India steered a team of experts from whose opinions the blueprint has been developed. Agami hosted the session and provided the requisite know-how on organizing the session. About Pacta: Pacta is a Bengaluru (India)–based boutique law and policy think tank dedicated to supporting civil society organizations, universities and non-profit initiatives. Pacta has an unflinching commitment to provide legal and policy consulting support for public service delivery. Acknowledging the crucial role of research and scholarship for social development, Pacta engages in law and policy research through self-driven and collaborative projects. Focus areas are – philanthropy, disability, education, gender and information technology.About EnAble, India: EnAble India is a non-profit organization working for the economic independence and dignity of persons with disability (PwDs) since 1999, impacting thousands of PwDs and stakeholders. Considered to be a pioneer in employability and employment of PwDs, EnAble India has catered to the needs of 21 disabilities and more. EnAble India impacted 325,000+ individuals, including persons with disabilities and their families in 28 states and 8 union territories in India. In the past 23 years, EnAble India has collaborated with 786 companies and 229 partner organizations across 1253 locations in 25 countries. They opened up 402 job roles across 34 sectors, built 12+ models and frameworks to train employable PwDs, and "includable leaders" capable of leading the change. EnAble India’s models and content are used across many organizations not only in India but also in Africa, Asia, Europe and America.

-

6 World Health Organization. (2023, March 7). Disability. WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health.

-

7 United Nations. (n.d.). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD). United Nations. http://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd.

-

8 United Nations. (n.d.). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD). United Nations. https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd#:~:text=There%20were%2082%20signatories%20to,1%20ratification%20of%20the%20Convention.

-

9 United Nations. (2020, August). International principles and guidelines on access to justice for persons with disabilities. United Nations.

https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2020/10/Access-to-Justice-EN.pdf. -

10 Beqiraj, J., McNamara, L., and Wicks. V. (2017, October). Access to justice for persons with disabilities: From international principles to practice. International Bar Association. https://www.biicl.org/documents/1771_access_to_justice_persons_with_disabilities_report_october_2017.pdf.

-

11 United Nations. (n.d.). Goal 16: Promote just, peaceful and inclusive societies. United Nations. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/peace-justice/.

-

12 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. (n.d.). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

-

13 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. (n.d.). SDG Indicators Metadata repository. Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/?Text=&Goal=16&Target=.

-

14 Flynn, E., Moloney, C., Fiala-Butora, J., and Echevarria, I.V. (2019). Access to justice of persons with disabilities. Institute for Lifecourse and Society. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Disability/SR_Disability/GoodPractices/CDLP-Finalreport-Access2JusticePWD.docx.

-

15 Larson, D. A. (2014). Access to justice for persons with disabilities: An emerging strategy. Laws, 3(2), 220-238. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-471X/3/2/220.

-

16 Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (n.d.) Toolkit on disability for Africa. Access to justice for persons with disabilities. United Nations. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/documents/disability/Toolkit/Access-to-justice.pdf.

-

17 The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act. (2016). Government of India. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15939/1/the_rights_of_persons_with_disabilities_act%2C_2016.pdf.

-

18 Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. (2011). C-21: Disabled population by type of disability, marital status, age and sex (India & States/UTs). Government of India.

https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/43468. -

19 Liasidou, A. (2013). Intersectional understandings of disability and implications for a social justice reform agenda in education policy and practice. Disability & Society, 28(3), 299-312. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09687599.2012.710012.

-

20 Mohit, A., Pillai, M., and Rungta, P. (2006). Rights of the disabled. National Human Rights Commission. https://nhrc.nic.in/sites/default/files/DisabledRights_1.pdf.

-

21 Ministry of Human Resource and Development. (n.d.). Access to justice. Access to justice and persons with disabilities. Government of India. http://epgp.inflibnet.ac.in/epgpdata/uploads/epgp_content/Law/02._Access_to_justice/10._Access_to_Justice_&_Person_with_Disability/et/5637_et_10ET.pdf.

-

22 Right to Education. (n.d.). Primer No. 3: Human rights obligations: Making education available, accessible, acceptable and adaptable.

https://www.right-to-education.org/resource/primer-no-3-human-rights-obligations-making-education-available-accessible-acceptable-and. -

23 Das, A. (2022). How the supreme court protected disability rights in 2022? LiveLaw. https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/how-supreme-court-protected-disability-rights-2022-217751?infinitescroll=1.

-

24 Tripathy, S. (2021, October 25). India must build, re-build its courts for disabled. Judicial infra key to justice delivery. The Print. https://theprint.in/opinion/india-must-build-re-build-its-courts-for-disabled-judicial-infra-key-to-justice-delivery/756058/.

-

25 The Legal Services Authorities Act. (1987). https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/19023/1/legal_service_authorities_act%2C_1987.pdf.

-

26 Ministry of Law and Justice. (2022, April 7). Legal aid to the disabled. Government of India. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1814545.

-

29 http://www.ccdisabilities.nic.in/resources/leading-orders-of-ccpd.

-

30 Disability Right through Courts. (2014, May 14). Delhi HC redefines the scope of powers of chief commissioner disabilities. https://www.disabilityrightsindia.com/2014/05/delhi-hc-redefines-scope-of-powers-of.html.

-

31 Ministry of Law and Justice. (2020, September 29). The industrial relations code. Government of India. https://labour.gov.in/sites/default/files/ir_gazette_of_india.pdf.

-

32 Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. (2020). https://consumeraffairs.nic.in/sites/default/files/E%20commerce%20rules.pdf.

-

33 Nalanda Judgeship. e-Court Mission Mode Project. https://districts.ecourts.gov.in/nalanda/e-court-mission-mode-project.

-

34 National Judicial Data Grid. (2020, December 31). https://njdg.ecourts.gov.in/njdgnew/index.php.

-

35 E-Courts Mission Mode Project. (2022, January 21). Case Information System Information Brochure. https://districts.ecourts.gov.in/case-information-system-information-brochure.

-

36 Supreme Court of India. (n.d.). Press release. https://main.sci.gov.in/pdf/Press/press%20release%20for%20law%20day%20celebratoin.pdf.

-

37 Ministry of Law and Justice. (2022, August 5). Promotion of e-Lok Adalat. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1848734.

-

38 High Court of Delhi. (2020). Digital NI Act Courts in Delhi. Project implementation guidelines. https://delhidistrictcourts.nic.in/DigitalNIActCourtsProjectImplementationGuidelines.pdf.

-

39 Supreme Court of India. (2003). The State of Maharashtra vs. Praful Desai. https://main.sci.gov.in/jonew/judis/19114.pdf.

-

40 All India Legal Forum. (2021). Legal fortnight. February Edition 1. https://www.nluo.ac.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Legal-Fortnight-Febedn-vol1.pdf.

-

41 Kinhal, D. et al. (2020). ODR: The future of dispute resolution in India. Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy & JALDI. https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/research/the-future-of-dispute-resolution-in-india/.

-

42 The NITI Aayog Expert Committee. (2021, October). Designing the future of dispute resolution. The ODR policy plan for India. NITI Aayog. https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2021-11/odr-report-29-11-2021.pdf.

-

43 The Mediation Bill. (2021). https://legalaffairs.gov.in/sites/default/files/mediation-bill-2021.pdf.

-

44 The Digital Personal Data Protection Bill. (2022). https://www.meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/The%20Digital%20Personal%20Data%20Potection%20Bill%2C%202022_0.pdf.

-

45 Sharma, N., Gupta, P., and Iqubbal, A. (2022). CUTS comments on the draft digital personal data protection bill. CUTS International. https://cuts-ccier.org/pdf/cuts_comments_on_the_digital_personal_data_protection_bill-2022.pdf.

-

46 Thomas, Z. (2022, January 28). What constitutes ‘dispute’ under arbitration & conciliation act? Madhya Pradesh High Court Explains. LiveLaw. https://www.livelaw.in/news-updates/madhya-pradesh-high-court-dispute-arbitration-conciliation-act-190521.

-

47 Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food & Public Distribution. (n.d.). Integrated grievance redressal mechanism. Government of India. https://consumerhelpline.gov.in/about-portal.php.

-

48 Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food & Public Distribution. (n.d.). Integrated grievance redressal mechanism: Convergence partners. Government of India. https://consumerhelpline.gov.in/convergence-partners.php.

-

49 Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances. (n.d.). List of nodal public grievance officers. Government of India. https://pgportal.gov.in/Home/NodalPgOfficers.

-

50 Google Play. Sugamya Bharat App. (2023, September 21). https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.geostat.sugamyabharatMOH&hl=en_IN&gl=US&pli=1.

-

51 Larson, D. A. (2020). ODR accessibility for persons with disabilities: We must do better. Online Dispute Resolution: Theory and Practice (2nd ed. Eleven International Publishers, Fall 2020 Forthcoming). https://deliverypdf.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=876127020083070018119021126084017098032032005076035071068096124022104024109097072123038034063030056048039112094092106013087118019016043042041101013012029071100100003073039013113003098001067013117012082115090117117075080025096018125125081102099101000&EXT=pdf&INDEX=TRUE.

-

52 Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. (2023, May 10). Notification. Gazette of India. Government of India. https://disabilityaffairs.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/RPwD%20(Amendment)%20Rules%2C%202023%20-%20Accessibility%20standards%20on%20ICT%20products%20and%20Services_compressed.pdf.

-

53 Chandola, B. (2022, May 20). Exploring India’s digital divide. Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/exploring-indias-digital-divide/.

-

54 Abhijith, S.R. (2020, December 28). Digital Disability Divide: A problem to address for an inclusive development [Post]. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/digital-disability-divide-problem-address-inclusive-development-s-r/?trk=public_profile_article_view.