Mobile Online Dispute Resolution Tools’ Potential Applications for Government Offices

-

1 Introduction

Nearly all jobs now involve some form of digital technology use, and it is normal for work-related relationships to be developed and maintained using digital tools.1xD. Lupton, Digital Sociology, New York, Routledge, 2015, p. 1-2. Digital technology use can simply mean that individuals communicate with each other using email, smartphones, social media platforms or other platforms designed for and within a specific organization. The field of dispute resolution has evolved alongside this use of digital technology. Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) is a relatively new and quickly evolving subcategory of dispute resolution. Research conducted to date is largely limited to ODR applications within e-commerce settings; however, a rapidly growing variety of scenarios now use ODR tools.

The data for this article was collected in the process of evaluating the potential impact of mobile ODR (MODR) tools on the dispute resolutions interventions provided to government clients. In order to determine how MODR tools could enhance the dispute intervention services currently provided to government clients, the research first explored several secondary questions:How receptive are government workers to the use of MODR tools?

How might ODR tools impact the relationship building aspects of dispute resolution?

What ODR tools currently on the market might address the needs of government workers?

Participants in this study had taken part in training provided by a private company whose services targeted conflict prevention and repairing damaged relationships to promote healthy and safe working environments. Interviews were conducted with clients from municipal and federal government offices in Canada and municipal and state government offices in Australia. This selection reflected the primary clientele of the company, but the findings of the study are potentially applicable to other recipients of dispute prevention and resolution training.

ODR is becoming increasingly relevant to workplace dispute and conflict prevention services as technological abilities rapidly advance and are applied in increasingly varied ways; however, academic research has struggled to keep pace with the realities of the field. Dispute resolution providers need to understand how ODR tools might impact the services they provide and how ODR could be applied to better meet the needs of their clients. This knowledge is necessary in order to provide their clients with the best services possible and to maintain a competitive edge in the delivery of dispute prevention and resolution services.

The development of ODR has generally been broken down into four phases.2xK. Mania, ‘Online Dispute Resolution: The Future of Justice’, International Comparative Jurisprudence, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2015, pp. 76-86; E. Katsh & J. Rifkin, Online Dispute Resolution: Resolving Conflicts in Cyberspace, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2001 . ODR is intrinsically connected to the Internet, and these phases have been heavily influenced by its evolving capabilities and applications.3xN. Ebner & J. Zeleznikow, ‘No Sheriff in Town: Governance for Online Dispute Resolution’, Negotiation Journal, Vol. 32, No. 4, 2016, p. 298. Mania described four phases in the development of ODR practice. The first phase, from 1990 to 1996, was a test period in which amateur applications of technology were applied to traditional dispute resolution practices. ODR application was limited to disputes generated in online interactions. Commercial ODR services were introduced in the second phase, from 1997 to 1998. During the third phase, from 1999 to 2000, companies began introducing electronic DR tools, and ODR became a viable business. The fourth and ongoing phase has seen the introduction of ODR to courts, administrative authorities and governments, as well as its continued use within the online community.4xMania, 2015, p. 77. This final phase recognizes the potential benefits of applying ODR to both offline and online-generated disputes.

There are two generations of ODR systems that are distinguished by their application of technology to the dispute resolution process. First generation ODR systems use technology to support a process in which human disputants remain the central generators of solutions. The second generation uses technological tools for idea generation, planning and decision-making.5xD. Carneiro et al., ‘Online Dispute Resolution: An Artificial Intelligence Perspective’, Artificial Intelligence Review, Vol. 41, No. 2, 2014, pp. 214-215. Essentially, first generation ODR systems treat technology as a supportive tool, while in second generation systems it has been integrated into the analysis and resolution process.

ODR products are rapidly becoming commonplace tools in the resolution of disputes and conflicts, regardless of whether they were generated online or offline. ODR tools have recently been introduced by the provincial governments of British Columbia and Ontario to aid in the resolution of select civil disputes.6xA. Jun, ‘Free Webinar Training: Strata Property Disputes & The Civil Resolution Tribunal’, [web blog], August 2016, http://blog.clicklaw.bc.ca/201/08/25/free-webinar-training-strata-property-disputes-the-civil-resolution-tribunal/ (last accessed 14 April 2017); I. Harvey, Inching Towards the Digital Age – Legal Report: ADR, [website], 2016, www.canadianlawyermag.com/6104/Inching-towards-the-digital-age.html (last accessed 26 February 2017); M. Erdle, Ontario Joins Wider Move Toward Online Dispute Resolution to Ease Court Burdens, [website], 2015, www.slaw.ca/2015/03/25/ontario-joins-wider-move-toward-online-dispute-resoltuion-to-ease-court-burdens/ (last accessed 19 February 2017). Governments around the world, including the European Union, have created legislation promoting the use of ODR tools, where ODR is applied to jurisdictional issues that have arisen out of cross-border uses of Internet technologies.7xD. Clifford& Y. Van Der Sype, ‘Online Dispute Resolution: Settling Data Protection Disputes in a Digital World of Customers’, Computer Law & Security Review, Vol. 32, No. 2., 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2015.12.014 (last accessed 28 May 2017).

As the use of online communication tools increases, it is understandable that there is concern about how they might affect human interactions. Trust-building exchanges that used to occur in person are now occurring entirely in cyberspace. In order to assess what kinds of MODR tools would be most useful to support the work done by those who provide dispute prevention and resolution services, it is necessary to understand the antecedents to trust that are inherent in online communication methods.

The application of ODR tools to disputes generated in online interactions has become well established through online venders, such as eBay’s platform, which, as of 2016, handles approximately 60 million cases a year.8xEbner & Zeleznikow, 2016, p. 319. Although research on the relationship between human interactions and online communication methods is limited, that which explores the development and maintenance of trust between parties who communicate, either entirely or partially, through online tools can be applied to the development of trust in MODR. Some research in this field is limited to the development of brand loyalty.9xA. Baranov & A. Baranov, ‘Building Online Customer Relationships’, Bulletin of the Transylvania University of Brasov. Series V: Economic Sciences, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2012, p. 15. Other studies have examined the broader relationship between ODR and trust, dialogue generation and relationship maintenance.10xC. Rule & L. Friedberg, ‘The Appropriate Role of Dispute Resolution in Building Trust Online’, Artificial Intelligence and Law, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2005, p. 184; W. Shin, A. Pang & H. Kim, ‘Building Relationships through Integrated Online Media: Global Organizations’ Use of Brand Web Sites, Facebook, and Twitter’, Journal of Business and Technical Communication, Vol. 29, No. 2, 2015, p. 184, http://doi.org/10.1177/1050651914560569 (last accessed 31 May 2017).

In order to understand how ODR tools might influence social factors of conflict and disputes, this article used an exploratory research design to generate qualitative data through interviews with individuals who participated in training provided by a single dispute resolution service provider. Data collected through interviews was analysed using a comparative thematic analysis model that supported the comparison of different interview responses to specific topics, while also allowing a holistic overview of the data set.11xU. Flick, Introducing Research Methodology, Los Angeles, Sage, 2015, pp. 184-185. Each interview was coded immediately following transcription and before subsequent interviews. Codes were constantly compared with other codes or categories.

The results of this study will be most pertinent to government offices. However, some of the findings of the study have potential applications for non-government offices and to individuals who have not received dispute resolution or prevention interventions. There were a variety of office environments present within the participant pool, and interviews largely addressed issues and experiences likely to occur in most office workplaces. -

2 Background

The field of ODR was first recognized as a practice area by the International Institute for Conflict Prevention and Resolution in 2012. While still in its infancy, disagreements about topics such as what should be included within the scope of ODR in general and what counts as computer mediated communication (CMC) persist.12xB. Davis & P. Mason, ‘Locating Presence and Positions in Online Focus Group Text with Stance-Shift Analysis’, in S. Kelsey & K. St. Amant (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Computer Mediated Communication, Hershey, PA, IGA Global, 2008, p. 365; Z. Cemalcilar, ‘Communicating Electronically When Too Far Away to Visit’, in S. Kelsey & K. St. Amant (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Computer Mediated Communication, Hershey, PA, IGA Global, p. 375; Ebner & Zeleznikow, 2016, p. 298. Owing to the ongoing evolution of computer technologies and the continuously changing ways in which we conceptualize and apply these tools to dispute resolution, disagreement about these and other topics is unlikely to dissipate entirely.

An online dispute resolution process will not be something that appears fully grown on a single date but rather something that evolves; not only in the capabilities that are built into it, not only in our use of it, but in how we think about it.13xKatsh & Rifkin, 2001, p. 11.

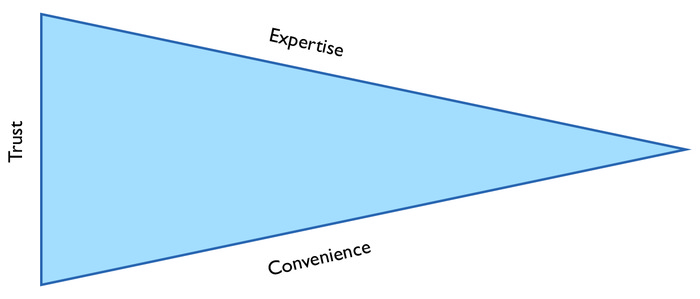

In their book Online Dispute Resolution: Resolving Conflicts in Cyberspace (2001), Katsh and Rifken outline three fundamental building blocks, namely convenience, trust and expertise that are required in any successful ODR system. They argue that there is no objective way to measure these factors that typically influence one another. This means that strengthening one building block may weaken another.14x Ibid., pp. 75-76. For example, if relying on an extensive amount of expert knowledge is required, the system may become more difficult for the average user to navigate. Such a tool would trade convenience for expertise. The authors contend that trust is often underestimated, but, owing to inherent difficulties with online identity verification, they consider it to be an uncontrollable factor.15x Ibid., p. 85.

Following the publication of the book, readily available video tools and pervasive practices of online discussion and communication have greatly mitigated this last concern. As a result, attitudes towards CMC have evolved to the point where trust is no longer uncontrollable. The role of trust and methods of influencing it are discussed later in this article.

Excluding the sources described earlier, most of the limited ODR literature is written from the perspective of organization-customer relations, with a strong focus on the establishment of customer loyalty.16xBaranov & Baranov, 2012, p. 15; Shin et al., 2015, p. 188. No literature was found that explicitly addressed the topic of relationship building between individuals in ODR scenarios. However, considering the relationship cultivation strategies present in the literature, many of the insights into online organization-customer relationships should be transferable to interpersonal relationship building.

Cemalcilar, who strongly supports CMC, notes that there are mixed attitudes towards its potential impact on social interactions.17xCemalcilar, 2016, p. 366. From one perspective, online communication blocks the reception of social and contextual cues, meaning that it is harder to establish and maintain relationships. From another perspective it is supplemental to social interactions, providing new options for communicating over great distances.

CMC is now a ubiquitous method of maintaining relationships, as demonstrated by the fact that interpersonal communication is a principal reason for the use of home computers. However, types of computer usage are linked primarily to generational factors, with younger users being much more likely to communicate extensively online than older generations.18x Ibid., pp. 365-366. This information indicates two things. First, CMC can be a powerful tool for relationship building through ODR/MODR. Second, differences in attitudes and comfort of use must be considered, especially if two parties’ approaches to online communication differ. Attitudes and comfort levels are different from computer illiteracy. They do not inhibit communication itself but may impact the information individuals are willing to share. These factors can also impact the way parties view relationships developed online as opposed to in person.

The literature indicates that despite high levels of online communication, ODR is underutilizing many forms of CMC. Online media provide great opportunities for two-way communication and relationship building, but organizations tend to underutilize them. It is more common to establish websites as a tool for information dissemination than for generating discussion.19xShin et al., 2015, p. 190. However, there has been a shift towards more interactive websites such as those used by Facebook and Twitter that have been designed specifically for two-way communication.

Web 2.0 or the ‘social web’ refers to the prevalent social media sites and social uses of the Internet.20xLupton, 2015, p. 9. Although research on this topic is minimal, there appears to be a correlation between levels of use and the importance of social media as a communication tool. The potential impacts of using or ignoring social media opportunities intensify as more people engage through social media platforms.21xShin et al., 2015, p. 191. Despite the adoption of social media, organizations tend to use it in much the same way they use websites, as a means of one-way communication.22x Ibid., pp. 184-185; K. Koehler, ‘Dialogue and Relationship Building in Online Financial Communications’, International Journal of Strategic Communications, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2014, p. 191, http://dx.doi.org/10/1080/1552118X.2014.905477 (last accessed 10 June 2017). These sites are not applying interactive components to aid in relationship development.

The types of tools used for online communication impact how messages are received. Video, text and images all have their own strengths.23xKatsh & Rifkin, 2001, p. 42. Video can simulate face-to-face interactions and allow body language to play a role in discussions. Text is useful for explaining complex ideas and can be used synchronously or asynchronously. Synchronous text communication enables real-time conversations, while asynchronous allows time for parties to think carefully about their responses. Images can help show patterns and changes in the discussions over the course of time.24x Ibid., p. 42.

The most effective combination of tools for an ODR system will depend on factors such as the context in which the system is used, the knowledge base of the users and the ideal desired outcome. Consider the three building blocks of convenience, trust and expertise outlined earlier. Systems with a focus on convenience could rely on images, while video and text could be more beneficial to transmit complex ideas (expertise). Videos of an expert or other significant individual could also be used to aid in the development of trust.

Increasingly widespread access to the Internet provides individuals with access to CMC tools from nearly anywhere and at any time. An International Telecommunication Union Report (2013) stated that nearly 100% of the global population now has access to a mobile phone signal and that the quality of accessible signals continues to rise.25xLupton, 2015, p. 118; International Telecommunications Union, ‘Measuring the Information Society’, 2013, p. 3, www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/publications/mis2013/MIS2013_without_Annex_4.pdf (last accessed 6 June 2017). Advances in affordable high-speed Internet has allowed for quality video connections for a number of years.26xInternational Telecommunications Union, 2013, p. 91. It is conceivable that video quality will continue to improve as future technological development increases both the signal speed and the number of available devices. Despite these developments, most online mediation relies on real-time text-based communication.27xMania, 2015, p. 79. This reflects the general consensus that ODR is not fully utilizing the available CMC.2.1 Establishing and Maintaining Trust Online

CMC tools have the potential to provide innumerable combinations of audio, visual and textual methods of communication. Combined with the range of attitudes and comfort levels experienced by users, this creates a highly complex environment with almost unlimited outcomes. Trust in online interactions can be defined as feeling confident that others will act fairly, respectfully, honestly and transparently.28xRule & Friedberg, 2005, p. 195. Trust exists only where the user perceives it to be present. In these complex environments it is necessary to monitor factors that can support or diminish trust in the experience of the user. The style of CMC tools must be able to convey messages between individuals in a way that is clear.

Rule and Friedberg, in their examination of the relationship between ODR and trust, argue that ODR is typically thought of as only a segment of an overarching trust-building strategy.29x Ibid., p. 193. They support the widely accepted idea that it takes time to build trust.30x Ibid., p. 195. Katsh and Rifkin also support this understanding of trust development, arguing that ODR itself should be applied as a trust-building tool for websites. Trust building begins with the user interface and requires the anticipation of questions.31xKatsh & Rifkin, 2001, p. 88; R. Ott, ‘Building Trust Online’, Computer Fraud & Security, 2000, p. 10, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1361-3723(00)02017-0 (last accessed 21 April 2017). Together, ease of use and readily accessible information for common questions make the system useful to users and create a sense of reliability on the part of the system provider. The authors maintain that trust improves when a website demonstrates a willingness to resolve issues through easily accessible ODR methods. The existence of an ODR tool does not imply to users that the system is problematic but rather that it signals a willingness to work with users to resolve any issues that may arise. This form of trust building assumes that disputes occurring online, typically related to e-commerce, are being resolved using ODR. While this project is not examining ODR for e-commerce applications, it would be remiss to dismiss the insights gleaned from this type of application.

Although studies relying on empirical evidence are scarce, examples of trust development can be found in numerous online communities. A study conducted using American statistics for online health communities found that developing trust online relied on the users’ ability to see the other’s point of view, display empathic concern and a belief in their own ability to reach a solution.32xJ. Zhao, S. Ha & R. Widdows, ‘Building Trusting Relationships in Online Health Communities’, Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, Vol. 16, No. 9, p. 652, http://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0348 (last accessed 14 April 2017). This same study emphasized the importance of cognitive and affective trust in online relationship building, which confirmed past research.33x Ibid., p. 654.

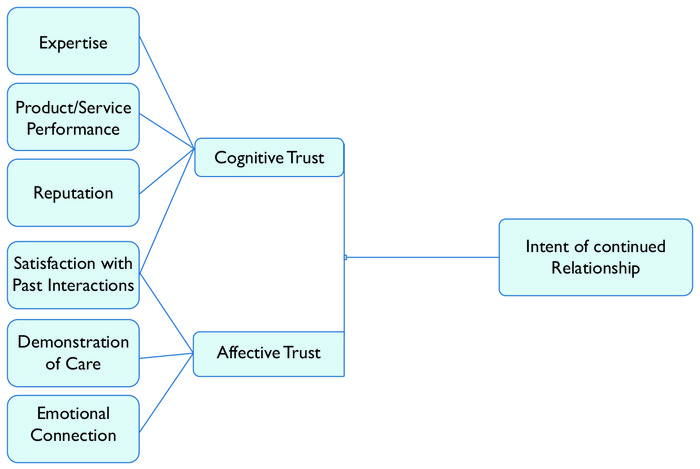

Empirical research on interpersonal trust and its antecedents in the fields of psychology and sociology describe interpersonal trust as a combination of cognitive and affective trust.34xS. Webber, ‘Development of Cognitive and Affective Trust in Teams: A Longitudinal Study’, Small Group Research, Vol. 39, No. 6, 2008, p. 746. The two types of trust are intrinsically linked but distinct from each other.35xD. Johnson & K. Grayson, ‘Cognitive and Affective Trust in Service Relationships’, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 58, No. 4, 2005, p. 505, https://doi.org.10.1016/S0148-2963(03)00140-1 (last accessed 16 June 2018). Cognitive trust is the confidence or willingness to rely on the other party. It requires a belief in their competence and reliability.36x Ibid., p. 501. This type of trust typically relies on reputation or past personal interactions with the other party. Affective trust, on the other hand, relies on emotional connections. Feelings of security, a perceived strength of relationship and demonstrations of care by the other party are antecedents to affective trust.37x Ibid..

Within interpersonal relationships, cognitive trust typically emerges first, while affective trust develops over time.38xWebber, 2008, p. 749. The development and maintenance of both cognitive and affective trust best support ongoing relationships. Antecedents of trust necessary to support ongoing relationships can be identified and nurtured (see Figure 1).

It is important to think about the process of trust development when building relationships through online tools, particularly when these relationships are part of an ODR process. In order to create opportunities for trust to develop among users, its antecedents must be identified and built into the ODR system. Identifying these factors can assist in developing and determining the most successful ODR tools for differing scenarios.Antecedents of Trust in Ongoing Relationships

2.2 Online Dispute Resolution Tools on the Market

Tyler’s 2004 assessment of the state of ODR found that of the 115 providers identified, 82 were still operating at the time of publication.39xM. Tyler, 115 and Counting: The State of ODR 2004, Melbourne, International Conflict Resolution Centre, 2004, p. 3, www.mediate.com/odrresources/docs/ODR%202004.doc (last accessed 19 January 2017) Tyler argued that, considering the ‘experimental nature’ of ODR as a field, this demonstrated the durability of these services. A survey conducted by Suquet et al., in 2010, revisited the providers listed in Tyler’s study as part of their own assessment. They found a total of only 34 ODR providers on the global market, a pool only 29.5% of the size of the one published by Tyler six years earlier.40xJ. Suquet et al., ‘Online Dispute Resolution in 2010: a Cyberspace Odyssey?’, 2010, p. 3, http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-684/paper1.pdf (last accessed 26 May 2017). While the low costs of ODR have been touted by most of its advocates as a major benefit, it has also been argued that the decrease in ODR entities post 2000 is related to the high costs of system design, creation and security maintenance.41xMania, 2015, p. 78. The majority of providers currently active operate with a generic scope (over 65%), and their primary dispute resolution mechanisms are mediation (74%) and arbitration (>40%).42xSuquet et al., 2010, p. 4. It is common practice for businesses to adapt technology created externally in order to fulfil their specific needs.43xU. Dolata, The Transformative Capacity of New Technologies: A Theory of Sociotechnical Change, 2014, London, Routledge, p. 11. While this is often sufficient for basic communication needs, dispute resolution-specific systems could provide specialized processes to aid in the generation of solutions and the nurturing of relationships. Information gathering and added security to protect data could also develop. These benefits that the literature hints at are not yet present.

A minority of the providers discussed by Suquet et al. allowed users to select their preferred resolution mechanism. Some of these mechanisms used multistep processes in which the level of system intervention increased if parties were unable to reach resolution.44xSuquet et al., 2010, p. 4. Expert systems such as these, created in consultation with experts in a field, provide non-expert users with specialized information. They enable large numbers of people to affordably access knowledge that would otherwise be expensive or difficult to reach.

It is important to emphasize that – as of 2014 – the design of most technology used for dispute resolution has been for general communications and information-handling purposes.45xD. Rainey, ‘Third Party Ethics in the Age of the Fourth Party’, International Journal of Online Dispute Resolution, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2014, p. 42; A. Stuehr, 8 Top Mobile Apps for Mediators, [website], 2013, www.mediate.com/articles/StuehrA1.cfm (last accessed 26 February 2017). One example of this is the Virtual Mediation Lab – Online Mediation Made Simple project. It is a resource for commercial, family and workplace mediators that hosts classes on how to conduct mediations through videoconferencing. The project also offers free webinars exploring online mediation and related topics.46xG. Leone, Home, [website], 2008, www.virtualmediationlab.com/ (last accessed 26 February 2017). This project is merely transposing traditional ADR into Internet-based communication platforms. While this can save costs by eliminating the need for space rentals and travel, it does not provide any further technology-related benefits.

As technology develops that is designed specifically for the delivery of ODR and MODR, new possibilities will emerge. These may range from the mere provision of access to the most relevant information and referrals to applicable services to the development of algorithms and the use of artificial intelligence to actively aid in reaching resolutions. Dispute resolution-specific platforms are on the market but have faced two significant challenges to widespread success. They are either proprietary in nature or have not gained sufficient users to remain commercially viable.47xRainey, 2014, p. 42. Proprietary systems include organizations’ internal dispute resolution systems. Daniel Rainey, Chief of Staff for the National Mediation Board (United States of America), claimed in the first issue of the International Journal of Online Dispute Resolution that these issues are slowly disappearing as computer illiteracy rapidly diminishes. Extrapolating from Rainey’s comment and Katsh and Rifkin’s earlier predictions, it would appear that individuals will become increasingly willing to participate in ODR/MODR processes as they become accustomed to engaging in interpersonal interactions through digital portals, both socially and at work. Adopting ODR tools as part of an organization’s formal or informal dispute resolution system is not unusual in today’s world.

The move away from proprietary systems to external ODR/MODR providers is important because of the issue of neutrality. Dispute resolution systems created, funded and operated by an organization may develop biases in favour of the organization in their processes and decisions.48xB. Davis, ‘Disciplining ODR Prototypes: True Trust through True Independence’, in A. Lodder et al. (eds.), Essays on Legal and Technical Aspects of Online Dispute Resolution, Amsterdam, Centre for Electronic Dispute Resolution, 2004, p. 83. In an article for the Centre for Electronic Dispute Resolution (Amsterdam), Benjamin Davis argues that not enough has been done to ensure ODR processes remain independent.49x Ibid., p. 75. Ensuring independence and freedom from bias is especially important if the use of the ODR system is encouraged or even enforced by the organization. The creation and use of independent ODR/MODR tools can help prevent risks associated with biases and conflict of interest.

The number of ODR services available to the public has fluctuated significantly since the late 1990s. Many of the services available in the early 2000s were merely digitized ADR. Services marketed as ODR-specific tended to target mediators and were primarily technologies for document sharing or videoconferencing. Within the last five years, tools designed specifically for ODR and MODR have begun to emerge, most notably the self-help guides found in the BC Property Assessment Appeal Board and the CRT’s Solution Explorer.50xD. Thompson, ‘The Growth of Online Dispute Resolution and Its Use in British Columbia’, 2014, Victoria, Continuing Legal Education Society of British Columbia, www.cle.bc.ca/PracticePoints/LIT/14-GrowthODR.pdf (last accessed 12 August 2017); Civil Resolution Tribunal, ‘How the CRT Works’, Civil Resolutions BC [website], 2017, https://civilresolutionsbc.ca/how-the-crt-works/ (last accessed 16 April 2017). These systems also demonstrate a shift beyond ODR to MODR.

Inhibiting attitudes towards CMC-supported relationships are becoming increasingly rare, although differences in technological comfort levels warrant consideration in multiparty interactions. Despite this, ODR is underutilizing the available technology. If a CMC technology is generic, its ODR applications may not be recognized. If it is proprietary, then its usership is obviously limited.

The literature supports the idea that ODR systems can be useful trust-building tools. Attitudes towards the use of CMC in relationship building are overwhelmingly positive, with the exception of recurring concerns regarding privacy. A lesser mentioned but equally important concern is the issue of neutrality, specifically for proprietary systems. External providers would be an excellent solution to this issue if they could become fiscally sustainable – something services have struggled with in the past. -

3 Findings

When invited to discuss their own experiences in the workplace, participants presented a wide range of exposure to and comfort with CMC. While online communication was used across the board, it was often being narrowly applied. Many descriptions provided by participants in the study mirrored the statements made in the literature regarding the widespread underutilization and unrealized potential in ODR-capable technologies. At the same time, many participants, perhaps because of their interest in dispute resolution, provided keen insights into how their own offices as well as other dispute resolution services providers could integrate modern technology into their dispute resolution and prevention practices to more fully realize the potential of ODR.

Although the primary medium of online communication listed by participants was email, they also reported using other platforms such as instant messaging, videoconferencing and Skype, Slack, WebEx, official department websites and the social media platforms Facebook (both official and unofficial group pages), Instagram, LinkedIn and Twitter. The participants’ experiences and opinions about conducting their work, developing and maintaining trust and building relationships with these tools were explored during interviews. By examining what features of these platforms they have found useful or harmful to the dispute resolution process or ways in which they have triggered or exacerbated disputes, the researcher was able to determine what aspects of a potential MODR platform would be most beneficial to their clients.

When designing this project, the researcher expected most conversation about communication to centre on experiences participants had had with their colleagues – internal communication. Owing to the diverse roles held by participants within a broad variety of departments, many participants spoke of instances in which they were communicating with individuals outside the employ of their offices – external communication. These individuals were either members of the public or employees of other government or private sector offices with whom the participant interacted in their work role. Most, but not all, participants spoke to varying extents on both internal and external communication. Eight participants discussed internal communication practices and experiences, and seven participants discussed external communication practices and experiences.

The data coding process resulted in six topics, which will be discussed in this section. Clients’ receptivity and opposition to MODR and ODR tools will be presented and their experience with ODR addressed. All participants made a point of discussing their concerns regarding weaknesses of CMC. The impact that online communication has had on relationship building and trust development will be highlighted. Finally, features that participants would like to see in a potential MODR tool and what they would like to get out of an education-oriented tool will be presented.3.1 Receptivity to ODR/MODR Tools

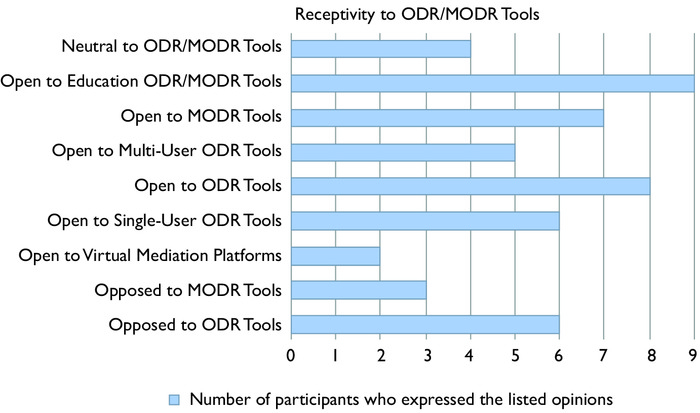

Receptivity to ODR/MODR Tools The numbers represented in Figure 2 demonstrate that some participants expressed conflicting opinions about their receptivity and opposition to ODR and MODR tools. If an individual noted multiple opinions, for example being receptive to ODR/MODR tools and being opposed to ODR tools, both opinions were coded and graphed. Participants’ willingness to use an ODR/MODR tool for some purposes but not for others accounts for these conflicting opinions. These opinions will be reflected throughout the findings. For example, some participants who welcomed the possibility of an education-oriented tool were reluctant to apply any form of ODR tool to relationship building and trust development.

The numbers represented in Figure 2 demonstrate that some participants expressed conflicting opinions about their receptivity and opposition to ODR and MODR tools. If an individual noted multiple opinions, for example being receptive to ODR/MODR tools and being opposed to ODR tools, both opinions were coded and graphed. Participants’ willingness to use an ODR/MODR tool for some purposes but not for others accounts for these conflicting opinions. These opinions will be reflected throughout the findings. For example, some participants who welcomed the possibility of an education-oriented tool were reluctant to apply any form of ODR tool to relationship building and trust development.

All nine participants responded that they would be interested in introducing some form of ODR or MODR tool to the services they receive from their dispute intervention provider. Two participants stated that they viewed online communication, primarily between their office and the public, to be the source of the problems they were looking to address through an ODR tool. Eight participants expressed a general interest in knowing what types of ODR tools were available and cited this as a driving factor in their participation in the study.

Four participants expressed interest in multiple styles of tools (specific descriptions of tool features can be found later in this article). Four participants stated that they would use a multi-user synchronous tool to bring individuals together in real time to resolve disputes. These individuals engaged in long-distance dispute resolution processes using various combinations of videoconferencing/Skype, teleconferences and emails; frequency of long-distance processes ranged from weekly to monthly to only occasionally.

Five participants clearly described tools that would be accessible to individuals as needed and that would provide them with advice for communicating and working through disputes they encountered in the workplace. These were coded as individuals who were open to single-user tools. A second group of individuals, which overlapped somewhat with the first, were open to ODR/MODR tools focused on education. Individuals in both groups related to the in-person training offered by the dispute intervention service provider. Finally, two participants expressed interest in a tool that could host virtual mediations; one wanted to address disputes involving parties in different geographic locations, and the other wanted to bring in mediators and other specialists not employed by their offices.

While every participant was open to using some form of ODR/MODR tool, six individuals expressed a reluctance to use tools in certain situations. These opinions register in Figure 2 as those who are opposed to ODR tools. It is important to register the significant level of opposition to ODR tools because it speaks to the concerns clients have with their use. However, it is equally important to note that one hundred percent of the participants who voiced opposition to the use of ODR and MODR tools also discussed scenarios and applications in which they were actively interested in pursuing the use of ODR/MODR tools.

There were repeated assertions that participants did not want online tools to replace any in-person training currently provided to their offices. Online tools were welcome only if they were supplemental to these services. Four individuals made a point of stating that they were opposed to ODR tools specifically in the context of mediating disputes; two of these participants cited past experience with inadequate devices, set-up and Internet connections as the chief cause of their reluctance to use virtual mediation set-ups in the future. In these instances, the use of online communication tools hindered the dispute resolution process by interrupting the flow of conversations due to lags or glitches. Audio-visual distortions and delays in entering or leaving caucuses were cited as having a dramatic impact on the effectiveness of the mediations.

Two individuals who worked in the same office were emphatic that they viewed online communication between government office workers and the public as being the cause of their problems, stating: “The online stuff isn’t the solution but the problem and what are our solutions to help our staff deal with that?” Although these participants were clear that they viewed online interactions to have a high potential for antagonistic interactions, they were nevertheless curious to explore what ODR or MODR options might have the potential to help address the issue. A total of four participants reported instances where they viewed CMC as problematic, either because of technological deficiencies or because anything less than face-to-face was considered insufficient (see Figure 3).3.2 ODR Experience

Data gathered from the literature review suggested that it was not uncommon for individuals to fail to recognize ODR experiences they have had. Six out of the nine participants in this study reported that they had no experience in using any form of ODR. Of those six participants, only three discussed activities that this study considers to be online dispute resolution practices, while self-reporting that they had no ODR experience. The majority of participants in this study both worked in roles that involved elements of dispute resolution and had an interest in the field of ODR. Participants in this study were therefore perhaps more likely to be able to accurately self-report their level of experience in using ODR than were the individuals reported on in the literature review.

Three participants responded that they had used ODR tools as part of their current job, although one individual revealed that owing to budget cuts their office was no longer able to sustain any ODR structures. Their experience with ODR was varied and included interpersonal communication training videos, virtual mediation chat rooms, videoconferences to conduct long-distance mediations, and pre- and post-mediation online document sharing. Another two individuals – who work at the same office – shared that their department has developed an app that will enable the public to express concerns and track the progress of their complaints. This app is expected to be in operation in the near future and will be the only example of an MODR tool in use by the participants of this study. Two participants reported that they did not use ODR in their current roles but that they had had very positive experiences using such tools in previous, non-government jobs. Six participants described instances where they had used ODR in relation to their current role; however, not all of them realized that the way they were using technology could be considered ODR. Of the three participants who did not use any form of ODR, two had past experience, and only one individual had no reported experience with ODR.

One participant who had extensive ODR experience in their current role no longer used ODR at the time of the interview. This participant described a pilot project their department had run that provided a text-based virtual mediation system that was accessible from any location and that was controlled by a mediator in their office.It was an experiment that worked but because I didn’t have the full support of the management we just let it go and went to the old traditional teleconference or face-to-face.

3.3 Weaknesses of Online Communication

While all participants described scenarios in which the benefits of online communication outweighed any potential weaknesses, every participant discussed their concerns with technical deficiencies of online communication. Deficiencies in the abilities of online communication methods impacted the experiences of every participant but did not typically dissuade them from continuing to use some form of CMC for the purposes of dispute prevention and resolution. Participants introduced weaknesses in a number of ways. They were discussed as triggers for disputes, as causations of dispute escalation and as hindrances to dispute resolution processes. Although ODR tools that included video-based communication appeared to reduce the drawbacks of CMC, for some participants nothing could replicate the gravity present within in-person exchanges, Improvements in online communication practices and set-ups were still desired even when ODR methods were the de facto approach to resolution.

Obviously, the experiences and opinions presented here are subjective to the individual. For instance, one participant noted that parties in a dispute resolution process tended to be less pleased using a videoconference to host mediations than they were when physically present in the same space. Another participant reported an entirely different opinion, stating that in their experience hosting a text-based virtual mediation could be a very good forum for dispute resolution. Despite being without visual communication tools, they were happy to see the language and were able to participate fully. Weaknesses appeared to be subjective to the needs of the situation, and what was insufficient for the purposes of one participant could be considered successful by another.

Differing standards of devices and Internet connections have also been an issue for those who attempted to deal with disputes using online communication. Even in instances that were considered generally successful, the strain of operating the technology could sometimes be considered too great an effort to maintain long term. In the case of the participant who had successfully operated a virtual mediation pilot programme, they still claimed that:It was hard to get running because of the different types of equipment and it faded away. I didn’t pursue it because our workload went up and we had to get cases done. So we don’t do that now.

This demonstrates that the weaknesses and challenges of online communication can easily outweigh the benefits. The equipment used to access the virtual mediation platform was not uniform. Such inconsistency is unsurprising as users of the platform had different working locations and employers. At the same time, in instances where disputants are at a significant geographic distance, some method of long-distance mediation is highly desirable owing to the time and cost saving potential.

The use of email was expectedly ubiquitous to the work of all study participants and was typically the first answer provided after they were asked how they used online tools to communicate with their colleagues. Email was used for starting the dispute resolution process, setting up meetings and documenting agreements made in person. As a text-only form of communication that does not allow for facial expressions or tone to influence the perceptions of the receiver, email held a high risk of creating or nurturing misunderstandings. Blocking the reception of social and contextual cues was one of the drawbacks of CMC noted in the literature review. Participants also noted that when using email “it is easy to get misconstrued. You might mean it in a different way than how the person took it”.

Regardless of these drawbacks, email was necessary to the work of the participants. One participant reported a practice they had successfully introduced to their department:One of the things that I’ve adopted is emojis because that gives you some of the tone. So you can say something but put a smiley face at the end of it and they’re not going to take it serious.

This participant reported that the practice of including emojis in email communication had a large and positive impact in the office workplace and aided in the avoidance of misinterpretations and that some colleagues working in leadership roles have adopted the practice.

Although the downsides of online communication were discussed in each interview, it was recognized that such methods of communicating are an intrinsic part of the working environment.And if there was a quick, effective way of circumventing or mitigating risk around misunderstandings, inevitable conflict when a contentious issue arises, I would be keen to explore that. Because it is labour intensive.

The ‘it’ this participant was referring to was the process of dealing with issues using online communication, particularly in situations where a miscommunication had exacerbated the problem.

Concern about the weaknesses of online communication practices was the most frequently raised topic across all participant interviews. However, in most instances these concerns manifested as a desire for higher quality, easier to use tools. The quotes provided in this section demonstrate that despite concerns about misunderstandings, technological glitches or the effort of maintaining a system, online communication tools continued to be used in all offices.3.4 Relationships and Trust

The study participants discussed topics of relationships and trust together, and this section will address them jointly. Unsurprisingly, trust was considered a necessary antecedent to relationship building. The antecedents to trust being developed and maintained online differed slightly among the participants, yet generally conformed to the findings of the literature review in that the development of interpersonal trust typically occurred gradually over a period. Some, but not all, participants reported that when they communicated with people using CMC over long periods they developed similar trusting relationships to individuals with whom they shared workplaces.

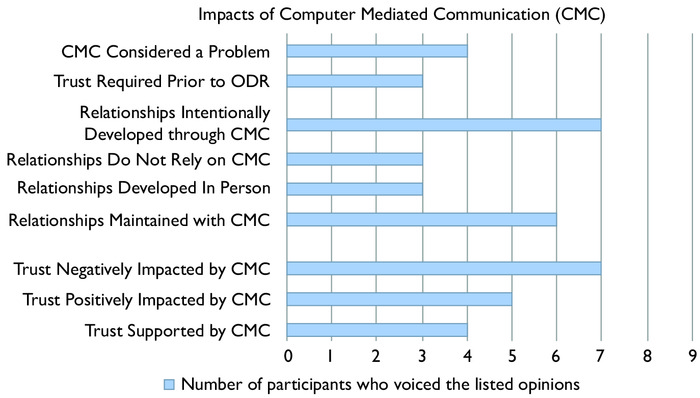

Attitudes among the participants in regard to the impacts of CMC on relationships and trust were mixed, in alignment with what was found in the literature review. Perceptions of CMC’s impact across the spectrum from positive to negative were linked to participants’ personal experience as well as to the culture of their work environment. In some instances, participants provided multiple answers to a question owing to the varied types of relationships they have with those they interact with at work. These multiple answers are reflected in the data of Figure 3. For example, a participant may have had relationships intentionally developed through the use of CMC and relationships that did not rely on CMC. When reflecting on a collection of different experiences, a participant may refer to times when trust was negatively impacted and other times when CMC usage had a positive impact on the experience. Both of the experiences were worthy of discussion and consideration, as it was likely that participants and other clients of the dispute intervention and prevention service provider would encounter similarly varied experiences in the future of their work.Impacts of Computer Mediated Communication (CMC)

Seven of the nine study participants presented examples of intentional relationship development. Internally, these included relationship development between a conflict resolution practitioner and colleagues, where individuals were introduced during training sessions and relationships were built and maintained through email, videoconference and phone. Fostering a sense of camaraderie in the workplace was also supported by public recognition of good work in group emails. External relationship development examples included communicating with the public on social media, correcting misinformation and providing a face for the department/office to establish a trusting relationship.

It was in the development of these relationships that participants reported positive impacts of CMC on trust. For instance, two participants reported that creating trusting relationships with the public meant that “they tend to cut us a bit of slack – they wouldn’t necessarily jump to the worst conclusion immediately”. Quick, accurate response to public requests for information enabled offices to build credibility. This allowed the dialogue to remain open, furthering the development of stronger trust and preventing disputes from escalating into conflicts. Positive impacts of CMC on trust were reported for both external and internal communication.

When reporting a negative impact on trust, participants spoke of specific instances of conflict where they had experienced an escalation of an already present dispute. Participants referenced misrepresentation in emails that occurred either innocuously or as a result of individuals in conflict who are “looking for a reason for it to be wrong”.

Participants who had worked in a coaching or mediating role reported negative impacts of videoconferencing such as a lessened ability to influence discourse through eye contact and general body language due to the set-up of office videoconferencing equipment. Large boardrooms where individuals were at a distance from the camera and screen were reported as being less easily guided through the mediation and more likely to be distracted by passer-by.

In one example, a dispute resolution practitioner was brought in by videoconference to mediate a dispute between two employees. However, owing to limited resources both disputants were initially placed in the same conference room. A power imbalance existed between the disputants that began to manifest and interfere with the mediation, which subsequently had to be rescheduled so another conference room could be borrowed and the disputants separated. One participant suggested that mediations be conducted via a system like Skype, which provided visuals that allowed for a focus on eye contact and facial expressions.

Participants presented a variety of opinions to explain how the impact of CMC on relationships was neutral. They argued that factors influencing the success or failure of an online interaction originated in, among other things, the attitudes of individuals or the state of pre-existing relationships between parties. The medium of communication was deemed irrelevant. Participants provided examples that demonstrated this neutrality. “The online works if you have very professional, respectful people”. Those who reported a neutral view of the impact of CMC tended to report experiences in which individuals had established a trusting relationship prior to ODR interventions.

Describing dispute resolution processes conducted online, one participant shared that they considered one-on-one interactions using CMC to be fine but that when working with multiple groups it became increasingly difficult. They did not have a visual connection with the individuals or parties. For this participant, CMC-hosted mediations were a frequent part of their job. Another participant claimed that in developing trust between individuals, video is the most important aspect of an ODR tool. Video-capable CMC tools allow individuals to create an approximation of face-to-face conversations. The communication tool brings people together as if they were in the same room. It does not add any value to the interaction, and when it works correctly, it does not diminish the exchange.

Three participants shared the view that ODR tools were informal and consequently depended on a previously established trust relationship. In this view, CMC does not negatively impact trust, but the sense of informality during CMC-hosted discussions makes it difficult to establish that kind of relationship. Those who reported that their working relationships existed prior to CMC usage had a hundred percent overlap with those who did not use CMC to maintain relationships.

Many of the nuances in relationship maintenance and development practices were attributed to the culture of the workplace that differed between interviews. All participants reported using some form of CMC during some stage of the dispute resolution process, and five participants reported having used online tools to communicate during a mediation situation. The work environment more heavily influenced the extent to which CMC is applied to active disputes than the employee’s personal preferences. For example, one participant who had substantial experience resolving disputes through CMC tools in a past job was asked by colleagues to always conduct in-person conversations as that was the practice of the office. There was no office policy against using CMC for dispute resolution, but the culture of the office rejected its use in delicate or tense situations.3.5 Desirable Features for MODR Tools

Study participants described a variety of hypothetical uses for an MODR tool or system they could use in their work. The traits described in this report are desired features that were described by multiple participants. Multiple participants independently introduced some features, while the researcher introduced others to gauge the level of interest in features that emerged in earlier interviews.

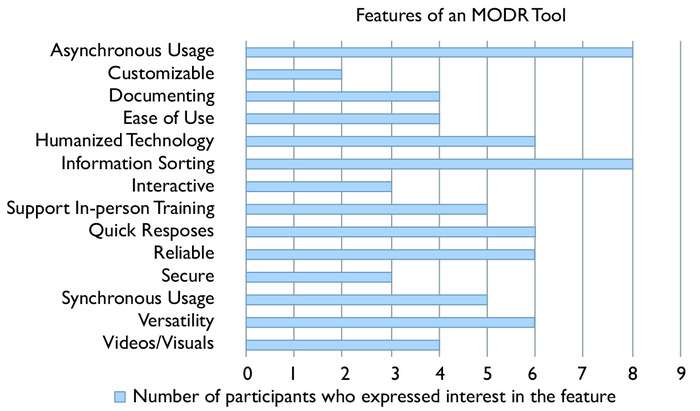

Certain concepts that arose in the interviews conformed to the commonly described factors of ODR systems as described by the reviewed literature. For example, four participants were attracted to ODR/MODR for its ability to document expectations and agreements leading up to and following mediation. The ability to provide quick responses to queries or conversations was attractive to six participants. These features, in particular, matched the features of ODR considered most desirable by the published literature.Feature of an MODR Tool

In addition to these two features, participants listed numerous features that they would like to see specifically in an MODR tool that the dispute prevention and intervention organization might provide as part of their future services. Features that only one participant expressed interest in were not included in this report as they were not considered representative of the client base. The full list of significant features that emerged from the interviews is displayed in Figure 4.

Asynchronous usage referred to an MODR tool that clients could access at any time. There was substantial overlap of this feature with the features labelled information sorting, interactive and support in-person training. Information sorting refers to a tool that could provide easy access to information; the information hypothesized by participants ranged from office dispute resolution procedures to communication tips to where to go or whom to contact for various issues. Participants were interested in having a tool that could help bridge training. The level of interest in this capability was extremely high and will be explored in the next section.

Humanized technology was a feature of ODR that was not explicitly stated anywhere in the academic or non-academic literature reviewed for this project. Humanized technology refers to the attempt to foster a sense of interpersonal communication when that communication is occurring online. Participants who described successful attempts at online relationship development spoke of ways in which they personalized interactions. This included providing their name and/or their face to the person who had reached out to their office online or to those to whom they were attempting to reach. It meant setting up online mediations in such a way that disputants were within arm’s length of the camera to create a sense of collaboration and to improve engagement. When participants discussed what they would like to see in an MODR tool, humanized technology meant demonstrating who they were, what can be expected of them, as well as fostering a sense of community among the users. By humanizing the technology, a sense of trust can begin to be established. In synchronous tools, it would aid relationship development by promoting users to engage as if they were entering into a discourse in person.

Synchronous usage features were discussed in relation to active virtual mediations or to training seminars in which clients could access the tool as part of the training. While five participants discussed this feature, most did not place as much emphasis on it as they did on asynchronous usage. Another feature that was described in general terms was versatility. Versatility had multiple meanings to different participants. They appreciated that technology could provide them with ‘agile ways of working’ that could ‘catch essential information quickly and reliably’. Three participants’ offices were already using devices such as laptops and tablets to allow for flexible work and communication practices. Participants wanted a tool that was multidimensional; particularly when speaking of education-oriented tools, they described something with a mixed media approach, using visuals and interactive elements to support multiple learning styles.

The issue of security features inherent in a potential MODR tool was not raised often in interviews. This is worth noting as it was not in line with evidence from the literature that suggests security features would be a crucial point for many users of ODR. Questions did not directly ask about participants’ thoughts on security, but when describing what was important to them in an MODR tool, only two participants discussed the subject.3.6 Education Tools

What I find is that everybody goes to the training, they think it’s really good and then you go back to your regular day-to-day lives and you don’t necessarily transfer the knowledge. So, I think that when you develop a program that keeps the information fresh, I think that’s beneficial.

The sentiment of this quote was repeated throughout all interviews. Multiple participants, beginning in the first interview, introduced the idea of using an MODR tool for the purposes of dispute prevention and resolution training. All participants either introduced the topic themselves or were prompted by the researcher to explore their views on using an MODR tool for education. Unlike the previous topics being addressed, the participants had a fairly unified approach to an education-oriented MODR tool. Many aspects of an MODR education tool were addressed earlier, particularly in the discussion of desired MODR tool features.

Primarily, an education MODR tool was viewed as something to be introduced alongside live dispute resolution and prevention training. Most participants were attracted to the idea of using the tool to create a bridge between the knowledge and skills taught during the seminars and the everyday workplace applications. Three participants were open to the idea of making an MODR tool available to their employees prior to training sessions as a means of orienting them to the subject matter, in addition to receiving a post-training support tool.

Participants identified two potential uses for an MODR education tool. First it would keep information fresh in the minds of the clients who could asynchronously access the tool when they needed a reminder of what was taught. One participant described their ideal tool as an ‘app to remind me, to help [clients] navigate something that they might not want to bring to HR, to build their skills and to provide them with some supports.’ Second, participants described a desire for clients to be able to use the tool to build upon their skills, either by working through hypothetical scenarios or researching communication or dispute resolution techniques. Ease of use and versatility were key points in the discussions of an education tool.

Another participant described a hypothetical tool that could be accessed as needed by a client:It has to be short, modular and practical…You have to be able to bounce around. You don’t do module one, module two, module three. If I’m interested in “how do I bring up a sensitive topic”, I’m going to skip module one to six and go right to number seven.

When asked to describe what they would like to get out of an online tool, most participants spoke of prevention and interactive learning techniques. There was interest in tools that would help change behaviours, promote respectful interactions and prevent individuals from inadvertently causing an issue to escalate. Participants also complained that the online training currently provided to them was insufficiently interactive, amounting to no more than clicking through presentation slides. Interest was expressed in a tool that was interactive and engaging to its users.

All nine participants expressed a level of interest in tools for the purposes of education and stated that they could see themselves or their offices using such a tool. One participant’s interest in an education-oriented tool focused largely on the possibility of simulated mediations for training and hiring purposes. Two others reported that they were curious about the potential of an education MODR tool but did not discuss it at significant length. The remaining six participants actively engaged in discussion, generating ideas about what would be useful in their offices. The findings presented in this section reflect all responses. -

4 Discussion and Analysis

4.1 Receptivity to MODR Tools

Participant receptivity to MODR tools was perhaps the most crucial question of this study. Understanding participant receptivity to MODR tools requires knowing whether they are open to ODR options or not. What aspects of an MODR tool would participants welcome? To which would they be opposed? In what circumstances would an MODR tool be welcomed? In general terms, all participants were receptive to introducing an MODR tool to the dispute intervention services they currently receive or have received.

During the interviews, discussions between participants and the researcher generated an assortment of different ideas about what a useful MODR tool might look like. Participants were asked if and how they could see themselves and their offices using ODR or MODR tools. Differences among participant responses were the result of the varying tasks, job expectations, office environments or cultures in which the participants worked and their own individual perspectives.

Every participant was also strongly protective of the current services they received from their current service provider and were receptive of MODR tools only insofar as they would not replace or limit any in-person interventions and training seminars. Even when participants had received the majority of their services in the form of telephone conversations, they did not wish to see those services reduced. Any tool welcomed by clients would therefore have to be supplementary or additional to the established services.

Participant encounters with ODR systems were mixed, with some individuals reporting highly successful experiences, while others shared stories where ODR or CMC was a major contributing factor to disputes. None of the negative experiences with ODR resulted in reluctance among the participants to work with some form of ODR/MODR tool, but for some it did result in an unwillingness to use ODR for active disputes. Challenges with Internet technologies, particularly related to hardware and connection standards, made the weaknesses of CMC outweigh the benefits of ODR.

Participants held mixed attitudes towards online communication, which is in line with the findings of the literature review, as presented earlier. The literature review found that online communication is considered deficient in terms of conveying the social and contextual cues of conversation. All participants addressed weaknesses inherent to online communication, including missing cues or misconstrued phrasings. Online communication of some form was necessary to the work of all participants, and they were therefore very interested in any type of tool that could aid in limiting misunderstandings. Participants primarily used online platforms to disseminate information when communicating with the public. Two participants reported that their office monitored online discussions to understand the concerns and interests of the groups with whom they engaged with in the course of their work. However, there was minimal evidence of active interactions between users of online platforms, such as social media, official websites and the participants’ offices. This limited use of online communication capabilities reflects the academic literature in that ODR processes are underutilizing many forms of CMC.

Considering the experiences and needs of the participants, the most practical application of an MODR tool would be as a preventative measure. Misunderstandings in online communication and disruptions to dispute resolution processes caused by technological glitches were significant concerns among the participants. The multitude of features a tool would require in order to address the needs of all or most participants in active disputes or conflicts in differing work circumstances would be unsustainable. However, all participants were receptive to education-oriented and preventative tools, whose design could incorporate versatility and generality more easily than could tools for active disputes.4.2 Trust and Relationships

Data collected during the interviews demonstrates differing perspectives on how online communication impacts the development of relationships. These dissimilarities are largely attributable to differences in workplace culture. In smaller, single-location offices, relationships between colleagues were developed and maintained in person. This makes sense as communicating online without in-person communications alongside would generally be unnecessary. Alternatively, in offices where employees were dispatched to various rotating locations or in which work often required communicating with other, geographically distant offices, CMC was a standard medium through which trust and relationships were developed. Participants were asked to share their perspective and experience on the matter regardless of which of these two categories their office fit, as one of the purposes of this project was to examine the impact of CMC on relationship aspects of dispute resolution.

Trust seemed to be highly dependent on three factors. First, the quality of any pre-existing relationship between the individuals influenced trust in online interactions. If there was a pre-existing relationship that had deteriorated to the point that resolving a dispute required intervention, then the participants reported trust as something that was difficult to effectively establish, or re-establish, online. Of course, in the described scenario, trust would also have been difficult to establish between the individuals in in-person interactions. Any technological difficulties that would impede the ODR process would limit its effectiveness and risk further erosion of trust.

Second, participants who reported that they had established trust through CMC had more experience in communicating online. When the work environment placed expectations on employees to conduct business through CMC and the people with whom they were communicating were similarly accustomed to using CMC, then trust was more easily established.

This speaks to an expectation bias – when individuals on both ends of communications are expected to establish trust online, it is easier. When online communications are outside of the normal process for employees, it is harder. This difficulty is understandable particularly in the cases provided by participants, in which Internet technologies were introduced to instances of dispute. When participants reported successful trust-building processes they were often, but not always, using CMC for dispute- and non-dispute-related communications. Those reporting difficulties were less likely to discuss extensive CMC use in non-dispute scenarios.

The attitude disputants displayed was the third commonly reported factor influencing trust building and was related specifically to building trust during online dispute resolution processes. Participants who had experience in hosting virtual mediations recounted that in their experience, cases of CMC-assisted mediations with difficult personalities or attitudes were significantly less successful than in-person mediations. They found it harder, as the person working in a conflict resolution role, to control the conversation when the parties and/or they themselves were present only on a screen.

In most discussions of relationship development through online communication, participants stated that they had a previously established relationship with the other individual. Relationships were established in person and used CMC to maintain the relationship afterwards. Impacts of online communication fell into three categories: neutral, negative and positive. As noted in the findings, participants who claimed CMC usage had no influence on trust and relationships discussed relationships that were well established prior to CMC use. This neutrality was something new to the research, as the academic literature reviewed focused primarily on online customers and communities that could not include in-person relationships. The impacts of CMC on relationships that routinely exist both in person and online is something that requires further study.

Negative impacts manifested most prevalently in active disputes. In situations where a dispute had already reached the level of a third-party intervention, CMC negatively impacted both relationship and trust development. There was a significant overlap between participants who had experienced these negative impacts and those who cited specific instances in which an ODR process had become challenging because of technological difficulties with the system. Negative impacts due to technological difficulties are simple in theory to counteract. Simplified systems that can operate on a variety of different devices would be necessary. Negative impacts also presented in instances where the meaning of messages sent online was misconstrued. Owing to the lack of social, facial or tonal cues, written messages of any sort will always carry added risks of misunderstandings. Some participants reported methods they used to offset this risk, such as indicating tone through careful wording or emojis, and taking at least a day between reading an emotional email and sending their response.

Positive impacts were reported in situations where online communication was intentionally applied to develop relationships. Actively embracing CMC was a major factor in creating positive impacts for the participants. When miscommunications occurred online, participants reported responding in the same format to provide corrected information. Multiple participants shared practices of reaching out to their colleagues, either entirely online or in person and subsequently online to further solidify a relationship. Just as attitudinal factors influenced trust building, the attitudes and office practices towards online communication significantly influenced how it impacted relationship development. It is fair to assume that all users of online communication will have good and bad experiences. By noting what worked and what did not work, some participants were able to nurture relationships through the use of CMC. When communicating with someone over longer periods, participants reported developing similar trusting relationships to those developed in person.

The importance of trust in the development and maintenance of ongoing relationships was discussed in the literature review. It is possible to develop both cognitive and affective trust online. Two study participants spoke of online activity that their office had undertaken to improve the relationship between themselves and the public. By embracing CMC usage and intentionally humanizing the online communication process, they were able to establish a more trusting relationship with vocal and often argumentative online communities that represented segments of the public they dealt with in their work. Through ongoing engagement with these groups, a history of communication was developed and cognitive trust was established. As a result of personalizing interactions as much as was reasonable, the online community recognized that they were interacting with an individual rather than an abstract government office. This established a more emotional connection and supported the development of affective trust.4.3 Supplementing Services with MODR Tools

The primary research question addressed by this article looked at how MODR tools could enhance the dispute intervention services currently provided by dispute resolution and prevention trainers. As stated previously, participants were receptive to MODR tools that would supplement or expand on in-person training. Participants talked about virtual mediation technology, tools to guide public conversations on social media, videoconferencing tools to bring subject experts into mediations, education and dispute prevention. Out of all of these, education and dispute prevention applications were the only uses of an MODR tool that all participants stated they and their offices would find beneficial.

Participants who spoke directly about the training they had received from the dispute resolution and prevention service provider were positive about their experiences. While the knowledge and skills taught by the company were well received, interviews highlighted a space in the current services for an MODR education tool. The issue reported by participants was the limited extent that the information provided in seminars was being retained and applied in the daily working environment in the weeks and months following training. This demonstrates that participants see the interventions currently provided as highly beneficial but would appreciate a way for seminar attendees to improve their ability to retain knowledge and apply skills long term. Participant descriptions of a potential education tool indicate it would be most useful as a resource available to their offices after, not before, other training provided in person.

Data collected during interviews showed that misunderstandings that occurred through the course of online communications were both a major concern for participants and a cause of dispute escalation. The examples provided by participants demonstrate insufficient levels of trust between individuals in communication. Without sufficient interpersonal trust, disputants can more easily interpret text-based messages with tones or inflections that, as the reader, they assume the sender intended to convey. Promoting awareness of this issue and making advice about good and bad online communication techniques readily available to clients would help prevent disputes and dispute escalation. Dispute prevention in this area can also be linked to trust development. Strengthening cognitive and affective trust – and consequently strengthening the relationship between individuals – has the potential to limit misunderstandings. When disputants can trust each other, they will be less likely to negatively interpret written statements.

Evidence from the literature review suggested that data security would be a primary concern for any user of an online dispute resolution tool. Among the nine participants of this study, only two individuals mentioned security as a concern or necessity for a potential ODR/MODR tool. This notable difference between findings from this study and from past research could be attributable to a number of factors. Participants primarily hypothesized an MODR tool to be generic in nature, designed to supplement education services. As such a tool would require little, if any, personal data, security of information would not necessarily concern participants. Another possibility is that participants had already established a trusting relationship with the dispute resolution and prevention service provider through their previous interactions and that that trust created an assumption among participants that any tool provided – and accepted for use by their government employers – will have sufficient security measures. As the researcher did not specifically ask participants about potential security concerns, this subject remains largely conjectural. However, when asked to describe what they would need a potential MODR tool to provide, only the two aforementioned participants discussed security.4.4 Summary

The analysis of CMC usage on trust and relationships found that the impact of CMC on these two features of the dispute resolution process was highly dependent on previously established personal relationships and on workplace cultures. If participants’ offices routinely engaged in some form of ODR, then the use of online communication platforms had minimal impact on the dispute resolution process. However, if a personal relationship had been significantly damaged, any technical issues with connections or devices often lessened the effectiveness of the resolution process.