Culture-Sensitive Mediation: A Hybrid Model for the Israeli Bukharian Community

-

1 Theoretical Background of Mediation Models

1.1 Western Mediation Models

The literature and the practice of mediation offer a wide variety of models of how to conduct a mediation process. In Israel, most of the models taught and practiced are based on the Harvard interests-based mediation (Fisher and Ury, 1981). This model is based upon four core principles:

Separate the people from the problem: The problem at the core of the dispute is owned by none of the parties and should be addressed without assigning fault to any of them. The idea is not necessarily to find a joint and objective point of view, but rather to expose the subjective viewpoint of each party as a means to explore solutions that can satisfy both parties simultaneously.

Focus on interests, not positions: Usually the disputants form their ‘positions’ – they make decisions and then entrench themselves into them. The interests are hidden behind the positions. These are rather latent motives, needs, concerns and wishes that pushed each party to form their positions. It is very difficult to find solutions between contradicting positions, but in an interest-based negotiation, it is possible to ‘trade’ interests and even to discover joint interests.

Win–win solutions: the aim is to reach an agreement in which both parties feel that they gained more than any alternative can offer them. These are achieved by abandoning the ‘zero sum game’ perception of the dispute, adding issues that can be traded, compensating for something that was not included in the basic demands, etc.

Insist on objective criteria for decisions: Rely on standards, price lists, precedents and laws and regulations. These will enable solutions that are perceived as ‘fair’.

In mediation training courses, participants acquire theoretical knowledge and a set of competencies known as the mediator’s toolbox (Appendix 1).

The Harvard-inspired theory of mediation, rooted in negotiation theory, was harnessed into practical stage-by-stage mediation models. Among these are Kovach’s (2005) 13-stage model and a 7-stage model developed by Israel’s Ministry of Justice (Lee-On, 2000). Kovach takes the disputants through the following stages:

(1) Preliminary arrangements, (2) Mediator’s introduction, (3) Opening remarks/Statements by parties, (4) Venting (optional), (5) Information gathering, (6) Issue and interest identification, (7) Agenda setting (optional), (8) Caucus (optional), (9) Option generation, (10) Reality testing (optional), (11) Bargaining and negotiation, (12) Agreement, (13) Closure.

The procedure set forth by the Israeli Ministry of Justice has seven stages (Lee-On, 2000): (1) Preliminary stage, (2) Introduction, (3) Problem description, (4) Finding interests and needs, (5) Possible solutions, (6) Agreement and (7) Conclusion.

Another model, also Western in orientation, is a six-stage model developed by Shimoni and Ezraty (2012) and is taught in basic mediation training courses. This model is used here for its simplicity, and our recommendations are based upon it. The six stages are:Intake: Gathering initial information about the dispute and the parties, preliminary assessment and decisions as to whether the case is suitable for mediation, the type of mediators required and the mediation strategy. Simultaneously, the disputants are approached, and their consent to participate is requested.

Framework formation: The first meeting between disputants and mediators. The mediators present the ‘opening declaration’, outlining the principles and methods that will be implemented in the mediation. The disputants are asked to acknowledge their understanding and consent, and then all participants sign an agreement to commence mediation.

Opening statements (positions): Both parties are present with the mediators; each one has the opportunity to tell the story from his point of view.

Emergence of interests: The mediators assist each party in understanding their own interests, mainly by asking open-ended questions and rephrasing the answers. Very often this is done in caucuses. Other elements such as relationships and alternatives (BATNA and WATNA3xBATNA (Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement) and WATNA (Worst Alternative to Negotiated Agreement) are key terms in the assessment of alternatives, described in Fisher et al. (1991).) are also explored.

Options generation: The mediators facilitate the generation of creative options that serve the disputants’ interests. Usually the mediators will reframe the conflict and define the issues to be addressed, and then options are generated, preferably by the disputants, and evaluated.

Agreement: The agreed-upon options are assessed, organized and discussed until a final agreement crystallizes. All parties and mediators sign the written agreement.

Despite the difference in breakdown and number of stages, all mediation of the above mediation models belongs to the pragmatic school of Fisher and Ury, described above, and have one aim – helping disputants reach a point of understanding where they can see each other’s perspective and move on to resolve the conflict. All models offer a structured path that leads from ‘positions’ to ‘interests’ and to an understanding that agreement can be reached only if both parties are satisfied with the results. They all rely on the mediators’ toolbox (Appendix 1).

1.2 Mediation in Special Cultural Groups

Standard (Western) mediation, culture-sensitive mediation and mediation by trained indigenous conflict resolvers are the three basic models for mediation in special cultural groups.

Standard mediation is based on the assumption that conflicts have universal characteristics. The idea of standard mediation has produced a variety of mediation models, such as interest-based mediation (Fisher, Ury, & Patton, 1991), transformative mediation (Bush and Folger, 1994; 2005) and narrative mediation (Winslade and Monk, 2000), all complemented by practical models and techniques.

Culture-sensitive mediation reflects the notion that conflicts can be described by general theories and engaged by trained mediators, and that when mediating in different cultures, some adjustments in the process and conduct of the mediators are required. An excellent example is the extensive work done in Singapore to adjust interest-based mediation to the Asian context (Lee and Teh, 2009).

Within the third model, mediation by trained indigenous conflict resolvers was initiated by peacemakers who engaged in conflicts between ethnic groups or within traditional cultures, and began training indigenous conflict resolvers, teaching them mediation thought and technic. Lederach (1996; 2003), working in Central America, understood that local indigenous leaders and other conflict resolvers will be more suitable to engage in conflict resolution within their communities than ‘outsiders’. Lederach then advocated an ‘elicitive’ model, by which indigenous conflict resolvers contribute to their training by adding their specific cultural context and setting to the emerging mediation model.

The present study describes the process that led to the construction of an innovative hybrid model, after an attempt to introduce indigenous conflict resolvers into the Bukharian population of Ramla turned out to be inappropriate. The Bukharian community and culture will be described with a view to providing the background for the need in a new mediation model. -

2 Research Context: The Bukharian Immigration and Adjustment to Israel

Bukharians are good storytellers, and many biographies and descriptions of the life and history of the Bukharian Jews can be found. However, few recounts are well researched and documented. Pozailov (1995; 2008) has written about the Bukharian community, its origins and way of life. According to Pozailov, the first Jewish immigrants from Bukhara came to Mandatory Palestine in 1870-1920, following the Russian occupation of parts of Uzbekistan in 1868. This first wave, mostly prosperous families, settled in Jerusalem and established what is known today as the Bukharian Neighborhood (Pozailov, 2008). The second wave brought Bukharian Jews to Israel in the 1970s, when the Soviet Union allowed Jews to leave the USSR. Some 10,000 Jews came to Israel, seeking a better life and religious freedom. Following the collapse of the USSR, about a million Jews immigrated to Israel between 1989 and 2000, among whom were about 125,000 Bukharians (Pozailov, 2008).

Israeli MP Amnon Cohen, himself of Bukharian origin, describes the community as traditional, consisting of clans and exhibiting tribal characteristics such as living in Bukharian neighborhoods, and conforming to the close community. The families are patriarchal, with the father as the top authority, seconded by the mother-in-law (the father’s mother). Many women are not employed, and the older generation is not fluent in Hebrew and speaks Bukharian or ‘Jewish Tadjik’ (Cohen, 2012).

Donitsa-Schmidt and Molkondov-Dahan (2007) researched the acculturation of the Bukharian community in Israel, and found differences between them and most other groups who came from the USSR. Unlike the other communities, the Bukharians maintained their ethnic identity. They avoided marriage outside of their community and maintained close family ties and close relationships within the community. Many Bukhara-born Jews in Israel adhere to the traditional- religious lifestyle, and many Bukharian families are large. Looking at the older and younger generations, these researchers found that both generations espouse the integrative pattern of adaptation – combining adaptation to the new culture and language while maintaining their linguistic and cultural heritage. However, maintaining the traditional ways of life was more important to the older generation. Parents emphasize family and inner community ties, while the younger generation expects external agents to help preserve the culture and language. In both cases, the desire to preserve the Bukharian culture and language is not at the expense of the Israeli culture and the Hebrew language, with folklore and cuisine being most important to preserve. Such an acculturation pattern is known as an “assimilation in disguise” (Donitsa-Schmidt and Molkondov-Dahan, 2007: 9): giving the illusion of integration, while preserving folkloric and symbolic aspects of the original culture. -

3 Purpose of Research and Main Research Questions

This study describes the research that was conducted in order to gain an in-depth understanding of the values and dynamics of a defined cultural-ethnic group and use this knowledge to find patterns of mediation that are appropriate for this setting. The group is the Jewish Bukharian community in Ramla. The investigation included questioning the compatibility of the Western mediation model with its values, traditions, social institutions and other cultural characteristics, and suggesting a specific conflict resolution model suitable for the community. Furthermore, our aim is to create a generic method of tailoring a conflict resolution model to any traditional community.

Specifically, the research addresses two research questions:How do the Bukharians in Ramla define their cultural characteristics?

What are their preferences when they elect to refer their conflicts to a third party?

-

4 Method

This mixed-method study, conducted during 2010-2012, was designed to answer the above research questions (Shimoni, 2012). The quantitative tools included structured questionnaires and the qualitative methods – open interviews and focus group sessions.

4.1 Methodological Foundations

The underlying assumption of this study is that conflict resolution is sensitive to its cultural, social and historical settings. Hofstede’s (2001; 2008; Hofstede and Hofstede, 2005) works and methodology were adopted in this study to investigate and define the specific characteristics of the culture of the Bukharian community in Israel. Four dimensions will be examined: (1) PDI = Power Distance Index, (2) IND = Individualism versus Collectivism, (3) MAS = Masculine versus Feminine culture, (4) UAI = Uncertainty Avoidance Index.

1. Power Distance Index. This dimension describes “the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally” (Hofstede and Hofstede, 2005: 46), or how acceptable it is that some people have privileges and others do not. Hofstede demonstrates this dimension by comparing cultures with high PDI scores and those with lower scores.

2. Individualism versus collectivism. This dimension refers to the affiliation that people have to groups in various cultures. A high score of individualism appears in societies in which the relationships between people are loose and one cares mainly for his nucleus family. Hofstede found that the minority of cultures are individualistic and that they are concentrated in the West. High scores on the Collectivism Index appear when the individual is born into strong and cohesive groups, extended families that protect their members and demand total loyalty. Hofstede’s studies show that collectivism is high in second- and third-world societies.

3. Masculine versus feminine culture. The masculine culture is goal oriented, strives to achieve excellence and is ambitious, while feminine culture seeks life quality, relationships, modesty, mutual help and compassion.

4. Uncertainty Avoidance Index. Hofstede uses this dimension to describe tolerance to ambiguous situations and the degree to which a culture ‘programmes’ its members to feel uneasy in uncertain situations. Cultures that do not tolerate uncertainty adhere to strict rules and regulations, differentiate between truth and lies and accept only one opinion as right. Germany is an example of a culture that does not tolerate uncertainty, whereas in Singapore people can live with ambiguous situations. Groups that can live with uncertainty can also live with conflicts, avoid confrontation and arguments and not seek decisive rulings. Groups that avoid uncertainty will favor direct confrontation and will seek a final clear decision. They require precise details and unequivocal answers.4.2 Research Population

In the quantitative part of the study, 82 members of the Bukharian community filled in structured questionnaires. For the qualitative part, 15 Bukharian volunteer mediators participated in focus group discussions, and 3 community leaders were interviewed (one wealthy businesswoman and two rabbis).

4.3 Research Tools

Three-part questionnaire – demographic information, preferences of intervention in conflicts and cultural dimensions, based on Hofstede (2005; 2008). Using Hofstede’s tools enables a cross-cultural comparison of our findings with those in other cultures and further establishes the soundness of our model.

Focus group and interviews – these were conducted by the author of this article (Shimoni, 2012) using Hofstede’s terminology and dealt with participants’ preferences for conflict engagement methods and goals.

Below is an elaboration of the questionnaire part of the research.

4.4 Research Procedure

Twelve certified mediators, all members of the Bukharian community, distributed questionnaires to community members. These volunteers were active in the design, construction and execution of the study. They assisted in constructing the questionnaires and translating it into Russian from Hebrew. Prior to distributing the questionnaire, they received training in approaching participants, explaining the purpose of the study and helping them with the questionnaires. The volunteers were taught the ethical aspects of the research and the way to fill the questionnaire. Each volunteer approached 10-12 community members, thus achieving a cluster sample.

4.5 Sample

The volunteers distributed 180 questionnaires, of which 82 were returned filled in (63 in Hebrew, 19 in Russian). Participants (50 men, 32 women) ranged in age from 20-72, with the largest group (23.3%) in the 40-49 years-old range. About one-quarter of the participants (25.8%) had fewer than 12 years of education, 40.9% had 12 (i.e. through high school) and 33.3% more than 12 years. Most participants (60%) were married. When asked about level of religiosity, 6.8% defined themselves as ultra-orthodox, 12.3% as orthodox, 17.8% as traditional-religious, 39.7% as traditional-not religious and 23.3% as secular.

The completed questionnaires were statistically processed with SPSS software, while the transcripts of the focus group discussion were analysed qualitatively in accordance with the Grounded Theory method (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). -

5 Findings

As for the questionnaires, participants were asked to list their preferred person/professional for handling conflict resolution (they could choose more than one). The preliminary evidence gathered in the sample suggests that they preferred traditional figures (43% would turn to a rabbi, 30% to an elder and 29% to a wealthy community member) to more contemporary/civic ones (28% would turn to a mediator, 13% to the courts, 5% to a Bukharian MP and 1% to the police).

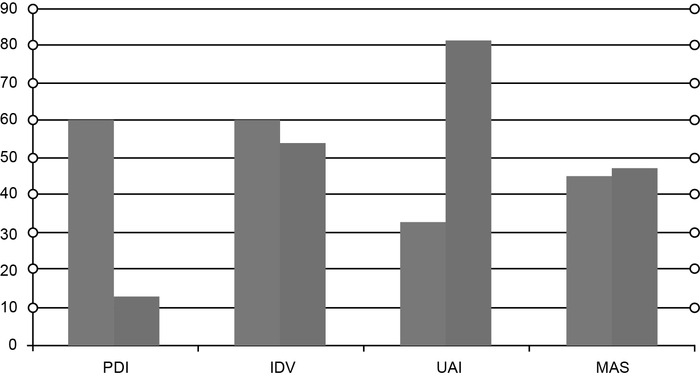

When the choice pertained to people within the community or outside of it, gender and social status, 31.5% preferred a Bukharian person, 11.1% a non-Bukharian and over half (57.4%) had no preference. More participants (28.2%) prefer a man to a woman (20.5%), and over half (57.4%) had no preference. More participants would choose an important person (43.5%) or a community elder (64.1%) rather than their social equal (21.6%) or a young person (2.6%), with 30.4% showing no preference in the choice between important person and equal, and 33.3% showing no preference for an elder or a young person. Finally, 41.7% would turn to a lawyer, 2.8% would not and 55.6% showed no preference. However, there are distinct differences between the preferences of younger and older people, and these are listed in Table 1. Most significantly, elders favor a wealthy Bukharian as a suitable conflict resolver, while the youngsters do not, and some youngsters will take their disputes to a Bukharian parliamentarian (M.P.), but no elder will do so.Table 1:Preference for person to resolve conflict by age of participantsParticipants were asked to characterize their society. The answers were applied to Hofstede’s ‘cultural dimensions’, and compared with the characteristics of general Israeli society as perceived by Hofstede (Figure 1; see also Hofstede, 2001, <http://geert-hofstede.com/israel.html>).Preferred person to resolve conflict All participants (N = 82) (%) Younger (under 40) N = 32 (%) Older (over 40) N = 50 (%) Difference Rabbi 43 46 40 Old and respected person 30 26 33 Wealthy Bukharian 29 9 36 Significant Mediator 28 44 21 The Court 13 23 7 Bukharian M.P. (Knesset) 5 10 0 Significant The police 1 5 1

Two dimensions – power distance index and individualism – were rated highest (a score of 60), indicating a rather stratified society where hierarchy is accepted as natural and individualistic values are socially accepted. Next was the masculine/feminine dimension, where it was found that relationships are more important than achievements. The lowest score (32) was for uncertainty avoidance, revealing the hallmarks of a culture that can feel comfortable with ambiguity.Bukharian (in light grey) and Israeli (in dark grey) responses to cultural dimension questions (Bukharian scores from the research questionnaires, Israeli scores from Hofstede, 2008).

In addition to the questionnaires, we had a focus group whose members were first asked to discuss Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and their presence in their everyday life:

Power distance: The focus group members reported that there is power distance in the Bukharian community and that such distance is accepted. They mentioned that some people are of dignified families and that others – wealthy people or those in important positions – can also belong to this social elite. Some members of the focus group stated that men are of higher status than women.

Individualism versus collectivism: According to most members of the focus group, Bukharians attribute more importance to the individual and the immediate family than to the whole group. Nevertheless, they see the family as superior to the individual member.

Masculine versus feminine culture: The group was evenly divided between those who said that performance is more important than relationships, and those who held the opposite view.

Uncertainty avoidance: Most members of the focus group believed that Bukharians can live with ambiguity and disagreement and may prefer to remain in disagreement and not to create tension. This way, harmony and peace of mind are maintained. As part of the desire not to create tension, members of the group all said that Bukharians do not express their feelings and maintain a ‘poker face’ when angry, another way of smoothing rough edges and of maintaining ambiguity.

Next, the focus group discussed the perception of the Bukharian preferences regarding intervention in conflicts.

Bukharian or non-Bukharian dispute resolver: Opinions varied, with those who prefer a non-Bukharian doing so for fear of gossip. They agreed that elder Bukharians would prefer a Bukharian mediator, while the youngsters would prefer someone external.

Characteristics of preferred mediator: Almost all members of the focus group said that Bukharians prefer a ‘dignified’ person – rabbi, wealthy person, member of the Knesset or a person in a senior position. Women are definitely accepted as conflict resolvers.

Direct or indirect speech: All members of the focus group recommended separating disputants and caucusing with them in different sessions. Only after careful caucusing would they be ready to have joint meetings.

Responsibility for settling dispute: Most members of the focus group were certain that Bukharians would prefer to decide about the outcome of a dispute settlement process and not to receive a dictated result.

Honor: Group discussions revealed that honor held a central position in Bukharian society and that the group was committed to strict codes of honor. The Bukharians are very sensitive about their social image, although mostly in the context of their families and the community and less within the larger Israeli society. For example, a Bukharian man will accept a lower position at work and the lack of manners at the workplace, but will demand respect from his wife and children.

Conflict situations perceived as threatening one’s honor: Loss of face, gossip, loss of authority, questioned manhood and a sense of helplessness.

Interviews: Three Bukharian dignitaries were interviewed a number of times during the study, and they provided background information about the community and its characteristics. Their insights correspond with those of the focus group. -

6 Discussion

This study aimed at answering two questions, in order to build based on the findings a mediation model: First, how do the Bukharians in Ramla define their cultural characteristics? And what are their preferences when they elect to refer their conflicts to a third party? Here are the answers to these questions.

6.1 Bukharian Cultural Characteristics

Analysis of the questionnaires shows significant differences between Israeli and Bukharian respondents in two of Hofstede’s dimensions: PDI (Power Distance) and UAI (Uncertainty Avoidance). Bukharians accept hierarchy and inequality as normal, while Israelis do not accept power distance and are graded with a very low score on the PDI dimension. The Bukharians are at ease in uncertain situations, while Israelis do all they can to avoid uncertainty. The focus group discussions confirm these findings.

Other dimensions examined in the study indicate that Bukharians, like most Israelis, see the individual as central and capable of deciding for himself.

With regard to other cultural dimensions, both the questionnaires and the focus group indicate the importance of the individual over that of the large group, although the nucleus family is seen as the basic affiliation unit.6.2 Preferred Third Party Conflict Engagement Methods

The mediator: Responses to the questionnaires and the focus group discussions indicated a clear preference for community dignitaries such as rabbis, respected elders, wealthy Bukharians or Bukharian senior politicians, rather than ‘outsiders’ – the courts, modern mediators and the police. When asked about choosing a mediator, more than half of the participants showed no preference for a Bukharian mediator. The younger participants showed a lower preference for community solutions than for modern mechanisms. Interestingly, gender is not a factor when selecting a third party to assist in conflict resolution, yet, overall, the preferred figure to serve as mediator is an elderly and socially respected person.

The mediation process. The questionnaire findings suggest that the Bukharians favor a conflict engagement process that follows Western mediation patterns such as expressing one’s feelings, seeking a good solution and assuming responsibility to solve the dispute. However, the focus group recommended a series of caucuses before the disputants are ready for a joint session, especially when the parties are of different social status. Thus, if an elderly man is asked to meet in a joint session with a younger person in an attempt to create an atmosphere of equality, he may perceive this invitation as an offence. The inconsistency between the questionnaire and the focus group is explained by social desirability – the participants wanted to please the volunteer mediators who interviewed them.

The interviewees showed a tendency to adhere to their original culture by preferring mediators who are respected figures in their community. However, they also favored Western characteristics of a conflict engagement procedure of open discussion and of reaching an agreed, rather than a dictated, solution. This preference is compatible with the Donitsa-Schmidt and Molkondov-Dahan’s (2007) description that the Bukharians adjust to Israeli culture following the integration model, which means they strive to conserve their original culture while adopting elements of the target culture.6.3 Designing a Community-Specific Mediation Model

On the basis of the above findings, it was possible to construct the specific mediation model for the Bukharian Jews. While some Bukharian cultural characteristics are incompatible with Western mediation, a culturally adjusted mediation model comes in handy because this community tends to solve their disputes internally, preferably by agreement. Noting this preference, it seemed reasonable to introduce mediation as a way to engage conflicts within the group, with adjustment to accommodate the unique cultural attributes.

6.3.1 Selection of Mediators

The findings indicated that the mediator should be a mature person, of high social status and that the rabbi was the preferred figure among the distinguished community members. Existing community mediation centers have wisely selected co-mediation as their modus operandi, and this approach allows a hybrid model that looks specifically suitable for the Bukharians:

Two mediators: one is an authoritative figure, and the second is a professional mediator

Both mediators should be mature

Woman can serve as mediators

Both mediators need not be Bukharian

The idea of hybrid mediation was born of these findings and discussions with the volunteer Bukharian mediators, using a qualified ‘Western’ mediator and a traditional conflict resolver. Community mediation centers in Israel advocate and practice co-mediation in most of their engagements. It was therefore suggested that if a traditional figure could collaborate with a trained mediator, the disputants and the process would enjoy the benefits of both. The traditional conflict resolver would contribute his or her knowledge of the culture, personal ethos and encouragement to maintain the cohesiveness of the community by mitigating conflicts. The ‘Western’ mediator would provide a framework for the process, the mediators’ toolbox and – more important – striving to reach an agreed solution based on the interests of both parties.

6.3.2 Mediation Process

Mediation literature and practice present a variety of mediation models. Most of the models practiced in Israel are based on the Western Harvard model – interest-based mediation and facilitative mediation. The hybrid model developed below is based on a six-stage Western-oriented model that was developed, as mentioned above, by Shimoni and Ezraty (2012). This Western-oriented model is used in this article because it is simple and easy to learn, taught in basic mediation training courses and is adaptable to special populations. Following are the details of the Western-oriented model and the modifications introduced in it for working with the Bukharian community:

1. Intake. This is the pre-mediation stage in which the mediators become familiar with the dispute and design their strategy. Simultaneously, they seek the consent of the disputants to take part in mediation.

When engaging a dispute within the Bukharian community, the boundaries between intake and mediation can become blurred. The Bukharians favor caucusing, which means that the mediation actually develops during intake. Intake can include a series of caucuses with each one of the parties in which the terms for participation, the issues to be addressed and the setting of the joint sessions are discussed. It is therefore recommended that the consent of all parties be sought to participate in the process even though the first meetings are separate. All parties should be informed that the mediators are working with the other parties.

When explaining the principles of mediation, it could be useful to use traditional Bukharian sayings that demonstrate mediation principles (e.g. “We will work in a way that neither the meat nor the skewer will be burned”4xI am grateful to Yael Mehl, who so generously shared her knowledge of Bukharian proverbs.). Mediation could also be presented as an honor-building process.

2. Formation of framework. In Western mediation, this is accomplished in a joint meeting in which the mediators present the concept and rules of mediation and seek the consent of the disputants to continue.

As mentioned above, when engaging a conflict within the Bukharian society, the framework may be set in separate meetings, in which case it is important that each party be presented with the full ‘mediator’s opening declaration’. Despite Western mediators’ use of informal speech and first names, the Bukharians could prefer formal titles and surnames, and this should be accepted by the mediators. A written and signed agreement to enter mediation may not be necessary, especially if one of the mediators is one of the community dignitaries.

3. Presentation of positions. The mediators may choose to conduct this important phase in caucuses rather than in the standard joint session. Presenting the positions can involve mutual attacks on the honor of the opponent and threaten the honor of the speaker. Caucuses allow ventilation, exposure of useful information, elaboration in the interpretations and feelings of each one of the disputants and good reflection work by the mediators. It should be noted that mediators do not seek facts and therefore need not confront the parties’ different versions of the story. What is important in mediation is the mutual exposure of interests, and this will happen in the later stages.

Bukharians do not express their feelings openly, and their presentation of positions tends to be laconic and monotonous. Active listening techniques are very useful at this stage. When reflecting the parties’ statements, it is important to include the facts presented as well as the interpretations and emotions, and the harm and threat to the disputants’ honor.

4. Emergence of interests. Alongside the actual issues of the conflict (damages, decisions about money and property, conduct of behavior, etc.), there are also ‘soft’ aspects of the disputes that the parties can try to dodge.

As the Bukharians tend to leave these issues vague and ambiguous so as to avoid escalation and disruption of harmony, the mediator should encourage them to elaborate so that their interests will emerge and become clear – to themselves and to others. For example, there may be a strong need to restore one’s honor, something that a good apology can achieve. Despite the fact that the disputants are practical and pragmatic people, recognizing ‘face’ issues and dealing with them could take precedence over the technical aspects of the dispute.

During the emergence of interests stage, additional “elements” (Patton, 2005) can be examined, such as communication, alternatives and options:

Communication: Bukharians prefer ambiguous and indirect communication, in complete contrast to Israeli style, which is blunt and direct. In mediation, the Bukharians maintain a quiet tone and express their messages in neutral terms and hints. This demands that the mediators be sensitive and competent, so they understand the undercurrents and encourage the parties to express themselves in a manner that will allow the real issues of the dispute to be addressed. Sometimes the Bukharians will favor honor over truth and will tell some small lies to avoid damaging the other party’s honor or to maintain their own.

For many Bukharians, eye contact does not signify trust and candor. It rather constitutes an invasion of privacy, a manifestation of suspicion and is also perceived as a disrespectful act when done between people of different social strata.

Alternatives: In the classical mediation model, alternatives are the solutions that are available to the disputants if they fail to reach a negotiated agreement. The Bukharians will not rush to present their complaints to the police or the courts, but would rather turn to a figure of authority and ask for a ruling. Mediators must bear in mind the research finding that Bukharians like to solve their problems by themselves and not get a dictated resolution; a ‘reality check’ about their chances in perceived alternatives should be conducted in caucus so as to maintain their honor.

5. Options. This is the stage in which the mediators assist the parties to generate options – ideas for agreed solutions. The options stage should be conducted in joint sessions, each beginning with a reframing statement by the mediators. The interests of both parties should be clarified and mutual interests amplified, and the focus should be on the future relationships and the opportunity to reach an agreement.

Bukharians are good merchants and have the skills needed to evaluate the options. But they are used to getting solutions from persons with authority and will find it difficult to initiate suggested options. Encouragement and empowerment by the mediators can prompt them to generate good options. Introducing all interests can produce replacing concrete compensation with gestures that restore honor.

6. Agreement. Not all mediations end up with an agreement.

For the Bukharians, an agreement can be perceived as too concrete and measurable, and some will hesitate to put it in writing. A dispute that did not end with a court decision could be concluded in a verbal agreement. ‘Sanction clauses’ (for failure to comply with the agreement) are not recommended, and the parties’ ‘word of honor’ should be stressed. Mediation agreements that are not returned to the court can be reinforced if both parties agree to ask a figure of authority (e.g. a rabbi) to endorse it.

All these recommendations point to a mediation model suitable for the Bukharian community, based on their cultural characteristics. The adjustments refer to the technique and procedure of the mediation. Nevertheless, the core principles of mediation, namely voluntary participation, interest-based negotiation, solutions that come from the disputants, an agreed solution, win–win and confidentiality, are maintained.6.4 Implementation of the Hybrid Model

Using this six-stage model has yielded positive results in working with the Jewish Bukharian population of Ramla in these two examples:

1. Marital dispute. A Bukharian couple. The husband had been under court-ordered house arrest after threatening to kill his wife. This mediation was performed by a professional mediator together with a prominent Bukharian rabbi. Two joint sessions and two caucuses led to a full agreement that covered the issues identified throughout the mediation: the wife’s employment and career, handling the family budget and finances, taking care of the children, the husband’s work on weekends and others. A clause in the agreement stated that the couple will jointly attend family-life lessons conducted by the Bukharian community. The agreement was signed by the couple and by the mediators and was concluded with a special blessing by the rabbi. The agreement sufficed to terminate the house arrest and to cancel criminal charges that were being formulated by the police prosecutors. The collaboration of a professional mediator with a distinguished rabbi, lengthy caucuses, the parties addressing the mediators as ‘the honorable rabbi’ and ‘Doctor’, the parties entering the mediation process without signing a written consent to mediation, the suggestions by the rabbi to attend lessons, extra sensitivity to ‘face’ issues, especially of the husband – all represent adaptations and deviations from the ‘normal’ Western model.

2. Dispute between families. All families were Bukharian, and the case involved an unfaithful young husband. The dispute involved the young couple, as well as the wife’s parents and a few uncles, and caused friction and bitter fights between the wife’s parents who were the main parties in the mediation. This case was co-mediated by a professional mediator together with an orthodox rabbi, not a Bukharian. Three sessions took place and were broken into joint sessions and caucuses. The relations were repaired and specific agreements were reached, but were not written. Bukharian honor and the rabbi’s authority were enough to ensure compliance with the agreement.

As in the previous example, here too deviations and adaptations allowed the mediation to proceed and succeed. Intake took a few weeks and involved a series of caucuses, long before the joint sessions took place; mediators and parties addressed each other with formal titles; joint sessions were rather short, and the mediators did not probe the disputants for information that could insult the other parties or the speaker; no written agreements were prepared or signed; Bukharian proverbs were used (‘a bird with a bird, a dove with a dove’).

These adaptations enabled reaching a resolution. The way to resolve conflicts requires not only the goodwill of the disputants, but also the mediators’ willingness to go beyond tried and true models and see the broader context. -

7 Conclusion

Traditional groups try to adhere to their customary conflict resolution mechanisms. The work and research performed with the sampled Bukharian community in Ramla provided an understanding of their particular characteristics and their preferences for third party engagement in their conflicts. The study has shown that Western models of mediation are incompatible with these characteristics and preferences. The findings suggested that Western mediation models, based on modern and postmodern values of democracy, equality and self-determination, require adjustments before being introduced into traditional settings.

The article reviewed various cultural sensitivity approaches regarding mediation training and practice and introduced a new concept: a hybrid model. This model calls for co-mediation performed by a traditional dignitary together with a professional ‘Western’ mediator. This allows conflict engagement that is voluntary and sensitive to interests, needs and also cultural preferences of the disputants.

The hybrid model was presented to a Bukharian focus group and to three prominent Bukharian leaders, and received their approval and blessing. It was then field tested and proved to be effective and beneficial.

It can be assumed that the ideas and practices presented in this article can be applied, with the necessary adjustments, in conflict engagement in many other traditional cultures and groups. References Bush, R.B. & Folger, J.P. (1994). The promise of mediation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bush, R.B. & Folger, J.P. (2005). The promise of mediation. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Cohen, A. (2012). MP Amnon Cohen’s Site. Retrieved 11 October 2012, from <www.amnoncohen.com/bokharan.php> (In Hebrew).

Donitsa-Schmidt, S. & Molkondov-Dahan, N. (2007). The language and cultural adaptation process of the Bukharian ethnic group in Israel. Hahinukh Usvivato (Education and Its Environment), 29, 183-195. (in Hebrew)

Fisher, R. & Ury, W. (1981). Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in. New York, NY: Penguin.

Fisher, R., Ury, W. & Patton, B. (1991). Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in. New York, NY: Penguin.

Fuller, L. (1971). Mediation – Its forms and functions. Southern California Law Review, 44, 305-339.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Hofstede, G. (2008, January). Values Survey Module 2008 Questionnaire: English language version (Release 08-01). Retrieved from <www.geerthofstede.nl>.

Hofstede, G. & Hofstede, G.J. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (Rev. and expanded 2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Irani, G. & Funk, N. (1998). Rituals of reconciliation: Arab-Islamic perspectives. Arab Studies Quarterly, 20(4), 53.

Kovach, K. (2005). Mediation. In M.L. Moffit & R.C. Bordone (Eds.), The handbook of dispute resolution. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Lederach, J.P. (1996). Preparing for peace: Conflict transformation across cultures. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Lederach, J.P. (2003). The little book of conflict transformation. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

Lee, J. & Teh, H.H. (Eds.). (2009). An Asian perspective on mediation. Singapore: Academy Press.

Lee-On, L. (2000). Community mediation theory and practice. Tel Aviv, Israel: Ministry of Justice, National Center for Mediation and Conflict Resolution. (In Hebrew)

Levin, L. & Wheeler, R.R. (1979). The Pound Conference: Perspectives on justice in the future. Proceedings of the National Conference on the Causes of Popular Dissatisfaction with the Administration of Justice. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing.

Menkel-Meadow, C. (2005). Roots and Inspirations: A brief history of the foundations of dispute resolution. In M.L. Moffit & R.C. Bordone (Eds.), The handbook of dispute resolution. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Patton, B. (2005). Negotiation. In M.L. Moffit & R.C. Bordone (Eds.), The handbook of dispute resolution (pp. 279-303). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Pely, D. (2008, November). Resolving clan-based disputes using the Sulha, the traditional dispute resolution process of the Middle East. Dispute Resolution Journal, 80-88.

Pozailov, G. (1995). From Bukhara to Jerusalem (Hebrew). Jerusalem, Israel: Misgav Yerushalayim.

Pozailov, G. (2008). Bukhara Jewry, leading figures, and customs (Hebrew). Jerusalem, Israel: Israeli Ministry of Education, Religious Education Administration and Unity of Bukharian Immigrants.

Shimoni, D. (2012). The adjustment of a conflict resolution model to an ethnic group – The case of mediation in the the Bukhari community in Ramla. Ramla, Israel: Ramla Community Mediation Center.

Shimoni, D. & Ezraty, Y. (2012). Basic mediation course manual. Ramat Efal, Israel: Goshrim Mediation Center.

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory – procedures and techniques. London: SAGE.

Tonnies, F. (1957). Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (C.P. Loomis, Trans. & Ed.). Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan State University Press. (Original work published 1887)

Winslade, J. & Monk, G. (2000). Narrative mediation: A new approach to conflict resolution. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Appendix 1 Active listening: Body language, eye contact, exhibiting interest, encouraging the disputant to elaborate

Repetition, summary, and reflection: Repeating the party’s narrative and outlining the main details of the way the party interpreted the events and the feelings and emotions expressed.

Rephrasing: Repeating what the party said in a manner that will be more acceptable to the other party and that expresses interests and not positions.

Open ended questions: Questions that allow and encourage free meaningful answers that will reveal interests, anxieties and information that can contribute to the mediation.

Venting: Allowing the parties to ‘let off steam’, to express their anger, frustration and fear legitimately. Venting enables the disputing parties to later address the issues in a more relaxed manner.

Empathy: The mediators show their understanding (but not their acceptance or justification) of the parties’ feelings. They also encourage some personal acquaintance as a means to empower the parties and thus create a platform of recognition and even generosity.

Conflicts are an inseparable part of our life, as evidenced from the earliest writings – the Hebrew Bible tells about individual, tribal and international conflicts. The Hindu Mahabharata is a long story of war between tribes and also between princes, and the Odyssey is only one example of the many conflicts recounted in Greek mythology. However, the history of conflict is also the history of conflict resolution mechanisms and performers, with a very popular method being the use of violent force, be it between feuding nations or tribes or between individuals. In an attempt to avoid violence, all societies have developed and maintained designated institutions, procedures and personnel to whom parties in conflict could turn in search of a more peaceful procedure.

Because conflicts are intrinsic to human nature and to social behavior, Menkel-Meadow (2005) coined the term conflict handling. This term pays homage to the attitude prevalent in many traditional societies that conflicts are natural and not necessarily in need of resolution.

Tonnies (1887/1957) offered a distinction between traditional communities (Gemeinschaft)1xGemeinschaft is the German word for community. Gesellschaft is the German word for organization or corporate. Tonnies described a Gemeinschaft as a traditional rural community in which relationships are emotional and based on kinship, while a Gesellschaft is a modern urban society in which relationships are rational and based on interests. and modern industrialized organizations (Gesellschaft). In the Gemeinschaft, social order was maintained through kinship-based relationships, and conflicts were resolved by distinguished members of society who used methods resembling arbitration and rituals that can still be found in traditional societies in the Middle East (Irani and Funk, 1998; Pely, 2008). These distinguished people had a dual concern – to maintain social order and their own status. Similar mechanisms were common in various Asian countries such as China, South Korea and Japan, where Confucian influence promoted social order and harmony (Lee and Teh, 2009) and respected members of the community handled disputes.

Modern social complexities and the evolvement of the Gesellschaft removed most traditional, community-based dispute resolution mechanisms and replaced them with legal, usually state-regulated ones (Lee and Teh, 2009). In this process, which progressed most widely in the U.S., laws and regulations were easily propagated and state nominated judges replaced the traditional peacemakers, ruling according to the written law. Litigation and arbitration became the common methods to deal with conflicts and are performed in institutions that are distant and secluded and in which disputants cannot talk to each other. The disputants in court talk to the judge, usually through lawyers who ‘translate’ their narratives into legal jargon.

Changing social awareness in the second half of the 20th century saw the rise of popular dissatisfaction with the American legal system and courts, as addressed by Frank Sander in his monumental speech delivered at the Pound Conference in 1976 (Levin and Wheeler, 1979). Sander suggested exploring alternative, out-of-court ways of resolving disputes, considering not only social trend but the workload of the courts. However, he added that introducing new dispute resolution mechanisms may encourage the ventilation of grievances that are suppressed by the rigid court system. Sander’s chart of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms is still taught today and is known as the ‘ADR Spectrum’: Adjudication – Arbitration – Mediation/Conciliation – Negotiation – Avoidance (Levin and Wheeler, 1979).

Following the Pound Conference, various disciplines joined forces to create a theoretical foundation and practical tools for the new mediation mechanism. The Harvard Law School together with the Harvard Business School created the Project on Negotiation (PON) that enabled the development of professional, interest-based mediation (<www.pon.harvard.edu/>). Mediation is usually defined as a dispute resolution method in which a mediator who is a neutral third party conducts a process of assisted negotiation and has no coercive power (Fuller, 1971). Israeli law defines mediation as “a procedure in which a mediator confers with disputants, in order to bring them to an agreement to settle the dispute, without [the mediator having] the authority to issue a ruling”.2xThe Courts Act, 1984, Section 79c.

Though Sander’s idea was to introduce mediation into the services that are provided by the courts (under the concept of the Multi Door Courthouse), mediation has drifted away from the courts, assuming a more informal approach. It enables ordinary people to resolve their disputes using ordinary language and making their own decisions, taking responsibility for the outcome of the negotiation. Mediation central quality, as stated by Fuller (1971: 351), is “its capacity to reorient the parties towards each other, not by imposing rules on them, but by helping them to achieve a new and shared perception of their relationship”.

The drift away from the courts gave rise to community mediation centers where the mediators are not necessarily lawyers. The return to old community values calls for the revival of traditional methods of conflict engagement, but these must be refined and adjusted so that they conform to the existing law and the individualistic approach of modern society.

This article will address the challenge of using Western mediation techniques and values in a traditional community and will suggest a hybrid model for mediation in such settings. The model was developed for working with the Jewish Bukharian community in Ramla, a town with mixed population, in central Israel. Although the outcome of this work is a mediation model that was constructed for a specific community in Israel, the method and tools that were used to reach the model can be replicated in any other cultural setting.

The present article will first describe the theoretical background of mediation models and its aim (constructing a model for the Bukharian Jewish community) and then go on to discuss the unique general characteristics of this community. It will then describe the methodology of the research that was used to explore the specific tendencies of this community that pertain to conflicts, then its findings and the hybrid model that was constructed on the basis of these findings. Lastly, the article will present the ways in which the model was successfully applied for mediation in disputes within the community.

The mediators’ toolbox:

Noten

-

1 Gemeinschaft is the German word for community. Gesellschaft is the German word for organization or corporate. Tonnies described a Gemeinschaft as a traditional rural community in which relationships are emotional and based on kinship, while a Gesellschaft is a modern urban society in which relationships are rational and based on interests.

-

2 The Courts Act, 1984, Section 79c.

-

3 BATNA (Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement) and WATNA (Worst Alternative to Negotiated Agreement) are key terms in the assessment of alternatives, described in Fisher et al. (1991).

-

4 I am grateful to Yael Mehl, who so generously shared her knowledge of Bukharian proverbs.