A Critical Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Grenada’s Legislative Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic

-

A Introduction

On 30 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared the outbreak of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, commonly referred to as the COVID-19 pandemic, to be a global health emergency.1x Available at: www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov). In response, a vast majority of states declared constitutional and statutory states of emergency or disaster to facilitate the use of emergency powers. Other states instead made use of ordinary legislative regimes, primarily pre-existing public health legislation, to regulate public attitudes and behaviours during the pandemic. Although not as common, some states adopted measures that incorporated the use of special legislative powers granted to the Executive under exceptional circumstances.2x Maria Crego and Silvia Kotanidis, ‘Emergency Measures in Response to the Coronavirus Crisis and Parliamentary Oversight in the EU Member States’, European Journal of Law Reform, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2020, p. 416.

Although the use of the foregoing normative measures was widespread, the approach taken by each state was unique, owing largely in part to the distinctive nature of each state’s existing constitutional and legal frameworks. This article focuses on how, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of Grenada has applied different legislative models to introduce both emergency and non-emergency measures.

This article will aim to prove that the non-emergency statutory measures were a more effective legislative response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Grenada insofar as their purpose, structure, content and results were better aligned and consistent, resulting in higher-quality legislation in comparison with the constitutional and statutory emergency measures which were also implemented during the pandemic. However, notwithstanding their comparative effectiveness, there is still room for the much-needed improvement of their overall legislative quality.

The primary objective of this article is to conduct an evidence-based assessment of how well Grenada’s COVID-19 legislation has performed the objectives it set out to achieve, identifying any changes that occurred, the extent to which these changes were influenced by the legislation or by other non-legislative factors and the primary actors affected by these changes. This article will test Mousmouti’s criteria of legislative quality, collectively characterized as the ‘effectiveness test’,3x Maria Mousmouti, ‘Operationalising Quality of Legislation through the Effectiveness Test’, Legisprudence, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2012, p. 201. by applying them to the five identified legislative responses to the COVID-19 pandemic which were implemented in Grenada over a two-year period that commenced on 25 March 2020 and ended on 16 May 2022 (the ‘pandemic period’). The characteristics and performance of each legislative measure will be ascertained through an examination of policy statements, the statute book, statistical data on the COVID-19 pandemic, academic writings and first-hand interviews of the former Attorney-General of Grenada. This article will assess the extent to which each legislative response to the COVID-19 pandemic has met the criteria, if at all.

This article will then comparatively analyse the findings of this assessment to measure the relative effectiveness, and consequently, the quality, of each response to determine which has been most effective. This analysis will also address the implications of the choice of legislative instruments and regimes on the overall effectiveness of the collective response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on this analysis, this article will then discuss and propose alternative legislative solutions and how they may have been implemented in Grenada to improve the overall effectiveness of the COVID-19 legislative response. -

B The Effectiveness Test

According to Mousmouti, ‘effectiveness has become an integral part of the values and principles that characterize legislative quality’.4x Maria Mousmouti, ‘The “Effectiveness Test” as a Tool for Law Reform’, IALS Student Law Review, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2014, p. 4. Quality itself is a broad term that is not only applicable to a wide range of contexts but is also typically assessed in relation to predetermined standards.5x Wim Voermans, ‘Concern About the Quality of EU Legislation: What Kind of Problem, by What Kind of Standards?’, Erasmus Law Review, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2009, p. 64. Expressed in simpler terms, ‘effectiveness expresses the extent to which a law can do the job it is intended to do and is considered the primary expression of legislative quality’.6x Helen Xanthaki, ‘Quality of Legislation: An achievable universal concept or a utopian pursuit?’ in Marta Travares Almeida (ed), Quality of Legislation, Nomos, 2011, p. 75. Measuring quality and evaluating effectiveness is traditionally linked either to policymaking or to the effectiveness and productivity of the public sector. As such, policies are appraised to assess their activities and the results of action.7x N. Staem, ‘Governance, Democracy and Evaluation’, Evaluation, Vol. 12, No. 7, 2006, p. 7. From the perspective of real-life results, effectiveness has been deemed the definitive indicator of legislative quality and the means of measuring effectiveness is evaluation.8x Mousmouti, 2012, p. 200.

The notion of effectiveness as an abstract concept has since been debunked and it is now articulated as a key characteristic of all legislative texts which is ultimately determined by the ‘purpose of legislation, its substantive content, its legislative expression, its overarching structure and real-life results’.9x Mousmouti, 2014, p. 5. These characteristics significantly influence a legislative instrument’s ability to achieve the desired results. Accordingly, not only is effectiveness a principle that guides law-making, but it is also now an established criterion for evaluating the results of such law-making.10x Luzius Mader, ‘Evaluating the Effects: A Contribution to the Quality of Legislation’, Statute Law Review, Vol. 22, 2001, p. 126.

The ‘effectiveness test’ is in essence Mousmouti’s attempt at translating the illusive theory of effectiveness into a ‘tangible and measurable concept’11x Mousmouti, 2014, p. 4. that can be used to not only measure but improve the overall quality of legislation. By definition, the test is ‘a logical exercise that examines the unique features of existing legislation and legislation being designed’,12x Mousmouti, 2012, p. 201. which views the legislative text as an entirety across its life cycle.13x Ibid., p. 203. Building on the rationale that effectiveness is the ultimate measure of legislative quality, Mousmouti asserts that an evaluation of such effectiveness comprises four key elements and takes into consideration the correlation and alignment among the purpose, content, structure (or context) and results of the law.

Purpose is the first element of the effectiveness test and sets the benchmark for what legislation aims to achieve.14x Mousmouti, 2014, p. 6. This limb of the test evaluates whether the law in question has a clear purpose, provides sufficient direction to its users and sets a clear and meaningful benchmark for what it intends to accomplish.15x Ibid. Although purpose can be expressed in law in a multitude of ways, the most effective expression of legislative purpose is a statement that combines narrow legal statements and broader policy objectives.16x Mousmouti, 2018, p. 453.

Content is the second element of the effectiveness test insofar as the substantive content and legislative expression determine how the law will achieve the desired results and how this is communicated to its users.17x Mousmouti, 2014, p. 6. This is determined by the drafter’s choice of rules, the manner in which they will be enforced and the positive and negative consequences that are attached to them.18x Mousmouti, 2018, p. 455. All of these choices inform the effectiveness of the legislative design as Mousmouti emphasizes that the extent to which a law will achieve the desired outcomes or results is determined largely in part by the ‘legislative techniques, enforcement mechanisms and legislative construction’ applied.19x Ibid.

Structure is the third element of the effectiveness test insofar as the overarching structure of the law in question determines how the new legislative provisions interact with the broader legal system.20x Mousmouti, 2014, p. 6. This element of the test has also been articulated by academics as ‘context’.21x Laingane Talia, ‘Unwrapping the Effectiveness Test as a Measure of Legislative Quality: A Case Study of the Tuvalu Climate Change Resilience Act 2019’, European Journal of Law Reform, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2021, p. 120. The interactions between legal messages may be direct or indirect; however, the effectiveness of these interactions is dependent on the ability of the respective groups of users of the legislation to locate, understand, apply and interpret these legal messages.22x Ibid.

Results comprise the fourth and final element of the effectiveness test which evaluates the real-life results of legislation23x Mousmouti, 2014, p. 6. and uses these results as a qualitative indicator of what the legislation has achieved. According to Mousmouti, the ‘moment of truth’ with respect to drafted legislation is when the outcomes and results indicate if and to what extent the drafter’s assumptions were supported and whether intentional or not, every legislative enactment generates results and outcomes.24x Mousmouti, 2018, p. 460. -

C Normative Legislative Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic

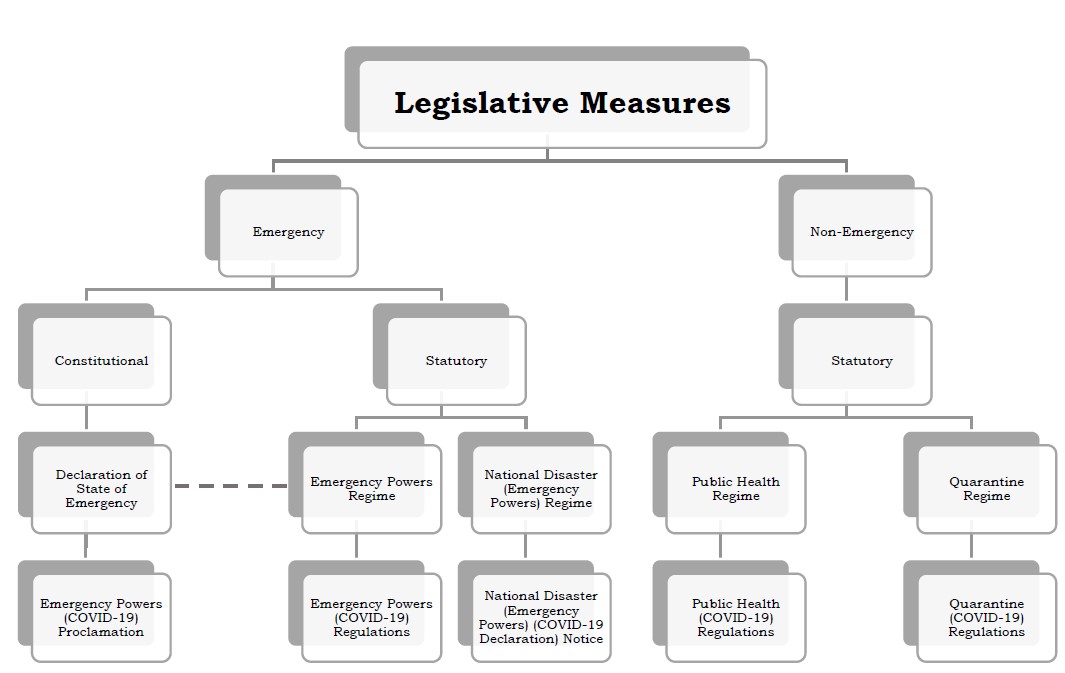

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of Grenada has engaged and implemented a series of normative legislative measures to guide the attitudes and behaviours of the population in a time of crisis. As demonstrated in Chart 1, these legislative responses include emergency and non-emergency measures provided for under the Grenada Constitution Order 1973 (the ‘Constitution’) as well as ordinary legislation.

Legislative Measures Implemented in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

As can be seen from the foregoing chart, four regulatory regimes were implemented to specifically address the issues stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic. It is debatable whether the constitutional declaration of a state of emergency can effectively be considered a stand-alone regime or a constituent of the Emergency Powers Regime due to the unique interdependency between the two (depicted by the dotted line). Nonetheless, it is evident that the legislative measures were encompassed in five crucial legislative instruments, notably, all of which take the form of subsidiary legislation:

Emergency Powers (COVID-19) Proclamation 2020, SR&O 12 of 2020 (the ‘EPCP’);

Emergency Powers (COVID-19) Regulations 2020, SR&O 13 of 2020 (the ‘EPCR’);

National Disaster (Emergency Powers) (COVID-19 Declaration) Notice 2020, SR&O 14 of 2020 (the ‘NDEPCN’);

Public Health (COVID-19) Regulations 2020, SR&O 59 of 2020 (the ‘PHCR’); and

Quarantine (COVID-19) Regulations 2020, SR&O 58 of 2020 (the ‘QCR’).

-

D Evaluation of Legislative Effectiveness

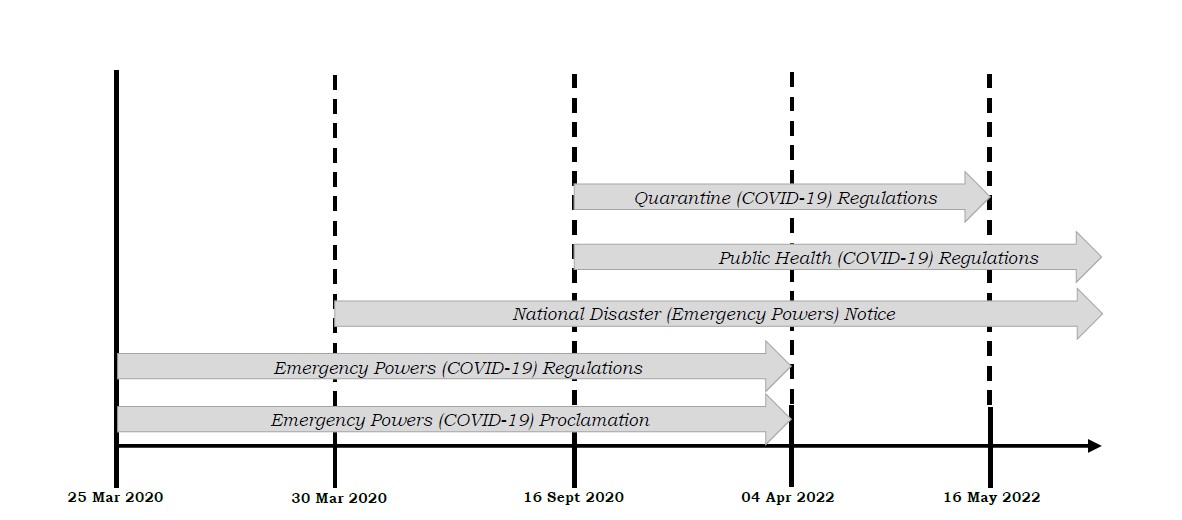

As can be seen from Chart 2, although the various legislative measures had idiosyncratic lifespans, all five legislative responses were effectively engaged during the period from 16 September 2020 to 4 April 2022 which represents a sizeable proportion of the pandemic period. Grenada is quite unique in this regard as most Commonwealth Caribbean countries only implemented one or two legislative measures and the few that implemented three or more did so consecutively rather than concurrently.

Considering the novel nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and the lack of judicial and legislative precedent, the legislative measures were implemented haphazardly on a trial-and-error basis. Moreover, the unexpected timeliness of the pandemic left no time for a prospective (ex ante) evaluation to be conducted to ensure that the selected legislative measures adhered to existing legal standards and procedural principles. Nor was there time to test the ensuing effects of ‘planned legislative interventions and retrospective evaluation’25x Mousmouti, 2012, p. 199. as required by such a prospective evaluation. Furthermore, although the overall response to the COVID-19 pandemic may be considered effective insofar as the spread of the virus among the population has been mitigated, an evaluation of the effectiveness of each individual measure is necessary to determine which of them contributed to this mitigation, if at all, and to what extent.

I Element 1 – Purpose

As declared by the Prime Minister of Grenada in his national address to the public on 13 March 2020, the Government’s primary objective as it pertained to COVID-19 was to ‘safeguard the population against the pandemic and contain the disease”.26x Available at: www.nowgrenada.com/2020/03/prime-ministers-address-on-covid-19/. Notably, this address was given prior to the first reported case of COVID-19 on the island and thus at this stage, all measures were intended to be preventative. However, once the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Grenada on 22 March 2020, the purpose broadened from just preventative to also remedial. As declared by the Governor-General on 25 March 2020,27x Emergency Powers (COVID-19) Proclamation 2020, SR&O 12 of 2020. the overarching objective of introducing legislative measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic was to slow the spread of COVID-19 among the population by:

substantially reducing the risk of transmission of COVID-19 and

identifying and treating those affected by COVID-19.

Accordingly, the implementation of the legislative responses discussed earlier was intended to meet the foregoing objectives. However, as these can be considered broad policy statements that go beyond the reach of legislation, each legislative measure should ideally be garnered to meet one or more of these objectives in a distinctive and very specific way. This is in line with Mousmouti’s assertion that the best way of expressing purpose in legislation is by combining narrow legal statements and broader policy objectives.28x Mousmouti, 2018, p. 453.

With respect to Acts of Parliament, statements of legislative purpose are generally incorporated as a preliminary provision termed a purpose or objectives clause.29x Helen Xanthaki, Thornton’s Legislative Drafting, 5th ed., Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013, p. 253. However, Thornton asserts that in respect of subsidiary legislation, a purpose clause ‘will rarely be desirable or necessary’, but rather the purpose of subsidiary legislation is encompassed within the respective principal Act and ideally so as any subsidiary legislative purpose which falls outside of the scope of the principal Act is at risk of being deemed ultra vires.30x Ibid., p. 531. However, preambles may be incorporated if they serve a useful purpose.31x Ibid. Accordingly, as all of the legislative responses to the COVID-19 pandemic take the form of subsidiary legislation, an examination of the purposes of their respective principal Acts is also necessary. In applying the ‘purpose’ element of the effectiveness test to the five identified legislative responses, it is evident that the similarly drafted legislative instruments expressed (or failed to express) purpose in similar ways.1 Procedural Legislative Purpose

The Constitution, as the supreme law of Grenada, is unlike any other legislative enactment and accordingly serves a much broader purpose. Although not expressly stated in the EPCP nor its respective enabling provision, it can be inferred that an overarching objective of declaring a constitutional state of emergency was to facilitate any derogations from the fundamental rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution, which, in accordance with section 14 of the Constitution, is only permitted during periods of emergency. However, it is debatable whether this can be considered a purpose or merely an anticipated consequence. In addition to this, the body of the EPCP clearly provides:

NOW THEREFORE, I CÉCILE LA GRENADE, Dame Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George, Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Governor-General in and over Grenada, acting in accordance with the advice of Cabinet, hereby declare that a state of emergency exists in the State of Grenada;

AND THAT the provisions contained in the Emergency Powers Act shall have continuing application

The objective of the EPCP as gleaned from the detailed provisions of the EPCP is twofold: (i) to declare that a state of emergency exists in Grenada by virtue of the occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic and (ii) to trigger the application of the provisions contained in the Emergency Powers Act 1987, CAP. 88 (the ‘EPA’). As the EPA authorizes the Cabinet to make regulations that derogate from the constitutionally protected fundamental rights and freedoms, the EPCP is a necessary procedural tool that safeguards the validity of any regime established under the EPA, rendering both measures interdependent. Accordingly, the purpose of this measure is merely procedural in triggering the declaration and application of an emergency regulatory regime. For the most part, this is expressed clearly and unambiguously within the instrument itself and leaves little room for uncertainty.

As the principal Act which enables the making of the NDEPCN, the purpose of the National Disaster (Emergency Powers) Act 1984, CAP. 203 (the ‘NDEPA’) is instrumental in ascertaining the purpose and scope of the NDEPCN. As the NDEPA contains no purpose clause, deference must be given to its long title which states that the purpose of the Act is to ‘make provision for the maintenance of supplies and services essential to the life of the community on the occurrence of a national disaster’. Although pragmatic, this statement is quite limited and offers inadequate information regarding the Act’s substantive purposes and objectives. Accordingly, the long title alone does not provide a meaningful benchmark for effectiveness and thus is of diminutive usefulness in the overall evaluation process.32x Mousmouti, 2018, p. 453. Section 3, which is the relevant enabling provision, offers further insight and provides that the Prime Minister may issue a notice such as the NDEPCN: (i) to declare that a national disaster has occurred in the State of Grenada and (ii) to trigger the application of the provisions contained in the NDEPA.

While the objective of the NDEPCN is also twofold, only one objective is expressed on its face and that is the declaration of the occurrence of a national disaster in the form of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, its purpose is also procedural in that it serves to trigger the application of the emergency regulatory regime under the NDEPA in accordance with section 3 thereof. The latter, however, is not expressed clearly and ambiguously within the Notice itself.

As both the EPCP and the NDEPCN are void of any substantive legal content, they serve no substantive legal purpose and only operate as procedural tools in ensuring that the overarching objective of slowing the spread of COVID-19 among the population is met. Their purposes are therefore linked to the specific purposes of the respective substantive regulatory regimes which each statutory instrument was intended to trigger.2 Substantive Legislative Purpose

As the principal Act which enables the making of the EPCR, the purpose of the EPA is instrumental in ascertaining the purpose and scope of the EPCR. As the EPA contains no purpose clause, deference must be given to its long title which states that the purpose of the Act is to ‘provide for matters relating to security during a period of emergency’. Although pragmatic, this statement is quite limited and offers inadequate information regarding the Act’s substantive purposes and objectives. Accordingly, the long title alone does not provide a meaningful benchmark for effectiveness and thus is of diminutive usefulness in the overall evaluation process.33x Ibid. Section 4, which is the relevant enabling provision, offers further insight and lists the different purposes for which regulations such as the EPCR may be made. Accordingly, it can be deduced that the EPCR was made to achieve the relevant objectives listed under this section, namely:

to control and regulate all food and liquor supplies;34x Emergency Powers Act 1987, s. 4(1)(a).

to impose on persons restrictions in respect of his or her employment, business, place of residence and association or communication with other persons;35x Ibid., s. 4(1)(c).

to prohibit persons from being outdoors between specified hours except under the authority of a written permit;36x Ibid., s. 4(1)(d).

to prohibit persons from travelling without permission;37x Ibid., s. 4(1)(f). and

to require persons to quit or not visit any place or area.38x Ibid., s. 4(1)(g).

When combined with the broader policy objective expressed in the EPA’s long title, these legal statements indicate how the EPCR contributes to the fight against COVID-19 both narrowly and broadly, which is a meaningful benchmark for evaluating legislative effectiveness. However, as there is nothing on the face of the EPCR which expressly links it to the foregoing objectives specifically, its purpose is neither clear nor unambiguous on its face and must be inferred.

As the principal Act which enables the making of the PHCR, the purpose of the Public Health Act 1925, CAP. 263 (the ‘PHA’) is instrumental in ascertaining the purpose and scope of the PHCR. As the PHA contains no purpose clause, deference must be given to its long title which states that the purpose of the Act is to ‘govern matters relating to Public Health’. This statement is quite broad and vague and offers inadequate information regarding the Act’s substantive purposes and objectives. Accordingly, it is of diminutive usefulness in the overall evaluation process as it does not provide a meaningful benchmark for effectiveness.39x Mousmouti, 2018, p. 453. Section 60, which is the relevant enabling provision, offers further insight and lists the different purposes for which regulations such as the PHCR may be made. Accordingly, it can be deduced that the PHCR was made to achieve the relevant objectives listed under this section, namely:to provide for any such matters or things as may appear advisable for preventing or mitigating COVID-19.40x Public Health Act 1925, s. 60(e).

This is a broad policy statement that can include a range of legal measures and is therefore an unmeasurable benchmark. In the absence of specific legal objectives, it is unclear how the PHCR is intended to contribute to the fight against COVID-19 and it runs the risk of encroaching on the objectives of other legislative measures or falling outside the ambit of the enabling Act. Accordingly, the purpose of the PHCR is neither clear nor unambiguous on its face and must be inferred.

As the principal Act which enables the making of the QCR, the purpose of the Quarantine Act 1947, CAP. 271 (the ‘QA’) is instrumental in ascertaining the purpose and scope of the QCR. As the QA contains no purpose clause, deference must be given to its long title which states that the purpose of the Act is to provide for ‘quarantine and similar matters’. This statement is quite broad and vague and offers inadequate information regarding the Act’s substantive purposes and objectives. Accordingly, it is of diminutive usefulness in the overall evaluation process as it does not provide a meaningful benchmark for effectiveness.41x Mousmouti, 2018, p. 453. Section 4, which is the relevant enabling provision, offers further insight and lists the different purposes for which regulations such as the QCR may be made. Accordingly, it can be deduced that the QCR was made to achieve the relevant objectives listed under this section, namely:to prevent danger to public health from ships, aircraft, persons or things arriving at any place [in Grenada];42x Quarantine Act 1947, s. 4(1)(a). and

to prevent the spread of infection by means of any ship, aircraft, person or thing about to leave any place [in Grenada].43x Ibid., s. 4(1)(b).

Unlike the other regulations made in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the QCR is unique in that it also includes the following preamble on its face:

WHEREAS it is necessary to prevent the spread of COVID-19 from persons arriving at any port by land or water;

The foregoing unambiguously expresses the purpose of the QCR (and inextricably links it to section 4 of the QA), which is to prevent the spread of COVID-19 from persons arriving at any port by land or water and is a legally oriented objective. However, the use of ‘WHEREAS’ impedes clarity as it introduces an antithesis in common language.44x Helen Xanthaki, Drafting Legislation: Art and Technology of Rules for Regulation, Hart Publishing, 2014, p. 136. When combined with the broader policy objective expressed in the QA’s long title, these legal statements indicate how the QCR contributes to the fight against COVID-19 both narrowly and broadly, which is a meaningful benchmark for evaluating legislative effectiveness.

3 Extrinsic Statements of Purpose

In addition to intrinsic statements of legislative purpose, a holistic outline of a law’s objectives is often detailed in the accompanying explanatory notes.45x Talia, 2021, p. 124. However, as it is not customary for subsidiary legislation to be accompanied by explanatory notes, other extrinsic sources were perused to ascertain the specific legislative objectives of the COVID-19 regulations. Official statements made by the Minister of Health during weekly post-Cabinet briefings and press statements identified the primary purpose of both the EPCR and the PHCR as restricting the movement and association of persons to reduce the risk of transmission of COVID-19.46x Available at: https://today.caricom.org/2020/05/25/covid-19-update-statement-minister-for-health-hon-nickolas-steele-grenada/. He also stressed the need to balance public health and safety against economic considerations.47x Ibid.

Similarly, the Minister of Health has stated that the QCR was made due to the need to identify and treat those affected by COVID-19 prior to and upon their arrival in Grenada and identified the need to boost the hospitality sector as an ancillary objective.48x Government of Grenada, ‘Re-evaluation of Covid-19 Protocols to Boost Hospitality Sector’ Government Information Service Newsletter, 21 September 2020, p. 8. Although these ministerial statements comprise legally oriented objectives and provide further clarity on the manner in which each instrument is intended to contribute to the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, the usefulness of these statements is also limited as they do not incorporate measurable targets against which their effectiveness can be evaluated. Moreover, as these statements are extrinsic to the regulations themselves, it is difficult for users to ascertain legislative purpose without looking outside the four corners of each instrument.II Element 2 – Content

1 Procedural Legislative Content

As deduced from the foregoing analysis of purpose, both the EPCP and NDEPCN merely served a procedural purpose and thus were void of any substantive legal content. Accordingly, the contents of these instruments were not intended to induce compliance or enforce a particular set of rules. At best, by design, they were intended to communicate specific declaratory messages. Nonetheless, it is imperative that these declaratory messages, albeit procedural, are ‘clear, precise and communicated in an understandable manner’.49x Maria Mousmouti, ‘Basic Concepts of Legislative Design’ Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, University of London (Lecture). Both the EPCP and NDEPCN comprise verbose paragraphs and archaic words and legalese, all of which should generally be avoided in the interests of clarity.50x Xanthaki, 2013, p. 58. However, as the target audience of both instruments was secondary users of legislation, such as lawyers and judges who apply, interpret and enforce the law, language does not inhibit the effective communication of the respective legal messages.

2 Substantive Legislative Content

The EPCR, although amended several times throughout the course of the pandemic, maintained a consistent legislative design and incorporated similar legislative techniques. Its provisions are both administrative and regulatory in nature, but primarily regulatory. Regulation 1 comprises preliminary provisions such as the short title and a sunset clause which serves to limit the duration of the regulations by establishing an expiry date. Most provisions, namely Regulations 2-14, are restrictive and prohibitory insofar as they:

restrict freedom of movement through the imposition of a curfew;

require persons to work remotely from home;

enforce the closure of businesses and other institutions;

impose physical distancing protocols;

restrict social activities; and

restrict international and domestic travel.

Regulation 15 is punitive as it imposes strict penalties for non-compliance with the foregoing prohibitions (a fine of one thousand dollars and imprisonment for twelve months) and Regulation 16 empowers the Commissioner of Police to issue guidelines to provide further clarification on the regulations. The subsequent amendments to the EPCR introduced further regulatory provisions, giving wider powers of enforcement to the police force and the Chief Medical Officer. The punitive measures of a fine and imprisonment under Regulation 15 were eventually replaced with a fixed penalty regime. Notably, the mandatory requirement to wear face masks in public was only introduced at the end of 2020 by way of an amendment to the EPCR.51x SR&O 73 of 2020.

The provisions of the PHCR are both administrative and regulatory in nature, but primarily regulatory. Notably, most provisions under these regulations regulate the same behaviours as those regulated under the EPCR in the same manner and even use identical provisions in some instances. Regulations 1-3 comprise preliminary provisions which provide for the short title, definitions and non-application of the regulations to individual cases of medical emergencies. Regulations 4-7 are restrictive and prohibitory insofar as they:require persons to wear masks in public;

impose physical distancing and sanitation protocols for businesses;

restrict the number of persons that may attend events or gatherings; and

regulate the operating hours of businesses and other institutions.

Regulations 8-13 are primarily administrative and identify the roles and responsibilities of the Minister of Health, the Chief Medical Officer, public health officers and environmental health officers with respect to conducting medical screenings and assessments and the respective procedures. Regulations 14-19 are punitive and establish a detailed fixed penalty regime for the payment of a fixed penalty of three hundred and fifty dollars on non-compliance with any of the foregoing provisions.

The provisions of the QCR are both administrative and regulatory. Regulations 1-4 comprise preliminary provisions which provide for the short title, definitions and the non-application of the regulations to children under a certain age. Regulations 5-7 are regulatory insofar as they:require persons to complete health declaration forms on arrival in Grenada;

require persons to undergo a prescribed COVID-19 testing procedure prior to and upon their arrival in Grenada; and

require persons who test positive for COVID-19 to enter and remain in a Government-approved place of observation and isolation for a prescribed period.

Regulation 9 is punitive as it imposes strict penalties for non-compliance with the foregoing prohibitions (a fine of ten thousand dollars per month). Regulation 10 empowers the Minister of Health to prescribe the COVID-19 tests to be taken and the respective periods of isolation and quarantine under the regulations and Regulation 11 empowers the Minister of Health to amend the Schedules by order.

Both the PHCR and the QCR followed a similar design and incorporated similar legislative techniques to the EPCR, arguably the result of all three being drafted by the same drafter. When considering the directives and recommendations of the WHO as it relates to measures that should be implemented by countries to curb the spread of COVID-19,52x Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/352339/WHO-2019-nCoV-ipc-guideline-2022.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. the choice of rules which permit and prohibit certain activities and behaviours under the foregoing legislative responses can be considered both appropriate and relevant in addressing the issues. Notably, the contents of both the EPCR and the PHCR are almost identical and the primary distinction between the two is the enforcement style used in respect of the sanctions applicable in the event of a breach of the regulations’ provisions. The EPCR incorporated strict penal sanctions of a fine and imprisonment that form part of the wider criminal law whereas the PHCR incorporated a less severe administrative penalty regime.

As can be expected from the implementation of such draconian measures, ensuring compliance with the regulatory regimes was an issue; however, the enforcement style used under the PHCR was more effective in this regard. The EPCR was met with widespread non-compliance on the part of the Grenadian population with hundreds of persons violating the imposed curfew daily.53x Available at: https://www.nowgrenada.com/2020/04/more-than-100-charged-within-first-3-days-of-mandatory-24-hour-curfew/. The punitive measures under Regulation 15 of the EPCR are unrealistic as imposing fines on so many persons or subjecting them to imprisonment would result in a heavily congested court system and overcrowded prison. Not only do these measures disproportionately impact vulnerable persons and communities, but they also defeat the overarching objective of limiting person-to-person contact to minimize the spread of COVID-19. As research has shown that prisons, due to the inherent mass gatherings of prisoners, are hotspots or hubs for the rapid transmission of COVID-19,54x David Lovatón, ‘Quarantine, State of Emergency, State of Enforcement, and the Pandemic in Peru’, Verfassungsblog, 26 April 2020, available at: https://verfassungsblog.de/quarantine-state-of-emergency-state-of-enforcement-and-the-pandemic-in-peru/. imprisonment is both unnecessary and counterproductive in the COVID-19 environment.

This was therefore a poorly designed legislative solution that did not reflect the institutional capacity of the court and prison systems, as well as the resources available to the police force. This resulted in the EPCR being poorly and inconsistently implemented, if it was even implemented at all, which is a clear indication that a law will be ineffective during its life cycle.55x Talia, 2021, p. 119. A similar disparity in the application of the COVID-19 laws in the United Kingdom has led to such measures being coined discriminatory in their application,56x Serdar Ünver, ‘Fighting COVID-19 – Legal Powers, Risks and the Rule of Law: Turkey’, Verfassungsblog, 15 April 2020, available at: https://verfassungsblog.de/fighting-covid-19-legal-powers-risks-and-the-rule-of-law-turkey/. which is concerning as an unequal application of the law flies directly in the face of the rule of law.

The alternative fixed penalty regime under the PHCR (similar to the regime regulating traffic offences) is a more suitable legislative technique whereby persons who violate the regulations will be issued a fixed penalty notice and required to pay the stipulated sum. While this alternative regime does not directly improve compliance, it significantly reduces the burden on the court and prison systems and ensures that the punitive measures are imposed stringently and consistently. This has deterrent effects, rendering it more effective in achieving the desired results.

Notably, the legislative design of the QCR retained the EPCR’s approach of imposing penal sanctions for violating its provisions. However, the QCR must be distinguished as it only applies to a small cross-section of the population, namely persons arriving in Grenada by air or sea. Moreover, in addition to the police, health officials, immigration officers and the security and staff at quarantine facilities are among the wide cross-section of users expected to enforce compliance with the measures under the QCR. Accordingly, the enforcement mechanisms are more reasonable in terms of resource availability, rendering the QCR more easily enforceable and effective. It is therefore unsurprising that non-compliance with the QCR was minimal.

As the same individual drafted all three instruments, the language used was consistent throughout. The main regulatory messages were communicated in a clear, precise and unambiguous manner and for the most part, legalese and archaic language were avoided. However, a key criticism raised by members of the population was that it was difficult to distinguish and isolate those messages addressed to them as primary users from the remainder of the legislative text. This failure to cater to the primary users of the legislation constitutes a flaw in the legislative design, as when a law’s subjects do not know how to comply with the law in question or encounter difficulties in interpreting the rules, the drafting is ineffective.57x Julia Black, ‘Critical Reflections on Regulation’, Australia Journal of Legal Philosophy, Vol. 27, 2002, p. 3. The legislative design would have been more effective if the regulatory messages under each instrument were grouped and separated into parts according to their intended audiences thereby adopting a user-centred layered approach.58x Xanthaki, 2014, p. 76.III Element 3 – Structure (Context)

In evaluating the effectiveness of the interaction and integration of the foregoing legislative responses, Mousmouti identifies three challenges that the drafter must address. In the drafting process, the drafter must ensure that the user can:

easily identify (locate) the law addressed to him or her within the legal system;

differentiate that particular law from competing ones; and

absorb whether and to what extent the law is amending, repealing or leaving competing laws untouched.59x Mousmouti, 2018, p. 464.

1 Identification, Differentiation and Absorption

Of the four elements of the effectiveness test, the structure of the different legislative responses may have had the most adverse impact on their overall legislative effectiveness. The novel and unexpected nature of the COVID-19 pandemic was such that it required immediate legislative responses to address the issue, leaving the legislative drafters little time to develop and design cohesive legislative instruments which gave ample consideration and attention to the needs of users to easily identify, differentiate and absorb the law as well as the mechanics of the existing legislative framework. As such, the structure of these responses suffered.

The haphazard publication of legislative instruments, such as the NDEPCN and the exorbitant succession of amendments to the EPCP, EPCR and PHCR (and to a lesser extent the QCR), is evidence that little consideration was given to the context in which the respective legislative instruments were being introduced and integrated into the current legal system, as well as how they would interact with each other. While several amendments are attributable to the need for the law to constantly evolve as the pandemic evolved, many of the amendments sought to correct flaws and errors in the original legislative designs.

Notwithstanding this, all COVID-19 legislation was made easily accessible to the public as the instruments were not only published in the Government Gazette but made available in real-time on the official Government of Grenada website, social media platforms, such as Facebook, digital and physical newspapers of daily circulation and broadcasted on the local news channels. As accessibility corresponds to the extent to which persons can physically get the legislation, find it and read it,60x John Burrows and Ross Carter, Statute Law in New Zealand, 4th ed., Lexisnexis, 2009, p. 141. it can be considered a key component of identification. Accordingly, it was easy for all users to identify or locate the COVID-19 laws relevant to them as the laws were made available and widely accessible on assorted mediums which cater to differences in the literacy levels and technological capabilities of all users.

However, due to the considerable amendments to the EPCP, EPCR and PHCR (and to a lesser extent the QCR), none of which were consolidated, navigating the legislative framework was quite difficult as users were required to address their minds to scores of separate instruments to ascertain the entirety of a single regulatory message. For example, users found themselves combing through multiple instruments in search of the ‘mask mandate’ or ‘social distancing protocols’ as it is not discernible at a glance which instruments correspond to which regulatory messages.

As all five legislative responses can collectively be considered ‘COVID-19 legislation’, none of them are truly stand-alone legislative instruments even though they were treated as such. Hence the eventual adoption by the public of the nomenclature ‘COVID-19 Laws’ to collectively refer to the NDEPCN, EPCP, EPCR, PHCR and QCR, notwithstanding the fact that they are five separate instruments. This undoubtedly renders it difficult for users to differentiate the five competing laws from each other, which in turn renders them less effective. Moreover, the repeated amendments to the EPCP, EPCR and PHCR resulted in dozens of regulations being made with similar names and having only their dates and citations as distinguishing features. As the amendments were never consolidated into a single instrument, users found it difficult to differentiate, for example, the fourth amendment to the EPCR from the fifteenth, without thoroughly assessing their respective contents.

The challenges in differentiating the various COVID-19 legislative measures from each other and distinguishing the various amendments also impact absorption. The numerous amendments render it difficult for users, especially lay users, to thoroughly absorb what the laws are amending, repealing or leaving untouched without further explanation. Secondary users of legislation also face difficulties in this regard. This is evident in the fact that health and police officers were chastised for applying legislative provisions inconsistently, as keeping abreast of the constant legislative changes proved challenging and often resulted in offenders being charged under unknowingly repealed provisions or even the wrong legislative instrument. The courts have also criticized the haphazard structure of the COVID-19 legislative measures and deemed them difficult to apply and interpret due to the endless torrent of amendments.

The configuration of amending legislation also contributes to this difficulty as amendments cannot effectively be comprehended by users without them being privy to the context and content of the principal legislative instrument. For this reason, consolidating the amendments to the EPCP, EPCR, PHCR and QCR would have been a more effective way of integrating these instruments into the legislative framework as users would not have to jump through additional hoops to decipher and absorb what is being amended, repealed or left untouched in respect of each instrument.2 Other Structural Concerns – Overlaps and Redundancies

A key indicator that the interaction among the legislative responses was not considered at the onset is that several overlaps and redundancies can be identified among the measures implemented and their respective provisions, the most glaring being demonstrated between the EPCP and NDEPCN as well as the EPCR and PHCR.

Considering the declaration of a constitutional state of emergency under the EPCP, it is arguable that there was no need to declare a statutory national disaster under the NDEPCN as both instruments served a similar purpose and were similar in content. Moreover, no regulations were made pursuant to the latter which indicate that the NDEPCN itself was unnecessary as the procedure that it set in motion was never completed. It was only after the NDEPCN was made that the policymakers realized that the implementation of two emergency power regimes was redundant and an Executive decision was made to proceed under the EPA as opposed to the NDEPA, as it was believed that regulations made by the entire Cabinet as opposed to solely the Prime Minister would be received more favourably by the public and appease any perception of autocracy.61x Interview with Dia Forrester, Attorney-General (Former), Office of the Attorney-General, Grenada, London, 12 August 2022. Moreover, as the former is founded on a constitutional declaration as opposed to a mere statutory declaration, it is believed to hold more weight and legitimacy, which is particularly relevant as the regime in question seeks to curtail constitutionally protected fundamental rights and freedoms.

As can be seen in the discussion of the respective contents of the EPCR and the PHCR, both instruments regulate quite a few of the same areas and activities, so much so that some of their provisions are identical.62x For example, both sets of Regulations contain identical provisions imposing physical distancing and sanitation protocols for businesses. As the legislative framework is already crowded with legal messages, the implementation of two separate pieces of legislation with identical legal messages is not only a waste of time and resources but a clear indication that the interaction between these two instruments was not considered at the initial design and development stages of the drafting process, rendering them ineffective as far as context is concerned.

Even more concerning are those provisions of the EPCR and the PHCR which regulate the same areas and activities, but with conflicting provisions. Regulation 20 of the EPCR is indicative of the conflicting nature of the interactions between the legal messages contained in both legislative instruments and it provides as follows:Where there is any inconsistency between the provisions of these Regulations and the Public Health (COVID-19) Regulations, 2020 the provisions of these regulations shall prevail to the extent of the inconsistency.

The need for the foregoing provision arose due to public confusion on the applicable rules relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. An example of this can be seen in an amendment to the PHCR63x SR&O 18 of 2022. which repealed the previously instated mandate to wear masks in public whereas the EPCR, which was simultaneously being enforced, expressly mandated the wearing of masks in public. Naturally, there were conflicting views among the population as to whether the mask mandate was still in effect. While Regulation 20 does technically remedy the conflict within the legislative framework, had the interactions between the two legislative instruments been thoroughly considered during the design and development stages of the drafting process, there would have been no conflict and no need for such a provision.

IV Element 4 – Results

Mousmouti stresses that the knowledge of legislative results is imperative to both the determination of the extent to which the objectives of a law have been achieved and the evaluation of its performance.64x Mousmouti, 2018, p. 458. However, in Grenada, the absence of a formal process for generating the results of legislation renders this the most difficult element to evaluate. There is no legal mandate for post-legislative scrutiny to be conducted nor does the legislation impose specific reporting and review requirements.65x Ibid.

1 Procedural Legislative Results

As both the EPCP and the NDEPCN were found to serve no substantive legal purpose and only operate as procedural tools in ensuring that the overarching objective of slowing the spread of COVID-19 among the population is met, the purpose of each instrument is easily analysed in results and outcomes by asking three simple questions:

Was a state of emergency/national disaster effectively declared in Grenada?

Does the EPA/NDEPA have continuing application?

Did the EPCP/NDEPCN trigger the implementation of a substantive regulatory regime under the EPA/NDEPA?

These are the benchmarks against which the effectiveness of these measures can be evaluated as they facilitate an easy juxtaposition of the initial objectives with the real-life legislative results.

With respect to the EPCP, it was effective in fulfilling its procedural mandate as a state of emergency was effectively declared in Grenada and the EPA had continuing application from the date of the issuance of the EPCP until its eventual revocation. The making of the EPCR is not only evidence of this continuing application, but also evidence that a substantive regulatory regime was implemented in the form of regulations made pursuant to section 4 of the EPA and that these regulations were triggered and facilitated by the EPCP.

With respect to the NDEPCN, it was only partially effective in fulfilling its procedural mandate as although a national disaster was effectively declared in Grenada and the NDEPA has continuing application to date, no further action was taken under the NDEPA. Accordingly, the NDEPCN did not trigger the implementation of a substantive regulatory regime under the NDEPA, notwithstanding the fact that this was the Executive’s original intention of declaring the national disaster in the first place.2 Substantive Legislative Results

None of the four established regulatory regimes include specific provisions which provide for monitoring of implementation or the reviewing of the intended results of each regime, which, according to some academics, renders the ‘evaluation of results to ascertain the effectiveness of the legislation impossible’.66x Talia, 2021, p. 139. Additionally, it is quite difficult to comparatively analyse the actual results achieved with those intended,67x Ibid. especially in the absence of detailed purpose clauses with measurable goals or targets. As stated earlier, the overarching objective of introducing legislative measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic was to slow the spread of COVID-19 among the population by:

substantially reducing the risk of transmission of COVID-19 and

identifying and treating those affected by COVID-19.

Statistical data collected and generated by the COVID-19 Data Repository68x Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. clearly demonstrates that there were spikes and declines in the rate of COVID-19 infections and COVID-19-related deaths in Grenada, with a significant decline seen towards the end of the pandemic period.69x Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/region/grenada. Although this data is indicative that the overarching objective was met, the lack of review mechanisms renders it impossible to ascertain which of the four regulatory regimes positively contributed to these results, if at all, and to what extent.

As declared by the Minister of Health, both the EPCR and the PHCR have the shared purpose of restricting the movement and association of persons to reduce the risk of transmission of COVID-19.70x Available at: https://today.caricom.org/2020/05/25/covid-19-update-statement-minister-for-health-hon-nickolas-steele-grenada/. From this statement, it can be gleaned that at least one of the intended results was a reduction in the risk of transmission of COVID-19. However, as there were no established mechanisms to monitor and review the implementation of the EPCR and the PHCR, there was nothing in place to trigger the collection of information and data specific to the measures in place under these instruments that allow for the identification and evaluation of results. Accordingly, there is no formal way to determine how effective the provisions of the EPCR and the PHCR have been in reducing the risk of transmission of COVID-19 since they were enforced.

Notably, the Cabinet convened weekly to discuss whether the regulations were engendering the intended results and based on the outcome of such discussions, the regulations were either left untouched, amended or repealed.71x Available at: www.nowgrenada.com/2020/03/prime-ministers-address-on-covid-19/. Therefore, while there was no legislated mechanism in place to monitor the results of the legislative responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was an informal, unregulated one. Thus, the frequency and nature of the amendments to the regulations may serve, to some extent, as indicators of their legislative effectiveness as far as the attainment of results is concerned. However, without further insight into the internal criteria and mechanisms used by the Cabinet to conduct these weekly evaluations, their usefulness is limited.

Although the fluctuations in the statistical data on confirmed COVID-19 cases and COVID-19-related deaths in Grenada are not an accurate benchmark against which the effectiveness of each legislative response can be evaluated, they do offer some useful insight. For example, from 16 May 2020, when the QCR was made up, until the end of the pandemic period, Grenada saw a drastic decline in the number of imported COVID-19 cases.72x Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/region/grenada. Moreover, only very few locally confirmed cases after 16 May 2020 were linked to any of these imported cases, which is indicative that the testing, quarantine and isolation measures implemented under the QCR were effective in achieving their specific purpose (as indicated by the preamble) of preventing the spread of COVID-19 from persons arriving at any port in Grenada by land or water. In fact, when the testing, quarantine and isolation measures were subsequently relaxed by virtue of an amendment to the QCR in December 2021, there was a notable increase in the number of imported COVID-19 cases, which is a further indication of a correlation between the two.Overall, none of the legislative responses were very effective in terms of results and outcomes and none of them incorporated specific reporting or review requirements in their respective provisions. Considering the wealth of COVID-19 statistics and data made available, such an exercise could be conducted quite practicably and substantively (as demonstrated in the preceding paragraph). However, it is evident that no consideration was given at the onset to the data and information required, how that data and information would be collected and the mechanisms through which the evaluation of results would be achieved.73x Talia, 2021, p. 122.

-

E Summary of Findings

Based on the foregoing assessment and notwithstanding the limitations to accurately evaluating legislative effectiveness, it is evident that as a legislative instrument, the QCR is most effective in comparison with the other legislative instruments; however, there is still much room for improvement as it relates to overall legislative quality. The QCR:

most clearly and unambiguously articulated its legislative purpose as it was the only substantive instrument that incorporated an express linkage to the regulation-making powers and objectives under its respective principal Act (purpose);

adopted a legislative design that incorporated rules and techniques that most appropriately addressed the COVID-19-related issues sought to be addressed by its legislative purpose (content);

was introduced and integrated into the legal system in a manner that ensured that it was most easily identified, differentiated and absorbed by users (structure or context); and

best generated the intended results and produced the desired effects which were easily assessed based on statistical data (results).

Although the EPCP can be considered just as effective as the QCR, if not more, as the EPCP was merely a procedural tool, its effectiveness must be considered in the context of the effectiveness of the regime which it sought to establish – the emergency regulatory regime of the EPCR. Unlike the QCR, the EPCR was not very effective as it:

did not clearly and unambiguously articulate its legislative purpose, leaving much to be inferred (purpose);

adopted a legislative design that continuously required reworking and amendment as the rules and techniques initially used were not the most appropriate to address the COVID-19-related issues sought to be addressed by its legislative purpose (content);

was not introduced and integrated into the legal system in a manner that ensured that it was most easily identified, differentiated and absorbed by users (structure or context); and

was initially found to be counterproductive and although it did generate some of the intended results post-amendment, the extent to which these results were attributable solely to these regulations was not assessable (results).

As the structure and content of the PHCR emulated that of the EPCR, it was found to be of similar legislative effectiveness. However, the legislative design of the PHCR comprised more appropriate rules and techniques which suggest that the drafter learned from her original mistakes and consciously sought to improve the content of the PHCR. Likewise, although the PHCR did generate some of the intended results, the extent to which these results were attributable solely to these regulations was not assessable.

The declared (emergency) regulatory regime that the NDEPCN sought to establish was the least effective, if it can even be considered effective at all, as it never came to fruition. Accordingly, the NDEPCN was the only legislative instrument that did not generate a significant proportion of its intended results.

With respect to overall quality, all five legislative instruments require considerable improvement, particularly as it pertains to the incorporation of content and structure which are user-centric and cater to the needs of laypersons as the primary users of legislation. Statements of purpose could be stated more clearly and unambiguously and the inclusion of review clauses, though not common in Grenada, should also be considered to facilitate the proper monitoring of implementation and evaluation of results.74x Mousmouti, 2018, p. 463.

Notwithstanding the foregoing ranking of legislative effectiveness, no one approach can be considered entirely effective at fulfilling the overarching purpose as the instruments were drafted in such a way that a collective effort was required. This is because the various health and safety measures recommended by WHO and other health organizations were scattered across the legislative instruments rather than consolidated. Moreover, the extent of overlap between the EPCR and the PHCR renders it impossible to assess, which better fulfilled the overarching objective and begs the question of whether both measures were even necessary or whether all the collective regulatory messages may have alternatively (and more effectively) been contained in one single instrument. -

F Alternative Legislative Solutions

I Primary Legislation vs. Subsidiary Legislation

Notwithstanding the array of choices available to drafters when considering the context in which a law will be introduced and integrated into the legislative framework,75x Ibid. it is evident that the drafters opted to utilize subsidiary legislation as opposed to primary legislation to regulate the behaviour of persons during the pandemic. The drafters also opted to engage multiple legislative measures (and consequently multiple legislative instruments) as opposed to just one. This was a unique approach in comparison with the approaches taken in other Commonwealth Caribbean jurisdictions which opted for one or two at most.

The choice of the drafters to introduce new laws in the form of regulations as opposed to an Act of Parliament was not solely dependent on the impact of this choice on legislative effectiveness but on external political pressures imposed on the Government by the public. Notably, Grenada’s Parliament attempted to pass a COVID-19 Bill in August 2020; however, due to strong objections and protests on the part of the public, the Bill was never passed. Criticisms of the Bill claimed that the Bill was ‘unwarranted, draconian, unconstitutional, bordering dictatorship and unheard of in the Commonwealth of nations’.76x Available at: https://www.nowgrenada.com/2020/08/grenada-covid-19-bill-2020-an-impetus-and-catalyst-for-legal-reforms/.

The content of the proposed Bill was in essence an amalgamation of the regulatory messages contained in the EPCR, PHCR and the QCR.77x SR&O 58 of 2020. The only substantial difference was the lack of flexibility and air of permanence associated with primary legislation in comparison with subsidiary legislation. This sparked much public concern due to the widely held perception that the rigid measures implemented to curb and contain the spread of COVID-19 were expected to be a temporary measure and had no place cemented in an Act of Parliament. Nonetheless, the choices to (i) regulate rather than legislate and (ii) make multiple regulations rather than consolidate, hindered the collective capacity of the legislative responses to be as effective in respect of predictability, accessibility, consistency, ease of application and timely achievement of the overarching purpose and mandate.78x Talia, 2021, p. 121.

Notably, the Grenadian drafters have indicated a preference for the use of subsidiary legislation as opposed to primary legislation with respect to the COVID-19 pandemic due to the ease with which the former can be amended – a necessary utility in the face of a constantly evolving crisis.79x Forrester, 2022. However, the inclusion of measures such as regulation-making powers and Henry VIII clauses in a COVID-19 Bill offer a conciliation between the safeguard of transparency attributable to an Act of Parliament and the time constraints brought about by the need to make recurrent changes to the regulatory messages as the pandemic evolves.II Consolidation as a Solution

Consolidation has been proposed as a solution to the multiple inconsistencies in the regulatory messages, whether the inconsistencies lie in the rules imposed, punitive measures applied or definitions of COVID-19-specific terminology.80x Mousmouti, 2018, p. 460. This is primarily because consolidation ensures that the set standards of behaviour are uniform. An example of this can be seen in the enactment of the Equality Act 2010 (UK) which merged several different legislative enactments together, each of which addressed specific areas of equality. Although the individual Acts offered enhanced protection from discrimination on the grounds of gender, disability, religion and age, among other factors, the protection offered was inconsistent. Accordingly, merging all legislation dealing with equality and non-discrimination in a single enactment was considered a viable solution to address the multiple intricacies that arose.81x Talia, 2021, p. 121.

As indicated by the Attorney-General, the sole reason for not introducing the COVID-19 legislation into the legal system as a consolidated Bill was the external political pressures imposed on the Government by the public to discard the proposed Bill.82x Forrester, 2022. However, as can be seen from the approaches taken by other regional counterparts, there were other solutions available:1 Solution 1 – Establishing a Single Regulatory Regime

Like Grenada, Barbados also opted to engage a regulatory regime to address the COVID-19 pandemic. Subsidiary legislation in the form of directives was made pursuant to the Emergency Management Act 2007 (Barbados) which comprised similar regulatory messages to those contained in Grenada’s EPCR, PHCR and QCR. It is evident that the establishment of three different regulatory regimes in Grenada arose out of necessity, as the scope of the EPA was not wide enough to address specific policy issues pertaining to public health that the Cabinet deemed imperative.

To address a similarly posed challenge, the Parliament of Barbados first amended the Emergency Management Act 2007 (Barbados) to broaden the scope of the Act to include the ‘declaration and management of public health emergencies’ such as COVID-19, thereby allowing the Executive to make directives addressing a broad range of areas and activities pertaining to COVID-19 and eliminating the need to engage other Acts or establish multiple regulatory regimes as was the case in Grenada.

2 Solution 2 – Establishing a Single Legislative Regime

At the end of the first year of the pandemic, Saint Christopher and Nevis enacted the COVID-19 (Prevention and Control) Act 2020 (SKN) which was almost identical in content and structure to the proposed COVID-19 Bill that Grenada’s Parliament attempted and failed to pass. This failed Bill is confirmation that the trust of the citizenry is ‘critical for governments to do their job effectively and attack challenging issues’,83x Mark Evans, Will Jennings and Gerry Stoker, ‘How Does Australia Compare: What Makes a Leading Democracy?’, Democracy 2025, Vol. 6, 2020, p. 6. especially in circumstances where the population is being asked to sacrifice their fundamental rights and freedoms. To reinforce this trust and curtail the risk of legislators overestimating the risk at hand,84x John Ip, ‘Sunset Clauses and Counterterrorism Legislation’, Public Law, Vol. 74, 2012, p. 1-26. it has been posited that an appropriate review mechanism should be incorporated into such a Bill as a means of ensuring its critical scrutiny.85x Hon Kate Doust MLC and Sam Hastings, ‘Legislative Scrutiny in Times of Emergency’, European Journal of Law Reform, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2020, p. 373.

As the primary concern of those opposed to the Bill was the lack of flexibility and air of permanence associated with primary legislation, the inclusion of a sunset clause in the proposed Bill would have provided a counterbalance by guaranteeing the temporary nature of the COVID-19 emergency legislation.86x Lianne van Kalken and Evert Stamhuis, ‘Digital Equals Public’, European Journal of Law Reform, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2020, p. 389. A sunset clause is defined by Kouroutakis as a ‘statutory provision providing that a particular law will expire automatically on a particular date unless it is re-authorized by the legislature’.87x Antonios Kouroutakis, The Constitutional Value of Sunset Clauses: An Historical and Normative Analysis, Routledge, 2017, p. 3. Over the course of history, such a clause has been used as a legislative bargaining tool to garner agreement88x Ittai Bar-Siman-Tov, ‘The Lives and Times of Temporary Legislation and Sunset Clauses’, American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 66, No. 2, 2018, p. 453. and would therefore be useful in garnering the support, or at least the acquiescence, of the Grenadian population in the passage of such a controversial Bill. The approach of including a sunset clause in COVID-19-related legislation was found to be effective in the Netherlands as it resulted in the successful enactment of the Temporary Act 2020 (The Netherlands), which was initially opposed but ultimately passed based on its temporal nature. In fact, it has been suggested that any statute which intervenes in an emergency or crisis is expected to be temporary.89x van Kalken and Stamhuis, 2020.Either of the foregoing solutions would have eliminated the need to engage any other legislative enactment and would have rendered it much easier for users to identify, differentiate and absorb the regulatory messages applicable to them as all the relevant information would be contained in a single instrument. A consolidated approach would have been more structurally or contextually effective in Grenada as it would have also ensured a more seamless and less haphazard integration and introduction of COVID-19-specific legislation into the legislative framework without significantly encroaching on an already crowded legal system. Moreover, the inclusion of a sunset clause facilitates legislative scrutiny and review processes which are imperative in effectively evaluating the results and outcomes of legislation ex post.90x Joelle Grogan, ‘Approach with Caution: Sunset Clauses as Safeguards of Democracy?’, European Journal of Law Reform, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2021, p. 147.

III Emergency Regime vs. Ordinary Regime

Having established that proceeding under a single statutory regime would have been most effective, the question of whether an emergency statutory regime or an ordinary statutory regime would be most suitable arises. The Venice Commission has suggested that the use of emergency powers is only justified if they are necessary to overcome the exceptional situation, proportional, limited in time and subject to effective judicial and parliamentary control.91x Franklin De Vrieze and Constantin Stefanou, ‘Are Emergency Measures in Response to COVID-19 a Threat to Democracy?’, European Journal of Law Reform, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2020, p. 335.

As the use of ordinary non-emergency legislation has proven to be just as effective in controlling the pandemic in other jurisdictions, it is arguable that the use of emergency statutory regimes in Grenada was unnecessary. However, it cannot be ignored that the use of pre-existing ordinary legislation is not without its challenges; the primary concern is that of legislative quality since pre-existing legislation was often ‘unsuitable and necessitated reform to account for the unique challenges that arose from the pandemic’,92x Joelle Grogan, ‘States of Emergency’, European Journal of Law Reform, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2020, p. 344. with such reform habitually being hurried and haphazard.93x Julinda Beqiraj, ‘Italy’s Coronavirus Legislative Response: Adjusting Along the Way’, Verfassungsblog, 08 April 2020, available at: https://verfassungsblog.de/italys-coronavirus-legislative-response-adjusting-along-the-way/.

Greene suggests that the declaration of a state of emergency should act almost as ‘a quarantine on the use of those powers’,94x Alan Greene, ‘Derogating from the European Convention on Human Rights in Response to the Coronavirus Pandemic: If Not Now, When?’, EHRLR, Vol. 4, 2020, p. 266. and the preferred framework from the perspective of the rule of law and democratic legitimacy is a two-step process whereby the Executive may declare a state of emergency that must be confirmed within a reasonable time by the Legislature.95x Grogan, 2020, p. 340. This is in line with the stringent requirements imposed under section 17 of the Constitution and which have proven to be quite time-consuming and onerous on not only the Executive and the Legislature that are required to convene every time an extension is required, but also the drafters who are responsible for drafting the statutory instruments to extend the duration of the constitutional state of emergency, which, as can be seen from the timeline of legislative responses, happened quite frequently during the course of the pandemic.

However, these constitutional safeguards ensure that the derogations from the constitutionally protected rights of freedom of movement and freedom of assembly are not abused by the Executive. Nevertheless, the lack of a true separation of powers between the Executive and Legislative arms of Grenada’s Government and the absence of an opposition renders these safeguards and limits on Executive power ‘just words on paper’.96x Ibid., p. 342. Even so, the availability of judicial review of the exercise of emergency legislative powers has not been curtailed in any way and therefore provides an additional layer of scrutiny.

In essence, while the use of ordinary legislative powers may be preferred on the basis that they better safeguard democracy, the sole engagement of ordinary legislative powers is likely to circumvent the scrutiny and constraints that typically accompany the use of emergency legislative powers.97x Ibid., p. 345. As such, the use of one regime over the other does not render a greater or lesser likelihood of abuse of power98x Ibid., p. 354. and so one regime cannot objectively be considered more effective especially when Executive overreach in Grenada is hardly a concern. In fact, a regime comprising elements of both emergency and ordinary legal powers has been proven most effective in jurisdictions that have seen some of the most positive responses to the pandemic such as New Zealand.99x Dean Knight, ‘Lockdown Bubbles through Layers of Law, Discretion and Nudges – New Zealand’, Verfassungsblog, 7 April 2020, available at: https://verfassungsblog.de/covid-19-in-new-zealand-lockdown-bubbles-through-layers-of-law-discretion-and-nudges/. Regardless of whether an emergency statutory regime, an ordinary statutory regime or a combination of both is established, it is factors such as ‘legal certainty, transparency, clear communication and early reaction’100x Grogan, 2020, p. 354. that determine its overall effectiveness and not the choice of regime per se. -

G Conclusion

This article has effectively proven that the non-emergency statutory measures were a more effective legislative response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Grenada insofar as their purpose, structure, content and results were better aligned and consistent resulting in higher-quality legislation in comparison with the constitutional and statutory emergency measures which were also implemented during the pandemic. This was proven based on an evaluation of the extent to which each legislative response met Mousmouti’s criteria of legislative quality, collectively characterized as the ‘effectiveness test’.101x Mousmouti, 2012, p. 201. A comparative analysis of the results of this evaluation revealed that the extent to which each legislative response met Mousmouti’s criteria varied significantly. It was determined that the QCR was the most effective legislative instrument, followed by the EPCP, EPCR and PHCR, which were found to be of similar legislative effectiveness. The NDEPCN was the least effective as it was the only legislative instrument that did not generate a significant proportion of its intended results.

The analysis also revealed that notwithstanding their comparative effectiveness, there was still room for much-needed improvement of the overall legislative quality of all five instruments. It was also revealed that the collective regulatory messages may have been alternatively and more effectively contained in one single instrument. Accordingly, consolidation of the regulatory messages in a single regime (either legislative or regulatory) was proffered as a superior alternative course of action which, if implemented properly, would have likely improved the overall effectiveness of Grenada’s COVID-19 legislative response. Notably, the choices of utilizing primary legislation versus subsidiary legislation or establishing an emergency statutory regime versus an ordinary statutory regime were found to have little bearing on legislative effectiveness and can instead be considered matters of personal preference. However, other factors, such as legal certainty, transparency, clear communication and early reaction, were the most critical indicators of legislative effectiveness.

Overall, the application of the elements of the effectiveness test to the five legislative responses to the COVID-19 pandemic is confirmation of the applicability of the test to Grenada’s legislative framework and its usefulness in facilitating an exercise of post-legislative scrutiny. The importance of the relationship between the various phases of the life cycle of rules102x Ibid., p. 205. was clearly demonstrated and the failure to thoroughly consider potential challenges that may have arisen in implementing these legislative responses that ultimately resulted in poor-quality legislation.

Noten

-

2 Maria Crego and Silvia Kotanidis, ‘Emergency Measures in Response to the Coronavirus Crisis and Parliamentary Oversight in the EU Member States’, European Journal of Law Reform, Vol. 22, No. 4, 2020, p. 416.

-

3 Maria Mousmouti, ‘Operationalising Quality of Legislation through the Effectiveness Test’, Legisprudence, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2012, p. 201.

-

4 Maria Mousmouti, ‘The “Effectiveness Test” as a Tool for Law Reform’, IALS Student Law Review, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2014, p. 4.

-

5 Wim Voermans, ‘Concern About the Quality of EU Legislation: What Kind of Problem, by What Kind of Standards?’, Erasmus Law Review, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2009, p. 64.

-

6 Helen Xanthaki, ‘Quality of Legislation: An achievable universal concept or a utopian pursuit?’ in Marta Travares Almeida (ed), Quality of Legislation, Nomos, 2011, p. 75.

-

7 N. Staem, ‘Governance, Democracy and Evaluation’, Evaluation, Vol. 12, No. 7, 2006, p. 7.

-

8 Mousmouti, 2012, p. 200.

-

9 Mousmouti, 2014, p. 5.

-

10 Luzius Mader, ‘Evaluating the Effects: A Contribution to the Quality of Legislation’, Statute Law Review, Vol. 22, 2001, p. 126.

-

11 Mousmouti, 2014, p. 4.

-

12 Mousmouti, 2012, p. 201.

-

13 Ibid., p. 203.

-

14 Mousmouti, 2014, p. 6.

-

15 Ibid.

-

16 Mousmouti, 2018, p. 453.

-

17 Mousmouti, 2014, p. 6.

-

18 Mousmouti, 2018, p. 455.

-

19 Ibid.

-

20 Mousmouti, 2014, p. 6.

-

21 Laingane Talia, ‘Unwrapping the Effectiveness Test as a Measure of Legislative Quality: A Case Study of the Tuvalu Climate Change Resilience Act 2019’, European Journal of Law Reform, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2021, p. 120.

-

22 Ibid.

-

23 Mousmouti, 2014, p. 6.

-

24 Mousmouti, 2018, p. 460.

-

25 Mousmouti, 2012, p. 199.

-

26 Available at: www.nowgrenada.com/2020/03/prime-ministers-address-on-covid-19/.

-

27 Emergency Powers (COVID-19) Proclamation 2020, SR&O 12 of 2020.

-

28 Mousmouti, 2018, p. 453.

-

29 Helen Xanthaki, Thornton’s Legislative Drafting, 5th ed., Bloomsbury Publishing, 2013, p. 253.

-

30 Ibid., p. 531.

-

31 Ibid.

-

32 Mousmouti, 2018, p. 453.

-

33 Ibid.

-

34 Emergency Powers Act 1987, s. 4(1)(a).

-

35 Ibid., s. 4(1)(c).

-

36 Ibid., s. 4(1)(d).

-