An Ex Post Impact Assessment of Municipal Restructuring in Finland

-

A Introduction

For several decades, there has been a prevailing perception of considering law drafting and its paragon on the principles of the rational model. The central role of the rational model can be detected, for example, in the recommendations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Commission’s Better Regulation policy.1x See, e.g., European Court of Auditors, Ex-post Review of EU Legislation: A Well-established System, But Incomplete, Special Report 16, 2018; OECD, Regulatory Impact Assessment, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, 2020. The relevance of the model is also reflected in the law-drafting processes of individual countries. For example, in Finland, the impact assessment and law-drafting guidance are, in several respects, based on the principles of the model.

In the rational model, a law-drafting process begins with a problem definition. In the second phase, the legislature appraises the impacts of different alternative regulatory options by evaluating the costs and benefits of each of the alternatives and, finally, implements the chosen (best) alternative. The impact assessment process occurring before the implementation of the chosen regulation is called an ex ante impact assessment. After the regulatory actions have been implemented, it is essential to evaluate the actual effects. This kind of regulatory appraisal is called an ex post impact assessment. The ex post impact assessment (or evaluation) improves the quality of forthcoming ex ante analysis by giving information about the failures of the implemented policies and programmes. If necessary, the tracked programme failure might lead to modification or abolishment of a given regulation. Thus, the policy learning from ex post impact assessments to amend existing regulations is an integral part of the law-drafting process.2x L. Mergaert & R. Minto, ‘Ex Ante and Ex Post Evaluations: Two Sides of the Same Coin. The Case of Gender Mainstreaming in EU Research Policy’, European Journal of Risk Regulation, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2015, pp. 48-49; C.V. Patton & D.S. Sawicki, Basic Methods of Policy Analysis and Planning, 2nd ed., Prentice Hall, 1993, p. 46-52, 63; P. Popelier & V. Verlinden, ‘The Context of the Rise of Ex Ante Evaluation’, in J. Verschuure (Ed.), The Impact of Legislation. A Critical Analysis of Ex Ante Evaluation, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2009, p. 18; J.A. Schwartz, ‘Approaches to Cost-benefit Analysis’, in C.A. Dunlop & C.M. Radaelli (Eds.), Handbook of Regulatory Impact Assessment, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2016, pp. 35-41; K. van Aeken, ‘From Vision to Reality: Ex Post Evaluation of Legislation’, Legisprudence, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2011, pp. 45, 51; H. Wollman, ‘Policy Evaluation and Evaluation Research’, in F. Fischer & G.J. Miller & M.S. Sidney (Eds.), Handbook of Public Policy Analysis. Theory, Politics, and Methods, CRC Press, 2007, p. 393.

The necessity for ex post impact assessments has been apparent, for example, in the local government sector, as in several countries the regulator has considered municipal mergers as a panacea for improving the financial position of local governments. However, various local government merger reforms are one example of inadequately assessed regulatory reforms. According to Tavares (2018), most of the merger reforms implemented in this millennium in Western Europe have not been supported by rigorous empirical research and reliable data analysis, as academic research has been having ‘a very limited’ influence on governmental reforms.3x A.F. Tavares, ‘Municipal Amalgamations and Their Effects: A Literature Review’, Miscellanea Geographica – Regional Studies on Development, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2018, p. 5.

In Finland, the most comprehensive merger reform has been the so-called PARAS reform, which took place between 2007 and 2013. The purpose of the reform was to strengthen municipal and service structures by merging municipalities and forming cooperation districts. The main objectives of the reform were to enhance the productivity of municipal service production, moderate the expenditure growth of municipalities and form ‘a vital municipal structure’. The PARAS reform centralized the Finnish municipal structure through 68 municipal mergers, and the total number of municipalities decreased during that period from 431 to 320.

The PARAS reform was criticized for the lack of use of scientific evidence in the decision-making process.4x V. Vihriälä, ‘Politiikka-analyysi (talous)politiikassa’, in S. Ilmakunnas & T. Junka & R. Uusitalo (Eds.), Vaikuttavaa tutkimusta – miten arviointitutkimus palvelee päätöksenteon tarpeita?, VATT-julkaisuja 47, Government Institute for Economic Research, 2008, p. 27. According to one of the main law-drafters, the decision-making was not based on a proper ex ante consideration of alternative regulatory options.5x A. Valli-Lintu, Sote- ja kuntarakenteen pitkä kujanjuoksu, Kunnallisalan kehittämissäätiön julkaisu 10, 2017, p. 8. However, as the rational model suggests, it is important to evaluate later what has happened. Hence, this article aims to conduct an ex post impact assessment about the achievement of the objectives set for the PARAS reform. The research question is the following: Have the objectives set for the PARAS reform been achieved? In practice, this study analyses the causal link between municipal mergers and the objectives of forming a vital municipal structure, enhancing productivity and moderating the expenditure growth of municipalities. The causal link is analysed by using the DiD strategy by comparing merged municipalities with a matched group of municipalities that did not merge during the study period.

This article aims to produce scientific evidence about the impacts of municipal mergers to strengthen the evidence base of the ex ante impact assessments of forthcoming reforms. Furthermore, the Finnish experiences can be utilized not only in Finland but also on a more general level, as municipal mergers have been resorted to across the world to improve the financial position of local governments. The choice of the outcome variables under analysis is based on both the legislative objectives of the PARAS reform and the previous merger literature. In empirical legal research, the researcher can use regulatory objectives as standards to investigate whether policy goals have been achieved.6x S. Taekema, ‘Theoretical and Normative Frameworks for Legal Research: Putting Theory into Practice’, Law and Method, 2018, pp. 1-17. In this study, the legislative objectives of the PARAS reform have defined the choice of subjects under analysis and the precise outcome variables. Municipal mergers have many different impacts, and the study must be delimited to some point. In the case of ex post impact assessments, the most obvious delimitation is to focus on analysing the achievement of the main objectives. The choice of the outcome variables is also attached to the previous merger literature. For vitality effects, the impacts of PARAS mergers are analysed on business activities, and for expenditure and productivity effects on comprehensive schooling. As mentioned in the third section of this article, previous research has only touched on these topics.

This article is based on the author’s PhD thesis, which is published in Finnish.7x N. Vartiainen, Suurempi kunta on elinvoimaisempi kunta? Lainsäädännön jälkikäteinen vaikutusarviointi päätöksenteon tukena, Publications of the University of Eastern Finland. Dissertations in Social Sciences and Business Studies 254, 2021a. The purpose of this article is to bring the most central results of the thesis to the international audience. The structure of the article is the following. The next section briefly introduces the local government structure reforms in Finland, concentrating especially on the reform under analysis, the PARAS reform. Section three reviews the literature on the economic theoretical arguments for increasing municipal size and the empirical findings of the impacts of municipal mergers. Data and methods are presented in section four, and the results in section five. Section six discusses the results and discloses what can be learned from the findings. -

B Local Government Restructuring in Finland

For several decades, there has been a worldwide tendency towards bigger local government units. This tendency has been prominent, among the others, in Canada,8x T.W. Cobban, ‘Bigger Is Better: Reducing the Cost of Local Administration by Increasing Jurisdiction Size in Ontario, Canada, 1995-2010’, Urban Affairs Review, Vol. 55, No. 2, 2019, pp. 462-500. Denmark,9x J. Blom-Hansen, K. Houlberg & S. Serritzlew, ‘Size, Democracy, and the Economic Costs of Running the Political System’, American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 58, No. 4, 2014, pp. 790-803. Germany,10x S. Blesse & T. Baskaran, ‘Do Municipal Mergers Reduce Costs? Evidence from a German Federal State’, Regional Science and Urban Economics, Vol. 59, 2016, pp. 54-74. Israel,11x Y. Reingewertz, ‘Do Municipal Amalgamations Work? Evidence from Municipalities in Israel’, Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 72, No. 2-3, 2012, pp. 240-251. Japan,12x H. Hirota & H. Yunoue, ‘Evaluation of the Fiscal Effect on Municipal Mergers: Quasi-experimental Evidence from Japanese Municipal Data’, Regional Science and Urban Economics, Vol. 66, 2017, pp. 132-149. the Netherlands13x M.A. Allers & J.B. Geertsema, ‘The Effects of Local Government Amalgamation on Public Spending, Taxation, and Service Levels: Evidence from 15 Years of Municipal Consolidation’, Journal of Regional Science, Vol. 56, No. 4, 2016, pp. 659-682. and Sweden.14x B.T. Hinnerich, ‘Do Merging Local Governments Free Ride on Their Counterparts When Facing Boundary Reform?’, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 93, No. 5-6, 2009, pp. 721-728. Finland has not been an exception, and since the 1960s, the policy trend has been to form bigger units on the local government level. The first large-scale reform was ‘the Major Local Government Reform’, which was carried out between 1961 and 1982. The reform included minimum population base objectives and sought to decrease the number of municipalities. At the end of the reform, the number of municipalities had decreased from 548 to 461. The next substantial scheme was the PARAS reform, which took place between 2007 and 2013. Between these reforms, the government spurred municipal mergers by, for example, merger grants, but the spurring was not as prominent as it was during the PARAS reform. Between 1983 and 2006, the number of municipalities decreased by 30, from 461 to 431.

According to the law-drafting documents of the PARAS reform, the rationale behind the mergers was related to the changes observed in the operating environment in the municipal sector: population ageing, increased demand for services, internal migration and financial pressures. These changes were considered to be especially challenging for low-populated municipalities. The main purposes of the reform were to enhance the productivity of the production of municipal services, moderate the expenditure growth of municipalities, and form ‘a vital municipal structure’. The key means to achieve these goals was to spur municipal mergers through merger grants and other incentives and to set minimum population requirements, which meant a population base of about 20 000 inhabitants for social and healthcare services and about 50 000 for vocational education.15x Government bill 155/2006, Hallituksen esitys Eduskunnalle laiksi kunta- ja palvelurakenneuudistuksesta sekä laeiksi kuntajakolain muuttamisesta ja varainsiirtoverolain muuttamisesta. The PARAS reform triggered ‘a merger wave’, and a total of 68 municipal mergers were produced during the reform between 2007 and 2013. The number of municipalities decreased to 320, which meant a reduction in the number of municipalities by 111.

Although the number of municipalities decreased substantially during the PARAS reform, the legislature was still not satisfied with the formation of the Finnish municipal structure. The structure was still considered to be too fragmented, and an insufficient number of mergers were accomplished in urban areas and in areas where economic reasons or regional circumstances would have justified the mergers.16x Government bill 31/2013, Hallituksen esitys eduskunnalle laeiksi kuntajakolain muuttamisesta ja väliaikaisesta muuttamisesta, kuntajakolain eräiden säännösten kumoamisesta sekä kielilain muuttamisesta. Thus, the government decided to launch a new reform to achieve a new merger wave. This reform was called ‘the Reform of the Structure of Local Government’, and it entered into force in July 2013. However, this reform did not achieve its targets of a new merger wave, and after 2013 the number of Finnish municipalities has decreased only by eleven, to 309 municipalities by now (2023).

One reason behind the failure of the reform was that the focus of restructuring Finnish local governments began to shift from municipal mergers to restructuring the largest municipal service sector, social and healthcare. The reorganization of social and healthcare services collapsed multiple times owing to constitutional issues, but, finally, in June 2021, the reorganization was approved by the Finnish parliament. As a result, the social and healthcare services were transferred from municipalities’ responsibility to newly established regions from the beginning of 2023. The shifting of social and healthcare services stresses the position of schooling in municipal service production, as it lifted the schooling sector as the largest municipal service sector.

The ex post impact assessment in this study focuses on the PARAS reform. The PARAS reform offers a useful opportunity for a quantitative ex post analysis as the reform produced several mergers in a short period. The research subjects under analysis have been chosen based on the objectives set for the reform. Thus, the impacts of the mergers are analysed on vitality, expenditure growth and productivity.17x In addition to municipal mergers, the PARAS reform also produced several cooperation districts, especially in the social and healthcare sector. However, the impacts on cooperation districts are not within the scope of this study.

Vitality is a broad concept, but in this study it is examined from a business activities perspective. That is because, according to the law-drafting documents, there is a strong linkage between vitality and the location decisions of business activities.18x Government bill 125/2009, Hallituksen esitys Eduskunnalle kuntajakolaiksi, p. 48; Administration Committee report 31/2006, Hallintovaliokunnan mietintö hallituksen esityksestä (HE 155/2006 vp) laiksi kunta- ja palvelurakenneuudistuksesta sekä laeiksi kuntajakolain muuttamisesta ja varainsiirtoverolain muuttamisesta; Finnish Ministry of Finance, Elinvoimainen kunta- ja palvelurakenne. Osa I Selvitysosa, Kunnallishallinnon rakennetyöryhmän selvitys, Valtiovarainministeriön julkaisuja 5a, 2012, pp. 17, 158. The location decisions of business activities are measured based on three indicators: population change, the change in the number of private-sector jobs, and the change in the number of businesses. The choice of these indicators is based on the definition of a vital municipal structure by the Finnish legislature. According to the report from the Finnish Ministry of Finance (2012), the vital municipal structure is connected to population growth and business activities. Vitality is also dependent on the ability to create new jobs and allure employees to the municipality.19x Finnish Ministry of Finance, 2012, pp. 17, 158. In Finnish decision-making, there has been a belief that increasing municipal size could have a positive impact on the attractiveness of localities.20x Government bill 31/2013. Furthermore, the necessity for municipal mergers has often been justified by business arguments, and the improvement of business activities has had a central role in many intermunicipal investigations exploring the possibility of a merger.21x A. Koski, A. Kyösti & J. Halonen, Opittavaa kuntaliitosprosesseista. META-arviointitutkimus 2000-luvun kuntaliitosdokumenteista, Suomen Kuntaliitto, 2013, p. 106.

The impacts considering expenditure growth and productivity are studied with reference to one municipal service sector: comprehensive schooling. The shift of social and healthcare services justifies studying the impacts on schooling, as it has been turned into the largest municipal service sector. In the Finnish municipal system, the schooling sector includes various subsectors (as early childhood education, comprehensive schooling and senior secondary schools). This study focuses on comprehensive schooling, which is the largest domain in the schooling sector. The focus on comprehensive schooling was considered to be appropriate owing to the availability of proper research data as the complexity related to the organization and financial statistics of senior secondary schools disrupts to some extent the municipality-specific statistics in that sector.

The achievement of expenditure and productivity objectives in comprehensive schooling is measured as the growth of expenditures per pupil and per teaching hours. The report of the PARAS reform’s schooling monitoring programme stated that productivity is frequently measured as a relationship between inputs and outputs.22x Finnish Ministry of Education, Koulutuksen seurantaohjelma. Kunta- ja palvelurakenneuudistuksen koulutuspoliittisen arvioinnin sekä eduskunnalle laadittavan koulutuksen arviointikertomuksen tueksi, Opetusministeriön työryhmämuistioita ja selvityksiä 52, 2007, p. 16. This also corresponds to the economic definition of productivity.23x S. C. Ray, Data Envelopment Analysis: Theory and Techniques for Economics and Operations Research, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 275. Thus, in this case, expenditures indicate inputs and the number of pupils and teaching hours outputs. If the PARAS mergers have enhanced productivity, the municipalities would have been able to produce teaching services for pupils at lower expenditures than if the mergers had never occurred.24x Note that in this study, productivity is based on indicators that measure the amounts, not the quality, of services. Teaching hours indicate the amounts of lessons and number of pupils work as a proxy for aggregated output (see J. Drew, M.A. Kortt & B. Dollery, ‘Economies of Scale and Local Government Expenditure: Evidence from Australia’, Administration and Society, Vol. 46, No. 6, 2014, p. 636). Thus, it is possible that the potential decrease in expenditures would be due to the reduction in the quality of services instead of scale economies caused by the mergers (Reingewertz, 2012, p. 246). -

C Previous Merger Literature

Although the governments in several countries have taken actions to enlarge local government units, the benefits from bigger units, according to the prior theoretical and empirical economic research, are far from obvious. Based on economic theories, a larger municipal size can entail economies of scale, in which case the increase in population decreases expenditures per capita. On the other hand, a too large municipal size can cause diseconomies of scale, because of problems in the management and coordination of production processes. Furthermore, as the municipal size increases, population heterogeneity increases as well. As heterogeneity increases, it is more difficult to adjust the service production to the demands of diverse taxpayers and their preferences. Thus, a larger municipal size can increase expenditures due to both diseconomies of scale and preference heterogeneity. The relationship between expenditures and population can be depicted as a U-shaped curve, wherein there first exist positive scale effects as larger municipalities can produce services with lower per capita expenditures than small municipalities. After a certain point (which is the optimal municipal size in terms of expenditures), diseconomies of scale and heterogeneity outweigh the benefits, resulting in an increase in per capita expenditures.25x A. Alesina & R. Baqir & C. Hoxby, ‘Political Jurisdictions in Heterogeneous Communities’, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 112, No. 2, 2004, pp. 348-396; A. Alesina & E. Spolaore, ‘On the Number and Size of Nations’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 112, No. 4, 1997, pp. 1024-1056; Blom-Hansen et al., 2014, p. 791; C.V. Brown & P.M. Jackson, Public Sector Economics, 4th ed., Basil Blackwell, 1990, p. 260; Cobban 2019, p. 466; B. Dollery, J. Byrnes & L. Crase, ‘Australian Local Government Amalgamation: A Conceptual Analysis Population Size and Scale Economies in Municipal Service Provision’, Australian Journal of Regional Studies, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2008, pp. 169-170; T. Saarimaa & J. Tukiainen, ‘Do Voters Value Local Representation? Strategic Voting after Municipal Mergers’, in A. Moisio (Ed.), Rethinking Local Government: Essays on Municipal Reform, Government Institute for Economic Research, 2012, pp. 131-132; R. Steiner & C. Kaiser, ‘Effects of Amalgamations: Evidence from Swiss Municipalities’, Public Management Review, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2017, pp. 235-236.

Municipal size can be increased and the possible economies of scale obtained by municipal mergers. According to the results of previous empirical studies, one should be cautious about the potential benefits of the mergers’ expenditure-moderating effects. Summarizing the results obtained by Moisio and Uusitalo (2013) and Harjunen et al. (2021) in their studies on Finnish municipal mergers, expenditure savings have been present only in administrative expenditures, which account for a minor share of total expenditures.26x O. Harjunen, T. Saarimaa & J. Tukiainen, ‘Political Representation and Effects of Municipal Mergers’, Political Science Research and Methods, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2021, pp. 72-88; A. Moisio & R. Uusitalo, ‘The Impact of Municipal Mergers on Local Public Expenditures in Finland’, Public Finance and Management, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2013, pp. 148-166. Furthermore, a few other results, namely from Canada, Denmark, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands and Poland, back this conclusion.27x Allers & Geertsema, 2016; Blesse & Baskaran, 2016; Blom-Hansen et al., 2014; J. Blom-Hansen, K. Houlberg, S. Serritzlew & D. Treisman, ‘Jurisdiction Size and Local Government Policy Expenditure: Assessing the Effect of Municipal Amalgamation’, American Political Science Review, Vol. 110, No. 4, 2016, pp. 812-831; Cobban, 2019; D. McQuestin, J. Drew & B. Dollery, ‘Do Municipal Mergers Improve Technical Efficiency? An Empirical Analysis of the 2008 Queensland Municipal Merger Program’, Australian Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 77, No. 3, 2017, pp. 442-455; T. Miyazaki, ‘Examining the Relationship between Municipal Consolidation and Cost Reduction: An Instrumental Variable Approach’, Applied Economics, Vol. 50, No. 10, 2018, pp. 1108-1121; P. Swianiewicz & J. Łukomska, ‘Is Small Beautiful? The Quasi-experimental Analysis of the Impact of Territorial Fragmentation on Costs in Polish Local Governments’, Urban Affairs Review, Vol. 55, No. 3, 2019, pp. 832-855. See also Tavares (2018) for a review. On the other hand, according to Reingewertz (2012) and Hanes (2015), economies of scale were obtained in the Israeli reform, in 2003, and in the Swedish reform, in 1952.28x N. Hanes, ‘Amalgamation Impacts on Local Public Expenditures in Sweden’, Local Government Studies, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2015, pp. 63-77. However, in the Swedish reform, the mergers reduced expenditures for mergers of small municipalities, and Hanes (2015) concludes that the mergers may realize economies of scale as long as the municipal population does not exceed ‘some critical size’.

In regard to impacts on business activities, there is a clear shortage of research and scientific knowledge. However, there are a few studies that have considered merger impacts on population growth and on functional development within the merger coalitions. Hanes and Wickström (2008) and Kauder (2016) have studied the impacts of mergers on population growth in Sweden and Germany.29x N. Hanes & M. Wikström, ‘Does the Local Government Structure Affect Population and Income Growth? An Empirical Analysis of the 1952 Municipal Reform in Sweden’, Regional Studies, Vol. 42, No. 4, 2008, pp. 593-604; B. Kauder, ‘Incorporation of Municipalities and Population Growth: A Propensity Score Matching Approach’, Papers in Regional Science, Vol. 95, No. 3, 2016, pp. 539-554. According to the results, the mergers seemed to have a positive impact on population growth in integrated municipalities, which had a low population level. Furthermore, Harjunen et al. (2021) found that the municipalities that gained a weak representation in the post-merger council received a substantial reduction in the local public sector jobs in administration and social and healthcare, compared with municipalities in the same merger, which received a strong representation. However, in the schooling sector and for private-sector jobs similar job mobility was not found. In addition, according to the results of Egger et al. (2022) of German municipal mergers, ‘economic activity’ (measured with geo-coded night-light data) increased in municipalities where the new administrative centre was located and decreased in the municipalities which lost an administrative centre.30x P.H. Egger, M. Koethenbuerger & G. Loumeau, ‘Local Border Reforms and Economic Activity’, Journal of Economic Geography, Vol. 22, 2022, pp. 81-102. Egger et al. (2022) also state that the net effect between the gains and losses was positive.

The results of previous empirical studies can be summarized as follows. First, with few exceptions and the savings in administrative expenditures, there is no evidence of the expenditure-moderating impacts of municipal mergers. Second, there is some evidence of positive population growth impacts for small integrated municipalities and concentric mobility of activities and certain public sector services within the merged coalitions. This study extends existing knowledge on economic impacts by delving deeper into one municipal service sector, comprehensive schooling, and by producing novel information about business impacts. In regard to comprehensive schooling, existing knowledge is very limited. The schooling sector is included, among other municipal sectors, in Moisio and Uusitalo (2013), who studied the impacts of Finnish municipal mergers that took place in the 1970s, and in Roesel (2017), who studied the effects of mergers of larger, county-sized, local governments in the German state of Saxony.31x F. Roesel, ‘Do Mergers of Large Local Governments Reduce Expenditures? – Evidence from Germany Using the Synthetic Control Method’, European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 50, 2017, pp. 22-36. In Moisio and Uusitalo (2013) and Roesel (2017), the impacts of schooling were studied on a general level, as the expenditures per capita. Neither of the studies found evidence of the scale effects on schooling.32x Ibid., did not find scale effects for total expenditures, administration and social care either.

There is also very limited knowledge of business activities. Hanes and Wickström (2008) and Kauder (2016) studied the impacts of mergers on population growth and Egger et al. (2022) on economic activities by using night-light data. For Finnish mergers, Harjunen et al. (2021) touched on the change in private-sector jobs within the merger coalitions. In addition to the effects on population growth, this study uses the number of private-sector jobs and businesses as outcome variables. The perspective is not on the mobility of those variables within the merged coalitions but on examining whether municipal mergers have had an impact on vitality at the level of the entire new coalition. In other words, is the coalition of municipalities better off compared with the situation where the coalition had never accomplished a merger. Furthermore, the selection of control variables in the empirical analysis has been conducted by selecting variables that are directly connected to business activities and comprehensive schooling, instead of using controls on a more general level. -

D Methods

The main difficulty in ex post impact assessment and therefore in measuring the causal effects of regulation is to analyse what would have happened without the regulatory actions.33x R.W. Hahn & J.A. Hird, ‘The Costs and Benefits of Regulation: Review and Synthesis’, Yale Journal of Regulation, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1991, p. 237. In the context of this study, regulatory actions (spurring mergers) led to several municipal mergers. The mergers can be considered to be a treatment to which the merged municipalities were exposed. Thus, it is essential to analyse what the merger municipalities’ development would have been without the treatment. Naturally, this kind of set-up is never available, so there is a missing data problem.34x P.R. Rosenbaum & D.B. Rubin, ‘The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects’, Biometrika, Vol. 70, No. 1, 1983, p. 41. However, the impact of the treatment can be estimated by controlling all other factors that have an impact on the outcome variables (business activities, expenditures and productivity). Because most Finnish municipalities did not implement mergers during the PARAS reform, a DiD analysis35x See J.D. Angrist & J-S. Pischke, Mostly Harmless Econometrics. An Empiricists Companion, Princeton University Press, 2009, pp. 227-243; R. Blundell & M. Costa Dias, ‘Evaluation Methods for Non-Experimental Data’, Fiscal Studies, Vol. 21, No. 4, 2000, pp. 442-444; S.R. Khandker, G.B. Koolwal & H.A. Samad, Handbook on Impact Evaluation: Quantitative Methods and Practices, The World Bank, 2010, pp. 71-78; P.J. McEwan, ‘Empirical Research Methods in the Economics of Education’, in P. Peterson, E. Baker & B. McGaw (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Education, 3rd ed., 2010, pp. 190-191. can be used to estimate the causal effect of the mergers. Thus, the development of a treatment group (merger municipalities) is compared with municipalities in which mergers have not taken a place (a control group).

The next question is, how should a proper control group be selected? In this case, random assignment is not feasible because the merger decisions have not been made by drawing. Under these circumstances, the most straightforward way would be to compare merger municipalities with all other municipalities. The feasibility of this comparison would require the selection of the treatment group not to be correlated with the factors that influence the development of the outcome variables. In other words, if the factors that have an influence on the outcome variables have also influenced merger decisions, there is a systematic difference between the treatment and the control groups. In that case, the straightforward comparison between the merger municipalities and all other municipalities would end up with biased results. That is because the merger municipalities would be, on average, different from other municipalities already before the mergers, and that is why the business activities, expenditures and productivity could be assumed to develop differently even without the mergers.36x Blom-Hansen et al., 2016, p. 812; Moisio & Uusitalo, 2013; Reingewertz, 2012, p. 243; Rosenbaum & Rubin 1983, p. 42.

To test the difference between the merger municipalities and all other municipalities, data was collected a year before the first PARAS mergers (the year 2006).37x The data was collected mostly from the databases maintained by Statistics Finland. In addition, the databases from Education Statistics Finland, Finlex Data Bank and National Land Survey of Finland were used. The distance to the nearest regional centre was calculated using the ArcGIS program by ESRI. Thanks are due to MPhil Simo Rautiainen for calculating the distances. The data was collected from the variables that have been found to explain the location decisions of business activities and the expenditure growth and productivity of comprehensive schooling.38x See, e.g., J. Aaltonen & T. Kirjavainen & A. Moisio, Efficiency and Productivity in Finnish Comprehensive Schooling 1998-2004, VATT Research Reports 127, Government Institute for Economic Research, 2006; M.V. Brown & D.M. Scott, ‘Human Capital Location Choice: Accounting for Amenities and Thick Labor Markets’, Journal of Regional Science, Vol. 52, No. 5, 2012, pp. 787-808; J.B. Cullen & S.D. Levitt, ‘Crime, Urban Flight, and the Consequences for Cities’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 81, No. 2, 1999, pp. 159-169; E.L. Glaeser & J.M. Shapiro, ‘Urban Growth in the 1990s: Is City Living Back?’, Journal of Regional Science, Vol. 43, No. 1, 2003, pp. 139-165; J. Ristilä, Studies on the Spatial Concentration of Human Capital, Jyväskylä Studies in Business and Economics 7, University of Jyväskylä, 2001; H. Tervo, ‘Migration and Labour Market Adjustment: Empirical Evidence from Finland 1985-90’, International Review of Applied Economics, Vol. 14, No. 3, 2000, pp. 343-360; N. Vartiainen, ‘Tarkoittaako suurempi asukasluku pienempiä kustannuksia? Paneeliregressio Suomen kunnista vuosilta 2015-2017’, Kansantaloudellinen aikakauskirja, Vol. 115, No. 3, 2019, pp. 520-541. The results are presented for business activities in Table 1 and for comprehensive schooling in Table 2.

In Tables 1 and 2, let us first focus on the columns ‘Before PSM’. In these columns, the sub-column ‘Difference’ indicates the difference between the averages of merger municipalities (Treatment group) and all other Finnish municipalities (Control group).39x Excluding the autonomous region of Åland. All municipalities involved in mergers in the 2000s and 2010s were also excluded so as not to disturb the results (except for the municipalities in the treatment group). Note that for comprehensive schooling (Table 2) all municipalities in the Helsinki metropolitan area and in the Lapland region and all regional centre cities were excluded based on the propensity score distributions estimated at a later stage of the analysis. That is why the number of observations is lower for comprehensive schooling. Note also that the number of treatment group observations is lower than 68, which was the total number of mergers during the PARAS reform. In some cases, the mergers were ‘chained’ for different years. For example, some municipality might have implemented a merger in 2009 and 2013. In those cases, the merger was considered to be implemented in 2009, being aware that the observation would not receive a ‘full treatment’ until 2013. As Tables 1 and 2 show, there were significant differences between the groups before the mergers took place. The merger municipalities were better off compared with the other municipalities and had, on average, a higher population level, and the population was higher educated and less agricultural. Furthermore, the population level and the number of private-sector jobs developed more positively, there was less unemployment, and the wage level in manufacturing and average selling prices of detached houses were higher. There was also evidence of a better socio-economic status of the merger municipalities. Moreover, the merger municipalities were located closer to the regional centres, indicating the vicinity of the markets and services. Further, the expenditures per pupil and per teaching hours were lower in the merged municipalities. Based on the foregoing findings, there was strong evidence of systematic differences between the merger municipalities and all other municipalities before the mergers took place.Table 1 Pre-treatment Data of Variables Affecting Business Activities40x N. Vartiainen, ‘Kuntaliitosten elinkeinovaikutukset – Seurantatutkimus PARAS-hankkeen kuntaliitoksista’, Focus Localis, Vol. 46, No. 4, 2018, p. 21.Before PSM After PSM PSM improvement Treatment group Control group Difference Treatment group Control group Difference N 50 228 48 48 Population 31097

(32494)13828

(45515)17268*** 30303

(32840)26001

(14873)4301 12967 Population change 2005-2006 (%) 0,09

(1,00)−0,37

(1,48)0,45*** 0,09

(1,01)0,03

(0,71)0,05 0,40 Unemployment (%) 9,7

(3,3)11,1

(4,6)−1,4** 9,6

(3,2)10,4

(2,2)−0,8 0,6 Change in the number of jobs 2005-2006 (%) 2,80

(2,57)1,55

(4,06)1,25*** 2,78

(2,59)2,48

(2,34)0,30 0,95 Change in the number of businesses 2005-2006 (%) 4,01

(2,39)3,41

(3,08)0,60 4,04

(2,43)3,26

(1,06)0,78** −0,18 Residents in urban areas (%) 37,4

(41,0)20,0

(36,4)17,5*** 35,2

(40,3)43,0

(25,1)−7,8 9,7 Agricultural and forestry jobs (%) 7,9

(6,0)14,3

(8,8)−6,4*** 8,2

(6,0)8,0

(3,6)0,2 6,2 Population density (pop/km2) 33,0

(37,2)63,3

(257,1)−30,3* 30,4

(32,0)45,2

(46,5)−14,8* 15,5 Distance to the nearest regional centre (km) 39,9

(30,3)67,7

(49,0)−27,7*** 41,6

(29,8)43,6

(15,3)−2,0 25,7 Average selling price of detached houses (€) 119178

(36013)106130

(73633)13048* 118845

(36686)124593

(23692)−5748 7300 Income tax rate 18,75

(0,77)18,93

(0,61)−0,19 18,73

(0,79)18,91

(0,29)−0,18 0,01 Crimes per 1000 inhabitants 132

(37)128

(60)4 132

(38)131

(22)1 3 Births per 1000 inhabitants 10,7

(2,0)9,4

(3,2)1,3*** 10,6

(2,0)10,4

(1,6)0,2 1,1 Election turnout (%) 70,5

(3,7)69,3

(4,6)1,2** 70,6

(3,7)70,7

(1,8)−0,1 1,1 High education (%) 4,65

(2,18)3,65

(2,86)1,00*** 4,56

(2,16)4,49

(1,03)0,07 0,93 Senior Secondary School (%) 96

(20)75

(43)21*** 96

(20)95

(12)1 20 Average salary in manufacturing (€) 32350

(4412)28894

(4987)3456*** 32147

(4371)31504

(2420)642 2814 Standard deviations in parentheses below the average values.

* Statistically significant at 10 percent level

** Statistically significant at 5 percent level

*** Statistically significant at 1 percent levelTable 2 Pre-treatment Data of Variables Affecting Expenditure Growth and Productivity of Comprehensive Schooling41x N. Vartiainen, ‘Onko PARAS-hankkeen tavoitteet saavutettu kuntien perusopetustoimessa? Tutkimus kuntaliitosten meno- ja tuottavuusvaikutuksista’, Focus Localis, Vol. 49, No. 1, 2021b, p. 48.Before PSM After PSM PSM improvement Treatment group Control group Difference Treatment group Control group Difference N 40 194 40 40 Land area (km) 951

(511)683

(815)267*** 951

(511)826

(388)125 142 Distance to the nearest regional centre (km) 50,9

(24,1)60,3

(30,8)−9,3** 50,9

(24,1)59,2

(33,1)−8,3 1 Population change 2005-2006 (%) −0,00

(1,06)−0,30

(1,52)0,30 −0,00

(1,06)0,24

(1,93)−0,24 0,06 Unemployment (%) 9,1

(3,3)10,5

(4,3)−1,4** 9,1

(3,3)10,1

(2,9)−1,0 0,4 High education (%) 4,0

(1,8)3,4

(1,9)0,6* 4,0

(1,8)4,2

(2,6)−0,2 0,4 Number of pupils 1974

(1249)964

(1084)1011*** 1974

(1249)1873

(1625)101 910 Average school size (pupils) 138

(49)119

(61)19* 138

(49)144

(54)−6 13 Expenditures per student (€) 6341

(657)6727

(915)−385*** 6341

(657)6287

(672)54 331 Expenditures per teaching hour (€) 89,8

(5,8)92,2

(8,1)−2,4** 89,8

(5,8)92,0

(6,7)−2,3 0,1 Share of pupils in special education (%) 7,6

(1,8)7,1

(2.6)0,5 7,6

(1,8)7,1

(2,0)0,5 0 Multilingual teaching (%) 17,5 10,3 7,2 17,5 20,0 −2,5 4,7 Senior secondary school (%) 100 94,3 5,7 100 100 0 5,7 Standard deviations in parentheses below the average values.

* Statistically significant at 10 percent level

** Statistically significant at 5 percent level

*** Statistically significant at 1 percent levelThe systematic differences between the groups can be controlled by matching every merged municipality to a similar counterpart, where a merger had not taken place. The matching was conducted by using ‘propensity score matching’ (PSM),42x Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983. which has also been used in a municipal merger context by Kauder (2016) and Moisio and Uusitalo (2013). A propensity score is the probability of assignment to a treatment, which means in this case a probability to accomplish a municipal merger. Merger probabilities were estimated by using logistic regressions, in which merger decisions were explained by the variables presented in Tables 1 and 2. The logit estimations were conducted separately for business activities and for comprehensive schooling. Thus, the merger decisions were explained by the variables presented in Table 1 for business activities and by the variables presented in Table 2 for comprehensive schooling. The estimations were based on the data from 2006, which was the year right before the first mergers of the PARAS reform took place.

To create the matched control group, every municipal pair in Finland was scanned.43x Except municipalities in the Åland region and the municipalities that were involved in mergers in the 2000s and 2010s (except for the PARAS mergers). Thus, instead of just one municipality, every merger coalition was compared with a municipal pair, which would potentially have accomplished a merger. The potential ‘couple’ had to locate in the same region and have a common border either by land or by sea. To be more specific, all municipal pairs were divided based on population. Each observation in the logit estimations included separate variables for larger and smaller municipalities. Thus, the matching was conducted by finding a counterpart for every merger coalition, in which the larger municipality would be as similar as possible to the larger municipality in the counterpart and the smaller municipality as similar as possible to the smaller municipality in the counterpart. However, it should be noted that about half of the mergers were ‘multi-municipal mergers’, meaning that there were more than two municipalities involved in a coalition, even up to ten municipalities. In those cases, the counterpart was matched based on the variables of the two most highly populated municipalities in a merger coalition, just as the ‘problem’ was solved in Moisio and Uusitalo (2003).44x A. Moisio & R. Uusitalo, Kuntien yhdistymisten vaikutukset kuntien menoihin, Sisäasiainministeriö, Kuntaosaston julkaisu 4, 2003.

As a result of the logit estimations, the matching was based on the following variables for business activities: population level, population change, change in the number of private-sector jobs, the share of agricultural and forestry jobs, the distance to the nearest regional centre, birth rate, and whether the municipality had its own high school. For comprehensive schooling, the matching was based on the number of pupils, average school size, land area, population change, unemployment rate, and whether the municipality offered multilingual teaching.45x The logit estimation tables are not presented here in order to save space. The tables are available from the author on request.

If the matching has been successful, there should not be any substantial differences between the treatment and control groups before the mergers. To verify the similarity, let us look at Tables 1 and 2 once again and now concentrate on the columns ‘After PSM’ and ‘PSM improvement’. The former indicates the differences between merged municipalities and matched control groups. The latter indicates how much the average differences between the groups have decreased owing to the PSM procedure.46x Note that after the PSM procedure, two observations were dropped from the original treatment group observations for business activities. Based on the propensity scores, there were no counterparts similar enough for those mergers. According to the results, the matching distinctly removed the differences between the groups compared with the prior comparison. The difference between the groups increased only for one variable (change in the number of businesses). For all the other 28 variables, the differences reduced substantially, or at least stood still. After the matching, there are no statistically significant differences between the groups, except for the change in the number of businesses (significant at the five percent level) and population density (significant at the ten percent level). -

E Results

I Business Activities

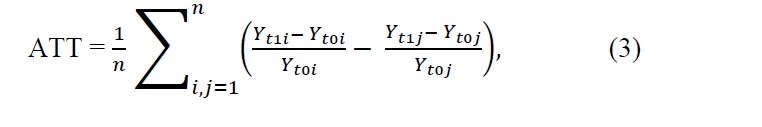

The development of business activities was analysed based on three indicators: population change, the change in private-sector jobs, and the change in the number of businesses.47x The data was collected from the databases maintained by Statistics Finland. The treatment group consisted of 48 merger municipalities, which accomplished a merger between the years 2007 and 2013. The purpose of the analysis is to estimate the Average Treatment Effect of the Treated (ATT). The statistical analysis was based on an average annual change of the aforementioned three variables in a certain period:

where ‘Y’ is an outcome variable (population, private-sector jobs or businesses), ‘1’ indicates the latter time point, ‘0’ former time point, ‘i’ observations in the treatment group, ‘j’ observations in the control group, and ‘t’ the number of years in a period under analysis.

Expressed verbally, ATT is defined by calculating an average annual change in the growth of the variable Y for each merger-municipality, subtracting the matched counterparts’ corresponding growth, and, finally, calculating the average of all the differences between the merger municipalities and their counterparts. In other words, ATT is a DiD estimator, which is an average of the differences between every 48 merger municipalities and their counterpart’s average annual changes. In fact, for business activities, every merged municipality was compared, instead of just one municipal pair, with an average of three municipal pairs. Hence, the matching was conducted by ‘three nearest neighbour matching’. The advantage of using three nearest neighbours is that the analysis is not that sensitive to possible outliers.48x See, e.g., Kauder (2016, pp. 551-552) for different matching methods. On the other hand, one nearest neighbour matching would be preferable, if there is a large enough difference in the propensity scores between the treatment group observations and the second and third nearest neighbours. For business activities, the possible bias from the three nearest neighbours matching was minimized by dropping out counterparts, in which the difference in the propensity scores was at least five percentage points. The matching was also conducted with replacement, which means that the same municipal pair was allowed to be in the control group more than once.

Before reporting the actual results about the impacts of the mergers, the validity of a common trends assumption should be detected.49x See Angrist & Pischke, 2009, pp. 230-233. This can be performed by examining the similarity of the average annual changes between the treatment and control groups before the treatment took place. If the matching has been successful, there should not be any substantial differences in the trends between the groups. According to the findings presented in Table 3, the growth of all indicators was very similar in a two-year period before the accomplishments of the mergers, indicating that the common trends assumption holds. The ATT scores before the implementation of the mergers (ATT before) are very close to zero. The scores were not statistically significant according to paired t-tests. Based on the earlier findings, it can be assumed that the control groups’ growth should correspond quite well with the growth the merger municipalities would have had if the mergers had never taken place.Table 3 Average Treatment Effect of the Treated (ATT) for All Observations50x Vartiainen, 2018, p. 24.Treatment group

(N = 48)Control group

(N = 48)ATT

(N = 48)Before After Before After Before After Population 0,13

(1,00)−0,19

(0,77)0,14

(0,66)−0,12

(0,55)−0,01

(1,08)−0,06

(0,82)Private-sector jobs 0,29

(2,40)−1,73

(1,57)0,22

(1,76)−1,00

(0,70)0,07

(2,34)−0,73***

(1,51)Businesses 3,10

(1,40)1,49

(0,72)3,05

(0,87)1,58

(0,56)0,06

(1,53)−0,10

(0,82)Standard deviations in parentheses below the average values.

* Statistically significant at 10 percent level.

** Statistically significant at 5 percent level.

*** Statistically significant at 1 percent level.If the mergers have had an impact on the development of business activities, there should be differences between the groups after the mergers. To analyse the impact of the mergers, the average annual changes were calculated from the time point at which the mergers were accomplished to the latest possible time point within the scope of available data when the analyses were conducted. For population growth, there was data until the end of 2016, for businesses until the first quarter of 2017, and for private-sector jobs until the end of 2015. According to Table 3 (ATT after), the growth between treatment and control groups was very similar for population change and for the number of businesses. The differences between the groups are not statistically significant for those indicators. However, for the growth of private-sector jobs, there is a statistically significant difference. For the merged municipalities the number of private-sector jobs decreased annually by 1.73 percent on average. The growth was also negative for the control group, but more moderate compared with the merged municipalities. The difference between the groups is 0.73 percentage points and significant at the one percent level. Hence, it seems that municipal mergers have had a negative impact on the development of private-sector jobs.

The analysis presented in Table 3 included all 48 municipalities and their counterparts. Within these 48 observations, there were mergers that consisted of only two municipalities and mergers that consisted of more than two municipalities (even up to ten municipalities). Thus, in addition to the foregoing analysis, the impacts of the mergers were analysed only including those 21 mergers that consisted of two municipalities. Concentrating on those mergers is relevant for three reasons. First, in the analysis presented in Table 3, also the multi-municipal mergers were compared with counterparts, which consisted of municipal pairs. By focusing on mergers that consisted of two municipalities, it could be guaranteed that every merger was compared with a counterpart, which included the same number of municipalities. Second, all observations that ‘chained’ the mergers for different years could be excluded. Some mergers were accomplished in multiple stages in different years. In those cases, the treatment was considered to begin with the first merger. This means that chained mergers did not receive ‘a full treatment’ from the beginning of the merger because other municipalities were merged after that time point. By excluding those mergers, it could be assured that all observations in the treatment group received a full treatment from the beginning. Third, dropping out multi-municipal mergers resulted in dropping out all highly populated municipalities as well. The impacts can be different in the mergers that include ‘a dominant’ municipality with a high population compared with mergers where two relatively low-populated municipalities merge. The exclusion of multi-municipal mergers happened to exclude highly populated municipalities as well, making it possible to analyse the impact of the mergers concentrating on lower-populated municipalities.51x According to the statistics from 2006, the most highly populated municipality in the treatment group without multi-municipal mergers had 30 347 inhabitants (both merger partners combined).Table 4 Average Treatment Effect of the Treated (ATT) for Observations without Multi-municipal Mergers52x Vartiainen, 2018, p. 26.Treatment group (N = 21) Control group (N = 21) ATT (N = 21) Before After Before After Before After Population −0,12

(0,85)−0,47

(0,76)0,07

(0,64)−0,17

(0,57)−0,19

(0,86)−0,29*

(0,76)Private-sector jobs −0,39

(2,91)−1,78

(1,66)0,15

(1,72)−1,02

(0,76)−0,54

(2,37)−0,76**

(1,57)Businesses 2,87

(1,61)1,26

(0,81)2,82

(0,82)1,50

(0,53)0,06

(1,69)−0,24

(0,84)Standard deviations in parentheses below the average values.

* Statistically significant at 10 percent level.

** Statistically significant at 5 percent level.

*** Statistically significant at 1 percent level.According to the results presented in Table 4, it seems that the differences between the groups are somewhat larger before the mergers for population and private-sector jobs, compared with the results with all observations. This happens to be the case especially for private-sector jobs. Although the differences are not statistically significant, the findings might indicate that the matching was not as precise as it was with a larger number of observations. However, there was still no evidence of the mergers’ positive impact on business activities. All ATT values are negative after the mergers and statistically significant for private-sector jobs (at five percent level) and for the population (at ten percent level). The differences between the groups have also increased after the mergers for all variables.

As a robustness check, all the aforementioned tests were also conducted by one nearest neighbour matching. The results were very similar compared with the three nearest neighbours and did not change the interpretations. Furthermore, the impacts of the mergers were tested including only mergers that were accomplished in 2007 (twelve observations). It was thus possible to examine whether the mergers begin to have positive impacts over a longer period. There was no evidence of the benefits of the mergers with this testing either. Overall, there is absolutely no evidence of the positive impacts of the mergers on the location decisions of inhabitants, private-sector jobs and businesses. On the contrary, from the aspect of private-sector jobs, the impact seems to be even negative.II Comprehensive Schooling

For comprehensive schooling, one nearest neighbour matching with replacement was used. Based on the propensity score distribution, it was visible that there were no multiple fitting counterparts for many observations in the treatment group. To improve the similarity of merger observations and their counterparts even further, the propensity scores were eventually estimated by excluding all regional centres, as well as the municipalities in the Helsinki metropolitan area and the sparsely populated Lapland region. Municipalities in the autonomous region of Åland and those that were involved in mergers in this millennium (except for those accomplished during the PARAS reform) were excluded from both analyses (business activities and comprehensive schooling). Dropping out the regional centres means that the number of observations is lower for comprehensive schooling than for business activities.

The growth of expenditures per pupil53x Vartiainen, 2021b, p. 54.

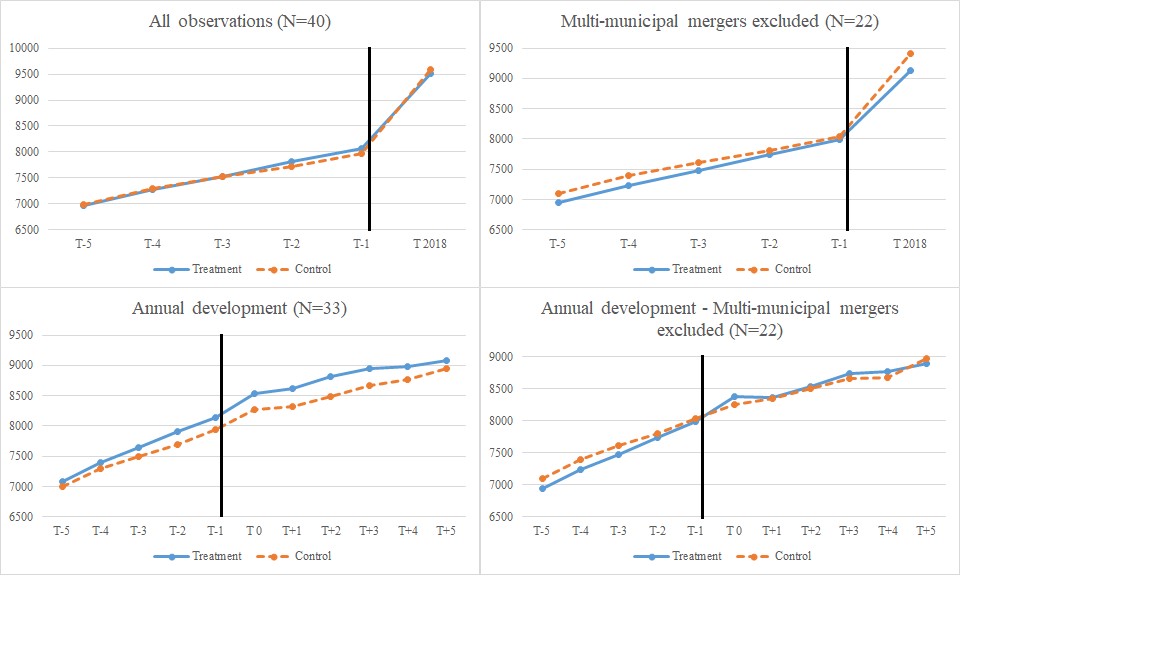

Figure 1 depicts the comparison between the treatment and control groups for expenditures per pupil. Time ‘T’ is presented on the horizontal axis and expenditures per pupil on the vertical axis in 2018 euros. The vertical line indicates the timing of the mergers, which is right after the time spot ‘T–1’.54x The mergers were officially accomplished on the first day of the year ‘T0’, which is practically right after T–1. The expenditure growth for all observations is depicted in the upper left corner of Figure 1 (N = 40). For all observations, only the year 2018 is analysed after the mergers. This is because of the chained mergers. As previously mentioned, some of the merger coalitions chained the mergers for different years, which would make it arguable to define the first year after the merger nominally as T + 1 in the cases in which some more populated municipalities consolidated after that time point. The curves in the lower left corner depict the growth without chained mergers (N = 33), and the curves on the right-hand side the observations without multi-municipal mergers (N = 22).

As Figure 1 shows, there were no substantial differences between the trends. Thus, it seems that municipal mergers have not had any impact on expenditure growth and productivity on a per-pupil basis. The differences between the groups were tested statistically using DiD regressions as well as t-tests for equality of means for each year separately. The DiD regression can be presented as follows:

where ‘Y’ depicts the expenditures per pupil for observations ‘i’. ‘Merger’ is a dummy variable for treatment (1 = merger and 0 = control). ‘Year’ denotes year-dummies starting from five years before the mergers (T–5). Year*Merger is an interaction term, which is the DiD estimator.55x See also Blom-Hansen et al., 2016, pp. 818-819. All regressions were estimated using OLS and clustered standard errors by municipal coalitions. When estimating DiD regressions, the reference year must be chosen with which the change in trends is contrasted. In this study, both T–1 and T–5 were used as reference years. If, for example, in T–1 some deviant variation would occur, using T–1 as a reference year could cause some bias in the results. To ensure the validity of the results, T–5 was also used as a reference year.

In regard to results, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups according to DiD regressions and t-tests. On this basis, two conclusions can be drawn. First, there was no statistical evidence of the violation of the common trends assumption, which indicates the success of the PSM procedure. Second, there was no statistical evidence of any impacts of municipal mergers on the growth of expenditures per pupil.

All the analyses were also conducted including only mergers implemented between 2007 and 2009. In those cases, the annual observations were possible to be extended to ten years after the mergers.56x Long-term examination is particularly important in the Finnish case, because of the statutory five-year protection against dismissal. To spur on mergers during the PARAS reform, the Finnish legislature provided protection for municipal employees from losing their jobs for economic and production reasons for five years after the mergers. Hence, it could have been possible that the municipalities were unable to adjust their service production entirely during that five-year period. However, it should be noted that Saarimaa et al. (2016) found that the expirations of the five-year protections did not result in any significant dismissals (T. Saarimaa, A. Saastamoinen, T. Suhonen, L. Tervonen, J. Tukiainen & H. Vartiainen, Kuntien sääntelyn periaatteet, Valtioneuvoston selvitys- ja tutkimustoiminnan julkaisusarja 21, 2016). The interpretations did not change with these testings either, which means that there were no signs of the impacts of the mergers even in the longer term. Those figures and all DiD regression and t-test tables are not presented in this article in order to save space but are available from the author on request.

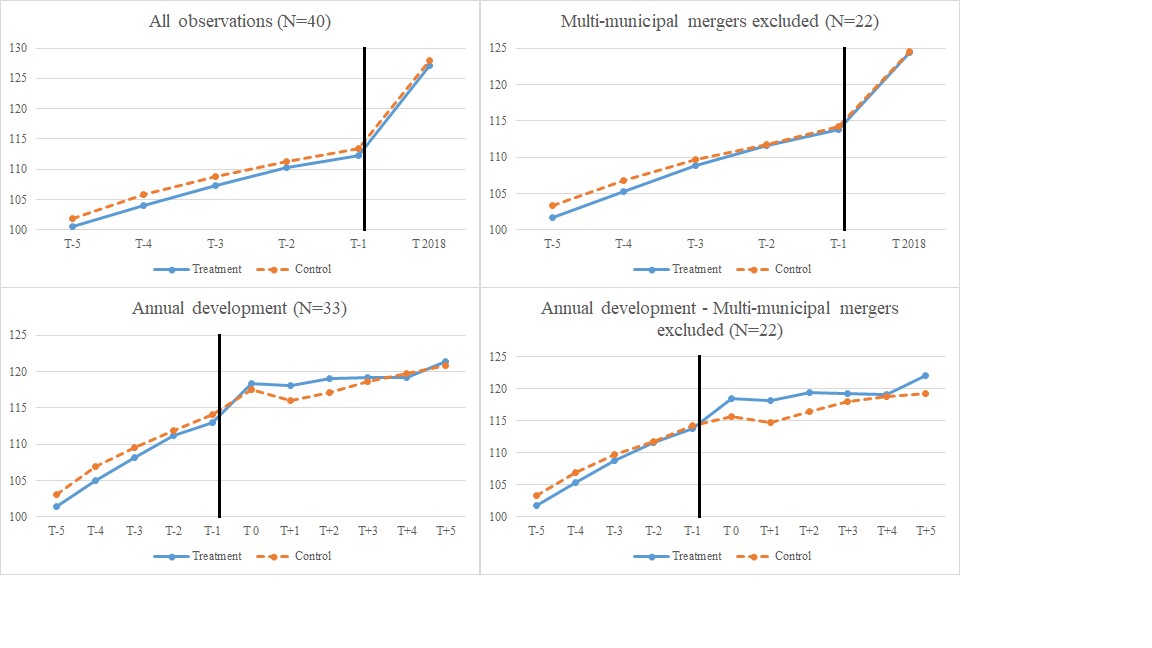

Although the mergers had no impact on expenditures per pupil, it is possible that the merger municipalities could have been able to produce more teaching hours for their students. Figure 2 presents the results for the expenditures per teaching hour.The growth of expenditures per teaching hour57x Vartiainen, 2021b, p. 59.

The analysis with the inclusion of all observations (upper left corner) indicates that the expenditures per teaching hour were slightly lower for the treatment group both before and after the mergers, and there is no change in the trend after the mergers. According to the annual analysis, the expenditures seem to rise just after the mergers for merger municipalities. The DiD regressions indicate that one year after the mergers there was a statistically significant difference between the groups for both including (lower left corner) and excluding multi-municipal mergers (lower right corner). However, the differences were significant just at a ten percent level. Hence, there was no evidence of the impacts of municipal mergers on expenditures per teaching hour either. This conclusion does not change when the impacts are analysed just for mergers implemented between 2007 and 2009.

Altogether, there was no evidence of any expenditure-moderating or productivity-enhancing impacts of Finnish municipal mergers on comprehensive schooling. Now the question is, what might explain the results? As Harjunen et al. (2017) have stated, the only way to achieve scale economies might be to increase facility size (schools in this case).58x O. Harjunen, T. Saarimaa & J. Tukiainen, Political Representation and Effects of Municipal Mergers, VATT Working Papers 98, Government Institute for Economic Research, 2017, p. 27. In fact, Aaltonen et al. (2006) found evidence of the positive association between school size and productivity in Finnish comprehensive schooling.59x It should be noted that in Aaltonen et al. (2006), productivity was measured using the number of pupils, grade point averages and the number of pupils admitted to upper secondary education as output variables. Hence, it is relevant to analyse whether there are differences between the treatment and the control groups in increasing school size. The size increase can be detected, for example, by analysing the reduction in the number of schools. If the municipalities disband schools, it indicates that they are centralizing school structures. The analysis was conducted as follows:

where ‘Y’ is the number of comprehensive schools in municipalities ‘i’ and ‘j’.

The results are presented in Table 5. Column ‘ATT before’ indicates the average difference between the groups in the percentage change in the number of schools over a four-year period before the mergers. ‘ATT after’ indicates the corresponding difference after the mergers until 2018. It is notable that all values are negative before and after the mergers for both groups. This indicates that for both the treatment and the control groups the number of schools has been decreasing throughout the examination period. There were no substantial differences between the groups before and after the mergers, but it seems that for merger municipalities, the school closings have been slightly more moderate. According to t-tests, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups, except for the analysis including all observations, which is significant at a ten percent level. It can be summarized that the mergers have not enhanced school closings. This result might well explain why the mergers have had no expenditure-moderating or productivity-enhancing impacts on comprehensive schooling.

Table 5 The Change in the Number of Schools.60x Vartiainen, 2021b, p. 63.Treatment group Control group ATT Before After Before After Before After All observations (N = 40) −11,5

(10,7)−23,6

(17,3)−13,0

(16,2)−30,3

(16,0)1,5

(20,0)6,7*

(23,2)Multi-municipal mergers excluded

(N = 22)−14,1

(10,6)−23,3

(19,7)−11,2

(14,7)−29,0

(15,0)−2,9

(19,3)5,8

(26,2)Mergers accomplished between 2007 and 2009 (N = 32) −11,4

(11,1)−25,6

(17,7)−13,0

(17,3)−31,8

(14,9)1,7

(21,3)6,2

(22,9)Mergers accomplished between 2007 and 2009 – Multi-municipal mergers excluded (N = 15) −15,5

(10,9)−26,3

(21,5)−11,8

(16,8)−30,1

(12,7)−3,7

(21,6)3,8

(26,3)Standard deviations in parentheses below the average values.

* Statistically significant at 10 percent level.

** Statistically significant at 5 percent level.

*** Statistically significant at 1 percent level.The results are presented in Table 5. Column ‘ATT before’ indicates the average difference between the groups in the percentage change in the number of schools over a four-year period before the mergers. ‘ATT after’ indicates the corresponding difference after the mergers until 2018. It is notable that all values are negative before and after the mergers for both groups. This indicates that for both the treatment and the control groups the number of schools has been decreasing throughout the examination period. There were no substantial differences between the groups before and after the mergers, but it seems that for merger municipalities, the school closings have been slightly more moderate. According to t-tests, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups, except for the analysis including all observations, which is significant at a ten percent level. It can be summarized that the mergers have not enhanced school closings. This result might well explain why the mergers have had no expenditure-moderating or productivity-enhancing impacts on comprehensive schooling.

-

F Conclusion

In this article, an ex post evaluation of the impacts of Finnish municipal structure regulation was presented. The impact assessment was based on the objectives set by the Finnish legislature for the so-called PARAS reform. Thus, municipal mergers’ productivity-enhancing, expenditure-moderating and vitality effects were analysed. The productivity and expenditure effects were studied for comprehensive schooling, and vitality was measured as the impacts on business activities. The purpose of the ex post analysis was to produce scientific evidence to support future ex ante evaluations on municipal structures.

The results can be summarized as follows: First, municipal mergers have not had any positive impacts on business activities. Thus, the removal of municipal borders has not turned municipalities more attractive for residents and businesses and enhanced vitality in this manner. It still might be possible that the mergers create some improvement potential for municipalities, for example in the form of more functional enterprise and industrial policy. In that case, the municipalities have not been able to exploit that potential. Second, the mergers have had no effects on expenditure growth and productivity in comprehensive schooling. These sector-specific results are backed by the previous research about the impacts at a more general level, and the results underpin the findings that municipal mergers have no impact on local government expenditures (except for administrative expenditures). Hence, it can be stated that if the regulator seeks to moderate the expenditure growth of the municipal sector, municipal mergers is not a proper regulatory alternative.

It should be noted that in this study the impacts of the mergers were analysed on average, including all kinds of mergers. It would be useful to analyse the impacts for different types of mergers too. This type of evidence could be used to provide the regulator with additional evidence on whether it is reasonable to spur municipalities to form certain kinds of merger coalitions. Another aspect is the length of the monitoring period. In this study, the impacts were analysed for a maximum of ten years after the mergers. It is somewhat possible that the restructuring of enterprise and industrial policy requires a longer period to reach its full potential. Subsequently, it would be useful to obtain research data in the longer term as well. With regard to impacts on comprehensive schooling, it is even less likely to expect any expenditure-moderating impacts even in a longer period. The mergers have had no impact on the school closings, and, thus, the potential for savings is limited in both the short and the long term.

Overall, the PARAS reform did not achieve its regulatory objectives based on the indicators used in this study. One explanation might be in the deficient ex ante evaluations. Extensive reforms (such as PARAS) should be based on a thorough ex ante evaluation of different regulatory alternatives and on evidence-based decision-making. One way to strengthen the evidence base for ex ante assessments and decision-making processes is to systematically carry out ex post evaluations. This article will, hopefully, make its own contribution to the future legislative drafting processes.

Noten

-

1 See, e.g., European Court of Auditors, Ex-post Review of EU Legislation: A Well-established System, But Incomplete, Special Report 16, 2018; OECD, Regulatory Impact Assessment, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, 2020.

-

2 L. Mergaert & R. Minto, ‘Ex Ante and Ex Post Evaluations: Two Sides of the Same Coin. The Case of Gender Mainstreaming in EU Research Policy’, European Journal of Risk Regulation, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2015, pp. 48-49; C.V. Patton & D.S. Sawicki, Basic Methods of Policy Analysis and Planning, 2nd ed., Prentice Hall, 1993, p. 46-52, 63; P. Popelier & V. Verlinden, ‘The Context of the Rise of Ex Ante Evaluation’, in J. Verschuure (Ed.), The Impact of Legislation. A Critical Analysis of Ex Ante Evaluation, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2009, p. 18; J.A. Schwartz, ‘Approaches to Cost-benefit Analysis’, in C.A. Dunlop & C.M. Radaelli (Eds.), Handbook of Regulatory Impact Assessment, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2016, pp. 35-41; K. van Aeken, ‘From Vision to Reality: Ex Post Evaluation of Legislation’, Legisprudence, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2011, pp. 45, 51; H. Wollman, ‘Policy Evaluation and Evaluation Research’, in F. Fischer & G.J. Miller & M.S. Sidney (Eds.), Handbook of Public Policy Analysis. Theory, Politics, and Methods, CRC Press, 2007, p. 393.

-

3 A.F. Tavares, ‘Municipal Amalgamations and Their Effects: A Literature Review’, Miscellanea Geographica – Regional Studies on Development, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2018, p. 5.

-

4 V. Vihriälä, ‘Politiikka-analyysi (talous)politiikassa’, in S. Ilmakunnas & T. Junka & R. Uusitalo (Eds.), Vaikuttavaa tutkimusta – miten arviointitutkimus palvelee päätöksenteon tarpeita?, VATT-julkaisuja 47, Government Institute for Economic Research, 2008, p. 27.

-

5 A. Valli-Lintu, Sote- ja kuntarakenteen pitkä kujanjuoksu, Kunnallisalan kehittämissäätiön julkaisu 10, 2017, p. 8.

-

6 S. Taekema, ‘Theoretical and Normative Frameworks for Legal Research: Putting Theory into Practice’, Law and Method, 2018, pp. 1-17.

-

7 N. Vartiainen, Suurempi kunta on elinvoimaisempi kunta? Lainsäädännön jälkikäteinen vaikutusarviointi päätöksenteon tukena, Publications of the University of Eastern Finland. Dissertations in Social Sciences and Business Studies 254, 2021a.

-

8 T.W. Cobban, ‘Bigger Is Better: Reducing the Cost of Local Administration by Increasing Jurisdiction Size in Ontario, Canada, 1995-2010’, Urban Affairs Review, Vol. 55, No. 2, 2019, pp. 462-500.

-

9 J. Blom-Hansen, K. Houlberg & S. Serritzlew, ‘Size, Democracy, and the Economic Costs of Running the Political System’, American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 58, No. 4, 2014, pp. 790-803.

-

10 S. Blesse & T. Baskaran, ‘Do Municipal Mergers Reduce Costs? Evidence from a German Federal State’, Regional Science and Urban Economics, Vol. 59, 2016, pp. 54-74.

-

11 Y. Reingewertz, ‘Do Municipal Amalgamations Work? Evidence from Municipalities in Israel’, Journal of Urban Economics, Vol. 72, No. 2-3, 2012, pp. 240-251.

-

12 H. Hirota & H. Yunoue, ‘Evaluation of the Fiscal Effect on Municipal Mergers: Quasi-experimental Evidence from Japanese Municipal Data’, Regional Science and Urban Economics, Vol. 66, 2017, pp. 132-149.

-

13 M.A. Allers & J.B. Geertsema, ‘The Effects of Local Government Amalgamation on Public Spending, Taxation, and Service Levels: Evidence from 15 Years of Municipal Consolidation’, Journal of Regional Science, Vol. 56, No. 4, 2016, pp. 659-682.

-

14 B.T. Hinnerich, ‘Do Merging Local Governments Free Ride on Their Counterparts When Facing Boundary Reform?’, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 93, No. 5-6, 2009, pp. 721-728.

-

15 Government bill 155/2006, Hallituksen esitys Eduskunnalle laiksi kunta- ja palvelurakenneuudistuksesta sekä laeiksi kuntajakolain muuttamisesta ja varainsiirtoverolain muuttamisesta.

-

16 Government bill 31/2013, Hallituksen esitys eduskunnalle laeiksi kuntajakolain muuttamisesta ja väliaikaisesta muuttamisesta, kuntajakolain eräiden säännösten kumoamisesta sekä kielilain muuttamisesta.

-

17 In addition to municipal mergers, the PARAS reform also produced several cooperation districts, especially in the social and healthcare sector. However, the impacts on cooperation districts are not within the scope of this study.

-

18 Government bill 125/2009, Hallituksen esitys Eduskunnalle kuntajakolaiksi, p. 48; Administration Committee report 31/2006, Hallintovaliokunnan mietintö hallituksen esityksestä (HE 155/2006 vp) laiksi kunta- ja palvelurakenneuudistuksesta sekä laeiksi kuntajakolain muuttamisesta ja varainsiirtoverolain muuttamisesta; Finnish Ministry of Finance, Elinvoimainen kunta- ja palvelurakenne. Osa I Selvitysosa, Kunnallishallinnon rakennetyöryhmän selvitys, Valtiovarainministeriön julkaisuja 5a, 2012, pp. 17, 158.

-

19 Finnish Ministry of Finance, 2012, pp. 17, 158.

-

20 Government bill 31/2013.

-

21 A. Koski, A. Kyösti & J. Halonen, Opittavaa kuntaliitosprosesseista. META-arviointitutkimus 2000-luvun kuntaliitosdokumenteista, Suomen Kuntaliitto, 2013, p. 106.

-

22 Finnish Ministry of Education, Koulutuksen seurantaohjelma. Kunta- ja palvelurakenneuudistuksen koulutuspoliittisen arvioinnin sekä eduskunnalle laadittavan koulutuksen arviointikertomuksen tueksi, Opetusministeriön työryhmämuistioita ja selvityksiä 52, 2007, p. 16.

-

23 S. C. Ray, Data Envelopment Analysis: Theory and Techniques for Economics and Operations Research, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 275.

-

24 Note that in this study, productivity is based on indicators that measure the amounts, not the quality, of services. Teaching hours indicate the amounts of lessons and number of pupils work as a proxy for aggregated output (see J. Drew, M.A. Kortt & B. Dollery, ‘Economies of Scale and Local Government Expenditure: Evidence from Australia’, Administration and Society, Vol. 46, No. 6, 2014, p. 636). Thus, it is possible that the potential decrease in expenditures would be due to the reduction in the quality of services instead of scale economies caused by the mergers (Reingewertz, 2012, p. 246).

-

25 A. Alesina & R. Baqir & C. Hoxby, ‘Political Jurisdictions in Heterogeneous Communities’, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 112, No. 2, 2004, pp. 348-396; A. Alesina & E. Spolaore, ‘On the Number and Size of Nations’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 112, No. 4, 1997, pp. 1024-1056; Blom-Hansen et al., 2014, p. 791; C.V. Brown & P.M. Jackson, Public Sector Economics, 4th ed., Basil Blackwell, 1990, p. 260; Cobban 2019, p. 466; B. Dollery, J. Byrnes & L. Crase, ‘Australian Local Government Amalgamation: A Conceptual Analysis Population Size and Scale Economies in Municipal Service Provision’, Australian Journal of Regional Studies, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2008, pp. 169-170; T. Saarimaa & J. Tukiainen, ‘Do Voters Value Local Representation? Strategic Voting after Municipal Mergers’, in A. Moisio (Ed.), Rethinking Local Government: Essays on Municipal Reform, Government Institute for Economic Research, 2012, pp. 131-132; R. Steiner & C. Kaiser, ‘Effects of Amalgamations: Evidence from Swiss Municipalities’, Public Management Review, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2017, pp. 235-236.

-

26 O. Harjunen, T. Saarimaa & J. Tukiainen, ‘Political Representation and Effects of Municipal Mergers’, Political Science Research and Methods, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2021, pp. 72-88; A. Moisio & R. Uusitalo, ‘The Impact of Municipal Mergers on Local Public Expenditures in Finland’, Public Finance and Management, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2013, pp. 148-166.

-

27 Allers & Geertsema, 2016; Blesse & Baskaran, 2016; Blom-Hansen et al., 2014; J. Blom-Hansen, K. Houlberg, S. Serritzlew & D. Treisman, ‘Jurisdiction Size and Local Government Policy Expenditure: Assessing the Effect of Municipal Amalgamation’, American Political Science Review, Vol. 110, No. 4, 2016, pp. 812-831; Cobban, 2019; D. McQuestin, J. Drew & B. Dollery, ‘Do Municipal Mergers Improve Technical Efficiency? An Empirical Analysis of the 2008 Queensland Municipal Merger Program’, Australian Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 77, No. 3, 2017, pp. 442-455; T. Miyazaki, ‘Examining the Relationship between Municipal Consolidation and Cost Reduction: An Instrumental Variable Approach’, Applied Economics, Vol. 50, No. 10, 2018, pp. 1108-1121; P. Swianiewicz & J. Łukomska, ‘Is Small Beautiful? The Quasi-experimental Analysis of the Impact of Territorial Fragmentation on Costs in Polish Local Governments’, Urban Affairs Review, Vol. 55, No. 3, 2019, pp. 832-855. See also Tavares (2018) for a review.

-

28 N. Hanes, ‘Amalgamation Impacts on Local Public Expenditures in Sweden’, Local Government Studies, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2015, pp. 63-77.

-

29 N. Hanes & M. Wikström, ‘Does the Local Government Structure Affect Population and Income Growth? An Empirical Analysis of the 1952 Municipal Reform in Sweden’, Regional Studies, Vol. 42, No. 4, 2008, pp. 593-604; B. Kauder, ‘Incorporation of Municipalities and Population Growth: A Propensity Score Matching Approach’, Papers in Regional Science, Vol. 95, No. 3, 2016, pp. 539-554.

-

30 P.H. Egger, M. Koethenbuerger & G. Loumeau, ‘Local Border Reforms and Economic Activity’, Journal of Economic Geography, Vol. 22, 2022, pp. 81-102.

-

31 F. Roesel, ‘Do Mergers of Large Local Governments Reduce Expenditures? – Evidence from Germany Using the Synthetic Control Method’, European Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 50, 2017, pp. 22-36.

-

32 Ibid., did not find scale effects for total expenditures, administration and social care either.

-

33 R.W. Hahn & J.A. Hird, ‘The Costs and Benefits of Regulation: Review and Synthesis’, Yale Journal of Regulation, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1991, p. 237.

-

34 P.R. Rosenbaum & D.B. Rubin, ‘The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects’, Biometrika, Vol. 70, No. 1, 1983, p. 41.

-