From Legal Imposition to Legal Invitation

-

A Ann and Bob on a Visit

I first met Ann and Bob Seidman during a seminar at Leiden University back in 2002. They had come to Leiden to discuss topical issues of transnational legislation and at the time, they were particularly interested in the way EU Members States transposed EU directives into their domestic legal orders. An interesting, living laboratory for transplants this EU, even legal transplants – a phenomenon Bob and Anne had studied all of their lives. We met at my office and we sat down. The idea was that we would meet and discuss in very broad lines items that were on the agenda. The organizers of the seminar had said that it would be a brief interview of some 10 minutes in view of Ann and Bob’s already overstretched agenda. We sat and talked for almost 2 hours as I remember. The extent of their academic curiosity was amazing, their knowledge of legal systems and the way these system translate into societies and cultures breath-taking. Talking with Ann and Bob about their field of study and interest was like being taken on a magic-carpet ride throughout the world.

During the seminar they did a duo-presentation, which was enriching and cheerful. Bob submitted proposition A and Ann would react to it in a critical manner. Something we were not really used to, but a set-up we as an audience enjoyed immensely; it felt like you were visiting them in their lounge at home.

The questions and issues raised, however, were not ‘homely’ at all, but rather universal. The big issue of course being: can law bring about changes for the better to societies and their political systems? And closely connected to this: can ‘foreign’ or ‘transnational’ legal concepts and law successfully add to the transformative power of (domestic) law? You will notice I am not using the words ‘transplant’ or ‘implementation’ because to my mind they quickly confuse the issue due to their inherent hierarchical notion and reference to imposition. Transplant or implementation suggests that there is an element of obligation or command – a power difference. This power difference between imposing organization or state and the state or society implementing, is, I believe – not all too often – the articulated but presupposed drop back of some of the more heated debates on the possibility of legal transplants. It was not a critic of the idea of legal transplants that came up with the term, rather its most famous proponent. In his book Legal Transplants of 1974 Alan Watson argues that – because legal rules are largely autonomous from the larger social and cultural surroundings – legal concepts and rules – whole systems for that matter can successfully be borrowed from or transferred between (other) jurisdictions even where the circumstances of the host or recipient are different from those of the donor.1xA. Watson, Legal Transplants; An Approach to Comparative Law, Charlottesville, VA, University Press of Virginia, 1974. As cited by V. Perju, ‘Constitutional Transplants, Borrowing and Migrations’ (Chapter 63), in M. Rosenfeld & A. Sajó (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012, p. 1304-3127; and C. Stolker, Rethinking the Law School, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 271. This liberal approach of Watson was rejected by the opponent school of thought with Bob and Ann Seidman as some of its most famous and articulate advocates. As sociologists, they found it hard to believe that national or domestic characteristics of a system do not play a part in the transferability of legal norms and concepts, legislative solutions and institutions. Already back in 1972 Robert Seidman had argued that projects aiming to ‘import’ legal reform into a sociopolitical system from the outside could only be carried out provided they make a careful estimate of the probable consequences of a proposed legal reform (by way of a legislative programme). The estimate as a minimum requirement should include the cost and benefits to social organization, the cost of enforcement, the effect of sanctions, the probable nature of citizen reaction, the extent of probable noncompliance, and latent consequences of all sorts.2xR.B. Seidman, ‘Law and Development; A General Model’, Law and Society Review, Vol. 6, 1972, p. 338. Stolker, 2014, p. 271-272. Bob and Ann Seidman felt that law partly emanates from social relations and institutions within a society, and is not a sort of an add-on. Indeed law does have the potential to change social institutions (i.e. stable, valued and recurring patterns of behaviour) but not indiscriminately. In order to be able to do that, they must tie into or be embedded within a system. Existing social institutions – and behaviours flowing from them – must first be fully understood before laws and legal solutions aiming at reforming the existing institutions can be brought in. Therefore, Ann and Bob Seidman thought of themselves as ‘transforming institutionalists’ advocating that law reform projects should be approached as ‘social problem solving projects’. -

B However…Does It Hold True for Constitutional Law?

If I am not mistaken, Bob and Anne held the better side of the argument, certainly at the time. Transplanting legal solutions from one jurisdiction to another did not sit well in an era of neo-colonialism. It reminded of the legal impositions put in place by the once colonizing powers. Legal transplants were perceived by some as a sort of long arm of the Western powers to impose their will on transitional and developing countries in an indirect way. It did not chime well with the times. But the times seem to have changed.

The world we live in today is ‘globalized’ beyond recognition in comparison to the world of the 1970s and 1980s. Especially after 1989, when the third wave of democratization3xS.P. Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. University of Oklahoma Press1993. kicked in, the Soviet Union disintegrated, China opened up, and Latin America and large parts of Africa democratized; political systems all over the world seemed to be caught in a flux that – as a side effect – interconnected them in ways unfathomable before.4x See F. Fukuyama, The Origins of Political Order. Profile Books 2011. Although two decades later the third wave of democratization seems to be deflating somewhat, the ascent of liberal democracy-styled political model is astonishing. For some reason or the other, a lot of nations in the world have adopted the system of liberal democracy. A flood of new constitutions with the tell-tale liberal democratic institutions (rule of law, democracy, human rights, political freedom, division of state power, independence of the judiciary) give – at least on paper– evidence of this development. There are many constitutions, a lot of them are new and they are more alike than ever before. They are converging in both form and substance, as Anne Peters has noted.5xA. Peters, ‘The Globalization of State Constitutions’, in Janne Nijman & André Nollkaemper (Eds.), New Perspectives on the Divide between National and International Law. Oxford University Press 2007, p. 251-252. Why is that? Are they sets of legal transplants? Do they prove the legal transplant critics wrong?

Not really. Traditionally, the debate on legal transplants (as an element of the comparative law debate) predominantly revolved around private law. As Cheryl Saunders notes: “comparative law evolved historically, as a discipline concerned with private law, driven by the potential for harmonization. As a practical consequence, the expertise of most comparative legal scholars lies in private law.”6xC. Saunders, ’Towards a Global Constitutional Gene Pool’, UMelbLRS 2009, 25. Public law, especially constitutional law, differs from private law substantially, Saunders argues. And the differences between constitutional and private law affect comparative method and theoretical positions.7x Ibid. The nexus of constitutional law with traditions and culture seems to be less prevalent than that between private law and traditions and culture. Modern constitutions are momentous and man-made rather than a product of a slow evolutionary process of tradition (e.g. emerging from long-standing customs and customary law) and case law. Tom Ginsburg has pointed out that contemporary practices of constitution-making originate with bold acts of purposive institutional design involving borrowing, learning, accommodation and even with moments of creative innovation and experimentation.8xT. Ginsberg (Ed.), Comparative Constitutional Design. Cambridge University Press 2012, 1. Since the early days of modern constitutionalism, the ‘making’ of constitutions has always conveyed that they are ‘not found’.9xH. Pitkin, ‘The Idea of a Constitution’, Journal of Legal Education, Vol. 37, 1987, pp. 167, 68. They neither fall from heaven nor are they revealed in a mysterious way to Founders.10x See G. Frankenberg, ‘Comparative Constitutional Design’ (Review of the Book), International Journal of Constitutional Law, Vol. 11, No. 2, 2013, pp. 537-542. Instead, they are – as Ginsberg observes – drafted, framed, created, constructed and, yes, designed.11x Ibid. “Design implies a technocratic architectural paradigm that does not easily fit the messy realities of social institutions, especially not the messy process of constitution making.”12xGinsberg, 2012, p. 1.I Comparative Constitutional Scholarship

This does, however, not entail that comparative constitutional scholarship is all about shopping around in a globalized world. Although young in comparison to comparative private law, comparative constitutional scholarship is no stranger to controversy. The big question in a world of designing and borrowing is of course whether it is actually possible to successfully compare constitutions and constitutional systems, learn from it and, ultimately, even adopt elements from another constitutional system for domestic purposes.13x See P. Legrand, ‘The Impossibility of “Legal Transplants”’, Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, Vol. 4, 1997, pp. 111-124. In the Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law, Michel Rosenfeld observes that the debate among scholars concerning the legitimate scope of comparative work in constitutional law centres around three broadly defined positions.14xM. Rosenfeld, ‘Comparative Constitutional Analysis in United States Adjudication and Scholarship’, in M. Rosenfeld & A. Sajó (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012, p. 41 ff. Supporters of the first position claim that in fully fledged constitutional democracies, the problems of constitutional law, as well as the constitutional solutions to those problems, are by and large the same (or ought to be the same) in these systems. Hence, these problems and solutions can be more or less objectively studied and compared and lessons may be learned – irrespective of the specific wider context of the systems under study. Proponents of the second position agree that the problems of constitutional law are the same for all, but the solutions to the problems are likely to differ from one constitutional polity to the next, thus making it altogether difficult to learn from constitutional solutions in other systems, let alone transplant and adopt them. Analysis and comparison departing from this second position will be poised to highlight the differences between systems and try to place them in their proper context, thus possibly resulting in an understanding of why it is that constitutional systems differ from one another. Supporters of the third and last position assert that neither constitutional problems nor their solutions are likely to be the same for different constitutional systems. Comparisons, according to this last position, are most likely to be ultimately arbitrary, and comparativists’ choices and analysis are for that reason prone to be driven by ideology.15x Ibid, p. 41. Whatever position one would care to take, the methodological challenges for constitutional comparison are substantial. The fact that a one-on-one comparison is difficult and that there are risks involved in simple transplantation of constitutional solutions into different settings and contexts does not rule out, however, that no inspiration can be drawn from elements of other constitutions.

Whatever preference for whichever position one may hold, comparative constitutional law is affected by the undeniable convergence in constitutional law and constitutional law arrangements, especially over the course of the last 30 years. In Saunders’ view:(…) there has been and is likely to continue to be a significant degree of convergence of constitutional arrangements themselves, affecting text, institutional design, interpretation, and, somewhat more speculatively, values. This is not a phenomenon that is peculiar to the 21st century, but there are features of our times that have accelerated the process. Convergence contributes further to the ease of constitutional comparison and thus is useful for present purposes.16xSaunders, 2009.

She follows up with a warning:

It is not an unqualified good, however. The world of the 21st century has not attained a peak of perfection in the design and operation of constitutional arrangements, in terms of either acceptance or performance. There are advantages in a diversity of approaches to constitutional government and in a degree of competition between them; this, indeed, is one of the reasons for seeking a more global approach to comparative constitutional law. And as the circumstances change with which Constitutions must deal, constitutional innovation is required.17xSaunders, 2009.

Let us at this moment look in somewhat more detail into the growth and convergence of constitutions worldwide to better understand the dynamics and the way these developments touch upon comparative constitutional scholarship.

II The Rise and Convergence of Constitutions in the World

Of the 196 officially recognized countries in the world, today 19218xAccording to the website of Constitute.org. have a written constitution and four have a constitution although it is not laid down in a single constitutional document.19xUnited Kingdom, Israel, New Zealand and Saudi Arabia. Slightly inaccurately, we say that these countries have an unwritten constitution, but this is not always completely true. In the UK, for example, much constitutional law is indeed laid down in Acts of Parliament and Orders. Why do so many countries have a constitution? Various explanations can be given for this. One of these is ideological, perhaps even a little messianic by nature. The peoples of the world have become increasingly aware – almost an inevitability of the course of history – of what their natural rights are and that these rights are to be acknowledged and respected by national authorities. Also, the importance of democracy and its consequent right to self-determination are the apparently automatic result of a linear progression in human reason. The best place to anchor these achievements is in a constitution. A sacred fundamental document in which members of a political society make solemn promises to each other and usually entrench these in a complicated amendment procedure so that simple political majorities cannot hastily change the content. This explanation for constitutionalism (the form of a state that is based on a constitution) is sometimes reversed: not only are there many constitutions, a nation ought to have a constitution (and preferably one with a certain content). In recent years, I have come across many true constitutional missionaries in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, who without a trace of irony present the American constitution as the highest accomplishment in the history of mankind. To certain people, including some in my profession, constitutionalism is a kind of religion.

There are also somewhat more secular explanations for the increase in the number of constitutions in the world. Constitutions affect the economic growth of countries. The majority of these effects are indirect, but even so. One of these indirect effects is that constitutions can contribute to increased political stability in a country. The most recent constitutions do this not just by anchoring democracy, but also through constitutional guarantees for the legality of administrative action, the separation of powers and access to independent courts for the settlement of disputes. Democracy checked in this way has proven to be a demonstrable20x See R. Cooter, The Strategic Constitution, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1999. and proven recipe for political stability,21xT. Persson & G. Tabellini, The Economic Effects of Constitutions, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 2003. in other words the opportunity to peacefully and periodically be able to change government. By entrenching this institutional balance in an amendment and revision procedure that requires super-majorities for constitutional revision or even several procedural steps or readings, a political system becomes less sensitive to disturbances, and minorities – always a vulnerable group in majority systems – are better protected. Political stability lessens uncertainty, increases the probability of ‘return on investment’ and as a result increases the possibility of economic growth. Constitutions and the institutions they create (in particular an independent judiciary) provide an answer to the problem of ‘credible commitments’. If political leaders want to stimulate long-term economic growth, they will have to convince and reassure national and foreign investors. Two critical factors for economic growth, after all, are the existence of transparent foreseeable laws and regulations on the one hand and a judicial regime that permits capital accumulation and protects property rights on the other hand.22xR. Hirschl, ‘The Political Origins of the New Constitutionalism’, Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2004, p. 82. Market discipline therefore contributes to the establishment of democratic and constitutional administrations defined/secured by modern constitutions. That is not to say though that once political systems have a constitution they strictly adhere to the rules laid down in it. This would explain why national constitutions are in such demand and also – in part – why in so many countries throughout the world that are not dependent on market discipline (because of great mineral wealth or a mainly self-supporting economy), liberal, i.e. democratic, constitutions governed by law are not so easily or quickly established.

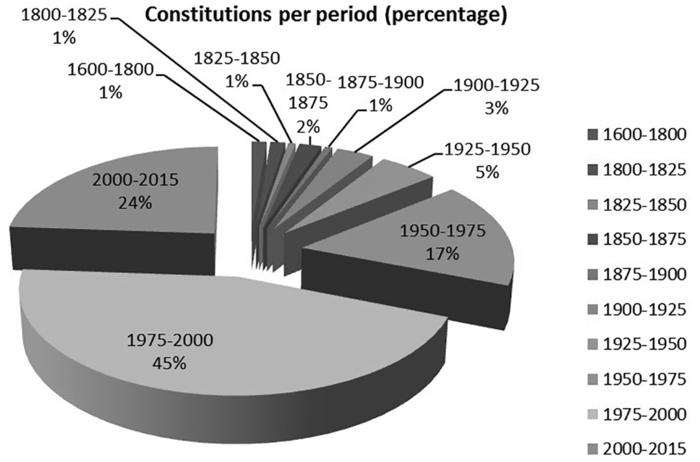

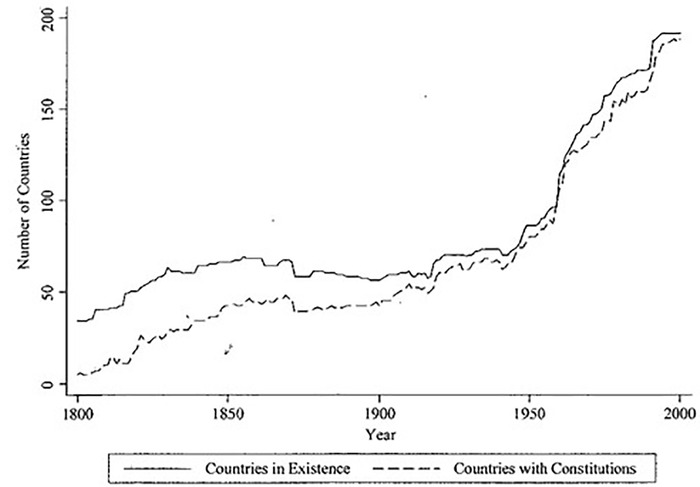

The increase in the number of constitutions is actually a relatively recent phenomenon. A total of 88% of all 192 constitutions throughout the world came into existence after 1950, and 69% after 1975 (see Figures 1 and 2).23xIn the calculation, two ‘constitutions’ dating back to before 1787 have been included. These, however, are not constitutions in the modern sense, but rather so-called ‘charters’ and the like. They do not affect the period after 1787 in which the US Constitution is the oldest.Figure 1: Percentage of national constitutions still in existence by period of time. Figure 2: Growth of the number of constitutions in time 1787-2005

Figure 2: Growth of the number of constitutions in time 1787-2005

The pattern illustrated in the figures follows – though with some delay – that of global recognition of the ‘rule of law’ and human rights acquired through the UN (including the right to self-determination) soon after the Second World War, decolonization and the great surges of democratization. The number of democratic constitutions governed by law – overrepresented in the period after 1990 – can be explained by the most recent large surge of democratization on the one hand and by the forces of market globalization on the other hand. The dynamic of the globalized market economy may be a driver for the rapid growth of liberal democracies, liberal democracy-styled constitutions and convergence of constitutions and constitutional institutions.

The relationship among constitutions, markets and economic growth is not new, even though it is increasingly becoming controversial. Present-day lawyers and constitutional lawyers, who dominate the debate in constitutional design and comparative constitutional law, are in their analyses more likely to look for lofty moral values and fundamental legal principles than mundane actors and factors such as businesses, markets, wealth accumulation and economic growth. That does, however, not mean that markets and the economy, which are of quintessential importance for human existence in the world today, are not relevant or do not bear a lot of weight when it comes down to explaining modern constitutional developments. One recent and relevant insight in this respect is, for instance, that there seems to exist a demonstrable relationship between welfare and the age of a constitution.24xZ. Elkins, T. Ginsberg & J. Melton, The Endurance of Constitutions. Cambridge University Press 2009. The research on the age of national constitutions, by Elkins, Ginsberg and Melton, shows that a static positive correlation exists between the age of a constitution and GDP per capita, the democracy and the political stability in a country. Second, it showed a static noticeably negative correlation (be it only slight) between the age of a constitution and the probability of a political or economic crisis.25xElkins et al, 2009, p. 30. This effect does seem to reflect in the 2012 list of the then ten richest countries in the world26xCalculated by the IMF in 2012 <http://financieel.infonu.nl/geld/86950-top-10-rijkste-landen-ter-wereld-20112012.html> (last visited 25 April 2015). measured by GDP per capita.

Luxembourg – 1868

Qatar – 2003

Norway – 1814

Switzerland – 1999 (1848 in actual fact)

Australia – 1901

United Arab Emirates – 1971

Denmark – 1953 (1849 in actual fact – annual Constitution Day celebration on 5 June)

Sweden – 1974 (from 1810 – various constitutional documents)

The Netherlands – 1814

Canada – 1867

Although a top ten does not say all that much without the rest of the list added to it, the overrepresentation in the first ten positions of old constitutions is not a coincidence altogether. Copying and borrowing of constitutional solutions and the rise of constitutions over the last three decades is not only explained by the fact that different jurisdictions/political systems sympathize with the idea of the rule of law, democracy and human rights, because of the strength of the arguments or views expressed and therefore copy it. Or that it is a token of the ascent of global civilization, as some, endorsing idealist views of constitutionalism, would like to believe. Political systems and jurisdictions do adopt constitutions and copy constitutional solutions because they believe they will benefit from it in the global marketplace. Not only directly but also indirectly – nations with a modern constitution are more likely to be perceived as reliable, peaceful and ‘decent’ international partners. This explains why nations sometimes adopt quite foreign constitutional institutions to present themselves as reliable partners or suitable candidates for a club or a regional association. In the spirit of Bob and Anne, I will give one rather local illustration.

III Accession of Ten New Member States to the EU – Meeting the Mark

After the Berlin wall came down in 1989, countries in central and Eastern Europe transformed their political systems from formal party-led socialist democracies into liberal democracies. Most of them wanted to join the European Union quickly, hoping for freedom and prosperity and the assurance of not falling back into the Russian sphere of influence. Although eventually trying to limit the number of members, the EU pursued talks with ten countries, including two Mediterranean ones, Cyprus and Malta. In the end eight Central and Eastern European countries (the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia) joined on 1 May 2004: the largest single enlargement in terms of people, and number of countries, in EU history. The EU, however, did not simply let these countries in. There were conditions to the entry: candidate countries had to meet the Copenhagen criteria – set out by the then 15 Member States of the EU in 1993. The Copenhagen criteria are the essential conditions all candidate countries must satisfy to become a Member State. These are:

Political criteria: Stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities.

Economic criteria: A functioning market economy and the capacity to cope with competition and market forces.

Administrative and institutional capacity to effectively implement the acquis 27xThe term for the body of common rights and obligations that is binding on all the EU member states. and ability to take on the obligations of membership.

In the 5 years prior to the accession, the EU Commission set out to verify whether or not the candidate countries were up to these accession standards. This vetting process started with a diagnosis on how the candidate country rated on these criteria ending with a report detailing to what extent the candidate met with the standards, in what respects it fell short and what elements were considered vulnerable. This was of course a politically highly sensitive exercise. Once the first diagnostic reports were drawn up, it was clear that most of the countries still had some work to do before their system, including the constitutional system, was up to standards. The reports were structured into different chapters, one of them being that of the rule of law – on which I will focus from here on. Indeed most of the candidate countries had human rights in place as well as the basic democratic institutions, but some of the countries had issues with the protection of minorities and the independence of the judiciary. Under the communist system, the judiciary itself was deeply influenced by the ruling party and the government. Public prosecution and the agencies operating it were totally under the control of the government administration. In a Western conception of the rule of law, the judiciary must be independent and impartial and the public prosecution’s office cannot be a mere extension of central government. To change the judicial system overnight was of course a tall order for the candidate countries. It was not only a matter of legal institutions but also of people with ‘ancient régime’ training and mindsets, with vested interests and jobs. In order to help these candidate countries, busloads of experts were flown in on EU-subsidized seminars in the countries in order to give inspiration and ideas for solutions that could be helpful in meeting with the exigencies of ‘the chapters’. I myself have been in a dozen of these seminars in all of the eight Central and Eastern European candidate countries. From these seminars I learned a lot about these new neighbours in the EU, but it taught me something about constitutional convergence as well. First of all, it taught me that constitutional design (helping countries to solve constitutional problems) is both a vocation and a business. I met a lot of ‘constitutional salesmen’ coming from all over the globe. To be honest, I believe I unwittingly was one of them. My ‘product’ was comparative insights into ‘Councils for the Judiciary’. A council for the judiciary is a sort of a self-governing judicial organization or body that functions independently from the government and parliament and acts as an intermediate institution (a ‘buffer’) between the legislative-executive branch of government and the judiciary. Typically, it does not administer justice as such, but performs ‘meta-judicial’ tasks such as disciplinary action, career decisions by judges, the recruitment and professional training of judges, coordination between courts, general policies, courts’ service-related activities (budget, housing, automation, finances and accounting, etc.), etc. as regards judges and courts.28x See W. Voermans, ‘Judicial Transparency Furthering Public Accountability for New Judiciaries’, Utrecht Law Review, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2007, p. 148-159. These councils, we had learned in 2000 when we studied them comparatively, come in different types and sizes, under different labels and have different responsibilities and competences.29xW. Voermans & P. Albers, Councils for the Judiciary in EU Countries, European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ), Council of Europe, Strasbourg, 2003. Generally, they function as independent intermediates between the government and the judiciary in order to ensure and guarantee the independence of the judiciary in some way or in some respect. These Councils for the Judiciary are booming throughout Europe. A survey by the Consultative Council of European Judges (CCJE) shows that twenty-seven countries out of thirty-eight do have a council for the judiciary in place. Most of them have been established quite recently in the last two decades.30xW. Voermans, ‘Councils for the Judiciary in Europe: Trends and Models’, in F.R. Segado (Ed.), The Spanish Constitution in the European Constitutional Context. Dykinson 2003, p. 2133-2144.

Comparative insights into these Councils for the Judiciary were in great demand with these candidate countries because – on the face of it – they had the potential to make the judiciary more independent from the government. Their ‘buffer’ capacity did create a demonstrable, tangible effort that candidate countries were committed to do away with undue influence on it. But, of course, the establishment (or just considering it) of such an institution will not in itself solve the many issues and problems the candidate countries had with the independent functioning of their judiciary. As a transplant, most of the time it was a strange fruit and a cosmetic exercise giving lip service in a time-pressured vetting process by the EU.

This anecdote of course does not give solid evidence for anything but it does show that a lot of countries and jurisdictions may have hosts of ulterior motives when it comes down to constitutional borrowing and copying of constitutions or constitutional instruments. This may explain in part the remarkable speed of constitutional convergence throughout the world.IV When Anne and Bob Visited

When Anne and Bob visited, they were not only very curious about the EU and EU directives. They had also heard that there was talk of an EU Constitution. They asked me again and again about what I felt about the issue and I do believe they loved the ardour with which I, as a still very young and inexperienced professor, spoke about this EU Constitution. They had sniffed out a ‘true believer’. In my then still naïve belief in constitutionalism I was convinced that the EU, vexed by its diversity, could benefit from a common Constitution. Common constitutional ground could make the Union fairer and more democratic; it could bring the peoples of the EU nearer to each other, like once the US Constitution, the recent Spanish Constitution or the French Constitution(s) had done. Bob and Anne were less convinced. In response I dangled the convergence argument in front of their eyes. In the 50 years or so that the EU had already existed, the constitutional systems of the EU countries had even more aligned than they did before. We were decades on the road of convergence and we were all stemming from the same root anyway. So why not take the next, almost inevitable step. Bob and Anne smiled. ‘Differences might be more important than shared elements and common places’, they told me (or words to that effect). And they were right, so I learned later on. It is as Cheryl Saunders says:

the extent of convergence should not be overestimated. No Constitution is exactly the same in form or operation. Constitutional concepts have different meanings in different system. In any event, Constitutions are complex organisms. To some degree at least, every Constitution is affected by its history, including the circumstances of its making; the context in which it operates; the often unarticulated assumptions on which it is based; the priority accorded to particular values; and a tendency to develop organic characteristics over time. The significance of these features may be mitigated, but it is unlikely to be eliminated, by the forces for constitutional convergence.31xSaunders, 2009.

I did not meet Anne and Bob again after 2002 when they made such a huge impression on me during their visit. But, when on 1 June 2005, to the shock and horror of many, the Dutch people, with their 200-year-old constitution, voted the draft EU Constitution down with an astonishing 61.6% majority in a national referendum, I dreamed of Anne and Bob: they smiled and I was forever grateful that I had learned a very valuable lesson from them that has helped me to a better understanding.

Noten

-

1 A. Watson, Legal Transplants; An Approach to Comparative Law, Charlottesville, VA, University Press of Virginia, 1974. As cited by V. Perju, ‘Constitutional Transplants, Borrowing and Migrations’ (Chapter 63), in M. Rosenfeld & A. Sajó (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012, p. 1304-3127; and C. Stolker, Rethinking the Law School, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 271.

-

2 R.B. Seidman, ‘Law and Development; A General Model’, Law and Society Review, Vol. 6, 1972, p. 338. Stolker, 2014, p. 271-272.

-

3 S.P. Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. University of Oklahoma Press1993.

-

4 See F. Fukuyama, The Origins of Political Order. Profile Books 2011.

-

5 A. Peters, ‘The Globalization of State Constitutions’, in Janne Nijman & André Nollkaemper (Eds.), New Perspectives on the Divide between National and International Law. Oxford University Press 2007, p. 251-252.

-

6 C. Saunders, ’Towards a Global Constitutional Gene Pool’, UMelbLRS 2009, 25.

-

7 Ibid.

-

8 T. Ginsberg (Ed.), Comparative Constitutional Design. Cambridge University Press 2012, 1.

-

9 H. Pitkin, ‘The Idea of a Constitution’, Journal of Legal Education, Vol. 37, 1987, pp. 167, 68.

-

10 See G. Frankenberg, ‘Comparative Constitutional Design’ (Review of the Book), International Journal of Constitutional Law, Vol. 11, No. 2, 2013, pp. 537-542.

-

11 Ibid.

-

12 Ginsberg, 2012, p. 1.

-

13 See P. Legrand, ‘The Impossibility of “Legal Transplants”’, Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law, Vol. 4, 1997, pp. 111-124.

-

14 M. Rosenfeld, ‘Comparative Constitutional Analysis in United States Adjudication and Scholarship’, in M. Rosenfeld & A. Sajó (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012, p. 41 ff.

-

15 Ibid, p. 41.

-

16 Saunders, 2009.

-

17 Saunders, 2009.

-

18 According to the website of Constitute.org.

-

19 United Kingdom, Israel, New Zealand and Saudi Arabia. Slightly inaccurately, we say that these countries have an unwritten constitution, but this is not always completely true. In the UK, for example, much constitutional law is indeed laid down in Acts of Parliament and Orders.

-

20 See R. Cooter, The Strategic Constitution, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1999.

-

21 T. Persson & G. Tabellini, The Economic Effects of Constitutions, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 2003.

-

22 R. Hirschl, ‘The Political Origins of the New Constitutionalism’, Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2004, p. 82.

-

23 In the calculation, two ‘constitutions’ dating back to before 1787 have been included. These, however, are not constitutions in the modern sense, but rather so-called ‘charters’ and the like. They do not affect the period after 1787 in which the US Constitution is the oldest.

-

24 Z. Elkins, T. Ginsberg & J. Melton, The Endurance of Constitutions. Cambridge University Press 2009.

-

25 Elkins et al, 2009, p. 30.

-

26 Calculated by the IMF in 2012 <http://financieel.infonu.nl/geld/86950-top-10-rijkste-landen-ter-wereld-20112012.html> (last visited 25 April 2015).

-

27 The term for the body of common rights and obligations that is binding on all the EU member states.

-

28 See W. Voermans, ‘Judicial Transparency Furthering Public Accountability for New Judiciaries’, Utrecht Law Review, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2007, p. 148-159.

-

29 W. Voermans & P. Albers, Councils for the Judiciary in EU Countries, European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ), Council of Europe, Strasbourg, 2003.

-

30 W. Voermans, ‘Councils for the Judiciary in Europe: Trends and Models’, in F.R. Segado (Ed.), The Spanish Constitution in the European Constitutional Context. Dykinson 2003, p. 2133-2144.

-

31 Saunders, 2009.