13th Sir William Dale Memorial Lecture

Driving too fast in all the circumstances

Failing to make any or any proper use of his trafficator

Our job is to produce a result that works, but also one that the reader can readily understand.

The reader has an inherently difficult task and needs as much help as we can give them.

It’s an honour, and humbling, to be invited to give this lecture in Sir William Dale’s memory.

Dale was a civil servant, a lawyer, a writer, an educator, and a reformer. Most of all, Dale spoke and wrote and taught on the subject of law making and legislative drafting and their importance in any free country. And we are here this evening because we recognise, like him, that how a nation puts its values into law is truly important.

Dale’s book, ‘Legislative Drafting: A New Approach’, a critique of the British legislative drafting style, was at the centre of the movement in the mid-1970s to overhaul the way laws were made. His book still deserves a place on the library shelf, as does the other great product of the debate, The Renton Report, published in 1975.

During the last years of his career, Dale concentrated on a comprehensive investigation into what legislative style would best meet the needs of newly independent countries. He advocated legislation that is accessible and easy to understand “written in terms comprehensible to non-lawyers”. He talked about simplification of the law-making process, about clear and effective legislation devoid of unnecessary details and linguistic complexity. He encouraged “man and woman to read and know the laws”.

Word for word, I adopt Dale’s manifesto. In fact, the Cabinet Office’s ‘good law’ programme flies his flags: our laws should be effective, clear, necessary, coherent, and accessible.

Inspired by his wide-ranging and stimulating writing, I would like to explore what the Dale challenge meant in the 1970s; what it would have meant to earlier generations; and what it means to us today. Dale’s work inspires us to look at the history of law making. Law after all, among all our institutions, is best known for its continuity. It changes, of course; but its purpose, its role in society, the way it mediates between the people and the institutions of the State: these are remarkably constant.

As any law student quickly learns, changes made to the law rely on a continuous narrative thread connecting new law to what has gone before. It is as true for statutes as it is for common law. And yet, within that continuity, there is always for the lawmaker an itch to do things differently – because the vehicle we use to convey the law is language, and language changes; because increasing complexity brings new challenges for readability; because law is written to be read and acted upon, and its readership changes; and because the way in which people read it, the format they use, changes too.

So let’s look at continuity: the role the law plays, and in particular statute law, in a democracy. One of the things you notice when you look at the chronological index of statutes is that it tells a history of our nation. Not necessarily the history, but a version of our history. You can track, in the names of statutes, Britain’s politics and preoccupations over the years.

The struggle between King and Barons with Magna Carta. The Act of Union, creating Great Britain. Acts for the building of railways and canals. Acts turning the British adventure in India into an Empire ruled from London. And then, 90 years later, an Act giving India its freedom. An Act in 1915 introducing the Old Age Pension. An Act in 1920 giving women the vote. An Act in 1948 setting up the National Health Service. Acts to nationalise. Acts to privatise. An Act in 2013 allowing marriage equality.

So you can plot our economic or political history but also the social history. Writers probably do it better, but Parliament usually keeps up. Look, for example, at these:

(Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist, and the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, which set up workhouses.)

(Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist, and the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, which set up workhouses.)

(Virginia Woolf, Night and Day, and the Representation of the People Act 1918, which gave women the vote.)

(Virginia Woolf, Night and Day, and the Representation of the People Act 1918, which gave women the vote.)

(Noel Coward, Blithe Spirit, and the Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951.)

(Noel Coward, Blithe Spirit, and the Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951.)

(Martin Amis, Money, and the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991.)

(Martin Amis, Money, and the Dangerous Dogs Act 1991.)

But statutes and English literature, though they sometimes cover the same ground, deploy language to very different ends. Law has authority. Law creates rights that can be enforced. Law instructs the officials of the State to act in a particular way: the tax collector, the judge, the marriage registrar, and the hangman.

Law is the rules we set, by which we agree that society will be ordered. Law always reflects the spirit of the times, and it is therefore always moving, but it has a timeless purpose and character.

Here is WH Auden, struggling to define law, like love, by reference to anything but itself:

Law, say the gardeners, is the sun,

Law is the one

All gardeners obey

Tomorrow, yesterday, to-day.Law is the wisdom of the old,

The impotent grandfathers feebly scold;

The grandchildren put out a treble tongue,

Law is the senses of the young.Law, says the priest with a priestly look,

Expounding to an unpriestly people,

Law is the words in my priestly book,

Law is my pulpit and my steeple.Law, says the judge as he looks down his nose,

Speaking clearly and most severely,

Law is as I’ve told you before,

Law is as you know I suppose,

Law is but let me explain it once more,

Law is The Law.(W.H. Auden: Law, like Love)

And so that index of the statutes reminds us not just of our nation’s story but also of the trust we have continuously placed in law as an operating system. Law is infuriating, baffling. Perhaps, it will also be so. It regulates a complicated society, and it is not always in human nature to embrace or understand rules.

But law is important – for reasons that we, like Auden’s characters, may disagree over or struggle to articulate. It is certainly too important for us to allow it to become obscure or inaccessible as well. And bringing the law to citizens, making it accessible, making it easy is a tough job. There are many forces that make law difficult.

I would like to pay tribute to the men and women whose vocation it is to write our laws. I can say that without immodesty, as I am not a professional law drafter myself. Parliamentary Counsel works incredibly hard to solve problems, to bring sense to sometimes inchoate policy, and to render huge amounts of detail with both the accuracy needed to see off legal challenge as well as the readability to inform citizens and parliamentarians.

And it’s the magnitude of the lawmakers’ task in bringing difficult law to citizens that often gives them a keen interest in new technical, linguistic, stylistic, and technological techniques.

So let’s turn to innovation. It would be nice to think that the history of law making is one of continuous improvement. But I doubt that’s the case. I suspect that improvement has been rather less linear and more episodic. I also suspect that there have been periods in history when law making has got worse, rather than better.

For example, medieval statutes were once drafted in Latin or Norman French. They were not only in the wrong language; they were terse, laconic, and obscure. We then moved to the writing of legislation in English, by lawyers accomplished in conveyances and other documents: an improvement perhaps, but the terseness was replaced by verbosity and repetition.

In the 19th century, changes in society and the economy encouraged users (by then a larger group) to demand clearer and coherent legislation: laws that could help people do business in an industrial age. So law drafters made their appearance in the Treasury and the Home Office. We saw Statute Law Commissioners commenting on ‘the imperfections in the statute law’. In 1861, a series of Statute Law Revision Acts began, getting rid of a vast quantity of obsolete legislation. Acts got short titles. Then in 1869, the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel was set up. We started to see uniformity in how laws were written.

I like to see this as the Victorians at their industrious and fastidious best: categorising, cataloguing, and bringing order – as they did in so many other fields like botany, anthropology, and archaeology.

In the 20th century, revision and repeal became precious instruments for law makers. And statute law itself started to colonise vast areas of the common law – such as the great sequence of property statutes of 1925. These were magnificent achievements, though the colonising trend means that the modern statute book is now truly vast.

Fast forward to the 1960s – and the demand for better laws returned. The Law Commission was created, mostly addressing the inadequacies of the common law. In 1975, the Renton Report made 121 recommendations to simplify the statute-making process. In 1977, William Dale advocated a new approach to drafting that would make “statutes comprehensible to the ordinary man”. This was the law catching up with the plain English movement. In fact, Sir Ernest Gower’s Plain Words had appeared in its first form as a pamphlet for HM Treasury in 1948. It’s interesting to observe that law writing was perhaps a little slow to ‘get’ plain English.

Sometimes, you look at pre-Renton legislative drafting, and you conclude that the task of the drafter was to convey a difficult idea in as few words as possible. Take an example from the National Insurance Act 1946, highlighted in the Renton Report:

For the purpose of this Part of the Schedule a person over pensionable age, not being an insured person, shall be treated as an employed person if he would be an insured person were he under pensionable age and would be an employed person were he an insured person.

It’s brilliantly clever, but I think I can safely say that nobody would draft like that today. The central theme of both Dale and Renton – that legislation must speak to the probable reader, not to someone who likes to solve fiendishly clever word games – is widely accepted. One of my favourite bits of statute is Section 3 of the Theft Act 1978: “Making off without payment”. It talks of ‘making off’ when ‘payment on the spot’ is required or expected. It’s not just non-technical language: it’s almost demotic.

So where and what is the need for innovation today? The task of rendering legal ideas as comprehensibly and clearly as possible – the Dale challenge – is as pressing as ever. It should never stop. Society, and language, does not stand still.

Innovation lies at the heart of good legislative drafting. This doesn’t mean modishly following every linguistic fad. But it does mean being prepared to turn off the beaten track where this will give the best result in a contemporary context. And it does mean knowing how language is used and understood by the law’s likely users. Of course, any new law needs to work alongside older law and older usages. The drafter must always have that in mind. But there is a particular danger in allowing precedent and the perception of safety that it brings, to create barriers for new readers. Or, even worse, nonsense.

You get the same danger in other areas of legal writing too. When I was a bar student in 1988, we were taught how to write pleadings in a road traffic case. The model pleading would go something like this:

Particulars of negligence

What on earth is a trafficator, we asked. Well, our barrister tutor told us, it’s the device you use to signal an intention to turn left, or to turn right. You mean indicator, we asked. No, he said, the correct legal term is trafficator.

Just in case you think 1988 was before the dawn of time, here is what a car looked like in 1988:

And here is a trafficator:

Most drafters spend their lives deeply immersed in existing legislation: poring over old Acts, working out how they operate, and how best to amend them. It can be difficult to put aside the comforting allure of a precedent. But the good drafter will have the experience and confidence to weigh up the relative merits of following a well-worn path or striking out over fresh ground; and she will have the freedom to do the latter where this is the simplest and most direct way to express an idea.

And so the philosophy of the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel is to set the right conditions for this process to take place. We don’t encourage innovation for its own sake. That would be pointless and could produce very bad law indeed. But what we try to do is create a climate where innovation is supported and allowed to flourish, to address particular difficulties as they arise. We must listen to feedback. We must seek it out. We must do user testing as a matter of practice. And so, legislative drafting will continue to evolve.

Over the past 20 or so years, innovations in drafting techniques are usually in recognition of two things:

The first example of this is the increasing use of textual amendments in preference to non-textual amendments. Textual amendments are not always possible, and they do tend to mean longer Bills. But readers tell us that they are infinitely preferable to the accumulation of glosses and double-takes that result if we say that statute A has to be read subject to statute B and statute C.

The second example is the use of navigational aids to help users work their way around the statute book and to understand the complex relationships between different provisions. We have more signposts – for example, in this year’s Pensions Act, which reads:

For transitional cases in which a person may be entitled to a different state pension, see sections 4 and 12.

And we have more overviews. For example, Section 236 from the Housing and Regeneration Act 2008 says:

This group of sections allows the regulator to award compensation to a victim of a failure on the part of a registered provider.

Views differ about whether it is right for legislation to include navigational aids or other inert material without a substantive legal affect. The Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments doesn’t much like it. But generally, people seem more open to it than they might have been 20 years ago.

The third area of innovation relates to the way that logical sequences are expressed in statutes, and information is presented. There has been an increasing use of short sentences and tables.

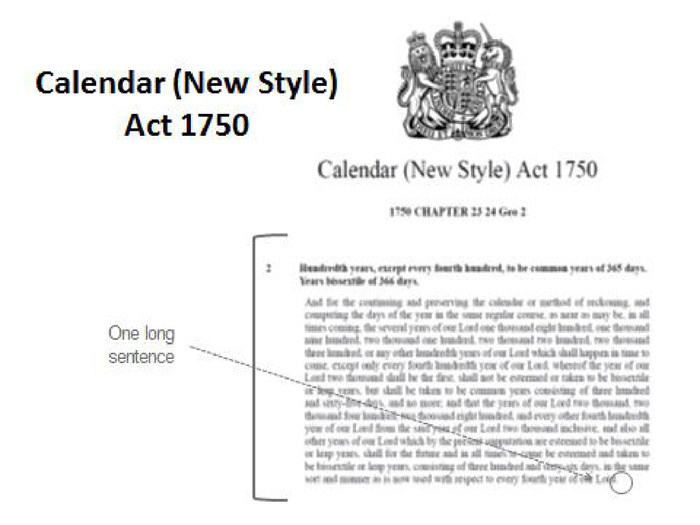

On short sentences, take one stark example. This is Section 2 of the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, and this huge block of text is one long sentence:

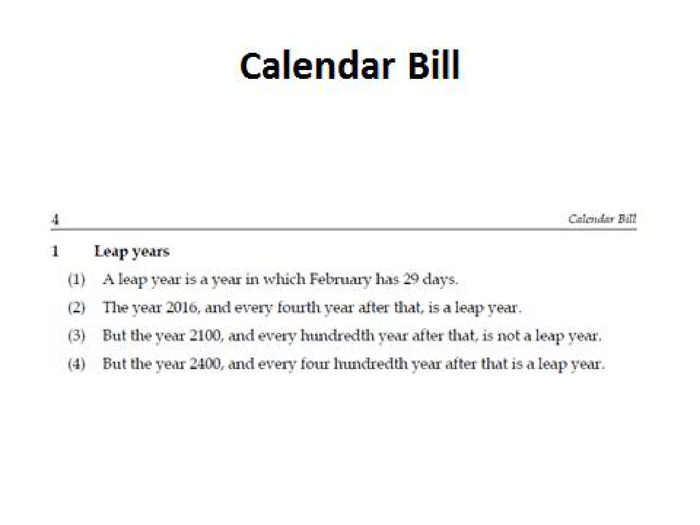

If we were to draft this provision again in 2014, it would look completely different. How? Well, we might at least break down the sentence:

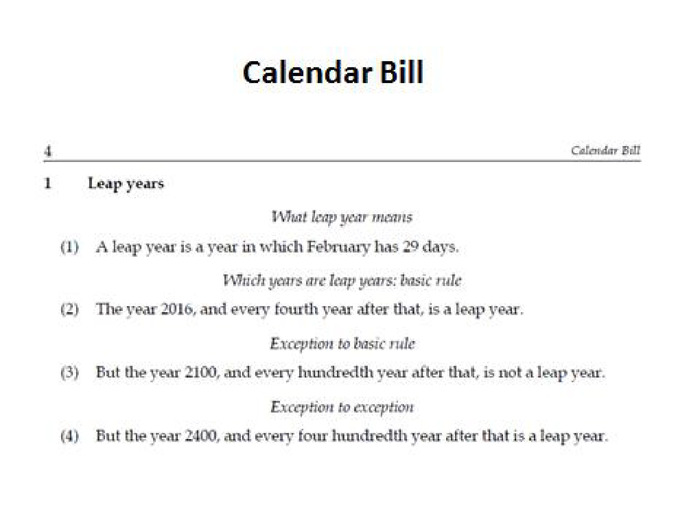

We might also add headings:

But given that what the section is doing is presenting some simple data rules, might there be an even clearer way of doing it if we departed from the convention of using only sentences and numbered paragraphs? Bear that thought in mind when we look at law as data a little later.

Equally, I could talk about the use of cases and illustrative examples. Or mathematical formulae. I could tell you about new usages that have been tried and abandoned, or modified. For the drafter, however, the question is always, who will be reading this and what will work best for them?

More broadly, we are today in the middle of a change in how law is used that is as significant as the switch from Latin into English. It requires and rewards innovation on the part of all of us involved in making laws. The drivers of this change are openness, citizen engagement, and technology. We all know about the impact technology is having in the way we interact with each other and the way we expect institutions to interact with us. You see it in e-petitions and consultations. You also see it in social media.

Citizens are finding a voice in how they are governed; how their train companies are run and in the rules that shape their lives, their businesses, and their communities. In order to explore what that means for us, I want to extend the concept of law making to include at one end, the policy formulation process, and at the other end, the business of publishing legislation.

So, what happens if policy makers start to turn away from regulation as a means of achieving social change? What if the starting point ceases to be reforms delivered through organisations and agencies and public bodies?

That’s not entirely fanciful. Innovative policy making tends not to mean a single solution to problems. There is a realisation that social ‘problems’ are quite complicated things, made up of how people behave, their health, how their community or their neighbourhood works, how rewards and incentives are arranged, what makes a particular estate tick, or a particular family. It’s also recognition that public services are experienced by real people, who don’t always respond in the way we might imagine in a government department.

This new policy making might feel experimental, small scale, rapid, local, and personal. It might take advantage of real-time data or behavioural science. It might use prototypes, and it won’t be afraid to fail. It might also take advantage of people’s skills and enthusiasms. It will watch where the energy and ideas are in the space outside government, and it might act merely as a catalyst or a facilitator or a convenor. Some of this new policy might not need much by way of enabling powers or legislation. It might deliver an outcome not through direct government intervention at all, but through a social impact bond that’s backed by an investment fund. Or through an app that someone has designed using flood data from the Environment Agency. Or through a service run by a social enterprise that has benefited from targeted tax relief.

Open policy making is worth a separate lecture, but it is clear that with the right skills and approach, the potential to transform policy making by doing it openly is huge. Even if ‘national policy into national law’ remains the model, how might citizens start to get involved in policy making and even in law making?

Here are some examples:

In Ecuador, the Casa Legislativa are virtual and physical forums to connect citizens and institutions. People can watch parliamentary debates, attend regular Q&A sessions with parliamentarians, or access government archives.

In the United States, the OpenGov Foundation has developed an open-source, public engagement tool that allows individuals to play a direct role in writing legislation. The program is called Madison, and it was first developed by a Californian Congressman to crowd source ideas to amend the Stop Internet Piracy Act.

In Estonia, osale.ee is a platform where citizens and interest groups can launch initiatives for new legislative proposals, can participate in public consultations, and can find information about proposed policy decisions and laws.

Or, look at eDemocracia in Brazil. It’s a platform to consult people on policy, legislation and implementation, test draft legislation directly with users, and even crowd source legislation. Lawmakers and citizens can propose solutions to policy problems. Its first product was the Youth Statute Bill; 30% of it was built based on the ideas submitted by e-Democracia participants.

So, might opening up policy to new evidence and to new voices make democracy stronger? Might it make policy, and even legislation, better? These are early days; the evidence is thin and all of us can point to risks. But, even if participatory law making and crowd sourced legislation seem far-fetched, maybe you can think of specific cases where a more collaborative approach would help to identify pitfalls in the legislation or in the way it will be implemented. Certainly, the crowd-sourcing component of the Cabinet Office Red Tape Challenge generated insights that simply would not have emerged by traditional consultations alone.

What about citizens asserting themselves as consumers, users, of legislation? Where does that take us? How might that affect law making?

We know that between 2 and 3 million people are accessing legislation on <legislation.gov.uk> every month.

This collection of people is a far bigger and more diverse group than has ever read legislation before. Some are legally qualified. Most are not. They are people doing their jobs: maybe they are Human Resource professionals. Maybe they are environmental activists or landlords in dispute with their tenants. Perhaps, they are merely curious citizens.

Remember Dale’s enthusiasm for thinking about legislation in terms of the user. Historically, we have tended to be more aware of the needs of institutional users (parliamentarians, the judiciary, public bodies and corporations) and lawyers. Now, we need to understand better the expectations of a much wider user base. We also need to understand that those new users will have different expectations.

For example, we are all used to searching for information online. We are quite spoiled because nowadays we quickly find the information we need, no matter how technical or obscure. We are used to the power of search and personalisation.

I am no different. I have an app giving me data on every bus in London. I have it set it up to tell me about the number 45 and the 63. I have an app that can give me weather data for every city on the planet. I have told it to ignore all but London and Barcelona.

With the law, though, the situation is different, because our legislation, complex as it is, needs a map. Lawyers have been trained in a sort of informal, passed-down map that lets you surf the wonderful web that is the statute book. But what about non-lawyers? Those millions who access <legislation.gov.uk>? They are using laptops, PCs, tablets, and mobiles.

What if one of our non-lawyer users is trying to deal with the aftermath of a car crash. Will she look for ‘torts’? Is this injury and damage from an act? Is this injury to a person or in general? Or to a property? Should she look for ‘crimes’?

This might sound silly to some, but consider this: the titles of legislation often give her no hint of the content, unless she already knows what is in there. And then, she is up against extent, commencement, and amendment. None of her inquiries are particularly difficult legal questions. It’s not jurisprudence that is defeating her; it is plain information retrieval.

So, it looks like we have to develop new tools to solve a timeless problem. It is the same problem as the one addressed in the Middle Ages when Parliament decided to make laws in English rather than Norman French. But where is this round of innovation going to come from?

Well, we can today count on a powerful combination of low-cost cloud computing, open-source analytics software, and new ways of researching data. These are the building blocks of what has become known as legal informatics.

If we look at the complicated web of statutes as data, then legislation can be formalised (and visualised) as a mathematical object, a hierarchically organised structure containing language, and explicit interdependence between provisions. That insight is what will allow law makers to innovate. It will allow them to create new tools, which will transform the user’s experience.

The publishing end of the law-making machine is at the National Archives in Kew, publishers of <legislation.gov.uk>:

The changes they have made since the launch of <legislation.gov.uk> in 2010 mean that users can now compare the original text of legislation versus the latest version and view a timeline of changes using a slider for navigation, exploring any given moment in time. Legal informatics will make it possible to organise in a sensible, intelligible way the 50 million words in the statute book and the new 100,000 words added or changed every month.

<Legislation.gov.uk> will soon be completely up to date. And it is already publishing legislation in HTML. It has the capacity to produce on-demand PDFs of a given document and provides API access for third-party developers and internal users and bulk data downloads. Of course, that’s not nearly enough. Today’s users of legislation are discerning and demanding. They want more.

So it’s possible to think of a carefully mapped statute book, reorganised into thematic or geographic categories. Categories that are still a reflection of accurate legal taxonomies of course. But that also resonate with non-lawyers. Perhaps, user-centred categories correlated to real-life needs. A flexible categorisation system perhaps where legislation can be ‘tagged’ more than once and so be put into different categories.

Why couldn’t we, for example, provide legal information that is highly tailored to a specific problem, linked to relevant guidance materials, and with up-to-date notifications on commencement and maybe penalties? A virtual codification. Digital, personalised, legal codes. The personalisation of legal publishing. The equivalent of the bus app, or the weather app.

Everything <legislation.gov.uk> does is underpinned by user testing, API, and Linked Data. What that means is that once new legislation is recorded, it is infinitely convertible from one format to another. Natural language processing will enable amendments to be detected and applied. With those foundations in place, the possibilities of what can be done with legislation data are now almost limitless. It creates opportunities for large commercial legal publishers. But also for new entrants and legal start-ups.

Like mobile legislative app, iLegal, its content is derived from the <legislation.gov.uk> API and it has a few nice features, like offline access to all items of legislation. It costs users a fraction of the price of traditional comparable services. But the interesting new developments in the field of legal informatics don’t stop with user-friendly publishing. We are also seeing a quiet revolution in the legal sector: a new breed of providers and applications of legal data we could not have imagined a few years ago.

So immediately, the traditional practice of lawyering is under threat from digital legal services that substitute the lawyer as the main intermediary between the citizens and legislation. And today, innovation and technology are encouraging new actors to explore new markets. The first off the mark were apps for road accidents. You take a picture, record your location, submit the details to a company that helps you with insurance claims, and all the rest of it. Or you can get an app that claims to offer easy-to-understand advice about divorce law.

Another app, Shake, puts legally binding documents at your fingertips. Non-disclosure agreements, contracts of hire, equipment rentals. Legal transactions for the startup set.

Legal Atlas maps visualise and compare legislation across the world.

Or Virtual Courthouse, a startup in Washington that provides legal information and step-by-step, tailored self-representation support to low-income individuals who are priced out by traditional lawyers. Their services are becoming increasingly popular in the United States, where there is no civil legal aid.

So, if law is to be consumed or packaged as data; if it becomes a product consumed without intermediaries, will we start to write it as data? Or at the very least, to write it in a way that allows it to be machine readable? Can you do human readable and machine readable at the same time?

I suspect that whether we like it or not, informatics, computing, and technology are going to change both what it means to practise law and to ‘think like a lawyer’. Innovations such as e-discovery and automated document generation are already having significant effects on the legal services market.

Some predict lawyers will be redundant in 20 years. I doubt it. But I think that the future will also generate different dynamics between law makers and users. Channels and tools will be created, or will evolve, or will disappear. And yes, of course, this will affect how laws are made and how they are written.

If we act together, we can reduce legal burdens and legal friction. We can improve the law; transform the perception of the law; and strengthen the rule of law. I think it is an opportunity Sir William Dale would embrace wholeheartedly.

Picture by Walter Bird.

Picture by Walter Bird.

©Crown copyright 2015. Reproduced with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office/Queen’s Printer for Scotland and the Cabinet Office.