Historical abuse in Dutch Catholic institutions: an ex ante evaluation of institutional and non-institutional response procedures

-

1. Introduction

‘Dutch Fathers accused of sexual abuse’ headlined the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad on 26 February 2010 (Dohmen, 2010). This was the first newspaper report publishing about – what later turned out to be – rampant historical abuse within Dutch Roman Catholic Church institutions, particularly in schools operated by the Church. These broadcasts incited public outrage and ignited a national debate. The abuse scandal – with an estimation of between 10,000 and 20,000 victim-survivors between 1945 and 2000 (Deetman et al., 2011) – was only one of similar worldwide scandals. In Belgium, the United Kingdom, Australia and Germany public debates were also instigated, catalysing the establishment of committees tasked with amassing reports of clergy abuse in institutions (Spröber et al., 2014). Most of these reports addressed sexual abuse that had occurred decades earlier, predominantly between 1945 and 1970 (Klijn, 2015). The dominant focus of these public inquiry reports was to better understand the nature, scope and causes of the abuse. In Ireland, for example, there was evidence of physical, sexual and emotional abuse and neglect of thousands of underage boys and girls (Terry, 2015). The Belgian report showed that abuse occurred over a 70-year period (Adriaenssens et al., 2010) and that 628 victim-survivors reported their sexual abuse (Belgische Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers, 2017; Verhoeven & Aertsen, 2017). Recommendations for preventing abuse in the future were provided, including better education and training about abuse, the need to respond quickly and thoroughly to victim-survivors, transparency around abuse and coordinated responses with civil authorities (Terry, 2015).

It is notable that although the reports detailing abuse in the Dutch Church (Deetman et al., 2010, 2011; Deetman, 2013) and the reports of the official Church bodies often mention recognition and repair, (1) these terms are not explicitly defined in these documents (KNR, 2015) and, (2) surprisingly, little emphasis has been placed on recognition and repair in response to the harm done not only to the victim-survivors but also to their next of kin. In acknowledgment of the critical place of recognition and repair, we first follow the definitions as described in a report detailing sexual abuse within institutions and foster families. Herein recognition explicitly confirms that the victim was harmed and that this never should have happened. Repair is defined as not only recognising the harm in words but also giving an apology by the respective institutions, orally or in writing, and offering financial compensation. Although money cannot undo the suffering, a financial compensation provides some reparation for victim-survivors (Van Rij, 2017). Second, so-called secondary victims of clergy abuse, such as (grand)children, partners and other relatives, may also suffer as a result of the offences perpetrated on the victim-survivors (Courtin, 2015; Ellis & Ellis, 2014; Kudlac, 2006; Wind, Sullivan & Levins, 2008). These reverberating effects of harm can be seen as ripple effects. It has been argued that given the impact of the abuse on secondary victims, the same acknowledgment and approaches to recognition and repair are required that are given to the primary victims (Courtin, 2015).

The disclosure of the widespread abuse in the Netherlands was facilitated by an abundance of media attention within a short time (Houppermans, 2011). With this disclosure, victim-survivors started to organise themselves to demand justice from Dutch Church authorities and the Dutch state. Neither the Church nor the state were prepared for the exposure of this mass victimisation. They were at a loss as to how to handle mass scandal and felt that there was no appropriate legal response they could fall back on (Chatelion Counet, 2020).

It soon became apparent that victim-survivors could not obtain justice through criminal and civil law (by filing a tort claim) or by submitting a request for compensation with Help & Justice, the agency tasked with complaints of sexual abuse of women and minors within the Church. The agency was established by bishops and religious superiors in 1995 and depended, both financially and administratively, on the bishops and the religious orders (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). Criminal and civil law have relatively strict rules regarding the burden of proof (Van Dijck, 2018). Consequently, it is remarkably difficult to prove abuse that was committed decades ago. Furthermore, the statute of limitations can arise in both criminal and civil proceedings. In addition to criminal and civil law, Help & Justice was not equipped to handle the torrent of reports (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). To overcome these obstacles, three complaint and compensation procedures were developed to give victim-survivors a platform for recognition and repair through alternative avenues. Moreover, two mediation procedures were established for those who did not want to use the formal complaint and compensation procedures. These procedures are not ‘legal’ in a strict sense, but were all clearly structured and governed by certain agreed upon rules. We therefore refer to these procedures as ‘regulated modalities’.

When mapping the various procedures available in the Netherlands between 2011 and 2015, we distinguished between institutional and non-institutional responses to show that the Church itself has often been in charge of determining which forms of recognition and repair are given. This ties in neatly with literature showing that much more attention needs to be given to the fact that institutions, being themselves responsible for the harm, often determine the instruments of recognition that are applied or withheld (Immler, 2022; Ludwin King, 2017). We use the term ‘responses’ to describe the various procedures put in place. We see these procedures as responses made by the Church to the harm incurred by victim-survivors and their demand for recognition and repair (Aertsen & Schotsmans, 2020).

A feature of the five developed response mechanisms is that although (sexual) abuse is a criminal offence, they were either initiated by the Church itself or by victim-survivors in collaboration with individual congregations. However, combatting criminal offences and compensating victims of those crimes and their relatives when the offender cannot pay are governmental tasks. Hence, many countries have set up state compensation funds and support services for crime victims who cannot get compensation from offenders as well as specific compensation schemes for those falling outside the scope of these funds (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014; Milquet, 2019).

The aim of this study is an ex ante evaluation – future-oriented research into the expected effects and side-effects of potential new regulations following a structured and formalised procedure, leading to a written report (Verschuuren & van Gestel, 2009) – of the regulated modalities for victim-survivors of clerical abuse. Herein, we explain the purpose and the design of the different proceedings, with the intention of subsequently analysing them. More specifically, we examine what can be expected from the institutional and non-institutional response procedures in terms of recognition and repair.1x ‘Institutional’ – in this context – refers to the institution of the Church and concretely refers to response mechanisms that have been initiated by the Church. ‘Non-institutional’ refers to the response mechanism that has been initiated by victim-survivors themselves, thus without the assistance of an institution. Drawing from relevant theoretical and empirical literature, we formulate hypotheses about these procedures’ potential to reach these outcomes (Verschuuren & van Gestel, 2009).

First, we outline the methods we used. Second, we situate our case study in the broader literature on the mechanisms of recognition and repair of historical abuse in Catholic institutions. We then proceed with the description and rationale of the procedures. Subsequently, we propose the two theoretical lenses of procedural and restorative justice through which we analyse the design of the procedures and their ‘promise’ of recognition and repair. These lenses are in accordance with the procedures. For example, we analyse the mediation procedures through the lens of restorative justice. Lastly, we reflect on the lessons that can be drawn from the procedures. -

2. Methods

This research is part of a larger project studying how response and redress procedures addressing historical abuse in Catholic institutions in the Netherlands are perceived by the recipients and whether these procedures keep their promise of offering recognition and repair. This article is based on desktop research of the most relevant literature on historical abuse in Dutch Catholic institutions and some interviews with relevant stakeholders. We based our data largely on a knowledgeable selection of articles on response procedures for victim-survivors of historical clerical abuse. This aided us in identifying trends and better understanding the current state of the field (Huelin, Iheanacho, Payne & Sandman, 2015). We accessed works of Van Dijck (2018) on the Reporting Centre – a complaint and compensation procedure – and of Goosen (2016) and Klijn (2015), respectively the mediator and arbiter attached to Triptych restorative mediation. This article is based primarily on reports of the nature and scope of sexual abuse in the Church (Deetman et al., 2011; Deetman, 2013) and the evaluative report of the activities of the Reporting Centre between 2011 and 2018 (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). We also used the work by Aertsen and Schotsmans (2020), detailing the relationship between victim-survivor and institution regarding response procedures and the institutional dimension of repair in Belgium. This latter article is particularly useful because it broadens the need for recognition and repair to actors such as the Church as an institution and to society itself.

To gain a better insight into the role of the Church, the decision-making processes of actors involved with the procedures, their rationale and overall fact-checking, we additionally conducted a series of semi-structured interviews with stakeholders (N = 5). Furthermore, two stakeholders pointed us to a number of relevant texts, which we had not found through our desk research, such as information leaflets detailing the response procedures. Three stakeholders were directly involved with the development of the complaint and compensation procedures Reporting Centre and the Final Action. These were the former Chairperson of the Complaints Committee, the former Chairperson of the Compensation Committee, and the former head of the overarching Reporting Centre. Furthermore, a legal secretary/confidential adviser involved with the implementation of Triptych restorative mediation and the former Chair of the Conference of the Dutch Religious were interviewed. In these semi-structured interviews we looked for answers to what constituted ‘institutional’ mediation, one of the two mediation procedures. The five interviewees were identified by the first author, and the suitability of the respondents was further validated, because the respondents named each other as viable interviewees. Since all interviews were conducted in Dutch, we translated the quotes from Dutch to English. -

3. Historical institutional clergy abuse: mechanisms of recognition and repair

There is an abundance of literature on historical institutional clergy abuse, often tackling the psychological impact and effects of the abuse on victim-survivors’ physical and emotional states. Victim-survivors of clergy abuse often experience symptoms of grief, anger, depression, sexual dysfunctions, sleep disorders, trauma, rage and distress (Fogler, Shipherd, Rowe, Jensen & Clarke, 2008; McGraw et al., 2019; Terry, 2008; Van Wormer & Berns, 2004).

Conversely, very few studies have investigated whether redress procedures established to compensate harm by clergy are successful in achieving recognition and repair through procedural justice and restorative practices. There has been some literature dedicated to redress procedures, with a focus on Anglo-Saxon countries such as Ireland, Australia and the United States (Courtin, 2015; Daly, 2018; Ellis & Ellis, 2014; Gallen, 2016; Matthews, 2015). For example, in the United States, redress procedures via civil courts paid out large sums of compensation, and Canada and Australia used a mixture of public apology, reparation, compensation and truth commissions (McAlinden & Naylor, 2016). Overall, it was found that procedures that were accessed or put in place to offer repair to victim-survivors of historical clergy abuse were often unable to honour their promise of offering repair (Balboni & Bishop, 2010; Courtin, 2015; Ellis & Ellis, 2014). Many redress procedures were found to be adversarial, opaque, initiated from the top-down and to encourage power imbalances not only between victim-survivors and the Church but also among victim-survivors themselves, perpetuating hierarchical structures that were often blatant within the ‘harming’ institute and that were being mimicked in peer support groups (Courtin, 2015; Daly, 2018; Ellis & Ellis, 2014). These Anglo-Saxon countries all had approaches which differed to a greater or lesser extent from the procedures put in place in the Netherlands. For example, Ireland has no statute of limitations for historical (sexual) abuse since it was retrospectively amended by law in 2000 (Bisschops, 2014). Australia’s common law position on vicarious liability and non-delegable duties means that victims of historical child sexual assault have no recourse through civil avenues (Courtin, 2015; Matthews, 2015).

Recent research from Southern Europe on abuse perpetrated by clergy and justice mechanisms suggests that criminal courts impose higher sentences and adjudicate larger monetary sums to victim-survivors of clergy abuse compared to victims of other institutional settings (educational and sports centres). Moreover, the average length of the prison sentences imposed on these religious leaders was higher than that found in a previous study conducted in clerical context (Tamarit, Padró-Solanet, Guardiola & Hernández, 2017). One possible explanation for this punishment of clerical abusers was that their behaviour was considered more blameworthy than that of other abusers (Tamarit, Aizpitarte & Arantegui, 2021), but no clarification for this explanation was given. While an extensive literature review was carried out on the most recent research on child sexual abuse by members of the Church that occurred in Italy and France, the overview lacked a focus on redress procedures (Marotta, 2021). We therefore respond to the call for action that ‘more analysis and study work [needs to be] undertaken against the background of yet other models of historical institutional abuse in other countries’ (Aertsen & Schotsmans, 2020: 35).

Procedures established in the Netherlands were internationally praised. For example, the Triptych restorative mediation has been considered unique and promising:Because there is no consistent approach globally to helping victim-survivors in the Catholic Church to heal, it may be beneficial for other countries to review the approach taken in the Netherlands and consider implementing a similar restorative approach. (Terry, 2015: 149)

What makes this observation striking is that scholarly research on Dutch procedures appears to be very scarce. Previous research focused solely on outcomes of the Reporting Centre, analysing whether what was offered to victim-survivors filing a claim matched their demands and what impacted the probability of victims obtaining certain types of non-monetary relief (Van Dijck, 2018). Therefore, an in-depth analysis of the procedures that are undertaken is required in order to better assess whether and in what ways they are fulfilling their ‘promise’.

-

4. Institutional and non-institutional response procedures: description and rationale

Following Aertsen and Schotsmans (2020), who use the term ‘response models’ (responsmodellen) for redress procedures to offer recognition and repair in the aftermath of historical institutional abuse and violence in Belgium, we categorised the five Dutch proceedings into institutional and non-institutional response procedures. Institutional responses are: (1) Reporting Centre for Sexual Abuse within the Roman Catholic Church in the Netherlands (2011) (hereafter abbreviated to Reporting Centre), (2) Commission for Help, Recognition, and Reparation for violence against minors in the Roman Catholic Church (hereafter abbreviated to HEG Committee (Commissie Hulp, Erkenning en Genoegdoening), 2013), (3) ‘institutional’ mediation (2013), (4) Final Action (2015). The first, second and fourth procedures have primarily been developed to provide financial compensation to victim-survivors of clergy abuse. ‘Institutional’ mediation was developed as a dialogical counterpart for the hearing within the Reporting Centre. Triptych restorative mediation (hereafter abbreviated to Triptych mediation, 2011) was the only non-institutional response, a dialogical procedure initiated by victim-survivors in collaboration with individual congregations, aiming to establish monetary compensation. We now look at each of these responses.

4.1 Reporting Centre: the first institutional act

In 2011, an independent Management and Monitoring Foundation was set up, and it included the following bodies: the Reporting Centre, the Complaints Committee, the Compensation Committee and the Victim Support Platform (Sanders & Spekman, 2018).

The Victim Support Platform had as its most important task the organisation of initial care and short-term confidential counselling for claimants.2x When describing the response procedures, we use the term ‘claimant’ instead of ‘victim-survivor’. Here, we chose to use the juridical term, since it concerns regulated response procedures. It also considered requests for help for partners and family members and the psychological screening for the referral of individuals for specific psychological help (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). This is in compliance with the duty of care as recommended by Deetman et al. (2010), also known as Committee Deetman.3x In March 2010, former MP Wim Deetman became the Chair of this Committee, and he was asked by the Bishops’ Conference and the Conference of the Dutch Religious to conduct an independent inquiry into sexual abuse in Dutch Catholic institutions (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). All bishops in the Dutch Ecclesiastical Province form the Bishops’ Conference of the Netherlands, a permanent consultative body, in which the bishops jointly formulate and implement policy in various fields. The Bishops’ Conference members comprise seven resident bishops, their auxiliary bishops and titular bishops who fulfil a function in the Dutch ecclesiastical province (www.rkkerk.nl/kerk/kerkprovincie/bisschoppenconferentie/). The Conference of Dutch Religious is the umbrella organisation of (almost) all religious orders and congregations in the Netherlands. It represents the interests of friars, nuns and brothers and encourages cooperation between various monasteries (www.knr.nl/over-knr/wie-zijn-wij/).

If claimants chose to report their abuse, they were referred to the Complaints Committee, where they could submit their complaint in writing. This complaint was forwarded to the defendant or, if they had passed away, to a representative of their congregation, who could respond to the complaint with a statement of defence. In most cases, there was a hearing by the Complaints Committee where both parties were heard. A hearing is in line with the recommendation of Committee Deetman (2010) for the Church to enter into dialogue with the claimants. According to this Committee and as stated by the former head of the Reporting Centre, it is important that claimants have the opportunity to tell their story to people, instead of feeling that ‘they are fighting against a system or an institution’.4x Interview with former head of the Reporting Centre (21 January 2022). This dialogical element was supposed to offer relief to claimants.

Monetary compensation was possible if a complaint was accepted as authentic by the Complaints Committee. Committee Lindenbergh formulated five categories of financial compensation – according to the severity of the abuse – ranging from €5,000, in the lowest category, to €100,000, in the highest category (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). The Compensation Committee made a conscious decision to exclude personal contact between claimant and defendant and members of the Committee so as to speed up the proceeding, on the one hand, and to avoid claimants bringing up their (painful) story again.5x Interview with the former Chairperson of the Compensation Committee (21 December 2021).4.2 HEG Committee: broadening the definition of abuse

In 2013, a report on the abuse of and violence against girls and women was published (Deetman, 2013). This was because claimants – mostly female – had experienced harm other than sexual abuse but were initially left out of the first report of Deetman et al. (2011) and were considered to be ineligible for filing a complaint with the Reporting Centre. This new report led to the establishment of the HEG Committee by the Church in 2013 (Sanders & Spekman, 2018).

Although the HEG Committee operated independently from the Reporting Centre, similarities arose between the two procedures. Again, in principle, personal contact between the claimant and the defendant was to be avoided, and complaints were predominantly handled in writing. If the complaint was deemed authentic, claimants received a written apology on behalf of the Bishops’ Conference (Bisschoppenconferentie) and the Conference of Dutch Religious (Konferentie Nederlandse Religieuzen; KNR), together with the amount of financial compensation. However, the amount of financial compensation differed drastically from the amounts paid by the Reporting Centre. The compensation ranged from €1500 to €5000. Why these amounts were chosen is not clear. The (relatively) low amounts to be paid out meant that the burden of proof was forfeited (Bisschops, 2014). In addition, all claimants received an offer for more comprehensive support (Sanders & Spekman, 2018).4.3 ‘Institutional’ mediation: institutional dialogue

The omission of (female) claimants who experienced psychological and physical abuse within the Reporting Centre was not the only criticism directed against the procedure. Its complaint procedure was found to be undesirably judicialised and adversarial by victim organisation Umbrella National Consultation on Church Child Abuse (Koepel Landelijk Overleg Kerkelijk Kindermisbruik; KLOKK) (Bisschops, 2014). Various victim organisations, including KLOKK, Mea Culpa United (MCU), Women’s Platform for Child Abuse in the Catholic Church (VrouwenPlatform Kerkelijk Kindermisbruik; VPKK) and the Board of the Management and Monitoring Foundation identified mediation as a response to tackle these problems (Sanders & Spekman, 2018).

Starting in 2013, the option of mediation was given when, during the oral hearing, the Chair of the Complaints Committee believed there was a possibility for the parties to reach a settlement (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). Mediation was also used as an alternative to the complaints procedure. This form of mediation was guided by Perspectief Herstelbemiddeling (formerly Slachtoffer in Beeld), a non-governmental organisation that arranges victim-offender mediation (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). Regardless of the outcome of the mediation, claimants could opt to take their claim to the Compensation Committee.

According to the former head of the Reporting Centre, ‘institutional’ mediation was not fundamentally different from general mediation in cases of sexual abuse committed outside the Church.6x Telephone conversation with former head of the Reporting Centre (13 May 2022). However, the ‘traditional’ mediation was somewhat tailored to accommodate claimants and defendants. ‘Institutional’ mediation was aimed mainly at repair, recognition and closure for the claimants rather than, as is a characteristic feature of mediation, two parties moving forward together. ‘Institutional’ mediation specifically took into account non-cooperating or deceased defendants.4.4 Final Action: a deadline for claims

In 2015, the Church initiated Final Action to provide satisfaction and compensation for claimants whose complaints had not been granted previously (Van Dijck, 2018). Whereas the Church was deemed the official initiator, it was again a victim organisation, VPKK, but also the former Chairperson of the Complaints Committee, that led the development of Final Action. The former Chairperson of the Complaints Committee’s motivation was that many victims’ complaints had been dismissed owing to a lack of supporting evidence, a maladministration he had earlier proclaimed publicly (Dohmen, 2013).

Again, the involvement of claimants ended at the start of the procedure. There was no personal contact, and Final Action turned out to be more administrative in nature. The original claim which was rejected in the Reporting Centre or the HEG Committee was transferred to the Final Action Committee, who amended and accepted the claim on paper (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). But this meant that claimants could not directly engage with the Committee or the Church after receiving the outcome of the complaint.

The name Final Action is quite telling because it put pressure on claimants who were reporting the abuse. This ‘deadline’ mindset was also contested by VPKK. Because of the decline in the number of complaints, the Conference of Bishops and the Conference of Dutch Religious established a submission deadline of 1 July 2014. In 2014, VPKK took legal action, contesting the closing date.7x Civil Chamber, 1 October 2014, ECLI:NL:RBMNE:2014:4604. The outcome was a court ruling that the deadline had to be extended to 1 May 2015 (Sanders & Spekman, 2018).4.5 Triptych mediation: a non-institutional response to the Reporting Centre

Beginning in 2011, and in tandem with the development of the Reporting Centre, ideas for what would later be known as Triptych mediation were developed. The driving force was the peer support group ‘Boys of Don Rua’ and the accused Congregation of the Salesians of Don Bosco. These bodies were searching for an alternative to the regulated, institutional proceedings, in the absence of faith in the original agency Help & Justice and the newly developed Reporting Centre. This lack of trust stemmed from two sources: (1) the impossibility of filing a complaint against a deceased defendant with Help & Justice until mid-2011 and (2) the required supporting evidence – even though the threshold of proof was low – within the newly established Reporting Centre proved to be nearly impossible for many claimants and led to complaints being declared as unfounded (Klijn, 2015). In addition to reports of sexual abuse, reports of psychological and physical abuse and serious negligence in providing care and education could also be included in the mediation and financial compensation (Goosen, 2016). The main difference between Triptych mediation and ‘institutional’ mediation is that the former was established by victims themselves and the latter by the Church itself.

The core of Triptych mediation was formed in a conversation between claimant, defendant, a Congregation member representing the defendant, with supervision by a mediator. The mediation was developed as an ongoing process in the three phases of the Triptych mediation, namely, (1) an inventory report, (2) mediation resulting in a settlement agreement and (3) a compensation proposal by an arbiter (Goosen, 2016; Klijn, 2015). The usage of the same information in all the three phases was designed to be the healing element (Goosen, 2016). Three features of Triptych mediation were vital for its success, namely confidentiality, objectivity (Goosen, 2016) and care. The practice of confidentiality in mediation encourages freedom of speech for both parties and could make it easier for the accused party to denounce historical abuse. Regarding objectivity, the abuse that has been established between the parties was objectified as monetary compensation (Goosen, 2016). Care was an essential element, as stated by the confidential adviser, who needed to interact with claimants during the entire procedure. She not only provided them with information about the procedure and imminent decisions on their case but also needed to be available if claimants had questions or needed (emotional) support.8x Interview with legal secretary/confidential advisor Triptych mediation (14 January 2022).

A key feature of Triptych mediation was that – as in classical mediation settings – the two parties’ close involvement helped shape the procedure. Victim-survivors came up with the name Triptych mediation themselves, expressing the idea of equality for the parties concerned and ensuring that their ideas, opinions and voices were included in the process. Another recognition of inclusion was the emphasis on dialogue (Klijn, 2015) and a conscious attempt to move away from antagonistic procedures and to create a space where all parties could be heard and recognised (Bisschops, 2014; Goosen, 2016). -

5. A procedural and restorative justice approach

Previous research following historical institutional clergy abuse had the outcomes of the Reporting Centre as its focus (Van Dijck, 2018). To counter this focus, we recognise the importance of acknowledging procedural aspects of all complaint and compensation procedures that were established in the Netherlands as a result of historical institutional clergy abuse. We also analyse the mediation procedures through a restorative lens to see whether or not they live up to their promise of offering recognition and repair.

5.1 Procedural justice

Justice processes are typically evaluated by their outcomes (Pemberton, Aarten & Mulder, 2017). Research, however, indicates that claimants also care deeply about the process through which conflicts are resolved and decisions made (MacCoun, 2005 in: Mulder, 2013). Indeed, the importance of procedural fairness for victim satisfaction with and evaluation of outcomes ‘is one of the most robust findings in the justice literature’ (Brockner et al., 2001: 301 in: Rottman, 2007). Reference to procedures and decisions that help shape and inform an outcome, and the impact that this has on how participants feel they have been treated and whether or not their needs have been met, has become increasingly important and is considered to be ‘procedural justice’ (McAlinden & Naylor, 2016).

Work on procedural justice began with the publication, by Thibaut and Walker, of their Theory of Procedural Justice in 1978. They contended that people are concerned about fair procedures because they generate fair outcomes, which in the long run maximises the individual’s desired results (Wemmers, 1996). By 1988, Lind and Tyler modified the original model to better understand the significance of procedural justice. This resulted in the most familiar elements of procedural justice being described as four pillars: neutrality, respect, trustworthiness and voice (Tyler, 2000 in: Van Camp & Wemmers, 2013). Neutrality and trust are related to the quality of the decision making. Neutrality stands for the perception of honesty, impartiality and objectivity displayed by the decision maker. Trust is related to the assessment of the authority’s motives and the use of their discretionary competences. Respect and voice are related to the quality of treatment by the decision maker (Blader & Tyler, 2003). Respect is about interest, friendliness, opportunity, consideration and influence (Wemmers, 1996). Voice is defined as the opportunity for the disputants to participate in the conflict resolution procedure and present their concerns (Van Camp & Wemmers, 2013: 120-121).

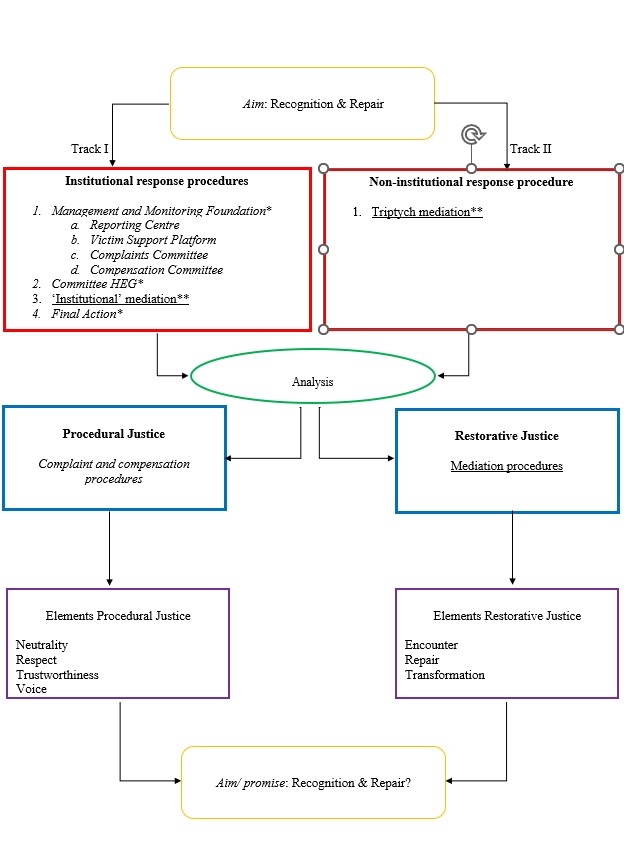

For these reasons, we analyse the complaint and compensation procedures (Reporting Centre, HEG Committee and Final Action) within the procedural justice framework. Emerging scholarship suggests that for recognition and repair, the procedure as such is, in fact, the crucial aspect (Lecuyer, White, Schmook, Lemay & Calmé, 2018; Lau, Gurney & Cinner, 2021 in: Ruano-Chamorro, Gurney & Cinner, 2022). Since research on procedure is lacking, we evaluate the three complaints and compensation procedures through the lenses of neutrality, respect, trustworthiness and voice as the first track of analysis in this article (articlesee figure 1). The second track, the analysis of ‘institutional’ mediation and Triptych mediation through a restorative justice model, is presented in the following paragraph.5.2 Restorative justice

As victim-offender mediation (VOM) is a restorative practice, it is often discussed within the restorative justice field (Goosen, 2016; Noll & Harvey, 2008; Terry, 2015; Van Camp & Wemmers, 2013). With its focus on interpersonal relationships, human need and collaborative problem-solving processes (Zehr, 2004), mediation fits seamlessly within the restorative justice framework. Restorative mediation (such as VOM) is a private, voluntary, informal and party-controlled process where legal representatives or other supporting representatives may or may not be present, depending on the desires of the parties (Noll & Harvey, 2008: 389). The purpose of a restorative intervention is conciliation and healing, instead of punishment (Zehr & Mika, 1998 in: Van Camp & Wemmers, 2013).

The emergence of the restorative approach is related to the denunciation of the harmful effects of incarceration and punishment, the rediscovery of the victim, and the need to restore a ruptured community and crumbling traditional institutions (Faget, 1997 in: Van Camp & Wemmers, 2013). Restorative justice isan approach that offers offenders, victims and the community an alternative pathway to justice. It promotes the safe participation of victims in resolving the situation and offers people who accept responsibility for the harm caused by their actions an opportunity to make themselves accountable to those they have harmed. It is based on the recognition that criminal behaviour not only violates the law, but also harms victims and the community. (UNODC, 2020: 4)

The European Forum for Restorative Justice (EFRJ) uses a similar definition of restorative justice. It describes restorative justice as

an approach for addressing harm or the risk of harm through engaging all those affected in coming to a common understanding and agreement on how the harm or wrongdoing can be repaired and justice achieved. (European Forum for Restorative Justice, 2021: 11)

In this definition, both a participatory element (‘all those affected’) and a restorative orientation (focused on solution, common understanding, agreement on remedying damage or injustice and obtaining justice) are clearly present as components (Aertsen & Schotsmans, 2020). This aligns with the key concepts of restorative justice, namely encounter, repair and transformation (Johnstone & Van Ness, 2007). All parties participate voluntarily in an encounter with each other and are meaningfully involved in the discussion and decision about the repair and justice process (Johnstone & Van Ness, 2007). Repair concerns not only the victim-survivors’ need for healing but also the offender’s need to make amends and the community’s need for relational health and safety (Restorative Justice Exchange, n.d.). Furthermore, restoration of community order, peace and healing of damaged relationships is needed (UNODC, 2020). Transformation is defined as restorative encounters which create spaces that lead to transformed individuals and pinpoint root causes of crime, particularly, but not only, systemic and structural fault lines. Once identified, these systemic aspects of harm can be faced, dealt with and potentially be changed to foster more just systems and healthier, safer communities (Restorative Justice Exchange, n.d.). Restorative justice emphasises recognition and repair not only for victim-survivors but also for their next of kin and the broader community. As such, it takes into account ripple effects of harm, on the one hand, and repair on the other (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2014; Johnstone & Van Ness, 2007)

While there are multiple definitions of restorative justice, none consider restorative justice as explicitly aimed at delivering a procedurally just and fair manner of responding to crimes or disputes (Hoyle & Batchelor, 2018). Rather, as argued by De Mesmaecker (2011), restorative justice uses procedural justice as a mechanism through which restorative justice ‘works’ (Hoyle & Batchelor, 2018). Thus, restorative justice and procedural justice are intertwined, allowing for an appropriate comparison between the two forms of justice.

Recognition and repair of the involved parties are also often seen to be the fundamental values or aims within a restorative justice frame. Searching for recognition is all about having recognition and having a standing in a group. The restorative approach is appropriate in response to this need (Van Camp & Wemmers, 2013). The analysis of ‘institutional’ mediation and Triptych mediation through a restorative justice model, using the lenses of encounter, repair and transformation, is the second track of analysis in this article (see Figure 1).9x To clarify, in Figure 1, we categorised ‘institutional’ mediation under track I since it is a response procedure instigated by the Church. However, we analysed ‘institutional’ mediation with a restorative justice lens, and it therefore falls under track II. -

6. Evaluating the response procedures through the lenses of procedural and restorative justice

In the following two paragraphs we consider how institutional and non-institutional response procedures potentially lead to recognition and repair. We do this by, first, evaluating the Reporting Centre, HEG Committee and Final Action on the basis of the four pillars of procedural justice: neutrality, trustworthiness, respect and voice. Second, we evaluate ‘institutional’ mediation and Triptych mediation using the three key features of restorative justice, namely encounter, repair and transformation.

6.1 Procedural justice: Reporting Centre, HEG Committee and Final Action

We first consider neutrality. All three responses complied with the principle of neutrality. The complaint and compensation committees in the procedures and the Victim Support Platform in the Reporting Centre were made up of former judges, lawyers, psychiatrists, psychologists and experts working in the field of child protection. These experts have been trained in their professional capacity to provide independent and neutral advice. It was not a given that the Reporting Centre was accepted and seen to be providing a neutral intervention. Claimants, victim organisations and peer support groups had a preconceived idea that the Reporting Centre was an ‘agency of the Church’, despite the guarantees and meaningful reforms that had been instigated in accordance with the recommendations of Committee Deetman (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). For example, the public statement of the former Chairperson of the Complaints Committee shocked the Church (Dohmen, 2013), even though the statement was recognised as being truthful within ecclesiastical circles.

Classification and Analysis of the Response Procedures Note. *Complaint and compensation procedures, **Mediation procedures.

Note. *Complaint and compensation procedures, **Mediation procedures. The public statement underpinned the independence of the Reporting Centre (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). Neutrality was also reflected in the way the Reporting Centre, HEG Committee and Final Action were regulated. The Church wanted to set up its own response procedure, partly inspired by arbitration and aimed mainly at monetary compensation. The arbitration regulations were formalised procedures described in detail on paper. By creating Committee Lindenberghs’ monetary categories, the procedures were formalised with the intention of neutralising the procedure, allowing all claims to be measured using the same benchmark.

Trustworthiness emerges as an attribute central to the quality of decision making. Dimensions of trustworthiness are identified in the literature as competence/ability, integrity and benevolence (Haynes et al., 2012). Prior research found that competence in an individual depended on reputation, academic authority, scope of expert knowledge, applied research skills and communication skills (Haynes et al., 2012). The committee members were all experts with long, distinguished careers. These characteristics are expected to influence and enhance the quality of the decision making. The experts who were used were recognised as having ample experience in executing a fair judgment and in brokering trust. Although integrity and benevolence are difficult to assess in advance, we can only assume that the chosen experts would have these traits.

Respect is another attribute that influences the quality of decision making. Since the three complaint and compensation procedures were all put in place to ensure that the victim-survivors would receive recognition and repair, respect for the victim-survivors was paramount. Certain elements of respect, namely friendliness and opportunity to be heard, are more easily evaluated ex post, since it is difficult to state beforehand whether and in what ways the behaviour of authorities when dealing with claimants would align with these attributes.

Voice was omitted in the context of both the HEG Committee and Final Action, because there was no direct engagement or dialogue with claimants. In contrast, the Reporting Centre did have a dialogical element. Yet in most cases first-hand reporting by the perpetrator was not possible because they might be deceased or have physical or mental incompetence (Aertsen & Schotsmans, 2020). In these cases surrogate arrangements could still provide repair (Johnstone & Van Ness, 2007). It is not just the individual but also the Church as an institution that needs to be held accountable since ‘it has been reliant on the abuse of institutional power and resulted in direct emotional, psychological and spiritual harm to victims of abuse’ (Death, 2015: 94). The Reporting Centre was set up specifically for victim-survivors, but the opportunity for the Church itself to have an internal dialogue was missing.

We can conclude that the design and implementation of the Reporting Centre, HEG Committee and Final Action lacked certain procedural justice characteristics necessary for fulfilling their promise of providing recognition and repair. Certain procedural justice principles were applied in all three response procedures, albeit in varying degrees. The principle of neutrality, so necessary for the formalisation and regulation of all three procedures, was present in all procedures. Trustworthiness was also present in all procedures, specifically in relation to competence and ability. However, an ex ante evaluation of the concepts of integrity and benevolence proved difficult to assess. Although this is crucial to all three procedures, consideration for victim-survivors and for what served them best is better analysed ex post. Voice is included in the Reporting Centre and it proved to be central for repair, yet victim voice was omitted within both the HEG Committee and Final Action.6.2 Restorative justice: ‘Institutional’ mediation and Triptych mediation

From a restorative justice lens ‘institutional’ mediation and Triptych mediation share several similarities. Both are based on encounter, and more specifically on dialogue aimed at moving beyond antagonistic procedures (Bisschops, 2014; Goosen, 2016). As the former head of the Reporting Centre pointed out, both mediation approaches specifically consider non-cooperating defendants and defendants who were deceased, since the actual perpetrator was often absent.10x Telephone conversation with former head of the Reporting Centre (13 May 2022). This is opposed to ‘regular’ mediation, where the actual defendant is more often than not part of the process. Surrogate arrangements can prove to be restorative forms of engagement (Johnstone & Van Ness, 2007). Encounter was equally present in ‘institutional’ mediation and Triptych mediation. Both mediation procedures emphasised the importance of granting voice to claimants, acknowledging and facilitating conversation with Church representatives, allowing for questions and answers, providing explanations of the facts and consequences, respectful listening, discussion of the role of the Church, offering an apology and the possibility of a financial compensation.

The main difference between ‘institutional’ mediation and Triptych mediation is the involvement of the parties in the design of the procedures. Different parties coming together to meet each other encompass encounter (Johnstone & Van Ness, 2007). While encounter was ubiquitous with regard to Triptych mediation, it was only partly so within ‘institutional’ mediation. ‘Institutional’ mediation is contrary to a core principle of restorative justice, in that the relevant parties themselves take the initiative and have the freedom to organise the proceedings. Second, there is a demonstrable difference between the inception of both procedures. ‘Institutional’ mediation can be understood as being a top-down initiative, while Triptych mediation is essentially a bottom-up or grass-roots approach. Those who felt that contemporary justice procedures were inflexible and impersonal were attracted to the grassroots, bottom-up, informal practices that are often associated with restorative justice (Ward & Langlands, 2009).

‘Institutional’ mediation and Triptych mediation aimed at achieving recognition and repair through dialogue between the victim and the defendant or their legal representative. Repair not only focuses on the individual claimant or defendant or representative of the defendant but, more importantly, addresses the harm that needs to be repaired from a broader perspective, and this includes families, institutional parties and the community. Herein lies the frailty of both mediation procedures, since the schemes are focused solely on the primary victim and the offender. Family members, the institution and the community are not explicitly included in the design of those mediation procedures, and thus full repair is difficult to attain. Restorative justice is not about repair, encounter and adherence to procedural principles alone; it is also about involving claimants’ social network and the wider community in the procedures to deal with the ripple effects of harm.

The least recognisable in both procedures is the transformative factor. Elements of transformation might potentially arise at the level of the claimant and the defendant but less so at the level of institutions or society (Aertsen & Schotsmans, 2020). The notion of ‘all those affected’ within the mediation procedures was missing, since they were not designed to directly tackle institutional hegemony. Mediation procedures tended to focus on dialogue between actors at a micro level. There is thus a discrepancy between this specific type of restorative justice and one of the core characteristics of restorative justice, which is the transformative aspect.

In summary, in the design and implementation of ‘institutional’ mediation and Triptych mediation, restorative justice principles were applied. Encounter is present in both instances, but the level of claimants’ involvement in decision making is higher in Triptych mediation than in ‘institutional’ mediation. Repair was identified as the goal in both procedures, although it focused particularly on the victim and the offender. Institutional actors and the wider community were not included in the design of the procedures, making repair at the level of the involved institutions and society unattainable. It is thus clear that transformation is not a core feature in either of the procedures. Triptych mediation, because it is more bottom up, abides with the restorative justice approach in a way that ‘institutional’ mediation does not. Nevertheless, both mediation procedures failed to address the ripple effects of harm, and family members were subsequently omitted from the proceedings. -

7. Discussion

This article explored the response procedures in dealing with massive historical institutional abuse by the clergy in the Netherlands. We categorised the responses as institutional (the majority of the responses) and non-institutional procedures (one alternative procedure), which reflects on the leading role that the Church itself played in determining which instruments of recognition and repair would be provided. The lens of procedural and restorative justice was used to analyse the response procedures, enabling us to highlight some of the (im)possibilities of these procedures in offering what was promised, namely recognition and repair.

The analysis showed that, owing to the dominant role of the Church, the institutional element of the harm inflicted on the victim-survivor was on the whole avoided. For example, only the defendants (or their representatives), and none of the actors who constituted the broader structures of the Church, were given a platform within the initiated procedures. While key principles of procedural justice were applied in all three institutional response procedures, albeit in varying degrees, this still begs the question of who needs to be included in dialogue when aiming for full repair.

By reaching beyond an outcome-focused approach and by analysing the complaint and compensation procedures through a procedural justice framework, it was clear that the key elements – neutrality, trustworthiness (partly) and voice – were present in the Reporting Centre but not in HEG Committee and the Final Action. However, despite this, there was too little space for victims’ voice in both procedures. The procedural justice framework is able to show where complaint and compensation procedures are lacking. With regard to the design and implementation of ‘institutional’ mediation and Triptych mediation, restorative justice principles were applied at different levels. Encounter between victim and perpetrator was the most visible determinant of restorative justice in both procedures. Both mediation procedures suffered from crucial limitations. Repair and harm were dealt with too narrowly.

Our findings are similar to what has emerged in the literature, where many redress proceedings were adversarial, opaque, top-down and encouraged power imbalances (Courtin, 2015; Daly, 2018; Ellis & Ellis, 2014). Of the five procedures that were explored, four were top-down and therefore often opaque. Owing to various difficulties faced by the Reporting Centre, Triptych mediation was set up by victim-survivors. However, in the same way that Terry (2015) posits, we found Triptych mediation similarly promising, albeit with an important caveat. ‘All parties affected’ also includes family members, the institution and the community, none of which were included in the procedure.

In this article we have analysed the response procedures ex ante for the outcomes of recognition and repair. However, we must conclude that whether or not recognition and repair are obtained or forfeited, an ex post analyses of the response procedures, based on empirical data, is necessary.

While the abuse scandal resulted in public outrage, both institutional and non-institutional procedures offered no concrete responses for society. Despite the need for a far more systemic approach as a core element of a restorative approach to recognition and repair, the mediation procedures precluded this (Aertsen & Schotsmans, 2020; Johnstone & Van Ness, 2007). Our case study has shown that the restorative justice approach clarifies and displays the determinative nature of certain views, values and power relations in society. Clearly, from our analysis of the response procedures, what is neglected is not just the Church as an institution but also the family as an ‘institution’ (Bau & Fernández, 2022). Cases of abuse in Catholic institutions have been associated with severe family relationship breakdowns impacting on the identity of family and worldview, to say the least (Gavrielides, 2013), and, often, ironically, resulting in so-called secondary victimisation (Courtin, 2015). This remission is even more surprising given that the Church itself is considered by many to be a particular family. As such, claimants belong to two families. Surely, ignoring this ‘family’ aspect has an effect on procedures that are supposed to be reparatory? To explore this systemic aspect, our future research will engage with both the Church and the family as being spaces which allow for micro, meso and macro approaches to identify what a more comprehensive recognition or full repair, taking cognisance of a far more systemic approach, could look like.11x ‘Micro’ is the level of the individual victim-survivor, possibly the (alleged) perpetrator or a responsible person of the ‘accused’ institution; ‘meso’ is the level of the institute, because abuse was committed in institutions to which the offender is affiliated and usually in the context of a relationship of authority with regard to the minor; ‘macro’ is the level of society, institutional abuse is only possible in a society that provides, facilitates or tolerates its cultural and structural conditions (Aertsen & Schotsmans, 2020). Thus, ex post analyses of the response procedures should focus on claimants, but also on their family and the Church as an institution. We hypothesise that since harm is systemic, repair should be systemic as well. To test this hypothesis, research on the expectations and the experiences of claimants with the redress procedures, the (possible) presence of ripple effects for their next of kin and how institutional accountability for the abuse is ensured within Dutch Catholic institutions is vital.

The preclusion of a systemic approach has been identified by Immler (2020), who shows that while repair policy is, at first glance, about the dialogue between opposing parties, it is also about the dialogue within families and communities. Repair is often inadequate. Responsibility for recovery is focused on the individual, and too often the social relationships within which individuals could recover (family, institutions, community) are disregarded. It is necessary to pay more attention to this relational perspective and also to the institutions that determine which response procedures are applied and which are withheld (Immler, 2020). Our research shows that the procedures established by both the Church and victim-survivors themselves have not yielded the anticipated dialogue within the institution and society and, consequently, as they are not allowing for the completion of a cycle of recognition and repair, are limiting the potential of these procedures to repair.

While none of the response procedures are still in use, the Church made arrangements for victim-survivors to report ‘new’ complaints – which are not time barred – of transgressional behaviour by clergy members. On 1 May 2015, the Bishops Conference and the Conference of Dutch Religious established a Reporting Centre for Transgressional Behaviour. Here, new cases of child abuse can be reported to the police (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). This illustrates that the Church is aware that abuse cases continuously need to be brought to attention, although it is not clear whether this will bring about institutional change. However, one way in which institutional responsibility could be more efficiently addressed would be through civil court cases. Ongoing civil court cases in the Netherlands against institutions of the Church seem to be promising and to show that this legal approach has some value and could ‘force’ the Church as an institution to take responsibility.12x Two court cases concerning (sexual) abuse in Congregations: (1) the Congregation of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (Civil Chamber, 15 July 2015, ECLI:NL:RBZWB:2015:4615), (2) the Congregation of the Holy Spirit (Civil Chamber, 16 January 2019, ECLI:NL:RBLIM:2019:235). Moreover, there is an ongoing lawsuit regarding forced labour in the Congregation of the Good Shepherd (Civil Chamber, 13 October 2021, ECLI:NL:RBNHO:2021:8863). All claimants of these court cases first made use of the response procedures. Their dissatisfaction with the narrowness of the procedures and their inability to address the institutional level was a driver for filing a claim in court. This suggests that the ‘status’ of court cases begs further investigation to determine whether and in what way the court route might add extra value in the search for recognition and repair, by upholding civil court cases to the ‘yardstick’ of both procedural and restorative justice elements as we have analysed them. Following up on a historical study by several prominent procedural justice scholars, we explore the reactions and experiences of tort litigants in personal injury cases whose cases had been resolved by trial or procedures falling between tort litigation, arbitration and compensation, by means of procedural aspects (Lind et al., 1990). Regarding restorative justice, we will also investigate whether individual harm is being acknowledged and whether there are by-products of such court case. Perhaps civil court cases – especially if the media is involved – can start societal conversations about the responsibility of the Church for the victims it has claimed. References Adriaenssens, P., Bernaert, F., Bastin, M., Decock, C., Degrieck, P., Demasure, K., de Montpellier, N., Fortemps, E., Hainaut, H., Hayen, L., Jansen, A., Journeé, M., Martens, K., Schouppe, J. & van Grembergen, R. (2010). Verslag activiteiten commissie voor de behandeling van klachten wegens seksueel misbruik in een pastorale relatie. Leuven: Commissie voor de behandeling van klachten wegens seksueel misbruik in een pastorale relatie.

Aertsen, I. & Schotsmans, M. (2020). Institutioneel misbruik en geweld uit het verleden: een vergelijking van twee herstelgerichte responsmodellen in België. Tijdschrift voor Herstelrecht, 20(3), 9-36. doi: 10.5553/TvH/1568654X2020020003003.

Balboni, J.M. & Bishop, D.M. (2010). Transformative justice: survivor perspectives on clergy sexual abuse litigation. Contemporary Justice Review, 13(2), 133-154, doi: 10.1080/10282580903549086.

Bau, N. & Fernández, R. (2022). Culture and the family. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. w28918. Retrieved from www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28918/w28918.pdf (last accessed 12 February 2024).

Belgische Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers (2017, March 6). Eindverslag van het Wetenschappelijk Comité van het Centrum voor Arbitrage inzake Seksueel Misbruik, Parlementaire Staten, Kamer, 2016-2017, nr. 0767/004.

Bisschops, A. (2014). De klachtenafhandeling van seksueel kindermisbruik in de Katholieke kerk: een vergelijking van drie procedures. Unpublished manuscript.

Blader, S.L. & Tyler, T.R. (2003). A four-component model of procedural justice: defining the meaning of a “fair” process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(6), 747-758. doi: 10.1177/0146167203029006007.

Brockner, J., Ackerman, G., Greenberg, J., Gelfand, M.J., Francesco, A.M., Chen, Z.X., Leung, K., Bierbrauer, G., Gomez, C., Kirkman, B.L. & Shapiro, D. (2001). Culture and procedural justice: the influence of power distance on reactions to voice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37(4), 300-315. doi: 10.1006/jesp.2000.1451.

Chatelion Counet, P. (2020). De Deetman files: misstanden rond het kindermisbruik. Almere: Uitgeverij Parthenon.

Courtin, J. (2015). Sexual assault and the Catholic church: are victims finding justice? (PhD Dissertation). Monash University, Australia.

Daly, K. (2018). Inequalities of redress: Australia’s national redress scheme for institutional abuse of children. Journal of Australian Studies, 42(2), 204-216. doi: 10.1080/14443058.2018.1459783.

De Mesmaecker, V. (2011). Perceptions of justice and fairness in criminal proceedings and restorative encounters: extending theories of procedural justice (PhD Dissertation). Catholic University Leuven, Belgium.

Death, J. (2015). Bad apples, bad barrel: exploring institutional responses to child sexual abuse by Catholic clergy in Australia. International Journal for Crime, 4(2), 94-110. doi: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v4i2.229.

Deetman, W. (2013). Seksueel misbruik van en geweld tegen meisjes in de rooms-katholieke kerk: een vervolgonderzoek. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Balans.

Deetman, W., Draijer, P., Kalbfleisch, P., Merckelbach, H., Monteiro, M., de Vries, G. & Kreemers, H. (2010). Naar hulp, genoegdoening, openbaarheid en transparantie: een onderzoek naar en advies over het functioneren van de kerkelijke instelling voor hulp aan en recht voor slachtoffers van seksueel misbruik in de Rooms-Katholieke Kerk in Nederland. Commissie van onderzoek seksueel misbruik in de Rooms- Katholieke Kerk. Retrieved from www.rkkerk.nl/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/2010_10-Commissie-Deetman-rapport-en-persberichten.pdf (last accessed 8 December 2022).

Deetman, W., Draijer, N., Kalbfleisch, P., Merkelbach, H., Monteiro, M.E. & De Vries, G. (2011). Seksueel misbruik van minderjarigen in de Rooms-Katholieke kerk. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Balans.

Dohmen, J. (2010, February 26). Nederlandse paters beticht van seksueel misbruik. Retrieved from www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2010/02/26/nederlandse-paters-beticht-van-seksueel-misbruik-11856255-a1161451 (last accessed 12 October 2022).

Dohmen, J. (2013, February 23). Kindermisbruik kost Rooms-Katholieke kerk 30 miljoen euro. Retrieved from www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2013/02/23/kindermisbruik-kost-rooms-katholieke-kerk-30-miljoen-euro-a1437006 (last accessed 12 October 2022).

Ellis, J. & Ellis, N. (2014). A new model for seeking meaningful redress for victims of church-related sexual assault. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 26(1), 31-41. doi: 10.1080/10345329.2014.12036005.

European Forum for Restorative Justice (2021). Manual on restorative justice values and standards for practice. Retrieved from www.euforumrj.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/EFRJ_Manual_on_Restorative_Justice_Values_and_Standards_for_Practice.pdf (last accessed 19 January 2022).

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2014). Victims of crime in the EU: the extent and nature of support for victims. Retrieved from https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra-2015-victims-crime-eu-support_en_0.pdf (last accessed 19 January 2022).

Faget, J. (1997). La mediation pénale. Essaie de politique pénale. Toulouse: Erès.

Fogler, J.M., Shipherd, J.C., Rowe, E., Jensen, J. & Clarke, S. (2008). A theoretical foundation for understanding clergy-perpetrated sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 17(3-4), 301-328. doi: 10.1080/10538710802329874.

Gallen, J. (2016). Jesus wept: the Roman Catholic Church, child sexual abuse and transitional justice. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 10(2), 332-349. doi: 10.1093/ijtj/ijw003.

Gavrielides, T. (2013). Clergy child sexual abuse and the restorative justice dialogue. Journal of Church and State, 55(4), 617-639. doi: 10.1093/jcs/css041.

Goosen, C. (2016). Herstelbemiddeling over seksueel misbruik in de Katholieke kerk. Conflicthantering, 5(6), 29-34.

Haynes, A.S., Derrick, G.E., Redman, S., Hall, W.D., Gillespie, J.A., Chapman, S. & Sturk, H. (2012). Identifying trustworthy experts: how do policymakers find and assess public health researchers worth consulting or collaborating with? PloS One, 7(3), e32665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032665.

Houppermans, M. (2011). De hausse aan meldingen. Een achtergrondstudie over de hausse aan meldingen vanaf februari 2010 over seksueel misbruik binnen de Rooms-Katholieke Kerk en de rol van de media. In W. Deetman (ed.), Seksueel misbruik van minderjarigen in de rooms-katholieke kerk. Vol. 2: De achtergrondstudies en essays (pp. 192-217). Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Balans.

Hoyle, C. & Batchelor, D. (2018). Making room for procedural justice in restorative justice theory. The International Journal of Restorative Justice, 1(2), 175-186. doi: 10.5553/IJRJ/258908912018001002001.

Huelin, R., Iheanacho, I., Payne, K. & Sandman, K. (2015). What’s in a name? Systematic and non-systematic literature reviews, and why the distinction matters. The Evidence Forum. Retrieved from www.evidera.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Whats-in-a-Name-Systematic-and-Non-Systematic-Literature-Reviews-and-Why-the-Distinction-Matters.pdf (last accessed 24 February 2024).

Immler, N. (2020). Erkenning: het herstel van sociale relaties. Impact Magazine, ARQ Nationaal Psychotrauma Centrum, 4, 5-7.

Immler, N. (2022). De (Dia)Logics van Erkenning en Herstel (Inaugural lecture). University of Humanistic Studies, the Netherlands.

Johnstone, G. & Van Ness, D.W. (2007). Handbook of restorative justice. London: Willan Publishing.

Klijn, L.P.M. (2015). Drieluikherstelbemiddeling bij seksueel misbruik, een symbiose van erkenning en financiële genoegdoening. Tijdschrift voor Vergoeding Personenschade, 4, 97-106. doi: 10.5553/TVP/138820662015018004002.

KNR. (2015). Preventie van seksueel misbruik en grensoverschrijdend gedrag binnen de Rooms-Katholieke Kerk en aanpak herstel, erkenning en genoegdoening. Retrieved from www.rkkerk.nl/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/2015-10-23-RAPPORTAGE-2010-2015_september2015.pdf (last accessed 16 September 2022).

Kudlac, K.E. (2006). Family narratives of crisis and strength: a phenomenological study of the effects on the family system when a child has been sexually abused by a Catholic priest (PhD Dissertation). Texas Woman’s University, United States.

Lau, J.D., Gurney, G.G. & Cinner, J. (2021). Environmental justice in coastal systems: perspectives from communities confronting change. Global Environmental Change, 66, 102208. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102208.

Lecuyer, L., White, R.M., Schmook, B., Lemay, V. & Calmé, S. (2018). The construction of feelings of justice in environmental management: an empirical study of multiple biodiversity conflicts in Calakmul. Journal of Environmental Management, 2(13), 363-373. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.02.050.

Lind, E.A., MacCoun, R.J., Ebener, P.A., Felstiner, W.L., Hensler, D.R., Resnik, J. & Tyler, T.R. (1990). In the eye of the beholder: tort litigants’ evaluations of their experiences in the civil justice system. Law and Society Review, 24(4), 953-996. doi: 10.2307/3053616.

Ludwin King, E.B. (2017). Transitional justice and the legacy of child sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. Albany Law Review, 81(1), 121-144.

MacCoun, R.J. (2005). Voice, control, and belonging: the double-edged sword of procedural fairness. The Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 1, 171-201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.1.041604.115958

Marotta, G. (2021). Child sexual abuse by members of the Catholic Church in Italy and France: a literature review of the last two decades. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 30(8), 911-931. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2021.1955790.

Matthews, T. (2015). Evaluating Towards Healing as an alternative to litigation as redress for survivors of clerical child sexual abuse. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 26(3), 333-340. doi: 10.1080/10345329.2015.12036025.

McAlinden, A. & Naylor, B. (2016). Reframing public inquiries as ‘procedural justice’ for victims of institutional child abuse: towards a hybrid model of justice. The Sydney Law Review, 38(3), 277-309.

McGraw, D.M., Ebadi, M., Dalenberg, C., Wu, V., Naish, B. & Nunez, L. (2019). Consequences of abuse by religious authorities: a review. Traumatology, 25(4), 242-255. doi: 10.1037/trm0000183.

Milquet, J. (2019). For a new EU Victims’ rights strategy 2020-2025. Strengthening victims’ rights: from compensation to reparation. European Commission. Retrieved from https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/0184a9c1-09ae-4773-a42a-7107238ddbbd_en?filename=strengthening_victims_rights_-_from_compensation_to_reparation_rev.pdf (last accessed 12 February 2024).

Mulder, J. (2013). Compensation: the victim’s perspective (PhD Dissertation). Tilburg University, the Netherlands.

Noll, D.E. & Harvey, L. (2008). Restorative mediation: the application of restorative justice practice and philosophy to clergy sexual abuse cases. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 17(3-4), 377-396. doi: 10.1080/10538710802330021.

Pemberton, A., Aarten, P.G.M. & Mulder, E. (2017). Beyond retribution, restoration and procedural justice: the Big Two of communion and agency in victims’ perspectives on justice. Psychology, Crime & Law, 23(7), 682-698, doi: 10.1080/1068316X.2017.1298760

Restorative Justice Exchange (n.d.). Three core elements of restorative justice. Retrieved from https://restorativejustice.org/what-is-restorative-justice/three-core-elements-of-restorative-justice/ (last accessed 20 May 2022).

Rottman, D.B. (2007). Adhere to procedural fairness in the justice system. Criminology and Public Policy, 6(4), 835-842.

Ruano-Chamorro, C., Gurney, G.G. & Cinner, J.E. (2022). Advancing procedural justice in conservation. Conservation Letters, 15(3), 1-12. doi: 10.1111/conl.12861.

Sanders, L. & Spekman, B. (2018). Reporting centre sexual abuse within the Roman Catholic Church in the Netherlands. Management and Monitoring Foundation on Sexual Abuse within the Roman Catholic Church in the Netherlands.

Spröber, N., Schneider, T., Rassenhofer, M., Seitz, A., Liebhardt, H., König, L. & Fegert, J.M. (2014). Child sexual abuse in religiously affiliated and secular institutions: a retrospective descriptive analysis of data provided by victims in a government-sponsored reappraisal program in Germany. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1-12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-282.

Tamarit, J., Aizpitarte, A. & Arantegui, L. (2021). Child sexual abuse in religious institutions: a comparative study based on sentences in Spain. European Journal of Criminology, 20(1), 1-14. doi: 10.1177/1477370820988830.

Tamarit, J., Padró-Solanet, A., Guardiola, M.J. & Hernández, P. (2017). Estudios de sentencias: las decisiones judiciales en los casos de victimización sexual de menores. In J. Tamarit (ed.), La victimización sexual de menores de edad y la respuesta del sistema de justicia penal (pp. 97-167). Montevideo-Buenos Aires: BdeF-Edisofer.

Terry, K.J. (2008). Stained glass: the nature and scope of child sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35(5), 549-569. doi: 10.1177/0093854808314339.

Terry, K.J. (2015). Child sexual abuse within the Catholic church: a review of global perspectives. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 39(2), 139-154. doi: 10.1080/01924036.2015.1012703.

Tyler, T.R. (2000). Social justice: outcome and procedure. International Journal of Psychology, 35(2), 117-125. doi: 10.1080/002075900399411.

UNODC (2020). Handbook on Restorative Justice Programmes (2nd ed.). United Nations.

Van Camp, T. & Wemmers, J. (2013). Victim satisfaction with restorative justice. International Review of Victimology, 19(2), 117-143. doi: 10.1177/0269758012472764.

Van Dijck, G. (2018). Victim oriented tort law in action: an empirical examination of Catholic church sexual abuse cases. SSRN Electronic Journal, 15(1), 126-164. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2738633.

Van Rij, C. (2017). Erkenning, genoegdoening of opnieuw geraakt: ervaringen met de financiële regelingen ‘Seksueel misbruik in instellingen en pleeggezinnen. Cebeon-Centrum Beleidsadviserend Onderzoek. Retrieved from https://repository.wodc.nl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12832/2278/2713_Volledige_Tekst_tcm28-259582.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y (last accessed 12 February 2024).

Van Wormer, K. & Berns, L. (2004). The impact of priest sexual abuse: female survivors’ narratives. Affilia, 19(1), 53-67. doi: 10.1177/0886109903260667.

Verhoeven, P. & Aertsen, I. (2017). Het Centrum voor Arbitrage inzake seksueel misbruik: what’s in a name? Panopticon, 38(6), 482-491.

Verschuuren, J. & van Gestel, R. (2009). Ex ante evaluation of legislation: an introduction. In J.M. Verschuuren (ed.), The impact of legislation: a critical analysis of ex ante evaluation (pp. 3-10). Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Ward, T. & Langlands, R. (2009). Repairing the rupture: restorative justice and the rehabilitation of offenders. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(3), 205-214. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2009.03.001.

Wemmers, J.M. (1996). Victims in the criminal justice system (PhD Dissertation). Leiden University, the Netherlands.

Wind, L.H., Sullivan, J.M. & Levins, D.J. (2008). Survivors’ perspectives on the impact of clergy sexual abuse on families of origin. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 17(3-4), 238-254, doi: 10.1080/10538710802329734.

Zehr, H. (2004). Commentary: restorative justice: beyond victim-offender mediation. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 22(1-2), 305-315. doi: 10.1002/crq.103.

Zehr, H. & Mika, H. (1998). Fundamental concepts of restorative justice. Contemporary Justice Review, 1(1), 47-55.

Jurisprudence Civil Chamber, 1 October 2014, ECLI:NL:RBMNE:2014:4604.

Civil Chamber, 15 July 2015, ECLI:NL:RBZWB:2015:4615.

Civil Chamber, 16 January 2019, ECLI:NL:RBLIM:2019:235.

Civil Chamber, 13 October 2021, ECLI:NL:RBNHO:2021:8863.

Noten

-

1 ‘Institutional’ – in this context – refers to the institution of the Church and concretely refers to response mechanisms that have been initiated by the Church. ‘Non-institutional’ refers to the response mechanism that has been initiated by victim-survivors themselves, thus without the assistance of an institution.

-

2 When describing the response procedures, we use the term ‘claimant’ instead of ‘victim-survivor’. Here, we chose to use the juridical term, since it concerns regulated response procedures.

-

3 In March 2010, former MP Wim Deetman became the Chair of this Committee, and he was asked by the Bishops’ Conference and the Conference of the Dutch Religious to conduct an independent inquiry into sexual abuse in Dutch Catholic institutions (Sanders & Spekman, 2018). All bishops in the Dutch Ecclesiastical Province form the Bishops’ Conference of the Netherlands, a permanent consultative body, in which the bishops jointly formulate and implement policy in various fields. The Bishops’ Conference members comprise seven resident bishops, their auxiliary bishops and titular bishops who fulfil a function in the Dutch ecclesiastical province (www.rkkerk.nl/kerk/kerkprovincie/bisschoppenconferentie/). The Conference of Dutch Religious is the umbrella organisation of (almost) all religious orders and congregations in the Netherlands. It represents the interests of friars, nuns and brothers and encourages cooperation between various monasteries (www.knr.nl/over-knr/wie-zijn-wij/).

-

4 Interview with former head of the Reporting Centre (21 January 2022).

-

5 Interview with the former Chairperson of the Compensation Committee (21 December 2021).

-

6 Telephone conversation with former head of the Reporting Centre (13 May 2022).

-

7 Civil Chamber, 1 October 2014, ECLI:NL:RBMNE:2014:4604.

-

8 Interview with legal secretary/confidential advisor Triptych mediation (14 January 2022).

-

9 To clarify, in Figure 1, we categorised ‘institutional’ mediation under track I since it is a response procedure instigated by the Church. However, we analysed ‘institutional’ mediation with a restorative justice lens, and it therefore falls under track II.

-

10 Telephone conversation with former head of the Reporting Centre (13 May 2022).

-

11 ‘Micro’ is the level of the individual victim-survivor, possibly the (alleged) perpetrator or a responsible person of the ‘accused’ institution; ‘meso’ is the level of the institute, because abuse was committed in institutions to which the offender is affiliated and usually in the context of a relationship of authority with regard to the minor; ‘macro’ is the level of society, institutional abuse is only possible in a society that provides, facilitates or tolerates its cultural and structural conditions (Aertsen & Schotsmans, 2020).

-

12 Two court cases concerning (sexual) abuse in Congregations: (1) the Congregation of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (Civil Chamber, 15 July 2015, ECLI:NL:RBZWB:2015:4615), (2) the Congregation of the Holy Spirit (Civil Chamber, 16 January 2019, ECLI:NL:RBLIM:2019:235). Moreover, there is an ongoing lawsuit regarding forced labour in the Congregation of the Good Shepherd (Civil Chamber, 13 October 2021, ECLI:NL:RBNHO:2021:8863).