Reconciliation potential of Rwandans convicted of genocide

-

1. Introduction

1.1 The Rwandan genocide

The small, landlocked country of Rwanda has experienced several devastating waves of mass killing since 1959; however the country rose to world attention in the wake of the 1994 genocide. Beginning April 7th, following the assassination of Rwanda’s President Juvénal Habyarimana and Burundi’s President Cyprien Ntaryamira, and lasting for 100 days, the ‘genocidal juggernaut’ (Taylor, 1999: 182) between Hutus and Tutsis claimed the lives of between 500,000 (Des Forges, 1999) to over a million Rwandans (Reyntjens, 2004), and created more than one million refugees (Purdeková, 2015). The Rwandan genocide involved high levels of ‘popular participation’ (Waldorf, 2006a: 7), with estimates of the number of perpetrators involved in the Rwandan genocide ranging from 200,000 (Straus, 2004) to more than a million (Cobban, 2002). The perpetrators systematically targeted Tutsis, a minority group considered the elite in Rwandan society and estimated to be just 14 per cent of the population (Staub, Pearlman, Gubin & Hagengimana, 2005). During 100 days in 1994, over 10 per cent of the Rwandan population was killed (Schaal, Weierstall, Dusingizemungu & Elbert, 2012), with the victims comprised of Tutsis and moderate Hutus. Overall, a staggering 75 per cent of the Tutsi population were massacred (Des Forges, 1999).

Exacerbating existing notions of difference, colonial governments in Rwanda promoted conceptions of racial differentiation and essentialisation (Mamdani, 2001). Based on the false belief that Tutsis were descendants from Noah’s son Ham, and therefore essentially white European, colonists constructed Tutsis as the ‘great civilizers’ (Mamdani, 2001: 86) in the African continent, bestowing a pseudo-minority with privilege. In post-colonial Rwanda, such pro-Tutsi ideology was reversed, with Tutsis regarded as ‘degenerate and demonic’ (Rothbart & Bartlett, 2008: 227). The civil war began in 1990 following incursions by the Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF), an assemblage of Tutsi militias in Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi and Zaire; and comprised largely of the children of exiled Tutsi refugees (Staub et al., 2005). The RPF incursions fuelled the perception that Tutsis were ‘invaders from the north’ (Taylor, 1999), ‘inyenzi’ (cockroaches), and a threat to Rwandan society. Encouraged by incessant government influenced radio and newspaper propaganda, and political consolidation of the Hutu Power ideology, the local population was urged to exterminate the Tutsi.

According to McDoom (2013), the genocidal crimes were not committed by highly trained professionals, but rather the perpetrators included fairly ordinary people such as soldiers, militia, policemen and farmers drawn largely from the Hutu population. Knives, machetes and nail-studded clubs were commonly wielded in the genocide. The genocidal killings involved neighbours and family members who targeted each other. In that sense, this was not similar to any other genocide in modern human history. Such an intimate genocide (Staub & Pearlman, 2001) included the rape of more than 350,000 women and girls (Bijleveld, Morssinkhof & Smeulers, 2009).

More than 20 years later, Rwandan society is still in the process of healing, trying to bridge deeply fragmented segments of Rwandan society. In post-genocide Rwanda the crimes of ‘divisionism’ and ‘promoting genocide ideology’ has curtailed the widespread use of artificial ethnic categories such as Hutu or Tutsi. New categories of survivor, victim and (international) bystander have emerged as the country works towards unity. Subsequently, the Tutsi government, that regained control over Rwanda, has heavily promoted the idea of unity through healing and reconciliation among all Rwandese. It is within this context that the present study examines the reconciliation potential of those perpetrators convicted of genocide. Specifically, previous studies have attempted to examine reconciliation by looking at those victimised during the genocide. However, less attention has been given to the genocide perpetrators who were sentenced and are expected to re-enter Rwandan society in the next few years. The current study addresses this gap in understanding by examining the physical and mental health needs of incarcerated Rwandan genocide perpetrators, and the relationships between such needs, posttraumatic stress disorder and attitudes desirous of reconciliation and unity. The study is the baseline data collection and analysis of the PeaceBuilder Project, a project that uses an intervention model of council process (also called Peace Circles) and neuroscience-based self-regulation skills called the Social Resilience Model (SRM) to encourage listening and speaking from the heart, engender healing processes and build greater understanding and prosocial behaviours across difference. The Social Resilience Model potentially contributes to improved emotional and physical health outcomes in individuals who have experienced traumatic events. It is within this context that the current study aims to examine the potential and readiness of those convicted of genocide to processes of reconciliation and reintegration. -

2. Literature review

2.1 Meaningful reconciliation

As a country seeks to recover from the catastrophic trauma of genocide or mass killing, reconciliation is invariably regarded as an essential, albeit challenging, prerequisite (Sarkin & Daly, 2004). Reconciliation is often regarded as the panacea in post-genocidal and post-conflict settings, despite a sparsity of empirical data relating to the process (Meierhenrich, 2014). There is a need for deeply divided opposing groups to ‘reconcile’, thereby ending cycles of extreme violence, hatred and mistrust. Meaningful reconciliation can help prevent future violence and promote present day peace making through education and dialogue (Staub, 2006).

Although considerable ambiguity surrounds the term ‘reconciliation’ (Parent, 2010), reconciliation can be understood as a process that seeks to reduce and eventually ameliorate feelings of resentment between opposing individuals (Kinzer, 2014). Similarly, Galtung (2001: 3) suggests that reconciliation is ‘the process of healing the traumas of both victims and perpetrators after violence, providing a closure of the bad relations’. Meierhenrich (2008: 206) stresses the mutuality inherent in reconciliation when he suggests that ‘reconciliation refers to the accommodation of former adversaries through mutually conciliatory means, requiring both forgiveness and mercy’. Unfortunately, being merciful and forgiving can be an insurmountable task. Inter-group resentments and hostilities often intensify and solidify over years, if not generations. The next generation is bequeathed historical traumas of past wrongs, often ensuring the inter-generational transmission of hurt. Past traumas may be shared and transmitted as ‘chosen traumas’ (Volkan, 2001: 88), which in turn become woven into individual and group identities. When identification and rejection of the outside ‘other’ (Becker, 1963; Young, 1999) is a cornerstone of individual and group identity, chosen traumas may serve to concretise group difference and distance. Both groups may engage in ‘competitive victimhood’ (Noor, Brown, Gonzalez, Manzi & Lewis, 2008), believing that their respective group experienced more trauma than the opposing group. Staub et al. (2005: 301) suggest that full reconciliation ‘involves some degree or form of forgiving, letting go of the past, of anger and the desire for revenge’. A reconciliation process that involves the amelioration of such deep-seated resentment requires a shared commitment by former antagonists to work towards beginning ‘to hold a more positive orientation toward the other’ (Staub, 2006: 877) from which ‘mutual acceptance’ (Staub et al., 2005: 301) can develop.

In understanding the potential for reconciliation, examining and working through thoughts and emotions may not be enough. Traumatic experiences are held in the body and, as van der Kolk (2014: 66) emphasises, ‘are split off and fragmented so that the emotions, sounds, images, thoughts, and physical sensations related to the trauma take on a life of their own’. Gaining mastery over physiological sensations and corresponding emotions may be an essential aspect of increasing the readiness for reconciliation. The rippling impact of the various aspects of traumatic experience can be understood as a ‘splinter that causes an infection, it is the body’s response to the foreign object that becomes the problem more than the object itself’ (van der Kolk, 2014: 247).2.2 Mutuality and forgiveness

Mutuality is central to the reconciliation process, with both parties working to restore trust ‘through mutually trustworthy behaviours’ (Worthington & Drinkard, 2000: 93). Such a reconciliation process, as Clark (2010) notes, necessitates the ‘reshaping’ of relationships, as both groups seek to nurture nonviolent relations towards each other through ‘meaningful interaction and cooperation’ (Clark, 2010: 44). Forgiveness, although a desirable element of the reconciliation process (Staub & Pearlman, 2001), is not synonymous with reconciliation, as forgiveness does not require mutuality. Certainly, forgiveness often follows an apology or expression of remorse. However, forgiveness can and does occur in the absence of the perpetrator taking responsibility or seeking atonement. Immediately after the Charleston Church shooting in the U.S. state of Virginia, some family members of victims publicly forgave and prayed for the perpetrator. Although some may argue that such acts of forgiveness are less about transforming relations and are more indicative of individual character (Daly & Sarkin, 2007), others would suggest that personal acts of forgiveness can be a powerful tool facilitating individual healing (Kalayjian & Paloutzian, 2009). Forgiveness, many scholars argue, is a universal value promoted by every major religion (Zellerer, 2013). Given that it is unfair to expect victims, particularly victims of serious crimes such as sexual assault, murder and genocide, to immediately forgive, forgiveness in the restorative justice process may be considered more a ‘performative action’ (Dzur & Wertheimer, 2002: 12) or ritual (Braithwaite, 2002), rather than a psychological process. True forgiveness, as Braithwaite (2002: 15) suggests, is ‘a gift that victims can give’ or withhold. Certainly, President Kagame (2019) acknowledges the additional burden he is placing on genocide survivors when he urges them to forgive, however he comments that they are ‘the only ones with something left to give’ (cited in Jere, 2019).

2.3 Acknowledgment and apology

For perpetrators, apology may be an important step towards signifying acknowledgement of the harm they have caused and a step towards mutual reconciliation. In Rwanda, the Gacaca process was an important step towards acknowledgement, allowing a unique and specific ‘surfacing of the truth’ (Carter, 2007: 509). The Gacaca process, meaning ‘justice in the grass’ was a community justice court system in over 10,000 localities (Waldorf, 2006b) where community members described experiences during the genocide, generated a ‘collective truth’, and held perpetrators accountable. Gacaca is a traditional Rwandan method of dispute resolution typically used to resolve less serious disputes (Waldorf, 2006b). Rwanda’s post-genocide Gacaca courts can be considered a combination of restorative justice and retributive justice (Lambourne, 2016). Just under two million genocide cases were heard, and 130,000 perpetrators were incarcerated as a result of Gacaca processes (Nyseth-Brehm, Uggen & Gasanabo, 2014).

Apologies, when coupled with the act of forgiveness, have the potential to interrupt historical cycles of violence and conflict (Daly & Sarkin, 2007). Apologies signify a shift in the power-humiliation dynamic between the perpetrator and victim or survivor (Lazare, 2004). Apology is often an important component of restorative justice programmes, often given through letters to the victim, or public statements during victim-perpetrator conferences. Such ‘rituals of apology and forgiveness’ (van Stokkom, 2008: 402) are ways for perpetrators to recognise that what happened was inherently wrong. Apology engenders a shift in opposing dynamics, enabling perpetrators to disassociate from the offense, signifying that the perpetrator is committed, at least in principle, to ‘the offended(’s) rule’ (Goffman, 1971: 113). Of course, apologies may be sincere or feigned, and thus can be both appealing and profoundly unsatisfying for victims and survivors (Daly & Sarkin, 2007). Judging the sincerity of an apology, however, is a fruitless task and risks reinforcing disassociation between the perpetrator and victim. Although a sincere apology is the most desirable starting point for reconciliation, Tutu (1999: 272) observes that by waiting for a perpetrator’s apology we risk disempowering victims:If the victim could forgive only when the culprit confessed, then the victim would be locked into the culprit’s whim, locked into victimhood, whatever her own attitude or intention. That would be palpably unjust.

Release from continued disempowerment, Tutu (1999) suggests, can emerge when survivors make the gift of forgiveness available, giving the perpetrator the opportunity to appropriate the gift by acknowledging the wrongness of his or her actions. For many survivors of genocide and mass conflict, the physical and emotional wounds they carry are gargantuan. As Staub (2015) observes: ‘Their perception of themselves and the world is deeply affected. They feel diminished, vulnerable. The world looks dangerous and people, especially those outside one’s group, untrustworthy’ (Staub, 2015: 186). To hear the perpetrator acknowledge the wrongness of his or her actions and to demonstrate awareness of the harm caused signifies a critical repositioning of the survivor-perpetrator dyad. Such repositioning sets the conditions for mutual reconciliation, as both survivor and perpetrator are afforded the potential to recognise their shared humanity.

The act of apology was given an important role in post-genocide Rwanda. In the Gacaca courts a public apology was necessary if a perpetrators confession was to be accepted and his or her sentence reduced (Ingelaere, 2008). Although possibly more performative than deeply held, the apology marks a shift in power dynamics, and a starting point for deeper healing. The question of what it takes to generate as well as to receive a sincere acknowledgement of wrongdoing is an important one. The body can be trapped in the undigested traumatic energy, making an individual numb or irritable. The arrival of somatic-based research and intervention has offered new possibilities for healing from memories that have been ‘deeply engraved in the mind’ by stress chemicals (van der Kolk, 2014: 67).2.4 Healing trauma

Although acknowledgment of harm is an important step in the reconciliation process, many perpetrators will minimise the harm of their actions and continue to blame and dehumanise victims after genocide and mass violence (Staub & Pearlman, 2001). Such a stance may stem from perceived historical wrongs, unaddressed grievances, ‘unhealed psychological wounds’ (Staub, 2015: 187), undigested trauma stored as physiological reactivity (Scaer, 2005), and the narratives of dehumanisation promulgated by the political machinery of genocide. Scaer points out that management of a population by discrimination and fear constitutes a way of ‘maintaining cultural control through inflicting traumatic stress’ (2005: 6). Often, as Meierhenrich (2008: 207) observes, the line between the wronged and the wrongdoer is difficult to draw ‘for all sides have committed wrongs’. Furthermore, perpetrators may blame victims in order to avoid potential ontological distress, guilt and shame caused by facing up to the depravity of their crimes. For meaningful reconciliation to occur there is clearly a need for both parties to heal. As Staub (2006: 871) observes:

Without healing, when there is new group conflict, it will be difficult for them to consider the needs of the other and to trust the other, and thereby to resolve conflict peacefully.

Further, trauma may also inhibit the development of positive relations (Ronel & Elisha, 2011) between both survivors and perpetrators.

A central message here is that for reconciliation to occur, perpetrators need healing too. Such healing may be achieved through the employment of various coping skills which help in developing personal and social resources referred to as posttraumatic growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Perpetrators who have engaged in killing and mass violence may experience trauma as a result of their actions. DSM-V identifies that people may be exposed to traumatic events in four ways: through direct exposure, including being forced to commit violence, through witnessing the trauma, through learning that a relative or close friend was exposed to trauma, or through indirect exposure to traumatic details (vicarious trauma) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The diagnostic manual also provides examples of traumatic events, including (but not limited to) exposure to war as a combatant or civilian, threatened or actual physical or sexual violence, being kidnapped, taken hostage, terrorist attack and torture. Perpetrators of genocide and mass violence witness the traumatic event as they perpetrate it. Some kill because they are told they will be killed if they do not kill. Certainly, given the intimate nature of the killing, mutilation and torture that occurred during the Rwandan genocide, the trauma experienced by perpetrators is palpable.

Some who have experienced traumatic events, as perpetrator, victim or bystander may develop symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). PTSD is commonly recognised as persistent re-experiencing of the event, avoidance of trauma stimuli, negative thoughts and feelings, and arousal and reactivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Persistent re-experiencing may take the form of nightmares, intrusive thoughts, flashbacks or emotional distress or physical reactivity after exposure to traumatic reminders. Avoidance could take the form of avoiding thinking about the event or avoiding traumatic reminders. Negative thoughts and feelings may include a decreased interest in activities, feeling isolated, exaggerated blame of self or others, or an inability to recall specific features of the trauma. Symptoms of arousal and reactivity may include irritability, aggression, reengagement in risk taking or destructive behaviours, hypervigilance, a heightened startle reaction, as well as numbness and difficulties concentrating and sleeping.

A recent contributor to discussions of and research on trauma and violence is a body of work coming from neuroscience. The neuroscience lens uses research from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies which examine how the brain-body system responds to threat and fear. People who have experienced trauma often continue their lives as if the trauma is still occurring; with every new experience being ‘contaminated by the past’ (van der Kolk, 2014: 53). Posttraumatic stress is not, however, a simple psychological reoccurrence of trauma symptoms but a ‘physical reliving of the trauma, with all the attendant hormonal activation’ (Fishbane, 2007: 400). It is unsurprising therefore, as Leitch, Vanslyke and Allen (2009) note, that the literature is replete with evidence that individuals who have experienced trauma may also suffer from a myriad of short and long term somatic symptoms including loss of bowel and bladder control, shaking, increased heart rate, diabetes and heart disease. Trauma takes a serious psychological and physical toll, many of the symptoms lying beyond the categories of symptoms required for a PTSD diagnosis. This makes healing the wounds of trauma all the more imperative.

A small number of studies have examined the prevalence of traumatic stress among the Rwandan population post-genocide. Utilising a probability sampling strategy of 465 genocide survivors living across Rwanda in 2011, Fodor, Pozen, Ntaganira, Sezibera and Neugebauer (2015) found a mean PCL-C score of 31.4 points (SD = 15.8, max. 79). Using the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, Rugema, Mogren, Ntaganira and Gunilla Krantz (2015), examining a random population sample of 913 Rwandans, found that 124 (13.6 per cent) had a posttraumatic stress disorder. To our knowledge, only one study has previously examined levels of PTSD symptoms among Rwandan genocide perpetrators. This was a study conducted by Schaal and colleagues in 2009. The researchers examined psychiatric morbidity among convicted and unconvicted incarcerated genocide perpetrators (n = 269) and genocide survivors (n = 114). Of the perpetrator sample they found that 13.5 per cent (n = 36) met diagnostic criteria for PTSD, compared to 46.4 per cent (n = 52) of survivors. In addition, 41.4 per cent (n = 111) of perpetrators displayed symptoms of depression and 35.8 per cent (n = 96) had symptoms of anxiety, compared to 46.4 per cent (n = 51) and 58.9 per cent (n = 66) of survivors, respectively. Interestingly, in relation to reconciliation, Schaal et al. (2012) found that among genocide perpetrators, high levels of PTSD were associated with a high desire for reconciliation, whereas for genocide survivors high levels of PTSD were associated with a lower desire for reconciliation. The authors suggest that perpetrators suffering from PTSD are constantly reliving their actions and therefore more inclined to repent, which may lead to greater attitudes towards reconciliation. For survivors with symptoms of PTSD, reliving experiences may perpetuate feelings of hatred and revenge, which may supersede attitudes supportive of reconciliation.

Reconciliation is a relational process that involves a situational repositioning for former adversaries. It requires ‘a radical break or rupture from existing relations’ (Bornemann, 2002: 282). In the post-Rwandan genocide world, both perpetrators and survivors bring psychological wounds, perceived historical wrongs, and posttraumatic suffering to the reconciliatory process. There is clearly a need for more empirical research that examines physical, emotional and psychological influences on genocide perpetrators’ readiness to reconcile, as well as interventions to target the cascade of symptoms that characterise survivors, perpetrators and witnesses (including service providers).

It is also possible that reconciliation potential is associated with the strengths and protective factors that characterise an individual. Most research is problem or symptom focused and does not include data on the positives that may also characterise an individual. Individuals who have experienced trauma and/or perpetrated violence and who are symptomatic in a number of ways also have strengths. These strengths can be engaged during the healing process and can help build a sense of hope and manageability in recipients of services as well as treatment providers (Leitch, 2017). -

3. Methodology

3.1 Population and sample

Since the aim of this study is to examine the reconciliation potential of perpetrators convicted of genocide, the study identified men and women convicted of the crime of genocide in Rwanda. Accordingly, participants in this study are convicted and incarcerated genocide perpetrators that will be released back to their respective communities within the next decade. Specific data concerning specific genocidal acts was not garnered during data collection, because of Institutional Review Board restrictions. Drawing on Ingelaere’s (2008) work, and examining length and year of sentence of the sample, we can determine that the majority of participants were Category 2 (1st & 2nd) perpetrators if sentenced prior to June 2007, and Category 2 (4th and 5th) perpetrators if sentenced after June 2007. Thus, all perpetrators in the sample were considered to be ‘ordinary killers’ who participated in serious attacks, or those who intended to kill in their attacks. Just prior to the current study, Miller (2016) estimates that approximately 30,000 genocide perpetrators remained incarcerated in Rwandan prisons. In an attempt to maintain geographic diversity and representativeness of the different geographical parts of Rwanda, three (3) prisons were selected: Gasabo prison (Kigali City), Muhanga prison (Southern province) and Ngoma prison (Eastern province). According to Rwanda Correctional Services (RCS), these prisons also house high numbers of sentenced genocide perpetrators. Gasabo prison (closed in June 2017) was a male only prison, Muhanga prison is a mixed prison, and Ngoma houses females only. The researchers asked prison officials to identify incarcerated men and women who were sentenced for the crime of genocide. Such a request resulted in a detailed sampling frame of genocide perpetrators in each prison. From these a sample was drawn by RCS, identifying potential participants for the study. As the identification of the sample occurred in administrative offices within each prison, the researchers unfortunately have no information pertaining to those who refused to participate in the study. It is likely that correctional staff excluded those considered too infirm or too mentally disturbed to participate in the study. Those working outside of the prison on the data collection days, would also have not been selected. Potentially perpetrators considered too hostile may have been purposively de-selected from the study.

Specifically, relevant subjects were identified and were asked by the educational officer of the Rwandan Correctional Service if they were willing to participate in the study. Those who agreed were given a verbal explanation of the study aims and procedure and were also asked to sign an informed consent form that was translated into Kinyarwanda (the official language of Rwanda). The informed consent process lasted approximately 20 minutes in Muhanga and Ngoma prison, and almost an hour in Gasabo prison. The Rwandan data collection team felt that this was because Gasabo prison housed perpetrators who had previously lived in the (more urbanised) Kigali area. The ‘more urbanised’ prison population was considered ‘more intellectual’, as well as ‘more suspicious’ than those incarcerated in Muhanga and Ngoma prisons. Overall, and to maintain balance between the facilities, 302 individuals were sampled, with 102 perpetrators sampled from Gasabo prison, 99 perpetrators sampled from Muhanga prison, and 101 perpetrators sampled from Ngoma prison. Women were over-sampled because so little information exists on female perpetrators of genocide.

The study was conducted in Gasabo, Muhanga and Ngoma districts in Rwanda, in 2016. Before the commencement of data collection, a detailed study protocol was submitted and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the corresponding authors. The researchers also received written permission from the then Commissioner General of RCS, Major General Paul Rwarakabije. A small team of Rwandan data collectors received orientation to the project, were trained in the data collection protocols, and helped gather the data from incarcerated genocide perpetrators. These data collectors were members of Rwanda Centre for Council Foundation, an organisation committed to restorative justice practices including council process, known as ‘peace circles’ in Rwanda. Peace circles in Rwanda are a structured group intervention to help people share authentic stories and give voice to their associated feelings and thoughts in a group format in which listening across differences is emphasised. Such peace circles provide a structured process for ‘organizing effective communication, relationship building, decision-making, and conflict resolution’ (Zellerer, 2013: 284). The data collectors from Rwanda Centre for Council Foundation were joined by staff from ARCT-Ruhuka (Association of Rwanda Trauma Counsellors), who both served as data collectors and were on-hand to immediately respond in the event of distress among participants during the data gathering process.3.2 Data collection

Three hundred and two perpetrators completed survey packs. The packs consisted of four separate surveys. These were a basic demographic information form, the Kellner’s Symptom Questionnaire (Kellner, 1987), the PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version (Weathers, Huska & Keane, 1991), and an adapted Readiness to Reconcile or Orientation to the Other measure (Staub et al., 2005). Perpetrators who were able to read and write completed the survey packs themselves during the group process. Those who experienced literacy difficulties were assisted by a data collector who spoke Kinyarwandan. Generally, it took 30-40 minutes for each participant to complete the survey pack.

Specifically, data was collected on several measures of reconciliation, wellbeing, depression, anxiety, somatic symptoms, anger and hostility, trauma, as well as on standard demographics. We describe each of the measures in detail below.

Demographic Information Form.The demographic information form contained questions relating to gender, age, the district the perpetrators lived in before their incarceration, and the district the perpetrators planned to return to after release from prison. In addition, we used the demographic form to ask questions concerning employment prior to the current period of incarceration, plans for employment after release from prison, any contact with family members or friends during the prison sentence, and who, if anyone, would be providing support upon release from prison. We also asked about the year the perpetrators came to prison, the year of expected release from prison, whether the incarcerated perpetrator was sentenced or unsentenced, and whether sentenced by the conventional court or Gacaca system.

Kellner’s Symptom Questionnaire.Kellner’s Symptom Questionnaire (Kellner, 1987) is a 92-item survey examining both, the presence or absence of symptoms and protective factors (well-being) experienced by participants in the previous two weeks. Items are answered in either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ format. The self-report questionnaire may provide greater face and content validity than clinical impressions alone (Polcari, Rabi, Bolger & Teicher, 2014). The questionnaire measures the following symptom subscales: depression, anxiety, anger-hostility and somatic symptoms. Each subscale comprises of 17 symptoms. In addition, the questionnaire examines aspects of wellbeing, specifically contentment, relaxation, friendliness and somatic well-being. For each of the symptom subscales there are well-being indictors. As mentioned earlier, very seldom do researchers gather indicators of well-being, focusing exclusively on symptoms. This deprives both researchers and service providers with important information used to build resilience. In scoring the Kellner Symptom Questionnaire, one point is scored each time a participant responds yes/true to one of the items on the subscale. Depression includes feeling unworthy, desperate/terrible, weary and sad/blue. Anxiety includes feeling tense, shaky, restless and wound up/uptight. Anger-hostility includes shaking with anger, feeling like attacking people, infuriated and irritable. The somatic symptoms subscale includes feeling of not enough air, heavy arms or legs, poor appetite and a choking feeling. Each wellbeing sub scale includes six symptoms. One point is scored each time a participant responds no/false to one of the items on the well-being subscale. Contentment includes feeling well, enjoying oneself and looking forward to the future; relaxation includes feeling peaceful, feeling calm and self-confident. Friendliness includes feeling charitable/forgiving, patient and feeling kind toward people. Physical well-being includes no pain anywhere, feeling fit, and arms and legs feel strong. In-depth analysis of the well-being indicators and their relationship to demographics and symptoms will be the focus of a subsequent article.

The entire questionnaire was translated into Kinyarwanda by the data collection team and was validated for its accuracy separately by a minimum of three speakers fluent in both English and Kinyarwanda. The survey was then pilot tested with a small sample of incarcerated genocide perpetrators in Gasabo prison in 2015. Adjustments were then made to the final version of the translated Kellner’s symptom questionnaire.

Previous research has shown that the Kellner’s Symptom Questionnaire has relatively high reliability across the depression, anxiety, anger-hostility and somatisation subscales (Teicher, Ohashi, Lowen, Polcari & Fitzmaurice, 2015). The original depression subscale is characterised by a Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.94, anxiety = 0.92, anger-hostility = 0.91, and somatic symptoms = 0.86 (Kellner, 1987; Rafanelli et al., 2000; Thompson et al., 2004).

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C).The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder checklist (Weathers, 2008; Weathers et al., 1991) is a widely used self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The items measured correspond with PTSD diagnostic criteria outlined in DSM-IV. The military and civilian versions differ only in how the original trauma is referred to in a number of items (Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte & Domino, 2015). The PCL-C measurement is a self-report rating scale – that varies from (1) ‘not at all’ to (5) ‘extremely’. Participants assess the degree to which they have been bothered by particular problems in the previous month. Statements include repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts or images of a stressful experience from the past; repeated, disturbing dreams of a stressful experience from the past; and being ‘super-alert’, or watchful or on guard. We adapted the PCL-C for our own study purposes by swapping out the words ‘a stressful experience from the past’ with ‘the genocide’, where applicable. The adapted PCL-C was translated into Kinyarwanda by the Rwandan data collection team, and was validated for its accuracy by fluent speakers in both English and Kinyarwanda. Previous studies found that the overall reliability of the PCL-C is very high (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.96) (Conybeare, Behar, Solomon, Newman & Borkovec, 2012; Skeffington, Rees, Mazzucchelli & Kane 2016).

Adapted Readiness to Reconcile or Orientation to the Other Scale.The readiness to reconcile measure, used as our dependent variable, examines how willing and accepting individuals are towards formally hostile groups, and how likely they are to engage in forgiving gestures and behaviours. Specifically, the readiness to reconcile or orientation to the other scale developed by Staub et al. (2005) was adopted. Ervin Staub kindly shared a copy of the scale, which was previously translated into Kinyarwanda. The Readiness to Reconcile Scale contains 45 items, including ‘I ask to be forgiven for my group’s actions against the other group’, ‘I always think about revenge’, ‘I try to see God in everyone’ and ‘I would feel no sympathy if I saw a member of the other group suffer’. In order to reflect the Rwandan reality, political climate, and the fact that the current study examines genocide perpetrators rather than the victims, the reconciliation scale was modified in consultation with the Rwandan data collection team. The team removed items that appeared to predominately focus on the victim’s perspective. For example, items removed from the survey included: ‘To forgive the perpetrators, I need society to punish those who harmed my group’ and ‘The acts of the perpetrators do not make all Hutu bad people’. The adapted reconciliation measure comprises 26 scale items, ranging from 1 to 4 (1 – ‘not at all’ and 4 – ‘a lot’). Items include ‘I would like my children to be friends with members of the other group’ and ‘By working together, the two groups can help our children heal and have a better life’. An examination of the adapted measure used in the current study revealed a relatively high reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.89). Of note is that the reliability achieved in the adapted reconciliation scale is actually better than the original one examined by the Staub et al. (2005), who calculated a reliability that ranged from 0.68 to 0.87 in three different measurements on Rwandan samples. -

4. Results

4.1 Descriptive data

The 302 incarcerated perpetrators sampled for this study were selected from the three correctional facilities mentioned earlier – Muhanga prison (a mixed facility), Gasabo (a male only facility) and Ngoma (a female only facility). As mentioned earlier, the researchers purposefully over-sampled female perpetrators of genocide for two reasons: (1) to gain data on a group largely ignored in the genocide literature, and (2) to ensure sufficient power for within and between group analyses. Overall, from all three facilities 180 perpetrators were male (59.6 per cent) and 122 were female (40.4 per cent). Twenty-one perpetrators from the Muhanga prison sample were females. The age of the perpetrators ranged from 30 years old to older than 70. Specifically, more than half of our sample (54.6 per cent) were between the ages of 45-59 years old, and just over one-third (33.7 per cent) of the sample were older than 60. Only 11.6 per cent of the sample were younger than 44 (age ranged between 30 and 44 years). Consequently, the age data suggest that majority of perpetrators sampled for this study were between 23 and 40 years of age at the time of 1994 Rwanda genocide.

All of the genocide perpetrators in the sample were sentenced. With reference to the sanctioning court, 173 were sentenced through the Gacaca process (57.3 per cent) and 125 through the conventional court system (41.4 per cent). Two genocide perpetrators had been sentenced in both the Gacaca and conventional court. Sentence lengths were calculated by asking what year the genocide perpetrator came to prison, and what year he or she will be released. In spite of a correctional services policy to inform incarcerated people of the date of their release, seventy-three genocide perpetrators (24.2 per cent) said they did not know what year they were to be released. Males were significantly more likely not to know their release date than females. Forty-two males (25.0 per cent) said they did not know their release date, and 31 females (23.0 per cent) did not know their release date. Of those who did know when they would be released, the sentence length ranged from 3 to 30 years. The overall mean sentence length of the sample was M = 16.47 (SD = 4.56, range = 3-30).

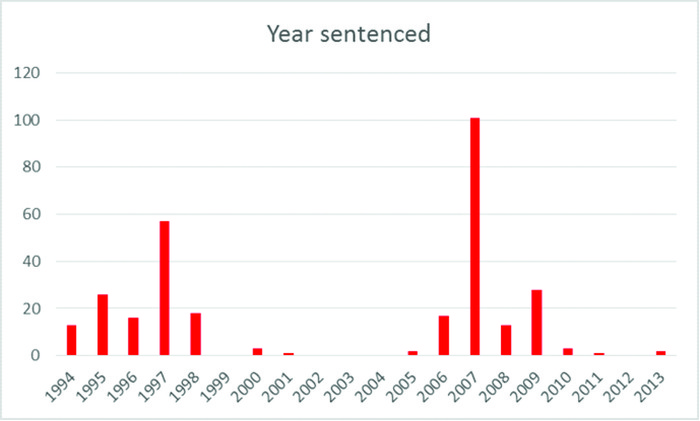

Although it was assumed that difference in length of sentence would exist between those sentenced by the Gacaca and conventional courts, our findings fail to support such hypothesis. There was no significant difference in sentence length between those sentenced through Gacaca and those sentenced through the conventional court system. A difference can be identified, however, between sentencing waves. Our sample can be divided into two distinct sentencing waves: Wave I- 1994-2004, and Wave II- 2005-2013 (see Figure 1). Examining the difference in sentence length between these two waves reveals that the first wave is characterised by a longer mean sentence of 20.2 years, compared to sentences handed in the second wave and averaged 13.4 years. This result was found to be statistically significant (t = 17.59, p < 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences in length of sentence between males and females. Interestingly, females incarcerated in Ngoma prison (prison for females only) had longer sentences than those incarcerated in Muhanga prison, and this difference was statistically significant. Specifically, females sentenced to Ngoma prison were serving sentences of 16.59 years, compared to females in Muhanga who had an average sentence of 14.9 years (t = 17.21, p < 0.001).Figure 1: Sentencing waves of the sample

The majority of perpetrators in the sample (87.4 per cent) reported that they were farmers prior to their incarceration. Of the remaining non-farming perpetrators, professions included baker, builder, bus attendant, businessperson, carpenter, chef, electrician, district advisor, nurse, tailor, teacher and veterinarian. Of the perpetrators, 83.1 per cent indicated that they hoped to return back to farming once they were released.

4.2 Support during incarceration

Contact with family and friends during incarceration was used as a proxy to examine social support available to sentenced perpetrators. Over two-third of our sample of perpetrators (64.6 per cent) reported having regular contact with family or friends during their sentence. However, an interesting profile of visitation emerged when perpetrators were specifically asked about their frequency of visits as a proxy to their actual contact with family and support. Specifically, when asked about the frequency of visits, less than 10 per cent of perpetrators in our sample felt that they had been visited a lot, and a little over a third (35.5 per cent) felt that they had been visited quite a bit. Less than a third of the total sample of perpetrators (30.8 per cent) reported that they had been hardly visited, and about a quarter (24.2 per cent) said that they had never been visited during their sentence. Considering the last two categories of ‘hardly visited’ and ‘never been visited’ provides a striking indication that more than half of the participants in the sample (55.0 per cent) lack essential external social support. This is an extremely important finding that may have far-reaching ramifications on individuals’ ability to overcome their experiences of trauma and recover from some of the somatic and psychological symptoms. Accordingly, such finding may have important implications on reconciliation potential, as well as on the rehabilitation and potential reintegration prospects of study participants.

4.3 Depression

Using the depression subscale of the Kellner Symptom Questionnaire, scores for the depression subscale in the current study ranged from 0 to 23. The mean total scale depression score was 7.55, suggesting that as a whole the sample had raised levels of depression. Just under two-fifths of the sample (39.6 per cent) reported eight or more depressive symptoms, and 10.2 per cent of our perpetrators sample reported scores that are higher than 12 on the Kellner (1987) total scale for depression. Depression scores ≥ 12 are considered clinically significant (Teicher, Samson, Sheu, Polcari & McGreenery, 2010). Males had higher levels of depression compared to females, and such difference was found to be statistically significant (t = 3.80, p < 0.001). Those incarcerated in Muhanga prison had higher levels of depression than in Ngoma and Gasabo prison (F = 7.50, p < 0.001). Given that males reported higher levels of depression than females, it is unsurprising that Ngoma prison, a women’s facility, had lower levels of depression. Interestingly, however, Muhanga prison, a mixed-gender prison had higher depression levels than Gasabo. Certainly, facility level variables such as overcrowding rates, inter- and intra- prison supports, and prisoner-staff relations may be impacting variability in depression scores between Muhanga and Gasabo. Alternatively, the male perpetrators may have been more guarded in their responses than male and female perpetrators in Muhanga prison, thereby downplaying depression scores.

4.4 Anxiety

Looking at anxiety, our overall sample of perpetrators is characterised by low levels of anxiety, with an average score of 5.70 out of a possible 23 on the anxiety subscale of the Kellner Symptom Questionnaire. According to Shibeshi, Young-Xu and Blatt (2007), any anxiety score ≥ 8 is considered to be abnormally high (also see Kellner, 1987). Teicher et al. (2010) suggest that anxiety scores ≥ 12 are clinically significant. About one-third of our sample (32.2 per cent) had an anxiety score that was 8 or higher. A careful examination reveals that males had an overall higher anxiety levels compared to females, and this difference was statistically significant (t = 3.623 p < 0.001). Perpetrators in Muhanga prison reported higher levels of anxiety followed by Gasabo, with Ngoma female prisoners being the least anxious. Such differences were found to be statistically significant (F = 10.45, p < 0.001). The same between-prison pattern exists as we found for depression levels. As before, facility level variables and trust levels of participants may be influencing this relationship.

4.5 Anger-hostility

According to Herman (1997), reduced anger and hostility are essential stages for healing and reconciliation after trauma. The perpetrators in our sample were characterised by extremely low levels of anger and hostility, as measured by the Kellner (1987) hostility subscale. In particular, the mean score observed is 1.57 out of a possible 17. However, and as expected, males were significantly more hostile than females (1.80 vs. 1.20 respectively, with t = 2.26, p = 0.025). Accordingly, statistically significant differences (F = 3.14, p = 0.045) were observed between the prisons due to gender variation in the Ngoma prison for females that was characterised by the lowest levels of anger and hostility (1.1) compared with Gasabo prison for males only (1.8).

4.6 Somatic symptoms

Trauma can take a physical, as well as a psychological, toll on individuals. ‘The body keeps the score’ as van der Kolk (2015) reminds us. Trauma-related somatic symptoms have been associated with a wide range of physical illnesses including cardiovascular problems, eating and sleep disturbances, diabetes, asthma and autoimmune disorders. Overall, our genocide perpetrator sample had raised levels of somatic symptoms, with an average score of 9.60 out of 23. This suggests that perpetrators sampled in our study are experiencing some health issues that may potentially impede their emotional healing and reconciliation as well as their ability to work post-release. Just under two-thirds of the sample (62.8 per cent; n = 189) reported that their body had felt numb or tingling in the previous two weeks, and 53.2 per cent (n = 159) had felt nauseated. 42.9 per cent (n = 129) of the perpetrators had experienced cramps, and 36.0 per cent (n = 108) had upset bowels. 38.4 per cent (n = 116) were having difficulty breathing, and 37.2 per cent (n = 112) reported weak limbs (commonly considered a trauma symptom). Although our findings fail to indicate any statistically significant difference between the mean score of somatic symptoms for men compared to women, the data provide an important insight into the overall compromised health condition of our sample. Such information is essential when considering the holistic reintegration of perpetrators back into local communities upon release. Finally, Ngoma, the women’s prison had the highest scores for somatic symptoms, followed by Gasabo and Muhanga prisons respectively, although the relationship is not statistically significant.

4.7 PTSD symptoms

Related to the above somatic symptoms, participants of the current study were assessed for PTSD symptoms. Overall, the sample of genocide perpetrators examined in this study had elevated PTSD scores, ranging from 16 to 79 out of a possible 85 (M = 40.51, SD = 12.86). Differential cut-off points are typically used by scholars to distinguish between civilians and military personnel completing the PCL-C. Identifying the overall prevalence of PTSD within the population under examination is important in order to reduce false negatives when determining appropriate scale cut-off points (McDonald & Calhoun, 2010). The U.S. National Centre for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (2012) estimates that PTSD prevalence in the general population is <15 per cent, prevalence in Veterans Administration primary care and specialised medical clinics is 16-39 per cent and in VA or civilian mental health clinics the prevalence rate of PTSD is >40 per cent. Suggested cut-off scores are 30-35 for general populations, 36-44 for specialised medical clinics and 45-50 for mental health clinics. They advise that researchers should use lower end scores if using the PCL to screen for PTSD, and higher end scores if using the PCL to aid in diagnosis.

In relation to our sample, more than 66.6 per cent of genocide perpetrators scored above 35. Some 22.8 per cent of the sample had a score higher than 50. There was no difference between perpetrator’s PTSD level and the prison in which they were incarcerated. Males had higher PTSD levels than females. Although the difference does not reach statistical significance to the p = 0.05 level, we believe that this is an important finding because of the overall effect size found by the t-test (t = 3.54, p = 0.080). Experience of PTSD symptoms was highly and significantly correlated with anxiety, depression, somatisation and anger/hostility. Arranging the PTSD symptoms of our sample into categories of intrusion, avoidance and arousal highlights the high levels of PTSD-related symptoms among genocide perpetrators. In our sample, 58.2 per cent reported intrusive memories of the genocide, 41.3 per cent reported intrusive dreams, and 61.6 per cent reported being upset by intrusive reminders. In relation to avoidance symptoms, 62.2 per cent of perpetrators reported that they avoid talking about or having feelings about the genocide, 71.4 per cent had trouble remembering details about it, and 71.8 per cent avoided situations that may remind them of it. Arousal symptoms reported by this sample included trouble falling asleep (38.7 per cent), being easily startled (35.1 per cent), and difficulty concentrating (44.4 per cent). Examining levels of PTSD is important to our understanding of the readiness of individuals to participate in reconciliation endeavours. Specifically, we expect that those perpetrators characterised with higher levels of PTSD will have better potential for reconciliation as they are ‘haunted’ and taunted by their experiences and memories, which they want to put to rest. We discuss this connection in the next section of this article.

Regarding the physical and emotional wellbeing subscales, higher levels of relaxation, contentment, and friendliness were correlated with lower PTSD levels, and these associations were statistically significant. Interestingly, better physical wellbeing was correlated with higher levels of PTSD. As expected, age was negatively and significantly associated with physical wellbeing. The relationship between age and levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms was examined. Although older perpetrators in the sample had lower levels of PTSD, the relationship was not statistically significant.4.8 Adapted readiness to reconcile or orientation to the other scale

Overall participants in the current study had extremely high reconciliation scores (see Table 1). Specifically, a mean score of 64.67 out of a possible 68, characterised the current sample. Females had higher reconciliation scores compared to males (t = –2.70, p = 0.007). Perpetrators in Muhanga prison were characterised by having significantly higher reconciliation scores, followed by Ngoma prison and Gasabo prison. Muhanga prison had eight times higher reconciliation scores compared with Gasabo prison. Reconciliation scores were examined for correlation with the PTSD, Anxiety, Depression, Somatic and Hostility sub-scale scores, as well as with length of sentence. From this examination only, PTSD was found to be positively and statistically correlated with reconciliation, suggesting that higher levels of reconciliation are associated with higher PTSD scores (r = 0.35, p < 0.001). Further, our analysis suggests that lower reconciliation scores tend to associate with longer sentences (r = –0.14, p = 0.048). All of the other Kellner Symptom measures (e.g. Anxiety, Depression, Somatic and Hostility), were not found to have a statistical significance relationship with level of reconciliation. Of most interest, perhaps, is that those who had either no regular contact with family or friends, or a lot of contact with family or friends were more reconciled than those reporting that they had a little or quite a bit of contact (F = 3.16, p = 0.025). There is an apparent anomaly in responses to the statement ‘I would feel no sympathy if I saw a member of the other group suffer’, with 48.2 per cent of participants responding with ‘not at all’, 21.3 per cent ‘a little bit’, 7.6 per cent ‘quite a bit’, and 22.9 per cent ‘a lot’. Such a spread of responses is incongruous to the trends in other responses. It is likely that this discrepancy arose from translation issues related to the double negative.

Table 1 Percentage of perpetrators’ attitudes supportive of reconciliationItem (N = 302) A D I have a relationship with God 99.7 0.3 God will punish those who did terrible things during the genocide 94.2 5.8 I try to see God in everyone 99.0 1.0 I blame my leaders for what happened 85.7 14.3 Members of the other group are human beings 100.0 0.0 Not all Hutu participated in the genocide 83.4 16.6 There were complex reasons for the genocide in Rwanda 93.3 6.7 I feel bad about my actions against other people 85.3 14.7 How a Rwandan killed a fellow Rwandan is inconceivable 94.0 6.0 I cannot accept that some people who might have helped did nothing during the genocide 95.3 4.7 I asked to be forgiven for my actions against the victims 92.4 7.6 I asked to be forgiven for my actions against the other group 85.2 14.8 I accept my punishment 87.0 13.0 I always think about revenge 29.9 70.1 I asked to be forgiven for not acting in a helpful way 92.0 8.0 I should ask for forgiveness and make reparations to the other people 78.7 21.3 I would feel no sympathy if I saw a member of the other group suffer 51.8 48.2 I would like my children to be friends with members of the other group 98.7 1.3 I would work with members of the other group on projects that benefit us all 82.1 17.9 It was hard and dangerous for people to help victims during the genocide 94.7 5.3 By working together as Rwandans we can help our children heal and have a better life 99.7 0.3 The actions of some of the people in my group created a bad reputation for our whole group 98.7 1.3 Some Hutu endangered themselves by helping Tutsi 99.3 0.7 The acts of perpetrators do not make all Hutu bad people 84.7 15.3 Genocide has created great loss for everyone 95.7 4.3 There can be a better future with the Hutu and Tutsi living together in harmony 99.7 0.3 Note. Response categories were dichotomised for clearer representation of the data (A little bit, quite a bit, a lot = agree (A); Not at all = disagree (D)

4.9 Regression models

In order to examine all previously discussed sub-scales and demographic data, two separate multivariate regression models were calculated. Specifically, General Linear Model (GLM) regressions were calculated for males and for females. These models were calculated to examine the effect of each of the variables mentioned earlier in an attempt to detect the relationship between the main variables of the study and readiness to reconcile (the study’s dependent variable). Both models were found to be statistically significant. The estimates presented are standardised coefficients. For males, the Likelihood Ratio χ2 (with 7 df) = 62.41, p < 0.001, and for the female model, the Likelihood Ratio χ2 (with 7 df) = 34.49, p < 0.001. Examining Table 2, the model confirms that those sentenced to either Muhanga or Ngoma prisons demonstrate statistically significant higher reconciliation scores, compared to those sentenced to Gasabo (the reference category in the analysis). Similarly, the female perpetrators in Ngoma prison were characterised by higher reconciliatory attitudes than men incarcerated in Gasabo prison, which was a male only facility, and the reference category. Such comparison was interesting to examine as Muhanga, the examined prison category in the male’s model, was a mixed prison that housed both female and male perpetrators, and it is likely that the mixed environment created a positive atmosphere that was more conducive to reconciliation. Specifically, such finding provides support for the assumption that females tend to be more receptive and ready for reconciliation compared to male perpetrators, and that their presence may have a calming effect on male prisoners which translates into better positioning for reconciliation. Most interestingly, perpetrators with higher levels of posttraumatic stress were more likely to hold stronger reconciliatory attitudes, and this relationship was significant for both males and females. Indeed, studies on growth from trauma suggest that survivors of trauma tend to report profound changes and shift in direction of preferences in their lives (Solomon et al., 1999; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). In the context of the current study, such a shift in direction of preference manifests itself in the form of a desire to reconcile and make amends.

Table 2 General linear model assessing perpetrators’ desire for reconciliationVariable Males (n = 180) Females (n = 122) B (SE) Wald B (SE) Wald Prison Muhanga 5.170 (1.242) 17.305* Prison Ngoma –3.022 (1.834) –2.715* (Ref. Cat. Gasabo) Anxiety –0.007 (0.232) 0.001 –0.052 (0.319) 0.026a Depression –0.179 (0.286) 0.393 0.357 (0.294) 1.477 Somatisation 0.100 (0.169) 0.355 –0.662 (0.218) 0.357** Hostility –0.344 (0.338) 1.035 –0.860 (0.459) 3.505a Length of sentence –0.055 (0.017) 10.607*** –0.006 (0.201) 0.089 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder 0.260 (0.060) 19.069*** 0.344 (0.083) 16.984*** Likelihood Ratio χ2 62.407 (7)*** 34.486 (7)*** *p < 0.050, **p < 0.010, ***p < 0.001; a < 0.1 (verge of significance)

Although there is a relationship between anxiety, depression and physical health scores and levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms among the sample, no significant relationships were found between these three independent variables and reconciliation scores in the male GLM model. Yet, a significant and negative effect was found for the physical health (somatisation) variable in the female GLM model, suggesting that the less healthy female perpetrators are the more likely they are to desire reconciliation. This finding makes sense in that people who are not feeling well tend to seek help and tend to be more forgiving while doing so. Hostility scores in relation to reconciliatory attitudes were bordering significance in the female GLM model. Specifically, the findings suggest that women who are less hostile tend to show more willingness and readiness for reconciliation. The same borderline significance was observed in the female model for level of anxiety, with women who reported higher level of anxiety being less ready for reconciliation. A potential explanation for this finding may relate to the fact that anxiety interferes with a person’s ability to be tolerant of others’ needs. Because ‘wave of sentencing’ was highly correlated with the ‘length of the sentence’, we decided to include length of sentence in the GLM analysis. This was done to eliminate potential multicollinearity effects and also because the variable ‘length of sentence’ enjoyed a better variation. Using this variable in the models yielded significant results for both males and females, meaning that longer sentences increased the perpetrators’ desire for reconciliation. This finding should not come as a surprise, after all, people who are sentenced for long periods of time are likely to want forgiveness and to be released, which makes them more conducive to the idea of making peace and reconciling with former foes. In fact, Ronel and Elisha (2011) argue that many trauma survivors and perpetrators of the genocide can certainly be included in this category as established earlier in this study. Genocide perpetrators can and do continue to develop positive attitudes towards unity and reconciliation, even while suffering negative effects, such as lengthy sentences of incarceration. -

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to collect data on the mental and physical health needs of incarcerated Rwandan genocide perpetrators and to investigate the relationships between mental health, physical health, PTSD symptoms and attitudes towards unity and reconciliation post-release. The sample consisted of perpetrators incarcerated in three Rwandan prisons for the crime of genocide. A little more than a two-fifths of perpetrators were sentenced through the Rwandan conventional court system, and a little under three-fifths were sentenced through the Gacaca process. Given that a reduced sentence was offered in return for confession during the Gacaca process (Carter, 2007), it was expected that there would be a statistically significant mean difference in sentence length between those sentenced through Gacaca and those sentenced through the conventional court system. Interestingly, there was no significant difference. Although we did not ask perpetrators about the nature of their genocide conviction, the Rwandan Correctional Service confirmed that all perpetrators in the sample were involved in killing during the genocide. The likely seriousness of the index offenses is perhaps reflected in the mean sentence length of 16.50 years of the entire sample.

Two distinct sentencing waves can be identified in the sample, with just under half of the sample sentenced during the first seven years after the genocide, and just over half sentenced between 2005 and 2013. A statistically significant difference was found between those sentenced in wave I and wave II. Multiple factors are likely influencers of this punitive differential. It is possible that initial punitive responses to genocidal crimes lessened as time passed. It could also be that those convicted in the years immediately after the genocide had committed particularly egregious crimes or had greater levels of involvement in daily atrocities. Alternatively, desensitisation of sentencers and awareness of chronic overcrowding and subsequent deteriorating conditions within correctional facilitates may have influenced discretionary sentencing decisions. It may also be that as time passes, society begins to rebuild and reconcile. Given that Rwanda has been proactive in institutionalising unity, reconciliation and forgiveness through the Gacaca process, national radio programming (muskewaya), solidarity camps for returnees (ingando) and national community service activities (umuganda), we may assume that attitudes supportive of unity may engender less punitive sentencing responses.

Very few previous studies have examined the needs of Rwandan genocide perpetrators. Schaal et al. (2012) examining a sample of 269 perpetrators (177 men and 92 women) in Kigali and Butare prisons found that 36 per cent of the perpetrators in their sample had syndromal anxiety scores. We report similar findings, with 32.2 per cent of our sample having abnormally high anxiety scores. Schaal et al. (2012) found high levels of depression among both the survivor and perpetrator sample (46 per cent and 41 per cent respectively). Similarly, just under 40.0 per cent of our sample had experienced eight or more depressive symptoms in the previous two weeks, and just over 10.0 per cent of the sample had clinically significant depressive symptoms. Such poor levels of mental health among the sample suggest a dire need for services and intervention that may be essential to improve reconciliation efforts, as well as successful integration.

Given the poor mental health of the sample it is unsurprising that high levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms were also identified, with 66.5 per cent scoring above traditional civilian PTSD cut-off levels, and just under a quarter experiencing extreme levels of PTSD symptomology related to the genocide. Compared to Schaal et al.’s (2012) study, where just 13.5 per cent of perpetrators met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, the current sample is experiencing higher levels of PTSD. The incarcerated perpetrators are experiencing frequent, recurring nightmares concerning the genocide, feeling as if the genocide is happening again, avoiding thinking or talking about the genocide, and having strong physical reactions when reminded of the genocide. It may be that the reality and horror associated with killing may take time to fully manifest itself. Our findings also confirm that perpetrating acts of genocidal violence has long-lasting psychological impacts for the perpetrators themselves. That PTSD symptoms remain some 20 years after the genocide are indicative of the pervasive nature of untreated posttraumatic symptoms, and the intimate nature of genocidal acts committed in Rwanda in 1994.

The sample had raised levels of somatic symptoms, perhaps indicative of both the incarcerative environment and an aging population. Just under half of the perpetrators (47.0 per cent) had experienced six or more somatic symptoms in the previous two weeks, and more than a quarter of the sample (26.7 per cent) had experienced nine or more physical symptoms. Our understanding of the physical health needs of incarcerated genocide perpetrators would be advanced by additional data concerning the physical health issues faced by incarcerated people in Rwandan prisons who are not convicted of the crime of genocide. Certainly, overcrowded prison conditions and limited diets impact physical health symptoms. Although we found a correlational association between high levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms and somatic symptoms, the relationship was in the opposite direction to what was expected. Lower somatic symptom scores were significantly associated with higher levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Such a finding could be a result of a limited variance in a sample with high overall physical health needs. Alternatively, it is likely that not all physical health symptoms experienced by perpetrators are associated with PTSD symptoms.

Similar to Schaal et al.’s (2012) observations, our sample of perpetrators overwhelmingly had a strong desire for unity and reconciliation. Although such a finding may be a result of social desirability bias, given the high levels of coercion placed on the general population to kill during the Rwandan genocide, it is perhaps indicative of a perpetrator group ‘forced’ to participate in crimes of genocide. Engaging in killing has a deep psychological impact rendering the perpetrator a victim of his or her own acts of genocidal violence. Perpetrators with higher levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms were more likely to be desirous of reconciliation than those with lower posttraumatic stress scores. Two decades of persistent re-experiences of genocide, purposeful avoidance of thoughts and memories, arousal and reactivity concretises the will to live in peace and unity with former foes.

Of course, attitudes towards reconciliation do not exist in a vacuum, and unity and reconciliation programming within the Rwandan correctional system, the influence of the reconciliation-focused radio soap-opera Musekewaya, and a top-down, national narrative promoting unity, reconciliation and forgiveness are likely influencers on attitudes towards unity and reconciliation. Certainly, our general linear model indicates that the type of prison is a critical predictor of level of reconciliation. Differential prison programming and specific institutional cultures may be influencing the strength of desires for unity and reconciliation. This said, there were statistically significant differences between male and female perpetrators’ attitudes towards reconciliation, with women having higher reconciliation scores than men.

The statistically significant difference between sentence length and attitudes towards reconciliation is interesting. Longer sentences were associated with lower reconciliation scores, and sentence length remained predictive of reconciliation in our general linear model. Such a finding suggests that there is an optimum sentence length to facilitate reconciliatory attitudes among perpetrators. This is unsurprising given the blended messaging of retributive and restorative justice in the Rwandan post-genocide sentencing approach.

In relation to social supports during incarceration, those experiencing few or no visits and those experiencing many visits were more desirous of reconciliation. Those experiencing regular support from family and friends may already feel greater connections to their communities, and therefore more likely to desire peaceful reconciliation. Likewise, those with limited supports may feel so isolated that unity and reconciliation is viewed as a positive way forward. Efforts by the Rwanda Correctional Service to facilitate and increase connections between incarcerated people and their family members are important, and family support post-release is a critical part of successful community re-entry and reintegration (Berg, & Huebner, 2011; Naser & LaVigne, 2006). Of considerable note, and similar to Schaal et al. (2012)’s findings, PTSD symptoms were positively correlated with higher reconciliation scores. Seemingly, as the experience of PTSD symptoms intensify the desire to reconcile increases. Such a finding suggests that the majority of our incarcerated perpetrators in our sample desire a future where all Rwandans live in peace and unity. With proper mental and physical health care and family reunification support this desire may be realistic.

Several limitations of this study are important to note. While the study aimed to achieve representation of those incarcerated in Rwanda for the crime of genocide, by drawing our sample from different prison locations, we acknowledge that sampling error may have occurred. This may be a result of the fact that the generation of a complete sampling frame of all incarcerated genocide perpetrators was not a feasible option. However, the Rwanda Correctional Service did provide us with an up-to-date list of genocide perpetrators incarcerated in each of the prisons that were included in the study. Another limitation is that, owing to IRB constraints, we were unable to ask perpetrators about their specific crime of genocide. Furthermore, the study was completed more than 20 years after the genocide. As a result, it does not capture potential changes to and interaction effects between trauma symptoms and attitudes towards, reconciliation over time.

Finally, the measures used were validated in western contexts. Constructs such as anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress may be culturally mediated and therefore not applicable to the Rwandan population. For example, Rasmussen, Smith and Keller (2007), studying a sample of West and Central African men and women attended a torture trauma clinic in New York City, observe that sleep disturbances, considered a state of hyper arousal in DSM-IV are frequently linked to nightmares, a typical symptom of intrusion. Similarly, somatic constructs can be culturally mediated. Rasmussen et al. (2007) note that somatic symptoms of distress among West and Central Africans may include a sense of crawling on the scalp, intense heat, and perceived jumping of the heart. Notwithstanding cultural adaptability issues, a rigorous collaborative approach was adopted when developing the translated measurement tools. Drawing on locally accepted definitions while also engaging in back translation helped ensure that the measures used had good face validity and were culturally calibrated and adequate.

Future studies should seek to measure the interaction effects of posttraumatic stress symptoms and attitudes towards reconciliation among those convicted of mass atrocities over time. In addition, a focus on the reintegration challenges and barriers faced by genocide perpetrators as they re-enter communities is needed. Such an examination will enable a deeper understanding of how the dual traumas of genocide and incarceration, shape offender identities, and affect reintegration processes; it may further enable us to examine posttraumatic growth, and how both victims and perpetrators changes their lives adopting new clearer self-identities. -

6. Conclusion

Genuine post-conflict reconciliation is highly desirable yet so often elusive. It requires ‘a radical break … from existing relations’ (Bornemann, 2002: 282). After the Rwandan genocide, opposing sides carry deep psychological wounds while the government urges a narrative of forgiveness and unity. As Mamdani (2001) notes, the guilty majority must find a way of living peacefully with the aggrieved and fearful minority. Our study reinforces the understanding that perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide are still experiencing intense posttraumatic suffering. Two decades after the genocide, it is apparent from our sample of incarcerated genocide perpetrators that they are suffering from high levels of posttraumatic stress. The majority of perpetrators desire unity and reconciliation and have an urgent need for physical and mental health interventions, as well as services that facilitate the rebuilding of family relationships well in advance of release. Improving the well-being of both perpetrators of the genocide and victims can only be a positive development as Rwanda continues to build a unified, reconciled and resilient future.

References American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Becker, H. (1963). Outsiders: studies in the sociology of deviance. New York: The Free Press.

Berg, M.T. & Huebner, B.M. (2011). Reentry and the ties that bind: an examination of social ties, employment, and recidivism. Justice Quarterly, 28, 382-410. doi:10.1080/07418825.2010.498383.

Bijleveld, C., Morssinkhof, A. & Smeulers, A. (2009). Counting the countless: rape victimization during the Rwandan genocide. International Criminal Justice Review, 19, 208-224. doi:10.1177%2F1057567709335391.

Blevins, C.A., Weathers, F.W., Davis, M.T., Witte, T.K. & Domino, J.L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28, 489-498. doi:10.1002/jts.22059.

Bornemann, J. (2002). Reconciliation after ethnic cleansing: listening, retribution, affiliation. Public Culture, 14, 281-304. doi:10.1215/08992363-14-2-281.

Braithwaite, J. (2002). Restorative justice and responsive regulation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Carter, L.E. (2007). Justice and reconciliation on trial: Gacaca proceedings in Rwanda. New England Journal of International and Comparative Law, 14, 41-55.

Clark, P. (2010). The Gacaca courts, post-genocide justice and reconciliation in Rwanda: justice without lawyers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cobban, H. (2002). The legacies of collective violence: the Rwandan genocide and the limits of law. Boston Review, 27(2), 4-15.

Conybeare D., Behar, E., Solomon, A., Newman, M.G. & Borkovec, T.D. (2012). The PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version: reliability, validity, and factor structure in a nonclinical sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68, 699-713. doi:10.1002/jclp.21845.

Daly, E. & Sarkin, J. (2007). Reconciliation in divided societies: finding common ground. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Des Forges, A. (1999). Leave none to tell the story: Genocide in Rwanda. New York: Human Rights Watch.

Dzur, A. & Wertheimer, A. (2002). Forgiveness and public deliberation: the practice of restorative justice. Criminal Justice Ethics, 21, 3-20. doi:10.1080/0731129x.2002.9992112.

Fodor, K.E., Pozen, J., Ntaganira, J., Sezibera, V. & Neugebauer, R. (2015). The factor structure of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among Rwandans exposed to the 1994 genocide: a confirmatory factor analytic study using the PCL-C. Journal of anxiety disorders, 32, 8-16. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.03.001.

Fishbane, M.D. (2007). Wired to connect: neuroscience, relationships, and therapy. Family Process, 46(3), 395-412. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00219.x.

Galtung, J. (2001). After violence, reconstruction, reconciliation and resolution: coping with visible and invisible effects of war and violence. In M. Abu-Nimer (ed.), Reconciliation, justice and coexistence (pp. 3-24). New York: Lexington Books.

Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in public: microstudies of the public order. New York: Basic Books.

Herman, J.L. (1997). Trauma and recovery: the aftermath of violence – from domestic abuse to political terror. New York: Harper Perennial.

Ingelaere, B. (2008). The Gacaca courts in Rwanda. In L. Huyse & M. Salter (eds.), Traditional justice and reconciliation after violent conflict: learning from African experiences (pp. 25-60). Stockholm: International IDEA.

Jere, R.J. (8 April 2019). Rwanda unvanquished: 25 years after the genocide. Retrieved from https://newafricanmagazine.com/?p=18577 (last accessed 3 June 2019).

Kalayjian, A. & Paloutzian, R.F. (eds.). (2009). Forgiveness and reconciliation: psychological pathways to conflict transformation and peace building. New York: Springer.

Kellner, R. (1987). A symptom questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 48, 268-274.

Kinzer, S. (2014). Reconciliation and development in Kagame’s Rwanda. Brown Journal of World Affairs, 20, 93-101.

Lambourne, W. (2016). Restorative justice and reconciliation: the missing link in transitional justice. In K. Clamp (ed.), Restorative justice in transitional settings (pp. 55-73). New York: Routledge.

Lazare, P. (2004). On apology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Leitch, L. (2017). Action steps using ACEs and trauma-informed care: a resilience model. Health & Justice, 5, 1-10. doi:10.1186/s40352-017-0050-5.

Leitch, M.L., Vanslyke, J. & Allen, M. (2009). Somatic experiencing treatment with social service workers following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Social Work, 54, 9-18. doi:10.1093/sw/54.1.9.

Mamdani, M. (2001). When victims become killers: colonialism, nativism, and the genocide in Rwanda. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

McDonald, S.D. & Calhoun, P.S. (2010). The diagnostic accuracy of the PTSD checklist: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 976-987. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.012.

McDoom, O. (2013). Who killed in Rwanda’s genocide? Micro-space, social influence, and individual participation in intergroup violence. Journal of Peace Research, 50, 453-467. doi:10.1177/0022343313478958.

Meierhenrich, J. (2008). Varieties of reconciliation. Law & Social Inquiry, 33, 195-231. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.2008.00098.x.

Meierhenrich, J. (2014). What role for reconciliation? In J. Meierhenrich (ed.), Genocide: a reader (pp. 470-473). New York: Oxford University Press.

Miller, K. (2016). Are they forgivable? Aeon. Retrieved from https://aeon.co/essays/can-rwanda-s-genocide-perpetrators-find-a-path-to-forgiveness (last accessed 10 May 2016).