Gendered Divides: Exploring How Politicians’ Gender Intersects with Vertical Affective Polarisation

-

1 Introduction

Recent developments demonstrate that polarisation is gripping established democracies across the globe. Both electoral polarisation (i.e. the electoral rise of anti-system parties) (Casal Bértoa & Rama, 2021), party system or ideological polarisation (i.e. the increased distance in policy positions between parties) (Dalton, 2021) and affective polarisation (i.e. negative animosity between other-minded voters and politicians) (Reiljan, 2020) appear to be on the rise. Polarisation is widely recognised as a significant challenge to contemporary democracies (Somer & McCoy, 2018), with potential far-reaching consequences that extend beyond the political realm and impact society as a whole (McConnell et al., 2018).

This article focuses on affective polarisation. Although this phenomenon was initially described in the US context as negative feelings between Democrats and Republicans (Iyengar et al., 2012), recent studies have shown that affective polarisation also occurs in multi-party contexts in European countries (Harteveld, 2021; Reiljan, 2020; Wagner, 2021). The core of this concept is that citizens feel sympathy towards partisan in-groups and antagonism towards partisan out-groups (Wagner, 2021). Although most studies concentrate on how citizens feel about other-minded citizens (i.e. horizontal affective polarisation) (Reiljan, 2020; van Erkel & Turkenburg, 2022; Wagner, 2021), these negative feelings could also be developed against parties in general and against politicians of particular parties (i.e. vertical affective polarisation). In this article, we focus on the prevalence of vertical affective polarisation in a least-likely case (i.e. the multi-party and consociational context of Belgium; Bernaerts et al., 2022). Furthermore, we bring in two new elements, both related to the role of individuating information in the assessment of politicians (Fiske & Neuberg, 1990). Individuating information includes factors or details unique to a specific individual, such as specific personality traits, socio-demographic characteristics or political/policy positions. We focus on politicians’ gender, which is not only a demographic characteristic but also carries a significant social and psychological weight that can impact individuals’ attitudes and interactions. As such, politicians’ gender potentially moderates the relationship between (ideological) disagreement and affective polarisation in two different respects.

A first element that we test is whether gender dissimilarity exacerbates the perception of ‘out-group’ belonging and the negative feelings associated with it. Building on insights from Social Categorisation Theory (Turner, 1987) and the Common Ingroup Identity Model (Gaertner et al., 1993), we investigate whether voters have more negative feelings towards other-minded politicians of the opposite gender. We hypothesise that gender functions as a superordinate identity that is shared and unites people even if they disagree with each other. Conversely, belonging to a different gender category could exacerbate negative feelings, as socio-demographic dissimilarity adds to dissimilarity based on policy disagreement.

A second and alternative expectation is that gender stereotyping reinforces affective polarisation. The literature on gender stereotyping points to a number of stereotypical patterns in which female politicians are more likely to be perceived as competent in ‘soft’ issues linked to the traditional domain of the family, such as education, healthcare and helping the poor. Men, on the other hand, would do a better job with hard issues, such as the military, foreign trade and taxes (see, for example, Devroe & Wauters, 2018; Dolan, 2014; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993). Building on the literature on motivated gender stereotyping (Kundra & Sinclair, 1999), we investigate whether voters have more negative feelings towards other-minded politicians taking stances on issues for which politicians with a specific gender are generally perceived to be less competent. The reasoning here is that perceived incompetence adds to negative feelings based on policy disagreement.

In sum, we have three research questions:

RQ1: Do voters evaluate the psychological traits1x Druckman and Levendusky (2019) distinguish four ways to measure affective polarisation in surveys (see later). We link here to their second and third approach by asking respondents to assess the psychological traits of politicians, including their level of trustworthiness. As such, we take negative evaluations of politicians’ perceived psychological characteristics as an indicator of affective polarisation. of politicians they do not agree with as more negative in a consensus democracy?

RQ2: Is this effect moderated by (the difference in) the gender of the politician and the voter?

RQ3: Is this effect moderated by the link between the gender of the politician and the nature of the policy issue on which the politician takes a stance?

We find that, even in a multi-party consociational political system as Belgium, voters evaluate psychological traits of politicians they disagree with more negatively compared to politicians whose views they share. This indicates that ideological disagreement is a powerful force in shaping voters’ perceptions. Contrary to our expectations, the relationship between ideological disagreement and vertical affective polarisation is not moderated by politicians’ gender, and the prevalence of vertical affective polarisation is, as such, not reinforced by gender dissimilarity or gender stereotyping. -

2 Affective Polarisation

Affective polarisation, that is, the negative animosity between other-minded voters and/or politicians, or the extent to which partisans hold positive feelings towards their own party (the in-group) and dislike politicians and voters of other parties (the out-group), is considered by several authors to be increasingly prevalent in many contemporary Western societies (Abramowitz & Webster, 2016; Iyengar & Westwood, 2015; Reiljan, 2020; but see Fiorina et al., 2008, for a more critical account). A key characteristic of affective polarisation is the perception of difference rather than actual difference. People who identify with particular groups often believe that out-group members are radically different from themselves and that in-group members are highly similar, despite this not necessarily being the case (Levendusky & Malhotra, 2016). Affective polarisation is driven by different factors. First, while the foundational Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, 1979) does not specifically address partisanship and ideological identity, subsequent political science literature has extended the theory to include them as a form of social identity (Huddy, 2001). This perspective posits that partisanship and ideological identity evoke positive feelings towards the in-group and negative emotions towards the out-group (Bolsen & Thornton, 2021; Iyengar et al., 2012). As such, supporting a party is not just a choice confined to the political sphere; it also has an impact on all walks of life (Mason, 2015). A second factor that causes affective polarisation is the fact that politicians and parties take more extremist ideological positions than before. Put differently, party system or ideological polarisation is thought to stimulate affective polarisation: when actual and perceived ideological distances between parties are large, affective polarisation tends to be higher (Reiljan, 2020; Rogowski & Sutherland, 2016).2xThere is, however, an on-going debate over the extent of such ideological polarisation. We do not aim to take position in this debate, but we rather argue that while there are important connections between affective and ideological polarisation (Abramowitz & Webster, 2016), we consider them as theoretically and empirically distinct concepts. Hence, in this article, we focus exclusively on the affective dimension of polarisation (and not so much on ideological polarisation). A third factor that is suggested is ‘social sorting’, that is, the correspondence of partisan division lines with existing social cleavages (Reiljan, 2020; Robison & Moskowitz, 2019; Wagner, 2021). Ethnic, religious or other cleavages that have existed in societies for many decades and that run parallel with partisan cleavages could strengthen social identity feelings and the corresponding positive and negative feelings.

Previous research, furthermore, highlights that institutional features of political systems can attenuate affective polarisation. More in particular, European countries with consensus institutions (including PR electoral systems and multi-party coalitions) are found to have lower levels of polarisation (Bernaerts et al., 2022). However, even in these countries where electoral volatility is on the rise (Dassonneville, 2018), where simultaneously holding multiple partisan identities is possible (Wagner, 2021) and where partisanship has always been a contested concept because of its lack of stability and predictive power (Bankert et al., 2017), there is considerable evidence to suggest that affective polarisation is becoming increasingly prevalent (Reiljan, 2020; Wagner, 2021; Westwood et al., 2018).

The burgeoning field of research on affective polarisation has primarily focused on horizontal aspects of polarisation. As such, vertical affective polarisation currently remains underexposed, especially in research conducted in consensus democracies (van Erkel & Turkenburg, 2022; Wagner, 2021). Our first aim is, therefore, to investigate the prevalence of vertical affective polarisation in the Belgian context, a textbook example of a consensus democracy (RQ1). More in particular, we will assess whether voters associate negative character traits with politicians they disagree with. In multi-party systems in Europe, partisan identities are less strong than in the US and the out-group party is generally not a single party but all parties except the preferred one (Wagner, 2021). This makes the operationalisation of affective polarisation more difficult in such contexts. As a consequence, some scholars argue to use the broader concept of ‘ideological identity’ rather than ‘partisan identity’ as a source of affective polarisation (Bantel, 2023; Wagner, 2021). That is the logic we also follow in this article. We use the level of ideological disagreement as a proxy to capture ideological identity. In other words, we conceptualise other-minded politicians as politicians with whom one disagrees in ideological terms, rather than politicians from any other party. The level of disagreement indicates how far away this politician is from one’s own ideas. We expect that when voters agree with a candidate or politician, they tend to give that person positive evaluations without any further critical engagement and, vice versa, for candidates they disagree with. These evaluations, and hence also the level of affective polarisation, will be measured as an assessment of the psychological characteristics of politicians (see later).

H1: Voters will evaluate the psychological traits of Belgian politicians presenting policy positions they disagree with as more negative compared to politicians presenting policy positions they agree with. -

3 The Moderating Effect of Politicians’ Gender

The second aim of this article is to investigate whether the relationship between ideological disagreement and vertical affective polarisation (our dependent variable measured by means of evaluations of politicians’ personality traits; see later) is moderated by politicians’ gender, thereby contributing to the growing scholarship on gender and affective polarisation (Klar, 2018; Ondercin & Lizotte, 2021). This can be linked to discussions about the role of individuating information, encompassing unique factors or characteristics specific to individuals, such as particular personality traits, socio-demographic characteristics or political/policy positions (Fiske & Neuberg, 1990). In reality, voters’ evaluations of politicians are likely to reflect both ideological and biographic sources of information (Rogowski & Sutherland, 2016). Indeed, previous research identifies a wide range of personal factors such as characteristic traits (Druckman, 2004; Funk, 1997) and stereotypes based on candidates’ ethnicity (Jacobsmeier, 2014; Van Trappen et al., 2020), gender (Devroe & Wauters, 2018; Dolan, 2014; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993) and religion (Bolce & De Maio, 1999; McDermott, 2009) that influence voters’ evaluations of politicians. Given this context, when voters are presented with individuating information about candidates, the relative significance of policy (dis)agreement may either diminish or intensify, leading to reduced or increased levels of vertical affective polarisation, respectively. Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley (2021) argue, in this regard, that affective polarisation can also stem from other non-partisan identities that divide the world into in-groups and out-groups, such as ethnicity, religion or opinion-based groups. Furthermore, Rogowski and Sutherland (2016) found that adding biographical information to a politician’s profile can mitigate affective polarisation as politicians with divergent opinions were evaluated less negatively when more biographical background information was provided. However, we hypothesise that the nature of the biographical information is crucial: while general or biographical details that signal similarity may improve evaluations, specific negative information or information that emphasises differences may exacerbate negative feelings. We centre our attention on politicians’ gender with the aim of uncovering whether the relationship between (ideological) disagreement and voters’ evaluation of the psychological traits of politicians is moderated by gender dissimilarity (RQ2) and/or gender stereotyping (RQ3). We hypothesise that (ideological) disagreement has more severe consequences in terms of negative feelings towards a politician when specific negative information is available. This could either be information on characteristics of a politician that underscores differences with the evaluator (gender dissimilarity) or information aligning with stereotypes about particular social groups that undermines favourable evaluations of that politician (gender stereotypes).

More specifically, for the former reasoning, we expect that gender dissimilarity reinforces the prevalence of affective polarisation. This can be linked to Social Categorisation Theory highlighting that people tend to view individuals as belonging to distinct social categories based on their salient attributes, such as gender, ethnicity and age (Turner, 1987). These social categories influence our sense of connection with, or alienation from, others because people are likely to take into account whether they belong to the same social category as someone they are evaluating. In-group members are generally assumed to be more similar to the perceiver in terms of attitudes, values and personality. As similarity is known to breed familiarity and more positive evaluations (Sears, 1983), individuals tend to have more favourable evaluations of in-group members than of out-group members (Bauer, 2015).

The Common Ingroup Identity Model (Gaertner et al., 1993), furthermore, states that highly salient superordinate identity categories, such as gender, can potentially reduce intergroup bias when two out-group members belong to the same superordinate in-group (or the other way around when out-group members also belong to the superordinate out-group). Not all identity characteristics are equally strong to temper other differences, however. Brewer (1991) argues that identity groups who simultaneously provide a sense of belonging and a sense of distinctiveness have the greatest potential to function as superordinate identity moderating other differences. Additionally, for a superordinate identity to effectively temper other differences, individuals must (1) consider themselves to be members of a specific group, (2) they need to have a common understanding of what it means to be part of this group and (3) the identity category must be salient. Gender identity, when cohesive and salient, can function in this way. However, Klar (2018) demonstrated that, in the US, gender identity fails to act as a unifying superordinate category because Republicans and Democrats differ in their conceptions of gender, respectively adopting a ‘traditional’ and a more ‘egalitarian’ view on the role of women. As a result, gender identity did not mitigate distrust towards out-group members and, in some cases, exacerbated polarisation.

Gender identity becomes salient primarily in contexts where gender inequality is more pronounced. In such environments, gender identity can evoke strong identification and a sense of solidarity among individuals (e.g. “We must unite as women against this injustice”). This heightened salience can interfere with affective polarisation, as gender identity becomes more central in individuals’ evaluations of others in these cases. Relatedly, the gender affinity effect in voting behaviour highlights how voters are more likely to support candidates of the same gender, demonstrating the significance of gender identity in shaping political preferences (Sanbonmatsu, 2002).

In regions such as Flanders (Belgium), where there is a broad societal consensus on women holding prominent positions in politics and higher levels of gender equality (see later), gender identity may be less salient. As a result, the moderating effect of gender on affective polarisation may be less pronounced. Despite this overall gender-neutral environment in Flanders, we do acknowledge that the cohesiveness of gender identity, as exemplified by the gender affinity effect (Marien et al., 2017), still exists to some extent. This makes it plausible that gender may function as a moderating variable in the relationship between policy preferences and voter aversion, potentially reducing negative feelings towards politicians of the same gender.

Based on these arguments, we propose that when voters disagree with politicians of the same gender, negative feelings will be tempered. Conversely, when voters find themselves in disagreement with politicians of the opposite gender, these politicians will be categorised as belonging to a (perceived) ‘double out-group’, marked by differences not only in policy positions but also in gender. This dual distinction has the potential to amplify intergroup bias, consequently leading to a more negative evaluation of individuals associated with this ‘double out-group’. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H2: Voters will evaluate the psychological traits of politicians of the opposite gender they do not agree with more negatively compared to politicians of the same gender they disagree with.

Yet, there is also another theoretical reasoning possible, which is linked to gender stereotyping and the nature of policy issues. Issue competence stereotypes, that is, the different expectations among voters about the types of issues handled well by male and female politicians, have proved to be the most consistent form of political gender stereotyping (see, for example, Dolan, 2014; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993). Although there is some variation over time and across contexts, female politicians are generally more likely to be perceived as competent in soft-policy issues linked to the traditional domain of the family, such as education, healthcare and helping the poor, whereas men would do a better job with hard-policy issues, such as military spending, foreign trade, agriculture and taxes.

When voters do not agree with the policy positions presented by a politician and when, on top of that, voters perceive some kind of incongruity between politicians’ gender and the nature of the policy issues for which they present their opinions, this might result in the activation of stereotypes (Kunda & Thagard, 1996) and, hence, lead to a more severe negative evaluation of (the characteristic traits associated with) that politician. For female politicians, the violation of the prescriptive aspects of gender stereotypes is higher when they present policy positions dealing with topics close to the public sphere, such as the economy or national defence, compared to positions where they engage with topics close to the private sphere, such as childcare and education (Burrell, 1995). This can also be linked to Motivated Gender Stereotype Theory (Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993; Kundra & Sinclair, 1999) arguing that individuals will only use feminine/masculine stereotypes to negatively judge female/male politicians when they perceive a conflict or disagreement with that particular woman or man.

Based on these arguments, we expect that:

H3a: Voters will evaluate the psychological traits of politicians they do not agree with more negatively when female candidates proclaim policy positions for hard-policy topics compared to male politicians proclaiming similar policy positions

H3b: Voters will evaluate the psychological traits of politicians they do not agree with more negatively when male candidates proclaim policy positions for soft-policy topics compared to female politicians proclaiming similar policy positions -

4 Methodology

This study is conducted in Flanders, the largest region of Belgium. Belgium has a number of characteristics that should in principle temper the prevalence of affective polarisation (especially compared to the US) and is therefore a least-likely case to find affective polarisation. Electoral volatility is rising in recent years making partisanship a fuzzy concept (Dassonneville, 2018), Belgium’s list PR system allows the parliamentary representation of many parties and urges these parties to form coalition governments (Timmermans, 2017), and the country has a long history of consociational decision-making according to which elites try to find compromises between different societal groups (Lijphart, 1969). Previous research indicates that countries with these kinds of consensus institutions (including PR electoral systems and multi-party coalitions) have lower levels of polarisation (Bernaerts et al., 2022). Also for the effect of gender as moderating variable (RQ2 and RQ3), Flanders is a least-likely case, as the number of female MPs is high in international-comparative perspective (IPU, 2021) and women also occupy prominent positions in governments on all policy levels. As Flemish voters have been extensively exposed to the presence of women in top political positions, the presence of stereotyping patterns should in principle be tempered.

In order to test our hypotheses, an online survey experiment was designed in which hypothetical politicians were presented to respondents in written messages in which their gender, some biographical information and their policy position on a number of issues were included. Our study used a 2 × 2 × 3 mixed complete block design. The politician’s gender (male vs. female) and the policy position (outspoken leftist or outspoken rightist) were manipulated as between-group factors. Following Krook and O’Brien (2012), three different policy issues were manipulated as within-groups factor to capture issue competence stereotypes: one topic that is generally perceived as being soft policy (childcare), one hard-policy topic (defence) and one neutral topic (climate).3xThis categorisation is, furthermore, based on an extensive review of 16 international studies on the assignment of policy issues to men and women by three key actors, that is, (mass) media, voters and party elites, and we also checked the appointment of Flemish male and female ministers to these issue domains (Devroe & Wauters, 2018).

We decided not to offer party labels to the respondents in order to fully capture the effect of ideological disagreement. This might, on the one hand, lower the social identity effect as it is not entirely clear to which party the presented politician belongs, leading to lower levels of affective polarisation. On the other hand, Lelkes (2021) demonstrated that (extremist) political positions have a larger effect on affective polarisation than the party label, which would lead to the expectation that polarisation increases when only ideological positions are presented. By offering respectively an outspoken leftist and rightist profile, we also connect to the reasoning of Wagner (2021), who argues that affective polarisation in multi-party settings should be defined and assessed as the extent to which politics is seen as divided into two distinct camps, each of which may consist of one or more parties. In the US context, research on affective polarisation generally assumed the existence of positive in-group identification towards a single party, but this is not appropriate for multi-party contexts. By grouping politicians according to ‘ideological camp’ rather than specific party labels, we aim to reflect this broader conceptualisation and acknowledge that voters may use ideological heuristics to categorise politicians as in-group or out-group members.

Respondents were randomly assigned to three different treatments in the experimental design. After each text message, they were asked to complete a list of questions about the presented politician and his or her policy position, before continuing to the next profile. The order of the issue domains was randomised in order to control for learning or order effects. There was also a random variation of male and female politicians and of outspoken leftist or rightist politicians.

The presented stimuli included several elements: a written message, including the politician’s policy position, and a facial silhouette of the presented politician. The text messages were outspoken rightist or leftist and were based on a mix of the party programmes of the Flemish rightist parties (Open VLD, N-VA and Vlaams Belang) and the Flemish leftist parties (sp.a, Groen and PVDA).4xPilot tests of the experimental design (among student samples) confirmed that the ideological orientation of the various policy positions was sufficiently clear and interpreted as outspoken leftist or rightist. As physical appearance also impacts voters’ perceptions (Lammers et al., 2009) and names can evoke certain prejudices, we decided not to include pictures or names and opted for a visual presentation of the gender cue by means of facial silhouettes. In all other respects, speeches and questionnaires were identical in order to keep hidden the intention of our study. An example of the presented profiles and a translation of the different text messages can be found in the Appendix.

Manipulation checks were included to verify whether respondents were able to correctly answer questions about the politician and the content of the message. All respondents had to answer a question about the sex of the presented politician after the first treatment. Respondents who were not able to correctly answer this question could not further complete the questionnaire, and their answers were not taken into account for the data analysis.5xThe incorrect answers are more or less equally spread over the different issue domains and over the different politician’s profiles (male or female, outspoken leftist or rightist). The percentage of incorrect answers ranges from 0.80% to 6.00% for all 12 presented profiles. Because of the risk of a selection effect, we made a comparison between the final sample and respondents who could not answer the manipulation check correctly. These groups do not differ substantially on important aspects. There is a small selection bias in that our final sample is slightly younger, but there are no outspoken differences concerning gender and level of education. In order to control for the possible intervening effect of respondents’ characteristics, respondents were randomly assigned to one of the different treatments, and comparisons were made between experimental groups. As there were no significant differences on respondents’ background variables (age, gender or level of education) across the treatments, we can be confident that the random assignment worked as intended.

The experiment was conducted in February 2020 among a sample of the general Flemish population. Respondents were drawn from Bilendi’s internet-based access panel, which is the largest online panel in Flanders with about 150,000 potential respondents.6xAlthough it is difficult to determine how well the online panel members represent the general population, we tried to maximise their representativeness. We set several quotas: a hard quota for the gender of the respondents and soft quotas for their age and level of education. In addition, our sample was weighted for gender and age (weighting factors ranging from 0.79 to 1.14). An invitation to participate was sent to 3,891 respondents. 2,723 of them actually received and read7xThe other invitations were apparently sent to invalid or outdated email addresses. the invitation and 966 agreed to participate. After omitting respondents who could not correctly answer the question about the sex of the first presented candidate (see above), we retained 605 participants,8xA power analysis confirms that our analyses are sufficiently powered with this sample (see Appendix). which is a response rate of about 22%. As each respondent had to assess three vignettes, we have a total number of observations of 1,084. In order to avoid post-treatment biases (Montgomery et al., 2018), no additional categories of respondents were excluded from this sample.9xTo test the robustness of our results, separate analyses (available upon request) were performed for those respondents (4) that could find out the purpose of the research and so-called speeder-respondents (51) who completed the survey faster than half the median completion time. However, the results of these analyses are in line with the results for the full sample, which adds to the robustness of our findings. Therefore, no additional respondents were excluded. A description of the basic characteristics of the respondents can be found in the Appendix (see Table A.1).4.1 Dependent Variables

The question arises how affective polarisation can be operationalised in empirical research at the individual level. Druckman and Levendusky (2019) distinguish four ways to measure affective polarisation in surveys: (1) a thermometer rating how warm respondents feel about particular parties, politicians or party voters (Robison & Moskowitz, 2019); (2) assessing how well particular psychological traits are applicable to particular parties, politicians or party voters; (3) indicating how much trust respondents have in particular parties, politicians or party voters (Druckman & Levendusky, 2019); and (4) measuring social distance by assessing how comfortable one feels with people from another party as a friend, neighbour or as someone who marries their child, which is called the social distance or Bogardus Scale (Bogardus, 1933; Iyengar et al., 2012).

We link here to the second and third approach, that is, assessing psychological traits of politicians (including their level of trustworthiness) in order to grasp the level of affective polarisation. Many studies focus on psychological traits as explanatory factors to measure higher or lower levels of affective polarisation (Luttig, 2017; Rice et al., 2021), but only a few studies use the evaluation of politicians’ psychological traits to measure affective polarisation. Most notably, Iyengar et al. (2012), who coined the term ‘affective polarisation’, distinguish between positive traits, such as patriotism, intelligence and honesty, and negative traits such as hypocrisy, selfishness and meanness. The score on negative traits and explicit dislikes listed towards the opposing party is taken as an indicator for affective polarisation in their study. A similar approach is adopted by Garrett et al. (2014) and Hobolt et al. (2021). They argue that voters are more critical towards acts of politicians from the opposing side and attribute more blame to them for unpopular decisions. As a consequence, voters will rate politicians from the opposing side lower on psychological characteristics, resulting in more negative feelings towards them.

After each presented politician, our respondents were asked to evaluate the politician in terms of perceived general competence, and they had to indicate how applicable a range of psychological characteristics were to the presented politician (on a fully labelled 7-point scale ranging from 1 [very inapplicable] to 7 [very applicable]). The following characteristics were included: ambitious, caring, flexible, hard, helpful, sensitive, soft, strong leader and trustworthy.10xIt is important to note that certain traits can have multiple interpretations. ‘Ambitious’, for example, might be seen positively as a sign of drive and determination by some respondents, while others might perceive it negatively as self-serving or overly aggressive. ‘Soft’ might be viewed positively as empathetic and considerate, or negatively as weak and indecisive. Similarly, ‘hard’ can be interpreted positively as strong and resolute, or negatively as harsh and unyielding. While some of these traits may carry a positive connotation, the evaluation scale allows respondents to express both positive and negative perceptions. Lower ratings on the scale (closer to 1) indicate that respondents perceive these traits as inapplicable or lacking in the politician, which captures negative evaluations of politicians’ perceived psychological characteristics as an indicator of affective polarisation.4.2 Independent and Moderator Variables

Respondents’ (dis)agreement with the presented policy positions was measured on a fully labelled 7-point scale ranging from 1 (very much disagreeing) to 7 (very much agreeing). This was recoded into a continuous variable ranging from 1 (very much agreeing) to 7 (very much disagreeing), with the purpose of allowing higher values indicating higher levels of disagreement. The politicians’ policy position is a simple binary variable with the categories Outspoken Leftist (0) and Outspoken Rightist (1).

In order to capture gender (dis)similarity, we include a binary variable indicating whether the presented politician and the respondent have the same gender (0) or different genders (1). In order to analyse the effect of stereotypes, we run analyses on subsamples, based on the issue domain at stake – respectively, childcare (soft-policy issue; linked to female attributes), and defence (hard-policy issue; linked to male attributes).4.3 Control Variables

In the multivariate analyses presented below, we also include a series of socio-demographic and political control variables. Respondents’ level of education was measured by the highest obtained degree: 1 = no degree, 2 = primary education, 3 = lower secondary education, 4 = higher secondary education, 5 = non-university higher education and 6 = university education. This was recoded in a binary variable: ‘Lower Educated’ (including categories 1, 2, 3 and 4) and ‘Higher Educated’ (including categories 5 and 6). A control variable was also included for the ideological position of the respondents. Ideological positioning was measured by self-placement on a 7-point left-right scale ranging from very rightist (1) to very leftist (7). The gender variable for the respondents is a simple binary variable with the categories Male (0) and Female (1). Age (number of years) is a discrete variable. We also include the kind of issue (Defence or Childcare, with Climate as reference category) as a control variable in the aggregated analyses.

-

5 Results

This section is divided into two parts. The first section (5.1) focuses on the extent to which respondents’ ideological disagreement with politicians’ policy positions (independent variable) affects their evaluation of the psychological characteristics of these politicians (dependent variable). In Section 5.2, we present more in-depth explanatory analyses focusing on the potential moderating effect of gender dissimilarity and issue competence stereotyping.11xIn order to ensure the robustness of our findings, we conducted several additional analyses. First, we introduced disagreement as a dummy variable, confirming the results of our analyses when disagreement was treated as a continuous variable (see Tables A.7-A.10 in the Appendix). Second, we performed subsample analyses based on the respondents’ political orientation (left or right; see Tables A.11-A.16 in the Appendix), gender (male or female; see Tables A.17-A.22 in the Appendix) and whether they agreed or not with the presented policy positions (see Tables A.23-A.28 in the Appendix). These analyses reaffirm our findings, showing little to no significant interaction effects.

5.1 Respondents’ Evaluation of Politicians’ Psychological Characteristics

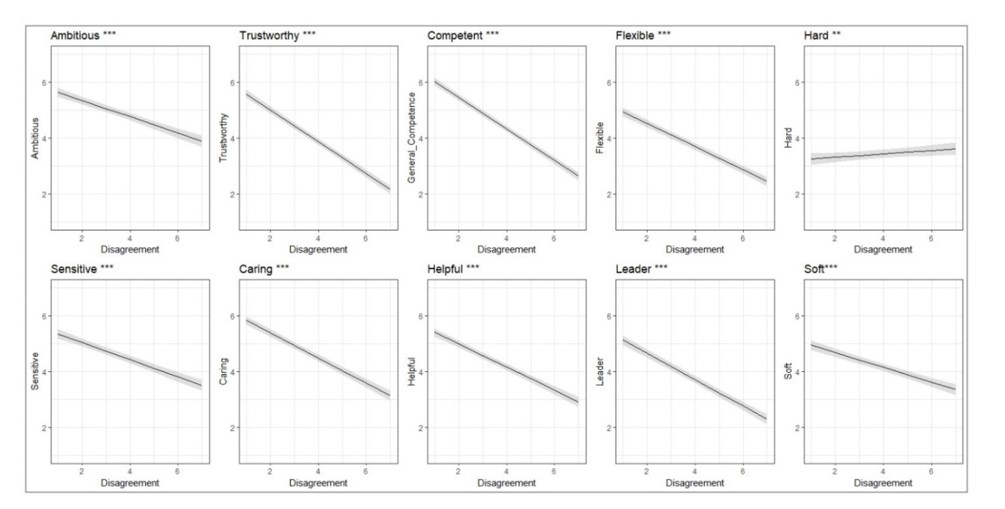

A number of regression analyses with respondents’ evaluation of the politicians’ psychological characteristics and general competence to function in politics as main dependent variables were conducted (RQ1). These analyses were performed at the aggregated level, implying that the total number of observations increases to 1,815 (605 × 3) and that we also control for the nature of the policy issues in the regression models. All models were checked for multicollinearity by looking at the variance inflation factors (VIF), which never exceeded 1.20. The full regression models can be found in the Appendix (see Table A.2). To visualise how respondents’ perceptions of the politicians’ psychological characteristics and their general competence to function in politics vary according to respondents’ level of disagreement with politicians’ policy positions, marginal effect plots are presented in Figure 1.

Marginal Effects of Disagreement on Affective Polarisation (Measured as the Perceived Psychological Characteristics of the Presented Politicians) *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001 – Plots based on regression models presented in Appendix (Table A.2)

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001 – Plots based on regression models presented in Appendix (Table A.2) The regression models in Table A.2 clearly show that respondents’ level of disagreement with politicians’ policy positions significantly affects their evaluation of all politicians’ psychological characteristics and their perceived general competence to function in politics (p < 0.001). All but one of the coefficients are negative, implying that the more one disagrees with a politician’s policy positions, the more negatively one perceives this politician in terms of ambition, trustworthiness, leadership, general competence, flexibility and so on, which is also confirmed in the marginal effect plots (Figure 1). For hardness, we find an inverse effect suggesting that the more respondents disagree with a politician’s viewpoints, the harder this politician is perceived to be. This could be due to the fact that being hard is not considered to be a positive characteristic in general, hereby thus also indicating respondents’ dislike of politicians they disagree with. These findings clearly demonstrate patterns of vertical affective polarisation in the Belgian context, thereby confirming H1 stating that voters will associate negative traits with politicians they disagree with.

Looking at the other independent and control variables in the models (see Table A.2 in the Appendix), we see that they also play a significant role in shaping evaluations. However, disagreement is by far the variable with the strongest effect. Also for the ideological direction of politicians’ policy positions (outspoken leftist vs. outspoken rightist), the nature of the issue domain discussed in the policy position (Defence, Childcare and Climate) and the ideological positioning of the respondents, statistically significant effects could be uncovered for some characteristics. Gender dissimilarity seems to matter little. Being of a different gender only reaches statistical significance in the trustworthiness model, implying that respondents consider politicians of the different gender as less trustworthy compared to politicians of the same gender (p = 0.012).5.2 The Moderating Effect of Gender Dissimilarity and Stereotyping

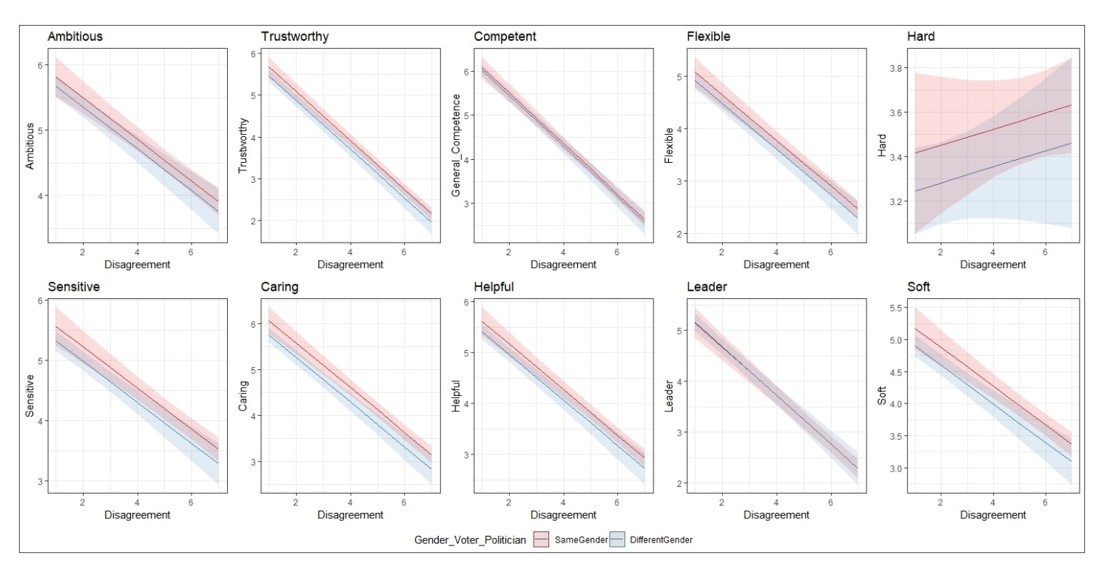

In order to come to a better understanding of the moderating effect of gender dissimilarity on voters’ evaluation of the characteristic traits of politicians they disagree with (RQ2), we ran a number of additional linear regression models including interactions between respondents’ level of agreement and whether they are of the same gender as the presented politician. The full regression models can be found in the Appendix (see Table A.3). Looking at the interaction effects, we see that only (marginally) statistically significant results could be found for sensitive (p = 0.062), soft (p = 0.049), caring (p = 0.035) and helpful (p = 0.054), implying that respondents perceive politicians of the opposite gender with whom they disagree as less sensitive, soft, caring and helpful than politicians’ of the same gender with whom they disagree. For the other psychological characteristics and perceived general competence, the interaction effects did not reach statistical significance. Looking at the other variables included in the models, disagreement again has a very strong (negative) statistically significant effect on respondents’ evaluation of the psychological characteristics and perceived general competence of the presented politicians. Also for the nature of the issue domain (Defence, Childcare and Climate) statistically significant effects could be uncovered.

However, interpreting the results based on regression coefficients alone tells only one part of the story. Therefore, predicted values were computed (see plots in Figures 2). As these predicted value plots show parallel lines with overlapping confidence intervals, the effects cannot be considered statistically significant, which leads us to reject H2: voters do not evaluate the psychological traits of politicians of the opposite gender they do not agree with more negatively compared to politicians of the same gender they disagree with.Predicted Values for Perceived Psychological Characteristics – Gender Dissimilarity Note: All covariates were held at the mean – 95% Confidence Intervals.

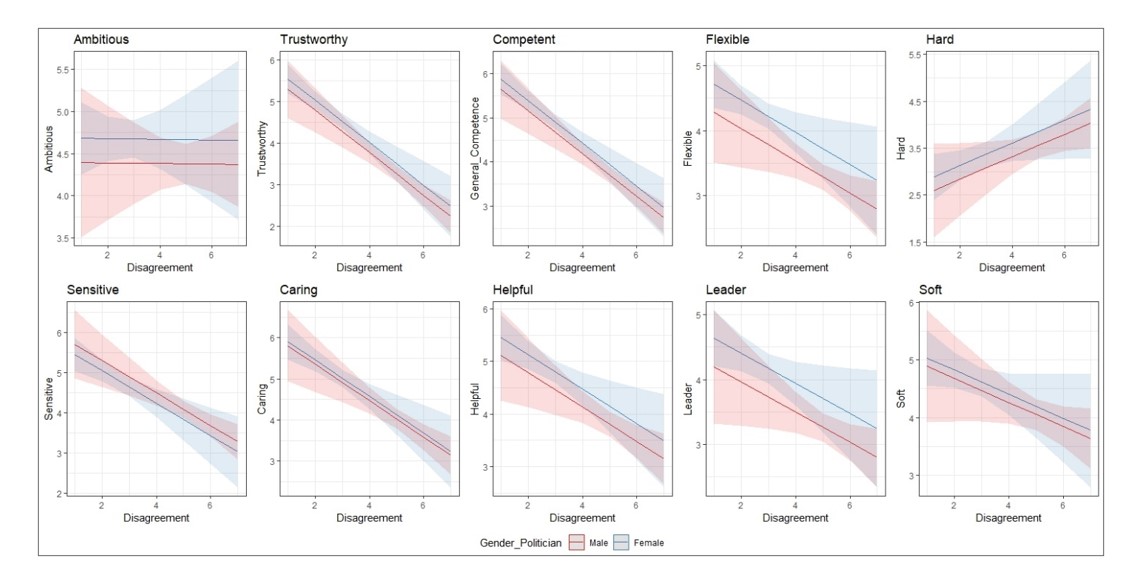

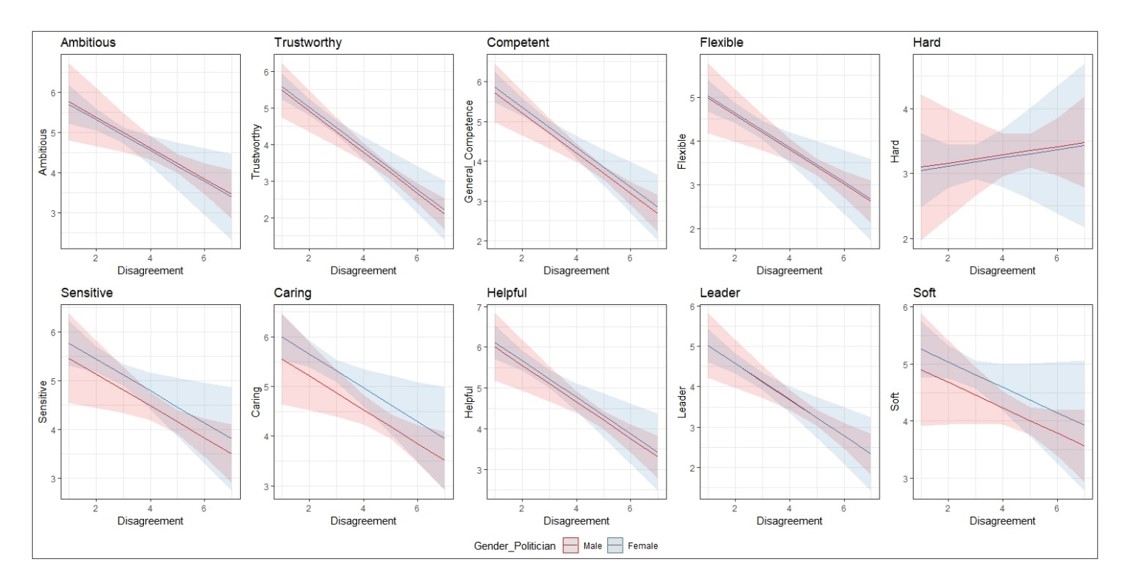

Note: All covariates were held at the mean – 95% Confidence Intervals. Furthermore, we ran a number of regression models to test whether voters more negatively evaluate female politicians proclaiming policy positions they disagree with for hard-policy topics compared to male politicians proclaiming similar policy positions (and vice versa for soft-policy topics) (RQ3). As the central focus of the analyses presented below concerns whether voters evaluate politicians they disagree with differently depending on the gender of the politician and the nature of the policy issue they are referring to, we rely on subsamples including only the results for the Defence (hard policy) and Childcare (soft policy) treatment. To grasp the (potential) moderating effect of politicians’ gender, an interaction between respondents’ level of agreement and the gender of politician was included in the models. The full regression models can be found in the Appendix (see Tables A.4 and A.5).12xFor sake of clarity and transparency, we also provide the full regression table for Climate in the Appendix (see Table A.6). In general, these models mirror the previously presented models in the sense that disagreement has a very strong (negative) statistically significant effect on respondents’ evaluation of the psychological characteristics and perceived general competence of the presented politicians. Also the ideological orientation of the presented policy positions (outspoken leftist vs. outspoken rightist) significantly adds to the models. When it comes to the interaction effects, they do not reach statistical significance in the models for Childcare. Looking at the models for Defence, a number of statistically significant interaction effects emerge, implying that respondents perceive female politicians presenting policy positions for Defence with which they disagree as less ambitious (p = 0.039), less flexible (p = 0.037) and less strong leaders (p = 0.035) compared to their male counterparts. However, as the predicted values plots presented in Figures 3 and 4 again show parallel lines and overlapping confidence intervals, we have to reject H3a and H3b.

Predicted Values for Perceived Valence Characteristics – Defence Note: All covariates were held at the mean – 95% Confidence Intervals. Predicted Values for Perceived Valence Characteristics – Childcare

Note: All covariates were held at the mean – 95% Confidence Intervals. Predicted Values for Perceived Valence Characteristics – Childcare Note: All covariates were held at the mean – 95% Confidence Intervals.

Note: All covariates were held at the mean – 95% Confidence Intervals. -

6 Conclusion

This article focused on the prevalence of vertical affective polarisation (i.e. between citizens and politicians) in the multi-party consociational context of Belgium, and the potential moderating role of politicians’ gender in the relationship between (ideological) disagreement and vertical affective polarisation (operationalised through perceived personality traits). Our findings indicate that disagreement has a very strong and significant effect on voters’ evaluations of politicians’ psychological traits. These results are consistent with existing literature on affective polarisation, which highlights that affective biases can distort perceptions of out-group members (Iyengar et al., 2019). Our results also contribute to the broader discussion on affective polarisation in multi-party systems. While much of the literature has focused on two-party systems like the US (Iyengar et al., 2012), our study, situated in the context of a multi-party democracy, aligns with recent research in multi-party systems (Harteveld, 2021; Reiljan, 2020; Wagner, 2021) which argues that affective polarisation can exist even when political identities are less clear-cut. Even in a least-likely case (a multi-party setting with rather low levels of partisanship and with a tradition of consociationalism and power-sharing), animosity between voters and other-minded politicians is outspoken. These findings highlight that disagreement is a powerful force in shaping voters’ perceptions, even overshadowing political actors’ other characteristics: when voters disagree with a politician, voters hold negative evaluations of that politician’s psychological traits in any case, no matter what the gender of that politician is and whether or not it aligns with certain stereotypes. As such, disagreement seems to overtrump all other effects. This comparative perspective highlights the pervasiveness of affective polarisation across political systems and suggests that emotional biases may function similarly despite differences in party structures.

Furthermore, we did not find any significant moderating effect of politicians’ gender on the relationship between (ideological) disagreement and vertical affective polarisation: voters do not evaluate other-minded politicians with a different gender (gender dissimilarity) more negatively than other-minded politicians with the same gender; nor do they do this for other-minded politicians defending a position on an issue for which they are stereotypically not considered competent (such as women taking positions on defence issues). The lack of a moderating effect could potentially be explained by the fact that gender identity is not salient enough in the Belgian ‘gender-neutral’ society (Meier, 2012) to yield large effects. This can be linked to the strong institutionalisation of gender in political life, with legally binding gender quotas (Devroe et al., 2020) and a high share of female representatives in parliament and government. Flemish voters have been intensively exposed in the last decades to female politicians taking up prominent roles, which makes gender less salient. An alternative explanation could be that, similar to the US (Klar, 2018), gender identity is conceived differently along party lines rendering the cohesiveness of this category not powerful enough to overtrump feelings based on differences in policy positions. The question thus arises whether the effect of dissimilarity would be larger when it comes to other socio-demographic identity categories related to, for example, ethnic origin, age or level of education.

We end by suggesting four avenues for further research. In the experimental study, two very outspoken profiles were presented to our respondents: a clearly rightist profile and a similar leftist profile, leading to strong affective reactions. Future research could usefully investigate whether the same affective reactions would appear when respondents are confronted with a more centrist profile. Disagreement is possible for this kind of profile, as well, but it remains to be seen whether it would result in the same negative evaluation and whether disagreement would also overtrump all other effects. Another suggestion for further research is to operationalise affective polarisation in a different manner. We focused on the evaluation of personality traits of politicians, but there are other kinds of operationalisation possible, including thermometer scores or indicators capturing social distance (see also the ‘Methodology’ section in this article). Testing whether the same results would come forward when these other indicators are used could yield important new insights on how to effectively measure and operationalise affective polarisation. Third, we focused on gender as potential moderating factor, but (as suggested just above) there are other socio-demographic variables that could temper or reinforce negative feelings based on ideological disagreement. In addition, sociocultural factors, such as hobbies, cultural tastes and sports participation, could moderate the evaluation of politicians one disagrees with, which would be worth further exploring. Finally, there is the evident suggestion to study the moderating impact of gender in other contexts: either in other political systems that are less gender-equal than Belgium, or among specific subgroups in the population (such as old, lower-educated men, or radical right voters) for which gender constitutes an identity marker that could evoke negative feelings.

Taken together, these suggestions for further research could help provide a more coherent picture of the prevalence of vertical affective polarisation and potential moderating factors. References Abramowitz, A. I., & Webster, S. (2016). The Rise of Negative Partisanship and the Nationalization of U.S. Elections in the 21st Century. Electoral Studies, 41, 12-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2015.11.001.

Bankert, A., Huddy, L., & Rosema, M. (2017). Measuring Partisanship as a Social Identity in Multi-party Systems. Political Behavior, 39(1), 103-132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9349-5.

Bantel, I. (2023). Camps, Not Just Parties. The Dynamic Foundations of Affective Polarization in Multi-party Systems. Electoral Studies, 83, 102614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2023.102614.

Bauer, N. M. (2015). Emotional, Sensitive, and Unfit for Office? Gender Stereotype Activation and Support Female Candidates. Political Psychology, 36(6), 691-708. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12186.

Bernaerts, K., Blanckaert, B., & Caluwaerts, D. (2023). Institutional Design and Polarization. Do Consensus Democracies Fare Better in Fighting Polarization than Majoritarian Democracies? Democratization, 30(2), 153-172.

Bogardus, E. S. (1933). A Social Distance Scale. Sociology & Social Research, 17, 265-271.

Bolce, L., & De Maio, G. (1999). The Anti-Christian Fundamentalist Factor in Contemporary Politics. Public Opinion Quarterly, 63(4), 508-542. https://doi.org/10.1086/297869.

Bolsen, T., & Thornton, J. R. (2021). Candidate and Party Affective Polarization in U.S. Presidential Elections: The Person-negativity Bias? Electoral Studies, 71, 102293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102293.

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The Social Self: On being the Same and Different at the Same Time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(5), 475-482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167291175001.

Burrell, B. C. (1995). A Woman’s Place is in the House: Campaigning for Congress in the Feminist Era. University of Michigan Press.

Casal Bértoa, F., & Rama, J. (2021). Polarization: What Do We Know and What Can We Do About It? [Original Research]. Frontiers in Political Science, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.687695

Dalton, R. J. (2021). Modeling Ideological Polarization in Democratic Party Systems. Electoral Studies, 72, 102346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102346.

Dassonneville, R. (2018). Electoral Volatility and Parties’ Ideological Responsiveness. European Journal of Political Research, 57(4), 808-828. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12262.

Devroe, R., Erzeel, S., & Meier, P. (2020). The Feminization of Belgian Local Party Politics. Politics of the Low Countries, 2(2), 169-191. https://doi.org/10.5553/PLC/258999292020002002004.

Devroe, R., & Wauters, B. (2018). Political Gender Stereotypes in a List-PR System with a High Share of Women MPs: Competent Men versus Leftist Women? Political Research Quarterly, 71(4), 788-800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912918761009.

Dolan, K. (2014). Gender Stereotypes, Candidate Evaluations, and Voting for Women Candidates What Really Matters? Political Research Quarterly, 67(1), 96-107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912913487949.

Druckman, J. N. (2004). Priming the Vote: Campaign Effects in a US Senate Election. Political Psychology, 25(4), 577-594.

Druckman, J. N., & Levendusky, M. S. (2019). What Do We Measure When We Measure Affective Polarization? Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(1), 114-122. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz003.

Fiorina, M. P., Abrams, S. A., & Pope, J. C. (2008). Polarization in the American Public: Misconceptions and Misreadings. The Journal of Politics, 70(2), 556-560. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002238160808050X.

Fiske, S. T., & Neuberg, S. L. (1990). A Continuum of Impression Formation, from Category―Based to Individuating Processes: Influences of Information and Motivation on Attention and Interpretation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 23, 1-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60317-2.

Funk, C. L. (1997). Implications of Political Expertise in Candidate Trait Evaluations. Political Research Quarterly, 50(3), 675-697. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591299705000309.

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Anastasio, P. A., Bachman, B. A., & Rust, M. C. (1993). The Common Ingroup Identity Model: Recategorization and the Reduction of Intergroup Bias. European Review of Social Psychology, 4(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779343000004.

Garrett, R. K., Gvirsman, S. D., Johnson, B. K., Tsfati, Y., Neo, R., & Dal, A. (2014). Implications of Pro- and Counterattitudinal Information Exposure for Affective Polarization. Human Communication Research, 40(3), 309-332. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12028.

Harteveld, E. (2021). Fragmented Foes: Affective Polarization in the Multiparty Context of the Netherlands. Electoral Studies, 71, 102332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102332.

Hobolt, S. B., Leeper, T. J., & Tilley, J. (2021). Divided by the Vote: Affective Polarization in the Wake of the Brexit Referendum. British Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 1476-1493. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000125.

Huddy, L. (2001). From Social to Political Identity: A Critical Examination of Social Identity Theory. Political Psychology, 22(1), 127-156. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00230.

Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993). Gender Stereotypes and the Perception of Male and Female Candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37, 119-147. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111526.

IPU. (2021, 1 January 2021). Global and Regional Averages of Women in National Parliaments. Retrieved 4 February 2024, from https://data.ipu.org/women-averages.

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 129-146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, Not Ideology: A Social Identity Perspective on Polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405-431. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs038.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and Loathing across Party Lines: New Evidence on Group Polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690-707. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12152.

Jacobsmeier, M. L. (2014). Racial Stereotypes and Perceptions of Representatives’ Ideologies in US House Elections. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 39(2), 261-291. https://doi.org/10.1111/lsq.12044.

Klar, S. (2018). When Common Identities Decrease Trust: An Experimental Study of Partisan Women. American Journal of Political Science, 62(3), 610-622. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12366.

Krook, M. L., & O’Brien, D. Z. (2012). All the President’s Men? The Appointment of Female Cabinet Ministers Worldwide. The Journal of Politics, 74(3), 840-855. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381612000382.

Kunda, Z., & Thagard, P. (1996). Forming Impressions from Stereotypes, Traits, and Behaviors: A Parallel-Constraint-Satisfaction Theory. Psychological Review, 103(2), 284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.103.2.284.

Kundra, Z., & Sinclair, L. (1999). Motivated Reasoning with Stereotypes: Activation, Application, and Inhibition. Psychological Inquiry, 10(1), 12-22. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1001_2.

Lammers, J., Gordijn, E. H., & Otten, S. (2009). Iron Ladies, Men of Steel: The Effects of Gender Stereotyping on the Perception of Male and Female Candidates Are Moderated by Prototypicality. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39(2), 186-195. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.505.

Lelkes, Y. (2021). Policy over Party: Comparing the Effects of Candidate Ideology and Party on Affective Polarization. Political Science Research and Methods, 9(1), 189-196. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.18.

Levendusky, M. S., & Malhotra, N. (2016). (Mis)perceptions of Partisan Polarization in the American Public. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 378-391. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfv045.

Lijphart, A. (1969). Consociational Democracy. World Politics, 21(2), 207-225. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009820.

Luttig, M. D. (2017). Authoritarianism and Affective Polarization: A New View on the Origins of Partisan Extremism. Public Opinion Quarterly, 81(4), 866-895. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfx023.

Marien, S., Schouteden, A., & Wauters, B. (2017). Voting for Women in Belgium’s Flexible List System. Politics & Gender, 13(2), 305-335. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X16000404.

Mason, L. (2015). ‘I Disrespectfully Agree’: The Differential Effects of Partisan Sorting on Social and Issue Polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 128-145. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12089.

McConnell, C., Margalit, Y., Malhotra, N., & Levendusky, M. (2018). The Economic Consequences of Partisanship in a Polarized Era. American Journal of Political Science, 62(1), 5-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12330.

McDermott, M. L. (2009). Religious Stereotyping and Voter Support for Evangelical Candidates. Political Research Quarterly, 62(2), 340-354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912908320668.

Meier, P. (2012). From Laggard to Leader: Explaining the Belgian Gender Quotas and Parity Clause. West European Politics, 35(2), 362-379. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2011.648011.

Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., & Torres, M. (2018). How Conditioning on Posttreatment Variables Can Ruin Your Experiment and What to Do About It. American Journal of Political Science, 62(3), 760-775. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12357.

Ondercin, H. L., & Lizotte, M. K. (2021). You’ve Lost that Loving Feeling: How Gender Shapes Affective Polarization. American Politics Research, 49(3), 282-292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X20972103.

Reiljan, A. (2020). ‘Fear and Loathing across Party Lines’ (also) in Europe: Affective Polarisation in European Party Systems. European Journal of Political Research, 59(2), 376-396. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12351.

Rice, M. G., Remmel, M. L., & Mondak, J. J. (2021). Personality on the Hill: Expert Evaluations of US Senators’ Psychological Traits. Political Research Quarterly, 74(3), 674-687. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912920928587.

Robison, J., & Moskowitz, R. L. (2019). The Group Basis of Partisan Affective Polarization. The Journal of Politics, 81(3), 1075-1079. https://doi.org/10.1086/703069.

Rogowski, J. C., & Sutherland, J. L. (2016). How Ideology Fuels Affective Polarization. Political Behavior, 38(2), 485-508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9323-7.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Gender Stereotypes and Vote Choice. American Journal of Political Science, 46(1), 20-34. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088412.

Sears, D. O. (1983). The Person-positivity Bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(2), 233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.2.233.

Somer, M., & McCoy, J. (2018). Déjà vu? Polarization and Endangered Democracies in the 21st Century. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(1), 3-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218760371.

Tajfel, H. T. C. (1979). An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 33-48). Brooks/Cole.

Timmermans, A. (2017). High Politics in the Low Countries: An Empirical Study of Coalition Agreements in Belgium and the Netherlands. Routledge.

Turner, J. C. (1987). Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-categorization Theory. Basil Blackwell.

van Erkel, P. F., & Turkenburg, E. (2022). Delving into the Divide: How Ideological Differences Fuel Out-party Hostility in a Multi-party Context. European Political Science Review, 14(1), 386-402.

Van Trappen, S., Devroe, R., & Wauters, B. (2020). It is All in the Eye of the Beholder: An Experimental Study on Political Ethnic Stereotypes in Flanders (Belgium). Representation, 56(1), 31-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2019.1679240.

Wagner, M. (2021). Affective Polarization in Multiparty Systems. Electoral Studies, 69, 102199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102199.

Westwood, S. J., Iyengar, S., Walgrave, S., Leonisio, R., Miller, L., & Strijbis, O. (2018). The Tie that Divides: Cross-national Evidence of the Primacy of Partyism. European Journal of Political Research, 57(2), 333-354. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12228.

Noten

-

1 Druckman and Levendusky (2019) distinguish four ways to measure affective polarisation in surveys (see later). We link here to their second and third approach by asking respondents to assess the psychological traits of politicians, including their level of trustworthiness. As such, we take negative evaluations of politicians’ perceived psychological characteristics as an indicator of affective polarisation.

-

2 There is, however, an on-going debate over the extent of such ideological polarisation. We do not aim to take position in this debate, but we rather argue that while there are important connections between affective and ideological polarisation (Abramowitz & Webster, 2016), we consider them as theoretically and empirically distinct concepts. Hence, in this article, we focus exclusively on the affective dimension of polarisation (and not so much on ideological polarisation).

-

3 This categorisation is, furthermore, based on an extensive review of 16 international studies on the assignment of policy issues to men and women by three key actors, that is, (mass) media, voters and party elites, and we also checked the appointment of Flemish male and female ministers to these issue domains (Devroe & Wauters, 2018).

-

4 Pilot tests of the experimental design (among student samples) confirmed that the ideological orientation of the various policy positions was sufficiently clear and interpreted as outspoken leftist or rightist.

-

5 The incorrect answers are more or less equally spread over the different issue domains and over the different politician’s profiles (male or female, outspoken leftist or rightist). The percentage of incorrect answers ranges from 0.80% to 6.00% for all 12 presented profiles. Because of the risk of a selection effect, we made a comparison between the final sample and respondents who could not answer the manipulation check correctly. These groups do not differ substantially on important aspects. There is a small selection bias in that our final sample is slightly younger, but there are no outspoken differences concerning gender and level of education.

-

6 Although it is difficult to determine how well the online panel members represent the general population, we tried to maximise their representativeness. We set several quotas: a hard quota for the gender of the respondents and soft quotas for their age and level of education. In addition, our sample was weighted for gender and age (weighting factors ranging from 0.79 to 1.14).

-

7 The other invitations were apparently sent to invalid or outdated email addresses.

-

8 A power analysis confirms that our analyses are sufficiently powered with this sample (see Appendix).

-

9 To test the robustness of our results, separate analyses (available upon request) were performed for those respondents (4) that could find out the purpose of the research and so-called speeder-respondents (51) who completed the survey faster than half the median completion time. However, the results of these analyses are in line with the results for the full sample, which adds to the robustness of our findings. Therefore, no additional respondents were excluded.

-

10 It is important to note that certain traits can have multiple interpretations. ‘Ambitious’, for example, might be seen positively as a sign of drive and determination by some respondents, while others might perceive it negatively as self-serving or overly aggressive. ‘Soft’ might be viewed positively as empathetic and considerate, or negatively as weak and indecisive. Similarly, ‘hard’ can be interpreted positively as strong and resolute, or negatively as harsh and unyielding.

-

11 In order to ensure the robustness of our findings, we conducted several additional analyses. First, we introduced disagreement as a dummy variable, confirming the results of our analyses when disagreement was treated as a continuous variable (see Tables A.7-A.10 in the Appendix). Second, we performed subsample analyses based on the respondents’ political orientation (left or right; see Tables A.11-A.16 in the Appendix), gender (male or female; see Tables A.17-A.22 in the Appendix) and whether they agreed or not with the presented policy positions (see Tables A.23-A.28 in the Appendix). These analyses reaffirm our findings, showing little to no significant interaction effects.

-

12 For sake of clarity and transparency, we also provide the full regression table for Climate in the Appendix (see Table A.6).