Exploring Mediating Motivations for Muslims’ Electoral Preferences

-

1 Introduction

This Special Issue explores the political incorporation of migrants from different perspectives. One of these is their electoral choices but also the underlying motivations. Previous studies found migrants to often vote for parties on the left and as well as for candidates reflecting their own ethnic and/or socio-economic background, but why do they do this? In this respect, one often focuses on the fact that migrants belong to ethnic minorities, assuming that this characteristic is especially conducive to under-representation. Yet we will highlight another related characteristic that in post-9/11 times may even function as a stronger social marker of the ‘otherness’ of migrants, namely that many Europeans with a migration background are (religious) Muslims (Helbling & Traunmüller, 2020).

The political representation of ethnic minorities has been extensively studied in Europe, focusing mainly on the supply of ethnic minority candidates on party lists and their election (Sobolewska, 2014; Togeby, 2008). In general, these studies conclude that ethnic minorities are under-represented in elected bodies. Similarly, minorities’ political participation has received scholarly attention, revealing ethnic minorities’ lower voter turnout (Cesari, 2014; Van Heelsum et al., 2016), the leftist party preference (Azabar & Thijssen, 2020a; Jacobs et al., 2004; Swyngedouw et al., 2015) and – rather exceptionally – the preference for ethnic minority candidates (i.e. the ethnic vote) and Muslim candidates (i.e. the Muslim vote) in urban cities (Azabar & Thijssen, 2021; Teney et al., 2010).

Currently, scholars still rely mainly on (macro-level) aggregated data to explain the electoral choices of Muslims in West Europe. For instance, scholars generally discard religious motivations as crucial factors for Muslims’ party vote on the assumption of the secular leftist vote (Amjahad & Sandri, 2012; Castano, 2014), while others claim that Muslims’ precarious socio-economic background and experiences with discrimination serve as an explanatory factor (Cesari, 2014; Zibouh, 2013). But it goes without saying that these contextual inferences are sub-optimal because of the imminent risk of ecological fallacy. Also, less is known as to why Muslims are more likely than non-Muslims to vote preferential (Azabar & Thijssen, 2020b). Clearly, scholarship explaining minorities’ electoral preferences is still in its infancy in Europe, with a few notable exceptions focusing on the party level (see Bergh & Bjorklund, 2011; Goerres et al., 2021; Sanders et al., 2014). This article aims to contribute to the literature on minorities’ political integration by explaining Muslims’ electoral choices in Belgium, a flexible proportional system where voters can vote either for a party list (and thus agree with the order of the candidate list as presented) or for one or more candidates on a single party list.

But why should we study Muslims’ electoral choices specifically? First, scholars have acknowledged the revival of religion in West European societies (in particular, Islam), which contradicts the secularization thesis, which claims that religion would play a more marginal role in modern societies (Berger, 1999; Habermas, 2008). Second, although previous studies focus mostly on ethnicity as a salient identity marker instead of religion, scholars emphasize how ethnicity and religion are intertwined (Fleischmann et al., 2011; Zibouh, 2013). Moreover – in a post-9/11 era – research claims that the salience of Muslims’ religious identity seems to have risen above that of their ethnic background (Dancygier, 2014; Voas & Fleischmann, 2012), referring to this phenomenon as the ‘ethnicization of Islam’ (Fadil et al., 2015). Accordingly, scholars argue that the development of a distinct Muslim identity in the electoral arena (Peace, 2015: 3), the increased public scrutiny following terrorist attacks (Dancygier, 2014: 14) and the collective history of being stigmatized as the ‘other’ (Peucker, 2016) warrant studies on Muslims’ political agency and integration in western societies. Lastly, Fadil et al. (2015) have referred to the increasing demographic presence and growth of Muslims in Belgium turning them into an important political force. Hence, despite the increasing impact of Muslims on electoral outcomes, little systematic research is available explaining, on the one hand, their party vote and, on the other hand, casting a preferential vote.

Drawing on exit poll data of the local elections of 2018 in Belgium and in-depth interviews with seventeen Muslims, we aim to explain the motives behind Muslims’ electoral choices, notably their tendency to vote leftist and to cast preferential votes, compared with non-Muslims (RQ). On the one hand, we depart from the idea that the same theories explaining non-Muslims’ electoral choices, notably the Michigan model (party evaluation, issues and candidates), can also explain Muslims’ electoral preferences. On the other hand, studies have pointed to the saliency of minorities-specific motivations (see Goerres et al., 2021). Owing to the politicization of Islam and studies pointing to the salience of religious politics among Muslims (Elshayal, 2018; Modood, 2003), we also account for religious issues as an explanatory variable as well as political alienation because the marginalization and exclusion of Muslims could lead to political alienation (Taush, 2019). This study goes beyond assumptions for minorities’ political behaviour by focusing on Muslims’ self-declared motivations of electoral preferences and thus Muslims’ political agency. Because we rely on self-reported motives based on an open-ended question – which may be conducive to post-rationalization – we complement our quantitative survey research with in-depth interviews with Muslims to further unravel their political choices and decision-making process.

In this article, we aim to contribute to the scant literature explaining the electoral motivations of Muslims with respect to their party vote, on the one hand, and preferential vote, on the other. In order to examine this, we look at the Belgian local elections of 2018. As one of the smaller countries in Europe, with an estimated 7.6% Muslims (Pew Research Center, 2017a), Belgium is an interesting case to study Muslims’ electoral preferences owing to the compulsory voting, its flexible proportional system and the extensive choices on both the party and candidate levels. In addition, the Muslim population in Belgium consists of, primarily, first generation and their offspring with a Moroccan and Turkish background sharing a similar profile owing to their migration experiences. However, this does not mean that Muslims are an undifferentiated group, but rather that we look at Muslims as a separate political category, acknowledging its limitations (Dancygier, 2014; Peace, 2015). Thus, we do not consider Muslim to necessarily mean: a religious identity, but instead an identity that may have religious, racial, political or cultural dimensions (Sinno, 2012). To put it more clearly, those citizens who identify themselves as Muslims – regardless of the extent of religious practice – are defined as such.

We find that the reason why Muslims disproportionally vote for leftist parties is somehow driven by their stronger preoccupation with particular issues than by party evaluation motives, vis-à-vis non-Muslims. However, the other mediators, notably religious issues, political alienation and candidates do not explain the massive support of Muslims for leftist parties. Nevertheless, the size of the mediating effects of issues is rather small. Interestingly, the direct effect of belonging to the Muslim group on left vote remains strong despite the several mediators and controls in the model. Second, with regard to casting a preferential vote, we find that Muslims indeed vote more preferential than non-Muslims. Yet, interestingly, we do not find any significant mediating factors, either of the Michigan model or of the more minorities’ specific factors (religious issues and political alienation). -

2 Electoral Preferences of Muslims: A Low Turnout, a Leftist Party Vote and a Preference for Muslim Candidates

Several studies have revealed that Muslims’ political participation is characterized by a lower electoral turnout,1x In countries without compulsory voting. a preference for left-wing political parties and Muslim candidates, particularly in urban cities with a sizeable Muslim electorate (Azabar & Thijssen, 2021; Cesari, 2014; Teney et al., 2010; Van Heelsum et al., 2016). Notwithstanding this geographical concentration, most Muslim voters have intended to vote for established mainstream leftist parties. For instance, in the US the overwhelming majority of Muslim voters cast their votes for Hillary Clinton (75%) in the 2016 presidential elections, while 66% of Muslims state that they identify with or lean towards the Democratic party (Pew Research Center, 2017b). The same goes for UK Muslims, who are a strong Labour constituency: in 2015, 74% of Muslims opted for the Labour party. In 2017, this share has risen to 87% (Curtice et al., 2018). In regard to the French presidential elections in 2007, Dargent (2009) showed that 95% of Muslims voted for Ségolene Royal (Parti Socialiste) compared with only 5% for Sarkozy.

With regard to Belgium, most electoral studies are conducted in the capital of Belgium, Brussels, owing to the presence of a sizeable Muslim electorate.2x Approximately 25% of Brussels inhabitants are Muslim (Zibouh, 2013). Zibouh’s (2013) overview of electoral studies in the French-speaking part of Belgium confirms the leftist vote. Based on exit poll data gathered at the regional election of 2004 in Brussels, 46% of Muslims voted for the Parti Socialiste, while 13% voted for the Liberal party (MR) and 7% for the Christian Democrats (cdH) (Sandri & De Decker, 2008). A similar pattern of results was found at the federal elections in 2007 (Amjahad & Sandri, 2012), despite major scandals of financial fraud concerning politicians belonging to the Parti Socialiste.3x 43% of Muslims voting for Parti Socialist, 11% for the Greens, 19% for cdH and 15% for MR.

More recently, a few studies have focused on the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, Flanders, revealing the variation in the leftist vote of Muslims (Azabar & Thijssen, 2020a; Swyngedouw et al., 2015). At the local elections of 2018, on an aggregate level, 60.3% of Muslims (compared with 36% non-Muslims) voted for a traditional leftist party: a third for the Socialist Democrats, 15% for the radical left and 11% for the Green party (Azabar & Thijssen, 2020a). Interestingly, when distinguishing among the several regions in Belgium, Muslims in Flanders voted less traditional left (52.1%) than did their Brussels (62.7%) and Walloon (70.7%) counterparts (see Table 1). Hence, not only non-Muslims in Flanders but also Muslims vote more rightist than their fellow citizens in Brussels and Wallonia. All in all, we can conclude that Muslims’ party preference may differ regionally and that more variation in the leftist Muslim vote occurs in the Flemish region (Azabar & Thijssen, 2020a).Table 1 Party family choice of Muslims and non-Muslims at the local elections of 2018 in Belgium according to region (N = 4511)Party choice Muslims (N = 462) Non-Muslims (N = 4049) Blank 6.7 4 Local parties 13.2 20.4 Social Democrats 34.8 15 Greens 10.6 14.7 Radical Left 14.9 5.7 Liberals 3.9 8.5 Christian Democrats 11.3 12.2 Nationalists 3.2 14.6 Radical right 0.4 3.5 100 % 100 % Source: Azabar & Thijssen (2020a)

Contrary to the case concerning Muslims’ party vote, less research has been conducted on the preferential vote(s) of Muslims, let alone on their motivations to vote preferential. The scant research on Muslims’ preferential votes has shown that Muslim voters are more likely to vote preferential than non-Muslims in Antwerp, the largest city of Belgium (Azabar et al., 2020b), and for Muslim candidates (Azabar et al., 2020b; Heath et al., 2015). Interestingly, scholars have pointed to preferential voting as a sophisticated way of voting (André et al., 2012). However, Muslims’ group consciousness and strong social identity could compensate for the lack of political resources among members of ‘deprived’ groups (Miller et al., 1981). Hence, a possible explanation lies in their precarious situation and the under-representation of their interests, triggering Muslims to vote more preferential to obtain a fairer representation and policy. These preferential votes could contribute to Muslims’ descriptive and substantive representation in policymaking institutions, increasing the sense of inclusion in the political system (Dancygier, 2014).

-

3 Muslims’ Motivations for Electoral Choices

We aim to explain, first, Muslims’ tendency to vote for a left party and, second, vote preferential with the Michigan model as it is one of the most commonly used theoretical approaches to explaining voting behaviour in established democratic countries (Goerres et al., 2021). We are aware that Campbell et al. (1960) initially developed the funnel of causality to explain party voting in the US and that more fine-grained models have been developed to explain preferential voting in European PR systems (e.g. André et al., 2012). Yet we argue that the basic explanatory categories of the funnel of causality (party evaluation, candidate evaluation, issues) may also provide useful insights for preferential voting because in the Belgian electoral system, a preference vote is ipso facto a second-order choice in the sense that one first has to select the preferred party in order to obtain its candidate list. This resonates with authors such as Dalton (2014: 184), who have demonstrated that the Michigan model can also be used to explain vote choices in general and not just party voting. Second, we will deal with Muslim-specific factors such as religious issues and distinguish them from other issues because of the specificity of a Muslim vote, next to political alienation, as an explanation for Muslims’ electoral choices.

3.1 Explaining Party Preferences with the Michigan Model

3.1.1 Party Evaluation

The Michigan model has been commonly used to successfully explain party vote for the majority group. As a theory of vote choice, the Michigan model centres on partisanship designed as a psychological affinity with a political party, referred to as party identification (Campbell et al., 1960). Attachment to a party is thus acquired through a socialization process that assumes a stable and lasting relationship with a political party. Yet Rosema (2006) has convincingly argued that in European PR systems party identification is less stable and more evaluative, using the term party evaluation. Subsequently, once voters positively identify with a party – as a long-term factor – it can shape attitudes towards candidate choice and issue preferences as short-term factors (Goerres et al., 2021; Rosema, 2006). Factors that influence party choice can therefore possibly shape candidate choice. In this article, we depart from the notion that the Michigan model can also explain minorities’ party choice, in particular when it concerns the short-term factor such as candidates or issues (see Bergh & Bjorklund, 2011). However, researchers have argued that voters who vote on the basis of party evaluation tend to be politically sophisticated (Campbell et al., 1960; Goerres et al., 2021; Rosema, 2006). Owing to the low political knowledge and interest among Muslims, we argue that the explanatory effect of party evaluation for Muslims does not explain the leftist vote among Muslims vis-à-vis non-Muslims (Van der Eijk & Niemöller, 1987).

H1a Party evaluation does not explain Muslims’ (leftist) party preference, vis-à-vis non-Muslims.

As voters first choose their preferred party and subsequently cast a list or preferential vote (André et al., 2017), we also account for the mediator left vote when explaining Muslims’ preferential voting behaviour. One can assume that ideological voters are more likely to refrain from preferential voting as they would agree with the list presented by the party. As we hypothesized (H1a) that Muslims do not vote according to party evaluation motives, the latter also does not explain whether they cast a preferential vote or not, compared with non-Muslims. We thus hypothesize the following:

H1b Party evaluation does not explain Muslims’ likelihood of casting a preference vote, vis-à-vis non-Muslims.

3.1.1.1 Issues

We further assume that policy issues, as short-term factors traditionally explaining voting behaviour, can also guide Muslims’ political behaviour. Popkin (1991) argues that voters are expected to know which positions parties take with regard to (certain) policy issues. Not all policy issues are considered by the voter but only those they are attracted to. Popkin (1991) talks about issue publics: voters who focus on a certain policy theme and put it first as a decision rule. We hereby do not claim that the same issues are perceived to be important but that issues explain party choice more for Muslims vis-à-vis non-Muslims owing to their marginalized status.

Previous sociological research has taught us that Muslim minorities reside mainly in large cities and are characterized by a relatively precarious status because of systemic exclusion: a low level of education, high unemployment, underprivileged and over-represented in jobs with low qualification requirements and low wages (Fadil et al., 2015; Noppe et al., 2018). Accordingly, Inglehart’s (1977) scarcity hypothesis emphasizes that when scarcity prevails, material needs like hunger and safety will be addressed first. More recently, Zibouh (2013) and Cesari (2014) claim that the electoral choices of Muslims are influenced by motives related to socio-economic and equality issues. The latter refer to Islamophobia and discrimination of Muslims in western countries (Bayrakli & Hafez, 2019). Given the precarious situation of Muslims, we hypothesize that the left-wing preference can be explained by issues influencing their vote choice.H2a Issues explain Muslims’ (leftist) party preference to a higher extent than non-Muslims.

These issues could also influence minorities’ tendency to vote preferential as scholars claim that voters use information shortcuts such as demographic cues to estimate a candidate policy preference (Cutler, 2002; Popkin, 1991). When marginalized voters believe that candidates ‘who are like them’ share similar experiences and will pursue policies that will benefit them (Dancygier, 2014; Mansbridge, 1999), issues could trigger them to vote preferential (André et al., 2017; Azabar et al., 2020b). The under-representation of their interests may activate this specific type of voting pattern to obtain a fairer representation and policy, especially when these issues relate to material/basic needs (Inglehart, 1977).

H2b Issues explain Muslims’ likelihood of casting a preference vote to a higher extent than non-Muslims.

3.1.1.2 Candidates

Thirdly, it is very plausible that voters, in general, are guided by candidates when voting for a party. This could apply, in particular, to local elections, as the chance of a voter knowing a candidate is high (so-called ‘friends and neighbour’ voting, see Górecki & Marsh, 2014). However, political studies have pointed to the under-representation of minorities such as women and ethnic minorities in political bodies (Azabar & Thijssen, 2021; Teney et al., 2010. Moreover, scholars previously claimed that Muslims are more drawn to leftist parties owing to their socio-economic status and the discrimination they experience (Cesari, 2014; Zibouh, 2013). Accordingly, Bergh and Bjorklund (2011) referred to the leftist vote of migrants as a way of group voting, referring to an iron law. We therefore expect Muslims to mention candidate motives when voting for a party, albeit to a lesser extent than non-Muslims, particularly in Belgium, where right-wing candidates are among the most popular candidates.

H3a Candidates explain Muslims’ (leftist) party preference to a lesser extent than non-Muslims.

Furthermore, we could expect voters who choose a party because of candidates to be more prone to cast a preference vote than others. In particular, Muslims residing in social contexts where they are fiercely debated and problematized could be eager to support ‘one of their own’ to represent them in the political arena (Azabar et al., 2020b; Heath et al., 2015). André et al. (2017) argue that under-represented groups are more likely to cast preferential votes for in-group candidates in order to obtain more diverse elected bodies. Second, a symbolic explanatory approach argues that when voters identify themselves as group members, they will support their in-group members more than out-group members (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), in particular, historically marginalized groups, because they have a stronger feeling of identity owing to barriers they face in society (Miller et al., 1981). Sharing a common socio-demographic trait, particularly one that is visible and politically salient, could lead to voters supporting political candidates who are alike (Popkin, 1991). Indeed, Teney et al. (2010) have established that ethnic minorities prefer candidates with an ethnic minority background (ethnic voting). As far as we know, a dearth of studies has pointed to the existence of a Muslim vote: Muslim voters are more likely to vote for Muslim candidates (Azabar et al., 2020b; Heath et al., 2015). In addition, we formulate explorative hypotheses stating that Muslims’ preferential voting can be explained owing to knowing the candidate personally and, to a lesser extent, owing to the competences of the candidate as more political information is required for the latter vis-à-vis non-Muslims.

H3b Candidates explain Muslims’ likelihood of casting a preference vote to a higher extent than non-Muslims.

H3c Knowing a candidate personally explains Muslims’ likelihood of casting a preference vote to a higher extent than non-Muslims.

H3d Competences of a candidate explain Muslims’ likelihood of casting a preference vote to a lesser extent than non-Muslims.

3.2 Explaining Muslims’ Party Preference with Muslims’ Specific Factors

3.2.1 Political Alienation

The political-social discussions about Syrian foreign fighters and terror, next to the usual debates about the headscarf, Islamic schools and ritual slaughter, have rendered Islam the focus of heated and polarized political discussions in which in-group and out-group thinking thrive easily (Bayrakli & Hafez, 2019; Fleischmann et al., 2012). For example, a European report (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2017) found that 1 in 3 European Muslims experienced discrimination in the labour market and that half of the Muslims surveyed encountered obstacles in the housing market. International studies consistently report on the various forms of exclusion and discrimination experienced by Muslims, partly explaining their lower socio-economic status and higher poverty rate (Amnesty, 2012; European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia 2006; Open Society Foundation, 2011). This exclusion could eventually lead to Muslims being politically alienated and thus they would rather opt for ‘exit’ than ‘voice’ as they have few resources (Hirschman, 1970; Verba et al., 1995). Indeed, Muslims generally vote less than non-Muslims in western countries (see Cesari, 2014). However, as voting is mandatory in Belgium, we hypothesize that Muslims will cast a party vote, but not preferential, as they are more politically alienated and will vote merely to avoid potential penalties compared with non-Muslims. Subsequently, we hypothesize that political alienation does not explain the leftist vote or casting a preferential vote vis-à-vis non-Muslims.

H4a Political alienation does not explain Muslims’(leftist) party preference, similar to non-Muslims.

H4b Political alienation does not explain Muslims’ likelihood of casting a preference vote similar to non-Muslims.

3.2.2 Religious Issues

Drawing on the social identity theory of Tajfel and Turner (1979), Verkuyten and Yildiz (2007) further state that group consciousness among Muslims was already strong but may be strengthened in the current context. These findings are in line with the conclusions studying the politicization of the Muslim identity in various Western European urban areas. A strong Muslim identity encouraging young Muslims to take political action (Fleischmann & Phalet, 2012) refers to an identity politics, notably a power struggle by group members who are strongly aware of their religious group membership and who are committed to the interests of the group. Would this phenomenon be limited to more informal forms of participation such as demonstrations and protests? Sanders et al. (2014) state in their study that experiences of (religious) discrimination do shape the political vote choices of British minority groups. The authors argue that discriminated minorities opt for left-wing parties because they represent the interests of minority groups. Modood (2003) further argues that British Muslim voters are encouraged to adopt identity politics in a context that stigmatizes Muslims because of their religious identity and would therefore lean more towards leftist parties. Our fifth hypotheses therefore focuses on religious issues as an explanatory variable, not only on the party level, but the same thought process could lead to hypothesizing that Muslims would vote more preferential owing to religious issues eagerly searching for a Muslim candidate as they could defend their religious interests best.

H5a Religious issues explain Muslims’(leftist) party preference to a higher extent than non-Muslims’ party preference.

H5b Religious issues explain Muslims’ likelihood of casting a preference vote to a higher extent than non-Muslims.

-

4 Data and Method

In order to analyse the electoral preferences of Muslims – notably party vote, on the one hand, and preferential vote, on the other – we conducted an exit poll at the local elections in 2018 and in-depth interviews with Muslims in Belgium. At the local elections, all citizens had to vote owing to the compulsory voting system, although this will not be the case any more from 2024 onwards. Migrants lacking citizenship and living more than five years in Belgium can vote after registering themselves at the municipal council. In what follows we will shed light on the exit poll data and then expatiate on the interviews.

4.1 Exit Poll Data 2018

At the 2018 local elections, we conducted an exit poll in a consortium of six universities (VUB, UHasselt, UGent, UAntwerpen, UNamur and UCL), providing representative and reliable data. The approval of the Ethical Commission has been provided by each university. We randomly sampled 45 municipalities across Belgium where a systematic design was adopted: every fifth voter was asked to participate when leaving the polling station. As ethno-religious minorities tend to participate less in research, we selected six municipalities with a high ethno-religious diversity to oversample nine polling stations by deploying more interviewers in order to get more ethno-religious respondents.4x Antwerpen, Sint-Jans-Molenbeek, Sint-Joost-ten-Node, Charleroi and Luik. The 228 trained pollsters were equipped with tablets to accurately register party and candidate choices using a mock ballot form resembling the design of lists and candidates as seen on their computer screen in the polling booth. Lastly, we invested in diversity among pollsters to obtain a higher response rate among minority groups, lowering the threshold for Muslims to participate. We presented respondents a face-to-face survey (consisting of questions on socio-demographic traits, voting behaviour and political attitudes) together with a mock ballot as a tool to record the multiple preferential voting behaviour in a reliable way. The mock ballot perfectly resembled the design of lists and candidates as seen on their computer screen in the polling booth. This resulted in 4,511 respondents, the majority of whom we identify as non-Muslims (N = 4049), notably those who are not Muslim. Among the respondents, 462 self-identified as Muslim, mostly with a Moroccan or Turkish background, as these minorities are over-represented in Muslim communities.

The motivations to vote for a party are measured based on an open-ended question. We acknowledge that the reliability and validity of self-reported motivations via open-ended questions is debated within research as respondents could answer in a socially desirable manner or post-rationalize their choice (Geer, 1988; Murphy et al., 2020). Yet these biases tend to be more limited in exit poll data as respondents are interviewed right after they have voted. Nevertheless, to strengthen the quality of the measurements, we made sure that answering the open-ended questions was not obligatory as research stated that mostly respondents who are uninterested or unable to answer the question leave such questions unanswered (Geer, 1988). Second, we tested for the coherence of answers provided by respondents, comparing our coding with other answers (Lefevere, 2010; Van Holsteyn, 1994). Third – and most importantly – we do not rely only on exit poll data but, additionally, conducted interviews with Muslims to explain their electoral choices more in depth, expanding our understanding thereof. We gain insights into not only their electoral behaviour and motivations but also their decision-making process. We will elaborate on the interviews in the next section.

For this study, the open question in the survey about party voting motives has been coded to map voters’ party motives (You have just voted for the municipal elections. Could you explain with your own words why you have voted for this list?). Seventy-nine per cent of interviewees responded to the question. Every response was assigned to a maximum of one code; thus, the categories are mutually exclusive (see Table 2). We coded the motivations inductively, but most codes aligned very well with the basic categories of the Michigan model: party evaluation, candidate evaluation and issues. We recoded them accordingly but added a separate category for religiosity issues – to explore the distinctiveness of Muslims’ electoral behaviour – next to the category political alienation when respondents stated to have voted owing to the mandatory voting.

Because of the interest in religion, we coded motives mentioning a religious practice (i.e. religious slaughter, headscarf ban, mosque attendance) as religiosity issues. We hereby apply a strict interpretation of religious issues, possibly excluding themes such as anti-discrimination or education, which could also have religious connotations. A combination of party evaluation and multiple issues is coded as party evaluation. When someone feels close to a party, they will, logically, also value the party position concerning the issues. This is true of the combination of party evaluation and candidates as well: voters first vote for a party and subsequently cast a preferential vote(s) for candidate(s) within the party. Other multiple issues were coded as issues: for Muslims these concerned mostly anti-discrimination, social cohesion and exclusion in education and on the labour market. As for non-Muslims, most issues were related to poverty, mobility, climate and social cohesion. The first author coded the open question, and 125 responses were coded double by a second coder. To measure intercoder reliability, we calculated Cohen’s Kappa, which is 0.73 (S.E. = 0.55; N = 125). Table 2 gives an overview of codes and examples.

To understand whether Muslims cast a preferential vote owing to party evaluation, issues, religious issues, political alienation or candidates, we rely on the same coded motivations as explained previously, except that for candidates we also explore whether voters are more likely to vote preferential because they know a candidate or owing to the competences of candidates. In what follows, we will elaborate more on the variables used in our statistical analyses.Table 2 Coding scheme of self-reported motivations to vote for a partyCodes Examples of voting motives Religious Issues Motive For change concerning the feast of sacrifice and the ban on veils, Muslim tolerant Issues Motive Against poverty and to give chances to the unemployed, socio-economic policy Alienation Motive voting is compulsory, the least bad Party Evaluation Motive I share their values and vision, evaluation Candidate Motive I trust the candidate, I voted for my husband Source: Azabar & Thijssen (2020a).

4.1.1 Operationalization of Dependent, Independent and Mediating Variables

In this article, we aim to explore the underlying mechanisms of the relationship between self-reported Muslim identification and voting, on the one hand, leftist and, on the other hand, preferential through mediators using MPLUS. Mediators tell us something more about how an independent variable impacts the dependent variable. We acknowledge that in this case, with the use of reference categories, multiple models are possible. However, to maintain a clear overview, we only showcase the models with significant mediators, notably issues and party evaluation, as these models are complementary.

4.1.1.1 Dependent Variables

Left vote – With regard to our first dependent variable explaining the leftist party vote (left), we asked respondents which list they had voted for using the mock ballot tool. We constructed two variables for the left vote, pointing at, respectively, voting for the traditional leftist parties labelled left vote (the Radical Left, the Greens and the Social Democrats) and one where the Christian Democrats, as a centre party, are included (Leftcdv). We will run the mediation analyses with both DVs. Pref vote – With regard to our second dependent variable explaining whether respondents have cast a preferential vote or not (Prefvote), we coded respondents who cast a list vote as 0 and those who cast a preferential vote as 1.

4.1.1.2 Mediating Variables

For the mediating variables explaining the relationship between the dependent and the independent variables, we posed the following question: You have just voted for the municipal elections. Could you explain in your own words why you have voted for this list? We then coded respondents’ self-reported motives mentioned in Table 2 (Party evaluation, Candidate, Religious issues, Issues and Alienation). When applicable, we coded 1, otherwise 0. See Table 3 for an overview of registered motives. We will use the same motivations to explain the dependent variable Prefvote. In addition, to further explore Muslims’ preferential voting, we questioned respondents in the exit poll why they voted for a candidate offering them three options, notably (a) because of their personality/charisma (b) because of their competences and (c) because they know them. We then created dummy variables to explore whether these could mediate between Muslim identification and casting a preferential vote (KnowCandidate, Personality, Competence).

Table 3 Self-reported motivations to vote for a party according to Muslims/non-MuslimsCodes: motivations to vote for party Muslims

(N = 343)Non-Muslims

(N = 3236)Religious Motive 6.4 % 0.5 % Issues Motive 14.2 % 13.4 % Alienation Motive 11.7 % 11.6 % Party evaluation Motive 48.8 % 55.4 % Candidate Motive 18.9 % 19.1 % 100 % 100 % Source: Azabar & Thijssen (2020a).

4.1.1.3 Independent Variables

For the independent variable Muslim, we questioned respondents as follows: Would you consider yourself affiliated to any specific philosophical denomination or religion? If yes, which one? Respondents who self-identified as Muslim were coded 1; all others as non-Muslim. As we acknowledge the heterogeneity of the latter category, we also compare Muslims with only Catholic/Christian respondents as a robustness check. Next, with regard to the independent variable Migrant, we asked voters about their nationality as well as their parents’ nationality. When respondents or at least one of their parents lacked a nationality of a European country, we coded 1, while all others were coded 0. We further control for socio-demographic variables such as Gender (male = 0; female = 1), Agedum (18-34, 35+), Edudum (low = 0, high = 1) and Region (Brussels/Wallonia = 0, Flanders = 1).

4.2 In-depth Interviews

The seventeen in-depth interviews are part of a broader project on Muslims’ political participation in Belgium. Questioning their electoral participation, motives and decision-making process, but also their challenges and obstacles in the political arena, we aim to shed light on Muslims’ electoral and non-electoral participation, next to their decision-making process. Respondents were queried about their personal political biographies, notably how they describe and evaluate current politics, the issues that concern them and engagements herein, the range of political actions they have participated in and their motivations to do so. Lastly, we queried them about the role of religion in their participation. Participants contacted the first author, consenting to an interview after they had seen the call distributed by civil society organizations or being asked by someone in their network as we applied snowball sampling. As most interviewees were mostly higher educated and politically interested, we used purposive sampling to interview lower educated Muslims. Participants who have agreed to the interviews were mostly second- or third-generation Muslims with a Moroccan background, two with a Turkish background and two converts with an ethnic majority background.5x When either both or one of the parents/grandparents are born in a non-EU country, we refer to the participants as, respectively, second and third generations. Nine defined themselves as women, seven as men and one as non-binary. The majority, twelve participants, are studying or have finished their higher education, whereas five participants had obtained (only) their secondary degree.

The interviews were conducted in February-April 2021 and took on average 1 hour 45 minutes. Owing to Covid-19 measures, half of the interviews were conducted in person with respect for all the applicable measures, while the other half took place online using Skype or ZOOM. The names of the participants were altered in order to preserve confidentiality. All interviews were conducted by the first author, who is Muslim and recognizable as such, which could generate a sense of familiarity and openness towards Muslim participants, particularly those who feel otherised. The interviews were transcribed and analysed with NVivo. For this study, we coded the interview data deductively according to the themes of interest, notably, on the one hand, party choice and, on the other hand, candidate choice, together with the motivations hereof. We also took note of the considerations Muslims made while casting a vote. -

5 Findings

5.1 Quantitative Section: What Explains the Leftist and Preferential Vote of Muslims Vis-à-vis Non-Muslims?

Because the five motivational categories were measured in a disjointed and exhaustive way, in order to avoid collinearity problems, we test the complete set of mediations in two models, notably Model 1A and Model 1B. Both models have a good fit with a chi-square = 67.39 (df = 18, p = 0.00), RMSEA = 0.03 (Model 1A) and chi-square = 46.46 (df = 17, p = 0.00), RMSEA = 0.02 (Model 1B). We present the models with significant regression coefficients (p < 0.05) only. As we compare Muslims with the heterogeneous group of non-Muslims, we conduct robustness checks for all analyses comparing Muslims with the Catholic/Christian voters (see Appendixes 1 and 2). All in all, our analyses show similar findings, notably the role of issues and party evaluation on Muslims’ leftist party vote.

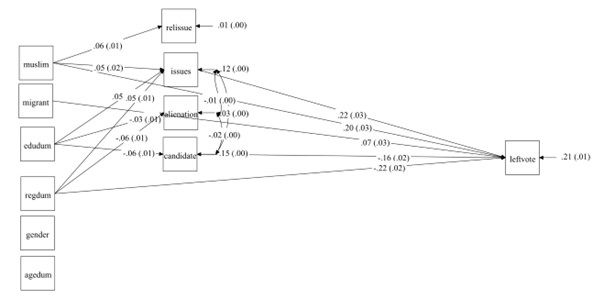

Mediation analysis explaining Muslims’ leftist vote (Path Model 1A) Mediation analysis explaining Muslims’ leftist vote (Path model 1B)

Mediation analysis explaining Muslims’ leftist vote (Path model 1B)

Figure 1A confirms H2a as the effect of Muslim on the left vote is significantly mediated by their inclination to vote in terms of issues compared with the reference category party evaluation. Muslims are significantly more issue voters vis-à-vis non-Muslims, and issue voters, in turn, tend to vote for a party of the left. In other words, the fact that Muslims more often cast a left vote, compared with non-Muslims, can partly be explained by their issue preferences (B = 0.01, S.E. = 0.00, p = 0.00). Figure 1B tells a complementary story. H1a can be falsified because the leftist Muslim vote is significantly mediated by the fact that they are less driven by party evaluation. One can therefore also say that the leftist Muslim vote is partially driven by the fact that left voters are less motivated by party evaluation. Yet we should point out that the size of both mediation effects is relatively small. This is reflected in the robust direct effect of being Muslim in model 1A (B = 0.20, S.E. = 0.03, p = 0.00) and Model 1B (B = 0.20, S.E. = 0.03, p = 0.00). Apparently, only a relatively small part of the leftist Muslim vote can be explained by their specific motives, which points at a strong structural basis, such as the fact that they tend to belong to less affluent minority groups. Interestingly, the direct effect of being Muslim is stronger than the direct effect of having a migration background (B = 0.07, S.E. = 0.03, p = 0.00) on the dependent variable left vote, which can partly be explained by their particular issue preferences. Furthermore, candidates (H3a) and religious issues (H5a) do not significantly mediate the left vote vis-à-vis non-Muslims, and hence we reject both hypotheses. Lastly, as we hypothesized political alienation (H4a) to not explain Muslims’ leftist preference, we confirm H4a. These results are confirmed by our robustness test comparing Muslims with Catholic/Christian voters (see Appendix 1). As expected, the Muslim vote is more often driven by religious issues, compared with that of non-Muslims. Yet these religious issues do not lead to more votes for the left in Model 1A. However, Model 1B shows that religious issues attenuate left voting when comparing Muslims with the heterogeneous group of non-Muslims. A robustness test comparing Muslims with Catholic/Christian voters shows that this effect is non-significant and thus disappears (see Appendix 1). Our main findings, notably issues and party evaluation mediating Muslims’ leftist party vote, remain intact.

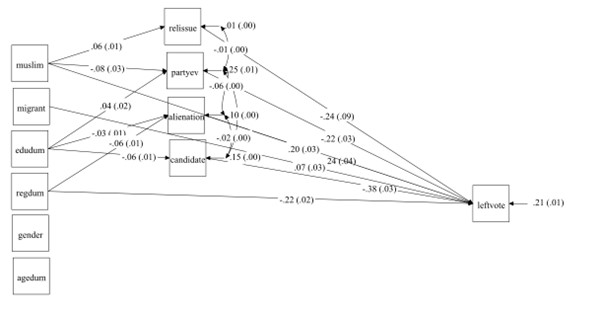

In Figures 2A and 2B we explore the specific motivations Muslims might have to cast significantly more preference votes vis-à-vis non-Muslims (Azabar et al., 2020b). As voters according to the Belgian electoral system first choose their preferred party and subsequently cast a list or preferential vote (André et al., 2017), in Figures 2A en 2B we also account for the mediator left vote when explaining Muslims’ likelihood of voting preferential. Figures 2A en 2B show the results for the dependent variable cast a preferential vote (no/yes) and mediating variables of the Michigan model and Muslim-specific variables, notably party evaluation (H1b), issues (H2b), candidates (H3b), KnowCan (H3c), Competences (H3d), political alienation (H4b) and religious issues (H5b). Both models have a good fit with a chi-square = 107.95 (df = 30, p = 0.00), RMSEA = 0.02 (Model 2A) and chi-square = 316.1 (df = 30, p = 0.00), RMSEA = 0.05 (Model 2B). Given the limited number of specific factors with regard to preferential voting, these results should be interpreted with caution.Mediation analysis explaining Muslims’ preferential vote (Path model 2A) Mediation analysis explaining Muslims’ preferential vote (Path model 2B)

Mediation analysis explaining Muslims’ preferential vote (Path model 2B)

Model 2A and 2B indeed show that Muslims are more inclined to cast a preference vote in local elections compared with non-Muslims (B = 0.06; S.E. = 0.02; p = 0.02) and, second, those with a migration background more than those without a migration background (B = 0.06; S.E. = 0.03; p = 0.02). However, this effect is not significantly mediated by the Michigan model variables, notably party evaluation (H1b), issues (H2b) and candidates (H3b). We therefore confirm H1b, as party evaluation does not play a significant role in the likelihood of casting a preferential vote for Muslims, and rejecting H2b and H3b. As for explaining casting a preferential vote, our models show that women, the higher educated and Flemish voters cast more preferential votes than, respectively, men, lower educated and voters in Wallonia and Brussels, as previous studies claimed (Wauters et al., 2020). When focusing on the questioned motivations to cast a preferential vote (Knowing a Candidate, Competences or Personality), we can deduce the following: knowing a candidate personally generally leads to a higher likelihood of voting preferential compared with voting for a candidate owing to their personality (B = 0.18; S.E. = 0.07; p = 0.02). In addition, voting for a candidate because of their competence appears to be less likely to explain casting a preferential vote compared with the personality of the candidate (B = -0.20; S.E. = 0.05; p = 0.02). However, none of these motivations significantly explain Muslims’ likelihood of voting preferential vis-à-vis non-Muslims, thus falsifying H3c and H3d. Interestingly, there are no significant indirect effects concerning the Muslim-specific variables political alienation, thus confirming H4b while rejecting H5b as religious issues do not explain Muslims’ preferential voting. Our robustness test vis-à-vis Catholic/Christian voters shows similar results (Appendix 2). In the next section, we aim to (further) explore Muslims’ motivation to vote (a) for a leftist party and (b) to cast a preferential vote as our last analyses reveal less on the motivations to cast a preference vote.

5.2 Qualitative Section: What Explains the Leftist and Preferential Vote of Muslims?

As earlier research revealed, Muslim voters are more likely to vote for leftist parties (Cesari, 2014; Zibouh, 2013), preferential and for Muslim candidates (Azabar et al., 2020b; Heath et al., 2015). In this section, we further disentangle these electoral preferences6 by focusing on their decision-making process.

5.2.1 It’s All about the Issues!

When Muslim respondents were queried about their party vote, all but two respondents answered that they had voted for a left-wing party (notably Radical Left, Greens or Social Democrats), pointing to earlier research on Muslims’ leftist party preferences. The other two respondents had either voted for a right-wing party or blank.

But how can we explain these leftist party preferences? And what considerations do Muslims have concerning their party vote? A few respondents stated that they always vote for the same party at local elections referring to party evaluation. The radical vision of changing the society to be more just spoke to Kamal (35 years, unemployed) as he stated: ‘Since 2012, I consistently vote for the radical left’, while Yasmina (41 years, housewife) talked about how she shares the same ideas as the party she voted for and thus feels ‘connected’. Interestingly, Karim (47 years, city official) mentioned that he ‘principally vote[s] for the Christian Democrats’ because of their Christian background, reminding him of his own religion. However, a councillor with a Turkish background (Social Democrats) stood out to him because of his accomplishments at the local level, which made Karim (47 years) vote for the Social Democrats at the 2018 local elections. Interestingly, even these respondents shared that although at the local elections they vote in line with their party evaluation, they sometimes make other choices depending on the level of elections. For instance (Kamal, 35 years) stated to vote for the Greens on the national and European level as they can do more than the radical left party PVDA, because the latter is a small party.

Furthermore, more than half of the respondents refer to issues such as socio-economic issues and the welfare system but also anti-racism, anti-discrimination and respect for human rights while stressing the need for a more just society. These topics were earlier suggested by Zibouh (2013) and Cesari (2014) as salient issues owing to the sociopolitical position of Muslims influencing their party vote. Issues such as the climate and Palestine were also mentioned, albeit to a lesser extent. Some respondents, mostly higher educated, have taken the time to immerse themselves into the party positions (and accomplishments) on certain matters on inequality, or issue publics (Popkin, 1991), while others formed an opinion through discussions, short campaign ads and following politicians on Facebook. All respondents addressed to discuss their party preferences with family and (close) friends, or were even asked for advice by family members and friends, with the exception of Muhammed (34 years, security agent). As he voted for the nationalist party N-VA, he stressed that it’s impossible to discuss his vote with Muslims because they would exclude and perceive him as ‘a traitor’ for having voted for a right-wing party.

Thirdly, almost all spoke about voting for what is better for minorities as a group. Indeed, aiming to explain the voting preferences of voters with a non-western background in Norway, Bergh and Bjorklund (2011) found the strongest support for the group voting thesis claiming that one’s ethnic background trumps other concerns when voting. The same goes for our mediation analysis in this article as a strong effect remains of being Muslim on the independent variable Left vote. Most respondents also stated that they voted with (full) conviction for a party taking a more radical stance against injustices affecting, primarily, minorities. Interestingly, for some their voting behaviour is conditioned by the chance that the party could govern as two respondents refrained from voting for the radical left party PVDA despite supporting their ideas, because they are ‘a small political party with a few seats … the chance that something could come out of that …’ (Linda, 31 years, nurse). Second, earlier negative experiences with parties explain why some refrain from voting for a traditional party, although they did before. One example that was often brought up was the Social Democratic party owing to the implementation of a headscarf ban for clerks in Antwerp, the biggest city of Belgium.6x In 2007, Patrick Janssens, Social Democratic party, became mayor of Antwerp. One of the first policy measures he implemented was a dress code for clerks, which included a ban on veils. This sparked a debate on the neutrality of civil servants and the role of religion, questioning to what extent wearing a headscarf violates the neutrality of the state. This is illustrated by Hakim (29 years, IT consultant), explaining his party vote as follows:Hakim: I have earlier voted for the Social Democrats, then for the Greens. At the recent local elections, I have voted for the radical left. The first time I voted, I was influenced by my friends and family claiming that the Social Democrats are the best party for our community. Much has happened [in] the last ten years, especially with the ban on veils. I now follow some politicians of the radical left party on social media. [own emphasis]

Interviewer: What has attracted you to the radical left party?

Hakim: Especially their discourse against racism. They have never had the chance to govern contrary to the Social Democrats. The Greens also have had the opportunity. … We need people who dare to speak.

Clearly, an increasing popularity of the radical left party among Muslim respondents is present. A recent study of Azabar & Thijssen (2020a) in Belgium noticed how the radical left party PVDA gained support from Muslims compared with the local elections of 2012. In the same vein Ezrow (2008) has found that niche parties do better electorally when they promote radical (policy) stances. Or, as Moussa (40 years, unemployed) stated, ‘The radical left party is a middle finger to the radical right party. That’s why I decided to vote for the radical left party’.

5.2.2 The Muslim Vote: ‘Who Else Can Represent Me?’

Describing their ideal candidates, most respondents stressed willingness to listen to voters, presence among the people and complete transparency about what one can achieve as important assets, pointing to the preference of delegates as representatives. Safa (42 years, researcher) noted, ‘Someone who can be among people, can listen and at the same time knows how to play the game. Those are politicians who I respect.’ Muhammed (37 years, security agent) emphasized that politicians should decide on policy matters in the interest of the voters (trustee). Concerning socio-demographic characteristics, some preferred Muslim candidates when available on the list, while others stressed that candidates do not have to belong to a minority group to represent them but emphasized the importance of an open mind set and eagerness to learn.

When respondents elaborated on their actual preferential vote(s), a majority of the interviewees revealed that they had voted for Muslim candidates. Earlier research indeed found that Muslims are more likely to vote for Muslim candidates in urban cities with a Muslim electorate (Azabar et al. 2020b; Heath et al., 2015). A few also referred to well-known candidates such as the first candidate on the list. But why? Are Muslim respondents more prone to vote for Muslim candidates to endorse candidates who look like them (descriptive representation), to support ‘one of our own’ (symbolic representation), or do they expect a policy that will benefit them (substantive representation)?

A few interviewees said they highly value minority candidates as they seem to have overcome barriers such as discrimination and exclusion. For instance, these candidates get the attention of Ayse (24 years, student), who ‘knows how hard it is for minorities to move up in the society’. So, they have my respect’. Although less, voting for someone of us to support them occurs (symbolic representation). Wissam (37 years, teacher) also emphasized how she identifies with candidates who look like her, uttering: ‘I am a woman of color with a headscarf. You always mirror yourself, so I am delighted when I see that a woman has made it’, referring to the importance of descriptive representation. But most of the time, Muslims believe that Muslim candidates will benefit them. For instance, Louiza (34 years, housekeeper) noted, ‘Maybe, it’s a bit discriminatory, but I do prefer minority names on the list. They have my vote, because I know it will be in my favor.’ She went on to express her belief that Muslim candidates would not harm other minorities owing to the shared experiences.

However, a majority of the respondents who voted for Muslim candidates were also critical while expressing their sympathy for Muslim candidates. Some referred to the use of Muslims merely to diversify the party lists or the particracy pointing to the power of political parties in the Belgian system. Ayse (24 years, student) noted that in a particracy ‘the people we prefer [Muslims], have less to say within their parties which is disappointing’. Respondents therefore stated that their support was conditioned not only by minoritized candidates but also by their narratives and actions. In the same vein, Moussa (40 years, unemployed) said he wanted ‘a real Muslim’ as a representative who does not discard their Muslimness. This combination of being Muslim and having the right narrative and actions to defend minorities’ interests helps Muslims to feel represented in politics. Karim (47 years, city official) provided the following explanation:[I feel represented] when someone from my own group is part of the politics, but it’s not simple. I always give the example of the Turkish councilor in my city. He was affiliated with the Social Democrats and part of the former local government. He really realised a lot. But then he disappeared, and all his work disappeared with him. … I actually have more faith in him than the party. Now there is a new councilor, a new policy, a new idea.

When Karim (47 years, city official) elaborated on voting for someone of ‘his own group’, firmly adding, ‘Who else can represent me?’, one can ask themselves what he meant by someone of ‘his own group’. Interestingly, Karim (47 years) has a Moroccan migration background and expatiated on a politician with a Turkish background as someone of ‘his own group’, suggesting that the Muslim identity trumps ethnicity when voting for candidates (see also Azabar et al., 2020b). Accordingly, other respondents gave examples of candidates they felt represented them, sharing a Muslim background but differing in migration background. The same goes for Christine (24 years, student), a convert, who voted for a Muslim with a migration background as she felt he would fight against inequalities experienced by Muslims. Indeed, previous studies have claimed the importance of religion as an identity marker, in particular, when Islam has been fiercely debated in the public sphere (Dancygier, 2014; Fadil et al., 2015; Voas & Fleischmann, 2012). Subsequently, these findings show how Muslim voters perceive each other as members of the in-group (Muslims) when casting a vote for candidates.

A few of the respondents stated that it did not matter whether candidates were Muslim or had a migration background, as long as they had principles and were eager to defend the interests of the marginalized and excluded. Marwan (37 years, educational worker) spoke about how he earlier voted solely for Muslim candidates but was disappointed as these candidates followed their party line on some issues although he expected otherwise. Therefore, it is people who ‘stand up for principles and for Muslims’ who deserve his vote. In the same vein, Yasmina (40 years, housewife) stated that she was not guided by gender or religion of candidates but that ‘the message of candidates is more important’. Muslims’ disadvantaged position and earlier experiences seem to push voters to inform themselves about the policies and stances of (Muslim) candidates. -

6 Conclusion and Discussion

Previous studies have found evidence of Muslims voting primarily leftist and preferential; however, explanations remained unclear. This article addresses this issue and contributes to the literature on minorities’ political participation and integration through the exploration of Muslims’ electoral choices and underlying motivations. Drawing on exit poll and mock ballot data of the local elections of 2018 and seventeen in-depth interviews with Muslims elaborating on their motivations and decision-making process when voting, we came to the following conclusions.

The leftist party preference of Muslims vis-à-vis non-Muslims is driven by their stronger preoccupation with particular issues and their more limited party evaluation motives. In the interviews, the issues mentioned were related primarily to their precarious socio-economic situation but also addressed their marginalized position caused by discrimination and negative stereotypes in society. Indeed, scholars have suggested that the electoral choices of Muslims could be influenced by motives related to socio-economic issues and equality issues to the detriment of party evaluation (Cesari, 2014; Zibouh, 2013). Our study empirically confirms these assumptions. Moreover, other motivations such as candidates, political alienation or religious issues do not seem to explain the leftist party vote of Muslims. Interestingly, the direct effect of Muslim identification on the left vote is robust and significant, showing that being Muslim relates to voting leftist despite the presence of the mediators and control variables in the model. In addition, the Muslim effect is stronger than the migrant effect, pointing to the salience of Muslim as an identity marker, also in the political arena, as claimed by scholars earlier (Azabar et al., 2020b; Dancygier, 2017).

Second, with regard to preferential voting, we find that Muslims indeed vote more preferential than do non-Muslims, a trend that points to how marginalized positions could provoke a specific type of political behaviour, as André et al. (2017) suggested. Contrary to what we hypothesized, neither the Michigan variables nor the Muslim-specific variables explain the likelihood of preferential voting. But whom do they choose to represent them – and why? Our qualitative findings point to Muslims stating that socio-demographics of candidates do not matter when discussing the prerequisites of ideal candidates. However, when asking about their actual candidate choices, almost all voted for Muslims to strengthen the descriptive and symbolic representation, but primarily for substantive reasons. Our findings show that Muslim respondents expect that Muslim candidates will defend their interests, although this idea is nuanced owing to the particracy: parties still have the power, not the candidates. These qualitative findings resonate with earlier studies on the Muslim vote (Azabar et al., 2020b; Heath et al., 2015).

In this study we have relied on self-reported motivations of party vote using open-ended questions, although this approach is often criticized because it allegedly leads to post hoc rationalization and socially desirable answers (Rahn et al., 1994). Yet this is less problematic in exit polls owing to the more limited recall biases. Moreover, we took some precautions, i.e. questions were not obligatory to answer and tested the coherence of the answers. More importantly, not only relying on exit poll data, our interviews further elaborate on Muslims’ electoral choices, their considerations and motivations, shedding light on voting leftist (which leftist party and why) and, secondly, to vote preferential (which candidates and why). Nevertheless, our findings could be tested with more objective measures, when the situation permits it, considering that participation of Muslim minorities in survey research is complicated.

Overall, our study shows the importance of examining Muslims’ electoral behaviour in non-Muslim majority societies as these findings show that, in line with the recent findings of Goerres et al. (2021), Muslims’ leftist vote can be explained by the central factors in the Michigan model and not by religious issues. However, the same variables do not explain Muslims’ tendency to vote preferential. This study shows that the strong direct effects of Muslim identification on left and preferential voting still leave much to discover about Muslims’ political behaviour, in particular, Muslims’ likelihood of voting preferential. Our qualitative findings point to expectations concerning representation explaining the preference for Muslim candidates. More empirical studies unravelling the preferential vote beyond candidate choices could therefore be fruitful. Second, it would be interesting to research possible differences within the Muslim group (i.e. due to gender or different migration backgrounds), applying a more intersectional approach. To what extent are these differences among Muslims meaningful when casting a vote?

As the social and political position of Muslims in the West is comparable owing to a shared labour migration narrative and scrutiny that Muslims experience, we believe our findings can be extrapolated to other West European countries, meaning issues drive Muslims’ electoral behaviour. Yet more research in other countries could strengthen our claim. What we do know for certain is that the stereotype of the politically disintegrated Muslim does not hold water. References Amjahad, A. & Sandri, G. (2012). The Voting Behaviour of Muslim Citizens in Belgium. Presented at the IPSA World Congress. Madrid, 8-12 July. Retrieved from www.academia.edu/3521138/The_Voting_Behaviour_of_Muslim_Citizens_in_Belgium.

Amnesty International. (2012). Europe. Choice and Prejudice: Discrimination Against Muslims in Europe. Retrieved from www.amnesty.org/en/documents/EUR/01/001/2012/en/.

André, A., Wauters, B. & Pilet, J.-B. (2012). It’s Not Only About Lists: Explaining Preference Voting in Belgium. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 22(3), 293-313. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2012.692374.

André, A., Depauw, S., Shugart, M. S. & Chytilek, R. (2017). Party Nomination Strategies in Flexible-List Systems: Do Preference Votes Matter? Party Politics, 23, 589-600.

Azabar, S. & Thijssen, P. (2020a). De regionale verschillen in het stemgedrag en stemmotieven van moslims nader bekeken. In R. Dandoy, J. Dodeigne, K. Steyvers & T. Verthé (Eds.), Lokale kiezers hebben hun voorkeur. De gemeenteraadsverkiezingen van 2018 geanalyseerd, 87-107. Vanden Broele.

Azabar, S., Thijssen, P. & Van Erkel, P. (2020b). Is there such a thing as a Muslim vote? Electoral Studies, 66,1-23. doi: 10.1016/J.ELECTSTUD.2020.102164

Azabar, S. & Thijssen, P. (2021). The electoral agency of Muslimahs: an intersectional perspective on preferential voting behavior. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1-23. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2021.1902793

Bayrakli, E. & Hafez, F. (2019). European Islamophobia Report 2019. Retrieved from www.islamophobiaeurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/EIR_2019.pdf.

Berger, P. (1999). The Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religion and World Politics (1st ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

Bergh, J. & Bjorklund, T. (2011). The Revival of Group Voting: Explaining the Voting Preferences of Immigrants in Norway. Political Studies, 59(2), 308-327. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00863.x.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E. & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American Voter (1st ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Castano, S. (2014). The Political Influence of Islam in Belgium. The Open Journal of Sociopolitical Studies, 7(1), 133-151. doi: 10.1285/i20356609v7i1p133.

Cesari, J. (2014). Political Participation Among Muslims in Europe and the United States. In K. H. Karim & M. Eid (Eds.), Engaging the Other, 173-190. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Curtice, J., Fisher, S. D., Ford, R. & English, P. (2018). An analysis of the results. In P. Cowley & D. Kavanaugh (Eds.), The British General Election of 2017, 449-495. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cutler, F. (2002). The Simplest Shortcut of All: Sociodemographic Characteristics and Electoral Choice. Journal of Politics, 64, 466-490.

Dalton, Russell J. (2014) Citizen politics: public opinion and political parties in advanced industrial democracies. London: Sage.

Dancygier, R. (2014). Electoral Rules or Electoral Leverage? Explaining Muslim Representation in England. World Politics, 66(2), 229-263. doi: 10.1017/S0043887114000021.

Dancygier, R. (2017). Dilemmas of Inclusion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dargent, C. (2009). Musulmans Versus Catholiques: Un Nouveau Clivage Culturel et Politique ? Congrès International des Associations Francophone de Science Politique. Retrieved from www.congresafsp2009.fr/sectionsthematiques/st42/st42dargent.pdf.

Elshayal, K. (2018). Muslim Identity Politics: Islam, Activism and Equality in Britain (1st ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing.

European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia. (2006). Muslims in the European Union: Discrimination and Islamophobia. Retrieved from https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2012/muslims-european-union-discrimination-and-islamophobia

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2017). EU MIDI II: Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey Muslims. Retrieved from http://www.marinacastellaneta.it/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/fra-2017-eu-minorities-survey-muslims-selected-findings_en.pdf

Ezrow, L. (2008). On the inverse relationship between votes and proximity for niche parties. European Journal of Political Research, 47(2), 206-220. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2007.00724.x.

Fadil, N., El Asri, F. & Bracke, S. (2015). Islam in Belgium: Mapping An Emerging Interdisciplinary Field of Study. In J. Cesari (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of European Islam, 222-255. Oxford University Press.

Fleischmann, F., Phalet, K. & Klein, O. (2011). Religious Identification and Politicization in the Face of Discrimination: Support for Political Islam and Political Action Among the Turkish and Moroccan Second Generation in Europe. British Journal of Social Psychology, 50, 628-648. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02072.x.

Fleischmann, F., Phalet, K. & Klein, O. (2012). Gepolitiseerde Moslimidentiteit. Retrieved from https://soc.kuleuven.be/ceso/ispo/downloads/ISPO%202009-11%20Ongelijke%20kansen%20en%20ervaren%20discriminatie.pdf.

Fleischmann, F. & Phalet, K. (2012). Integration and religiosity among the Turkish second generation in Europe: A comparative analysis across four capital cities. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35(2), 320-341.

Goerres, A., Mayer, S. J. & Spiers, D. C. (2021). A New Electorate? Explaining the Party Preferences of Immigrant-Origin Voters at the Bundestag 2017 Election. British Journal of Political Science 52(3), 1032-1054. doi: 10.1017/s0007123421000302.

Geer, J.G. (1988). What do open-ended questions measure? The Public Opinion Quarterly, 52(3), 365-371. doi: 10.1086/269113.

Górecki, M. & Marsh, M. (2014). A Decline of ‘Friends and Neighbours Voting’ in Ireland? Local Candidate Effects in the 2011 Irish ‘Earthquake Election’. Political Geography, 41, 11-20. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.03.003.

Habermas, J. (2008). Notes on Post-Secular Society. New Perspectives Quarterly, 25(4), 18-29. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5842.2008.01017.x.

Heath, O., Verniers, G. & Kumar, S. (2015). Do Muslim Candidates Prefer Muslim Candidates? Co-religiosity and Voting Behaviour in India. Electoral Studies, 38, 10-18. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2015.01.005.

Helbling, M. & Traunmüller, R. (2020). What is Islamophobia? Disentangling Citizens’ feelings toward ethnicity, religion and religiosity using a survey experiment. British Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 811–828. doi:10.1017/S0007123418000054.

Hirschman, A.O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty. Decline in firms, organizations and states. Harvard University Press.

Inglehart, R. (1977). Values, Objective Needs, and Subjective Satisfaction Among Western Publics. Comparative Political Studies, 9(4), 429-458. doi: 10.1177/001041407700900403.

Jacobs, D., Phalet, K. & Swyngedouw, M. (2004). Associational Membership and Political Involvement Among Ethnic Minority Groups Brussels. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30, 543-559. doi: 10.1080/13691830410001682089.

Lefevere, J. (2010). Verandering en stabiliteit van beslissingsregels tijdens de campagne van 2009. In K. Deschouwer, P. Delwit, M. Hooghe & S. Walgraeve, (Eds.). De stemmen van het volk (pp. 51-74). Brussel: VUB press.

Mansbridge, J. (1999). Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent “Yes”. Journal of Politics, 61, 628-657. doi: 10.2307/2647821.

Miller, A., Gurin, P. & Malanchuk, O. (1981). Group Consciousness and Political Participation. American Journal of Political Science, 25(3), 494-511. doi: 10.2307/2110816.

Modood, T. (2003). Muslims and the Politics of Difference. Political Quarterly, 74(1), 100-115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-923X.2003.00584.x.

Murphy, G., Loftus, E., Grady, R. H., Levine, L. J. & Greene, C. M. (2020). Misremembering Motives: The Unreliability of Voters’ Memories of the Reasons for Their Vote. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9(4), 564-575. doi: 10.1016/j.jarmac.2020.08.004.

Noppe, J., Vanweddingen, M., Doyen, G., Stuyck, K., Feys, Y. & Buysschaert, P. (2018). Vlaamse Migratie- En Integratiemonitor 2018. Agentschap Binnenlands Bestuur.

Open Society Foundation. (2011). Les Musulmans en Europe. Retrieved from www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/h-muslims-in-europe-french-20110912_0.pdf.

Peace, T. (2015). European Social Movements and Muslim Activism. Another World but with Whom? (1st ed.). Palgrave McMillian.

Pew Research Center. (2017a). Europe’s Growing Muslim Population. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/11/29/europes-growing-muslim-population/

Pew Research Center (2017b). Political and Social Views. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/07/26/political-and-social-views/

Peucker, M. (2016). Muslim Citizenship in Liberal Democracies. Springer International Publishing.

Popkin, S. L. (1991). The Reasoning Voter. University of Chicago Press.

Rahn, W.M., Krosnick, J.A. & Breuning, M. (1994). Rationalization and derivation Processes in Survey Studies of Political Candidate Evaluation. American Journal of Political Science 38(3), 582-600. doi: 10.2307/2111598

Rosema, M. (2006). Partisanship, candidate evaluations and prospective voting. Electoral Studies, 25(3), 467-488. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2005.06.017.

Sanders, D., Heath, A., Fisher, S. & Sobolewska, M. (2014). The Calculus of Ethnic Minority Voting in Britain. Political Studies, 62(2), 230-251. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12040.

Sandri, G. & De Decker, N. (2008). Les Vote des Musulmans. In P. Delwit & E. Van Haute (Eds.), Les vote des Belges, Le comportement electoral des Bruxellois et des Wallons aux élections du 10 juin 2007. Université Libre de Bruxelles.

Sinno, A. (2012). The Politics of Western Muslims. Indiana University.

Sobolewska, M. (2014). Party Strategies and the Descriptive Representation of Ethnic Minorities: The 2010 British General Election. West-European Politics, 36(2), 615-633. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2013.773729.

Swyngedouw, M., Fleichman, F., Phalet, K. & Baysu, G. (2010). Politieke Participatie van Turkse en Marokkaanse Belgen in Antwerpen en Brussel. Retrieved from https://limo.libis.be/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=LIRIAS1792058&context=L&vid=Lirias&search_scope=Lirias&tab=default_tab&fromSitemap=1.

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. (1979). An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Brooks Cole Publishing.

Taush, A. (2019). Muslim Integration or Alienation in Non-Muslim-Majority Countries: The Evidence from International Comparative Data. Jewish Political Studies Review, 30(3/4), 55-99.

Teney, C., Jacobs, D., Rea, A. & Delwit, P. (2010). Voting Patterns Among Ethnic Minorities in Brussels (Belgium) During the 2006 Local Elections. Acta Politica, 45(3), 1-32. doi: 10.1057/ap.2009.25.

Togeby, L. (2008). The Political Representation of Ethnic Minorities: Denmark as a Deviant Case. Party Politics, 14(3), 325-343. doi: 10.1177/1354068807088125.

van der Eijk, C. & Niemöller, K. (1987). Electoral Alignments in the Netherlands. Electoral Studies, 6(l), 17-30.

Van Heelsum, A., Michon, L. & Tillie, J. (2016). New Voters, Different Votes? A Look at the Political Participation of Immigrants in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. In A. Bilodeau (Ed.), Just Ordinary Citizens, 29-45. University of Toronto Press.

Van Holsteyn, J.M. (1994). Het woord is aan de kiezer. Een beschouwing over verkiezingen en stemgedrag aan de hand van open vragen. Politiek Bestuurlijke Studieën. Leiden: DSWO Press

Verba, S., Schlozman, K.L. & Brady, H. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American Politics. Harvard university Press.

Verkuyten, M. & Yildiz, A. A. (2007). National (Dis)identification and Ethnic and Religious Identity: A Study Among Turkish-Dutch Muslims. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(10), 1448-1462. doi: 10.1177/0146167207304276.

Wauters, B. , Thijssen, P. & Van Erkel, P. (2020). Preference voting in the Low Countries. Politics of the Low Countries, 1, 77-106. doi: 10.5553/PLC/258999292020002001004

Voas, D. & Fleischmann, F. (2012). Islam Moves West: Religion Change in the First and Second Generations. Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 525-545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145455.

Zibouh, F. (2013). Muslim Political Participation in Belgium: An Exceptional Political Representation in Europe. In Nielsen, J. (Ed.), Muslim Political Participation in Europe, 17-33. Edinburgh University Press.

Appendices -

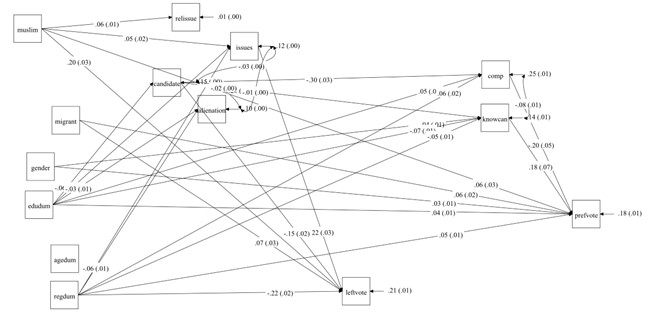

Appendix 1 Robustness test Model 1A-r and Model 1B-r – Muslims vis-à-vis Catholic/Christian respondents

Both models 1A-r en 1B-r have a good fit, with a chi-square = 29.28(df = 17, p = 0.03), RMSEA = 0.03 (Model 1A-r) and chi-square = 29.28(df = 17, p = 0.03), RMSEA = 0.02 (Model 1B-r). Similarly to our previous analyses, we reject H1a/H3a/H5a and confirm H2a/H4a, notably stating that issues and party evaluation mediate Muslims’ leftists vote vis-à-vis Catholic/Christian voters.

Model 1A robustness test – Muslims on left vote Model 1B robustness test – Muslims on left vote B (S.E.) B (S.E.) Total 0.34(0.03)*** 0.31(0.03)*** Total indirect 0.03 (0.01)* 0.02 (0.01)* Specific indirect Party evaluation Reference category 0.01 (0.00)* Religious issues 0.00 (0.01) -0.00 (0.01) Issues 0.02 (0.01)** Reference category Alienation 0.00 (0.00) -0.00 (0.00) Candidate 0.01 (0.00) * 0.02 (0.01)** *p < 0.0, **p < 0.01,***p < 0.001

-

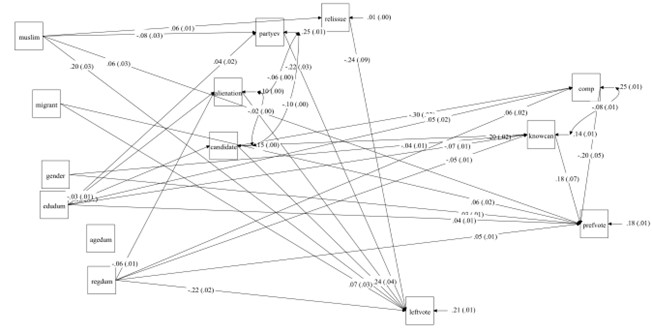

Appendix 2 Robustness test Model 2A-r and Model 2B-r – Muslims vis-à-vis Catholic/Christian respondents

Both models have a good fit, with a chi-square = 65.54 (df =30, p = 0.00), RMSEA = 0.02 (Model 2A-r) and chi-square = 46.41(df = 29, p = 0.02), RMSEA = 0.02 (Model 2B-r). Similar to our previous analyses, neither the Michigan model nor the Muslim-specific variables explain Muslims casting a preferential vote vis-à-vis Catholic/Christian voters.

Model 2A robustness test – Muslims on prefvote Model 2B robustness test – Muslims on prefvote B (S.E.) B (S.E.) Total 0.03(0.03) 0.03(0.03) Total indirect -0.03 (0.01)* -0.02(0.04) Specific indirect Party evaluation Reference category -0.00(0.00) Religious issues 0.00(0.00) 0.00(0.00) Issues -0.00(0.00) Reference category Alienation 0.00(0.00) 0.00(0.00) Candidate -0.00(0.00) -0.00(0.00) Competence of canndidate -0.00(0.00) 0.00(0.02) Know a candidate -0.01(0.01) -0.01(0.03) *p < 0.0, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Noten

-

1 In countries without compulsory voting.

-

2 Approximately 25% of Brussels inhabitants are Muslim (Zibouh, 2013).

-

3 43% of Muslims voting for Parti Socialist, 11% for the Greens, 19% for cdH and 15% for MR.

-

4 Antwerpen, Sint-Jans-Molenbeek, Sint-Joost-ten-Node, Charleroi and Luik.

-

5 When either both or one of the parents/grandparents are born in a non-EU country, we refer to the participants as, respectively, second and third generations.