Split Offer and Homogeneous Response in Belgium

-

1 Introduction

Since Schattschneider (1960) drew attention to the importance of the historic evolution of the nationalization of party politics in the US, the nationalization of political parties, party systems and electoral behaviour have received quite some attention in the political science literature (e.g.: Bochsler, 2010; Caramani, 2004; Chibber & Kollman, 2004; Jones & Mainwaring, 2003; Lago & Montero, 2009). Studies have suggested a wide variety of definitions and – especially – measurements that all, in one way or another, try to capture the degree to which the competition between parties and the electoral results produced by this competition are homogeneous across the whole territory of a country. All of these studies use indicators that measure either the nationalization of the party offer or the voter response or both of them. At times the nationalization of the party offer and the nationalization of voter response have been confused with each other, triggering a lively debate (Lago & Montero, 2009; Morgenstern & Potthoff, 2005). Confounding these two dimensions is, however, a comprehensible oversight, since the observed dynamics concern the same process: voters responding to the party offer. Obviously, voter response cannot be (or become) nationalized if the party offer is not national. Yet, as the recent debate on this topic has tried to highlight, these two dimensions are not identical, and this article intends to empirically illustrate this by looking at electoral politics in Belgium. By using the case of Belgium, we attempt to define more clearly what the concept of nationalization entails, what its limitations are, and how using different terms to identify different phenomena – nationalization of party offer and homogenization of voter response – would be more appropriate and improve our analytical understanding.

In the nationalization literature, Belgium is often cited as the typical example of a non- or denationalized country (e.g. Caramani, 2004), but no distinction is made between the two dimensions of nationalization. In this article we claim that Belgium can be considered a denationalized country when referring to one of the two dimensions of the nationalization concept (the party offer). With regard to the dimension of the nationalization of voting behaviour, however, it is improper to consider Belgium a country with low nationalization. The party offer in Belgium is quite peculiar, since there are no relevant state-wide parties (Deschouwer, 2012). All parties limit their activities to one of the two major (French or Dutch) language groups of the country and therefore also limit their electoral presence to the part of the territory where their potential voters live. So, while the party offer is clearly not nationalized, i.e. not homogeneous across the Belgian territory, this aspect is also the least interesting to investigate in this specific case. Yet voters might still respond in a very homogeneous way to each of the two separate party offers. In this article we therefore focus on the nationalization or, better, homogenization, of voter response.

By presenting and discussing the Belgian case, the article also wants to point out the methodological nationalism that is strongly present in this literature. Methodological nationalism refers to the almost automatic focus on the nation state as the unit of analysis in political science (Jeffery & Schakel, 2013; Jeffery & Wincott, 2010). For the study of the nationalization of politics this is quite obvious and explicit. The nationalization of electoral politics is an indicator of the degree to which the territorial boundaries of the state become meaningful and coincide with the boundaries of the political community in which political participation and representation is being structured (Flora, Kuhnle, & Urwin, 1999). It is part of the process of state formation, state consolidation and nation building. These processes are very important and have indeed shaped the way in which modern democratic politics function. And they have therefore also provided the usual lens through which actors, institutions and processes of democratic politics are being analysed.

As a consequence, a low degree of nationalization is believed to reflect an incomplete or unfinished state formation. Territorial homogeneity within the state is then a phenomenon that might remain under the radar for the very reason that methodological nationalism tends to hide it from view. Responding to Jeffery and Schakel’s plea for a ‘regional political science’ (2013, p. 300), we therefore analyse the territorial homogeneity of voter response in Belgium, which is often used as the typical example of a denationalized country (Caramani, 2004; Lago & Montero, 2009) and one of the countries in which territorial units within the national state boundaries have become increasingly important. We do so by taking not only the nation state but also the newly created territorial entities as a unit of analysis.

The article is further organized as follows. In the next paragraph we first discuss the concept of nationalization and the best possible ways to measure it. Next we present the case of Belgium, focusing on the interaction between party politics, voting behaviour and territorial organization. This is followed by the presentation of the empirical evidence on voter response to the party offer in Belgium as a whole, and for Flanders and Wallonia separately. We do find low nationalization at the Belgian state-wide level, but a high degree of homogeneity at the subnational level. -

2 Measuring Nationalization

In his seminal work on the nationalization of politics, Caramani (2004) found a general nationalization trend in Western European countries since the middle of the 19th century. In other words, he found that within almost all of the analysed countries the differences among subnational areas decrease as time goes by, and eventually disappear. National politics substitutes local politics (Caramani, 1996, 2004). By carrying out a comparative and longitudinal analysis, Caramani (2004) focuses mostly on the shift from territorial to functional cleavages. In this sense, Caramani’s (2004) argument finds its roots in the centre-periphery model proposed by Rokkan (1970), as the process of nationalization is connected with the state formation: ‘Processes of nationalization are in the first place dynamic evolutions and transformations of […] territorial structures’ (Caramani, 2004, p. 29). However, there is another important concept involved in this process, which is the process of politicization. This consists in ‘the breakdown of the traditional systems of local rule through the entry of nationally organized parties’ (Rokkan, 1970, p. 227).

Rokkan highlights the key role played by national mass parties in the nationalization process. This is a fairly intuitive element: a nationalized electoral offer allows for a nationalized electoral answer. As long as the parties were local, the voters could not ‘behave national’. This simple consideration leads us to the crucial point we want to make: even if the two concepts are obviously linked, it is imperative to make a distinction (and to understand the interplay) between the nationalization of the party offer and the answer given by voters, which is now defined as the nationalization of voter response. We wonder, however, if it makes any sense at all to try to determine the nationalization of voter response if the offer was not national to begin with. It is quite obvious that we are not dealing with the other face of nationalization, but with an answer to the degree of nationalization of the party offer. This is also evident in France, where electoral behaviour is more homogeneous in the Presidential elections (with the same candidates/parties for the whole county) than for the legislative elections (with different party combinations in different districts) (Russo, Dolez, & Laurent, 2013).

Making a clear distinction between the nationalization of the party offer and, as it is called now, the nationalization of electoral behaviour, is something that has been intensively discussed in the literature. As Lago and Montero (2009) point out, because of its intrinsically multidimensional nature, the concept of the nationalization of the party system has suffered from some ambiguity (Morgenstern & Potthoff, 2005). The main conceptual difference consists in either linking or completely separating the parties from voters’ support. Therefore, if Kasuya and Moenius (2008, p. 136) consider a party system nationalized when ‘the vote share of each party is similar across geographic units’, this does not apply to Caramani (2004), Jones and Mainwaring (2003) and Lago and Montero (2009), who claim that party system nationalization should refer solely to the party system structure. In order to provide a measure for the nationalization of the party system, Caramani (2004) and Lago and Montero (2009) propose their own indexes. Caramani (2004, p. 61) employs the territorial coverage, i.e. the percentage of territorial units of a country where a party presents a list. Lago and Montero (2009, p. 13) elaborate the local entrant measure (E1), an index that varies between 0 and 1 in which different weights are assigned according to two elements: the number of votes received by a party at the local level with respect to the total number of national valid votes, and the number of seats gained with respect to the total number of seats.

With regard to the so-called nationalization of the vote, there are numerous ways in which this can be conceptualized and, consequently, measured. Claggett, Flanigan, and Zingale (1984) propose a comprehensive classification that distinguishes three different dimensions of nationalization: 1) the homogeneity of the electoral support; 2) the source (or level) of political forces; 3) the type of answer. The first dimension is the one employed by the aforementioned research of Kasuya and Moenius (2008): we can say that an election is nationalized when the support for the parties is homogeneous across the units of a country. The second dimension refers to the tendency of the electorate to vote for national parties rather than local ones – this is a dynamic observed, for instance, in Italy (Caramani, 2006). The third dimension implies a dynamic element: the election is considered to be a stimulus, and the nationalization is operationalized as a uniform change between two elections.

Clearly, the first dimension refers to what happens within each single election, while the third one focuses on the movement between two elections; the second dimension can be operationalized in both ways, and Caramani (2004) highlights how Stokes (1965) and Katz (1973) used the third dimension as an indicator for the second. Morgenstern, Swindle, and Castagnola (2009) suggest a further classification in order to distinguish between the studies that focus on the static component of nationalization (Bochsler, 2010; Caramani, 2004; Lago & Montero, 2009; Russo et al., 2013) and those that focus on the dynamic element (Alemán & Kellam, 2008; Russo, 2014; Stokes, 1965, 1967).

Several measures have been constructed in order to measure these different dimensions of nationalization. With regard to the dynamic component, Morgenstern, Hecimovich, and Siavelis (2014) identify five main techniques: 1) the standard deviation at the district level (Butler & Stokes, 1969; Johnston, 1981; Kawato, 1987), 2) the coattails correlation of the different level of elections (Converse, 1969; Hoschka & Schunck, 1978), 3) the component-of-variance model (Bartels, 1998; Katz, 1973; Morgenstern & Potthoff, 2005; Stokes, 1965), 4) the Alemán and Kellam algorithm (2008) and 5) the multilevel model by Mustillo and Mustillo (2012).

Regarding the static component, there is an even larger variety of indexes available to measure it. Bochsler (2010) divides them into three main families:

indices of variance: variation of the parties’ territorial scores with respect to their national average (Lee, 1988; Rae, 1967; Rose & Urwin, 1975).

inflation measures: comparison of the number of parties at the local and national levels (Chibber & Kollman, 1998, 2004; Cox, 1999; Moenius & Kasuya, 2004).

distribution coefficient: measure proposed by Jones and Mainwaring (2003), basically the inverse of the Gini coefficient of inequality (Gini, 1921).

As the literature has highlighted, all these measures have serious limits. The first set of measures suffers from several problems: the lack of upper limits, not taking into account the size of the territorial units and their relative dimension (whether they are equally large), the scale invariance (small parties have smaller deviations than large parties) and the insensitivity of transfers (which is the result of the fact that the deviations are not weighted) (Bochsler, 2010; Firebaugh, 2003).

The second set of measures has proven to be unreliable since they may lead to incorrect interpretations. Finally, with regard to the distribution coefficient, Bochsler (2010) notes that because this index does not take into account the size and number of the territorial units, it might lead to biased estimates. However, he overcomes these difficulties by developing the standardized Party Nationalization Score (sPNS).

As mentioned before, all these indices measure the degree to which the electoral competition and voting behaviour are homogeneous across the territory of the nation state. They all take for granted that this nation state is the relevant entity to consider. This is also why these measurements are obviously referred to as indices of nationalization. In fact, they actually measure a broader phenomenon, namely the territorial homogeneity of voting behaviour. That broader phenomenon can be analysed in any territory where there is an electoral competition between political parties and where figures are available on party offer and electoral results in smaller units than the one at which the electoral results are being aggregated. We will explore how territorial homogeneity has evolved in Belgium at the state level and at the level of the two major regions: Flanders and Wallonia. In order to do so, we will employ sPNS as it has proven to be the most reliable index developed so far (Andreadis, 2011).

Before discussing our model in more detail, we first present some historical background on Belgium’s territorial organization and the related evolution of the political parties. Both for the political parties and for the country itself, the history is one of territorial division. -

3 Belgium

Belgium is an interesting case for a discussion of the territorial homogeneity of electoral politics, mainly because of its unique party system. Political parties in Belgium are not present in the Belgian territory as a whole, but rather limit their electoral mobilization to either the Dutch-speaking northern or the French-speaking southern part of the country. This is, however, a fairly recent phenomenon. Until the late 1960s, the Belgian parties did present candidates in all districts. Yet these Belgian parties have split up into separate and unilingual parties. They did not do so in an attempt to adapt to a new state structure. To the contrary: it is under the already split party system that the final steps towards a federal Belgium – based on language groups – were taken. Parties actually adapted to internal divisions coinciding with the linguistic division of the country (Deschouwer, 2012; Verleden, 2009).1xThe small German-speaking community votes in the canton of Liege, for the Walloon party offer.

Belgium is indeed divided along linguistic lines (Witte, 1993). The north of the country – Flanders – is Dutch-speaking, while the southern region (Wallonia) is French-speaking. Brussels is a bilingual area and the third region in the Belgian federation. The linguistic divide has gradually become a politicized issue, mainly because the country was originally – after its creation in 1830 – organized in French. Debates and fundamental disagreements on the language used by the public authorities, on the exact boundaries between the linguistic areas (and, in particular, of the bilingual area of Brussels) and more recently also on the modalities of a federal reorganization of the state have driven the three major political parties apart. The Christian Democratic party had split in 1968, the Liberal Party in 1971 and the Socialist Party in 1978. Parties that were created after 1978 all limited their activities to one of the two language groups from the beginning. This means that there is one party system – parties competing against each other for voters – in the Dutch-speaking part of the country and another one in the French-speaking part of the country. In the Brussels region the two party systems are on offer, but they still cater mainly to voters belonging to their own language group.

Not only do the north and the south of Belgium have a separate party system, but these party systems are also significantly different. The other two cleavages have imbued Belgian party politics with a territorial flavour. The 19th century industrialization of the country took place mainly in Wallonia, while Flanders remained a rural area for a longer while, focusing on agriculture and small businesses. This resulted in a much stronger labour movement in the south, and thus a stronger socialist party. In Flanders, the Catholic and later Christian Democratic party became dominant. Until this day, Flanders votes more to the right, while Wallonia votes more to the left. However, it is not only the split of the major political parties that led to (potential) differences between the regions. Flanders and Wallonia also have a distinct electoral dynamic when it comes to extreme-right and regionalist parties. Historically, Flanders has a stronger presence of (very successful) radical-right (Vlaams Belang) and regionalist (Volksunie, N-VA) parties. Wallonia also had a radical-right party (FN), which was not nearly as successful as its Flemish counterpart and experienced a very turbulent history. The Walloon regionalist party (Rassemblement Wallon) was quite successful for a while in the 1960s and 1970s and even entered government in 1974. This actually created tensions between the more left-wing base and rather liberal leadership, eventually leading to internal divisions and the party’s swift demise (Van Dyck & Buelens, 1998). The fact that the party’s main competitor – the socialist party – had, in the meanwhile, become a new and unilingual party aided in the process by taking away RW’s electoral niche (Van Haute & Pilet, 2006).

The territorial split of the party system and of the electoral results has been reinforced by the transformation of Belgium into a federal state. Since 1995, regional parliaments for Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels have been directly elected and regional governments formed on the basis of the election results. In 1995 and 1999, the regional elections coincided with the federal ones, and coalitions were deliberately formed in a congruent way (Deschouwer, 2009; Stefuriuc, 2009). That is, the parties governing at the regional level were also included in the federal government. In 1995 the federal government was composed of the two Christian Democratic parties and the two socialist parties, each also governing in its own region. This pattern changed after the 2003 federal elections. Regional and federal coalitions became increasingly incongruent, while the federal government itself was now sometimes also non-symmetrical, implying that one party of the same party family is part of the federal government, while the other one stays in the opposition. These new patterns in coalition formation also mean that at the next elections the incumbent party families and opposition parties are different in the various regions. This has obvious consequences for voting behaviour. Electoral swings to and from parties and party families differ between north and south more often than before. Against this background, it is quite interesting to look at the way in which the homogeneity of electoral politics has evolved at the state and subnational levels. Even if it is quite evident that Belgium is a highly regionalized country in terms of the party offer, we still need to verify whether the electoral behaviour can be considered homogeneous within the regions. If it is true that the Belgian electorate does not have the technical possibility to behave truly nationalized because of the split party offer between regions, it is also true that it is entirely possible (and indeed our expectation) that within each region it would still be possible to observe a nationalized (or, more accurately, homogeneous) electoral behaviour. Or, to put it differently, if we fail to see a nationalized electorate at the national level, this is not the consequence of an incomplete nationalization, of the survival of local parties or of very different electoral responses at the local level. Therefore, if only a nationalized electoral offer allows for a nationalized electoral answer, it would be incorrect to claim that the electoral behaviour is denationalized in the case of Belgium – where the offer is exclusively regional – when considering only the country and ignoring the existence of two separate party systems.

In order to test whether the Belgian electorate is, as is our expectation, giving a homogeneous response to the regionalized party offer, we will test three hypotheses:H1: We expect nationalization to drop dramatically as the national party system splits;

H2: We expect that after the split of the party systems the territorial homogeneity in both regions will reach a high value (i.e. in line with the most nationalized national electorates in Western Europe)

While we expect high territorial homogeneity in both regions, we expect a higher level in Flanders. As mentioned earlier, Wallonia has a more leftist electorate, resulting from a long tradition of trade unionism since the early industrialization. Yet this industrialization was also limited within Wallonia to a belt between the cities of Liège and Charleroi, while other, less populated parts of Wallonia remained more rural. These areas vote more conservative.

H3: We expect that the territorial homogeneity will be higher in Flanders.

-

4 Methods and Data

The importance of treating an aggregate concept at the aggregate level has recently been emphasized by Welzel and Inglehart (2007). These scholars argue that ‘the fact that many characteristics affect individuals as aggregate attributes of their population, not as their personal attributes, is not an ecological fallacy but an ecological reality’ (Welzel & Inglehart, 2007, p. 306). This is undoubtedly the case for nationalization, as the nationalization of voter behaviour is an intrinsically aggregate concept. The whole idea of nationalization at the voter level relies on the very assumption that the citizens of a country vote in a homogeneous way. For this reason, all the indexes that measure nationalization use aggregate data. In this particular instance, the use of aggregate data does not lead to any ecological fallacy as the nationalization of voter behaviour is an inherently aggregate attribute of the voting population and the phenomenon that is under scrutiny does not have any micro-foundation that can be found at the individual level.

Because alternative indexes all face some problems (see above), we consider it useful to measure the territorial homogeneity levels of federal elections for Belgium, Flanders and Wallonia by employing the Bochsler index (2010). This index is based on the Party Nationalization Score (PNS) (Jones & Mainwaring, 2003), which is the inverse of the Gini index:

The PNS varies between 0 and 1 and allows for easy comparison between the different levels of nationalization, both in a synchronic (different levels of nationalization for parties within one election) and in a diachronic perspective (different levels of nationalization for a party over time). However, Bochsler (2010) identifies two problematic aspects of the PNS: this index does not take into account the size of territorial units across and within the country (it is obviously misleading to weigh two areas with very different shares of voters in the same way). The attempt to overcome these limits led to the elaboration of the Party Nationalization Score with weighted units (PNSw), which allows the correct comparison among different nationalization levels of parties in a country with differently sized territorial units. However, it was shown that the PNSw could deliver biased estimates because the estimates are affected by the aggregation level of the electoral data (Bochsler, 2010). In other words, when data at the regional level would be employed, the PNSw could estimate homogeneous levels of support, while the index could give a different final result when using a lower aggregation level (e.g. cities), showing that the result obtained by using data at the regional level was due to a large intraregional variance.

The sPNS solves this limitation by assuming that the heterogeneity measured at a lower territorial level, that is PNS(n2), corresponds to the squared heterogeneity measured at a higher level, that is PNS(n) – where n is the number of units. Thus, we have that:

A crucial step consists in introducing a logarithmic function in order to estimate the standardized level of party nationalization. The final result is the sPNS:

The sPNS is a revised version of the PNS, which includes raising the equation at 1/log(E), where E represents the number of effective territorial units, inspired by the number of effective parties introduced by Laakso and Taagepera (1979). Bochsler (2010) standardizes sPNS = PNS 10 under the assumption of a fixed number of electoral units that he defines as ten. The sPNS is the only existing index that does not show any variance when using different aggregation levels (Andreadis, 2011).

To compute the indexes, we measure at the level of the electoral canton. This is the smallest unit for which election results are available for Belgium. A canton comprises one or a few local municipalities. And each electoral district – the level at which lists are presented and seats are distributed – is composed of several cantons. In the analysis we include all the parties presenting a list in each canton, as registered by the Ministry of Interior.

We create an index for Flanders and Wallonia and also present a joint measurement for Belgium. The latter does not, however, really cover Belgium as a whole, but adds Flanders and Wallonia and leaves out Brussels. Not only has Brussels been one of the major stumbling blocs in Belgian politics, but it also poses problems for comparative and longitudinal research because of the shifting boundaries. Until 2014 the electoral district of Brussels was composed of the territory of the Brussels region and 35 local municipalities around Brussels that actually belong to the Flemish region (this only applies to federal elections, not the regional ones). After a long political crisis this electoral district was split, and for the 2014 elections there was a purely Brussels district for the very first time. In the figures we present for Flanders, we therefore also include this area of Flanders just outside Brussels, where until 2014 voters had the choice between the full array of both Francophone and Flemish political parties. In 2014 only one Francophone party (FDF) presented a list in the district of Flemish Brabant, to which these 35 municipalities now belong.

Excluding Brussels also means that the boundaries of the cantons coincide with the boundaries of the Brussels region. This has been the case since 1995. Until 1995 there were a few cantons that included municipalities from both Brussels and Flanders. We have excluded only those cantons that were purely Brussels cantons. Before 1995 there is thus also a little bit of Brussels in the figures for Flanders. This produces some minor and actually negligible noise for the results in Flanders (we have tested different alternatives), but for the Brussels region itself it is impossible to produce comparable figures over time. Excluding Brussels is therefore the only solution. Moreover, the sPNS index has an inherent limit: the calculation can be done for a maximum of 50 parties at a time, and in the case of the Brussels district this limit was exceeded for almost all the elections. We consider these reasons sufficiently valid to exclude Brussels and present Belgium as the sum of the Flemish and Walloon regions. This means we lose information on only 7.3% of the Belgian electorate.

In total, the electoral data of 194-198 cantons (the number varies across time) is analysed. Half of these cantons belong to Flanders and the other half to Wallonia. We consider 22 federal elections (1946-2014), always for the House of Representatives. The data is provided by the Belgian Ministry of Interior. -

5 Results

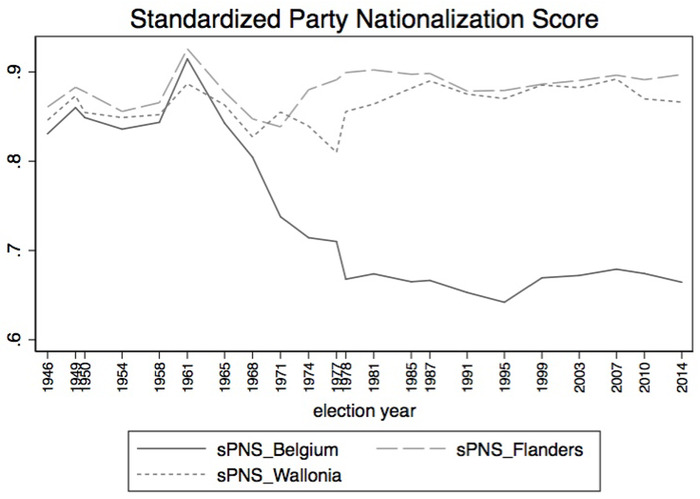

Figure 1 shows the standardized PNS for Belgium, Flanders and Wallonia. The figure leaves little doubt about what has happened. It shows the story of the changing relations between party offer and voter response in Belgium. It also shows us the crucial distinction to be made between nationalization at the level of the state and homogenization at the level of substate units.

Figure 1: Standardized Party Nationalization Score for Belgium, Flanders and Wallonia

The solid line represents Belgium (Flanders and Wallonia together) and measures nationalization as classically defined. This reaches a high point in 1961. From 1965 onwards, the degree of nationalization begins to drop. This turning point between 1961 and the next elections of 1965 reflects an important change. The 1965 elections were truly critical, representing the start of a severe fractionalization of the party system. Until then the party system could be labelled as a two-and-a-half-party system (Blondel, 1968), with a large Christian Democratic party (much larger in Flanders than in Wallonia) and a large socialist party (much larger in Wallonia than in Flanders). A smaller liberal party was the third or ‘half’ relevant party in the system, polling about 10% of the vote in each region. That liberal party did, however, reform itself in the wake of the 1965 elections, now also explicitly appealing to Christian voters. In 1965, the two largest parties both lost heavily and, for the first time, no longer controlled a two-thirds majority in Parliament. The reformed and renamed liberal party did quite well, but not in a homogeneous way. In Flanders it polled 17% of the votes, whereas in Wallonia it went up to 25%. This is a first element that pushes the degree of nationalization down. The second is more directly related to the language issue. From 1965 onwards, regionalist parties proposing a decentralization of the unitary state became electorally successful (De Winter, 1998; Van Dyck & Buelens, 1998; Van Haute & Pilet, 2006). In 1965 this was only the case in Flanders, where the Flemish regionalist party Volksunie (VU) jumped from 6 to 12% of the vote. On the Walloon side there was no similar breakthrough at the time. A Walloon regionalist party (Rassemblement Wallon) would only break through with 10% of the Walloon vote in 1968, when VU was at 17% in Flanders. Only in 1971 did both parties poll an equal score of 20% in their respective regions. The rise of regionalist parties therefore added to the decline of the Belgian electoral nationalization in two ways: by presenting themselves to the voters in their region only, and by not being equally successful and thus not equally affecting the results of the other parties. The same pattern applied to radical-right parties. Vlaams Belang (VB) first appeared in 1978 after splitting away from VU and remained unsuccessful during most of the 1980s. At the end of that decade the party started taking off at the local level (specifically in Antwerp) and had its first real breakthrough at the 1991 federal elections. The party continued to grow steadily until it reached a tipping point in 2006-2007. Front National (FN) also made its first appearance in 1991, but never achieved results comparable to VB. While VB was a disciplined party with a strong brand, deeply rooted in the historic Flemish Movement, FN lacked an organizational base and was ridden with divisive internal debates, ruptures and a very uneven electoral showing throughout its history (Deschouwer, 2012). Other small parties, such as the libertarian Lijst Dedecker (2007) in Flanders and the liberal–conservative Parti Populaire (2009) in Wallonia, have entered the electoral competition as well. Both were short-lived and had limited success and therefore also a limited impact on the index.

Between 1965 and 1981 the curve of the sPNS drops steeply for Belgium. This is no surprise, as it reflects the most fundamental change in the party offer. The three major state-wide parties (Christian democrats, socialists and liberals) now split up and became six non-state-wide parties. The demise of the Belgian socialist party in 1978 was the end point of that process, and from then on, the sPNS score stabilized at a very low level, also because of the appearance and varying degrees of success of radical-right and regionalist parties in Flanders and Wallonia. Only some very small parties still covered the Belgian territory. In 2014 the radical-left and state-wide Labour Party (PVDA-PTB) was able to elect two representatives in the House, but both were elected in Wallonia, where the party scored much better than in Flanders. It is important to remember that the de facto split offer between Flanders and Wallonia only has a direct impact on the sPNS score for Belgium as a whole. In order to have an effect on the regional sPNS scores, parties need to have more homogeneous or heterogeneous electoral support within the region over time, regardless of whether they are former national parties or not.

While the party offer is split at the level of the Belgian state, it gradually becomes more homogeneous at the regional level. During the two decades after 1965, the level of electoral homogeneity fluctuated a lot. That is mainly the consequence of the complex falling apart of the traditional state-wide parties and of the rise and (varying) success of the regionalist parties. Especially in Wallonia this process took longer to stabilize. The liberal party fell apart in different groups, some of whom allied themselves with the regionalists in some of the electoral districts. The socialist party also allied itself with the Walloon regionalist party in some places, therefore making a far from homogeneous offer to Walloon voters.

Between 1971 and 1981 there is a remarkable fluctuation in the sPNS score for Wallonia. During that period there is a clearly opposite trend in Wallonia (compared with Flanders). When looking at the electoral swings at the canton level, we see that the main culprit for this dip is Rassemblement Wallon, which scored relatively evenly throughout Wallonia while it was growing (1971-1974) but saw its support crumble very unevenly across the region when the party was in decline (1977-1978), with strong wins in some cantons and heavy losses in others. The variation in support stabilizes (geographically speaking) when the party’s electoral score hits rock bottom in 1981. By the end of the 1980s, both regions display a sPNS index that is quite high and fluctuates only minimally at that high level.

Our third expectation was that homogeneity would be lower in Wallonia than in Flanders. This is indeed the case, not only in the early years after the split of the major parties but also later on. This reflects former industrial Wallonia voting more to the left (socialist or extreme left) than the rest of the region. The electoral results in Flanders are more evenly spread over the territory. In 2003, the successor party to the Volksunie (Beyens et al., 2017 Noppe & Wauters, 2002) – the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA) – scored only 4.5% of the Flemish votes. In 2010 it went up to 28% and in 2014 up to 31%. Yet the degree of territorial electoral homogeneity in Flanders remained high, which means that this new party was able to attract voters all over the Flemish territory.

Both the structural differences between Flanders and Wallonia and the fact that subnational fluctuations point out – and inform us about – important dynamics regarding the electoral competition show that analyses regarding the territorial homogeneity of voter response should take place at the appropriate (party system) level rather than consistently focusing on the nation state. -

6 Conclusions

The literature on the nationalization of electoral politics has been dominated by discussions about the right way to measure it. Many different indicators have been developed, all trying to capture one or more dimensions of nationalization. Quite important in this respect is the attention for the party offer on the one side and voter response on the other. Clearly, the nationalization of electoral politics is a matter of electoral results. Yet electoral results are undeniably an answer of the voters to the party offer. If all parties are not available to all voters, the voter response cannot be homogeneous.

In this article we have illustrated this by looking at the nationalization of electoral politics in Belgium. In terms of the party offer, this is a quite peculiar country. Since the late 1960s it has had no (relevant) state-wide parties anymore. All parties are unilingual and compete for votes only within the Dutch- or French-speaking communities, each living in different territorial entities. Because of the institutional split of the Belgian party system, we decided to focus on voter response. We therefore measured the degree of nationalization of voter response not only at the Belgian level, but also at the level of the party offer, which are the regions of Flanders and Wallonia. Often the obvious unit of analysis for the study of nationalization is indeed the nation state, and degrees of nationalization are seen as an indicator of the degree of state and nation formation. However, applying a concept uncritically can be problematic and theoretically unjustified.

The term normally used for describing the homogeneity of electoral politics is nationalization. This is another way in which the nation state appears to be the obvious unit of analysis. Yet what all indicators of nationalization actually do is measure territorial homogeneity. This is, however, a feature that can be measured and analysed at levels other than that of the nation state as well. The wording thus leads to the evident – but sometimes misguided – unit of analysis. The Belgian case – just like any other case where there is a meaningful separate electoral competition in subnational territories – clearly illustrates that the relation between party offer and voter response should not be analysed at the state level alone. It also shows that taking into account the specificity of the case(s) is crucial in order to produce an accurate and meaningful analysis. The dynamics of party offer and voter response are visible at different levels and can have different meanings at these different levels. The historical analysis of Belgium has shown that at the Belgian level the degree of nationalization of voter response has decreased rapidly and dramatically in the 1960s. This is fundamentally – but not exclusively – the consequence of the choices made by the political parties. The Belgian electorate cannot offer a territorially homogeneous response to parties that are on the ballot paper in only half of the electoral cantons. The transformation – a full split – of the party offer has, however, created two new spaces for electoral competition. There are two party systems in Belgium, and for each of these systems the degree of territorial homogeneity can be analysed. The picture we drew of both Flanders and Wallonia is one of a very homogeneous voter response to the regional party offer. Both Flanders and Wallonia recovered to a high degree of homogeneity after the shock of the party splits subsided. The Belgian voters are thus responding in a very homogeneous way to the split party offer. This finding has two main implications, one practical and the other theoretical. From the practical side, we suggest that when surveying voting behaviour in Belgium (such as party attachment), the two regions should be considered separate, and therefore two samples should be extracted for the survey. Inhabitants of the two regions should be treated as living in different countries. From the theoretical side, we argue that the term nationalization is improper when referring to the electorate. We claim that it makes sense to talk about nationalization in function of the party offer only. As voting behaviour can only be an answer to that offer, it makes no sense to dispute whether it is nationalized or not, but only how homogeneous it is towards the given party offer. Our findings clearly show that a more careful use of terminology is necessary. If nationalization of voting behaviour is not necessarily happening at the level of the nation, one option would be to further stretch the concept of nationalization to fit subnational dynamics. We believe this to be a fool’s errand and advocate using a more generic and appropriate term like homogeneity of voter response, which also avoids the methodological nationalism that makes researchers blind to what is happening under the surface and beyond the nation state. This way, the label nationalization can be reserved for occasions when it is empirically and conceptually relevant, and not merely employed because analytical instruments are being utilized that were originally crafted to study nationalization and now serve a broader purpose. References Alemán, E. & Kellam, M. (2008). The nationalization of electoral change in the Americas. Electoral Studies, 27, 193-212.

Andreadis, I. (2011). Indexes of party nationalization. Paper presented at “The True European Voter” conference, Vienna, Austria, 23rd September.

Bartels, L. (1998). Electoral continuity and change. Electoral Studies, 17(3), 301-326.

Beyens, S., Deschouwer, K., van Haute, E., & Verthé, T. (2017). Born again, or born anew: assessing the newness of the Belgian New-Flemish Alliance (N-VA). Party Politics, 23(4), 389-399.

Blondel, J. (1968). Party systems and patterns of government in Western democracies. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 1, 180-203.

Bochsler, R. (2010). Measuring party nationalization: A new Gini-based indicator that corrects for the number of units. Electoral Studies, 60, 155-168.

Butler, D., & Stoke, D. (1969). Political change in Britain: Basis of electoral choice. New York: St Martin Press.

Caramani, D. (1996). The nationalization of electoral politics: a conceptual reconstruction and review of the literature. West European Politics, 19(2), 205-224.

Caramani, D. (2004). The nationalization of politics. The formation of national electorates and party systems in western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Caramani, D. (2006). Is there a European electorate and what does it look like? Evidence from electoral volatility measures, 1976–2004. West European Politics, 29(1), 1-27.

Chibber, P. and Kollman, K. (1998). Party aggregation and the number of parties in India and in the United States. American Political Science Review, 92(2), 329-342.

Chibber, P., & Kollman, K. (2004). The formation of national party systems: Federalism and party competition in Canada, Great Britain, India, and the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Claggett, W., Flanigan, W. & Zingale, N. (1984). Nationalization of the American electorate. American Political Science Review, 78(1), 77-91.

Converse, P.E. (1979). Survey research and the decoding of patterns in ecological data. In: M. Dogan and S. Rokkan (Eds.) Quantitative ecological analysis in the social sciences. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cox, G.W. (1999). Electoral rules and electoral coordination. Annual Review of Political Science, 2, 145-161.

Deschouwer, K. (2009). Coalition formation and congruence in a multi-layered setting: Belgium 1995-2008. Regional and Federal Studies, 19(1), 13-35.

Deschouwer, K. (2012). The politics of Belgium. Governing a divided society. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

De Winter, L. (1998). The Volksunie and the dilemma between policy success and electoral survival in Flanders. In L. De Winter & H. Türsan (Eds.), Regionalist parties in western Europe (pp. 28-50). London: Routledge.

Firebaugh, G. (2003). The new geography of global income inequality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Flora, P., Kuhnle, S. & Urwin, D. (1999). State formation, nation-building and mass politics in Europe. The theory of Stein Rokkan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gini, C. (1921). Measurement of inequality income. Economic Journal, 31(1), 124-126.

Jeffery, C. & Schakel, A. (2013). Towards a regional political science. Regional Studies, 47(3), 299-302.

Hoschka, P. and Schunck, H. (1978). Regional stability of voting behaviour in federal elections: A longitudinal aggregate data analysis. In: M. Kaase and K. von Beyme (Eds.) Elections & Parties. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication.

Jeffery, C. & Wincott, D. (2010). The challenge of territorial politics: Beyond methodological nationalism. In C. Hay (ed.), New directions in political science: Responding to the challenges of an interdependent world (pp. 167-188). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Johnston, R. J. (1981). Testing the Butler-Stokes model of a polarization effect around the national swing in partisan preferences: England, 1979. British Journal of Political Science, 11(1), 113-117.

Jones, M. P. & Mainwaring, S. (2003). The nationalization of parties and party systems. An empirical measure and an application to the Americas. Party Politics, 9(2), 139-166.

Katz, R. S. (1973). The attribution of variance in electoral returns: An alternative measurement technique. American Political Science Review, 67(3), 817-828.

Kasuya, Y. & Moenius, J. (2008). The nationalization of party systems: Conceptual issues and alternative district-focused measures. Electoral Studies, 27, 126-135.

Kawato, S. (1987). Nationalization and partisan realignment in congressional elections. American Political Science Review, 81(4), 1235-1250.

Laakso, M., & Taagepera, R. (1979). Effective number of political parties: A measure with application to West Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 12(1), 3-27.

Lee, A. (1988). The persistence of difference: Electoral change in Cornwall. Paper presented at the Political Studies Association Conference, Plymouth, UK.

Lago, I. & Montero, J. R. (2009). The nationalization of party systems revised: A new measure based on parties’ entry decisions, electoral results and district magnitude. Paper presented at III Congreso Internacional de Estudios Eletorales, SOMEE, Salamanca.

Moenius, J. and Kasuya, Y. (2004). Measuring party linkage across districts. Party Politics, 10(5), 543-564

Morgenstern, S., Hecimovich, J. P. & Siavelis, P. M. (2014). Seven imperatives for improving the measurement of party nationalization with evidence from Chile. Electoral Studies, 33, 186-199.

Morgenstern, S., & Potthoff, R. (2005). The components of elections: District heterogeneity, district-time effects, and volatility. Electoral Studies, 24, 17-40.

Morgenstern, S., Swindle, S. M. & Castagnola, A. (2009). Party nationalization and institutions. The Journal of Politics, 71(4), 1322-1341.

Mustillo, T. & Mustillo, S. (2012), Party nationalization in a multilevel context: Where’s the Variance? Electoral Studies, 31, 422-433.

Noppe, J. & Wauters, B. (2002). Het uiteenvallen van de Volksunie en het ontstaan van de N-VA en Spirit. Res Publica, 2-3, 397-471.

Rae, D.W. (1967). The Political Consequences of Electoral Laws. London: Yale University Press.

Rokkan, S. (1970). Citizens, elections, parties: approaches to the comparative study of the processes of development. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget (reprinted by ECPR Press in 2009).

Rose, R. & Urwin, D. W. (1975). Regional differentiation and political utility in Western nations. Contemporary Political Sociology Series, N. 06-007. London and Beverly Hills: Sage.

Russo, L. (2014). The nationalization of electoral change in a geographical perspective. The case of Italy (2006-2008). GeoJournal, 79(1), 73-87.

Russo, L., Dolez, B., & Laurent, A. (2013). Presidential and legislative elections: How the type of election impacts the degree of nationalization. The case of France (1965-2012). French Politics, 11(4), 356-372.

Schattschneider, E. (1960). The semisovereign people. A realist’s view of democracy in America. Chicago: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Stefuriuc, I. (2009). Introduction: Government coalitions in multi-level settings – institutional determinants and party strategy. Regional and Federal Studies, 19(1), 1-12.

Stokes, D. (1965). A variance components model of political effects. In J. M. Claunch (ed.), Mathematical applications in political science. Dallas: Southern Methodist University.

Stokes, D. (1967). Parties and the nationalization of electoral forces. In W. N. Chambers & W. D. Burnham (Eds.), The American party systems: States of political development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Van Dyck, R. & Buelens, J. (1998). Regionalist parties in French-speaking Belgium: The Rassemblement Wallon and the Front Démocratique des Francophones. In L. De Winter & H. Türsan (Eds.), Regionalist parties in Western Europe (pp. 51-69.). London: Routledge.

Van Haute, E. & Pilet, J. B. (2006). Regionalist parties in Belgium (VU, RW, FDF): Victims of their own success?. Regional and Federal Studies, 16, 297-314.

Verleden, F. (2009). Splitting the difference: The radical approach of the Belgian parties. In W. Swenden & B. Maddens (Eds.), Territorial party politics in Western Europe (pp. 145-166). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Welzel, C. & Inglehart, R. (2007). Mass beliefs and democratic institutions (pp. 279-313). In C. Boix & S.C. Stokes (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Witte, E. (1993). Language and territoriality. A summary of developments in Belgium. International Journal on Minority and Group Rights, 1(3), 203-223.

Noten

-

1 The small German-speaking community votes in the canton of Liege, for the Walloon party offer.