Transformative Welfare Reform in Consensus Democracies

-

1 Introduction1xWe thank two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and Chris Vermorken and Stefano Ronchi for their research assistance.

Patterns of Democracy, Lijphart’s magnum opus from 1999 (new edition of 2012), is one of the most influential books in the field of comparative political science, making three distinct contributions. First, Lijphart inductively constructed a new typology of democracy, based on ten variables, that yielded two dimensions, according to which 36 democracies could be classified as either majoritarian or consensus types of democracy. Second, he used this difference between majoritarian and consensus democracy to challenge the conventional wisdom that there is a trade-off between the quality (e.g. proportionality of representation and more participation as in consensus democracies) and the effectiveness (e.g. swifter and more resolute decision-making as in majoritarian democracies) of democratic government. In the first edition of Patterns, Lijphart reached the negative conclusion that ‘majoritarian democracies are clearly not superior to consensus democracies in managing the economy and in maintaining civil peace’ (p. 274, original emphasis). Third, he claimed that of the two types, consensus democracy is the ‘kinder, gentler’ form of democracy. Consensus democracies

are more likely to be welfare states; they have a better record with regard to the protection of the environment; they put fewer people in prison and are less likely to use the death penalty; and the consensus democracies in the developed world are more generous with their economic assistance to the developing nations. (pp. 275-276)

Focusing on welfare state reform efforts, in particular with respect to the paradigmatic policy turn to social investment, we pose the following questions: does consensus democracy continue to produce kinder, gentler social policies, and if so, why and how? With respect to the why and how, we aspire to be more specific than Lijphart by highlighting the institutional process characteristics of consensus democracies, bearing on their capabilities – or lack thereof – in fostering transformative change.

With transformative change, we refer to the kind of gradual policy changes that significantly break with policy legacies in an attempt to amend the unintended yet harmful pathologies of the existing welfare state regime, such as the ‘welfare without work’ syndrome of the continental welfare state (Esping-Andersen, 1996b). Most European welfare states have been reconfiguring the policy mixes upon which they were built after World War II. Significant social investment reform took place in consensus democracies belonging to the conservative-corporatist welfare regimes on the European continent, but more so in some (the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany) than in others (Italy). Social investment reform has been much more difficult to venture or sustain in majoritarian democracies, such as the United Kingdom (UK), a liberal welfare state, and France, another continental welfare state.

Our take on Lijphart’s kinder and gentler consensus democracy thesis is motivated by a combination of three propositions:Consensus democracies are better in processing transformative welfare reform in a social investment direction.

Social investment reform, because of its transformative nature, especially in insurance-based continental welfare states, requires a capacity to govern for the long term.

Consensus democracies harbour capabilities to govern for the long term.

It is noteworthy that this goes beyond Lijphart’s classical thesis. Lijphart simply found that consensus democracies were associated with more social spending and less inequality than were majoritarian systems. However, he did not develop an argument about the institutional architecture of welfare regimes conducive to these outcomes, nor did he address the issue of the reform capability and mechanisms producing the outcomes.

The article proceeds as follows. First, we critically discuss Lijphart’s typology and the kinder, gentler hypothesis. We argue that there are good reasons to assume that certain features of consensus democracy produce a kinder, gentler form of democracy, in both policy substance and style of decision-making. Next, we document the social investment turn. We then theorize why and under what conditions consensus democracies are better in pursuing transformative reform, identifying the institutional features that can surmount the temporal uncertainty in the politics of social investment and hence allow governing for the long term. We then illustrate the proposition with short case descriptions of the Netherlands and Belgium. We conclude by stressing that Lijphart’s kinder, gentler hypothesis is still relevant, but hinges on the recognition that there is a real need for empirical and theoretical qualification beyond simple correlations, and that we need to focus on the process qualities of consensus democracies that condition the capacity for transformative policy change. -

2 Lijphart’s typology and the kinder, gentler hypothesis

Patterns of Democracy attracted a great deal of persistent conceptual, theoretical, methodological and empirical criticisms, jeopardising practically the entire original enterprise. What is worrying is the fact that replicating Lijphart’s results is impossible. Replication failure emerges when one extends the case selection to other countries (Central and Eastern European democracies; Fortin, 2008; Asian countries; Croissant & Schächter, 2009). Similarly, results look very different if one studies other time periods for the same or a similar set of countries that Lijphart used (Vatter, 2009; Vatter & Bernauer, 2009). Finally, the impact of consensus democracy on macroeconomic and government performance turns out to be driven entirely by corporatism (see Giuliani, 2016).

A recent study concludes that we should stop speaking of the consensus versus majoritarian dimensions of democracy. ‘When concepts refer to patterns that do not really exist in the observable world,’ writes Coppedge (2018, p. 24), ‘they are not useful and should be abandoned’. Coppedge is equally dismissive of the kinder, gentler hypothesis (Coppedge, 2018, p. 3).

This seems too harsh a judgment. First, Lijphart reported significant correlations between consensus democracy and a range of democratic and socio-economic performance markers (Bogaards, 2017), including major indicators of the welfare state. Second, other studies have found a positive and significant impact of consensus democracy on the welfare state and income inequality (Birchfield & Crepaz 1998; Crepaz, 1998; Tavitz, 2004). Third, Roller (2005, p. 133) found that many of the effects Lijphart reported disappear when one applies the appropriate statistical criteria for the hypotheses tests. However, this is not the case in the social policy realm, where consensus democracies perform clearly superiorly, even when stringent statistical standards are applied. In the area of the welfare state, Lijphart’s and others’ findings are robust.Table 1 Consensus democracy and social spending, 2010Country Executive-parties dimension, 1981-2010 Public social spending, 2010 (% GDP) United Kingdom -1.48 22.40 Canada -1.03 17.50 France -0.89 31.00 Australia -0.65 16.60 Spain -0.63 24.70 United States -0.63 19.40 Greece -0.55 24.90 New Zealand -0.17 20.40 Portugal 0.04 24.50 Ireland 0.38 24.60 Luxembourg 0.38 23.10 Iceland 0.55 16.90 Germany 0.63 25.90 Austria 0.64 27.60 Japan 0.71 21.30 Sweden 0.87 26.30 Norway 1.09 22.00 Belgium 1.10 28.30 Italy 1.13 27.10 Netherlands 1.17 17.80 Denmark 1.35 28.60 Finland 1.48 27.30 Switzerland 1.67 15.10 Note: Countries are ranked according to their score on the executive-parties dimension.

Sources: Lijphart (1999 [2012], pp. 305-306); OECD. Retrieved 12 February 2019, from, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SOCX_AGG.Moreover, there are some further good reasons, although with important nuances, to expect that consensus democracy produces a kinder, gentler form of democracy. As Table 1 illustrates, most highly developed welfare states (in terms of social spending) are consensus democracies in the sense that they score positively (and mostly above average) on Lijphart’s executive-parties dimension. However, certainly not all consensus democracies are equally well-developed welfare states. Switzerland, for instance, had the highest consensus democracy score (1.67) but the lowest public social spending in 2010 (15.1% of GDP). Second, the typical liberal and lean welfare states (the UK, Canada, Australia, the United States and New Zealand) with below-average social spending in 2010 (<23% of GDP) are all majoritarian systems with negative scores on Lijphart’s executive-parties dimension. The major outlier here is France, which is the biggest welfare state in terms of social spending (31% of GDP in 2010) but has a negative score on the consensus democracy dimension. The correlation between the two variables is low (0.12) but extremely dependent on the French and Swiss cases. Removing both of these cases increases the coefficient to almost 0.5.

2.1 Why should consensus democracy produce a kinder, gentler form of democracy?

There is huge variation in welfare state development among countries that have similar levels of democratic development. This observation alone should trigger our comparative political science instinct that diverse types of democracy foster different social policy regimes and outcomes. This was, of course, Lijphart’s motivation for hypothesizing that consensus democracy tends to be the kinder, gentler form of democracy.

Lijphart explained the theoretical reason by exploring the ramifications of the dictum that democracy is government by, but also for the people. Lijphart (1999 [2012], p. 1) started with the fundamental question: ‘who will do the governing and to whose interest should the government be responsive when the people are in disagreement and have divergent preferences?’ There are two possible answers to the cui bono question: the majority of the people or as many people as possible. Democratic systems that systematically cater to as many people as possible produce a kinder, gentler form of democracy.

Lijphart, however, did not clearly elaborate the causal mechanisms, but suggested that a number of specific features of consensus democracy might facilitate kindness and gentleness in outcomes. Consensus democracies have a ‘strong community orientation’ and ‘social consciousness’. Moreover, consensus democracies work with ‘connectedness’ and ‘mutual persuasion’ rather than on the basis of ‘self-interest’ and ‘power politics’, producing a more feminine model of democracy (Lijphart, 1999 [2012], pp. 293-294).

Much more than these suggestions, however, one does not find in Patterns. Does there not exist a better way of theoretically specifying the relationship between democratic institutions and welfare state outcomes? This question has been central in the political economy literature on the welfare state, to which we turn next.2.2 Democracy and the welfare state

Why would one expect democracy to be related to social policy and the welfare state at all? The intuitive answer is that democratization opens up the political system to ‘ordinary’ people, who express demands for social protection and redistribution of income. Citizens will try to improve their situation via political means. If voters rationally vote in accordance with their preferences for social protection and income redistribution and if the political system is responsive, then democracy should lead to social policy extensions, the welfare state and, ultimately, to less poverty, higher income equality and more social protection.

Meltzer and Richard (1981) formalized this intuition. In a society with a right-skewed unequal income distribution, the median income will always be lower than the mean income. As a result, median voters can improve their income position by voting for a party that promises them income redistribution from the rich(er) to the poor(er) segments of society. In a competitive set-up, political parties will converge towards the wishes of the median voter, and the victorious party will introduce redistributive policies that satisfy the median voter’s demands.

The Meltzer-Richard model predicts that the more unequal a country is, the more the median voter in that country stands to gain by redistribution and the higher the level of income redistribution will be. However, precisely the opposite is the case empirically: countries with the lowest market income inequality redistribute the most income. Lindert (2004, p. 15) aptly labelled this particular finding the ‘Robin Hood’ paradox: ‘redistribution from rich to poor is least present when and where it seems to be most needed.’

The welfare state literature has tried to find a solution to the Robin Hood paradox. Perhaps the median voter cares less for income redistribution than for social protection (Rehm, 2011). Maybe the median voter is not so decisive and redistribution depends more on the mobilizing strength of political actors that organize poorer segments of society. The power resources approach stresses that well-organized labour unions and strong parties of the left in government both moderate market inequality and promote further income redistribution via the welfare state (McCarthy & Pontusson, 2009).2.3 Electoral institutions matter for welfare state outcomes

The welfare state literature provides a number of theoretical arguments that could help underpin Lijphart’s intuition that consensus democracy produces welfare state outcomes, which are kinder and gentler than those of majoritarian democracy. What matters most is whether the electoral system is proportional or majoritarian.

Iversen and Soskice (2006) started from the empirical observation that proportional electoral systems with multiple parties are more favourable to left governments than majoritarian electoral systems with two-party systems. The right flourishes most under majoritarian systems with two parties. Why does this occur? The answer is that the two electoral systems provide middle-income voters with radically different options when deciding whether to vote for the left or for the right.

If the left is in power in a two-party system, the party is likely to tax only middle and upper echelons of the income distribution, in order to redistribute income from higher- to the lower-income groups. Middle-income voters, faced with this possibility, fear that under a left government they will pay high taxes, but get not much, if anything, in return. Their safe bet is to vote for the right. If the right governs, middle-income voters would not receive benefits, but they would not be taxed heavily either.

Under proportional representation and a multiparty system, the choice for middle-income voters is radically different. Because there are multiple parties, middle-income voters have the option to vote for a party that exclusively represents their interests and that can be trusted and held responsible at the next election for the tax and benefit policies it pursued. The party that represents middle-income voters could link up with the left party. It will then levy taxes on middle-income voters and the rich, but it will only do so under the condition that the benefits will also flow to middle-income voters. If the party supported by middle-income voters allies with the right, the centre-right government would not tax the middle-income voters much, but it would not provide benefits either. If middle-income voters are interested in benefits and services such as healthcare and education, their best option is to support a centre-left coalition.

Hence, under proportional representation and multiparty democracy, the centre-left will be in power more often, and redistribution and equality will be higher and poverty lower than under majoritarian, two-party democracy.

However, there is still significant variation in redistribution, economic inequality and poverty among the countries with proportional representation and multiple parties. This shortcoming can be remedied by appreciating that majoritarian electoral rules and two-party systems really leave room only for the articulation of the labour-capital cleavage, which dominates politics. Under proportional rules, however, parties articulate and represent more conflict dimensions. The redistributive outcome then becomes dependent on which other cleavages are present in the system, how this affects the middle-income voters’ political behaviour, and which coalitions emerge in favour or against redistribution (Van Kersbergen & Manow, 2009). -

3 Transformative change: The social investment turn

From the 1990s onwards, the comparative welfare state literature increasingly focused on how welfare states cope with demographic ageing, intensified economic internationalization and disruptive technological change.

Research expected that social policy adjustments would follow welfare regime-conforming trajectories of incremental (non-)change (Esping-Andersen, 1996a; Pierson, 1996). The liberal Anglo-Saxon welfare states, with the United States as an example, were to experience persistent downward pressures on wages for low-skilled workers, reinforcing poverty traps. The Nordic welfare states would suffer from an undersupply of skilled and educated workers, because extremely high levels of taxation imply severe disincentives to work more hours. The continental welfare states – prevalent in France, Germany, Austria and the Benelux – were likely to experience the predicament of ‘welfare without work’ because industrial restructuring led to large-scale labour shedding, buffered by traditionally male-breadwinner social insurance arrangements.

However, things turned out differently. Rather than lock-in and institutional inertia, the emergence and spread of a novel social policy paradigm – social investment – far better characterizes welfare state reform in many countries (Hemerijck, 2017; Van Kersbergen & Hemerijck, 2012). Social investment reform conjures up a transformation from a passive welfare state that is proficient in buffering social and life course risks through social security, to portfolios of capacitating social policies that are future oriented. Social investments are – literally – investments in the development, enhancement, allocation and protection of human capital that are meant to yield inclusive, medium- and long-term socio-economic returns in knowledge economies and ageing societies.

The main idea of the social investment paradigm is that it is better to prepare than to repair. Social policy should assist individuals to adapt to the new risks associated with deindustrialization, globalization and the feminization of employment. The objective is to increase human capital to adapt the labour force to a period when changes are fast (knowledge economy). The social investment approach tilts the welfare balance from ex-post compensation in times of economic or personal hardship to ex-ante risk prevention. In the European context, an ever greater number of countries have pursued such social investment reform strategies. To a surprising extent, many countries have recalibrated and complemented established social protection programmes with employment- and family-friendly social policies (Hemerijck, 2013).

Early investments in children through high-quality education and care translate into higher levels of educational attainment, which, in turn and together with tailor-made vocational training, spill over into higher productive employment in the medium term. Effective work-life balance policies, including adequately funded and publicly available childcare, support employment participation and yield higher levels of female employment with lower gender pay and employment gaps. More opportunities for women and men to combine parenting with paid labour dampen the so-called ‘child gap’, the difference between the number of children families desire and the actual number of children (Bernardi, 2005). Active ageing policies, including portable and flexible pensions as well as measures to discourage early retirement, raise the retirement age. Higher and more productive employment implies a larger tax base to sustain welfare commitments and to keep the virtuous cycle of social investment alive.

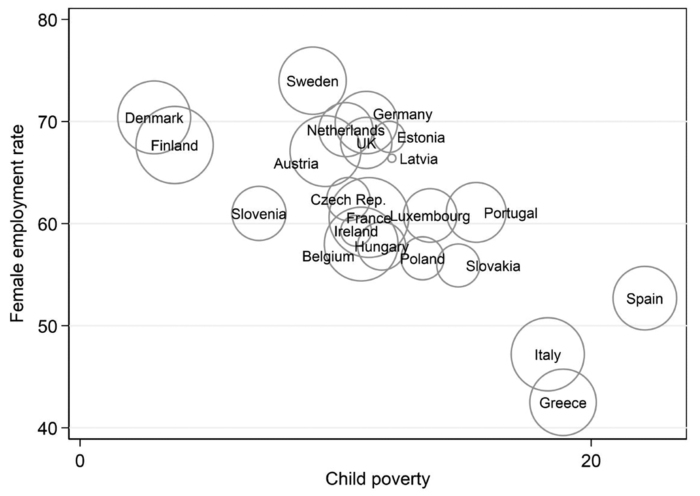

To illustrate, Figure 1 plots a selection of EU countries according to their female employment rates and levels of child poverty, showing that those with record female employment also have low child poverty and relatively large welfare states. The Nordic welfare states outperform the rest, but the continental countries Germany, Austria and the Netherlands also do relatively well. Some big spenders (France and Belgium) do well in terms of child poverty but have failed to reach high levels of female employment. Southern European countries fall short of both objectives, having low employment and high poverty despite sizeable welfare spending.Figure 1: Female employment, child poverty and public social spending Note: The size of the bubbles in the graph is proportional to welfare spending in each country, ranging from the ‘smaller’ welfare state in Latvia (14.4% of the GDP) to the ‘biggest’ in France (31.7% of the GDP) [adapted from Hemerijck & Ronchi, forthcoming].

Note: The size of the bubbles in the graph is proportional to welfare spending in each country, ranging from the ‘smaller’ welfare state in Latvia (14.4% of the GDP) to the ‘biggest’ in France (31.7% of the GDP) [adapted from Hemerijck & Ronchi, forthcoming].

Historically, there is significant variation in the timing and direction of social investment reform across countries, largely contingent on their path-dependent welfare-policy legacies. The vanguard universal Nordic welfare states were already in the lead in the 1980s. The liberal ‘bandwagon’ British welfare state followed suit in the late 1990s under New Labour. The continental welfare turn to social investment progressed in a far more ambiguous way. This is because the continental welfare state is by design far more wedded to employment-based insider-status social insurance, male-breadwinner families, a lack of social services (child care, active labour market training, reintegration services), and a more conservative stability-oriented macroeconomic policy stance. Most continental welfare states opted for labour supply reduction through early retirement and a generous application of disability pensions, while discouraging women from entering the labour market.

To the extent that continental welfare states turned to social investment, this amounts to a veritable U-turn in welfare state design. Although policy failure (‘welfare without work’) induced the continental social investment overhaul, it did not abruptly arise in response to any deep economic or social crisis. It is rather an example of what Streeck and Thelen (2005) call transformative institutional change, which takes place over a long period of time and through a series of incremental but cumulative reforms across a host of policy areas. -

4 The predicament of governing for the long term

Because continental welfare states, with the exception of France and, to some extent, Italy, comprise consensus democracies with a proportional electoral system, it is pertinent to ask which institutional features of consensus democracy enable the transformative welfare state change towards the outcome of social investment. In our survey of the literature, we adopted a comparative statics perspective. However, to understand the political dynamics of social investment reforms more fully, we must complement this perspective with a dynamic understanding of the processual character of the style and substance of consensus democracies. Our proposition is that consensus democracies based on proportional representation, coalition governments, and – not to forget – social partnership, allow for negotiated and long-term-oriented reform compromises, which can ensure that the costs and burdens of intrusive long-term-oriented social investment reforms are fairly shared.

The move to social investment indicates that governments have been able to reform for the long term. Social investment policy reform presumes that governments are willing and capable of shifting policy efforts from prevailing compensatory social security arrangements to social investments that promise long-term gains for all. This is obviously a strong assumption because we know that political (electoral) cycles have a short time span and that governing for the long term is not easily forthcoming.

Three important factors contribute to the predicament of political short-termism (Jacobs, 2016). First, voters know more about today’s policy consequences than they do about those in the longer term; they face informational obstacles to making prospective (rather than retrospective) judgments. Similarly, political elites, as vote seekers, are drawn to current problems. Moreover, the future is – per definition – more uncertain than the present. Second, long-term political commitment is fragile. Finally, a policy investment that imposes immediate distributive costs on particular groups makes it likely that these groups resist reform efforts that trample with existing rights and status positions.

Temporal uncertainty in the politics of governing for the long term comes in cognitive, distributive and institutional dimensions. Cognitively, it is difficult to decide which social investments obtain the highest social return in the future. In distributive terms, upfront costs are measurable, but future benefits are likely to remain a pie in the sky for quite some time. Interestingly, citizen opposition to costly public undertakings does not arise from the intrinsic hostility to taxation or indifference to public goods provision, but from the delegative, institutional character of investment-oriented reforms. Citizens lack the confidence that public officials, who impose tangible reform costs today, will later be able to deliver effectively on the public goods they promise (Jacobs & Matthews, 2017).

Governing for the long term is difficult, but not impossible (Jacobs, 2011). Reorienting welfare provision towards social investment constitutes a complex reform endeavour that raises daunting political dilemmas, even in the purview of long-term Pareto optimal outcomes. So how has it been possible, albeit with considerable cross-national variation, that social investment reform has progressively taken root?

The theoretical literature directs our attention to processual political conditions under which political actors may be able to overcome the cognitive, institutional and distributive obstacles for devising effective temporal policies and reforms for the long term. Shortly summarized, long-term-oriented social policies and reform need to be organized such that they can ‘(a) enhance the cognitive quality of information about long-run consequences, (b) stabilize institutional commitments over time, and (c) muster distributive compromise or minimize distributive opportunism by affected groups’ (Jacobs, 2016, p. 442). Finally, for the case of social investment reform per se, we add the normative dimension that relates to the value of work and gender relations. Social investment reforms must rally support for a profound change in traditional gender relations, if it is to promote dual earner families and gender equality in employment relations.

Any future-oriented social investment reform confronts historical legacies and path dependencies, often in conjunction with fiscal constraints from pre-existing social spending commitments (Pierson, 2004). The timing of social investment reform is critical because existing commitments to old welfare programs pre-empt the development of new capacitating social policies (Bonoli, 2007). In hindsight, only a few Nordic countries have had the luxury of possessing the conditions that allowed them to redirect social policy efforts towards social investment. Social investment reform arose in the Nordic countries before the fiscally constrained 1990s. Governments elsewhere aspiring to follow suit thereafter inescapably faced serious difficulties in introducing capacitating and employment-oriented services and family policies, leaving cost containment and institutional liberalization as the major rationale for reform, because the policy space for social investment recalibration was meanwhile crowded out by standing commitments and austerity (Palier & Thelen, 2010). In other words, there are reasons to remain sceptical about the political capacities of advanced democracies to facilitate transformative welfare state change, given temporal, welfare architectural and fiscal constraints. -

5 Governing the U-turn: From ‘welfare without work’ to social investment

A tight link between employment performance and/or family status and social entitlements characterized the continental, Bismarckian welfare states. Social entitlements were employment related via social insurance, often occupationally distinct and catered to the traditional single-earner family (Van Kersbergen, 1995). Benefits for male breadwinners were generous and covered a long period. From the 1980s onwards, continental regimes attempted to fight mass unemployment by resorting to strategies of labour supply reduction. Luring people out of the labour market by facilitating early retirement, increasing benefits for the long-term unemployed, lifting the obligation for older workers to seek employment, discouraging mothers from seeking employment, favouring long periods of maternity leave, easing access to disability pensions and reducing working hours created the ‘welfare without work’ syndrome (Hemerijck & Eichhorst, 2010).

One important condition for initiating path-breaking reforms is that social and political actors recognize and acknowledge that the labour reduction strategy is a self-defeating policy. It increases public social expenditure and labour costs and at the same time discourages labour market participation. In the course of the 1990s, main actors (unions, governments, parties, think tanks) gradually came to realize that continuing on the labour reduction route was a policy failure and implied an existential threat to the welfare state.

However, such a recognition of policy failure is not a sufficient condition for the introduction of path-breaking reforms. In addition, a novel policy consensus needs to be constructed that promises to overcome the vicious circle of ‘welfare without work’, while new political coalitions need be to be forged that can support it.

Obviously, once political actors cognitively realized that the ‘welfare without work’ syndrome’s most devastating feature was the self-defeating labour reduction strategy, the new policy goal had to become the maximization of labour market participation. The new overall policy goal triggered a long, complex but ultimately cumulative reform agenda, which included containment of wages and social spending, trimming of pensions and passive benefits, reductions in payroll charges, the introduction of active incentives, updates to family policies, increased means-testing, and labour market deregulation to overcome insider/outsider cleavages (Palier, 2010). However, not all countries started moving at the same time and with the same speed in recognizing policy failure, adopting a new policy goal, and reorganizing political coalitions in support of path-breaking reforms.5.1 The Netherlands

Under conditions of mass unemployment and declining union membership, unions and employers organizations revitalized corporatist negotiations between the social partners and the government in the early 1980s to introduce an alternative for labour reduction. These actors agreed on a policy package that combined wage restraint, cuts in social benefits and first steps towards activation with an expansion of flexible, part-time, service-sector jobs (Visser & Hemerijck, 1997). Although long-term wage restraint caused stagnant primary sector wages, the additional takings that women brought in compensated for loss of household income.

The massive entry of Dutch women into the labour market was possible only because of the changing status of part-time work. Women increasingly took up part-time jobs in the expanding service sector that also enjoyed full collective bargaining coverage. By the turn of the century, three-quarters of all female workers had part-time jobs. From the early 1990s, policy actors, especially trade unions, were keen to normalize part-time work with pension rights and collective bargaining. The so-called ‘flexicurity’ agreement between the trade unions and the employers in 1995 struck a winning balance between flexible employment (afforded by safeguarding social security and the legal position of part-time and temporary workers) and a slight loosening of employee dismissal legislation (Houwing, 2010).

One of the most pathological elements of the ‘welfare without work’ syndrome in the Netherlands concerned abuse of sickness insurance and disability pensions for shedding workers. To attack this, social insurance schemes were made more costly to employers, activation was extended and elderly unemployed were required to look for work.

Following the part-time work revolution, policies of reconciling work and family life gained prominence. Dutch childcare is characteristically a matter of subsidies, tax deductions and exhortations to make employers pick up the bill. In 2005, the Christian Liberal government expanded childcare by creating additional facilities at schools and by paying one-third of childcare costs. In 2006, a new Christian Social Democratic coalition made contributions obligatory. A generous tax rebate subsidy scheme proved so popular and costly that the government felt forced to scale it down after 2008.

The 2008 global financial crisis hit the Netherlands hard. Four large financial institutions had to be bailed out, creating immediate budgetary problems. In 2012, economic projections signalled a higher deficit than the EU 3% norm. A new coalition between the liberal party and the social democratic party launched a fiscal austerity program and embarked on a new wave of reforms that included social insurance cuts, healthcare retrenchment, housing and education reform and further labour market liberalization. The Participation Act of 2015 decentralized key functions of implementation, activation, employment reintegration and poverty alleviation to the municipalities. Some social investment policies were preserved, such as an extension of paid maternity leave and granting employees the right to reduced hours with special entitlements for parents with small children. However, major cuts in childcare expenditure caused a decline in childcare uptake and a shift to informal care provision. The financial crisis episode therefore epitomizes an element of ambiguity in the Dutch social investment turn.

Politically, however, social investment reform in the Netherlands could rely on strong consensus between mainstream parties and trade union and employers’ organizations. The social partners agreed on long-term wage restraint and accepted that consecutive centre-right and centre-left governments would close off the early-exit routes. They also tacitly accepted the increase in the retirement age to 67. Even though activation was a brainchild of social democracy, subsequent conservative governments never really challenged the activation turn. Female employment moved from the lowest to the highest level in Europe, and this generated further societal and political demands for improvements in childcare and parental leave.

Coalition and consensus making dynamics fundamentally changed over time. The social democrats, the liberals and the Christian democrats have lost their hegemonic control, and governing coalitions require four rather than two-party combinations, complicating coalition negotiations and reducing government stability. In addition, the social partners can no longer muster the strength they had in the past. Trade unions density has declined to 20%.

A novel feature of Dutch coalition politics concerns ad hoc budgetary agreements with variegated social partners and political parties from the so-called ‘constructive opposition’ parties. For example, the Rutte II government (liberals and social democrats, 2012-2017) did not have a majority in the senate and needed the support for intrusive reforms from the social liberals, the Christian progressives and the orthodox Calvinists. This right-of-centre support put considerable pressures on the social agenda of the social democrats, who needed dialogue with the social partners to maintain some level of legitimacy over a fair sharing of the burden of austerity. A series of social pacts avoided harsher retrenchment and further deregulation of dismissal legislation. However, the Rutte II administration was unable to agree on novel social security provision for independent workers without personnel, which today include over a million workers.

Under conditions of the financial and economic crisis, political fragmentation and social partnership erosion, the Dutch consensus machine continued to thrive to some extent in leveraging broad support over an intrusive reform agenda, while sustaining a somewhat ambiguous commitment to social investment.5.2 Belgium

In contrast to the Netherlands, Belgium remained ensnared in a vicious circle of ever higher social spending, higher taxation, labour shedding, and mounting public debt and deficits throughout the 1990s. Two institutional developments stood in the way of an overarching political consensus to break with the ‘welfare without work’ path and to take a social investment U-turn. First, pressure from rising community politics in the 1970s and 1980s led to the split of the party system along linguistic lines. Second, Belgium slowly moved from a unitary state to a federation of separate linguistic communities anchored in separate territorially defined Regions. Because the social security system was created as a centralized system based on the principle of national solidarity, Belgium’s internal division into two linguistic communities, characterized by very different economies historically, implied net social security transfers from one part of the country to the other, first from south to north and later from north to south. Strong national federations of labour unions consistently exerted their influence in defence of the status quo over the 1990s (Kuipers, 2006). Devolving welfare provision – for which the Flemish nationalists strongly advocated – long remained a political taboo for both the unions and the traditional parties, though most so on the French-speaking side (Marier, 2008, p. 85). Constant pressure from the Flemish side – especially in the wake of the electoral success of the New-Flemish Alliance (NVA) from 2003 onwards – put welfare devolution squarely on the table. Political negotiations and interest accommodation over the functional imperative of breaking the ‘welfare without work’ predicament gradually became entrapped within the more encompassing and politically salient issue of institutional reform.

Belgium thus became engaged in a fragmented, complex, conflict-ridden and lengthy welfare reform momentum, frustrating the adoption of social investment at the national level. The liberal-left government of 1999-2003 advanced the idea of an ‘Active Welfare State’, assertively spearheaded, especially by the SPA Health and Pensions Minister Frank Vandenbroucke, who was also instrumental in raising the social investment agenda to the European level under the Belgian presidency of the EU in the second half of 2001 (Vandenbroucke, 1999; 2002). However, activation measures adopted on the federal level were not accompanied by labour reforms to curtail employment protection. Disagreement between the social partners blocked these reforms. This set Belgian policymakers on an alternative course of a slow but progressive shift to a minimum protection model for all the unemployed in Belgium, with some expansion for outsider target groups, such as lone parents, the young and long-term unemployed, facing difficulties entering traditional employment-related social insurance (De Deken, 2011). However, guaranteed minimum income programmes remained insufficient to lift benefit claimants out of poverty (Kuipers, 2006, p. 187). Thus subsequent conservative-liberal governments discontinued this direction, and low activity remained the Achilles heel of the Belgian welfare state well into the first decade of the 21st century (Hemerijck & Marx, 2010).

Meanwhile, the Flemish Parliament adopted a decree for the creation of a Flemish care insurance in 1999 to ensure that the Communities and Regions could legitimately bring forward areas of welfare provision not yet covered under the national system (Dumont, 2015, p. 181). This widened the policy space of the federated entities – and especially the Flemish Community – to establish novel welfare provision for areas in which the traditional insurance-based national system was not active. Belgian welfare reform thus became immensely complex because, on the one hand, the integrity of the contribution-based system depended on its remaining undivided, while, on the other hand, Flemish demands for devolution were now backed up by the fact that many new social security initiatives could be established at the subnational level.

After the global financial crisis broke out, the Belgian federal government, with its record high public debt, was under enormous pressure to cut spending. Shortly thereafter, the NVA’s 2010 electoral victory threw Belgium into the deepest political crisis in decades, resolved only by the formation of a coalition between Christian democrats, socialists and liberals from both sides of the language barrier (Di Rupo government, 2010-2014) after a record 541-day formation period. Faced with the urgent imperative for welfare reform, this government reduced benefits and prolonged the waiting period for young unemployed to receive so-called insertion allowances in the national system. Eligibility and conditionality criteria were tightened for unemployment insurance in 2012, active labour market policy programmes were enforced with stricter rules for career breaks, and the idea was launched of a ‘community service obligation’ of two half-days a week for the long-term unemployed (Nicaise & Scheper, 2015).

Beyond the conscripted margins of fiscal retrenchment, other initiatives testified to a stronger commitment to social investment. Crucial was the so-called the ‘Sixth State Reform’, whereby the federated entities gained greater autonomy in social and labour market services, healthcare, housing, child benefits and parenting services, as of 2014. The Communities and Regions today give considerable weight to affordable and quality childcare and pre-primary education, to vocational training, and lifelong learning strategies, partially financed by the EU’s Youth Guarantee. Flanders has shifted to means-tested fees for childcare for disadvantaged families, while the Wallonia-Brussels Federation increased the provision of flexible childcare. However, the quasi-universal enrolment in pre-primary education hides low participation of specific target groups of children from disadvantaged families, children from ethnic or cultural minority groups and children with disabilities. Moreover, the biased nature in the uptake of leave benefits and the generosity of family benefits of long duration remains an obstacle to full-time labour market participation of women, especially mothers.

For the near future, the federated social security system, layered with fragmented two-tiered delivery of social services, is likely to restrict more proactive social investment diffusion across language regions. Moreover, ongoing regional devolution, with Flanders better able to progress in the direction of social investment, is likely to generate greater social disparities and deeper regional inequities (Nicaise & Schepers, 2015). Furthermore, while the leitmotiv of the Sixth State Reform was to shift Belgium’s centre of gravity from the federal state to the federated entities, instead of creating the political opportunities for more coherent social investment policy portfolios, the reforms provide for an extremely heterogeneous and fragmented devolution of welfare competences (Dumont, 2015, p. 175). -

6 Conclusion

If one zooms in on contemporary welfare state change, particularly when taking into account the shift towards the social investment paradigm, we conclude that the kinder, gentler hypothesis remains relevant. Consensus democracies stand out vis-á-vis the majoritarian systems in the extent to which their political institutions help to overcome the politically delicate intricacies of governing for the long term. We have theorized the institutional features that help to solve the problem of temporal commitment in democracy through processual mechanisms. Coalition practices that do not alternate governments but rotate coalition parties in government not only guarantee long-term reform continuity, but also distribute costs and burdens of reforms more evenly and fairly. If losers of reforms are identified, they are not ignored, but receive compensatory side-payments and/or longer phase-in periods, hence avoiding uncontrollable politicization of distributive conflict. This implies that even major reforms that break with historical legacies and potentially disappoint expectations do not meet with massive resistance. Moreover, in reform negotiations across a wide range of policy areas that take effect over long spans of time, political parties and social partner stakeholders can learn to trust each other, which in turn shapes a shared commitment to long-term goals, to gain knowledge and expertise on which reforms work to produce kinder, gentler democracies.

Able to rely on consensus articulation and decision-making mechanism, many continental welfare states, including Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, and, to a lesser extent, Belgium (for reasons explained previously), have been able to manage lengthy cumulative processes of welfare state transformation from a conservative Bismarckian social insurance model to significant social investment catch-up along three key dimensions. First, the overarching social policy objective has shifted from fighting unemployment to proactively promoting labour market participation. The objective is no longer to keep overt unemployment down by channelling (less productive) workers into social security programs but rather to maximize the rate of employment as the single most important policy goal. Second, with respect to labour regulation, most continental welfare states have moved towards greater acceptance of flexible labour markets, including non-standard employment such as fixed-term contracts and agency work. What is more, the normalization of ‘flexible work’ signalled a shift in attention from insiders (i.e. male breadwinners, their dependants and societal representatives) to women, low-skilled groups, the long-term unemployed and other youngsters. Third, perhaps most surprisingly, all continental welfare states have conclusively said ‘farewell to maternalism’ (Orloff, 2006) since 2000, not merely as a product of changing gender values, but more as a strategy to attract mothers into the workforce.

Let us conclude by formulating a somewhat paradoxical observation. Social investment reform seemed to have gained sway in continental welfare states precisely because retrenchment is difficult to push through when pre-committed compensatory benefits are vast. If intrusive benefit retrenchment is politically difficult then fiscally responsible governments are forced to explore alternatives and search for broad support for long-term social investment reforms. Such reforms must raise employment participation and labour productivity and at the same time should not rein in standing commitments too much. Only if the expensive yet popular welfare states also obtain a more sustainable fiscal footing can the type of broad social and political coalitions be forged that are necessary for long-term-oriented, transformative social investment reform. As we know from mainstream welfare state theory, once social investment programmes become institutionalized, they create their own clienteles and support, which in turn drive up quality standards for new welfare services, exactly like social security programmes did in the past. Organizing long-term policy consensus and political commitment for social investment becomes politically manageable, effectively making a politics of ‘affordable credit-claiming’ (Bonoli, 2012) quite practicable. References Bernardi, F. (2005). Public policies and low fertility: Rationales for public intervention and a diagnosis for the Spanish case. Journal of European Social Policy, 15(2), 123-138.

Birchfield, V. & Crepaz, M.M.L. (1998). The impact of constitutional structures and collective and competitive veto points on income inequality in industrialized democracies. European Journal of Political Research, 34(2), 175-200.

Bogaards, M. (2017). Comparative political regimes: Consensus and majoritarian democracy. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, 1-31. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.65.

Bonoli, G. (2007). Time matters: Postindustrialization, new social risks, and welfare state adaptation in advanced industrial democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 40(5), 495-520.

Bonoli, G. (2012). Blame avoidance and credit claiming revisited. In G. Bonoli & D. Natali (Eds.), The politics of the new welfare state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coppedge, M. (2018). Rethinking consensus vs. majoritarian democracy. Working Paper, Series 2018:78. Gothenburg: The Varieties of Democracy Institute.

Crepaz, M.M.L. (1998). Inclusion versus exclusion: Political institutions and welfare expenditures. Comparative Politics, 31(1), 61-80.

Croissant, A. & Schächter, T. (2009). Demokratiestrukturen in Asien-Befunde, Determinanten und Konsequenzen. ZPol Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft, 19(3), 387-419.

De Deken, J. (2011). Belgium: A precursor muddling through? In J. Clasen & D. Clegg (Eds.), Regulating the risks of unemployment (pp. 100-120). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dumont, D. (2015). La sécurite sociale et la Sixième Réforme de l’État: retroactes et mise en perspective générale. Revue belge de sécurité sociale, (2), 175-226.

Esping-Andersen, G. (Ed.) (1996a). Welfare states in transition: National adaptations in global economies. London: Sage.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1996b). Welfare states without work: the impasse of labour shedding and familialism in continental European social policy. In G. Esping-Andersen (Ed.), Welfare states in transition: National adaptations in global economies (pp. 66-87). London: Sage.

Fortin, J. (2008). Patterns of democracy? Zeitschrift für vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, 2(2), 198-220.

Giuliani, M. (2016). Patterns of democracy reconsidered: The ambiguous relationship between corporatism and consensualism. European Journal of Political Research, 55(1), 22-42.

Hemerijck, A. (2013). Changing welfare states. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hemerijck, A. (Ed.) (2017). The uses of social investment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hemerijck, A. & Eichhorst, W. (2010). Whatever happened to the Bismarckian welfare state? From labor shedding to employment-friendly reforms. In B. Palier (Ed.), A long goodbye to Bismarck? The politics of welfare reforms in continental Europe (pp. 301-332). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Hemerijck, A. & Marx, I (2010) Continental Welfare at a Crossroads: The choice between Activation and Minimum Income Protection in Belgium and the Netherlands. In B. Palier (Ed.), A long goodbye to Bismarck? The politics of welfare reforms in continental Europe (pp. 129-155).

Hemerijck, A. & Ronchi, S. (forthcoming). European welfare states’ detour(s) to social investment. In E. Ferlie & E. Ongaro (Eds.), The Oxford international handbook of public administration for social policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Houwing, H. (2010). A Dutch approach to flexicurity? Negotiated change in the organization of temporary work. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Iversen, T. & Soskice, D. (2006). Electoral institutions and the politics of coalitions: Why some democracies redistribute more than others. American Political Science Review, 100(2), 165-181.

Jacobs, A.M. (2011). Governing for the long term: Democracy and the politics of investment. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Jacobs, A.M. (2016). Policy making for the long term in advanced democracies. Annual Review of Political Science, 19, 433-454.

Jacobs, A.M. & Matthews, J.S. (2017). Policy attitudes in institutional context: Rules, uncertainty, and the mass politics of public investment. American Journal of Political Science, 61(1), 194-207.

Lijphart, A. (1999; second edition 2012). Patterns of democracy: Government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Lindert, P.H. (2004). Growing public: Volume 1, the story: Social spending and economic growth since the eighteenth century (Vol. 1). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Kuipers, S. (2006). The crisis imperative: Crisis rhetoric and welfare state reform in Belgium and the Netherlands in the early 1990s. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Marier, P. (2008). Pension politics: Consensus and social conflict in ageing societies. New York: Routledge.

McCarty, N. & Pontusson, J. (2009). The political economy of inequality and redistribution. In W. Salverda, B. Nolan & T. M. Smeeding (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of economic inequality (pp. 665-692). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Meltzer, A. H. & Richard, S. F. (1981). A rational theory of the size of government. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 914-927.

Nicaise, I. & Schepers, W. (2015). ESPN thematic report on social investment Belgium, European Network Social Policy Network (ESPN), Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission.

Orloff, A. (2006). From maternalism to “employment for all”: State policies to promote women’s employment across the affluent democracies. In J. Levy (Ed.), The state after statism: New state activities in the age of liberalization. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Palier, B. (Ed.). (2010). A long goodbye to Bismarck? The politics of welfare reforms in continental Europe. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Palier, B. & Thelen, K. (2010). Institutionalizing dualism: Complementarities and change in France and Germany. Politics & Society, 38(1), 119-148.

Pierson, P. (1996). The new politics of the welfare state. World Politics, 48(2), 143-179.

Pierson, P. (2004). Politics in time: History, institutions, and social analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rehm, P. (2011). Social policy by popular demand. World Politics, 63(2), 271-299.

Roller, E. (2005). The performance of democracies: Political institutions and public policies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Streeck, W. & Thelen, K.A. (Eds.). (2005). Beyond continuity: Institutional change in advanced political economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tavits, M. (2004). The size of government in majoritarian and consensus democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 37(3), 340-359.

Van Kersbergen, K. (1995). Social capitalism: A study of Christian democracy and the welfare state. London: Routledge.

Van Kersbergen, K. & Hemerijck, A. (2012). Two decades of change in Europe: The emergence of the social investment state. Journal of Social Policy, 41(3), 475-492.

Van Kersbergen, K. & Manow, P. (Eds). (2009). Religion, class coalitions, and welfare states, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Vandenbroucke, F. (1999). The active welfare state: A European ambition. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Den Uyl Lecture.

Vandenbroucke, F. (2002). Foreword. In G. Esping-Andersen, A. Hemerijck, D. Gallie & J. Myles (Eds.), Why we need a new welfare state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vatter, A. (2009). Lijphart expanded: Three dimensions of democracy in advanced OECD countries? European Political Science Review, 1(1), 125-154.

Vatter, A. & Bernauer, J. (2009). The missing dimension of democracy: Institutional patterns in 25 EU Member States between 1997 and 2006. European Union Politics, 10(3), 335-359.

Visser, J. & Hemerijck, A. (1997). A Dutch miracle: Job growth, welfare reform and corporatism in the Netherlands. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.

Noten

-

1 We thank two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and Chris Vermorken and Stefano Ronchi for their research assistance.