Sculpting the Provision of Student Support for Law Students to Enhance Inclusivity: Complications and Challenges

-

1 Introduction

In the ever-evolving landscape of legal education, the pursuit of inclusivity has emerged as a central pillar of academic excellence. As the legal profession strives to reflect the diverse societies it serves, law schools must play a pivotal role in fostering an inclusive environment where all can thrive. The pursuit of inclusivity in higher education is closely related to the provision of student support as the means to help ensure that students from all backgrounds are supported to achieve their fullest potential.1x G. Layer, ‘Developing Inclusivity’, 21 International Journal of Lifelong Learning 3, at 4 (2002).

The importance of fostering student well-being in higher education settings has been well-emphasised,2x Cf. S. Coyle, ‘“Make glorious mistakes!” Fostering Growth and Wellbeing in HE Transition’, 56(1) The Law Teacher 37, at 40 (2022); J. Duffy, R. Field, K. Pappalardo, A. Huggins & W. James, ‘The “I Belong in the LLB Program” Animating and Promoting Law Student Wellbeing’, 41 Alternative Law Journal 1, at 52 (2016); N. Duncan, R. Field & C. Strevens, ‘Ethical Imperatives for Legal Educators to Promote Law Student Wellbeing’, 23 Legal Ethics 1-2 at 65 f (2020); H.-W. Rückert, ‘Students’ Mental Health and Psychological Counselling in Europe’, 3 Mental Health and Prevention at 38-39 (2015). particularly in recent years driven in part by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.3x A. Parfitt, S. Read & T. Bush, ‘Can Compassion Provide a Lifeline for Navigating Coronavirus (COVID-19) in Higher Education?’ 39 Pastoral Care in Education 3, at 187 (2021) providing that ‘the COVID-19 pandemic has apparently brought to the fore the vulnerabilities of all human bodies.’ Cf. J. Neves and R. Hewitt, ‘Student Academic Experience Survey 2021’, Advance HE, at 50. Available at: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/SAES_2021_FINAL.pdf (last visited 20 March 2024); R. O’Connor, ‘Supporting Students to Better Support Themselves through Reverse Mentoring: The Power of Positive Staff/Student Relationships and Authentic Conversations in the Law School’, 57 The Law Teacher 3, at 254 (2023). Moreover, law students have been continuously identified internationally as being particularly vulnerable to low levels of well-being.4x Cf. Coyle, above n. 2; Duffy et al., above n. 2, at 52-53; Duncan et al., above n. 2, at 68; L.D. Eron and R.S. Redmount, ‘The Effect of Legal Education on Attitudes’, 9 Journal of Legal Education 4, at 435 (1957) identified law students as obtaining significantly higher anxiety scores in particular in comparison to medical students; G. Ferris, ‘Law-Students Wellbeing and Vulnerability’, 56 The Law Teacher 1, at 7 (2022); N. Kelk et al., ‘Courting the Blues: Attitudes towards Depression in Australian Law Students and Lawyers’, Brain and Mind Research Institute, University of Sydney, at 1 (2009); E.G. Lewis and J.M. Cardwell, ‘A Comparative Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing among UK Students on Professional Degree Programmes’, 43 Journal of Further and Higher Education 9, at 1229-1231 (2019); R.A. McKinney, ‘Depression and Anxiety in Law Students: Are We Part of the Problem and Can We Be Part of the Solution?’ 8 The Journal of the Legal Writing Institute, at 229 f (2002); K.M. Sheldon and L.S. Krieger, ‘Does Legal Education Have Undermining Effects on Law Students? Evaluating Changes in Motivation, Values and Well-Being’, 22 Behavioural Sciences and the Law, at 275 (2004); N. Skead and S.L. Rogers, ‘Stress, Anxiety and Depression in Law Students: How Student Behaviours Affect Student Wellbeing’, 40 Monash University Law Review 2, at 572 (2014); M. Townes-O’Brien, S. Tang & K. Hall, ‘Changing our Thinking: Empirical Research on Law Student Wellbeing, Thinking Styles and the Law Curriculum’, 21 Legal Education Review 2, at 150 and 159-60 (2011). Against this backdrop, the impetus is on law schools to ensure that they are adequately promoting student well-being alongside their traditional curricular offerings so as to be truly inclusive.5x Cf. Duffy et al., above n. 2, at 52; Skead and Rogers, above n. 4, at 567. Other initiatives include the integration of information on well-being awareness into law programmes specifically: cf. L. Crowley-Cyr, ‘Promoting Mental Wellbeing of Law Students: Breaking-Down Stigma and Building —Bridges with Support Services in the Online Learning Environment’, 14 QUT Law Review 1, at 132 (2014).

This article will explore the role that student support systems can play in achieving inclusivity. In practice, student support services frequently keep academic and pastoral roles entirely separate. We argue that the provision of academic support and pastoral care for law students should be deemed in practice as intrinsically holistic to fully realise inclusivity. In essence, this article will contend that the remit of the legal academic needs to pivot from being purely concerned with academic support to recognise the broader signposting that academic advisors often engage in to ensure students obtain the professional pastoral support they require.

In developing this argument, this article begins by depicting the UK higher educational context within which it finds itself. It then explores the blurred line between academic support and pastoral care before turning to the design of an inclusive student support system in which a taxonomy on the provision of student support is created to analyse the interconnection between student academic support and pastoral care needs. This taxonomy considers a range of relevant factors in the provision of student support from the factors that may trigger student support in the first instance to the types of support available and the providers of support. The role of academics in providing holistic and inclusive student support will then be explored before the article presents its conclusions. -

2 UK Legal Education Context in England and Wales

It is necessary to start by outlining the legal education landscape in England and Wales to aid your understanding of the authors’ context throughout this article. There are approximately 120 providers of legal education in England and Wales. The most common undergraduate degree is the standard full-time three-year LLB degree. The majority of students in England and Wales will start their degree straight from secondary education, which makes them typically around 18 years of age. There are a growing number of part-time and distance learning programmes. Those students who wish to practise law must undertake additional professional examinations, which are also open to non-law graduates, and these examinations are completed in different stages after students have completed their undergraduate degree. The legal profession in England and Wales is split between solicitors who undertake a client-facing role and barristers who undertake an advocacy court-facing role. Those students intending to practise will select to proceed on to further education and qualify as a solicitor or a barrister.

The authors are all based in the Northwest of England at Lancaster University, and our roles involve both lecturing in different fields of law and in providing students with academic and pastoral support. Lancaster University is currently ranked 10th overall and its Law School is ranked 11th in the UK.6x The Guardian, ‘The Guardian University Guide 2024 – The Rankings’ (available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/universityguide (last visited 9 April 2024). We have a tiered system of support for our students. We have academic advisors who are students’ regular points of contact for their whole degree, and these advisors are supported by year tutors who in turn support students who experience significant challenges during their degree. There is also a senior personal tutor who administrates the student support system by supporting both academic advisors and year tutors in their roles. These roles are undertaken by academic colleagues, which means a significant part of this role is signposting students to the different parts of the university that can help a student with their challenges.

We acknowledge our focus is written from a particular UK higher education-specific context, and we recognise that our current context is a single UK higher education institution. This is a limitation, but we draw upon a range of domestic and international literature to support the development of our ideas and conclusions. We view this article as the starting point for readers to reflect on their own teaching practice based on the issues we raise from our collective experience. -

3 The Blurred Line of Academic and Pastoral Care Roles

This article will now consider the traditional distinction between the separation of academic and pastoral care. In particular, it will examine the rationale supporting this distinction and show that whilst it may have considerable value in theory, it now requires a re-evaluation considering students’ practical needs and the changing academic landscape. The fast-changing nature of academic studies was recently demonstrated by the global coronavirus pandemic, which highlighted the pressing need for robust student support systems in higher education.7x Cf. Neves and Hewitt, above n. 3. Furthermore, if higher education institutions are serious about inclusivity, they need to continually re-evaluate how student support systems work to ensure that they are helping all students to achieve their full potential.

It is worth noting at the outset that student support can be provided on an individual basis, it can target specific groups of students8x For example, students identified as ‘at risk’: cf. S. McChlery and J. Wilke, ‘Pastoral Support to Undergraduates in Higher Education’, 8 International Journal of Management Education, at 24 (2009); For students with a disability, cf. A. MacLeod and S. Green, ‘Beyond the Books: Case Study of a Collaborative and Holistic Support Model for University Students with Asperger Syndrome’, 34 Studies in Higher Education, at 631 (2009). and/or it may be open to all students.9x D.M. Velliaris (ed.), Academic Language and Learning Support Services in Higher Education, Advances in Higher Education and Professional Development, at xiii (2019). Moreover, student support can be provided by various services both internal and external to higher education institutions.10x Cf. C. Walsh, C. Larsen & D. Parry, ‘Academic Tutors at the Frontline of Student Support in a Cohort of Students Succeeding in Higher Education’, 35 Educational Studies, at 411 (2009) listing the following student support services: academic tutor, student union, counselling, student finance, personal tutor, academic progression advisors, careers service, chaplaincy, student discipline service, student health service and so on. -

4 Glossary of Terms

The use of terminology to label student support roles is a salient issue given that many higher education institutions adopt a variety of terms to capture the nature of these caring roles.11x M. Calvert, ‘From “Pastoral Care” to “Care”: Meanings and Practices’, 27 Pastoral Care in Education, at 269 (2009). The name given to roles is important, as it sets an expectation for the student as to what help they can expect to obtain from the person exercising that role. To understand student support, it is necessary to introduce the key terms, which will be adopted throughout this article, and elaborate upon them. The justifications for these definitions are explained in the subsections that follow below.

Student Support Services: an umbrella term denoting an array of formal institutional mechanisms dedicated to students’ advancement and development, encompassing support forms falling under both academic support and pastoral care but which can also include broader forms of support, for example, transitional support when moving from secondary- to tertiary-level education.

Academic Support: provision of educational guidance and assistance, for example, with the progressive development of digital literacy skills, professional research skills, communication and legal writing skills and so on relative to the particularities of each student and accounting for the diversity of student cohorts.

Pastoral Care: provision of well-being support that extends beyond the ambit of academic support (e.g. counselling, exceptional circumstances, extensions, provision of understanding and compassion relative to the factors affecting students).

Academic Advisor: an academic member of staff acting as a student’s personal tutor to stimulate students’ educational development and promote their progress and retention, usually by meeting with their advisees individually and periodically throughout the academic year.

Year Tutor or Level Tutor: an academic member of staff providing a point of contact in relation to pastoral care within the department, in particular signposting to other forms of institutional level support.12x Cf. J. Earwaker, Helping and Supporting Students, Rethinking the Issues (1992), at 45.

-

5 Distinguishing Academic and Pastoral Care

5.1 Academic Support

Buckley traces the origins of separate academic and pastoral roles to a belief in education that student learning should be separated between students who need to learn and students who need to be cared for.13x J. Buckley, ‘The Case of Learning: Some Implications for School Organisation’ in R. Best, C. Jarvis & P. Ribbins (eds.), Perspectives on Pastoral Care (1980), at 183. Furthermore, Buckley explains that not only are students divided but academics were also traditionally divided between academics who teach their students to learn and those academics who provide care for students.14x Ibid. This understanding of education helps at least in part to appreciate the origins of the division between pastoral and academic roles. Other more practical reasons may exist to help to explain this division, such as the need to ensure that those undertaking a pastoral caring role have sufficient professional qualifications to enable more tailored advice to students on matters related to personal well-being.

A natural starting point is to consider the validity of the division between these two roles: academic care and pastoral care. The term ‘academic support’ involves considering two specific terms that have a close relationship to each other in the provision of student support and provide a means to understand what might constitute academic care: ‘academic support’ and ‘academic advisor’. Academic support is traditionally understood as involving the provision of some level of assistance and guidance to any student who may ‘struggle’ during their studies.15x Ibid. See also: K. Knaplund and R. Sander, ‘The Art and Science of Academic Support’, 45 Journal of Education 157, at 160 (1995). It is furthermore common that academic support is mainly provided within law departments, through programmes developed or supervised by academic colleagues.16x T.D. Peterson and E.W. Peterson, ‘Stemming the Tide of Law Student Depression: What Law Schools Need to Learn from the Science of Positive Psychology’, 9 Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law and Ethics, at 361 (2009). Frequently, academic support is primarily concerned with developing academic skills necessary for student progression. On most law degrees, many students will engage with study skills formally as part of their course, typically through an ‘introduction to law’ module as well as an extended introduction to skills over each year of their studies.17x Cf. A.G. Todd, ‘Academic Support Programs: Effective Support through a Systemic Approach’, 38 Gonzaga Law Review, at 187 (2002). This approach has tended to create a skills focus in the provision of student support, which is perhaps expected given the responsibility for this part of the student support offering falls to individual law departments. However, many law schools also offer additional support services, such as writing support clinics, as well as colleagues specifically aimed at supporting students through their learning development. The formal provision of skills modules tends to help with the general development of academic skills, but the focus in this article is on the extra support systems that sit outside formal modules to understand how they may form part of a student support ecosystem supporting and promoting inclusivity.

Traditionally, access to these additional academic support services has tended to be for those students identified as struggling during their studies, with academic colleagues often referring students on specific skills that are identified as needing improvement.18x Cf. P.T. Wangerin, ‘Law School Academic Support Programs’, 40 Hastings Law Journal, at 773 (1989). This referral is more common after a weak performance in an assessment as the basis to develop any skill gaps. The process of referring students to academic support after a weak assessment performance may result in stereotyping some weaker students and can result in these support services being viewed as only for ‘struggling’ students. Furthermore, and more broadly, it undermines the solidification of inclusivity as a core bastion of the higher education framework. In our view, this narrow understanding of academic support is also limited and fails to fully appreciate the benefit of all students accessing these academic support services on a regularised basis. Academic support can be much broader by helping students to improve their academic skills by empowering them to become capable independent learners so that they can attain all of the learning outcomes of their programme of study.19x K.S. Knaplund and R.H. Sander, ‘The Art and Science of Academic Support’, 45 Journal of Legal Education 157, at 161 (1995). See also: S. Atkinson, Rethinking Personal Tutoring Systems: The Need to Build on a Foundation of Epistemological Beliefs (2014). As a result, any student support system will need to consider the role that academic support fulfils. We will return to this issue later in the article, but for now we define academic support broadly to include the provision of a range of support mechanisms and guidance to help empower students to become independent learners. In our own law school’s context, academic support exists in a variety of strands, such as via academic advisors, a legal writing support clinic providing tailored skills support, in addition to broader individual support from the faculty’s learning developer.

The use of the term ‘academic advisor’ indicates a more formal relationship between an academic and a student in which the academic’s role is predominately focused on assisting students to realise their educational goals. Academic advisors commonly meet with their advisees at structured points throughout the year, with the objective of catching up with a student and assessing their progress to ensure they remain on track towards meeting their objectives. At university, this will commonly involve providing support to the student to ensure they obtain their degree as the means to find a pathway to employment.5.2 Pastoral Care

The use of the term ‘pastoral care’ has been in existence since at least the 1970s, but its precise scope has tended to be vague.20x R. Best, C. Jarvis & P. Ribbins, ‘Pastoral Care: Concept and process’, 25 British Journal of Education Studies, at 125 (1977). See also: P. Ghengheshl, ‘Personal Tutoring from the Perspectives of Tutors and Tutees’, 42 Journal of Further and Higher Education, at 570 (2018). Hughes notes that pastoral care was first used in formal academic circles in 1974.21x P. Hughes, ‘Pastoral Care: The Historical Context’ in R. Best, C. Jarvis & P. Ribbins (eds.), Perspectives on Pastoral Care, at 28 (1980). The term ‘pastoral’ usually has undertones of religious care or shepherding others to a better place.22x M. Maryland, Pastoral Care, at 11 (1974). ‘Pastoral care’ might be helpful to indicate the caring nature of a role or a scheme assigned with providing care, but often pastoral care remains too vague and unclear as a term and concept without a precise scope in higher education.23x For example, A. Clemett and J. Pearce, The Evaluation of Pastoral Care, at 43 (1986). See also: C. Walker, ‘Wellbeing in Higher Education: A Student Perspective’, 40 Pastoral Care in Education 3, at 310 (2022). Furthermore, the scope of academic support may differ greatly from institution to institution depending on the support structures adopted. Dooley suggests that ‘pastoral care’ is closely related to nurturing and guiding others.24x S. Dooley, ‘The Relationship between the Concepts of Pastoral Care and Authority’, 7(3) Journal of Moral Education 182, p. 185 (1978).

Student support provision concerned with pastoral care is often located outside of law departments and usually falls under the supervision of professional services colleagues who may, where applicable, hold professional qualifications in a dynamic array of areas related to student well-being. This may include professional counsellors, as well as colleagues providing support with, for example, accommodation and employment or catering to the individual needs of students with disabilities.

A concern identified by Best et al. is the lack of clarity in the relationship between ‘pastoral care’ and other similar type of activities such as ‘guidance’, or even ‘counselling’.25x Best, Jarvis & Ribbins, above n. 20, at 129. This may become more problematic when considering the labels ‘academic support’ or ‘academic advisor’ and their relationship with pastoral support. The significance of this vagueness is that those academic colleagues performing the caring roles and the students accessing care provision may have a degree of confusion around what these terms mean. This confusion, or even potential confusion, may impact the desired aim of student support as a means to help students through their academic pathway, as well as maintaining a positive student experience at university.26x Cf. Earwaker, above n. 12, at 45 providing that professional services staff may have a clearer picture as to the nature of support to provide than academic staff. Also see E. Hellwig, ‘Pastoral Care for the 1990s and beyond: A visitor viewpoint’, 7 Pastoral Care in Education, at 8 (1989) highlighting the problem with the lack of clarity on the nature of student support provided, the implementation of it, the development of any roles assigned with the provision of student support, and the type of support provided, which undermines policy decision-making in education. -

6 Practical Realities in Student Support

This discussion shows that understanding the nature of support roles has a fundamental impact on how these roles work in practice. The distinction between academic support and pastoral care can serve as a valuable analytical tool to appreciate theoretically the nature of each support strand, as well as its scope and the development of good practice to enhance its provision. It can also assist with having a clear dividing line between the role of the academic and the role fulfilled by professional well-being colleagues. However, in our experience, academic colleagues can sometimes be placed in circumstances that blur the dividing line between pure academic and pastoral issues. In these circumstances, the academic advisor’s role is often about providing compassion and empathy to their advisees and then signposting them to the appropriate professional well-being service. We are not suggesting that academic colleagues should be more involved in the direct provision of professional well-being services; rather, we are advocating that our student support systems (in their design and delivery) should be more mindful of the reality in practice and strive to promote positive student well-being as an integral component of the higher educational framework.27x Cf. Walker, above n. 23, at 317-18; Crowley-Cyr, above n. 5, at 132. This may require a rethink on the provision of well-being, moving it closer to the student in their department, such as within the law department/school itself28x Cf. D. De Coninck, K. Matthijs & P. Luyten, ‘Subjective Well-being among First-Year University Students: A Two-wave Prospective Study in Flanders, Belgium’, 10 Student Success 1, at 42 (2019) recommending that student counsellors are made available within faculties. Also see Walker, above n. 23, at 313-14 on pastoral support teams inter alia existing within departments; see M.P. Cameron and S. Siameja, ‘An Experimental Evaluation of a Proactive Pastoral Care Initiative Within an Introductory University Course’, 49 Applied Economics 18, 1809 f (2017) advocating a ‘proactive pastoral care initiative’ in which academic staff provide tailored support to students identified at higher risk of non-completion. or even within curriculum design.29x Cf. Crowley-Cyr, above n. 5, at 132; A. Macduff and V. Holmes, ‘Harnessing the Winds of Change’, 56 The Law Teacher 1, at 133 (2022); C. Strevens and C. Wilson, ‘Law Student Wellbeing in the UK: A Call for Curriculum Intervention’, 11 Journal of Commonwealth Law and Higher Education 1, at 51 (2016). In doing so, this would foster students’ sense of community within their department, which is intrinsic to the notion of inclusivity itself.30x Cf. T. Booth and M. Ainscow, Index for Inclusion: Developing Learning and Participation in Schools, Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education (2002), at 3. Also see Townes-O’Brien, Tang and Hallabove n. 4, at 176 providing for improved relationships with peers and teachers as creating a sense of community. Additionally, this recognition would require regular reviews of training required for academic colleagues to ensure they are supported in dealing with the many challenging issues frequently experienced when fulfilling academic advisor roles. This may include, for example, mental health first-aider training.31x M. Appleby and J. Burke, ‘Promoting Law Student Mental Health Literacy and Wellbeing: A Case Study from the College of Law, Australia’, 20 International Journal of Clinical Legal Education 1, at 492 (2014) advocating MHFA training for all legal academics and those in student-facing roles.

The challenge with pastoral care existing as an entirely external structure is that this can create a barrier to students accessing well-being support. This barrier can emerge from a fear of the unknown about the types of services provided by professional colleagues in well-being, a stereotype or stigma,32x Cf. Crowley-Cyr, above n. 5, at 133-35. as well as a process to access such services that can be complicated and difficult to navigate for students facing challenges during their studies.33x T.A. Laws and B.A. Fielder, ‘Universities’ Expectations of Pastoral Care: Trends, Stressors, Resource Gaps and Support Needs for Teaching Staff’, 32 Nurse Education Today, at 799 (2012). Usually, the responsibility for the design and delivery of these services is assigned to institutional counselling and well-being services. It is often the case that the challenges students face raise both pastoral and academic issues, which means that pastoral care alone cannot function in a vacuum.34x Cf. Pastoral care definition in Section 5.2. The provision of pastoral care may relate, for example, to the provision of advice about law students’ future career progression and employability.35x C. Smith and J. Allen, ‘Essential Functions of Academic Advising: What Students Want and Get’, 26 NACADA Journal 56, at 60 (2006). It may furthermore connote the provision of opportunities for financially struggling students to either develop their life or vocational skills further or assist them in undertaking some form of employment during their studies to supplement their income.

It is commendable that student support is increasingly regarded as a key component of higher education;36x Cf. Earwaker, above n. 12, at 132. however, an important concern relates to how academic and pastoral support can operate holistically and inclusively from the student perspective. Like every other student in higher education, law students come to law departments with a range of life experiences and different skills and capacities to attain the learning outcomes and objectives of a law degree.37x K. Galloway and R. Bradshaw, ‘Responding to Changed Parameters of the Law Student: A Reflection on Pastoral Care in the Law School’, 3 Journal of the Australasian Law Teachers Association 101, at 108 (2010).

The compartmentalisation of student support needs during the design and delivery of academic and pastoral care offerings would only make sense if law students’ support needs possessed some form of homogeneity when it comes to identifying their nature and addressability. Such homogeneity may exist to some extent, at least when it comes to providing academic advice on enhancing vocational literacy skills, such as how to read and understand case law. However, pastoral care issues are unique to student circumstances and are reflective of the student themself. Any student support system providing academic and pastoral support needs to be sufficiently nimble so as to ensure that students are supported sufficiently during their studies. This flexibility requires recognition of the thin and blurred line between academic and pastoral issues.38x Ibid., at 107-10.

This complexity can be addressed by constructing student support services that recognise that the dividing line between academic support and pastoral care may be ill-equipped to embody or address the dynamic nature of students’ support needs. A variety of strategies to provide academic support and pastoral care in an integrative manner which is cognisant of these varying dynamics is therefore required. Identifying this need requires considerable deliberation about the ways academic support and pastoral care should operate in practice. In addition to this, the identification of the ways academic support and pastoral care can be provided extends to discussing the role that universities should play in the lives of those who attend them, including both colleagues and students.39x This inherently relates to the current structures and policies implemented in law schools and higher education institutions in recent years. See on this, S. Brown, ‘Bringing about Positive Change in the Higher Education Student Experience: A Case Study’, 19 Quality Assurance in Education, at 195 (2011); D. Morrison and J. Guth, ‘Rethinking the Neoliberal University: Embracing Vulnerability in English Law Schools?’ 55 The Law Teacher, at 42 (2021). -

7 Designing an Inclusive Student Support System

7.1 Theoretical Underpinnings

Biesta explains that the ‘purpose’ of education comprises ‘a multidimensional question, because education tends to function in relation to a number of domains … qualification, socialisation and subjectivation’.40x G. Biesta, ‘What Is Education for? On Good Education, Teacher Judgement, and Educational Professionalism’, 50 European Journal of Education 75, at 75 (2005). Qualification is concerned with knowledge transmission and attainment; socialisation is concerned with students becoming part of social, cultural, religious and political traditions and practices in helping to establish their identity.41x Ibid. Subjectivisation concerns the impact of education on the individual, which can be labelled the human dimension.42x Ibid. This understanding of the purpose of education reveals that whilst students may enrol onto a higher education programme of study to gain knowledge to further their career plans and prospects, there are also at least two other domains related to the development of the student ‘self’. As a result, higher education and its support structures should not only ensure that students learn through gaining knowledge but should also provide the means to support students to realise their own personal learning development.

An effective student support system must be able to take into account students’ interrelated and interdependent needs in relation to academic support and pastoral care and dynamically respond to them in a coordinated, integrative and inclusive manner.43x Earwaker, above n. 12, at 132. Several roles and schemes must be considered, designed and developed, which includes identifying the specific attributes and roles that each one should play in the provision of academic support and pastoral care.7.2 Taxonomy

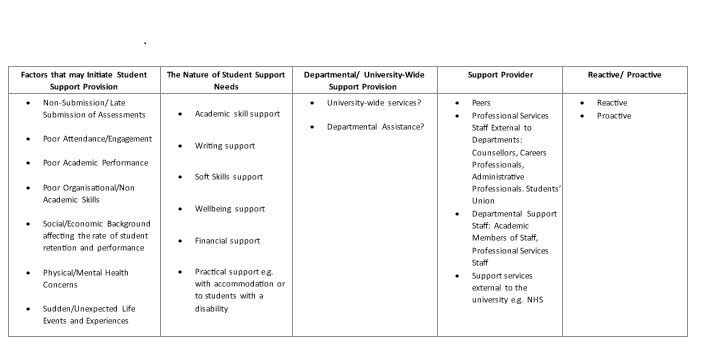

To assist in the consideration and practical design and development of schemes and roles that effectively provide academic support and pastoral care in an integrative manner, Figure 1 presents a taxonomy that articulates the ways in which student support can operate to achieve this. This taxonomy is informed by the varying dynamics that may affect students’ support needs and the factors or occurrences which may initiate student support provision. At the same time, the taxonomy seeks to consider how support is to be provided relative to the academic support and pastoral care needs law students may have, which may extend to considering the level at which academic support and pastoral care are provided, the role or scheme that needs to be developed and is tasked with providing it, and the timing of such support being made available.

A Taxonomy for the Operationalisation of the provision of student support

The taxonomy’s first dimension conceptualises the likely factors that may lead a law student or a support provider to initiate the provision of student support. Several examples of such factors may revolve around law students’ academic performance, which may relate to a student’s assessment submission or examinations. Poor attendance or engagement or a sudden drop in students’ academic performance or retention may also be considered as a trigger initiating the provision of student support. Beyond academic matters, several factors may relate to students’ life experiences and events. External factors, for example, can preclude students from engaging with their studies or performing to the standard required to make the most of their degree. Physical or mental health issues occurring before or during the students’ studies may furthermore be an important factor to consider, alongside sudden or unexpected events that may lead a student to require support during their studies, such as a bereavement or a student experiencing some form of physical harm. It is also worth mentioning that the aforementioned factors triggering support may arise simultaneously.

The taxonomy’s second dimension concerns determining the type of student support needed. The examples provided here are not intended to be exhaustive but merely indicative of the range of support higher education institutions and law school departments provide to students.

The taxonomy’s third dimension considers whether the support required should be accessed specifically at a departmental level or whether it should be facilitated as part of the wider services and support the university provides to all students institutionally. It is our view that one way to make student support more inclusive to is to consider how these professional well-being roles can become more integrated into departments in the same way as other existing departmental support roles such as academic skills and learning developers. This would require additional resources being allocated to departments to allow the recruitment of professionally trained well-being colleagues. This would allow academic colleagues tasked with support roles to signpost to well-being colleagues within their own departments, thus bolstering efficiency as well as students’ sense of community44x Cf. Skead and Rogers, above n. 4, at 585 recognising the link between student well-being and a student’s sense of belonging. within their academic departments.45x Cf. De Coninck, Matthijs & Luyten, above n. 28; Walker, above n. 23, at 313-14. This would provide one way to normalise accessing well-being support and in turn could become a way to destigmatise accessing well-being support. The challenge for universities is the financial consequences of such a move given that various programmes will have shifting enrolment numbers over different years, and this can create significant uncertainty around the year-on-year demand in individual departments. One way that this may be managed and mitigated would be to move professional well-being roles within individual faculties where professional colleagues could be faculty-wide to create a way to ensure the sustainability of pivoting well-being support within departments.46x Cf. De Coninck, Matthijs & Luyten, above n. 28.

At minimum, it is important that this part of the process can identify the level of support that is appropriate to support a student in need, as this will shape the design and development of departmental schemes. It can furthermore assist in the creation of prudent streams of communication between university-level support and departmental roles and schemes in a much more integrative manner.

The taxonomy’s fourth dimension also acknowledges that several actors can undertake a supporting role, whether at the departmental level or at the university level. The taxonomy first identifies that students’ peers can assist as a source of support. Peer support groups in law schools that are supervised by academic colleagues have been noted in the literature over the years, especially with regard to academic support concerned with learning and writing skills.47x See, for example, J. Cahill, J. Bowyer & S. Murray, ‘An Exploration of Undergraduate Students’ Views on the Effectiveness of Academic and Pastoral Support’, 56 Educational Research, at 406-7 (2014); D. Fitzsimmons, S. Kozlina & P.E. Vines, ‘Optimising the First Year Experience in Law: The Law Peer Tutor Program at the University of New South Wales’, UNSW Law Research Paper No. 2007-7 (2007); cf. Wangerin, above n. 18, at 783. Peer support groups can also be prevalent in pastoral care provision.48x Cf. Townes-O’Brien, Tang & Hall, above n. 4, at 174. Also see Australian Law Students’ Association, Depression in Australian Law Schools: A Handbook for Law Students and Law Student Societies, 18-20. Available at: https://law.uq.edu.au/files/32504/alsa-depression-handbook.pdf (last visited 19 March 2024). An example may be found in the provision of peer assistance to students who may struggle with their studies or even their ability to cope with social interactions. Lancaster University’s Buddy Programme can be seen as a programme developed to this end.49x See: https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/graduate-college/information-for-students/the-buddy-programme/ (last visited 9 April 2024). This is also replicated at other universities, cf: N. Quinn, A. Wilson, G. MacIntyre & T. Tinklin, ‘People Look at You Differently’: Students’ Experience of Mental Health Support within Higher Education’, 37 British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, at 414 (2009). The programme aims to cultivate the creation of connections between current and new students to provide social support on campus and with studies. The harnessing of peer group support is not aimed at replacing established professional support available in departments but focuses rather on fostering students’ sense of community as law students per se.

The taxonomy’s fifth dimension considers the timing of support. In this regard, it is necessary to consider whether support should respond to students’ support needs reactively after a specific event has occurred or whether it should proactively cultivate the environment required for dynamic student support provision before specific support needs arise. We advocate the latter approach in the departmental context.50x Cf. Cameron and Siameja, above n. 28; Ferris, above n. 4, at 17. -

8 The Importance of Academic Colleagues in the Provision of Holistic and Inclusive Student Support

The central importance of well-being support has underscored the salience of a student’s first point of contact for all support needs being within their academic department, that is, in the law school itself. The traditional and well-established distinction between academic support and pastoral care fails to recognise that student support needs are not binary in nature but are in fact becoming increasingly complex, comprehensive and acute, accentuated recently during the COVID-19 pandemic,51x Neves and Hewitt, above n. 3; O’Connor, above n. 3, at 253-4. This also includes financial support needs: cf. Gov.UK Press Release, ‘Government Announces £50 Million to Support Students Impacted by Covid-19’, 2 February 2021. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-announces-50-million-to-support-students-impacted-by-covid-19 (last visited 15 March 2024). Many universities have now set up their own funding programmes in this regard. in line with the increasing diversification of student cohorts.52x Earwaker, above n. 12, at 39; MacLeod and Green, above n.8, at 643. This is also in line with universities’ widening participation; see, for example, Higher Education Funding Council for England, Annual Report and Accounts 2006-7, Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 14 June 2007, at 11f. Cf. Crowley-Cyr, above n. 5, at 138; Walsh, Larsen and & Parry, above n. 10, at 406. It is our view that student support provisions should shift from a two-pronged approach, based upon the fundamental pillars of academic support and pastoral care, towards a more holistic and individualistic form of student support provision, with academic colleagues playing a key departmental role in this context.

8.1 Implementation

The success of a holistic student support provision at a departmental level relies in part upon student perceptions as to the approachability of departmental colleagues.53x Cf. C. Baik, W. Larcombe & A. Brooker, ‘How Universities Can Enhance Student Mental Wellbeing: The Student Perspective’, 38 Higher Education Research and Development 4, at 680 (2019). In this regard, it is vital that students have the opportunity to strike up a rapport with both academic and professional services colleagues. The structured availability of academic advisors to facilitate either structured or ad hoc contact with their advisees through academic drop-in hours is a staple in most UK higher education institutions.54x Cf. The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, Contact Hours: A Guide for Students, August 2011, Gloucester, p. 2f. Available at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/quality-code/contact-hours-student.pdf?sfvrsn=5046f981_8 (last visited 15 March 2024); The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, Explaining Contact Hours: Guidance for Public Institutions Providing Public Information about Higher Education in the UK, August 2011, Gloucester, p. 4. Available at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/quality-code/contact-hours-guidance.pdf (last visited 15 March 2024). However, it is our view that for departmental student support to be both effective and inclusive, structured regular contact between academic colleagues and their students is necessary55x Cf. Baik, Larcombe & Brooker, above n. 53 advocating that student well-being would be improved if academic staff were more approachable. to give students the opportunity to have one-to-one dialogue with academic colleagues outside of the classroom context.

We recognise that there is a multitude of ways rapport can be achieved between academic colleagues and their students.56x McChlery and Wilke, above n. 8, at 28. Cf. C.M. Estepp and T.G. Roberts, ‘Teacher Immediacy and Professor/Student Rapport as Predictors of Motivation and Engagement’, 59 NACTA Journal 2, at 161 (2015) on ways in which the rapport building process can be aided. Indeed, the term ‘academic advisor’ itself would be better replaced by the term ‘personal tutor’ to encompass the broader focus and remit of the support provision. Moreover, the structured contact between academic colleagues and students that this forum entails humanises pastoral care signposting and enshrines its fundamental importance through structured colleague resource provision57x Cahill, Bowyer & Murray, above n. 47, at 410 providing for the importance of staff accessibility and availability, as well as the importance of dedicated staff time for student support provision, in this regard. rather than mere ad hoc enquiry. It also responds directly to the concerns raised in the context of the 2008 National Student Forum58x Cf. Department for Business Innovation and Skills (DBIS), 2008. National Student Forum: Annual Report (DBIS 2008). Available at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/14220/ (last visited 8 April 2024). and further exemplified by the COVID-19 pandemic by enshrining frequent student contact with academic colleagues as fundamental to effective student support provision.59x Cf. R. O’Connor, above n. 3, at 254. See also: R. Raaper, C. Brown & A. Llewellyn, ‘Student Support as Social Network: Exploring Non-traditional Student Experiences of Academic and Wellbeing Support During the Covid-19 Pandemic’, 74(3) Education Review, at 402 (2022); G.M. Collins, ‘Pastoral Support: Student Views’ in L. Bleasdale (ed.), How to Offer Effective Wellbeing Support to Law Students How To Guides (2024), 39-41. In particular, early on in a student’s academic studies, the importance of fostering the personal tutor relationship cannot be understated.60x Cf. P. Wilcox, S. Winn & M. Fyvie-Gauld, ‘“It Was Nothing to Do with the University, it Was Just the People”: The Role of Social Support in the First-year Experience of Higher Education’, 30 Studies in Higher Education, at 719 (2023).

In essence, the adoption of a holistic approach to student support entails a plea for empathy and compassion on the part of academic colleagues when faced with students experiencing pastoral care and, in particular, well-being concerns.61x Cf T.N. Baker, ‘How Top Law Schools Can Resuscitate an Inclusive Climate for Minority and Low-Income Law Students’, 9 Georgetown Journal of Law & Modern Critical Race Perspectives, at 126-7 (2017). Essentially students should feel heard, seen and cared for within their law school and by their law school community.

Of course, the adoption of a holistic approach to student support also requires that pastoral care, in particular well-being support, is appropriately entrenched by all higher education institutions as an integral component of the pedagogical development provision they offer.62x Cf. Laws and Fielder, above n. 33 from an Australian perspective. Cf. Earwaker above n. 12, at 132 in relation to student support. It furthermore requires institutional investment in training provision to ensure that academic colleagues possess sufficient knowledge of the relevant institutional support framework to facilitate effective signposting to sources of pastoral care provision.63x Cf. Earwaker above n. 12, at 99. This may include but is not limited to mental health training,64x Appleby and Burke, above n.31. as well as in-house training on specialised student support provision, for example, from the university’s counselling service and the students’ union. Moreover, and acknowledging the variations in departmental colleagues -to-student ratios across law schools both nationally65x Cf. The Guardian, ‘The Best UK Universities 2022 – Rankings Which Uses Student to Staff Ratio as a Performance Indicator’. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/ng-interactive/2021/sep/11/the-best-uk-universities-2022-rankings (last visited 22 March 2024). and internationally, individual allocations of personal tutees must be proximate to individual colleague workload allocations. This ensures that academic colleagues have sufficient time to dedicate to each individual tutee to enable holistic student support provision to take place and to appropriately foster the development of mutual trust and respect, which is necessary for the effective functioning of the personal tutor-to-tutee relationship.

In the context of legal education in England and Wales, the introduction of the Solicitors’ Qualifying Exam (SQE) in September 202166x For further information on the SQE see SRA, ‘Solicitors Qualifying Examination (SQE) route, Solicitors Regulation Authority’. Available at: https://www.sra.org.uk/become-solicitor/sqe/ (last visited 18 March 2024). continues to represent a unique opportunity for law schools in England and Wales to recalibrate and realign their undergraduate LLB programmes. In this context, student support provision can also be bolstered and rendered more holistic by way of greater integration into programme design.67x Cf. Crowley-Cyr, above n. 5, at 132 on the integration of information on well-being awareness into law programmes; Macduff and Holmes, above n. 29; Strevens and Wilson, above n. 29. Also see the ‘Enhancing Student Wellbeing’ project from the University of Melbourne: Enhancing Student Wellbeing, Resources for University Educators. Available at: http://unistudentwellbeing.edu.au/about-the-project/ (last visited 18 March 2024).8.2 Benefits

Tailored, individualistic student support ultimately has the potential to lend itself to greater efficiency in that students need only consult one member of departmental colleagues for both academic advice and signposting to sources of pastoral care.68x Cf. McChlery and Wilke, above n. 8, at 25. Such student support provision should have a developmental focus and, in doing so, foster a positive student experience by being inclusive.69x Cf. Earwaker, above n. 12, at 33. Indeed, regular contact with academic colleagues is frequently championed as being a key factor in creating a positive student experience,70x Ibid., at 126. Also see Universities UK, ‘Student Mental Wellbeing in Higher Education Good Practice Guide’ (2000), February 2015, p. 19. Available at: https://www.m25lib.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/student-mental-wellbeing-in-he.pdf (last visited 4 June 2024).whilst recognising the importance of the role of academic colleagues in supporting student well-being.71x Baik, Lareombe & Brooker, above n. 53, at 679; cf. O’Connor, above n. 3, at 254.

The established role of law lecturers as a natural point of contact within the department to source academic advice furthermore lends itself to conceptual expansion to enable colleagues to signpost students to alternative and, if applicable, more specialised forms of support.72x Cf. Quinn et al., above n. 49, at 414. It also recognises the fundamental importance of providing students with a listening ear73x Cf. Earwaker, above n. 12, at 78. whilst also simultaneously better reflecting the reality on the ground in that academic colleagues are already providing advice to students in relation to pastoral care.74x Cf. Walsh, Larsen & Parry, above n. 10, at 405. A holistic approach to student support equally relieves often overstretched departmental professional services colleagues of the sole responsibility for pastoral care and affirms the at-times-overlooked nurturing perspective of higher education75x Cf. D Pratt, ‘Good Teaching: One Size Fits All?’ 93 New Directions for Adults and Continuing Education, at 11 (2002). by emphasising that supporting student well-being is and also should be within the remit of the role of an academic.76x Baik, Lareombe & Brooker, above n. 53, at 679; N.L. Crawford and S. Johns, ‘An Academic’s Role? Supporting Student Wellbeing in Pre-university Enabling Programs’, 15 Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 3, at 6 (2018), from an Australian perspective; N. Duncan, C. Strevens & R. Field, ‘Resilience and student wellbeing in Higher Education: A Theoretical Basis for Establishing Law School Responsibilities for Helping our Students to Thrive’, 1 European Journal of Legal Education 1, at 86 (2020).

Student support furnished holistically moreover can shift from predominately reactive student support to targeted and proactive student support.77x Cf. Earwaker, above n. 12, at 132. Also see Cameron and Siameja, above n. 28; Ferris, above n. 4, at 7. This can function as an early warning system to identify and remediate the root causes of both academic and welfare issues before they arise or further escalate, in doing so promoting both student progression and greater student retention. Furthermore, a proactive approach to student support also lends itself to student empowerment.

The existence of a fixed departmental point of contact known to the student increases the transparency of student support services in general, which can act as a deterrent in students accessing appropriate support.78x Cf. Quinn et al., above n. 49, at 412. It furthermore serves to cultivate a ‘culture of openness’79x Ibid., 414. in which students on the one hand feel just as able to raise and ask for help with a well-being issue as they do for an academic issue and academic colleagues on the other hand feel equally confident in addressing both issues. Dispensing with the strict categorisation of student support queries also places academic support and pastoral care on a more even footing.8.3 Challenges

The challenges of this integrated approach include the risk of encouraging dependency80x Cf. Earwaker, above n. 12, at 65. and in turn discouraging student independence and autonomy, particularly given the importance placed upon fledging the personal tutor relationship. Nevertheless, the role of the personal tutor in signposting to institutional sources of pastoral care provision, rather than providing it directly, mitigates this risk to some extent.

A move towards more holistic student support provision also acknowledges the constraints of academic colleagues in respect to time, resources and expertise,81x Cf. Cahill, Bowyer & Murray, above n. 47, at 410; Duncan, Strevens & Field, above n. 76, at 114; Earwaker, above n. 12, at 49; Quinn et al., above n. 49, at 406. See Section 8.1 in relation to mitigating the effects of this challenge. whilst also emphasising the need for institutional investment in this regard. In this respect, it is worth emphasising that it is not the authors’ intention to create additional workload for academic colleagues; rather, it is about setting aside pre-existing time for the purpose of structured availability to be part-utilised differently towards a structured contact provision to foster positive student well-being. It is again important to reaffirm that academic colleagues should be signposting to, rather than providing, specialised pastoral care, for example, counselling, themselves. It is also important to note that it is not the authors’ intention to divert colleagues resources away from teaching and facilitating learning. Rather, it is mooted that student well-being needs can ill afford to be neglected by law schools and should be both considered and addressed by departments in order to render teaching and learning fully inclusive.8.4 Outlook

It is our view that the benefits of a holistic approach to departmental student support in law schools outweigh the challenges in providing a dedicated and comprehensive platform to support law students, which connects them to their teaching colleagues in such a way so as to facilitate proactive and ongoing integrated support provision. In doing so, increased efficiency may be won, but, perhaps more importantly, it is ultimately the aim for law students to feel wholly supported throughout their studies.

-

9 Conclusion

This article has reaffirmed the well-established link between student support on the one hand and progression, retention and a positive student experience on the other hand. It has furthermore asserted that the traditional distinction between the two pillars of student support – academic support on the one hand and pastoral care on the other hand – is, though theoretically valuable, no longer reflective of current practice in higher education settings and vitally no longer adequately caters for law students’ well-being. It is now appropriate to reconsider the design of student support, with the aim of making it more accessible and inclusive for students to help support their educational learning development.

To guide the systematic operationalisation of student support, this article has conceptualised a taxonomy to demonstrate the potential way student support systems can be structured to allow for more inclusive access points for students. In doing so, it has identified a key role for law schools’ academic colleagues in providing holistic student support, to include both academic support and signposting to appropriate pastoral care, as the key point of contact within an academic department. The challenge is being able to find the resources necessary to make student support more inclusive, whereas the complication is reviewing and re-evaluating existing structures that have evolved over time. At minimum, we have aimed to start a conversation to think about how we structure student support to make it more inclusive and holistic going forward.

Though academic colleagues may face challenges in sculpting student support in a holistic and inclusive manner, ultimately it is contended that to effectively accord departmental student support a human face, that face must be one known to and trusted by students.

Noten

-

1 G. Layer, ‘Developing Inclusivity’, 21 International Journal of Lifelong Learning 3, at 4 (2002).

-

2 Cf. S. Coyle, ‘“Make glorious mistakes!” Fostering Growth and Wellbeing in HE Transition’, 56(1) The Law Teacher 37, at 40 (2022); J. Duffy, R. Field, K. Pappalardo, A. Huggins & W. James, ‘The “I Belong in the LLB Program” Animating and Promoting Law Student Wellbeing’, 41 Alternative Law Journal 1, at 52 (2016); N. Duncan, R. Field & C. Strevens, ‘Ethical Imperatives for Legal Educators to Promote Law Student Wellbeing’, 23 Legal Ethics 1-2 at 65 f (2020); H.-W. Rückert, ‘Students’ Mental Health and Psychological Counselling in Europe’, 3 Mental Health and Prevention at 38-39 (2015).

-

3 A. Parfitt, S. Read & T. Bush, ‘Can Compassion Provide a Lifeline for Navigating Coronavirus (COVID-19) in Higher Education?’ 39 Pastoral Care in Education 3, at 187 (2021) providing that ‘the COVID-19 pandemic has apparently brought to the fore the vulnerabilities of all human bodies.’ Cf. J. Neves and R. Hewitt, ‘Student Academic Experience Survey 2021’, Advance HE, at 50. Available at: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/SAES_2021_FINAL.pdf (last visited 20 March 2024); R. O’Connor, ‘Supporting Students to Better Support Themselves through Reverse Mentoring: The Power of Positive Staff/Student Relationships and Authentic Conversations in the Law School’, 57 The Law Teacher 3, at 254 (2023).

-

4 Cf. Coyle, above n. 2; Duffy et al., above n. 2, at 52-53; Duncan et al., above n. 2, at 68; L.D. Eron and R.S. Redmount, ‘The Effect of Legal Education on Attitudes’, 9 Journal of Legal Education 4, at 435 (1957) identified law students as obtaining significantly higher anxiety scores in particular in comparison to medical students; G. Ferris, ‘Law-Students Wellbeing and Vulnerability’, 56 The Law Teacher 1, at 7 (2022); N. Kelk et al., ‘Courting the Blues: Attitudes towards Depression in Australian Law Students and Lawyers’, Brain and Mind Research Institute, University of Sydney, at 1 (2009); E.G. Lewis and J.M. Cardwell, ‘A Comparative Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing among UK Students on Professional Degree Programmes’, 43 Journal of Further and Higher Education 9, at 1229-1231 (2019); R.A. McKinney, ‘Depression and Anxiety in Law Students: Are We Part of the Problem and Can We Be Part of the Solution?’ 8 The Journal of the Legal Writing Institute, at 229 f (2002); K.M. Sheldon and L.S. Krieger, ‘Does Legal Education Have Undermining Effects on Law Students? Evaluating Changes in Motivation, Values and Well-Being’, 22 Behavioural Sciences and the Law, at 275 (2004); N. Skead and S.L. Rogers, ‘Stress, Anxiety and Depression in Law Students: How Student Behaviours Affect Student Wellbeing’, 40 Monash University Law Review 2, at 572 (2014); M. Townes-O’Brien, S. Tang & K. Hall, ‘Changing our Thinking: Empirical Research on Law Student Wellbeing, Thinking Styles and the Law Curriculum’, 21 Legal Education Review 2, at 150 and 159-60 (2011).

-

5 Cf. Duffy et al., above n. 2, at 52; Skead and Rogers, above n. 4, at 567. Other initiatives include the integration of information on well-being awareness into law programmes specifically: cf. L. Crowley-Cyr, ‘Promoting Mental Wellbeing of Law Students: Breaking-Down Stigma and Building —Bridges with Support Services in the Online Learning Environment’, 14 QUT Law Review 1, at 132 (2014).

-

6 The Guardian, ‘The Guardian University Guide 2024 – The Rankings’ (available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/universityguide (last visited 9 April 2024).

-

7 Cf. Neves and Hewitt, above n. 3.

-

8 For example, students identified as ‘at risk’: cf. S. McChlery and J. Wilke, ‘Pastoral Support to Undergraduates in Higher Education’, 8 International Journal of Management Education, at 24 (2009); For students with a disability, cf. A. MacLeod and S. Green, ‘Beyond the Books: Case Study of a Collaborative and Holistic Support Model for University Students with Asperger Syndrome’, 34 Studies in Higher Education, at 631 (2009).

-

9 D.M. Velliaris (ed.), Academic Language and Learning Support Services in Higher Education, Advances in Higher Education and Professional Development, at xiii (2019).

-

10 Cf. C. Walsh, C. Larsen & D. Parry, ‘Academic Tutors at the Frontline of Student Support in a Cohort of Students Succeeding in Higher Education’, 35 Educational Studies, at 411 (2009) listing the following student support services: academic tutor, student union, counselling, student finance, personal tutor, academic progression advisors, careers service, chaplaincy, student discipline service, student health service and so on.

-

11 M. Calvert, ‘From “Pastoral Care” to “Care”: Meanings and Practices’, 27 Pastoral Care in Education, at 269 (2009).

-

12 Cf. J. Earwaker, Helping and Supporting Students, Rethinking the Issues (1992), at 45.

-

13 J. Buckley, ‘The Case of Learning: Some Implications for School Organisation’ in R. Best, C. Jarvis & P. Ribbins (eds.), Perspectives on Pastoral Care (1980), at 183.

-

14 Ibid.

-

15 Ibid. See also: K. Knaplund and R. Sander, ‘The Art and Science of Academic Support’, 45 Journal of Education 157, at 160 (1995).

-

16 T.D. Peterson and E.W. Peterson, ‘Stemming the Tide of Law Student Depression: What Law Schools Need to Learn from the Science of Positive Psychology’, 9 Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law and Ethics, at 361 (2009).

-

17 Cf. A.G. Todd, ‘Academic Support Programs: Effective Support through a Systemic Approach’, 38 Gonzaga Law Review, at 187 (2002).

-

18 Cf. P.T. Wangerin, ‘Law School Academic Support Programs’, 40 Hastings Law Journal, at 773 (1989).

-

19 K.S. Knaplund and R.H. Sander, ‘The Art and Science of Academic Support’, 45 Journal of Legal Education 157, at 161 (1995). See also: S. Atkinson, Rethinking Personal Tutoring Systems: The Need to Build on a Foundation of Epistemological Beliefs (2014).

-

20 R. Best, C. Jarvis & P. Ribbins, ‘Pastoral Care: Concept and process’, 25 British Journal of Education Studies, at 125 (1977). See also: P. Ghengheshl, ‘Personal Tutoring from the Perspectives of Tutors and Tutees’, 42 Journal of Further and Higher Education, at 570 (2018).

-

21 P. Hughes, ‘Pastoral Care: The Historical Context’ in R. Best, C. Jarvis & P. Ribbins (eds.), Perspectives on Pastoral Care, at 28 (1980).

-

22 M. Maryland, Pastoral Care, at 11 (1974).

-

23 For example, A. Clemett and J. Pearce, The Evaluation of Pastoral Care, at 43 (1986). See also: C. Walker, ‘Wellbeing in Higher Education: A Student Perspective’, 40 Pastoral Care in Education 3, at 310 (2022).

-

24 S. Dooley, ‘The Relationship between the Concepts of Pastoral Care and Authority’, 7(3) Journal of Moral Education 182, p. 185 (1978).

-

25 Best, Jarvis & Ribbins, above n. 20, at 129.

-

26 Cf. Earwaker, above n. 12, at 45 providing that professional services staff may have a clearer picture as to the nature of support to provide than academic staff. Also see E. Hellwig, ‘Pastoral Care for the 1990s and beyond: A visitor viewpoint’, 7 Pastoral Care in Education, at 8 (1989) highlighting the problem with the lack of clarity on the nature of student support provided, the implementation of it, the development of any roles assigned with the provision of student support, and the type of support provided, which undermines policy decision-making in education.

-

27 Cf. Walker, above n. 23, at 317-18; Crowley-Cyr, above n. 5, at 132.

-

28 Cf. D. De Coninck, K. Matthijs & P. Luyten, ‘Subjective Well-being among First-Year University Students: A Two-wave Prospective Study in Flanders, Belgium’, 10 Student Success 1, at 42 (2019) recommending that student counsellors are made available within faculties. Also see Walker, above n. 23, at 313-14 on pastoral support teams inter alia existing within departments; see M.P. Cameron and S. Siameja, ‘An Experimental Evaluation of a Proactive Pastoral Care Initiative Within an Introductory University Course’, 49 Applied Economics 18, 1809 f (2017) advocating a ‘proactive pastoral care initiative’ in which academic staff provide tailored support to students identified at higher risk of non-completion.

-

29 Cf. Crowley-Cyr, above n. 5, at 132; A. Macduff and V. Holmes, ‘Harnessing the Winds of Change’, 56 The Law Teacher 1, at 133 (2022); C. Strevens and C. Wilson, ‘Law Student Wellbeing in the UK: A Call for Curriculum Intervention’, 11 Journal of Commonwealth Law and Higher Education 1, at 51 (2016).

-

30 Cf. T. Booth and M. Ainscow, Index for Inclusion: Developing Learning and Participation in Schools, Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education (2002), at 3. Also see Townes-O’Brien, Tang and Hallabove n. 4, at 176 providing for improved relationships with peers and teachers as creating a sense of community.

-

31 M. Appleby and J. Burke, ‘Promoting Law Student Mental Health Literacy and Wellbeing: A Case Study from the College of Law, Australia’, 20 International Journal of Clinical Legal Education 1, at 492 (2014) advocating MHFA training for all legal academics and those in student-facing roles.

-

32 Cf. Crowley-Cyr, above n. 5, at 133-35.

-

33 T.A. Laws and B.A. Fielder, ‘Universities’ Expectations of Pastoral Care: Trends, Stressors, Resource Gaps and Support Needs for Teaching Staff’, 32 Nurse Education Today, at 799 (2012).

-

34 Cf. Pastoral care definition in Section 5.2.

-

35 C. Smith and J. Allen, ‘Essential Functions of Academic Advising: What Students Want and Get’, 26 NACADA Journal 56, at 60 (2006).

-

36 Cf. Earwaker, above n. 12, at 132.

-

37 K. Galloway and R. Bradshaw, ‘Responding to Changed Parameters of the Law Student: A Reflection on Pastoral Care in the Law School’, 3 Journal of the Australasian Law Teachers Association 101, at 108 (2010).

-

38 Ibid., at 107-10.

-

39 This inherently relates to the current structures and policies implemented in law schools and higher education institutions in recent years. See on this, S. Brown, ‘Bringing about Positive Change in the Higher Education Student Experience: A Case Study’, 19 Quality Assurance in Education, at 195 (2011); D. Morrison and J. Guth, ‘Rethinking the Neoliberal University: Embracing Vulnerability in English Law Schools?’ 55 The Law Teacher, at 42 (2021).

-

40 G. Biesta, ‘What Is Education for? On Good Education, Teacher Judgement, and Educational Professionalism’, 50 European Journal of Education 75, at 75 (2005).

-

41 Ibid.

-

42 Ibid.

-

43 Earwaker, above n. 12, at 132.

-

44 Cf. Skead and Rogers, above n. 4, at 585 recognising the link between student well-being and a student’s sense of belonging.

-

45 Cf. De Coninck, Matthijs & Luyten, above n. 28; Walker, above n. 23, at 313-14.

-

46 Cf. De Coninck, Matthijs & Luyten, above n. 28.

-

47 See, for example, J. Cahill, J. Bowyer & S. Murray, ‘An Exploration of Undergraduate Students’ Views on the Effectiveness of Academic and Pastoral Support’, 56 Educational Research, at 406-7 (2014); D. Fitzsimmons, S. Kozlina & P.E. Vines, ‘Optimising the First Year Experience in Law: The Law Peer Tutor Program at the University of New South Wales’, UNSW Law Research Paper No. 2007-7 (2007); cf. Wangerin, above n. 18, at 783.

-

48 Cf. Townes-O’Brien, Tang & Hall, above n. 4, at 174. Also see Australian Law Students’ Association, Depression in Australian Law Schools: A Handbook for Law Students and Law Student Societies, 18-20. Available at: https://law.uq.edu.au/files/32504/alsa-depression-handbook.pdf (last visited 19 March 2024).

-

49 See: https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/graduate-college/information-for-students/the-buddy-programme/ (last visited 9 April 2024). This is also replicated at other universities, cf: N. Quinn, A. Wilson, G. MacIntyre & T. Tinklin, ‘People Look at You Differently’: Students’ Experience of Mental Health Support within Higher Education’, 37 British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, at 414 (2009).

-

50 Cf. Cameron and Siameja, above n. 28; Ferris, above n. 4, at 17.

-

51 Neves and Hewitt, above n. 3; O’Connor, above n. 3, at 253-4. This also includes financial support needs: cf. Gov.UK Press Release, ‘Government Announces £50 Million to Support Students Impacted by Covid-19’, 2 February 2021. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-announces-50-million-to-support-students-impacted-by-covid-19 (last visited 15 March 2024). Many universities have now set up their own funding programmes in this regard.

-

52 Earwaker, above n. 12, at 39; MacLeod and Green, above n.8, at 643. This is also in line with universities’ widening participation; see, for example, Higher Education Funding Council for England, Annual Report and Accounts 2006-7, Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 14 June 2007, at 11f. Cf. Crowley-Cyr, above n. 5, at 138; Walsh, Larsen and & Parry, above n. 10, at 406.

-

53 Cf. C. Baik, W. Larcombe & A. Brooker, ‘How Universities Can Enhance Student Mental Wellbeing: The Student Perspective’, 38 Higher Education Research and Development 4, at 680 (2019).

-

54 Cf. The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, Contact Hours: A Guide for Students, August 2011, Gloucester, p. 2f. Available at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/quality-code/contact-hours-student.pdf?sfvrsn=5046f981_8 (last visited 15 March 2024); The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, Explaining Contact Hours: Guidance for Public Institutions Providing Public Information about Higher Education in the UK, August 2011, Gloucester, p. 4. Available at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/quality-code/contact-hours-guidance.pdf (last visited 15 March 2024).

-

55 Cf. Baik, Larcombe & Brooker, above n. 53 advocating that student well-being would be improved if academic staff were more approachable.

-

56 McChlery and Wilke, above n. 8, at 28. Cf. C.M. Estepp and T.G. Roberts, ‘Teacher Immediacy and Professor/Student Rapport as Predictors of Motivation and Engagement’, 59 NACTA Journal 2, at 161 (2015) on ways in which the rapport building process can be aided.

-

57 Cahill, Bowyer & Murray, above n. 47, at 410 providing for the importance of staff accessibility and availability, as well as the importance of dedicated staff time for student support provision, in this regard.

-

58 Cf. Department for Business Innovation and Skills (DBIS), 2008. National Student Forum: Annual Report (DBIS 2008). Available at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/14220/ (last visited 8 April 2024).

-

59 Cf. R. O’Connor, above n. 3, at 254. See also: R. Raaper, C. Brown & A. Llewellyn, ‘Student Support as Social Network: Exploring Non-traditional Student Experiences of Academic and Wellbeing Support During the Covid-19 Pandemic’, 74(3) Education Review, at 402 (2022); G.M. Collins, ‘Pastoral Support: Student Views’ in L. Bleasdale (ed.), How to Offer Effective Wellbeing Support to Law Students How To Guides (2024), 39-41.

-

60 Cf. P. Wilcox, S. Winn & M. Fyvie-Gauld, ‘“It Was Nothing to Do with the University, it Was Just the People”: The Role of Social Support in the First-year Experience of Higher Education’, 30 Studies in Higher Education, at 719 (2023).

-

61 Cf T.N. Baker, ‘How Top Law Schools Can Resuscitate an Inclusive Climate for Minority and Low-Income Law Students’, 9 Georgetown Journal of Law & Modern Critical Race Perspectives, at 126-7 (2017).

-

62 Cf. Laws and Fielder, above n. 33 from an Australian perspective. Cf. Earwaker above n. 12, at 132 in relation to student support.

-

63 Cf. Earwaker above n. 12, at 99.

-

64 Appleby and Burke, above n.31.

-

65 Cf. The Guardian, ‘The Best UK Universities 2022 – Rankings Which Uses Student to Staff Ratio as a Performance Indicator’. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/ng-interactive/2021/sep/11/the-best-uk-universities-2022-rankings (last visited 22 March 2024).

-

66 For further information on the SQE see SRA, ‘Solicitors Qualifying Examination (SQE) route, Solicitors Regulation Authority’. Available at: https://www.sra.org.uk/become-solicitor/sqe/ (last visited 18 March 2024).

-

67 Cf. Crowley-Cyr, above n. 5, at 132 on the integration of information on well-being awareness into law programmes; Macduff and Holmes, above n. 29; Strevens and Wilson, above n. 29. Also see the ‘Enhancing Student Wellbeing’ project from the University of Melbourne: Enhancing Student Wellbeing, Resources for University Educators. Available at: http://unistudentwellbeing.edu.au/about-the-project/ (last visited 18 March 2024).

-

68 Cf. McChlery and Wilke, above n. 8, at 25.

-

69 Cf. Earwaker, above n. 12, at 33.

-

70 Ibid., at 126. Also see Universities UK, ‘Student Mental Wellbeing in Higher Education Good Practice Guide’ (2000), February 2015, p. 19. Available at: https://www.m25lib.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/student-mental-wellbeing-in-he.pdf (last visited 4 June 2024).

-

71 Baik, Lareombe & Brooker, above n. 53, at 679; cf. O’Connor, above n. 3, at 254.

-

72 Cf. Quinn et al., above n. 49, at 414.

-

73 Cf. Earwaker, above n. 12, at 78.

-

74 Cf. Walsh, Larsen & Parry, above n. 10, at 405.

-

75 Cf. D Pratt, ‘Good Teaching: One Size Fits All?’ 93 New Directions for Adults and Continuing Education, at 11 (2002).

-

76 Baik, Lareombe & Brooker, above n. 53, at 679; N.L. Crawford and S. Johns, ‘An Academic’s Role? Supporting Student Wellbeing in Pre-university Enabling Programs’, 15 Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 3, at 6 (2018), from an Australian perspective; N. Duncan, C. Strevens & R. Field, ‘Resilience and student wellbeing in Higher Education: A Theoretical Basis for Establishing Law School Responsibilities for Helping our Students to Thrive’, 1 European Journal of Legal Education 1, at 86 (2020).

-

77 Cf. Earwaker, above n. 12, at 132. Also see Cameron and Siameja, above n. 28; Ferris, above n. 4, at 7.

-

78 Cf. Quinn et al., above n. 49, at 412.

-

79 Ibid., 414.

-

80 Cf. Earwaker, above n. 12, at 65.

-

81 Cf. Cahill, Bowyer & Murray, above n. 47, at 410; Duncan, Strevens & Field, above n. 76, at 114; Earwaker, above n. 12, at 49; Quinn et al., above n. 49, at 406. See Section 8.1 in relation to mitigating the effects of this challenge.